Hindu Kush — Two Men and Nineteen Camps

The Tactics of a Mini Expedition

Mountaineering expeditions these days almost always have a definite summit in mind. Accordingly, all their planning is directed towards climbing it. If the peak happens to be in the Himalaya, the Karakorum or the Hindu Kush, then they are restricted to the terms of a permit, which must be obtained in advance from the government concerned – Nepal, Pakistan, China. They are obliged to keep to certain areas and named peaks. The small but extended Hindu Kush enterprise which Dietmar Proske and I undertook in 1967 was an altogether different proposition. In the first place, there were just two of us and we were not, officially, an expedition, but simply travelling as ‘sporting tourists’. Secondly, in spirit, this was a wide-ranging foray involving climbing and reconnaissance. For Dietmar, it was his first experience of the mountains of High Asia; I had been three times already and, besides, knew the Hindu Kush from an earlier, similar journey to the mountains of Chitral. However, since my first visit to the Tirich area, things were beginning to change and to be without a permit now could land you in big trouble. This was the end of the era when you could climb wonderful peaks and explore unknown valleys without asking anyone.

In some ways, I consider this mini-enterprise to have been my most successful expedition. Hermann Buhl’s alpine-style thinking, with which I became familiar on Broad Peak and Chogolisa in 1957, had left its influence on me. The concept, I believed, could be expanded to apply to a whole mountain area.

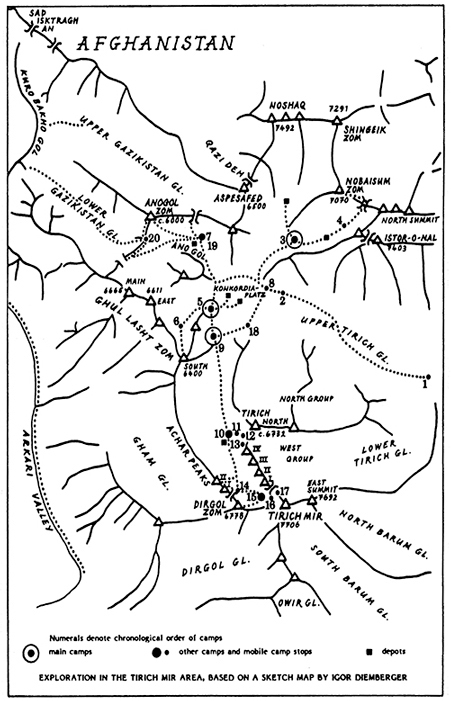

I do not intend a full narrative of events, but want to demonstrate, by means of a compressed expedition diary and a sketch map, the complete comings and goings of our trip, with its repeated setting-up of camps (and depots) for our various objectives. On top of that I will endeavour to give the thinking behind the preparations we made for all this activity to show how a small two-man expedition with multiple aims can work and, depending on circumstances, could be repeated. Of course, there were times when Dietmar and I had to make the best of our situation, and times when luck played no small part in the outcome – but then, on any trip, you will always need some luck.

Looking north from Chitral – the main settlement in the area of that name in north-west Pakistan – you see the shining snows of Tirich Mir, high above the valleys. This mountain massif is the highest in the Hindu Kush, a range that includes several 7,000 metre peaks. Tirich Mir itself is 7,706 metres. Like a bastion, the massif thrusts south from the main spine of the Hindu Kush which forms the boundary between the Wakhan in Afghanistan and Chitral in Pakistan. On closer inspection the bulk resolves into crests, groups and single peaks, embracing mighty glaciers. Glacial tongues push out even into the barren brown mountain valleys to its east, south and west.

The second highest peak of the Hindu Kush, Noshaq (7,492 metres), and also the precipitous Istor-o-Nal (7,403 metres) are both linked to this system of crests, which encircles the multi-branched Upper Tirich glacier like a framework. This glacier is essentially the heart of the area.

It is not surprising that the seven-thousanders of the Hindu Kush and other fine peaks of lesser height in the area captured the interest of climbers, albeit relatively late. Not until 1960 was it possible to launch attempts on the main range from the Wakhan Corridor – that narrow strip of land bordering the Oxus River, and created as a sort of cordon sanitaire, a buffer zone between two areas of political interest, two empires, the Russian and the British-Indian. Well before this, however, British officers, maintaining the Gilgit Frontier, and surveyors explored the mountain world of the Hindu Kush from Chitral, which then came under British influence. And as early as 1929 and 1935 there had been attempts on Istor-o-Nal by British officers, although it was 1955 before an American team reached what it thought was the summit.[1] On Tirich Mir itself an attempt from the Owir glacier in 1939 led by Miles Smeeton was accompanied by the twenty-five-year-old Tenzing Norgay, but the first ascent was achieved only in 1950 when a Norwegian expedition led by Arne Naess approached from the south.

When, in 1965, with Herwig Handler, Franz Lindner and my wife Tona, I pushed beyond Istor-o-Nal to the heart of the mountains of the Upper Tirich glacier, we were pioneers from an alpinistic point of view. Only Reginald Schomberg before us had made a geographical exploration of the area in the 1930s.

