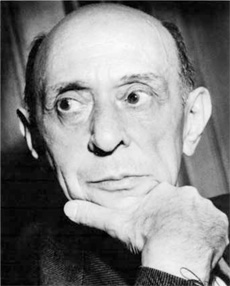

Arnold Schoenberg

It was 1947 and the quartet had just started. Because of our connection to Eugene Lehner, we loved the music of Arnold Schoenberg, who was living in California. I also was a composer. So, on a trip to Glacier, lasting about two weeks, I took along my camping equipment and my own compositions, leaving them at a place along the way. When I left Glacier, I flew from a city near Glacier Park, through Reno, Nevada, and down to Los Angeles, where my family was now living. My brother lived in Los Angeles, and my quartet had given me the task of contacting Schoenberg. We knew that he had composed four string quartets and we wanted to know if he would write a fifth quartet for the Juilliard String Quartet.

Dimitri Mitropoulos, a friend of mine and of the Juilliard String Quartet, was the great conductor, pianist and composer. He told us that he would help to pay for a fifth Schoenberg string quartet. We thought that we could raise about a thousand dollars for the commission. I arrived in Los Angeles and I called Arnold Schoenberg and he agreed to see me. I went to his home in Westwood and as I remember it, I brought along five or six of my own compositions. I asked if he would take a look at them, and he did. We sat on the same sofa and he didn’t look at the score very carefully. He just sort of turned the pages to see what I had written. And then he said, “Young man, if you want to be a composer, I give you only one piece of advice. Whether you like it or not, whether you are sick or not, no matter what, you must write at least fifty bars of music every day. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad. If you do this every day long enough, you will be a composer.”

Then I came to the point to ask what I needed to. I said, “You know, Mr. Schoenberg, I started the Juilliard String Quartet and we are a young quartet. We really love your music enormously. Would it be possible, if we can raise the money, to commission a fifth quartet?” I remember during this conversation that Schoenberg had very bad eyesight. However, he was still composing. He showed me in his bedroom that he had a wall where he had composed a big work on the wall. He was composing on the wall because his eyesight was so bad. He told me that he hated to compose now and would put off his composing until it was almost upon him. Then like torture, he would start composing and get into it and write quickly and be done with it. He was that kind of a genius.

I also remember that Kolisch, the violinist who had been so involved in publicizing the original metronome markings in Beethoven scores, was walking in and out. At one point, Kolisch took me aside and he whispered to me, “Well, how much money would you think the Juilliard String Quartet could give for a commission?” I was embarrassed because I didn’t think we had enough money and we didn’t. I told Kolisch that Mitropoulos would help us out with one thousand dollars. This was a lot of money for us. After all, we were each only receiving $2,500 for the entire year. Kolisch said, “Mr. Schoenberg could not do that for such a small amount. Really, don’t even bother asking him anymore. He needs much more money than that.” He was right of course and we didn’t have the money. That was the end of the Juilliard String Quartet’s attempt to commission a Schoenberg Fifth String Quartet.

Arnold Schoenberg

However, this did set the ground for something that happened a few years later, I think in 1950, our third summer as a quartet, right before Schoenberg died. We got in touch with him again and asked if we could play his quartets for him. We were invited to his house to play. There were many people in attendance that night, including the composer David Diamond who took notes, though I didn’t know him at the time. I remember that Schoenberg’s daughter Nuria was there. We told him that we would like to play the first, third and fourth quartets for him. We didn’t play the second quartet because it involves a singer. We were confident about playing the quartets because Eugene Lehner had coached us on the Schoenberg quartets. We had played for Edward Stuermann, who was one of Schoenberg’s close colleagues, and I think we even played one of the quartets for Kolisch. We asked Schoenberg which quartet he wanted to hear first. I remember that he was a small man, with a humorous smile. He told us in a raspy voice, “The first quartet. I haven’t heard the first quartet in a long time. Please play that.”

