Mencius and The Late Beethoven String Quartets

The inspiration for this exploratory expedition up the front face of the late Beethoven String Quartet massif arose like the phoenix out of the ashes of two separate reactions. The first has been annoying me for years, ever since the moment my non-musical brother challenged me to prove that the ‘Lento assai’ movement of Beethoven’s Opus 135 was of more import to the human race than the popular melody, “White Christmas.” If only my brother had restricted his challenge to the arena of interpretive talent, we could have debated happily whether the Juilliard Quartet’s rendition of the ‘Lento assai’ was more moving or not, than Bing Crosby’s rendition of “White Christmas.” Unfortunately, while everyone recognizes that popularity alone does not carry its own guarantee of permanence, no one yet has set up a fool proof standard of measure for a musical composition that avoids value judgements involving subjective or cultural attitudes.

The second reaction was the result of a more recent, “green tea” discussion in Wei Ming Tu’s Berkeley, California garden. Wei Ming is a remarkable Chinese scholar, so when he spoke about Mencius and the application of this great Confucian’s analysis of human nature to the aesthetic realm, the very idea inspired a continuing internal dialogue of my own on how Mencius might have regarded a late Beethoven string quartet.

The philosopher, known today as Mencius, was Meng-Tzu or Master Meng, born a little over one hundred years after the death of Confucius in the region of Shantung Province in China. He became, after the Master, the greatest influence on the School of Confucianism in China. He believed that human nature was essentially good; evil evolving only as one strayed from his original ability to love and commiserate, to distinguish right from wrong.

What does the music composed by Ludwig van Beethoven born in Bonn, Germany in Europe, 2100 years later have to do with ancient Mencius? I would begin by stating that Beethoven shared Mencius’ belief in man’s inherent good nature. Before I am finished I will dare to suggest that they shared much more than that. Up to the year 1823, Beethoven commanded the serious respect, love and admiration of his fellow musicians and the entire European musical community. However, as his deafness increased, he retreated into the silent places where his incredible imagination roamed. The musical world found it more and more difficult to follow him. Thus, that extraordinary musical mountain range known to us as the Late Quartets came into being, lifted into dizzying stratospheres during the four last years of Beethoven’s silent existence. Noise, spoken words and other musician’s music could not reach him, and his inner, creative furnace, like that of the uninhibited, Hawaiian Goddess Pele, forged into musical reality, terrifying peaks teeming with un-scalable cliffs, well protected by strange foothills of mystifying, musical materials that even the experienced musical explorer and climber could not easily traverse.

It took only three years for Beethoven to create five separate, unique musical mountain massifs with at least one unclimbable Everest, the Great Fugue.

The year 1824 saw the composition of Opus 127, Opus 132 and Opus 130 with the great fugue as last movement were completed in 1825. Opus 131 and Opus 135 and the alternate last movement Rondo for Opus 130 were finished in 1826, a few months before Beethoven’s death in early 1827.

Everyone was awestruck or mystified as to how to approach these works. A small band of true believers eagerly prepared to assail these cliffs and precipices, no matter what the dangers. Beethoven himself was well aware of their inherent difficulties; both to perform and understand. His note to the members of the Schuppanzigh Quartet read as follows:

“Best Ones”—Each one is herewith given his part and is bound by oath and indeed pledged on his honor to do his best, to distinguish himself and to vie with each other in excellence. Each one who takes part in the affair in question is to sign the sheet.

(Signed) Beethoven

A contemporary ear-witness, a Mr. Smart from England described the first attempt on Opus 127 thus:

“Not enough room to sit down. The four quartet players had hardly room for their stands and their chairs. They were some of the best virtuosi of Vienna. They had dedicated themselves to their difficult task with the whole enthusiasm of youth and had held seventeen rehearsals before they dared play the new enigmatic work. The difficulties and secrets of Beethoven’s last quartets seemed so insurmountable and inscrutable that only younger, enthusiastic men dared play the new music while the older and more famous players thought it impossible to perform. The listeners were not permitted to take their task easily. It was decided to play the work twice.”

