Teaching

In the early Juilliard String Quartet days, we were not given the role at Juilliard to teach chamber music. Hans Letz, a German violinist who had been concertmaster of the Chicago Symphony and played with the Kneisel Quartet, was still very alive and teaching quartets at Juilliard. I was given the job of teaching sonatas with a class of ten violinists and three pianists. At first, I was very frightened because most of the players could play rings around me as instrumentalists. After I heard them play I realized that their technique was built for Paganini and show-off music. When it came time to play Beethoven and Mozart I knew more about the technique of producing the sound and the phrasing than they did. I was very relieved. I was also very free-wheeling. If it was a beautiful day, I would suggest to all of the students in my class to take a nice hike. So we would walk down to the ferry on 125th Street, and I would pay the five cents each that it would cost to go over to New Jersey. Then we would walk on the trails along the Hudson River. There were no buildings on the other side. We would walk to the George Washington Bridge which wasn’t finished yet, and climb on the bridge and walk back to New York.

In the mid-1980s, the Juilliard String Quartet taught at Michigan State University in East Lansing (see Part V). One of the quartets we taught was from China, brought over to Michigan State by Walter Verdhr. I was coaching this quartet, and the violist seemed very uncomfortable. He didn’t seem to be a natural violist and I mentioned this to the interpreter. The interpreter told me that a few months earlier an order came from Beijing that fifty violinists would have to become violists. That is how he began playing the viola.

Robert coaching at Seiji Ozawa’s International Academy, Switzerland

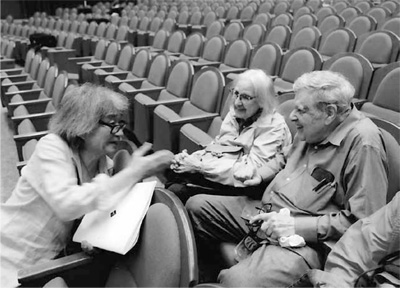

Robert coaching at the Robert Mann String Quartet Institute, Manhattan School of Music, 2012

When I left the Juilliard String Quartet, I still was a strong teacher of chamber music at both Manhattan School of Music and Juilliard. I love teaching chamber music. I think that everyone who has spent an enormous amount of time and involvement in their art form doesn’t want to just impart those things through a single performance to an audience. I always found that getting young people to play the way I felt about the music was one of the most fulfilling things in my life. There is nothing more important than imparting your knowledge and inspiring the next generation with your passion. Every year since the early days I have taught about five or six quartets. After retiring from the Juilliard String Quartet in 2012, I began The String Quartet Institute at the Manhattan School of Music. A week of intensive quartet coaching, with daily master classes, streamed live, has been a highlight of my teaching life. Numerous young talented quartets have participated, too many to name. There is nothing I find more rewarding than exploring the world of quartets with the young, bold, and adventurous groups of today. Taking in what we give them, the quartets that we have taught then develop an equally meaningful way to perform the music. Hearing them find their own voice gives me the greatest pleasure of anything.

Robert at Seiji Ozawa’s International Academy, Switzerland, 2009

Conducting

I had a talent for conducting. People said that I was a good conductor and for a short time I began to contemplate maybe being a conductor rather than a violinist. I always found that for me playing the violin was a struggle and I didn’t find that with conducting. The main problem with conducting isn’t how you physically move your body in relationship to the players you conduct, but is knowing the score. I mean you really have to know the score backwards and forwards. I would memorize the score. In the end, however, I couldn’t give up playing chamber music.

Robert conducting the International Academy student orchestra, Switzerland

Composing9

IN THE WORDS OF NICHOLAS MANN (1992):

At Juilliard my father studied composition with Wagenaar, who opened his eyes to Schoenberg and Berg. He also met Stefan Wolpe, who took an interest in his compositions and greatly influenced his compositional development. He also benefited from his role as arranger, transcribing everything from Rhapsody in Blue to Scheherazade, to even the Brahms Double for piano trio.

Very early on my father became interested in setting words to music. When he met my mother he had an added inspiration—she was an actress. He began to put the fairy tales of Hans Christian Anderson and Just So Stories by Kipling to music for violin, piano, and narrator. One year my parents made a tape of them to send to friends for a Christmas present. They were so well received that the Lyric Trio was born, and my father began composing for narrator in earnest. There are probably more than thirty works he has written in this genre. Several of them are recorded on Bartók Records and the Baca Ensemble on Musical Heritage. My sister, Lisa, and I began to join in giving children’s concerts that centered around these works (we became the Lyric Trio + Two). Recently my father has set both Native American and Chinese poetry to music.

One of my father’s first major successes as a composer came as a result of the conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, who was an early supporter of the Juilliard String Quartet. Mitropoulos saw a narration work of my father’s entitled “The Terrible Tempered Conductor.” He was very impressed with the work but was bothered by the humorously negative image of a conductor. He asked my father to write another piece for him to perform. This was the origin of “Fantasy for Orchestra.” On finishing the work my father brought it to Mitropoulos during the intermission of a New York Philharmonic concert. Mitropoulos noticed that the work ended softly. “Couldn’t you bring back a climactic moment to end the work? Soft endings are so problematic.” Unhappy, but not wishing to lose a unique opportunity to have his piece performed, my father agreed to the suggestion. Elliott Carter, Pierre Boulez and Peter Mennin came to hear the New York Philharmonic at the dress rehearsal. Carter turned to my father: “very good but it sounds like you tacked on the ending.” My father’s respect for Carter as a composer immediately grew greater. But maybe Mitropoulos was correct. The work was a success and Mitropoulos took it on tour to Vienna and Salzburg with the Vienna Philharmonic10.

Those people who are unaware of my father’s life as a composer are always surprised by the large output of his compositions. The La Salle and Concord String Quartets performed his “Five Movements for String Quartet.” Itzhak Perlman commissioned a duo and premiered it with Sam Sanders in Carnegie Hall. My father has also written a duo for cello and piano for Joel Krosnick and Gil Kalish. This past December the Juilliard Symphony premiered his “Concerto for Orchestra” in Alice Tully Hall, with the composer also serving as conductor—another of his little-known but often performed roles.

Those who have worked with my father as teacher are aware of how strongly he feels that to truly understand the creative process the performer, or re-creator, should experience the world of creation. For my father though, composing is not just a hobby but a real passion and an important part of his musical life. He has never pursued the political necessities of furthering his career as composer. He simply loves to compose and has something special to offer the musical world.