Oscar Kokoschka

The summer after we played the Bartóks at Tanglewood, we stayed on South Mountain. I brought Lucy with me. At the same time, Oscar Kokoschka, the great expressionistic painter, had been hired by the people who ran South Mountain to teach an enormous class of painters. He immediately heard that the Juilliard String Quartet was studying and practicing and playing Schoenberg’s third and fourth quartets. He was a great friend to Schoenberg and a lover of music and he asked permission to attend our rehearsal. That’s how Kokoschka became a great friend to both Lucy and myself.

Later on, wherever the Juilliards played and Kokoschka was near us, he would show up with his wife Ann Ilda. For instance, when we played in Switzerland or Lausanne, he was there. I remember once we were invited by the daughter of Queen Elizabeth of Belgium, who had married the exiled king of Italy and ended up moving to Portugal for the rest of his life. In any event, the daughter had set up a chateau near Geneva. She wanted to emulate her mother, who had set up the Queen Elizabeth prize and competition and who had also played chamber music. The daughter wanted to start a contemporary music series in her chateau, about 18 kilometers east of Geneva. The Juilliard String Quartet was invited to open the series and our program would be the five pieces of Webern, the first and third Schoenberg string quartets, and then the five Webern pieces repeated. She invited critics, musicians and friends from Paris, Berlin and all over. And, Oscar Kokoschka came to this concert too.

Drawing of Robert by Oscar Kokoschka

Anyway, our second violinist Bobby Koff had an irrepressible sense of black humor. We were shown a corner of an enormous grand room where we were going to play. And, when we were practicing all of a sudden a tall, thin gentleman wearing medals came up to us and said, “La Reine, the queen would like to meet you.” So, the Queen approached us and we all stood up. The Queen was holding the score of the third Schoenberg string quartet. She said to us, very politely in English, “You know I’ve been studying this quartet that you are going to play tonight and I wonder if you can show me something about it that will help me appreciate it more when you play it tonight.” Bobby Koff goes up to her, takes her score out of her hand, turns it upside down and says, “If you read it this way it might make more sense.” She excused herself and left. We nearly died of embarrassment at Koff’s black humor.

After the concert an enormous room was set up for a reception with all kinds of little card tables topped with the most delicious appetizers. Kokoschka came and sat down with us as well as a friend of his, an Italian woman who was married to a very famous European conductor named Igor Markevich. She was introduced to us as a Duchess or something. I said to her, “You know, the quartet has just made one of its first tours of Italy.” I told her that when we were headed to Trieste, our violist, Rafe Hillyer, had arrived one day early. When we joined him, he told us, “Last night I went to a concert played by the La Scala Opera Orchestra and they wouldn’t let them go. They had to play encore after encore after encore.” He said, “We better have all kinds of encores ready because they are nuts for music.” Hearing this we got ready and prepared a few encores. For that concert, first we played a Haydn quartet and there was hardly any applause as we left the stage. Then we played a Bartók quartet and there was even less applause. Then we played the Schubert “Death of a Maiden.” We took a bow, got off the stage and the applause stopped. I said to the Duchess, “You are Italian, can you explain this to me? I thought and was told that the Italians love music. They didn’t like us at all.” The Italian Duchess said, “You have to understand something about us. People think we love music. We don’t. We love words and that’s why we love opera. I mean we just literally hang on to singing words. But chamber music, only a very small group of people like chamber music.” Actually she was wrong. We played in lots of Italian cities and they loved chamber music.

