Wanting to be a chamber musician

There were two realities for my wanting to be a chamber musician. Musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern, and Ruggiero Ricci would come and play concerts in Portland. I knew, and Mr. Hurlimann knew, that I was never going to be a great solo violinist. I didn’t have the chops to play, to control the instrument in that way. I also didn’t have the desire.

In my early days in Portland there was a hall in a labor building called The Neighbors of Woodcraft. It was a beautiful hall and had beautiful acoustics. As an adolescent I used to sneak in to hear the Budapest Quartet, the Pro Arte Quartet, and other groups. They all came to Portland on concert tours. I was inspired.

In Portland, Howard Trugman, the manager of the symphony, loved to have kids come to his apartment and play. I had a group and we read at least once a week all of the chamber music that we could get our hands on (and Ms. Knox, at the Portland Public Library, got all of the music for us). Haydn wrote oodles and oodles of quartets, and so did Mozart. Beethoven wrote sixteen quartets and so on. It seemed to me, since I was quite good at reading classical chamber music, that I could be a chamber musician.

New York and the Institute of Musical Art

When it became time for me to study elsewhere, Mr. Hurlimann, who was a very bright man, said that I had to go and study in a very sophisticated city where music was more meaningful than in Portland.

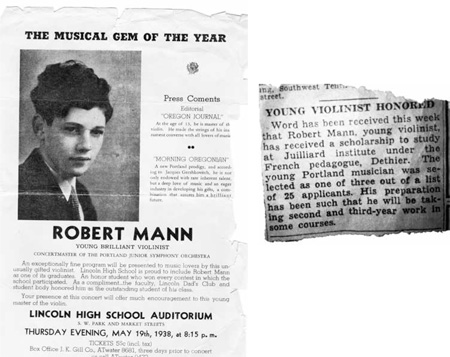

At this time, for serious young string players, there were two outstanding schools to go to for study, the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and the Juilliard Graduate School in New York. Both were free at the time. At age eighteen, I sent my application to the Juilliard Graduate School and was accepted into the Institute of Musical Art (which later merged with the Juilliard Graduate School to become the Juilliard School of Music.) I can’t tell you why I chose New York over Curtis. I think I thought I wasn’t that good, and that it would be easier to get into Juilliard than Curtis.

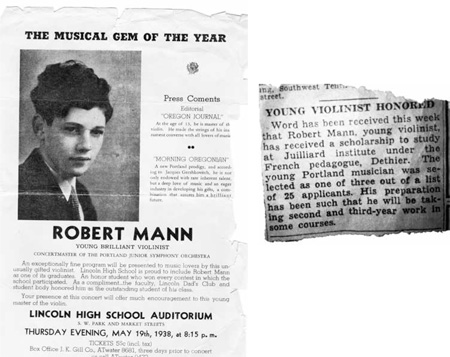

High school concert publicity

We were a poor family, so I played a concert in my high school, Lincoln High School, to raise money for my studies in New York. I was playing a violin that was given to me by my English teacher, Miss Frances Gill, whose family owned the big paper, stationary and furniture store in Portland. She gave me a violin to take to New York. It was old and she thought it was a Guadagnini, but it wasn’t—it was an old Tyrolean violin and I still have it. A very wealthy lady, Edna Holmes, came to the concert with a Ms. Rothschild, who was supporting young musicians. They felt that they had to support me and were able to raise enough money on my behalf. Ms. Holmes was a marvelous lady. Not only did she provide most of the money for my going to New York, but she also sent me $80 a month throughout my student days in New York. Even later, when I was married, she would send presents to the children. Later in life I wrote a letter to her saying, “Edna, you’ve been one of the most meaningful people in my life and I want to repay you now.” She replied, “Don’t repay me, you continue to help young people and I will be repaid.”

I always loved peanut butter and everybody knew it. So when I got to the train for my send-off to New York, about five mothers were there who all produced boxes of peanut butter cookies for me to take across the country. I traveled via Washington state to Vancouver and took the Canadian train across the country, down to Minneapolis and east to New York.