The first quartet of Schoenberg is in four movements lasting 45 to 50 minutes without a pause, depending on your tempi. When we finished it, I said, “You know Mr. Schoenberg, the people who were playing Beethoven for Beethoven could have the response of Beethoven. We can’t do that. But now we have the chance to find out what Arnold Schoenberg thinks of the way we play his string quartets.” Schoenberg was quiet for a long time and then he started chuckling. He said, “You know, you played this quartet in a way that I never imagined it.” We thought, My God, what have we done wrong? So I said, “Well, Mr. Schoenberg, please don’t spare our feelings. Tell us how we should go about playing the quartet the way you like it.” He didn’t say anything for some time and then he said, “No, I like the way you play it. I want you to continue to play it this way.” And that was that8.

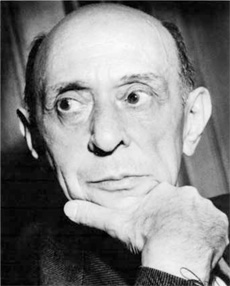

Elliott Carter

(written as the preface to the score for the complete Carter String Quartets, at the request of Elliott Carter)

Two violins, a viola and a cello. What is it about this non-exotic string foursome encompassing the range of the human voice that for more than 250 years has motivated composers to create such a compelling repertoire? The pantheon of great string quartet literature is illuminated with inspirations from Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert on through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the present.

After a lifelong involvement with this repertoire, I cannot escape the conclusion that Elliott Carter in his five quartets has created a musical world that, for its boldness of design, integrity of form, polyphonic interplay of voices, virtuosic use of instruments and profound emotional expressiveness, is as fulfilling as any in the entire string quartet literature.

Juilliard String Quartet with Elliott Carter

My experiences with Carter’s quartets parallel my earlier encounters with the late quartets of Beethoven. Some critics may question the validity of Carter’s tonal language, just as many nineteenth-century critics questioned the language of Beethoven’s last quartets. Although my musical ear had already expanded through diligent study of Bartók and Schoenberg, I could not believe what my ears took in on hearing Carter’s First Quartet (1951). Here was a soaring musical spirit anchored in a traditional path but bristling with amazing new colors, vital and mysteriously shifting rhythmic pulses, emotional highs and lows that transported me for over 40 minutes. I knew then that I must play this man’s compositions.

I vividly remember the Juilliard String Quartet’s struggle to play the notes contained in all the passages, to feel naturally the startling rhythmic modulations—like shifting gears—and the struggle to hear as well as comprehend the quick-passing vertical sonorities. When rehearsing late Beethoven quartets, string ensembles are astonished at the clash of non-related notes in many passages when played in slow motion. But like distance in viewing a painting, such detailed aural confusions become magically clear when played at the proper tempo. This is also true for much of Carter’s polyphonic writing.

Carter’s Second Quartet, first composed in 1959 (later revised), was not premiered for some time, and finally the Juilliard was given permission to play the first performance. In this work was a truly new scoring for string quartet. The four voices were isolated not only by a singular character and tonal base for each instrument, but also by physical space. The tonal and rhythmic dimensions of this music were powerfully concentrated, and the discourse between instruments even more liberating and evocative than in the First Quartet. A sure test of the value of this music lies in the hundreds of hours required to overcome its difficulties. I’ve never begrudged that time working on Carter. The rewards became more and more satisfying with each new performance. It is important to acknowledge here that complexity in music is not in itself good or bad. Only when such unusual relationships of vertical sounds combine with linear motion to forge a strong musical effect can one appreciate the value of that complexity.

While the challenges of learning the first two Quartets were extraordinary, the difficulties in preparing the Third Quartet (1971) were monumental. Again there were new rhythmic relationships to master, but additionally there was a whole new domain of instrumental coordination. The Third Quartet is in reality two duos, one of violin and cello, the other, violin and viola. I chose to play “Duo II” with the viola. Earl Carlyss, our second violinist, played a part in “Duo I” that explodes with all kinds of pizzicato derring-do. He is probably the only violinist who has ever practiced scales and arpeggios pizzicato (no bow) to develop his technique for the Third Quartet. It took the Juilliard String Quartet two full rehearsals just to be able to get through the first measure of the piece. In this measure “Duo II’ has the violin playing six triplet beats that can be divided into two or three larger pulses. The violist relates to three of those pulses with groups of five notes in each pulse. “Duo I,” while harmonically connected to “Duo II,” relates only to a four-beat pulse that coincides with “Duo II” at the end of the bar, a bar that lasts just under three and a half seconds.