In June of 1972, Lucy and I found ourselves in Switzerland with some time off. Knowing that Oscar Kokoschka was living nearby we contacted him by phone. He told us that he was delighted that we had called and proceeded to tell us that he would love to draw a portrait of me. He asked “When can you come by?” To which Lucy immediately responded, “how about tonight!” And sure enough, we had a dinner date that evening. With violin in hand, we showed up at his house. After a most enjoyable meal with Oscar and his wife, Oscar invited Lucy and me into the living room. His wife excused herself. Oscar brought out a bottle of Chivas and I took out my violin. I proceeded to play Bach while Oscar, seated in a chair, began sketching me using charcoal on large paper. The evening was full of music, scotch, painting, and friendship, with all of us getting quite drunk as the evening wore on. Time after time, Lucy and I would watch in horror as Oscar would tear up what looked like a wonderfully promising sketch. Finally, late into the evening, he called into the other room for his wife. She came in, looked at the drawing he had in hand, and nodded her head in approval. Oscar proceeded to sign the drawing and handed it to Lucy and me. This portrait of me remains, to this day, one of my favorite possessions.

Ink drawing given to Robert by Willem de Kooning

Willem de Kooning

At Juilliard there were some very interesting musicians and artists who had fled the Nazis. One of the most important was an architect, painter and sculptor by the name of Frederick Kiesler, who was friendly with the Juilliard String Quartet. One day he called us and said, “You know, we have a group, who are colleagues, painters, sculptors and we meet once a month down on Eighth Street. We call ourselves the Eighth Street Group. We like to invite guests who are related in the arts, and we would like to have you come and play for us.” Well of course we were thrilled. After we played Kiesler apolozied for not being able to offer us a fee. We told him that we were not expecting to be paid. We were in for a big surprise. Kiesler then introduced us to a young blond artist who said, “I really enjoyed the evening. I have painted all black enamel on white paintings, and I’d like to give each of you one.” That was Willem de Kooning and his painting is on the wall of my apartment. The other three quartet members sold their paintings over the years, but I wouldn’t sell mine. I remember that Rafe didn’t like the de Kooning painting at all and asked Bobby Koff if he liked it and wanted his. He gave it to Koff, and then changed his mind and took it back.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

In 1952, the Juilliard String Quartet spent an evening with Dr. Albert Einstein in Princeton, following a Sunday afternoon concert at the university. Aware of Dr. Einstein’s lifelong devotion to chamber music both as a listener and participant, we offered to play for him at his home. He graciously accepted. A fervent hope inspired a devious plan that necessitated our bringing along an extra viola and the music of Mozart’s two viola quintets. He received us in a genial mood and wearing extremely comfortable attire. As we played both Beethoven and Bartók, he listened a room removed (not wishing for a visual distraction), and, while he did not seem to share the general aversion to twentieth-century music that seemed to infect his fellow physicists, it was evident that Dr. Einstein’s heart belonged to the earlier music.

After the Bartók we launched our surprise attack. Producing the Mozart score and the extra viola, we said, “It would give us great joy to make music with you.” He protested that he had not played for years due to a hand injury. With the insensitive exuberance of youth we persisted, and he, the true scientist recognizing an irresistible force versus immovable object contretemps, gently acceded to the inevitable. Our second violinist handed his violin to Dr. Einstein, and picked up the extra viola himself. Dr. Einstein without hesitation chose the great, brooding G minor quintet.

Supersensitive to the great man’s remark that he had not played in seven years, from the very first sounds we regrouped around Dr. Einstein in complete rapport with his deliberate but purposeful momentum: basking in the warm glow of making Mozart’s music with this disarmingly unassuming human being. Slow, slower, and slowest crept each successive movement. In direct reaction to the slow tempi, the intensity of our manic happiness grew. Dr. Einstein hardly referred to the notes on the musical score (notes in his mind were never to be forgotten), and, while his out-of-practice hands were fragile, his coordination, sense of pitch, and concentration were awesome. The mood of the Juilliard String Quartet as we finished the Mozart was beatific. Time was late; we gathered instruments and reluctantly bid him goodbye.

At the door he, obviously satisfied that we had coerced him to join us, seemed to want to say more than just a thank you for the music. Finally, he remarked, “I love America and American musicians. They are wonderful. My only complaint is that like the tempo of life here in this country, American musicians tend to play their music too fast.” I replied, “You know, Dr. Einstein, I am sorry to report that the Juilliard String Quartet is also accused of this indiscretion.” He was silent—one could sense his thoughts touching on the evening’s Mozart, so unhurried, so lovingly respectful of his own tempo desires. “You are criticized for playing too fast?” He shook his head and said, “I don’t understand why.”

