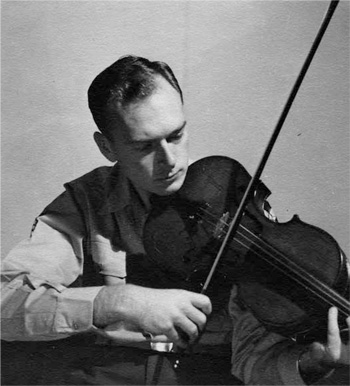

Mr. Hurlimann

My days in verdantly wet Tillamook were numbered as my father decided to return to Portland to try another trade, grocery merchant. I was twelve years old when he brought me to play for Eduard Hurlimann, the concertmaster of the Portland Symphony Orchestra. He was Swiss, and was not only a fine violinist but also a wonderful, tasteful musician. It is not an exaggeration to declare that before World War I, the most active musicians in America came from Europe—teachers, important members of orchestras, concert performers, conductors, and composers. Mr. Hurlimann was no exception, but he was a rare bird. He studied in Prague with Adolph Pick who later moved to Chicago, where he became an important teacher. Hurlimann was not a Jew, but he understood and hated Adolf Hitler with a passion before most in America knew who Hitler was. He was equally at home playing chamber music, leading the symphony violin section, or performing a concerto. Mr. Hurlimann had one of the most beautiful bow arms of any violinist that I’ve ever seen. When he played, it was as masterful as his handling of a fly fishing rod. He knew all about wild mushrooms, and was a good fisherman who loved fishing as much as I did. That caught me and I was lucky that he accepted me as his pupil.

Mr. Hurlimann said to my father, “You know, Mr. Mann, your kid is no wunderkind. He will not be a great soloist, but if he works hard and practices, I’m almost certain that he can make his living with music. I will take him as a student but you must promise that only Robert will come to his lessons from now on.”

He agreed to teach me on scholarship, and, when I was fifteen, introduced me to Bach’s solo works, including the partitas and sonatas. You might say that these are the Bible for violinists. Everyone from the great violinist Joseph Joachim on up through the years has studied them. I would come to my lesson not having practiced more than about fifteen minutes a day. I couldn’t fake anything with him. If I hadn’t practiced, he’d get very severe and would listen for about five minutes. Then he would say, “Okay, Bobby, I don’t want you to waste my time. Go home and when you’ve practiced enough, call me and I will give you a lesson.”

I was learning the Bach C Major sonata, which is a difficult one. The slow movement, the Largo, has a very beautiful and simple melody. This three minutes of music has remained a musical touchstone throughout my life. One day, I arrived around 1pm for my lesson. Hurlimann was intrigued with how I was translating the sounds into phrasing and nuances so that listeners could enjoy them, without knowing what the variation and differences were. He cancelled all of his lessons that came after mine. We spent the whole afternoon working on the third movement. He played it. He had me play it. We broke it down and studied every note, harmony, and phrase. From the opening double-stop sound (of melody and bass line) continuing the music’s course until it cadentially came to rest with its three-note broken chord, there wasn’t a nuance of phrase, any evolvement of harmony, any structural arc that he didn’t gift to me with profound love for Bach, the violin, and me. I honestly felt that I was born musically on this day. I began to think music was very interesting and started to practice more. This was the day I gave up my dream to be a forest ranger in a national park and became a true acolyte musician.

I studied with Mr. Hurlimann from age twelve until I moved to New York at eighteen. He later became the conductor of the Bakersfield (California) Symphony Orchestra, and when I was in New York, he invited me to Bakersfield to play the Prokofiev G Minor Concerto with him. It was wonderful. We continued a close relationship until his passing. If he and a few other European musicians had not worked their musical magic on me, I would have become a forest ranger (hopefully, in some western national park) or at least a potato farmer in one of my favorite places on earth, Idaho’s Salmon River country beneath the rugged Sawtooth Mountains.