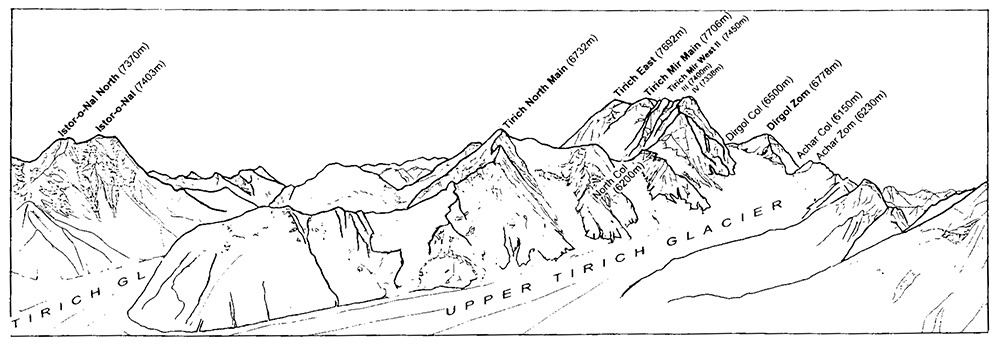

We found ourselves entering a wide glacier floor within what could best be described as a circle of mountains, beginning with the Tirich North group to our left. From where we were standing, the long southerly arm of the Upper Tirich glacier continued up towards the pre-eminent Tirich Mir, bypassing the granite castles of the Tirich West group. Rising beyond this glacier arm, to the west, were the white peaks of the Ghul Lasht Zom group, almost in front of us. To our right, Istor-o-Nal, with its steep flanks and flying buttresses, bounded the outgoing (eastern) stream of the glacier, which finally dispatched its meltwaters through the broad U-shaped valley of the Tirich Gol into the main river of Chitral. (This river changes its name from stretch to stretch: here it is the Mastuj.) A further arm of this intricately branched glacier system extended up between Istor-o-Nal and its close neighbour, Nobaisum Zom; another, in a wide sweep, flowed from the foot of the southern flanks of Noshaq and Shingeik Zom. The Anogol glacier (yet another branch) derived from the watershed between the Tirich basin and the two Gazikistan glaciers to its west. I wondered if, in the old days, people used to cross a pass here, down into the Arkari valley?

We christened the confluence of all these sidestreams of the Tirich glacier with a name borrowed from a similar, but more famous landmark on the Baltoro in the Karakorum, Concordia or, as we preferred it, Konkordiaplatz. Our 1965 expedition was crowned not only with the first ascent of the 6,732-metre Tirich North, but of three further six-thousanders in the nearby Ghul Lasht Zom group. We also gained some remarkable scientific results: Tona, a geologist, did the preliminary research for the first geological map of the area. We discovered enormous intrusions of granite in the dark slates (which turned out to be Paleozoic); they had forced crystalline dykes into the sedimentary rocks which had once been an ancient ocean bed (we found fossils in some places). Beautiful minerals formed from this conjunction of rocks lay everywhere around: black-rayed ‘suns’ of tourmaline and rose-coloured flakes of mica, shimmering like silk. My heart, like Tona’s, quickened at such fantastic finds – after all, had not my own path to the mountains begun as a young rock-hound so many moons ago? Alpinistic objectives apart, we could see there were geological enigmas in plenty awaiting resolution: clearly, a return visit was called for. Two years later I managed to come back.

But this time everything was different. Whereas before we had been the only people on the Upper Tirich glacier, now, in 1967, the Tirich area was attracting the attention of many mountaineers. Two strong expeditions penetrated the southern branch of the Upper Tirich glacier, one behind the other: Czechoslovaks, under Vladimir Sedivy, and Japanese, with K. Takahashi as leader. Both intended an attempt on Tirich Mir from the west (this would be a new route: the Norwegian first ascent in 1950 had been via the south ridge).

Also busy in the massif was an Austrian group from Carinthia, led by Hans Thomaser. They wanted to open a steep route on Tirich Mir from the south-west, from the Dirgol valley. The leader and his companion died during the summit attempt, and it was not until 1971 that a Japanese team succeeded from this direction.

A three-man party from Salzburg exploring on the Upper Tirich glacier, our area, included my friend Kurt Lapuch. This group climbed the north peak of Istor-o-Nal; and Kurt and I stood together on the first seven-thousander of my Austrian Hindu Kush Reconnaissance, 1967. Technically, I was a one-man expedition – as lightweight as you could get – but I should quickly add that another solo party, the German Hindu Kush Reconnaissance, 1967 – namely, Dietmar Proske – was active at the same time. The two of us had made separate plans to come here, although we agreed to travel together. Not knowing each other beforehand, it seemed prudent to remain basically independent, leaving each of us free to team up with other parties or make solo ascents. In the event, apart from a couple of days, Didi and I were always together and the collaboration worked so happily that you might just as well consider us a two-man expedition.

And our goals?

One strong reason for my coming back was because the west peaks of Tirich Mir, still untouched by man, beckoned along the southern branch of the glacier. Beautiful, wild seven-thousanders! There in 1965 we had cast the first exploring glances into the far reaches of the Tirich glacier – and, not least, at the west face of Tirich Mir. In consequence, Didi and I hoped gradually to penetrate this east-curving glacier arm, and climb several of the surrounding peaks in the process: in particular we set our sights on the beautiful pyramid of Dirgol Zom (6,778 metres) and one or two of the Achar Peaks – a silhouetted crescent of six-thousanders which separated the western rim of the Upper Tirich glacier from the deeply cut furrow of the Arkari valley, 3,000 metres below. It goes without saying that we also hoped for the chance to climb Tirich Mir itself – either by a route being pioneered by the big expeditions or, better still, a new one of our own. To our dismay, as I said, bureaucratic difficulties had arisen since 1965: the Pakistani government now demanded an official expedition permit for Tirich Mir. We wondered if, perhaps, it would be possible to ride on the coat tails of the Czechs or Japanese. We had no wish to upset the government, but my oh my! Tirich Mir was a most beautiful mountain ...

