Germany and Hanns Eisler

I had never met the composer Hanns Eisler, but I did like his music. Eisler was born in Leipzig, Germany, the same year as my mother in 1898, and his family moved to Vienna in 1901. He eventually studied composition with Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern. In 1925 he moved to Berlin where he began to work closely in the theater with Bertolt Brecht. His left-leaning political views estranged him from his Vienna teachers but their influence remained ingrained in his marvelously crafted compositions. He later composed for film as well as the anthem for the German Democratic Republic. Hitler came into power and Eisler moved to the United States, first to New York City and then in 1942 to Southern California where he worked again with Brecht and taught composition.

Hanns had one hell of a problem, not of his own making. His brother, Gerhardt, ran the United States Communist Party. Don’t forget Joseph “Savonarola” McCarthy and his witch hunt for “communists” in the United States. Gerhardt was going to be prosecuted and he jumped onto a London bound ship and then onto a Polish boat and escaped before he could be arrested and brought back to America. He was just steps ahead of justice department officials, escaping arrest and trial. Hanns wasn’t a U.S. citizen and lived silently in the California hills. No matter where he went, he was legal game and the government wanted him to leave. The ruling—because of his brother, Hanns Eisler must leave the United States.

A number of Eisler’s friends wished to send him off with a meaningful gift—a New York concert of his compositions in Town Hall. On the program was a string quartet played by our colleagues, the New Music Quartet. We admired the work and went backstage after the concert to tell Eisler. “You naughty boys,” he remonstrated. “Why Hanns, what have we done?” we asked. “The Juilliard String Quartet refused to play my work! Why did you refuse to play my quartet?” We didn’t know anything about it and said, “But Hanns, we haven’t the slightest notion of what you are referring to.” Later our quartet learned that the organizers of this evening’s concert had approached the Juilliard School asking for our participation. Without telling us, Mark Schubart, Juilliard’s dean at the time responded, “Absolutely not!” I was outraged and apologized to Hanns profusely. “Good luck, Hanns, in your new life.” He was returning to Germany and I had no idea if it was East or West. He smiled and said, “If you ever come to Berlin be sure to look me up.”

One year later, it was the early 1950s, the Juilliard String Quartet was rehearsing in our room at Juilliard across from Grant’s Tomb when the door quietly opened. A tall, thin, arabesque of a fellow glided in without knocking. His voice was ghostly soft. “My name is Matteo Lettuni. I am the cultural affairs officer in West Berlin.” At this time, Berlin had different sectors. There was the American sector, the Russian sector, and so on. We waited silently and he continued, “The three Western powers—England, France and the United States—have committed themselves to producing a West Berlin cultural festival. Each nation will send its best artistic, cultural representatives to take part. For the first time in our country’s history, a United States president (Mr. Eisenhower) would designate presidential funds to send our nation’s artists to this festival. We listened and wondered. This is 1951, nobody knows us. Why do they want us?

Mr. Lettuni read our questioning faces. “Those of us organizing the U.S. participants are well aware of your great success with the BaLrtók string quartets at Tanglewood. We would like you to represent the chamber music for the festival and include some concerts by your quartet. We will also be having Judith Anderson in a company doing Medea and Celeste Holm in Oklahoma.

All four of us were performing silent cartwheels of happiness—our first opportunity to play in Europe! And to think, what a prestigious circumstance! We had never been to Europe. Our acceptance was in unison and word soon spread through Juilliard about this wonderful invitation.

And then all the Israeli kids heard about us going to Berlin. There was a big clamor and one of our favorite chamber music students came up to us shyly, speaking in a most distressed and uncomfortable fashion. She said, “You know that there are about 35 of us Israelis at Juilliard and all of us are very upset that you are going to Germany. Can we meet with you?” Not one of us had given any thought to non-musical implications. Here we were, four American Jews excited about playing our music for audiences who just a few years previously had been clapping for Nazi-approved music played by Nazi-accepted musicians. To the young Israeli student we replied, “Yes, we will meet with all of you.”

Our studio was packed, standing room only. A young man spoke, “You must know that you four members of the Juilliard String Quartet are amongst our most favorite teachers. We are horrified that you are going to a land where many of us escaped with our lives and many of our families did not make it. My parents died in the Dachau camp. How can you good persons, even Jews, consider playing for those people?”