Dudley Moore

Robert and Dudley, after their concert recital, 1981

The Juilliard String Quartet was first invited to the Edinburgh Festival in 1960 to play the Bartók quartets. It was memorable in a few ways. First of all, Isaac Stern was there with us. He had married a wife who didn’t like him to be close to all of his former friends. So we would spend time together in other cities when we could. He flew in early so that he could spend a day with me in Edinburgh. He was also performing, but playing later than the Juilliard String Quartet. He came and we had a wonderful day, and that evening he said, “You know what we have to do? We have to go to something that has just opened, called Beyond the Fringe.” They were a young bunch of boys, two were from Cambridge and two were from Oxford, who were called Beyond the Fringe because their theatrical revue was considered fringe entertainment. Isaac wanted to go hear them because he had heard that they were just terrific. We went and they were fantastic. The audience was just delighted.

After, I went backstage to tell them how enchanted I was. Dudley Moore had played the piano in the show. He was very sweet and he asked me what I did. I told him that I was in the Juilliard String Quartet and we were at the Festival playing Bartók. He told me that he loved Bartók. So I said, “Well, would you like to come to our Bartók concerts?” His answer was yes and that began our relationship that lasted for many, many years. He even played the piano for my daughter’s wedding. Beyond the Fringe was one of the most successful shows in all of theater history. They played in London, New York and worldwide. I used to stay with him in his London house and when he finally moved to America he visited us often. When he moved to Venice, California, I would stay there with him too.

When I visited him, we would spend every single minute that we weren’t eating, reading every single piece of music that was written. We especially loved Bach and would play all of the Bach sonatas for clavier and violin. We played lots of Mozart and many other composers as well. Dudley could sight read anything. An interesting thing about Dudley’s playing was that he never practiced with enormous vigor. Most pianists develop a lot of muscles to have weight and to be able to play strongly on the piano. That he couldn’t do. Therefore, if you asked him to play a Brahms sonata, he’d play all of the notes, but it wouldn’t have the depth of playing. If you picked the right piece for him he was fantastic. He could play Bach and Delius wonderfully.

He didn’t play classical music in concert, however. At one point I said, “Dudley you have to play a concert.” It took a lot of arm twisting and he finally said, “All right, let’s pick a special program.” So we concocted one and I got Hildy Lemogian from the Metropolitan Museum to present the concert on a Sunday morning. We opened with Bach and played a Delius sonata. I also got Joel Krosnick to play with us and all of the press came. That was the first time that Dudley ever played classical music in public, and he was scared silly. It was quite a triumph on every level.

One evening I invited Itzhak Perlman, Walter Trampler, Zara Nelsova, and Ani Kafavian to my apartment for an evening of chamber music. That same night, Dudley was performing his show Good Evening with Peter Cooke. They had a television show in England that was as famous there as the most successful television shows were in the United States. Anyway, after he was finished with the show he was coming over to be with us. When he arrived, I said to the group, “Would you like to play something with Dudley?” Itzhak Perlman, who is very humorous and likes to poke fun at things said, “What can he do? He plays musical jokes, how could he play classical music?” So I replied, “Well, what would you like to play with Dudley? We looked at the group and which instruments we had, and Itzhak said, “Do you have the music for the Chausson concerto for violin, piano and string quartet? I did. Itzhak said, “Well, ask Dudley if he’d like to play it with us.”

Jorge Bolet said playing Chausson honestly is very, very difficult. Dudley looked at the score for about 5 minutes, flipping the pages and said, “I’ll give it a try.” He sat down at the piano and sight read it, note perfect. He had never seen it before, never even knew the piece existed. I saw every one of the musicians with their mouths dropping. After that, everybody was after Dudley to play with them.

