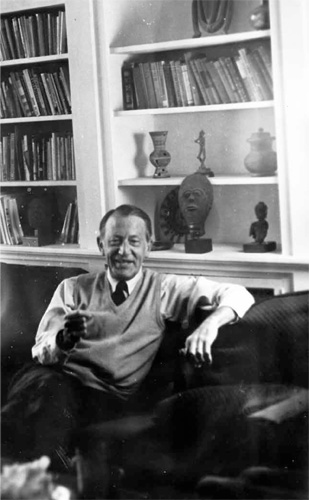

Felix Salmond (1888–1952)

One of the first important musical mentors of mine during my Institute years was the eminent cello teacher Felix Salmond. Salmond taught at both the Juilliard Graduate School and at Curtis, and had taught everyone from Leonard Rose to Frank Miller, and all of the up-and-coming young American cellists. He was a great musician in the old-fashioned sense. Anyway, he fell in love with me. I was in many chamber music groups that Mr. Salmond coached. I remember playing trios with the duo-pianists Arthur Gold and Bob Fizdale. I also played in quintets and sextets. Under Salmond we were inspired to play way beyond our abilities. It was Felix Salmond who was inspiring us to play. Salmond also recommended me to play the Beethoven concerto with the Juilliard School orchestra. He played trios with the Lhévinnes—Rosina or Josef—and he invited me to be the violinist. We even played an evening concert in someone’s house, and that was wonderful.

My piano is Salmond’s. When he died, Salmond’s widow knew how much he loved me and I loved him and offered his piano to me at the bottom price instead of just selling it to anyone. So I bought it. I still have it to this day.

Felix Salmond

I learned from Salmond what is important about teaching and what is not important about teaching. You have to draw the people out on their own. You have to learn how to inspire people so they can light their own fires rather than be put on fire by you. That is a very important basis for teaching and I learned this from Felix Salmond.

Eugene Lehner (1906–1997)

Eugene Lehner was a heavenly force. No person shaped so many others in chamber music art as did this man. Multitudes of musicians, young and old, will respond “amen.” This beloved legend—husband, father, violist, mentor, philosopher, vegetarian, curmudgeon, self-doubting, ego-strong, frail Hungarian giant arrived on the tide bearing marvelous musicians fleeing the Nazi terror. With his beautiful Danish wife, Lucca, and son Andreas, he chose to live in the Boston community when offered a position in the Boston Symphony. Playing in an orchestra was a very small part of an extraordinarily meaningful music life. His own coming of age was shaped by the master musicians of the Liszt Conservatory in Budapest (Leo Weiner, Zoltán Kodály, and Béla Bartók) and later, his life in Vienna with the Kolisch String Quartet where he participated in the creative musical ferment led by Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Rudolph Kolisch, Edward Steuermann and a large group of believers. This profound background, which was tempered by thirteen years in the Kolisch ensemble performing the quartet literature from Haydn through Schoenberg without benefit of music in front of him6, was what he brought to Boston and Tanglewood, inspiring as a teacher and friend, all of us who were lucky to come under his sway. He was the greatest musician I’ve ever known and he always made little of himself.

I remember vividly my first encounter with this musical oracle. I was not quite twenty-six years old. Robert Koff, Arthur Winograd, and I were desperately searching for a violist to complete the quartet. After a number of unsuccessful sessions with a number of violists, Winograd suggested this fellow in the Boston orchestra who he had studied chamber music with at Tanglewood. He was older than we, said Winograd, but a fabulous musician and person: Eugene Lehner.

On the occasion of a Boston Symphony concert in New York, Mr. Lehner joined us for an afternoon of quartet reading. He specifically requested that we play Opus 130 Beethoven with the Grosse Fugue, the second Bartók and the third Schoenberg quartets. It was love at first hearing. This magician of the musical art captured us totally without trying. I begged him to become a member of our quartet. Soon after he wrote a “dear Bob” letter. He confessed that he loved playing music with us, but he dwelt on his thirteen-year age difference and how this change would be difficult for his wife and son. However, he did recommend Raphael Hillyer, then a 2nd violinist in the Boston Symphony who also played with him in the Stradivarius Quartet. Hillyer, like many of us, played viola as well as violin. Alas, we never got Eugene Lehner as a member of our quartet, but more importantly, we gained a mentor whose role in our development was immeasurable. Every composition that we studied during our early years was defined, illumined, and inspired by Lehner’s unerring insight, imagination, and mysterious faculty of remaining open to new, provocative revelations not even thought of before by himself. In Eugene Lehner, I found my musical father. I was never with him a single time when some new or unexpected musical thought didn’t surface. Unlike a mining operation, this musical resource was unending. His fame as a chamber music teacher spread like a prairie brush fire, but never burned out. He drew young musicians from all over the world. The music schools in Boston gloried in his ongoing attention. Ensembles such as the Schoenberg Quartet from Amsterdam and the Mendelssohn in New York grew very close to him as did the many students who coached with him every summer at Tanglewood.

Eugene Lehner was the real mentor and the meaningful basis for the growth of the Juilliard String Quartet. I remember once we were playing the Schubert A minor quartet. The minuet is a ghostly character, Schubert at his most distant and inner voice. There is something about it that rings bells if you keep it “inside” rather than play it “outside.” Lehner sang that movement from beginning to end while lying on the floor. I’ll never forget the sound of his voice. It taught us more than any words ever could. Another time at Tanglewood, he was teaching the very tragic Bartók Sixth Quartet. The quartet starts with a mesto or “deep sadness” which is an introduction to all of the movements. The rest of the quartet is very bitter and finally the last movement resolves into a complete mesto. He wasn’t getting across what he wanted. All of a sudden, this tall, gaunt, marvelous man drops to the floor on his face, lying there like he was dead. The quartet got up and they didn’t know whether they should call somebody; they think that he may have died from a heart attack. When they are thoroughly hysterical, Lehner turns his face and says, “Mesto! Mesto! Mesto!”

Eugene Lehner

As Lehner grew older, he never faltered, never lost the enthusiasm or vigor of involvement with the musical scores or the ensembles mesmerized by his way with them. He was simultaneously the musician who knew everything while strenuously asserting that he knew nothing. He was indeed a reincarnation in music of Socrates. His lifelong attachment to music in no way isolated him from his passionate engagement with all art, culture, societal concerns, literature, science, philosophy, religion, and most of all family and dearest friends.