I wasn’t aware that when I played, people liked the emotional message. They would tell me, “That was wonderful.” They seemed to recognize something I was totally unaware of. I wouldn’t know why. I really didn’t. I was always struggling to play better. But I was aware that music not only intrigued me, it meant something deep to me. In Portland, we had a wonderful music librarian, Miss Knox. She was elderly and very severe. Yet she liked me and she allowed me to go into the reference room. I looked at copies of manuscripts from not only Beethoven and Mozart, but also Schoenberg and Bartók. I took home six little pieces of Schoenberg and tried to play them on the piano. I would arrange the Bartók folk songs for little groups of the orchestra. Bartók and Schoenberg were both influences on my life. Later, I even took home scores by Berg, though I didn’t understand anything. At that time Berg had just finished writing Wozzeck. Ms. Knox even invited Béla Bartók to visit Portland, and he played, gave a lecture, and a demonstration on an upright piano. It is one of the regrets of my life that I didn’t get to see that.

Portland had one other important personality—a crazy Russian guy named Jacques Gershkovitch, who had fled the Russian revolution. He had not gone west like most of the Russians who were fleeing, but east to Siberia. He got to Portland and took over a little junior symphony made up mostly of students from Portland’s six high schools and from Reed College. That Portland Junior Symphony actually became quite famous throughout the United States.

I joined the Portland Junior Symphony when I was thirteen and became the concertmaster when I was sixteen. This is where I got my first experience playing in an orchestra as well as an introduction to weird repertoire. We played a stage version of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina, entire operas, and Russian tone poems by Liadov, Glinka, and other Russian composers. I met many friends playing in the junior symphony; we loved to play music together and developed lifelong relationships. We also used to sing madrigals and a cappella music and even hiked together.

In my teenage years, there were four people from the Portland Junior Symphony who were of great meaning to me. One was Isadore Tinkleman (crippled by polio) who became a great violin teacher. He studied in New York at the Manhattan School of Music with Rachmael Weinstock and came back to Portland where he started a community music school. When I was in the Army and traveled to New York I would stay in his apartment. Another friend, James Niblock (Jimmy) became a composer and later the head of the music department at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

Isadore Tinkleman

Max Felde

Also, there was Max Felde, my dearest friend who also went to New York to study viola. He was a Norseman and an extraordinary guy. He became the original violist of the La Salle Quartet, and later moved to Vancouver.

The fourth person in that group, besides myself, was a talented young violinist, violist and conductor, Warren Signer. He went to the Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia to study. When we were teenagers, Max, Jimmy, Warren, and I went on a camping trip to Tillamook, located on the most western part of Oregon that goes out to the ocean. In Portland we bought cheap ferry tickets that went down the Columbia River to Astoria. After that, we hitchhiked. That first night it rained hard, like it can only rain on the coast of Oregon. We had our supplies, but we didn’t have a tent so we put our belongings under large logs and built a fire. The heat warmed our stuff so at least it was not dripping wet and Max and I were able to sleep. However, Jimmy and Warren didn’t join us. I don’t know what they did—maybe they walked the beach all night. They came back to our campsite in the early morning while we were still half asleep and said, “We’re leaving.” They left and they took all of our food, except for the chocolate syrup. Max and I were determined to stay. We ended up living on clams and nuts and berries that we found in the forest. We stayed the week and we finally hitchhiked back up to Astoria arriving late at night. We weren’t able to take the ferry back to Portland until the morning so we needed to find a place to sleep. The hills in Astoria are very steep, much steeper than many of the hills in San Francisco. We climbed up and finally found a place to lie down. When we woke up in the morning we discovered that we had actually climbed into the Astoria Zoo. There was an animal, I think it was a moose, looking at us when we opened our eyes. We finally made it back to Portland and I hiked with Max to his house, which was about four or five miles from the ferry. Then I hitch hiked to my own home a couple of miles further, and I walked into my father’s grocery store. He thought I was a beggar and told me that he didn’t have any food. I said, “Don’t you recognize your own son?”

• • •

Another seminal event occurred while I was in the Portland Junior Symphony. For one concert held in the school’s gymnasium, that was going to feature solo and chamber music, I decided to compose a piece for the occasion. It was my first composition and was kind of a gypsy piece. After that, I kept composing. I didn’t study any formal theory. But I knew there were fugues, so I would compose a fugue without knowing any of the rules. I also wrote a long sonata, following a Bach solo sonata, for a girlfriend who was a cellist in the Junior Symphony.

Robert at the beginning of his musical career