PHOTO CREDITS: E. CARTER/KATHY CHAPMAN, R. MANN/CHARLES ABBOTT

Publicity, concert at Merkin Hall, New York City

Complicated? Yes, but when negotiated successfully, the sensation is similar to catapulting over a roaring waterfall at the start of a white-water journey. I believe that performances of this work have resulted in some of the exhilarating moments of my life. There is a timekeeping device called a click track that can be a great aid in ensuring the accuracy of the performance, but somehow the Juilliard String Quartet always preferred to take its chances without it.

I first heard the Fourth Quartet (1986) played by the Composers String Quartet. Here again was a new lyricism, fascinating colors, and an almost Mozartean transparency. I couldn’t wait to begin work on this piece. What I was not prepared for was the skill with which Carter wove together the individual textures and rhythmic figures. While he had separated the tonal and emotional character of each instrument in the first three quartets, he now assigned a unique rhythmic character to each of the four voices (violin I, “the square;” violin II, “master of triplets;” viola, “external fives;” cello, “tormented sevens”). The miracle is that this exotic aural kaleidoscope produced a coherent, powerful musical statement.

I would like to share with the reader one personal observation. In earlier days, it seemed that Elliott Carter’s major focus was on the hierarchical rhythmic realization of the performance. Many years later there was no question that the composer’s ultimate desire was for an interpretation replete with expressive, surging intensity.

Is there no end to this man’s creativity? Of course not! A stream of arresting new works flowed from his pen until his passing, and the Fifth Quartet (1995) is among them. Like the previous quartets, I find the Fifth Quartet ever fresh and open-ended. I first heard it played by the Arditti Quartet. In 331 measures of music, more than a third of these are scored for only one or two parts. Here we see the need to communicate with a more inner-orientated voice, as with Beethoven, Bartók, and Shostakovich in their last quartets. Structural and emotional continuity is simplified. Six contrasting movements are connected by five interludes, where four voices speak to and with each other as in a recitative.

The Adagio sereno obtains a heavenly musical purchase by the ingenious use of harmonics. And the final three and one half measures achieve a ludus tonalis signature that brings the Fifth Quartet to a perfect, cadential end. I confess, as a long-time string quartet addict, that performing this brief denouement with the other three players—expiring after a last double-stop ends, sotto voce—alone provides me with the answer to why string quartets are still written after 250 years.

I know that the five works will be ever present wherever music is important. I am grateful to have experienced them and to have known Elliott Carter, just as in an earlier time Ignaz Schuppanzigh knew Ludwig van Beethoven.

Aaron Copland and Lukas Foss

We also played with, and loved being with, Aaron Copland. He was one of America’s best composers and was also a magnificent human being. He was warm, supportive, and vulnerable, and we had the greatest time with him. When he played piano, he would always get very nervous in performance. We recorded the sextet (the famous clarinet, piano and string quartet piece) and the piano quartet. Once Copland called me and said, “Bobby do you know a good violinist who could make a transcription of my duo for flute and piano for violin and piano.” I said, “I certainly do, me!” So Copland came over and gave me the music and told me what he had in mind. I transcribed it and he accepted everything that I did. I think he changed one spot where I’d gone an octave higher. He liked the lower register and lowered it.

Another pianist/composer we played with was Lukas Foss. We had a wonderful time with Lukas at the Library of Congress where we played both Mozart piano quartets.

Béla Bartók and Peter Bartók

I have to say, one of my great regrets is that I never met Béla Bartók. He was busy at Columbia during the time I was at Juilliard in graduate school. He was working on all of his recordings of the folk music that he collected on his field trips. He had the music on all of these old Edisons. He was busy transcribing them onto more contemporary equipment. I loved Bartók’s music and was trying like mad to learn some of the quartets. I was too intimidated to try to get in touch with him in hopes of playing for him. He was known to be not too impressed with performances of his music. Once, two sisters played the First Sonata for him on piano. They were expecting a great deal of help from him after he heard them, and he all he said was, “You know, the first movement was a little too slow. The second movement was too fast and you have to practice more.” Bartók also didn’t believe in teaching composition. And yet there is a wonderful book written in which people who studied with him write their memories about him. It really is quite illuminating.