What about the other peaks? No problems, there: as ‘sporting tourists’ the authorities in Peshawar had granted us a fine permit, rubber-stamped to allow us to fish, roam freely so long as our wanderlust held out – including in snow and glacier areas (be it noted!), and to explore possible ski areas (they said this would be good for tourism). I took it that we could also climb all those peaks which were not on the special list prepared by the Ministry of Tourism as requiring the standard expedition permit. But what peaks these were was for us then a matter of conjecture, and we were wary of asking too many questions. Unfortunately, everyone knew that Tirich Mir was an official mountain ...

This, then, was the transitional period, with many things left open to individual interpretation. Were we an illicit enterprise? No, no, God forbid! Even so, there was the risk of surprises: my friend Gerald Gruber, a geographer from Graz and a dedicated Hindu Kush hand, found himself one fine morning in a village where the local police would not allow his porters to go on. He had to call off his exploration. That is why Didi and I treated the liaison officers of the big official expeditions with the utmost respect. Twelve years later, in 1979, linked by friendship and a rope to our liaison officer Major Fayazz Hussain, I would break trail for many hours with him through the deep snow of an eight-thousander to share the joy of a summit success on Gasherbrum II. But in 1967, Didi and I could not bank on such harmony, nor hope that our happy-go-lucky wide-ranging (and, we hoped, high-reaching) sporting activities would be seen as a reasonable interpretation of our special permit. Hence, we hesitated before accepting the invitation ‘Please come for tea’ from a liaison officer down at the bottom of the Tirich Gol valley. That is to say, we accepted, yes, from the safety of our inaccessible glacier world, but then had to postpone the date, over and again, because of ‘sickness’. We strung it out until we had ‘hooked’ all our ‘fish’ ... In the end I did ‘come for tea’, but from the other direction, up-valley, having fulfilled my wish to encompass the whole Tirich Mir massif.

Nudging Alpine-Style a Step Further

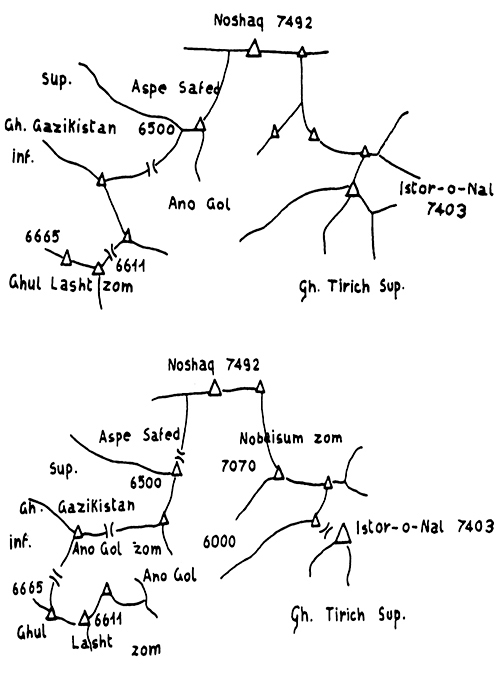

Back to our plans! I wanted our climbs and exploration to include the opportunity to collect more rock samples for widening the geological map; I developed a special interest in the Ghul Lasht Zom group, because the old kammkarte of the area to the north of there, towards the Anogol glacier, was definitely wrong. Also, the southern peak of that group, a six-thousander, was still virgin – the only one we had failed to bag in 1965. And incidentally, what was on the other side of the Anogol – could you climb down there?

So far, nobody had ever succeeded on the south face of Noshaq. Nearby soared the virgin and nameless P6999 and you could elevate that to a seven-thousander with your own body. Aims upon aims, possibilities without end ...

Ever since I was on the Baltoro glacier with Hermann Buhl, I have been committed to alpine-style, even when, as on Dhaulagiri in 1960, I could not put it into practice. (The oxygen at least remained unused on that trip.) What handicapped us in achieving multiple alpine-style successes in 1957 were the many miles of moraine rubble and glaciers over which all the necessary gear and food for other mountains would have needed to be carried. But given the acceptance of a multitude of targets from the beginning of an expedition – and accepting, too, the premise that in the Himalaya all alpine-style mountaineers employ porters to help get gear and food to their base camp below the mountain – then it is clear what should be done: create an appropriate depot system at the outset.

As I said, in 1967 we had no shortage of aims or possibilities capable of being realised by just two climbers in alpine-style. The term nowadays is usually only applied to the ascent of a mountain; for us, it included exploration and discovery as well. To explore more than one massif, and include successful quality climbing, you have to push the style even further. You need a network of depots for your intended camps, that still allows you the option of adjustment where necessary. The better you plan this beforehand, the less will land on your back later!