The following discussion was pure agony. Not one of us had any answer for the group of young people whom we loved. Lamely, we countered their protest. “You know, we aren’t going to make music for the German people. We are representing our own country, the United States.”

It was a long and painful meeting. We ourselves had doubts but the students made it crystal clear. More than half of them declared, “As much as we treasure our relationship with you, if you choose to go, we will have nothing more to do with you.” We were conflicted and torn in two directions. We rationalized and finally decided to make the trip. True to their word about half of the Israeli kids turned their backs on us and quit our classes. And, also angry at us was one of the leading cello teachers, Uzi Weisel. Interesting enough, I later received a letter from Weisel apologizing for his behavior because he had since traveled with the Israel Philharmonic and had played in Germany.

Still troubled, but bursting with curiosity and the opportunity to play in such auspicious company, we now happily settled into a big, West Berlin hotel. I was with my love, Lucy; Winograd, our cellist, brought his girl, Betty. Dying to make some connection to this new world, Lucy asked, “Doesn’t Hanns Eisler live here?” We stared at each other. “But doesn’t he live in East Berlin?” “Yes, he does and I think he is teaching composition in the East Berlin Hochschule fur Musik.” (Remember this is 1952 and there was no Berlin Wall.) “Well, how would we find him, get in touch?” Lucy, always the practical one, suggested the telephone book. Slowly, slowly we turned pages and sure enough in small print—Hanns Eisler—with a telephone number and address. Shall we call? We were on an adrenalin high. After three rings a female voice barked, “Hello.” I responded, “Herr Hanns Eisler?” “Ein moment.” Twenty seconds later I was talking to Hanns Eisler.

“How wonderful that you are here in Berlin. Why don’t you come over for a visit?”

“That would be great, but Hanns, we are in West Berlin and you are in East Berlin.”

“No problem,” said Hanns. “Take the Ubann across the border and then grab a taxi to this address.”

“But Hanns, the East German marks are different.”

“Oh don’t worry, East Berlin taxi drivers love West German marks.”

Without thinking and full of anticipation, Lucy, Arthur, Betty and I took the subway and arrived at a square in East Berlin. Sure enough, there was no difficulty. The four of us were conveyed in a somewhat dilapidated Mercedes through a quiet, green foliaged section of Berlin, one stately mansion after the next. Time stood still. Had there really been a devastating war destroying many countries for many years? We reached the tall old world house surrounded by century old trees, a well-cared lawn and profusions of flowers, where Hanns Eisler and his wife lived. Hanns answered the doorbell. Hugs and warm communications filled out the time and space of our visit. “Hanns, you and your wife seem to be living the good life.” He laughed with his whole body. “Couldn’t be better. I teach serious composers at the Hochschule, I live here with a maid, a gardener and any extra help I need.” (I wondered to myself—this is communism?) It was getting late and we should have been going back. The doorbell rang. In came a couple, the man looking very much like his brother. It is Gerhardt Eisler, the Propaganda Minister for all of East Germany.

My guess is that all four of us were a little uneasy. We were introduced. Hann’s brother was not a diplomatic personality. We hardly met and he was accusing the four of us, “You support General Marshall. You are enemies of the people.” We got into a political argument with this man, at which point, he was talking and getting very red in the face. We finally got a moment between angry breathing and Arthur Winograd asked, “You know they’re reporting that in China there have been ten thousand people killed because they are anti-communist or anti-Revolutionary. What about the thousands of Chinese being executed for anti-government bias?” (Communist Russia was at this moment buddies with Communist China.) Long silence—then with a lion’s roar, Gerhardt Eisler shouted, “We are trying to create a world where all people count and even if more than thousands resist our action, we must persevere! We’re trying to do something good for the people. If it means we have to get rid of some people, we have to. We’ll kill fifty thousand people if we have to.”