I did learn something firsthand about Bartók from a young composer from Hawaii that I knew at Juilliard by the name of Dae Kom Lee. Somehow, he wrangled a session with Bartók. He went over to Columbia to show Bartók his compositions. Dae Kom told me that Bartók looked at his music and then asked him, “Do you ever play Beethoven piano sonatas?” He answered, “Of course I do.” Bartók answered, “Well, I want to show you something.” He took one of Beethoven’s most cryptic scherzos, minuets or whatever. Dae Kom told me that they spent three hours dissecting it with Bartók showing how he thought Beethoven put it together. That was Dae Kom’s lesson with Bartók.

When Peter Bartók, Béla Bartók’s son, lived in New York we became very good friends. During the recordings of Bartók’s music that Peter produced, he would ask me to look at the music and to make a decision to put a flat or sharp in a particular spot where there was a debate because there were different versions in Bartók’s handwriting. Peter had trouble deciding which version to use and would ask me for help.

Béla Bartók wasn’t making any money with his compositions and he was very ill while living in America. He spent some time at Black Mountain College in North Carolina where there was an ex-Hungarian community. One of the people who lived there was an international copyright lawyer by the name of Victor Bator.

Bator convinced Bartók, who was on his death bed, that Admiral Miklós Horthy was in league with the Nazis and had taken over Hungary. Of course Bartók hated the Nazis and fascism. Bator said, “You know your will is such that if you die probably a lot of things that you want to give your wife or your son or to this or that will end up in Horthy’s regime’s control. So I want you to make a new will.” So Bartók made a new will and named Bator to be its executor, the head of the trust. The will was worded the way that Bator told him to word it. After Bartók died, it turned out that Bator really had used his role as executor to get all of Bartók’s manuscripts, and correspondence given to the Bartók estate, not the family members. This meant that family members received no money from the sales of his work. When Bela Bartók was alive he didn’t receive much income for the performances of his pieces. After he died, however, they generated more and more money.

Peter Bartók was a fantastic recording engineer. In the early days, he only worked in monaural. However, people claim that the sound he got was one of the most wonderful sounds that anybody ever recorded. Peter had a company, and Béla Bartók put in his will that the estate should help Peter to keep the recording company going and, of course, one of the major missions was to record all of Bartók’s works. And, Bator was doing this.

Bator was also doing many things that were not helpful to Peter and they started a long lawsuit that lasted for many years. Peter’s mother, who was Bartók’s second wife, was a little unstable and she had gone back to Hungary. Bator would give her money so she wouldn’t support Peter in the lawsuit. It was a terrible situation. Peter was getting into thousands of dollars of debt to pay the lawyers. By now Bator was a communist. He would go to the American court and say, “if you give a ruling and take this away from me it’s going to be against the communist government in Hungary.” Peter was losing all of the battles. Finally, long after Bartók died, Peter finally won and got all of his father’s manuscripts. Letters too. Finally, he got everything and had control.

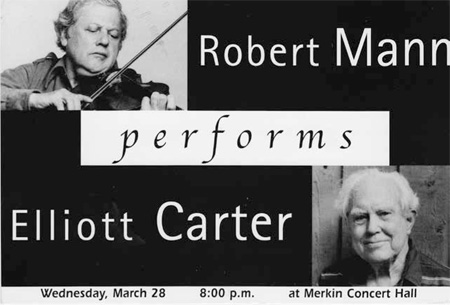

In any event, we were very good friends and Peter had an idea. He wanted to record his father’s violin and piano sonatas; his father had given him the privilege of being the first to record the first piano concerto. Peter asked me to record the solo sonata for him. He asked me, “Do you have a copy of that score? If you don’t we will have to get you one. I’m going to give you the original. I’ve transferred it but the original is nice to have.” I have to say that I am not a great violinist. I’m not being overly humble. But that was the best that I have ever played in my life. Joseph Szigeti wrote to me saying how tremendously impressed he was with the recording. I treasure that.