I also played a concert with Dudley in Los Angeles that was a big success. My friend, Gerard Schwarz, who was the conductor of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, was conducting a benefit concert in L.A. and I suggested that Dudley play for him. I said, “You know Dudley’s terrific and he is a big person in California. Why don’t we play the Beethoven Triple Concerto?” And so we did, with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and cellist Nathaniel Rosen joining us. It was also suggested that we play the Beethoven Triple with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. They only wanted Dudley and suggested that the Triple Concerto be played with Yo-Yo Ma, however Dudley insisted that I and Nathaniel play the concert with him.

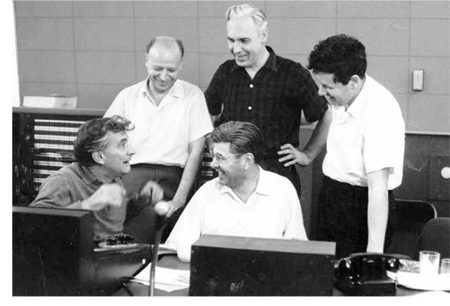

Lenny at recording session with the Juilliard String Quartet, 1959

As time went on, Dudley played more classical music in public, playing with musicians such as Lynn Harrell, the cellist. One of the pieces he began to play was Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. He was one of the most remarkable musical minds that I have ever known. Absolutely.

Leonard Bernstein

In the early 1980s, we played with Leonard Bernstein. We recorded the Schumann quintet and the Mozart G Minor piano quartet with him. The first time we played with him was at the Library of Congress. I remember at one point he asked me where he could find a post office. He had something important that he had to mail. I told him about the post office across the street from the Library of Congress and we walked over. He went up to the teller, a little old lady, and he mailed his letter. She looked up and she saw Leonard Bernstein. She said, “You know you’re a very pleasant looking young man. I hope you have as much success as your famous namesake.” Lenny was wonderful and of course we kept in close touch with him throughout the years, especially when he was giving his famous television lectures on music. I remember studying one of the Bach Brandenburg concertos with him. He would illustrate things. I also remember when he did a contemporary music evening. My God, it was an enormous barn of a studio and it had a full orchestra, a jazz orchestra, a children’s chorus, and he wanted the Juilliard String Quartet. He asked us to play an Anton Webern bagatelle. We got ready to play and we were quietly sitting in our corner and there was all of this pandemonium going on until we approached the live performance of the broadcast. There were four or five minutes left before we were supposed to play. All of a sudden he started clapping and calling for silence. I mean it’s enormous, maybe 300 people in this huge room. Everyone was silent and he said, “All right, Juilliard Quartet, I want to hear Webern before the program starts.” We had chosen the one that starts with three instruments playing from almost no sound slowly growing into a crescendo. All of a sudden he said, “My God, I’ll lose my entire audience. Out.” So we didn’t play Webern. We played Schoenberg instead.

Lenny was a very affable guy but he did have certain attitudes towards tempi. When we played the Mozart with him, he was very strong about the last movement rondo being somewhat slower than we liked to play it. We felt it was because he wanted to protect his playing, and didn’t always have enough time to practice his piano part. But the recording is very good and the quintet is wonderful. Lenny was magnificent.

Menuhin, Ricci, and Stern

Three star violinists began their musical lives in San Francisco: Yehudi Menuhin was born first in 1916, then Ruggiero Ricci, in 1918, and finally, Isaac Stern in 1920. These three stars were recognized in their earliest years, even before grade school, by their parents and teachers as possessing unique gifts. These young men didn’t understand their own abilities even as they began playing their instruments.

Roger, as we called Ricci, possessed the spirit of Paganini: small of stature, with giant hands that encompassed the greatest command of violin playing I have ever known. He played Paganini’s caprices in his sleep. A composer named Vitorio Gianini wrote super athletic variations on the Paganini 24 Variation Caprice, reinventing not just fingered tenths but fingered twelfths. The rest of us were in awe of Roger’s ability to do this. We were jealous.