For our multiple targets, we required elastic planning. We only had a very limited number of tents: a couple of bigger ones for normal camps and a lightweight tent for moving around at high level on steep mountainsides – a Desmaison design with two vertical tent poles. This latter gave us extreme mobility. We could proceed for days, setting it up night after night at a higher – or at least different – place, saving ourselves from dangerous bivouacs. Hermann Buhl and I had already employed such a ‘wandering high camp’ in 1957 on Chogolisa, his last climb: it represented the lightweight extreme of our west alpine-style (no high-altitude porters or oxygen gear for the climb), and corresponded to the purest alpine-style, even by today’s definition. This dynamic climbing technique – often embellished with the term ‘bivouac’, although the use of the tent demonstrates it cannot be that – proves wonderfully effective as well for traverses of every kind, and for far-reaching exploration. We used our lightweight tent in making the grand circuit of Tirich Mir, and it was equally useful during the climb of the mountain itself, as well as on Tirich West IV, another seven-thousander, and the aforementioned P6999. It would in any case have been utterly impossible for us to set up a chain of camps, in the way that big expeditions do. In a sense, we got close to the ‘capsule-style’ concept advocated by Chris Bonington, the British master of strategy.

Our self-sufficient little team made frequent use of depots. We cached a duffel bag or an aluminium box with food and equipment on the Anogol glacier; on the southern branch of the Upper Tirich glacier; two such caches on the Konkordiaplatz; another on the north face of Tirich West IV; and yet another below Noshaq; as well as several more. The addition of a tent to any of these depots meant instant transformation into a camp. Conversely, if a tent was needed elsewhere, returning a camp to a cache was equally simple. Even a reader inexperienced in mountain craft will see how flexible an expedition can be with the aid of such relay-stations. It is incredible how much distance can be covered when the layout of these stations follows a logical pattern.

In the course of our two months’ stay in the Tirich area we only employed a single porter, Musheraf Din and, even then, sent him back to his village for a holiday every so often! It did mean a lot of carrying ourselves. There had been twelve porters on the march in; they deposited our gear in more than one place and the subsequent redistribution we did ourselves. Obviously, the honesty of the porters is an integral requirement of this system, but that was guaranteed for us by Musheraf Din and his people. No less important was the fact that the porters of every other expedition came from the same village – Shagrom Tirich – and Musheraf Din was their mayor!

But now: how to proceed? More precisely: how to extend the lightweight strategy for a chosen climb? In the centre of your field of action – for example where the southern branch of the Tirich glacier flows into the Konkordiaplatz – you convert a depot into a main camp. (Alternatively, the necessary gear can be brought from the nearest cache, or from the last point of action. There’s no danger that things might become too easy – you’ll always find some load or other that needs ferrying! Logistics can never be that fail-safe, especially when you have a limited amount of equipment. Once, we were faced with gathering what we needed from three different spots.)

After setting up the new main camp, you add a small ‘high base’ at the foot of your desired peak, a miniaturised ABC (the advance base camp of a large expedition). From there, you either start the climb in purest alpine-style, carrying just your lightweight tent, the ‘ladder’ of camps being reduced to a single mobile rung. Or, what is usually advisable, make a higher cache first, in order to reconnoitre before the final assault; and if circumstances or safety require it, to set up a high tent beforehand and start the ‘mobile rung’ climb from there. Common sense has to outweigh doctrine in the mountains – if you want to live to tell the tale. Whether and where to put a cache should depend on the situation. Tirich West IV (7,338 metres), this beautiful granite castle, was explored and climbed by us in this manner, taking seven days from the bottom. We chose a giant ice ramp and the north buttress for this first ascent.

During our seven weeks on the Upper Tirich glacier we employed the following ‘base camps’ in turn: one at the foot of Istor-o-Nal (facing Noshaq and Nobaisum Zom); the next to the east of the Ghul Lasht Zom peaks; a third at the start of the southern branch of the Tirich glacier; and finally a sort of permanent satellite in the remote AnoGol basin. Altogether we established nineteen camps, and once occupied the abandoned tent of another party.

This elasticity worked well: we succeeded on three seven-thousanders – including Tirich Mir itself (7,706 metres). The other two of them were first ascents: Tirich West IV and Nobaisum Zom (the freshly-christened P6999, which we found to be 7,070 metres.) And to these, we added four six-thousanders. It cost us a lot of sweat and on-the-spot reckoning.

As a tiny team to have ‘conquered’ – or rather, made ours – the mountains of a whole area and, ultimately, to have circled the main massif; to have succeeded on a row of beautiful peaks on the Upper Tirich glacier, with remarkable distances to cover; and to overcome all the logistical barriers in the course of this mini-enterprise – that was an adventure which, today, fills me with more satisfaction than if Dietmar and I had climbed an eight-thousander somewhere else. Several hundred more metres of altitude are fine, but taking everything into consideration, that would have been less interesting, less original – and much simpler! Reinhold Messner’s Challenge, which he and Peter Habeler undertook on Hidden Peak (8,068 metres) some years later, produced a great climb that was widely acclaimed as innovative. But the principle had been enacted earlier – more than once, on 7,000-metre peaks, and Reinhold’s ‘bivouacs’ were practically camps – the highest offered a double-fabric silk and perlon tent and sleeping-bags. Reflecting on the summer Dietmar Proske and I spent in the Hindu Kush, the difference, it seems to me, was merely a few pitches of rope, given the fact that Hidden Peak only just exceeds the magic 8,000-metre line and its logistical difficulties were nothing by comparison. Reinhold, for his part, drew a not so apt comparison between his climb and the first ascent of Broad Peak in 1957. His 1975 expedition, he said, required only a tenth of the total weight in equipment and food that ours had done. Moreover, he had not taken a doctor. I could not resist a smile at that remark, at least. But for the mathematics, we had been four climbers, not two; we had been utterly alone on the Baltoro glacier; and moreover, it had been almost two decades earlier. How many changes had taken place in that time, in equipment alone! On top of that, Reinhold used twelve porters to get to his starting point – just as we did in 1967 in the Hindu Kush. Of course Hermann Buhl’s west alpine-style on Broad Peak was heavier and less elegant than Reinhold and Peter’s method of climbing Hidden Peak, but the revolutionary concept was his and crystallised soon afterwards in the purest alpine-style employed on Chogolisa and Skil Brum. On Hidden Peak, an old style and an old concept had been applied – without question in a brilliant way!