We also did the first recording of the first violin and piano sonata. We followed that recording with the second violin and piano sonata, and by that time Peter was recording in stereo. Peter wanted to have the piano concerto recorded and he asked Lee Hambro to play it. He said to me, “Bobby, you and Lee are such great friends and I need a conductor and you’re a conductor so I want you to conduct.”

Szigeti letter to Robert

I loved, loved this idea. Peter had a very unusual arrangement. There was a cellist in the Boston Symphony, Josef Zimbler. who played with a group in the summer that he called the Zimbler String Sinfonietta. It was made up of musicians from the Boston Symphony who he paid to play concerts when they weren’t playing in the Symphony. So, Peter had the Zimbler Sinfonietta hired for the recording. When Bator heard about this he said, “Absolutely not. Robert Mann. Who ever heard of Robert Mann as a conductor?” Bator went to his Hungarian friends, such as Fritz Reiner and Eugene Ormandy, who were all busy. Bator said that he would have Lee Hambro as the pianist. That was okay. But, for the conductor he said, “I want Tibor Serly.” Tibor Serly was a fairly decent composer and musician who tried to be close to Bartók during his last days. So Bator felt that he was the right person to conduct since he understood Bartók very well.

The story continues. I wasn’t there. I heard it from Eugene Lehner who was in the orchestra and from Leonid Hambro. Eugene and Lee went up to Boston for three recording sessions, and I was in New York. I got a call from Peter Bartók who said, “It’s a disaster. We haven’t got a recording.” You know, recording, especially with an orchestra, is very expensive. You record for 45 minutes and then you take 15 minutes off. I learned later that Serly got in front of the Boston Symphony and talked for most of the 45 minutes. He told the orchestra what a difficult piece it was and how he’s the only person that understood the music. He wanted to impress the orchestra, and went on and on.

So Peter asked me to visit him at his home in Riverdale to listen to the recording. Sure enough it was very sloppy. None of the tempi were any of the tempi that Bartók suggested on the parts. I said, “Well, I don’t know what you can do. That’s it.” I got a call from Victor Bator who says, “I want to see you.”

I went to see Bator and in his office he told me that they had already spent $9,000 (which was an enormous sum of money in those days) and the recording was way over budget. He said, “What we would like you to do is to listen very carefully to the tapes, and those places that are the worst, I want you to go up to Boston and have a session with the Boston Symphony members and re-record those spots so that we can make the splices.” I said, “Excuse me, but I’m not going to do that. I’m sorry, Mr. Bator. That’s not my interest and I don’t want to do that.” Then I left. A week later he called me back. He said, “First of all I have to tell you. I asked Fritz Reiner, Joseph Szigeti, and Yehudi Menuhin, what kind of a conductor you are. They all said that they didn’t know, but they did know that you are a fine musician. They also all agreed that you could do it and that I could trust that you would get the record done. So, will you go up to Boston now? I’ll give you two sessions, and record it.” I was now in a bargaining position. I told Bator that I couldn’t do that. I told him that he would have to postpone the recording for at least a month so that I would have time to study the score. I also would have to have his guarantee that if I needed a third session that he would give it to me.

So, I went to work and learned the entire orchestral score, one of the few orchestral scores that I memorized every note of. I went even farther. I got all of the parts and I remarked them. Everyone argues about what’s written in the score. I had heard a lot of Bartók and I knew that the orchestra, for instance, wasn’t making certain kinds of accents that Bartók wanted. The notes were either too short or too long. So I marked all of the parts. I also went to see my conductor friends, such as Jorge Mester. I asked him, “What should I do?” I told him what I was doing to prepare and wanted him to tell me what else I needed to do.