Yehudi was different. I first heard him in recital in Portland, Oregon. We were both young teenagers. He could move an audience to tears, as he did then with Bach’s Ciaccona. At age 10 he played a masterful Beethoven violin concerto with an orchestra. I was equally talented, but my realm of accomplishment was catching rainbow trout with a fly-rod in Oregon coastal streams.

Many, many years later, I boarded an airplane to Buffalo, New York and found my seat next to Mr. Menuhin, as I called him. Ensuing conversation involved Béla Bartók’s solo violin sonata, which I wanted to learn. I had become passionate about Bartók’s music. Menuhin had commissioned this particular work from Bartók and his recording of it was marvelous. I told him that I had heard he had made a lot of changes that were not in the printed edition. He was very nice about it and said, “I’ll make a copy of the manuscript and send it to you.” In those days you didn’t have Xerox machines. And he did that for me.

To my amazement, I discovered many differences in the manuscript Menhuin sent me. Besides the fact that there were quite a few changes in the first two movements, I found that in the last movement Bartók wrote microtones—in other words, quarter tones. Instead of going chromatically up half tones he went chromatically up using quarter tones and even used some third tones and so on. It had a completely different quality when I looked at it. Menuhin explained that he had suggested changes to the composer and Bartók had complied with alternate passages, the most consequential being the elimination of those micro-quarter tones in the last movement. So, that’s the way I recorded it. After that, everyone in the entire musical world who played the violin said, “Where did you get that version? You know we don’t know anything about that version. It wasn’t in the edition that Menuhin released.” Bartók’s son Peter published it with the original notes and I was teaching those microtones changes to every violinist who wanted to play the piece in its original form. When Peter asked me to record the original version with the microtones, I could not say no. After the record’s release many violinists including Joseph Szigeti asked: “where did you find this different version?”

My acquaintance and friendship with Isaac Stern began in a totally different fashion. I first heard him play in Portland as a kid. I was two days older then he was. We were both born in 1920. I was born on July 19th and he was born on the 21st. He came from San Francisco and as a young violinist played the Saint-Saens B Minor Concerto. I remember how he played it. I didn’t know him, but I remember I went backstage and shook his hand because my teacher was the concertmaster of the Portland Symphony.

In 1939, at age nineteen, while I was attending the Juilliard Graduate School in New York City I developed an extremely painful stomach ulcer. The prescribed treatment was drinking a lot of milk, which I did every day in the school’s student lounge after a class or practicing session, and I would schmooze with people who came in and out. One day a stranger was sitting in that space. He was somewhat older, and didn’t appear to be a musician. After some conversation about the state of chamber music, he said, “You know, I am not a musician. My name is Hy Goldsmith. I’m a physicist who teaches at Columbia University and loves music.” He wanted to know if I enjoyed playing string quartets and I responded with a sweeping critique of what was wrong with most current chamber music performances. I knew everything, you see.

Musical discussion: Robert with Isaac Stern and Sasha Schneider, 1955

He looked amused and quietly said, “I have some musician friends who come to my apartment for informal string quartet evenings. Would you like to come sometime? You will have ample opportunity to demonstrate the proper approach to playing chamber music.” I thought why not and said, ‘when?’ He replied “tomorrow night.”

I took an elevator at the appointed time to the top of his building, the Oliver Cromwell on 72nd Street near Central Park. I landed on the 35th floor and knocked on the door and who should open it but Isaac Stern. I was taken a little aback because I knew that Isaac was a good player. Seeing him, my ulcer cried out, but I entered this physicist’s penthouse domain overlooking major portions of Manhattan to the north, south, east, and west. Quite a few people were already assembled at one end of the large room; they turned out to be a mix of scientists, doctors, professors, and other chamber music lovers all ready to listen. At the other end of the room were four music stands and chairs. The next knock at the door produced William Primrose, the great violist. Now I’m thinking, “What did I get myself into?” A few moments later, in walks the six foot, three-inch Gregor Piatigorsky holding his cello case with one hand.