I regret to report that this valiant, first attempt on Opus 127 by Beethoven’s Schuppanzigh Quartet failed. Beethoven somewhat ungratefully, (and I think, being a first violinist in a quartet, myself, unfairly), blamed the failure on Schuppanzigh. Unfortunately the whole quartet was roped together and if one failed, all failed. Schuppanzigh himself, confessed that he could easily master the technical difficulties but it was almost impossible to arrive at the spirit of the work. By the time Beethoven died, he had watched (he could not hear) attempts on Opus 127, 132 and 130. The year 1828, after his death, marks the first expedition up the massif of Opus 131. It has been a modern illusion that these intimidating, musical challenges were not only misunderstood but also ignored. Research has proven this to be untrue. It is known that even such virtuosi as Paganini, Wieniawski, Servais and Vieuxtemps loved to play these works. By the year 1875, (when Wagner wrote his essay on Opus 131) there is evidence of at least 1,039 public expeditions up the various late Beethoven peaks; 260 on Opus 131 alone. Even New York City witnessed three attempts on Opus 131, Boston, two.

But while the musical world has become more and more involved and obsessed with the meaning of the late quartets and their challenge to the human body and spirit, the success of reaching the rarified atmospheres of each work whatever route one chooses remains almost as elusive and unique as when they first appeared on the human horizon.

I personally was terrified by the late quartets in my early years. Gently, but firmly, loving teachers have guided me through their foothills. Slowly but surely I learned to survive for long periods of time in the region where these works exist. Out of my over forty years of group-playing with these five musical giants has come my deep conviction that they represent the most important influence of my musical life.

Yet I would be the first to disclaim that I comprehend what Beethoven intended. It is even possible to suspect that even Beethoven didn’t fully comprehend what he had wrought: that is why I now turn to the ancient sage, Mencius, for help.

Mencius postulated six exceptional steps up the ladder of “self-cultivation.” He who commands our liking is called (SHAN)—good. He who is sincere with himself is called (HSIN)—true. He who is sufficient and real, is called (MEI)—beautiful. He whose sufficiency and reality shine forth, is called (TA)—great. He whose greatness transforms itself, is called (SHENG)—profound. He whose profundity is beyond our comprehension is called (SHEN)—spiritual.

According to Wei Ming Tu, Mencius maintained that this spirituality, this greatness that transforms itself, that is beyond comprehension, represents a symbol of a higher station of being on the very same path as good, truth and beauty. He believed that while few might attain spirituality it was a potential for all. I might paraphrase this to say that while few might create as Beethoven did, the path for the interpreter, performer and listener is essentially the same path that Beethoven traveled.

Mencius reveals a clue relevant in the approach to late Beethoven when he emphatically states that the way of learning consists of none other than the quest for the lost heart, when he holds that the body can hardly express the feelings of the heart even though it is the proper place for the heart to reside. The Mencian heart is both a cognitive and an affective faculty. It not only reflects on realities, but in comprehending them, shapes and creates their meaningfulness for the human community as a whole.

The Confucian view accepts a human being as part of the whole rather than the end all (unlike Protagoras, the Greek philosopher who said, “Man is the measure of all things.”) This Confucian attitude is vital to the understanding of Beethoven and his last works. To put it another way, completion of self necessitates the completion, not domination of things.

For Mencius, aesthetic language (such as embodied in Opus 131) was not merely descriptive, but it suggested, directed and enlightened. To respond to such a work, both the performer and the listener must bring to it what Mencius viewed as the vital spirit endowed with what might be termed, “matter-energy,” a power connected to breathing and blood flow. Authentic music therefore does not create a fleeting impression on the senses, but possesses enduring virtues. There is a quaint account in Confucian analects that after hearing the music of SHAO, Confucius was in such a state of beautiful enchantment, that he could not distinguish the taste of meat for three months afterward.

By looking again at Mencius’ six stages of human self-cultivation we may find in them just that elusive standard of measurement of enduring artistic value.

Stage 1: That music, which commands our liking, is called good. That music is good which is entertaining, which is understandable, that pleases. That music is good which you wish to experience again, that intrigues, that doesn’t offend. That music is good which one may not like but which is liked by others.