Finally, before I went to Boston, I talked to my friend Leon Barzin, who had been Toscanini’s assistant. Leon was a very talented, marvelous conductor who really should have had much more recognition for what he did. He led the National Orchestral Association, which was a training orchestra for really marvelous young professionals who hadn’t found jobs yet. I asked Leon if he could give me half a rehearsal to conduct this group to try out my conducting skills and to hear how the music that I had re-marked sounded. Lee went with me and we were given an hour and then it was time for a break. I got ready to leave and I thanked Leon and said, “This was just wonderful. I really learned a lot.” Leon wanted to talk to me and he called me into his little Green Room. Then he blasted me, “Why? You’re stupid. Why did you do this? Why did you do that?” He gave me hell and pointed out many places where he thought I had gotten it wrong. I told him thank you and got ready to leave again. He said, “Oh, no, no, no, no. I’ve decided that you should take the rest of the rehearsal. I want to see if you understand what I’m telling you.” He was that kind of a guy. So I finished the rehearsal.

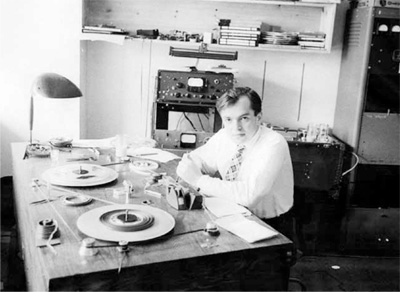

Peter Bartók in his recording studio

I went up to Boston and I took Rafe Hillyer, and also Jorge Mester. Rafe and I had gone through the score together. When we got to Boston to do the recording, Peter told me that there wasn’t a place on stage where he could put his equipment. The orchestra was on the stage of Boston’s Symphony Hall, not set up like they would be playing a concert but sitting in a rectangle. The Boston Symphony members that I was going to conduct knew me from Tanglewood as a violinist and a quartet member. So when they saw me coming to conduct them, they thought, “Oh God, we have another amateur. We’ve already had an awful experience recording this piece.” The first thing that I did when I got to the podium was to ask them to put my music stand away. I knew the score by heart and didn’t need a score in front of me. I told the orchestra, “Now listen, you don’t know me as a conductor. I’ve listened to the tapes and you know that they are really terrible. I really know what to do. I want to rehearse certain sections.” So we started right off with the first movement. Within five minutes they knew that I not only was a good conductor, but that I knew what I was doing with the piece. I had Rafe and Jorge, who were in the recording room with Peter, alerted to what I wanted to accomplish. So we wouldn’t waste time, I would say over the microphone, “Have I got what I talked about, or do we need to do it again?” They would answer yes or no. We recorded it in two days and the results were phenomenal.

When I went up to the recording booth, I was still holding my batons. Rafe looked morose and said, “I suppose we have to start looking for a new first fiddler for the Juilliard Quartet.” And what I did was to break the batons and throw them out a window.

By the way, the sound Peter achieved in his recordings, acoustically, was very strange but fantastic. When I recorded the Contrasts with Stanley Drucker and Lee Hambro at Washington Irving High School downtown, he didn’t have us on the stage but had us take our seats on the floor of the auditorium. And, when I recorded the solo sonata at the Pequod Library in Connecticut near Bridgeport, he would turn some seats over so that the wood was there and on other seats would leave the cushions on top of the seats. He was always listening to the sound.

Columbia Records

The Juilliard String Quartet had a recording relationship throughout our years with Columbia Records. The first great quartet to record with Columbia was the Budapest Quartet. So, in the early years the Juilliard String Quartet could only record those pieces that the Budapest would let us record. After all, the Budapest Quartet was the top dog. They weren’t going to play Berg, so we recorded Berg. Goddard Lieberson, who was the president at Columbia Records, was very interested in American music, and so we also recorded all kinds of American composers. Much later, after Lieberson resigned from Columbia, we were asked to record the two Charles Ives quartets. At that moment, it wasn’t the time for us to make a recording of Ives quartets. It wasn’t that we didn’t want to, but we had other things on our mind. Columbia came back to us and said that they needed to have those quartets recorded. We made a counter suggestion. We proposed if we were to record the two Ives quartets, would they let us re-record the Schoenberg quartets? We had recorded them much earlier in our career.