After this ‘spiritual excursion’ to the Baltoro, let us return to the relative quiet of the Hindu Kush. Three eventful months – a great time!

Sketch panorama of the Tirich Mir area from the Ghul Lasht Zom (NNW) by Josep Paytubi, from photographs by Kurt Diemberger Noshaq 7492.

An Expedition Journal

Dietmar and I met in early June to assemble the equipment. After three days the total weight of 500 kilos had been reduced to 420 kilos and strong rear-wheel shock absorbers fitted to the car. We drove for two weeks across Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan. At Dir, in Pakistan, we ‘garaged’ the car in what we hoped was a burglar-proof way by driving it on to someone’s veranda up a ramp of planks knocked together by local men and then removed. We proceeded by Jeep for two days, hired donkeys for two more, then set off on foot with twelve porters to Shagrom and the Tirich valley.

Our objective was the Rhubarb Patch, known locally as Chur Baisum, where the Lower Tirich glacier enters the valley of the Upper Tirich glacier. The Lower Tirich is small and narrow, squeezed in between the north face of Tirich Mir and the Tirich north group. This Rhubarb spot could be a good base for a first ascent of Tirich Mir’s north face!

Sketch panorama of the Tirich Mir area from the Ghul Lasht Zom (NNW) by Josep Paytubi, from photographs by Kurt Diemberger.

The diary continues:

5 July Didi and Kurt pitch their tents some distance before the base camp already established by the Czechs.

6 July While Kurt is chatting in the Czech mess tent with them and their liaison officer, Didi, who has made an early start, passes with our porters. We march along the south flank of Istor-o-Nal to a spot shortly beyond called Nal, or Horseshoe. Years ago, according to the locals, one used to be able to take horses through from here to Afghanistan. Today the glaciers don’t allow that.

7 July Didi and Kurt head on, turning right at the western edge of Istor-o-Nal to the northern arm of the Upper Tirich glacier. This is where Kurt Lapuch’s Salzburgers had their base camp for climbing the north summit of Istor-o-Nal; they have now marched off to Shagrom. We set up our tents, and Lapuch arrives, following an invitation from Kurt. Nobaisum Zom (P6999) will be tackled from here by the two of them. After establishing a depot at Konkordiaplatz all porters except Musheraf Din are sent home. This depot will supply further depots to the south and west.

8 July Starting from Nobaisum Base Camp a high cache is established at 5,800 metres.

9 July Lapuch and Kurt depart from Base Camp for their summit attempt and set up the lightweight tent at 6,050 metres. The route for Nobaisum Zom will take the gap between this mountain and Istor-o-Nal, then follow the ridge to the summit. Didi makes a reconnaissance towards Noshaq – another possible objective of our enterprise – and sets up a depot.

10 July First ascent of Nobaisum Zom (7,070 metres by aneroid).[2]

11 July Descent to Nobaisum Base Camp.

12 July Lapuch marches off. A little later a gigantic rockfall roars down the granite wall of Istor-o-Nal near Base Camp. Musheraf Din fetches the rucksack with our food, which had been deposited for the ascent of Noshaq. The reconnaissance has revealed the approach to the face to be too complicated and dangerous; Noshaq will not be climbed this time.

13 July Now the push into the Ghul Lasht Zom group must be prepared. Kurt will stay a short while at the Nobaisum Base because of phlebitis in one leg which has become worryingly thick. Didi and Musheraf Din are bringing material from the depot at Konkordiaplatz to the foot of the Ghul Lasht Zom peaks. Establish Ghul Lasht Zom Base Camp (4,950 metres).

14 July Same procedure. Musheraf Din afterwards goes off for a ‘holiday’ to Shagrom. Kurt’s leg luckily is getting better after treatment with several medicines. No ill effects. Later he admits rushing up a 7,000-metre peak immediately on arrival is a dangerous error.

15 July Didi climbs Panorama Peak (about 5,600 metres, first ascended in 1965). Kurt arrives from Nobaisum Base Camp.

16 July Kurt and Didi, on ski and skins, ascend the south branch of the Upper Tirich glacier, to a height of 5,500 metres, then ski down it for several kilometres. The run is very difficult and not worth it on account of a long stretch of small penitentes. In 1965 there had been good snow conditions on the southern branch, but we had no skis then.