I was met at the train by the husband of my mother’s cousin, who was a rabbi in Mount Vernon. Then I had to find a place to stay. Mrs. Howard Brockaway, who was the placement person at Juilliard said, “There is this absolutely marvelous family and they have a daughter who is a wonderful young violinist, Carol Glenn. The mother runs a couple of apartments where she rents out rooms that are affordable for students. You should go there because it’s very homey and it’s your first year away in New York.” So I went there.

When I arrived at the Institute I had to take exams, and the first thing that happened to me was that I failed them. They wanted to know if I knew what a Neapolitan six was, if I knew all of the modes, or whether a given chord was major or minor, this or that chord form. While I knew all the chords and their functions, I didn’t know any of their technical names. I was placed in the first year. Within two weeks I learned all of the names and the teachers stuck me in the second year and by the third month I was in the graduating class.

My teacher, Edouard Dethier, was from Belgium. I wanted to study with Louis Persinger. All young kids wanted to study with him because he had taught Menuhin and Ricci. But I couldn’t because I hadn’t been assigned to him. Dethier had studied at the French conservatoire and with the great Belgian violinist, composer and conductor Eugène Ysaÿe. At that moment, being assigned to Dethier was the luckiest thing that ever happened to me because Dethier was a continuation of the path that Hurlimann had sent me on. Not only did Dethier have a perfect technique but he loved chamber music. He was a passionate, wonderful, warm, and rather shy man.

I loved my studies with Mr. Dethier, although he had a certain idiosyncratic way of teaching which I often rebelled against. He would say, “You’re going to study such and such composition. Go to Carol, or go to another student, and copy the bowings and fingerings.” I wouldn’t do that. I would struggle through the piece and make my own bowings and fingerings. When I went to my lesson he would say, “Well, didn’t you copy the bowings and fingerings?” and I would reply, “Mr. Dethier, I didn’t really want to do that. I wanted to find out for myself.” He would say, “I’m trying to save you time. I mean I’ve gone through all of these struggles.” And I would say, “Yes, but I need to go through those struggles, too.” His reply in his fantastic French accent, “You know, I get so mad at you. I could take my fingers and pluck out your eyeball, spit in the socket and let it splash back.”

Every Friday, Mr. Dethier would play string quartets for his own musical health. He played in a quartet with a female student on second violin and a cellist by the name of Bedrich Vashna, who was much older and had played the Dvořák concerto in Prague, with Dvořák conducting. Another requirement in Juilliard in those days was for violinists to also learn viola. Juilliard didn’t have a viola department. Dethier’s quartet needed a violist and since I could also play viola, I was elected.

So, every Friday we would play for three hours, have refreshments, and play for a couple hours more. I learned all of the chamber music repertoire from pre-Haydn into the twentieth century during these sessions. Dethier didn’t get past Dohnányi, he didn’t understand Bartók or anything modern, but he did love Debussy.

Dethier had a house in Blue Hill, near the Blue Hill Music Festival, which was a gathering place for many important musicians. In the summer, I would go there to study with him. Franz Kneisel also had a home there. Kneisel was a friend of Dethier’s who had also been a friend of Brahms, as well as the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony in the nineteenth century. He was America’s first serious quartet player; his quartet was the first to play the complete cycle of Beethoven quartets in the United States. It was at Blue Hill that I also met the legendary violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler for the first time. Kreisler was a very strange and funny man. He never touched the violin all summer. He would study a piece without practicing it and then play it in a concert.

That summer I also met a man who was very important in my life, Stefan Wolpe. He was at Blue Hill composing and he had a whole group of students with him. I would join his group and read music. Wolpe had a theory that you could read contemporary music and develop skills for playing it. I really became enamored of this man. I didn’t officially study composition with him, but I would compose a piece, bring it to him, and he would criticize it. He was an important influence on my compositional development.

Stefan Wolpe

My first theory and composition teacher was Bernard Wagenaar, who was a Dutchman. He could play any score on the piano. But I also remember studying the Bach chorales with Judson Ehrbar, who later became the Registrar at Juilliard. Ehrbar gave us the melody, an old Lutheran melody, and our job was to harmonize it. He was young and didn’t really know that much. He would put out the Bach score to show us what Bach had done with this melody, and then he would take our harmonization and put it up next to Bach’s work. The red pencil was going all through our work all of the time, and after three or four lessons I got tired of that. I made friends with the librarian at the New York Public Library’s music division, located at 58th Street on the East Side. I knew that Bach had harmonized many chorales more than once, and I asked her if there were any other editions than the one that Ehrbar was using for his teaching. She took me to the reference area and found them, and I begged her to let me check them out. She agreed that I could have them for a week, on the condition that I didn’t tell anyone. I found the assigned melody and copied in my handwriting Bach’s other version out of the book. I went to class, and Ehrbar did his usual teaching and crossed out everything in red that I had copied from Bach’s other score. Finally, when he finished his red markings, I took my borrowed book with Bach’s alternate harmonization and said, “Would you put the red pencil through this book, too?”

Of course this was a terrible thing for me to do. Ehrbar got up after a minute, left the room and was gone for about twenty minutes. When he came back he said that Mr. George Wedge, who was the head of the school and had written a famous harmony book, would like to see me. I was sure that I was going to be thrown out of the school. Mr. Wedge was behind his desk busily writing and didn’t say anything to me for at least three minutes. Finally he said, “Sit down, young man.” He was smiling, and said, “Now look, all of us are learning, even our teachers. You shouldn’t put a person in that kind of position. That was rough, but since you seem to know what you are doing, I’ll excuse you from the class. You will just take the exam at the end of the year.”

I studied quartets with Hans Letz who came to the United States with Franz Kneisel, and played in Kneisel’s quartet. I remember an instance when my quartet was in Hans Letz’s studio having a quartet lesson. He had picked up four pieces by a Dutch composer, Julius Hijman, who had fled the Nazis. Hijman was going to have a concert of his music played at Carnegie Recital Hall, and he hoped that a student quartet would be willing to play on this recital. The work was very complicated, there wasn’t a harmonic scheme that we could conceive of, but we were playing it. In walked Felix Salmond, the great cellist and chamber music musician, who listened for a while and said, “Enough of this. How can you let your kids play this, Hans?”

Hans began to retreat and said, “Well, perhaps we will tell the gentleman that we won’t play the work.” I was upset and found out where Mr. Hijman was staying so I could call him. I said that Juilliard wouldn’t help him with his performance, but if he wanted, I would ask three of my friends and we would perform the work, and we did. The reason that I tell you this story is that Mr. Hijman got a job so very quickly afterwards at the Houston Conservatory of Music, teaching theory and composition. When he left New York, he had to leave his upright piano and he offered it to me. I’d gotten my first reward for playing a contemporary piece.

The discipline of chamber music

The discipline of chamber music emerged in America when I was a student1. Before World War I, many people played chamber music in Europe, but mainly amateurs who held evenings where they sight read quartets, trios, and quintets, and maybe even sextets. When I came to New York and I needed money desperately to study, I learned the underground way of making a kind of student living was to play in amateur chamber groups. There was a strong amateur society in New York and I knew the lady who ran it, Helen Rice. She was marvelous and I would join her group as a violist or second violinist when she would play with her friends. We would spend the evening, at least three or four hours playing chamber music. The groups usually needed violists, and I could play viola quite well, so I got a lot of jobs and would earn $50 for spending an evening playing chamber music with these amateurs.

But I was a lousy student. I was discovering New York and didn’t practice much that first year. At Carol Glenn’s house, where I was living, there was a jazz fellow who was learning classical harmonization, and we used to go to his room and sit around. We would listen to a radio show called Lights Out. At around three o’clock in the morning we would go down to Blenheim’s cafeteria and have what we called the one-eyed Egyptian sandwich, which was an egg fried in the middle of a white piece of bread.

It was a terrible year for developing my violin playing but a wonderful year of growing up and, unfortunately, getting an ulcer. One man, Conrad Held, who was on the Institute faculty and taught violin and viola, wrote in his notes on my end-of-the-year jury, “Never in my whole life experience have I ever seen such a talented well-prepared young man deteriorate so much in the space of one year.” I never forgot that. And, I did manage to pull it together, practice a bit, and graduate from the Institute of Musical Art that year.

After graduating, I didn’t want to go home to Portland. I learned about an interesting spot near Tanglewood named South Mountain, which was the estate owned by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. There she had sponsored and commissioned the Webern string trio, the Third String Quartet by Schoenberg, and other pieces. Maestro Willeke, the conductor of the Institute of Musical Art’s orchestra, was there; he invited faculty and students for a festival of studying and playing chamber music at South Mountain. Since they needed a violist and I was willing, I was in demand again. I ended up spending that summer at South Mountain, practicing and trying to improve my technique before taking the exam to enter the Juilliard Graduate School.

After that, it was time for me to play for Mr. Dethier before taking my exams. He was very upset because he thought my Bach was terrible. I had also prepared the Beethoven concerto with the Kreisler cadenza. At the exam, they would ask you what you wanted to begin with so I chose the Beethoven concerto. I played a good part of the first movement and then I was asked to play Bach. My heart sunk because I knew that my teacher thought it was terrible. Someone else said, “No, I’d like to hear the cadenza.” I was in luck. Afterwards, Mr. Dethier said, “God is kind to fools and drunkards. I wonder which you are.” I got into the Juilliard Graduate School, but I was still more interested in chamber music than I was in solo violin. I must have been involved in at least four chamber music groups at that time.

At Juilliard I loved to play in the pit ensemble for the operas. That was a marvelous way of getting to know Mozart’s operas. I also loved playing in the orchestra. Most of the students tried to avoid playing in the orchestra. Lynn Harrell was one of the only successful soloists who talked about going back at the end of his life to play in an orchestra again, because he loved it so much.

I remember an orchestra concert conducted by Alexander Siloti, a crazy Russian. We were on stage waiting for him to come out. We waited for five, ten, then fifteen minutes. Everyone was wondering what was going on and finally somebody went backstage to find him. He said, “I won’t come out until Liszt tells me it’s okay to come out.” Some of his pupils would come to a lesson and recalled that he would say he talked to Liszt down at Columbus Circle.

Albert Spalding also taught violin at Juilliard. He was maybe the first famous American violinist. He was a member of the family that sold all of the sports equipment including the Spalding tennis balls.

I played sonatas with Billy Masselos who was a student of Carl Friedberg. Other friends included Willy Kapell, who studied with Olga Samaroff Stokowski. Willy Kapell was different than the typical student. His language in those early days was tempered with a lot of epithets and he had a short fuse. I remember we studied sonatas with Louis Persinger. Since we were both busy doing so many other things, we would get together about two hours before our lesson and run through the sonatas. Then we would arrive to play for Persinger and pretend that we had worked all week on the sonatas. Of course we hadn’t. It didn’t take Persinger long to catch the drift. After three or four lessons we came in with the Brahms G Major Sonata. The sonata starts out with a G Major chord on the piano, two of them, and then the violin comes in. Kapell played the two chords and I came in. Persinger says, “Wait a minute, wait a minute,” and he spends the whole hour on me and the upbeat. Willy sat fuming, waiting and not being able to play.

In those days at Juilliard, students had a curfew. You had to be out of the building by ten o’clock at night. Willy and I would hide in the cleaning closets until the guards had gone through the school to make sure that everyone had left and we would stay all night and practice. I remember Willy used to practice Scarlatti so furiously that his fingers would bleed.