Stage 2: That music, which is sincere with itself, is called true. That music is true which delivers what it promises, which is consistent, logical, unassuming, which does not pretend to be other than what it is, and speaks in its own voice, adhering to its own way whether it be pleasing or not; which, after repeated hearings or passage of time, still evokes a positive response in the listener.

Stage 3: That music, which is sufficient and real, is called beautiful. That music is beautiful which is both substantial and conclusive which stands for something no matter how big or small. That music is beautiful in which the cliché or predictable musical sequence does not dominate the course of musical events; in which the emotional affects aroused by the music may strain or challenge the boundaries of the music’s structure but never distort or destroy it.

Stage 4: That music whose sufficiency and reality shine forth, is called great. That music is great which arouses tingling of the spine, open breathing and the formation of tears. That music is great which not only stands apart from other music of its kind, but contains special, magical moments or lucky accidents (as Stravinsky called them). That music is great which one is drawn towards and held a willing captive no matter how much one has experienced it previously. That music is great which, when experienced, remains enduring and memorable.

Stage 5: That music whose greatness transforms itself; is called profound. That music is profound in which the whole is greater than each part; which in effect transforms the person experiencing it. That music is profound which when it is simple appears complicated and when it is complicated, appears simple. That music is profound which as it evolves appears to become something new or other than it has ever been previously.

Stage 6: That music, whose profundity is beyond our comprehension, is called spiritual. That music is spiritual in which its vital force does not drain but on the contrary, recharges the emotional state of the listener. That music is spiritual which mixes the logical with the illogical, the rational with the irrational, whose physical manifestation is always ingenious. That music is spiritual in which one can know every sound and silence, may even have an understanding of its physical properties, yet whose effect while spell-binding and powerful, nonetheless, in the last analysis, remains unfathomable, mysterious, elusive and tantalizing.

I have discovered that my lifelong involvement with the five last quartets of Beethoven is definitely Mencian. I would describe the continuous sounds and silences of Beethoven’s last quartets as pathways or vessels through which the music conceived in Beethoven’s mind, moves. I would argue that the music of the mind is only as good and true as it is touched on by the heart; and further, this “mind-heart” power that Mencius refers to as CH’I, remains the motivation and means to achieve the oneness of heart and body, spirit and mind.

We observe that animals expend life energy out of functional need. Humans can strive (if they are possessed of CH’I) to harness that energy for emotional and artistic functions. Obviously Beethoven was in agreement with Mencius, not only about the human spirit, but about the power of an aesthetic language that draws creative sustenance from oneness with nature and the inner heart.

What about the modern day Schuppanzighs and Mr. Smarts, (performer and listeners) as we prepare for the experience of these awesome works? For the performer, the Confucian master, Mencius penetrated to the heart of the matter. He made a clear distinction between unwillingness and inability. He was keenly aware of the difference between rote performer and active participant. How did a rote performance reveal itself? By a lack of intensity, a concentration on the external form as a basis for truth and beauty; and by focusing not on the result but only on the means by which the result was attained. The master was not content that the student achieves the correct form. He tried to enable the student to create his own style, his own interpretation. In our present time, when most foods reach us in packaged form; where hotel rooms in New York, Cairo or Tokyo look essentially the same; piped in music in buildings sounding essentially the same; while we expect our machines to function at all times precisely and efficiently; it is not surprising that most career musicians, most audiences and critics are satisfied with technically superior, rote performances. Perhaps the best advice for the performer in the twentieth century about to play a late Beethoven quartet is Mencius’ sixth century assertion that, the capture of the heart or profound meaning should be understood as ‘the art of steering, involving a process of adjusting and balancing on unpredictable currents.’

For the listener about to hear a performance of a late Beethoven quartet I would advise that the opening of the heart and the emptying of the mind is of more importance than a conscious and perhaps artificial effort to count and catalogue the external materials and events along the way. Leave that activity to the critics and musicologists. I would caution that knowledge of the score and repeated encounters with the composition are illuminating only if, after thorough digestion and absorption into the less conscious self, they support and abet the spontaneous and vulnerable experience. Certainly they are not helpful if they become the focus and preempt the central preoccupation of the relationship between the music and the participants.

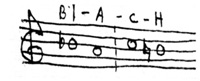

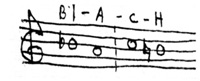

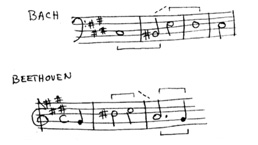

Joseph Kerman in his book on the Beethoven quartets writes that: “Each of the late quartets provides us with a separate paradigm for wholeness. Total integrity arising out of individuality of form, feeling and procedure.” Maynard Solomon refers to the sense of ‘pain and its transcendence’ in Opus 131. Being the true musicologist, he also counted six main keys, thirty-one tempo changes and ‘a variety of forms that move from fugue, suite, recitative, variation, scherzo, aria to a final sonata form. Erich Schenk makes the most interesting observation about the late quartets by showing how Beethoven’s last creative urges were deeply influenced by the baroque period; preoccupation with chromatic melancholy conceptions that might be described as portraying pain, sorrow, trespass and preparedness for death: Beethoven, the 19th century revolutionary composer emulating Bach in his upward striving, constantly defeated melodic shapes and his obsession with the intensity of a single note building towards resolution one half step down or up. It is a curious fact that Beethoven entertained during the last years of his life, the idea of composing an overture based on the musical signature of J.S. Bach:

Simply analyzed, this remarkable group of notes consists of a single note (B-flat) resolving one half step down to (A-natural) and this two note pattern repeated at a higher level (C-flat to B-flat). These two groups are connected by a less intense interval (the A-flat to the C-flat) a minor third.

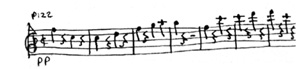

Now examine the first theme in the first movement of Beethoven’s Opus 130:

Three two-note groups containing the half step resolution with a less intense interval of a minor sixth connecting the second and third groups.

The main theme of the big fugue last movement is even more revelatory. The interval groups are:

Four groups of two notes, three of them resolving up and only one down. The first group connected to the second by a major sixth, the second to the third by a minor sixth and the third to the fourth again by the interval of a major sixth. A larger pattern of four notes repeated at a higher level can be likened to the Bach signature stated twice.

It is surely no accident that Beethoven, who loved Bach’s Well Tempered Clavichord fugues, created his opening fugal theme in Opus 131 with Bach’s C-sharp minor fugue in his mind:

In both Bach’s and Beethoven’s themes there exists two half step groups connected by an interval of a major third (Bach’s actually is spelled as a diminished fourth but sounds as a major third). Richard Wagner in his 1875 essay on Opus 131 refers to Beethoven’s opening theme in Opus 131 as ‘surely the saddest thing ever expressed in notes.’

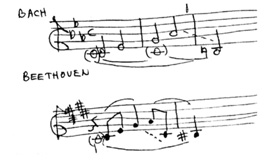

This close Bach-Beethoven link continues in Opus 131. If we compare Bach’s theme (Frederich’s?) in the ‘Musical Offering’ with the opening motive in the last movement of Opus 131:

Again the two note pattern of a half step influenced or disturbed by the sound of an interval of the sixth. The opening motive of Opus 132 continues this mystery.

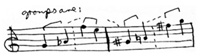

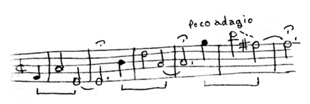

And finally, in Opus 135, the ‘difficult question’ motive of the last movement:

And later at the coda:

Beethoven pronounced his last five string quartet creations great; “each in its own way.” I would submit to my non-musician brother that while “White Christmas” may aspire as high as Stage 3 on Mencius’ score card, the Lento assai of Opus 135 and indeed all of the towering creations of Beethoven’s last quartets pass every (Mencian) test of greatness and spirituality without contest. I am well aware of the conceit of my argument. No one can “prove” greatness in music any more than one can put a “price tag” on the value of human life. While these musical compositions may be beyond our musical comprehension, we can certainly think on Beethoven as we contemplate Mencius’ dictum: “The great man does not lose his childlike heart.”