After some introductory social interplay I quietly sat down with my violin in the second violin chair, waiting for my eminent new colleagues to produce music on the stands and join me for an evening’s reading of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms. We slowly tuned up to the 440A pitch given by Isaac. Just as we were about to start, Hy Goldsmith, my scientific host and new friend, leaned down and whispered into my ear, “Okay, Bob, show us what chamber music is all about.” Chamber music is a different medium than concertos and virtuosic athletic show-off pieces. This was the music that I had cut my teeth on from an early age. Surprisingly, and much to my relief, I could easily hold my own place with the eminent others.

Robert with Dorothy Delay and Itzhak Perlman, Perlman Master Class, Juilliard, 1989

Itzhak Perlman

I first heard about Itzhak Perlman from Dorothy Delay, who was at that time Ivan Galamian’s assistant at Juilliard. She told me that I had to hear this young violinist who was only thirteen years old, studying with them and an amazing talent. Later, when Itzhak was a bit older, he would come and play for me in our apartment north of Juilliard, which was then on 123rd Street and Broadway. It was actually Toby, Itzhak’s girlfriend (and future wife) who pushed him to do so, because, she said, I was one of the few people who would tell him the truth about his playing! Toby, herself a violinist, was studying chamber music with me at the time and loved how I challenged them to think about the music. She wanted Itzhak to have that experience too. Toby and Itzhak would also come just to visit Lucy, me, and the kids, and Toby would help our son Nicholas to practice. We would hang out, enjoy each other’s company, and became close friends.

Through the years I have seen Itzhak become a superstar. My respect for his musical ability is profound. Our collaborations have taken many forms, including his premiering (with Sam Sanders) a composition, Chiaroscuro, I wrote especially for him, at a Carnegie Hall recital in 1975. Our friendship is a history filled with tremendous memories and shared experiences.

Seiji Ozawa

There is no one, besides my quartet colleagues, with whom I have a more deeply meaningful musical relationship than the conductor, Seiji Ozawa. I first heard of Seiji’s remarkable talents from his teacher and my friend, Hideo Saito, at the Toho School in Japan. Over the span of the next fifty years, I had the joy to collaborate and work with Seiji on numerous occasions.

I have many fond memories of teaching at Seiji’s International Academy for quartets in Switzerland, and have performed, conducted, and taught over the years at his Matsumoto Festival in Japan. My bond with Seiji is both personal and musical, but at the heart of it lies our shared set of core musical values. It was only fitting that my very last concert with the Juilliard String Quartet took place in Tanglewood, in the Ozawa Hall, with Seiji in the audience.

Robert with Seiji at his International Academy

PHOTO CREDIT: TANIMICHI OKUBO

Modern Jazz Quartet, John Lewis, Billy Taylor

In the early days the Juilliard String Quartet played with the Modern Jazz Quartet. John Lewis and his quartet were marvelous guys. I don’t know how we got together but we played quite a few concerts with them. We were even invited to play a joint concert in Carnegie Hall. We played first, I think it was Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden.” Then the Modern Jazz Quartet played, and then we played arrangements that John Lewis made for us to play together. Of course the audience was absolutely wild, and we had to go out and play encores. We had rehearsed John Lewis’s version of the D Major Suite for string orchestra. Right when we were ready to go out on the stage, I realized that I didn’t have my music—and we had only gone through it once. So in front of almost three thousand people I improvised my part, and John Lewis was smiling at me the entire time.

We also later played with Billy Taylor and his Trio. We even received a commission in Wisconsin for Billy Taylor to write a piece for string quartet and jazz trio, Homage.

The Smothers Brothers Television Show

The Juilliard String Quartet was asked to play on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour television show in 1968. Although some people said we shouldn’t do it and then criticized us for “stooping so low,” Josef Gingold, one of the great violin teachers said “More people watched you on that show than all the people in the audiences in the history of the Juilliard String Quartet combined.”