CHAPTER 3

LANGUAGE CONTACT IN EARLY COLONIAL NEW SOUTH WALES 1788 TO 1791

THE BEGINNING OF CONTACT

It is well-known that on 26 January 1788 England established its first settlement in Australia at Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. Less well-known are the linguistic consequences of that settlement. The aim of this chapter is to describe some of the earliest linguistic interactions between the indigenous people of the Sydney region and the members of the First Fleet who, led by Governor Arthur Phillip, established the colony of New South Wales.

Contact between Aboriginal people and colonists first occurred at Botany Bay where, by 20 January 1788, the First Fleet was anchored. Simple verbal exchanges and much use of gesture seemed to achieve the desired results, at least from the colonists’ point of view:

This appearance [of a large number of Aboriginal people] whetted curiosity to its utmost, but as prudence forbade a few people to venture wantonly among so great a number, and a party of only six men was observed on the north shore, the Governor immediately proceeded to land on that side, in order to take possession of his new territory, and bring about an intercourse between its old and new masters... At last an officer in the boat made signs of a want of water, which it was judged would indicate his wish of landing. The natives directly comprehended what he wanted, and pointed to a spot where water could be procured... As on the event of this meeting might depend so much of our future tranquillity, every delicacy on our side was requisite. The Indians, though timorous, shewed no signs of resentment at the Governor’s going on shore; an interview commenced, in which the conduct of both parties pleased each other so much, that the strangers returned to their ships with a much better opinion of the natives than they had landed with; and the latter seemed highly entertained with their new acquaintance, from whom they condescended to accept of a looking glass, some beads, and other toys. (Tench 1979, 35)

The author of this account, a senior officer named Watkin Tench, also described an encounter during the exploration of Botany Bay:

We were met by a dozen Indians... Eager to come to a conference, and yet afraid of giving offence, we advanced with caution towards them, nor would they, at first, approach nearer to us than the distance of some paces. Both parties were armed; yet an attack seemed as unlikely on their part, as we knew it to be on our own... After nearly an hour’s conversation by signs and gestures, they repeated several times the word whurra, which signifies, begone, and walked away from us to the head of the bay. (Tench 1979, 36)

The colonists decided that Botany Bay lacked the resources necessary for a settlement. They investigated Port Jackson and chose Sydney Cove as the site for their base. The Aboriginal people of Sydney showed some interest in the newcomers and this encouraged Phillip in his hopes that permanent communication could be established. His orders from the King of England were to open free communication with the indigenous people of Australia to convince them that although their country was to be colonised, they would be treated well and would live in harmony with the colonists:

You are to endeavour, by every possible means, to open an intercourse with the natives, and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all our subjects to live in amity and kindness with them. And if any of our subjects shall wantonly destroy them, or give them any unnecessary interruption in the exercise of their several occupations, it is our will and pleasure that you do cause such offenders to be brought to punishment according to the degree of the offence. You will endeavour to procure an account of the numbers inhabiting the neighbourhood of the intended settlement, and report our opinion to one of our Secretaries of State in what manner our intercourse with these people may be turned to the advantage of this colony. (George III 1787, 485)

The establishment of a common language, at least between the colonial administration and the local Aboriginal people, was thus a high priority for Phillip.

Aboriginal people in the Sydney area visited the settlement and elementary communication began to develop. Phillip’s strategy involved the use of a short vocabulary of the Guugu Yimidhirr language collected by Captain James Cook’s expedition in 1770 at the Endeavour River, northern Queensland. This language is completely different from the languages of the Sydney district and attempts to use the vocabulary were therefore singularly unsuccessful. One product of the experiment was that, for a while, Sydney Aboriginal people thought that the colonists’ word for all animals except dogs was the word derived from Guugu Yimidhirr ‘kangaroo’. Conversely, the colonists thought the area in which they settled had little fauna because the Aborigines called all animals ‘kangaroo’:

We have never discovered that...they know any other beasts but the kangaroo and dog. Whatever animal is shewn them, a dog excepted, they call kangaroo: a strong presumption that the wild animals of the country are very few... Soon after our arrival at Port Jackson, I was walking out near a place where I observed a party of Indians, busily employed in looking at some sheep in an inclosure, and repeatedly crying out, Kangaroo, kangaroo! As this seemed to afford them pleasure, I was willing to increase it by pointing out the horses and cows, which were at no great distance. (Tench 1979, 51)

Much later, the colonists realised that they had inadvertently taught the local Aborigines a word from another Aboriginal language:

Kanguroo, was a name unknown to them for any animal, until we introduced it. When I showed Colbee the cows brought out in the Gorgon, he asked me if they were kanguroos. (Tench 1979, 269)

In spite of the seemingly amiable start to cross-cultural relations, Aboriginal people very soon became offended by the presence of the colony. Phillip was unable to prevent colonists from stealing the possessions of Aboriginal people and physically attacking them, and the Aboriginal population retreated and refused to have anything to do with the settlement.