Lieberson had agreed and then left Columbia. We were told by Columbia that they would not agree to the arrangement and that it had all been Lieberson. Now he was gone and they wouldn’t do it. I was very upset and at Lucy’s suggestion, I called his son, the composer Peter Lieberson. I was sort of embarrassed, but I pleaded with him. I said, “Even though your father no longer works at Columbia, could you ask him to help us and to tell Columbia to honor their promise for us to record? He’s a respected man.” Peter’s first response was no, “Don’t lay it on me, Bobby.” However, he finally did it. He went to his father and his father spoke to Columbia. And, very begrudgingly, Columbia allowed us to record the Schoenberg quartets again. For some absolutely weird reason, those Schoenberg quartets won the Grammy Award for chamber music that year. That usually doesn’t happen, and the Grammy tends to be given to something more popular, like Perlman playing a Brahms trio or something. It was unbelievable.

We recorded about 150 pieces of music. I can’t remember half of the recordings we made. We recorded many little weird works such as a little cantata by Milhaud, narrated by Madame Milhaud, as well as a sextet by Ellis Kohs, both for Columbia. I also remember that on our first trip to Europe, we recorded an early string quartet by Irving Fine, and a twelve-tone Norwegian composer. We recorded and performed in Oslo. That actually was one of the ways we were able to go to Europe that first time, by agreeing to record the Norwegian composer.

One time, Columbia Records wanted us to record Shubert’s Trout Quintet, one of the greatest pieces of all time. They wanted us to use the pianist Murray Perahia and he refused to record with us. He said that the Juilliard String Quartet changes tempo when they play, for example, a melodic tune. In other words, he was saying that we, the Juilliards, didn’t keep the tempo going from beginning to end. Well, we did admit that this was true.

Later we did play the Trout Quintet with Claudio Arrau at the Library of Congress. We also played the Franck and Dvořák quintets with him. He would never allow us to skip one repeat. He said every repeat was sacred. Once, when we were taking a break in a rehearsal at the Library of Congress in Coolidge Auditorium, we were sitting where the audience sits, just resting and talking to him. One of us asked him, “Claudio, why don’t you ever play any contemporary music?” He answered that he just didn’t feel comfortable playing music by contemporary composers. He said, “I’ll show you.” He got up on the stage and he played a Stockhausen piece from memory, about 21 minutes, and it was fantastic. When he was finished he came down and said, “You see, I don’t really feel this music.” But he was capable. He preferred to play contemporary music only at home for his own interest and curiosity.

And later, we played the Trout Quintet with a Naumburg winner, the Cuban-born American pianist Jorge Bolet. Bolet was a marvelous gentleman and a fantastic pianist who learned in a very interesting fashion.

We were scheduled to play our first performance with Bolet in London. Then we were going to play at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., followed by a performance in Alice Tully Hall. We had three performances scheduled. When he arrived in London to rehearse with us, it wasn’t that he hadn’t practiced the piece but he was completely ill at ease playing it. His genius was that after three rehearsals he played it beautifully. By the time we got to the Library of Congress, it was magnificent and by the time we played at Alice Tully Hall, I just wish that we had recorded that performance. It was one of the great performances of my life. It was fantastic.

Glenn Gould

We played with Glenn Gould, who we met through a Montreal-based critic friend of his. Glenn, of course, lived in Toronto. I don’t know how Columbia got us together but the first thing we ever played with him was the Schoenberg Ode to Napoleon for narrator, piano and string quartet. He brought an actor friend of his down from Canada. The recording sessions were fascinating. He tried to show his actor friend how to do the narrations. I thought Glenn Gould was better than the actor friend. I remember whenever we took a break he would immediately start playing his own arrangements of Richard Strauss operas. He knew every note that Richard Strauss wrote and he would play and sing. He would say, “Now, here’s this phrase from this opera, this act.” He was just amazing.

The next recording we played with Glenn Gould was a Christmas record, for which he’d written a funny little oratorio. I can’t remember the name of it but it involved a string quartet. He wanted very much for us to play it. He’d also written a long, serious string quartet that sounded a little like the composer Franck’s language. In fact, he came to Bobby Koff’s apartment to show us his piece. It was late at night and he was playing and singing his quartet very loudly and all of a sudden there was a knock on the door and a policeman was there and said, “You’d better stop this yakking or else we’re going to have to do something about it.”