17 July Departure for exploring the Ano Gol, the north-west branch of the Upper Tirich glacier. The access to Ano Gol is barred by an enormous icefall, which can be bypassed on the left (southern) side over a steep rock section. The penitentes make very heavy going. Climbing up to the saddle between Ano Gol and the Upper Gazikistan glacier, the latter belonging to the Arkari valley side of the watershed. From the saddle (c. 5,500 metres) a knoll (5,600 metres) is ascended. This gives a very illuminating view: a descent from Ano Gol to the Upper Gazikistan glacier could be possible, but very difficult. According to Schomberg, there might once have been a passage here for shepherds or smugglers down to the Arkari valley, and on into Afghanistan. Maybe ice conditions were better then. Another revelation is that between the Ano Gol and the glacier at the northern foot of the Ghul Lasht Zom group, there appears to be no barrier. Its ice flows for the most part down to the Ano Gol glacier, and consequently into the Upper Tirich. Only a small amount finds its way into the Lower Gazikistan glacier. The old kammkarte is wrong here. Interesting finds are blocks crammed with paleozoic crinoids on the left-hand-side moraine of the Ano Gol glacier, originating from the southern precipices of the Asp-e-Safed group. Return to Ghul Lasht Zom Base Camp the same day.

18 July Day off. Didi gets some provisions from Konkordiaplatz.

19 July Start for the Ghul Lasht Zom group. Set up a High Camp (5,700 metres) in a glacial basin which is surrounded by Panorama Peak, Ghul Lasht Zom South, Dertona Peak and Ghul Lasht Zom East.

20 July First ascent of Ghul Lasht Zom South (6,400 metres) by Didi and Kurt from the High Camp. Great view of Tirich Mir and all the peaks around the Upper Tirich glacier.

Sketch map of the Upper Tirich Glacier area before (above) and after (below) our 1967 expedition.

21 July Descent to Base. Here Musheraf Din, back from his holidays, is waiting. He brought apples and needs new ski sticks.

22 July Start for first ascent of Ano Gol Zom. (The view from the top could be extremely revealing.) We set up a High Camp on Ano Gol glacier (5,700 metres).

23 July From Ano Gol Camp to the saddle between Ano Gol and Lower Gazikistan glacier, then ascent of Ano Gol Zom (6,000 metres), via southern ridge. Discovery of a promising descent possibility towards Gazikistan from the southern ridge. Whereas the saddle ends in a gigantic icefall, a passage seems to exist – though its lower end is not visible. Return by night, descending the east flank after an impressive view from the top towards Noshaq, Tirich Mir, Ghul Lasht Zom and to the Afghanistan peaks. Maybe a descent to the Upper Gazikistan glacier would be possible, too, via a small peak and the north-west flank from the saddle we reached on 17 July. (Steep. Some crevasses.) Very late return to Ano Gol Camp.

24 July Establishment of a depot (alu. box) at the Ano Gol campsite for a planned crossing to the Arkari valley at the end of our activities. Return to Konkordia and establish another depot there near the Ghul Lasht Zom group and then ascend to our old Nobaisum Base Camp.

25 July Make two heavy carries from Nobaisum Base Camp to Babu Camp (at the south-west foot of Istor-o-Nal, a very favourable position). Flowers, grass, sun, a little spring. Height about 4,900 metres. Babu was here as an Englishman’s companion, so Musheraf Din tells us. Sleep at Babu Camp.

26 July Departure from Babu Camp to Konkordia, and then along the western moraine of the Tirich glacier to the foot of Panorama Peak, erecting there a depot for our subsequent Tirich Mir Base Camp. Return to Babu Camp.

27 July Same procedure as yesterday. Now the Tirich Mir Base Camp is in place, and occupied.

28 July Rest day. Musheraf Din brings the duffel bag from Konkordia. Moreover, all the remaining material is brought from the abandoned Ghul Lasht Zom Base Camp to our new Tirich Mir Base Camp.

29 July We arrive with nearly a hundred kilos of material at the foot of Tirich West IV and establish a High Base there.

30 July Musheraf Din takes material from Tirich Mir Base Camp and carries it halfway up, from where Didi and Kurt transport it to High Base. Musheraf Din goes back to Shagrom again, another holiday.

31 July Ascend with heavy loads (twenty kilos each) from the Tirich West IV High Base (or ABC) through a broad snow and ice couloir to the beginning of the big ice balcony, leaving a cache for our camp 1 (and return).

1 August After dismantling our High Base, we climb to our cache and set up our two-man tent at 6,350 metres, protected by a rock tower. An ice lake, some two metres long, and fifty metres below saves us having to melt snow! Explore along the big balcony to where it drops away at its eastern end towards the Lower Tirich glacier. Impressive views down to the glacier, to the back of the Tirich North group and into the north faces of Tirich Mir and Tirich West. Spend a long time with binoculars scanning for a route between steep black slate and granite veins above us. The geological contact zone is like a huge spider’s web made of dykes. Sleep in Camp 1.

2 August A reconnaissance push up the north face (partly Grade IV), leaving a depot at 6,650 metres. Return to Camp 1.

3 August Transport material to the depot. Return to Camp 1.

4 August Departure from there for a summit attack. With the lightweight tent, equipment and food, we climb to the depot, and then, with heavier loads, make a long traverse on to the hanging glacier. Benighted, we stay at a very uncomfortable place (6,900 metres) in a crevasse.

5 August Transfer everything into a capacious bergschrund (High Camp 2 at about 7,000 metres), there being absolutely no other possible site for our little tent.

6 August Go for the summit. First ascent. Difficult passage around the granite bulwarks on their east side and a steep firn flank. We reach the top (about 7,300 metres) in the afternoon at around 4 p.m. Fine view to Afghanistan and closer Hindu Kush peaks. Take important photographs of the area and build a big cairn, Kurt finds some beautiful quartz crystals. Return to High Camp 2 in the bergschrund.

7 August Descend to High Camp 1.

8 August Bad weather, a real exception, not to see the sun. Extensive snowfall. Rest day.

9 August Descent from High Camp 1 with everything to the bottom of Tirich West IV. Leaving only a depot there, continue to the Japanese camp in the saddle between Dirgol Zom and Achar Zom I. Establish our own camp (nearly 6,000 metres) there.

10 August Rest day. Acquaintance/conversation with the Japanese.

11 August From the camp in the saddle ascend Achar Zom II (probably the highest in the long row of Achar Zoms, or perhaps equal in height to Achar Zom I, about 6,300 metres). Kurt – without Didi but together with two of the Japanese, Nishina and Takahashi (who is fifty-five years old) – makes the second ascent (after the Czechs). At the very top Kurt has a short fall through a breaking ice crust and is stopped by Nishina with the rope. He in turn holds Takahashi twice when he slips in the dark. Returns in bad mood to saddle camp.

12 August Kurt descends to Tirich Mir Base Camp for provisions. Nocturnal return to our camp.

13 August We go on to the High Base of the Japanese (6,500 metres) at the end of the southern branch and set up our own ‘High Base’ (One tent) close by. The Japanese politely decline an invitation to Kurt’s sweet milk and rice pudding.

14 August Ascent of Dirgol Zom (6,778 metres) by Kurt, Didi and Masaaki Kondo, a strong mountaineer not included in the Japanese summit team for Tirich Mir owing to a broken rib, sustained in a crevasse fall. Return to High Base.

15 August Didi brings up supplies from the saddle camp depot. Kurt and Kondo establish a depot for the summit push on Tirich Mir at about 6,900 metres on the slope which comes down from the gap between Tirich Mir and Tirich West I.

16 August Kurt and Kondo climb up to the depot and onto a ‘pulpit’ between two couloirs at about 7,000 metres, where they spend the night in the lightweight tent. Didi was prevented by dysentery from taking part in the attempt.

17 August Encounter descending Japanese assault team after their fruitless summit attempt. Taking care of them delayed departure until 5 p.m. Difficult climbing in the 80-metre chimney (IV, V), completed in darkness. Then by moonlight push up to the abandoned Czech tent on the saddle (7,250 metres) between Tirich Mir and the west group. Thus, no need to pitch our own tent, just crawled in theirs.

18 August Stay on the saddle. Short reconnaissance for the ascent. Masaaki barely understands English, but we manage somehow.

19 August Start at 8 a.m. for Tirich Mir summit. First follow the Czech ridge (north-west ridge) to a height of 7,400 metres, then traverse a couloir, climb a rocky face (III) to the western flank, traverse snow and blocks of rock diagonally to the right, up through the whole upper flank to join the southern ridge (where it makes its last kink), rest there for half an hour, then continue over the snowy ridge easily to the summit (but there were cornices!). Summit reached at 1 p.m. Stay there 1-1½ hours. Great view over highest peaks and an ocean of clouds. Descend by the same route, getting back to Czech tent at 6 p.m.

20 August Descend to our Tirich Mir High Base.

21 August Descend to our Tirich Mir Base Camp.

22 August Descend, just the two of us, with ninety kilos from our now dismantled Tirich Mir Base Camp to the Japanese camp at the southeast rim of Konkordiaplatz (4,900 metres).

23 August From there, to Babu Camp, and pack up. We prepare a box for the transport back to Shagrom. It remains temporarily at Babu as a cache. The remaining material is brought by us to the Japanese camp.

24 August Packing up everything at the Japanese camp.

25 August Musheraf Din appears with four porters from Shagrom and carries our luggage back there, where it is to be stored in his house until Kurt comes back from the other direction after his trip around Tirich Mir. Didi and Kurt depart for their crossing to the Arkari valley, arriving heavily laden at the depot on the Ano Gol glacier. The Ano Gol camp is set up again (with the lightweight tent).

26 August The camp is dismantled. We move everything, tiresomely struggling across big penitentes to the southern ridge of the Ano Gol Zom, and up it to about 5,800 metres. The tent is erected again.

27 August Pulling down the camp, descend over a long rib of slate to the Lower Gazikistan glacier. Along it and on to its northern moraine, to a small pool with flowers (altimeter 4,250 metres). Sleep without a tent for the first time in eight weeks!

28 August Descend to the valley of Kurobakho Gol. Kurt goes up the valley alone and climbs on the Upper Gazikistan glacier to 4,300 metres to collect geological specimens and to photograph in order to clarify the question of the old crossing from Ano Gol to Upper Gazikistan glacier. (It clearly is possible with crampons and good snow conditions. Impossible for horses. Steep.) Overnight stay in Kurobakho Gol. Food almost finished and no other humans for miles. We live on thin soup, rhubarb and wild onions.

29 August Descend out of the valley to Wanakach (3,300 metres). First inhabited settlement. Food! People are very surprised to see us.

Didi met up with the Japanese again a few days later, and when I also reached Chitral they obligingly included me as Masaaki’s companion on their official paperwork for the Tirich Mir climb.

It had been an expedition with a broad range of success: we had achieved the first ski descent of the Upper Tirich glacier and the first circumambulation of the Tirich Mir massif. We had corrected the map in the Ghul Lasht Zom area and made some important fossil finds – crinoids and the extremely rare Receptaculite, so far encountered in only nine places in the world. As for the climbing, I had made the third ascent of Tirich Mir, on a partially new route, with Masaaki Kondo; and with Didi achieved first ascents of Tirich West IV by a difficult route from the north, Ghul Lasht Zom South and Anogol Zom; the pair of us also did the second ascent of Dirgol Zom with Masaaki Kondo; and I made the first ascent of Nobaisum Zom (P6999) with Kurt Lapuch and the second ascent of Achar Zom II with Nishina and Takahashi. The total duration of the expedition had been three and a half months. However, on our return to Chitral we had every reason to fear it might take longer …

Two Chickens Come Home to Roost

Sooner or later all the knots in a thread will arrive at the comb – that is an old weaver’s saying in Italy. Sooner or later, boy, if you are up to mischief, they’ll find you out! It’s like British chickens coming home to roost though I confess, as an Austrian hearing that one over the phone for the first time, I thought it was ‘roast’ rather than ‘roost’ – what we would call a Wienerwalder Version. Audrey Salkeld at the other end of the line felt the Italian comb version more aptly described mine and Didi’s touristic foray in the Hindu Kush, although when it came to our return to Chitral, it really seemed that all three of them fitted.

We had lived – one could modestly say – as if in the good old Age of Exploration. Even my eventual encounter with the Japanese liaison officer at the end of my circumperegrination of Tirich Mir had not gone too badly: the storm, when it burst about my head, was dignified and flowery, while the local Chitrali were grinning and nodding at me, mumbling an appreciative sot zom … We had become famous with the ibex hunters and smugglers of the area. Sot zom – that means ‘seven peaks’.

However, on my arrival at Chitral, where Didi was already waiting for me, I sensed that something was smouldering. The political agent could not have been more friendly; he gave me the necessary signature and all good wishes for our return, but one of the other authorities was not so well disposed towards us. The Japanese may have helpfully declared me as one of themselves so far as Tirich Mir was concerned, but the fact that someone had climbed all over these ‘hills’, and then afterwards even gone round them, that had never happened before and appeared highly suspicious. Somebody wanted to pick a chicken, and we had just come home to roost! Or a roasting! I immediately began to tremble for my beloved stones and the photographs I had taken for the geological map – would all that effort be in vain? It was clear that we were not going to be allowed to leave here. No Jeep driver in the whole village would agree to be hired. A guard was posted outside our room. We were two quietly roosted mountaineers with a sentinel.

I was furious about the whole business, for what in the end was our mischief? I shaped a plan – and it worked. Outside the village, I engaged a lorry-driver with his vehicle, just coming up the valley, and told him that he must load all our stuff in a matter of seconds and leave immediately. There would be a bonus for this. The baffled sentry was quieted by the political agent’s signature, which I thrust under his nose, then our bags and boxes were hurled on to the lorry and we took off. The two chickens escaped! We were jubilant ... In Drosh, though, a small village further down, we found ourselves stopped by the police. After an hour of discussions, during which we refused all requests to get out of the lorry, finally the barriers were cleared. Mountaineers in Chitral had declared – thank God – that we were personal friends of the Austrian President. Apparently the telephone works in Chitral too – extremely well, indeed! The poor guard was badly punished, so we afterwards learned – but why had we been held? Did somebody suspect us of being spies? Who knows what goes on in the minds of military people. Of course, they only do their duty. I was later to be highly praised by Pakistani scientists, and a whole box of rocks – precious samples – now resides with the venerable Professor Desio in Milan.

***

Whenever I think of this expedition, a well-known Viennese joke springs to my mind ...

A man enters a pub in a great hurry and calls, ‘Quick! Quick! Give me a gin before the fun starts!’ The bartender quickly fetches him a glass, and in no time the man has drained it. ‘Quick, another one!’ he shouts, ‘before the balloon goes up!’ And he swallows that one down as swiftly as the first. Feeling better now, he smiles at the host and says, ‘Could I have just one more before all hell breaks loose?’ And the puzzled barman fills the glass again. ‘What is all this fuss you keep on about?’ With the third glass empty, the man-in-a-hurry wipes his mouth with his hand and fixes the host with an even stare. ‘The fuss is just about to start: I am afraid I do not have the money to pay you ... ’

In place of money – or the lack of it – we had a very dubious sporting permit – and the question which we put to ourselves, up there in the glacier world, was: Do we go down now or later for ‘tea’ with the liaison officer? My advice was, ‘Let’s wait a bit. Let’s grab another one before the balloon goes up. Better still, make that a double … ’ Tirich Mir!

1. The real first ascent was made 14 years later by a Spanish team. See Adolf Diemberger’s article in Himalayan Journal 29. My father was fascinated by the rugged mountains of the Hindu Kush, becoming eventually a specialist on the range, even though he had never been there![back]

2. For me this was a hard struggle as I was not yet sufficiently acclimatised to such high altitude. In the same season (1967) Doug Scott, on his first expedition to Asia, was experiencing similar difficulties in the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan.[back]