Total, lengthy silence—“would anybody like some tea?” timidly offered Mrs. Hanns Eisler. As soon as we could, a taxi took us back to West Berlin. We were not very presentable, unshaven and wearing jeans. We were greeted by an urgent telephone call from our friend and sponsor Matteo Lettuni. “Where the hell have you been? Everybody, and I mean everybody—English, French, Americans and Germans are over at this other hotel for a big news conference. Get over there without delay!” “Yes, Matteo.” Not bothering to change clothes or shave we anxiously hurried over to this new hotel. Completely out of place, looking like bums, we saw Matteo and like delinquents, we apologized. He looked as if he would send us back to America on the spot. “Where have you been?” I cannot explain to you, the reader, how dumb or naïve was the reply. I say, “Matteo, you will never guess who we were visiting.” I told him the entire escapade and add terror and confusion to his already raging facial expression. A full minute elapsed before he opened his mouth. “Let me warn you, that the money that brought you here from the president’s fund is with congressional approval. If anyone in our government hears about this, there will never be another cent spent by the president for such an occasion again.” And, he added, “Quite possibly you might be accused of traitorous behavior.” Sorry Hanns, but we weren’t so clever. However, all good compositions, happy or sad, or neither, have a coda:

Winograd and I, with our loves, had just come out of the auditorium onto the street. We were thrilled with a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony played by the Berlin Philharmonic under the great conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler, assisted by wonderful singers and a rousing triumphant chorus celebrating the brotherhood of human beings. We stood on a Berlin street corner sobbing our hearts out, uncontrollably.

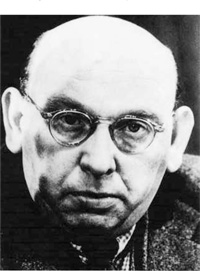

Hanns Eisler

Frankfurt

After we played our Berlin concerts we arranged to play a number of concerts in what in those days were called America Hauses in Germany. We played in Frankfurt and other cities. Claus Adam had a friend who was the Consul General for the United States in Frankfurt and after we played in Frankfurt we were given a party. We were taken around in a big Volkswagen station wagon. I had Juilliard’s Guadagnini violin and the other three quartet members also had very good instruments with them. A man was charged to take us up to the party and said to us, “You don’t have to worry, the driver will stay down here the whole time and watch your instruments.” So we went up and when we came down after the party all of the instruments were there except for my Guadagnini. It was gone. So I looked at the driver and asked, “What happened? Where is my instrument?” He sheepishly admitted that the wife of the Consul General came down to check on him and invited him to come up and have a sandwich. So he went and someone had stolen my violin. What was I to do? It was a Juilliard Guadagnini. We wanted the theft to be reported in the American and German newspapers. We went to the military policeman who wasn’t interested in a stolen Guadagnini violin at all, because he was a homicide man. Then he heard that it was worth $10,000 and had it printed in the newspapers.

The next place we were going to was Stuttgart and in Stuttgart there was a very famous violin dealer by the name of Hamma. He was called and it was arranged that he could loan me an instrument, a Strad. So we went on to Stuttgart. The violin dealer said that the Germans, and therefore he, had been bombed by the Americans and he showed me charred pieces of great instruments that were in a big box that had been collected. I played the Stuttgart concert on my loaned Strad and we went back to Frankfurt. And, all of a sudden, my Guadagnini appeared. Many black marketeers were operating in downtown Frankfurt. I was told that a German man was walking with a little boy, carrying a violin case. A soldier went up to him and said, “You know I’m leaving back for the States and I don’t want to take my violin with me. What will you give me for it?” So he sold it to the German man and the German man had read the story about my stolen violin in the newspaper. He turned out to be honest and when he inquired, it was, in fact, my violin. He did get a reward for giving it back to me.

Italy

Following these German house concerts we had a month off and Lucy and I decided to drive to Italy. We rented a little Volkswagen Beetle. Rafe’s wife, Gerda, was Austrian and she told us that when we went through Austria we had to see Franz Josef’s glacier. On this trip, Lucy and I made a book. Wherever we visited, Lucy would paint a picture of the place and I would draw a picture of the place. We did go to Franz Josef Glacier and it was marvelous. We ate sausage and fried potatoes and walked on the glacier. It was on Grossglockner, which is Austria’s highest mountain, nearly 12,500 feet. We drove across Austria and went into Italy over Brenner Pass. We were having an argument—whether we should have brought two cameras and not just one so that we could have had one for black and white film and another for color film. I saw a truck in front of me driving very slowly and I decided to pass the truck. To my horror, it was a long truck and I saw he was turning left into a little side road. I had to make a quick decision—either slam on the brakes and maybe crash into him or go faster and escape him, which is what I did. The Beetle was small, and the truck’s tire fender caught the Beetle and literally threw us through the air. We flew into the field about 15 to 20 feet away, and landed on our tires. The cover in the back of the car, where the motor was located, had completely ripped off, the motor revealed, and all four tires completely burst. But we were alive and everything with us was safe, including my violin. The crash was so loud that the entire neighborhood, farming people, came out to see what had happened. The police arrived too. What a way for us to enter Italy.

Russia and Gerda

There were a number of difficulties surrounding Raphael Hillyer’s joining the Juilliard String Quartet. One of the foremost involved his wife, Gerda. She was a most sensitive and tough young woman who had fled the Nazis in Austria and arrived in America with her family. When Rafe joined the Juilliard String Quartet, the family had to relocate to New York and Gerda gave up her medical career that she had established in Massachusetts. I found her to be a wonderful and intelligent friend.

After a number of years, the quartet received an offer to make its first visit to Russia. Our first group discussion began in a context of excitement, but all of a sudden Hillyer said very quietly, “I am very sorry, but if the quartet must go, I will have to stay here because my wife is not well and I cannot leave her.” He continued, “However, if you must go, get another violist for the trip.” We were flabbergasted and I was in no doubt as to my answer. I told Hillyer, “We are a real quartet, and we go as we are now or we don’t go.” And that was the end of our meeting.

Two days later, when the four of us gathered together for a rehearsal, Hillyer said without preamble, “If the offer of a Russian tour is still on, I can go with one condition. I consulted Gerda’s doctor and he felt that if I took her with me on the trip, I could agree to go. It will not be easy, but I am eager to try.” The rest of us were grateful and the cultural affairs officer in Moscow was contacted.

Hard to believe, the quartet with Mrs. Hillyer arrived in Moscow. The cultural affairs officer plotted the scenario of the coming events with happy hopes. Even Gerda quietly smiled.

In Moscow we were invited to play for the students at the Moscow Conservatory, which was old and had a venerable history. I remember two things that happened at that visit. First we had tea in the director’s office. Then a quartet of young women, I think they were the Prokofiev Quartet, were brought in to perform for us in the director’s office. We were sitting there, and I remember they were offering Shostakovich and Gaydn (Haydn is Gaydn in Russia). We asked for Gaydn and they started to play Prokofiev. Their teacher shouted at them, “Your guests wanted your Gaydn not Prokofiev.” The other thing that happened was that a timid little man was allowed to come into the room. He was introduced and he handed us a program. What was the program? It was the great violin teacher, Galamian’s graduation program from the Moscow Conservatory—this man had been Galamian’s teacher.

The next day we took the train to Leningrad and by afternoon we were planning our schedule for the next day’s concert. We agreed to meet for lunch. Then, a strange moment occurred. Hillyer appeared at the restaurant without Gerda. Immediately we all asked, “Where is she?” He replied somewhat hesitantly, “Gerda has not felt well from the moment of landing in Moscow and finally when we arrived in Leningrad, she and I decided that she should fly to London and stay with friends while I finish the tour and then I will join her in London.” The three of us were surprised and thanked Hillyer for joining us on the tour. After a most successful concert in Leningrad the four of us flew to Odessa for our second concert.

That same afternoon, we were taken by our Russian hosts to many fascinating places, returning to the hotel late at night, happy, tired and looking forward to the next day’s concert. It was midnight. I was slowly calming down in a full tub of hot water in my little hotel room when the phone rang. Who in Odessa would be calling at midnight? I somehow got out of the tub, there was no bath towel, and rushed to the phone. I wrapped a window drape around me and asked, “Who is this?” The voice of the cultural affairs officer came through the phone static, “Robert, how is it going?” I thought to myself, he’s crazy. Why call me now? He continued, “Robert, are you still there?” I replied somewhat irritated, “Why call me this late?” Then slowly he went on, “Can you tell me if Hillyer’s wife’s first name is Gerda?” My heart sank, “Yes.” “Well, I’m sorry to tell you, we have just received word that she arrived in London, went to a hotel, and has fallen to her death.

The silence between us was endless. I finally cried, “My God!” How can I handle this? At least I began to speak and think, “Of course, the rest of the tour is out. We have to immediately get back to Moscow and then to London. When is the next flight from here?” He replied, “Again I’m sorry, but the earliest you can fly is at 11am tomorrow.” When the conversation ended, I was in a state of shock and realized that the next step was to tell Hillyer.

How? I knew he couldn’t move until the next morning. At this moment I made one of the worst decisions in my life. I would not tell him until the next day before we would leave on another sightseeing trip. In my room was a full bottle of whiskey. Between crying and swallowing, the longest possible night in my life ended at 6am when I found myself outside Hillyer’s door. Somehow, knocking, I entered and told him what had occurred. “What now?” When the group assembled and we finally found ourselves at the embassy, Hillyer must immediately fly to London. I elected to go with him. The other two Juilliard members remained in Mosow.

The trip to London with Hillyer was a long wave of silence and somehow we arrived for the funeral. It was after the cremation that Hillyer finally spoke quietly. “Let’s return to Moscow. I wish to finish our concerts in Gerda’s memory.” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I had also already spoken to Lucy in New York and she had gathered the Hillyer children together. When I told her of Hillyer’s intention, she emotionally called William Schuman, Juilliard’s president, who ordered the quartet back home without delay. No other instance in the fifty-one years of Juilliard Quartet life was so deeply wounding as the end of this wonderful, beautiful woman’s life. The radiant, shy touching smile of Gerda Sgalitzer Hillyer hides in the depth of my memories. I wish it to remain forever.

South America and Lucy

In the 1970s the Juilliard String Quartet was poised to begin an extended concert tour of South America. The first stop: Bogotá, Colombia. We had never before experienced the musical climate in this part of the world. Our first concert surprisingly was a stunning success. In the audience was a young, attractive woman, the curator of the famous Gold Museum. The following day was unscheduled and this curator invited us for a guided tour of her domain. As we walked the halls of the museum, Lucy could not wait to ask where she might find examples of the folk art of this region, not the commercial offerings found in airports and tourist centers. The curator was taken aback, “That is not my field of expertise,” she replied, “However, when we are finished here at the museum, if you cross the avenue behind the museum you will find an antique shop that may offer what you are interested in.”

The objects displayed in the Gold Museum were dramatic and astonishing but immediately afterward Lucy crossed the avenue with unstoppable determination. I meekly followed. The shop we entered was very quiet and the objects displayed were indeed breathtaking. The owner of the shop appeared. He was not a native Colombian but spoke English with a strong Hungarian accent. “What a wonderful concert you performed last night. I was especially moved by Beethoven’s quartet that ended with the formidable ‘Grosse Fugue.’” Lucy interrupted his praise to describe what she was looking for. The man became quietly thoughtful and ushered us into a spacious backroom containing various paintings, sculptures, ornaments and jewelry. From a far corner he retrieved a medium size canvas painting. At once we recognized that it was charming and offbeat. The painting contained the expected plaza and cathedral. However, what captured Lucy’s interest were two towering columns on each side of the church entrance. The columns were not of stone, but an amalgamation of birds. Tiny birds upon tiny birds rising endlessly into the sky above the church. Our music-loving proprietor hesitated then explained, “When Pizzaro came from Spain to this region in the sixteenth century, he brought many priests with him whose prime objective was to convert the ‘heathens’ to Christianity. One missionary priest lived for a time in a place now known as Cochabamba, Bolivia. In addition to his religious duties he taught a number of young men how to paint a picture. One particular youth possessed an arresting ability to create the picture you are now looking at.” Lucy was totally captivated. Out of her mouth sounded the words, “I love it, I want it and I must have it. How expensive is it?” The Hungarian modulated with utmost sympathy, “It truly is worth a lot of money, but I was moved by your husband’s music and your overwhelming desire. I can see how much the painting means to you. For that reason only, I will sell it to you for the amount I paid for it, US $800 dollars.” To us that was a lot of money but I could not keep Lucy from her newfound love.

Leaving Colombia, I triumphantly carried the painting along with my Stradivarius violin into the huge Braniff plane flying south to Santiago, Chile, where a number of concerts were scheduled. After landing, Lucy and I approached the customs counter with our luggage including my Strad and Lucy’s newly acquired painting. The situation in Chile at this time was dire: continuous street demonstrations, rioting with police and civilians literally battling for spaces between the buildings. Little did we anticipate what was to happen ten days later—the assassination of Chile’s President Salvador Allende.

In front of us stood a stiffly erect customs agent in a sparkling, fresh uniform. His handsome features and trim mustache were dominated by a stern facial expression. He ignored my violin case and our luggage. His English was curt and unfriendly. “You cannot bring this painting into the country.” No amount of entreaty prevailed. “Leave the painting here,” he demanded. “Take a receipt and when leaving Chile present your receipt. We will give back your painting.” What should we do? Leave the painting or cancel our concerts. Of course, play the concerts!

Minus Lucy’s painting we entered the country. Everywhere was chaos and tumult that played havoc with our nerves. Obviously the situation was deteriorating. It did not help to suspect that these happenings were being instigated with U.S. State Department help. We played our concerts and then we were back at the airport intending to fly to Buenos Aires, Argentina. We approached customs with our receipt. A soldier, uniformed, with a holstered gun asks, “Si?” We give him the receipt. His immediately replied in broken English, “Sorry, no painting here.” No amount of argument succeeds. Finally the soldier threatened, “Get on the plane. We will try to find your painting before your plane leaves.” Lucy was then assisted into the cabin of another Braniff plane nearly two stories high by two military policemen. Lucy sat in her seat distraught. Time was ticking and departure was imminent. Suddenly Lucy bolted upright into the aisle and before anyone could react, jumped out of the exit door and practically fell down the stairs attached to the plane. She rushed to the front of the plane and stood facing the front with hands outstretched, shouting, “I am not moving until I get my painting.”

Everyone on board was astonished—the pilots, the stewardesses, the passengers, and crew working on the runways. Even I, who have learned to expect almost anything from my beloved Lucia. Impasse? Forceful eviction? Not at all. In the distance on the edge of the runway, barely noticeable, was a man on a bicycle carrying a large, square package. As he neared the plane, Lucy saw that he was carrying her treasured painting. The man dismounted his bike and entered the cabin still carrying his unwieldy package, followed by Lucy. The tense moment relaxed. Breathing became normal. Lucy was not shot and we were soon soaring above the majestic peaks of the Andes on our way to Buenos Aires, our high spirits restored.

We arrived in the city where classical, western music is an important cultural activity. Even concerts by visiting string quartets are greatly appreciated. However, before our concert, we have the luxury of a free day, nothing scheduled. Lucy and I, happily hand in hand, wandered around the great open space in the center of the city, Plaza Major. The displays in the shops surrounding the plaza appeared wondrously inviting. Suddenly Lucy jerked my hand, “Look,” she cries. I dumbly follow her stare. In a little art shop below the store level we could not believe what we saw. She dragged me down steps to the shop. In the window were not one but two Cochabamba paintings exactly like ours—the columns of birds with the cathedral and all. Fantastic! How did the paintings get to this place? We hurried into the shop. Inside was a calm atmosphere and a single young lady, watching our tumultuous entrance. “Where, where, where did you get those two paintings in the window?” we simultaneously cried. “What?” she responded in English. “Those two paintings? Oh yes, you mean the Bolivian Indian paintings.” She smiled a warm, friendly smile. “You are interested, no?” We pleaded, “Please, how did you obtain them?” She laughed disarmingly and proceeds, “It is quite a story.” She appeared somewhat nervous but continued, “There are two brothers who live in Cochabamba, Bolivia. They are very talented and every year they send us a few of their paintings.” Lucy was confused by the use of the present tense. “They send you these paintings now?” The girl answered, “Of course. They have been doing this for years.” I blurted out, “How much do you sell them for?” She says disarmingly, “They are not very expensive, about $150 each.” Lucy gasped, “Are these brothers still living?” She responds, “Oh, very much so. We hope they continue a long time because their work is very popular.”

Lucy turns to me and orders, “back to the hotel.” When my wife orders, I do not resist. In our hotel room we were silent. Lucy did not take off her coat, deliberately picking up the telephone she dialed a New York phone number, her bank. With hardly an opening sentence she inquired, “Has an $800 check made out in Bogotá, Colombia, been cashed?” She was told no. She answers, “Good and cancel the check right away.” At last we were saved. The deceptive Hungarian émigré in Colombia would not get away with this fraudulent enrichment.

Lucy and Eleanor Adam shopping for artwork on a tour

Finally, this long, exhausting South American tour is finished and we unpack our bags in our New York apartment. In the following days our collective guilt about keeping the “criminal” painting grows. A friend, the pianist Horatio Gutierrez is about to embark on his foray into the southern hemisphere. We ask him if he will be playing in Bogotá and he is. We tell him that we wish him to return a painting to a shop owner in Bogotá and he agrees. Later, there remains a nagging and somewhat haunting shadow. Lucy and I both agree, it was a refreshing painting and we miss it.

Aspen, Colorado

In 1949, a very unusual man, Walter Paepcke, was responsible for the revival of a ghost town named Aspen. At that time, there was nothing there except for mines and old miners. The mines were defunct and no one was mining anymore. He started to bring people to visit. He brought Albert Schweitzer, the Nobel prize winning philosopher physician from Africa. He brought Mitropoulos, the internationally famous conductor and composer, and the Minneapolis Orchestra to come and play. And, they celebrated the great human writer, Goethe, on a centennial of his birthday.

So, the Juilliard String Quartet was practicing in our Juilliard studio and the door opened, as it did on many occasions. And this time it was a fellow, he looked like a businessman, and he asked us, “What are you doing this summer?” We told him that we hadn’t made plans yet. He said, “I’m Walter Paepcke and you might have heard about the music festival that I started in 1949. It isn’t just music but a mixture of the arts including playwrights, philosophers and everything. It is an institute. And, we are going to continue it. I have plans for the future and have already asked the Paginini Quartet to return for five weeks. I’d like for you to also come for five weeks and dovetail so that you can play the Mendelssohn Octet and the two Darius Milhaud quartets that are supposed to be played separately and together. Would you come?”

Walter Paepcke, Founder of Aspen Institute

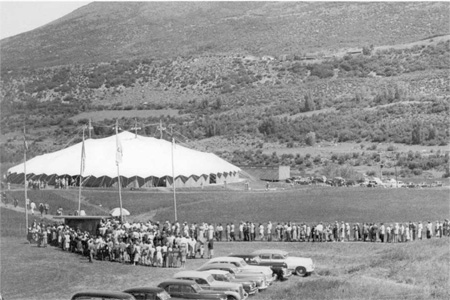

Aspen Music Festival tent, early days

We accepted Mr. Paepcke’s invitation and that began our connection to the Aspen scene. Lucy and I drove my Jeep station wagon and we had a little shack at the top of Red Mountain. Vronsky and Babin were there. They were a famous piano team and Babin started the Cleveland Conservatory. Thornton Wilder who wrote Our Town was there and so was Isaac Stern. We had an absolutely wonderful time. One night for fun we played all six Mozart viola quintets with the wonderful violist William Primrose.

Another time, Jennie Tourel, the wonderful mezzo-soprano, was there singing and we had our four-year-old daughter Lisa with us at the concert. We always sat in the top row of the open air tent where all the concerts were played, so we could leave easily in case Lisa got noisy. Lisa was in dress up clothes and high heel shoes and we went backstage. All of sudden Lisa went over on her own to Jennie Tourel and started pulling on her dress. Jennie was annoyed but Lisa continued. Finally Jennie turned around and said, “And little girl, who are you?” Lisa looked at her and replied, “I am Jennie Tourel.” From that moment on, they were fast friends.

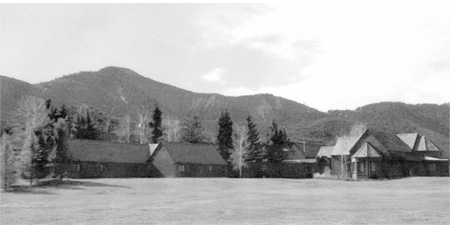

St. Benedict’s monastery, Aspen

We spent many wonderful summers in Aspen. I had my mountains and I hiked all over. We also went and played at the monastery at Aspen every summer, where we made deep friendships. When we first visited the monastery all the monks except Peter, who was in the gift shop, had taken a vow of silence. Through Peter we offered to bring music to the monastery since they could not accept our invitation to attend a concert at the Aspen Music Festival tent. They were thrilled, and we brought the first music concert to be played in that remarkable place. Over the years we became friends with several of the monks, Father Joseph, Brother Benedict (who made wonderful sculptures out of nails and bolts and later became a dentist!), and Brother Peter. The monastery has a special place in the heart of our family.

Jennie Tourel, mezzo soprano

We also became connected to the Aspen Institute, which is dedicated to intellectual exploration and dialogue of all kinds. Leaders in all different fields come to give lectures and participate in seminars. Lucy and I both participated and I would give lectures. We were very close to Joseph Slater, the man who ran the Aspen Institute from 1969-86. Slater was a passionate lover of music. One time he asked me, “Bobby, give me a one sentence definition of a true musician, a really great musician.” I thought a moment and finally said, “The simplest thing I can say is a really great musician is someone who knows how to connect two tones.” Joseph Slater said, “That’s interesting that you say that because that is exactly what Isaac Stern told me, too.”

Robert and Nicholas playing for an Aspen Institute Seminar

That is what Bartók and Hindemith used to say about great pianism, or producing great tones on the piano. Hindemith said, “It is of no importance whether a single tone is produced by Franz Liszt or by Mr. Smith’s umbrella. A single tone, as we have stated repeatedly, has no musical significance, and the keyboard does not provide any exception to this rule. The tones released by the keyboard receive musical value only if brought into temporal and spatial relations with each other. Then the infinitely subtle gradation in the application of pressure, the never-ceasing interplay of minutest dynamic hues and temporal length proportions, all the bewitching attractions of good piano playing—only the artist can produce them convincingly; and it certainly is not his hand that reigns within the microcosm of musical diversity but his musical intellect as the master of his playing hand. Even the application of the world’s most perfect umbrellas could never cope with this diversity, gradation, and interplay.”7

Bartók used to say the same thing about the connection between notes.**

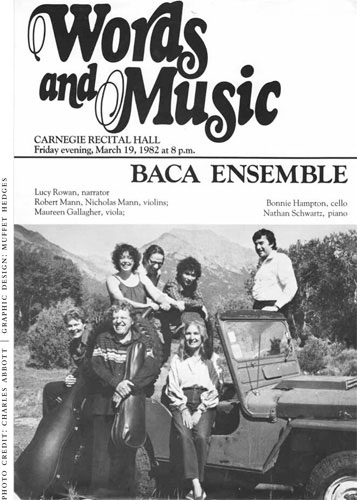

BACA Ensemble flyer, 1982

Years later, Slater came to me and said, “You know, I’m setting up in another place in Baca, Colorado, a similar thing to the Aspen Institute. It will be an extension, but I want to add a music program. I just can’t have it without a music program.” We suggested that we form a group, using myself, my son Nicholas, Lucy narrating, and in addition a violist, cellist and pianist (our dear friends Bonnie Hampton and Nathan Schwartz). He liked the idea and we succeeded. The group was called the Baca Ensemble, and for about six glorious summers we lived up in the mountains (nestled under the Sangre de Cristo range), in the middle of nowhere. Total freedom to prepare two concerts a week for the participants at this program, with repertoire of our choice. It couldn’t have been a more wonderful experience.

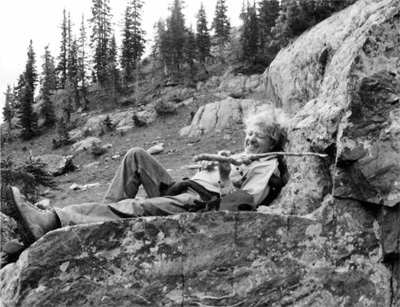

Playing in the Aspen mountains, later years