We were happy with Glenn on most occasions when we were together. Columbia came to us again and said, “We want to put out an album of all Schumann. We want his three string quartets and you already played the quintet with Leonard Bernstein.” Of course we wanted to do it. They asked, “Would you record the piano quartet with Glenn Gould?” Yes of course, that would be wonderful.

We arranged one rehearsal with Glenn during which the sound engineers would set up. By the second rehearsal they wanted to start recording. We didn’t have a performance plan. Glenn was coming from Toronto by train; he never flew. He met us at the old Columbia recording studio which was located on the East Side. When he arrived, the first thing he said to us after we greeted each other was, “I hate the music of Robert Schumann.” We started laughing and said, “Glenn, why are you doing this then?” His answer was, “Well, it’s a challenge. We’ll try to figure out a way to make it work.”

He was very perverse. Where the score said legato, he played staccato; where it said crescendo he would make a diminuendo. I remember at one point, the scherzo has very quick eighth notes which are marked pianissimo, as soft as possible. Glenn said, “I am not going to play it that way. The recording equipment is perfect and I want to play it the way I play it. The sound engineers can bring the sound down in the control room. They can bring it down to pianissimo.

Glenn had great faith in technology. I remember another incident when we were listening in the recording room as a group and the telephone rang for Glenn. It was Jamie Laredo and they agreed to record all the Bach works for violin and clavier, also for Columbia. They were talking about arranging rehearsals and it seemed that whenever one was free the other was busy. We were listening to the entire conversation only hearing Glenn’s side. Finally we hear Glenn say, “Well I have a suggestion—we really can do this. We will both get a room that has an amplifier for connections to telephone wires and I will play in Toronto with the piano and we can rehearse by telephone.

The Juilliard String Quartet was at Aspen when Columbia sent us the recording for our approval. We were outraged. Even though we loved Glenn Gould and it was fantastic playing, we thought that in the slow movement instead of hearing the beautiful cello solo all we heard was the boom boom boom on the piano. So, it was my job to call the head of Columbia Records’ classical division and tell him that they couldn’t release the record. He said, “Now look, I’m going to speak to you in terms you have to accept. First, Glenn Gould is one of our best classical sellers in the entire market. And, he means more to us than the Juilliard Quartet, even though we like the Juilliard Quartet. Secondly, besides playing this one piece you are playing three quartets by yourselves and also playing with Lenny. It’s going to be a big album. I will make a vow to you. If you let it be released and it gets a bad review, I will take your wives or your girlfriends to the most expensive French restaurant in New York City. You will have a fantastic dinner if you get one bad review.” Well, you know something. We never got a bad review. So we never got a meal.

I have to say something about that recording. I don’t listen to my records at all, but every once in a while someone will tell me that they listened to that Schumann recording. Then I will go and listen to it myself. And when I do, I feel schizophrenic. It’s one of the most thrilling performances you could ever listen to. But as a purist I don’t like it.

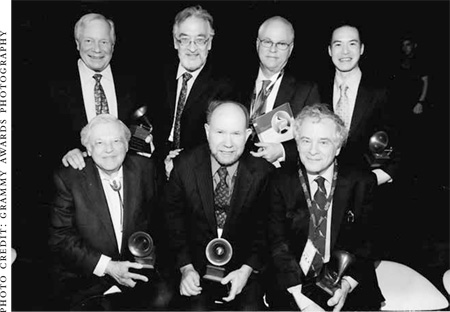

Grammy Awards

In all, the Juilliard String Quartet won three or four Grammys and was nominated many, many times. We won a Grammy for our Ravel/Debussy recording and also for our Bartóks. Actually, the Recording Academy has a Hall of Fame of Recording and our Bartók quartets are in that. In 2011 the Juilliard String Quartet itself was given a Lifetime Achievement award. That was quite a moment. Sitting next to Julie Andrews, who was also being given a Lifetime Achievement award, I thought about how lucky I have been to be successful doing what I love.

Past and present members of the Juilliard String Quartet at the Lifetime Achievement Awards ceremony, 2011

Robert and Julie Andrews at the Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony