When I was a student in New York, there were the Naumburg and Leventritt Competitions in New York and the Schubert Memorial that took place in Philadelphia. In Belgium there was also another great competition, the Queen Elizabeth.

The Naumburg Competition, named after Walter Naumburg, an amateur cellist and avid chamber music player, was a competition for soloists. It gave the winner a concert debut in Town Hall in New York City, completely free. Mr. Dethier said, “You know you’re not good enough to win the Naumburg but it would be a good experience for you to try out.” Virtuosos from all over the country entered the competition. Most of the players were so much better than I was. In those days, the Naumburg included several different instruments and voice in the competition. In other words, Walter Naumburg started his competition for any talented young solo musician. Later, Lucy and I, in our roles as Naumburg President and Executive Administrator, would add chamber music to the array of competitions.

I practiced all the requirements but didn’t take it seriously. If I would have, I would have dropped out. You were required to have two complete solo programs and a concerto. My program included a Nardini sonata, the Bach partita in D minor and the Chausson Poeme. My concerto was Prokofiev’s second concerto, the G minor, and when it came time for the competition, I only knew the first movement by memory. The judges wanted to hear everything you played. If they were nice in the beginning, they would ask, ‘What would you like to start with?” Luckily this happened and I said very politely, the first movement of the Prokofiev concerto and I played it. I was hoping that the judges would immediately go to another piece because they wanted to hear me play Bach and so on. It worked, and I didn’t have to play the last movement. I got into the semi-finals, which were held a week later. I killed myself and memorized the Prokofiev concerto so I could get through the slow movement. It was the last movement that was a problem for me. It’s a rondo and very brutal and I wasn’t confident playing it.

Also making the semi-final round were six other violinists—all girls. The semi-final round also had a different jury. So when they asked me, “What would I like to start with?” I said, “The first movement of the Prokofiev concerto,” and that was fine. All of a sudden a member of the jury said, “You know, I’d like to hear the last movement of the Prokofiev.” I turned to my pianist, who had gone on tours with Paul Robeson and William Primrose and had a funny sense of humor. I turned to him and asked, “What do I do now?” He said, “You have two options. You can say you don’t know it and they kick you out. Or, you can start playing and stop when you have to.” God’s truth, I went through and as I reached the end of the part I knew, the judges said, “thank you.” I just couldn’t believe it. Next the jury wanted to hear the Chaussone Poeme. I made it to the final round.

The final round took place at Town Hall, a performance hall in midtown Manhattan. In the finals were a number of violinists as well as other musicians in other disciplines. Willy Kapell made it to the finals. There was also a young man from The Curtis Institute, a violinist named Rafael Druian who had a fantastic technique; we all thought he would win. He later became the concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell.

At the finals, a lady juror who I learned later was one of the great lieder singers of the day who was famous for her singing of Debussy, asked, “You have this Nardini sonata on your program. What is that?” I explained that Nardini was an Italian Baroque composer from the early eighteenth century. She asked me to play the larghetto movement, the slow movement of the sonata. The one thing that I could do well was to communicate warmth in my phrasing, the reason anyone listens to this kind of music. The lady juror later told me that they recognized that the other violinists had better technique and were much better, but no one communicated the slow movement the way I did with the Nardini larghetto. Two winners were chosen in the 1941 competition—Willy Kapell and me. Playing that movement was the reason I won the Naumburg competition.

My teacher’s response to my winning was what he always said, “God is kind to fools and drunkards. I don’t know which you are.” He was amazed.

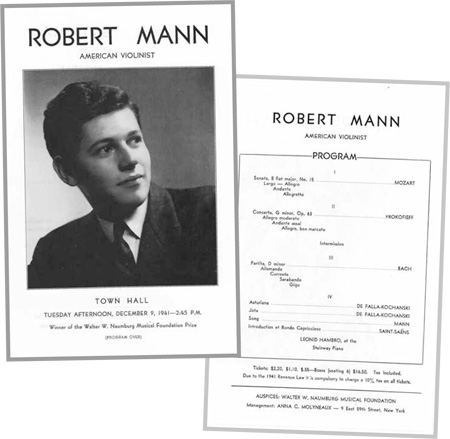

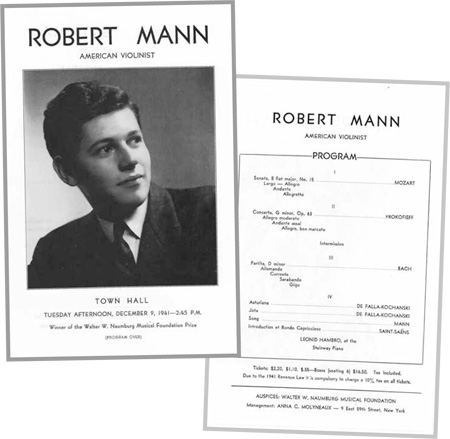

Town Hall debut program (front and back)

I played my debut in New York City’s Town Hall on December 9th, two days after Pearl Harbor. The program included the Prokofiev concerto (you had to play a concerto on your program in those days). I opened the concert with a Mozart B-Flat Sonata and an American contemporary piece that I wrote. That was a Naumburg requirement that you had to play an American work. My pianist was my very good friend, Leonid Hambro.

Since Pearl Harbor had taken place two days before, a third of my audience was scared that New York City was going to be bombed. People were directed to stay in the basement of buildings downtown. A third of my audience didn’t even get to the concert, so I didn’t have a full house. However, my mother came. After my concert, I got reviews from all of the New York papers, Brooklyn too. I mean every single one. And by the way, all of my reviews were wonderful2.

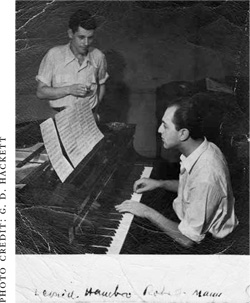

Robert and Leonid Hambro

After winning the Naumburg, I played the Prokofiev concerto with Albert Stoessel conducting. That performance of the Prokofiev was played note perfect, the whole piece. I don’t know why. I’d never done that before and I’ve never done it since.

Another story involving my friend Leonid Hambro took place after he won the Naumburg himself in 1946. Lee asked me to compose a piano work for him to play as his American piece. At the concert, I was sitting in Town Hall with his teacher, Rosina Lhevinne. Lee had decided that he was going to perform his entire concert from memory. He got to my piece, which starts with a two-minute slow section followed by a very fast section that lasts about six minutes and then a short coda. During the fast part, he became unbelievably lost and started to improvise. I thought why don’t you stop, go off the stage, get the music and play it with the music. But no, he kept improvising, trying to figure out what to do, which had nothing to do with the piece that I had written. Finally, he jumped to the coda, which he remembered and finished the piece. Ms. Lhevinne turned to me and said, “Lovely piece dear.” I was dying. It wasn’t my piece at all.