THE FIRST LINGUISTIC EXPERIMENT: THE CAPTURE AND TRAINING OF ARABANOO

Phillip was very disturbed by the breakdown in communication. He attempted to control acts of aggression towards Aboriginal people by severely punishing offenders. Aboriginal people also retaliated violently and Phillip feared a full-scale war.

The need to establish communication became urgent. As it seemed impossible to entice Aboriginal people into the settlement where linguistic interaction could be achieved naturally, Phillip decided to capture a number of people, force them to learn English and then use them as interpreters:

It being remarked with concern, that the natives were becoming every day more troublesome and hostile, several people having been wounded, and others, who were necessarily employed in the woods, driven in and much alarmed by them, the governor determined on endeavouring to seize and bring into the settlement, one or two of those people, whose language it was become absolutely necessary to acquire, that they might learn to distinguish friends from enemies. (Collins 1975 vol 1, 40)

In December 1788 Phillip’s plan succeeded and Arabanoo became the first Aboriginal captive of the British and thereby the first Aboriginal person to enter into prolonged communication with the colonists. He was described as a poor but willing learner. There is no detailed description of the processes used in teaching him English although it is certain all the administration participated in the endeavour. When he acquired a word, it was observed that he could extrapolate to other similar items. Arabanoo supplied information about Aboriginal society to the colonists and errors of understanding were corrected as communication became more effective.

The colonists began their experiments by exposing Arabanoo to their own culture and language and watching him for his reactions in order to understand something of his culture and language. They noted words he used in his own language that they supposed described his experiences:

To prevent his escape, a handcuff with a rope attached to it, was fastened around his left wrist, which at first highly delighted him; he called it ‘Ben-gàd-ee’ (or ornament), but his delight changed to rage and hatred when he discovered its use...seeing the smoke of fire lighted by his country men, he looked earnestly at it, and sighing deeply two or three times, uttered the word ‘gweè-un’ (fire). (Tench 1979, 141)

Eliciting Arabanoo’s name proved to be a great challenge and it took until February to solve the mystery:

Many unsuccessful attempts were made to learn his name; the governor therefore called him Manly, from the cove in which he was captured: this cove had received its name from the manly undaunted behaviour of a party of natives seen there, on our taking possession of the country. (Tench 1979, 141)

Tench attributed their eventual success to Arabanoo’s increased confidence:

His reserve, from want of confidence in us, continued to wear away: he told us his name, and Manly gave place to Ar-ab-a-noo. (Tench 1979, 143)

The colonists’ main objective was to teach Arabanoo English and ‘he readily pronounced with tolerable accuracy the names of things which were taught him’ (Tench 1979, 140). Pictures were also employed by the colonists in their sociolinguistic experiments with Arabanoo:

When pictures were shewn to him, he knew directly those which represented the human figure: among others, a very large handsome print of her royal highness the Dutchess [sic] of Cumberland being produced, he called out, woman, a name by which we had just before taught him to call female convicts. Plates of birds and beasts were also laid before him and many people were led to believe, that such as he spoke about and pointed to were known to him. But this must have been an erroneous conjecture, for the elephant, rhinoceros, and several others, which we must have discovered did they exist in the country, were of the number. Again, on the other hand, those he did not point out, were equally unknown to him. (Tench 1979, 140)

Music was another medium employed in Arabanoo’s enculturation: ‘...he had...shown pleasure and readiness in imitating our tunes’. (Tench 1979, 142)

Arabanoo came to be well-liked by the colonists for the ‘gentleness and humanity of his disposition’ (Tench 1979, 143). It was observed with approval that:

...when our children, stimulated by wanton curiosity, used to flock around him, he never failed to fondle them, and, if he were eating at the time, constantly offered them the choicest part of his fare. (Tench 1979, 143)

When Hunter met Arabanoo for the first time in May 1789 he commented on his excellent memory for names and his mild nature. He also commented on Arabanoo’s use of an Aboriginal word for boat. This indicates that Arabanoo was mixing English and Aboriginal words when he knew the meaning would be understood:

He very soon learnt the names of the different gentlemen who took notice of him, and when I was made acquainted with him, he learnt mine, which he never forgot, but expressed great desire to come on board my nowee; which is their expression for boat or other vessel upon the water... The day after I came in, the governor and his family did me the honour to dine on board, when I was also favoured with the company of Ara-ba-noo, whom I found to be a very good natured talkative fellow; he was about thirty years of age, and tolerably well looked. (Hunter 1968, 93)

Arabanoo’s gradual enculturation was noted, particularly with regard to everyday matters:

Bread he began to relish; and tea he drank with avidity: strong liquors he would never taste, turning from them with disgust and abhorrence. Our dogs and cats had ceased to be objects of fear, and were become his greatest pets, and constant companions at table. (Tench 1979, 143)

Similarly, the colonists were acquiring knowledge of Arabanoo’s language and culture, which they would later use in dealing with other Aboriginal people:

One of our chief amusements, after the cloth was removed [that is, after dinner], was to make him repeat the names of things in his language, which he never hesitated to do with the utmost alacrity, correcting our pronunciation when erroneous. Much information relating to the customs and manners of his country was also gained from him. (Tench 1979, 143)

The colonists began to make use of the Aboriginal language they learned from Arabanoo. An early example is found in Hunter’s account of an expedition to Broken Bay on 6 June 1789. After pitching their tents for the night, at ‘Pitt-Water’, they found an Aboriginal woman hiding from them in the long wet grass, unable to run away because she was weak from what was thought to be smallpox:

She was discovered by some person who having fired at and shot a hawk from a tree right over her, terrified her so much that she cried out and discovered herself...we all went to see this unhappy girl...she appeared to be about 17 or 18 years of age, and had covered her debilitated and naked body with the wet grass, having no other means of hiding herself; she was very much frightened on our approaching her, and shed many tears, with piteous lamentations: we understood none of her expressions, but felt much concern at the distress she seemed to suffer. We endeavoured all in our power to make her easy, and with the assistance of a few expressions which had been collected from poor Ara-ba-noo while he was alive, we soothed her distress a little. (Hunter 1968, 96)

In spite of the knowledge gained from Arabanoo, Phillip’s experiment was regarded as a linguistic disappointment:

He did not want docility; but either from the difficulty of acquiring our language, from the unskilfulness of his teachers, or from some natural defect, his progress in learning it was not equal to what we had expected. (Tench 1979, 150)

Phillip’s hopes that Arabanoo would be their link with the Aboriginal population in general were finally dashed by his death on 18 May 1789 (Tench 1979, 149). Collins describes how Arabanoo cared for two Aboriginal children during what appeared to be a smallpox plague raging amongst the Aboriginal population. Arabanoo caught the disease and eventually succumbed:

From the first hour of the introduction of the boy and girl into the settlement, it was feared that the native who had been so instrumental in bringing them in, and whose attention to them during their illness excited the admiration of every one that witnessed it, would be attacked by the same disorder; as on his person were found none of those traces of its ravages which are frequently left behind. It happened as the fears of every one predicted; he fell a victim to the disease in eight days after he was seized with it, to the great regret of every one who had witnessed how little of the savage was found in his manner, and how quickly he was substituting in its place a docile, affable, and truly amiable deportment. (Collins 1975 vol 1, 54)

The girl (named Boorong or Abaroo) and the boy (Nanberry) continued to live with the colonists. But they were not considered old enough to be influential, nor competent enough in either English or an Aboriginal language to explain Phillip’s intentions to other Aboriginal people.

THE SECOND LINGUISTIC EXPERIMENT: BENNELONG’S COOPERATION

The ability to communicate fully with the Aborigines became an increasingly urgent concern for Phillip as attacks against lone colonists became frequent in 1789. Given the shyness of the Aborigines, official policy centred on training an Aboriginal captive to speak English:

The want of one of the people of this country, who, from a habit of living amongst us, might have been the means of preventing much of this hostile disposition in them towards us, was much to be lamented. If poor Ara-ba-noo had lived, he would have acquired enough of our language to have understood whatever we wished him to communicate to his countrymen; he could have made them perfectly understand, that we wished to live with them on the most friendly footing, and that we wished to promote, as much as might be in our power, their comfort and happiness. (Hunter 1968, 114)

On 25 November 1789 Phillip detained two more men, Colbee and Bennelong. Colbee escaped almost immediately but Bennelong was caught in the act of following him. He was shackled and guarded by a convict and subjected to language lessons. Bennelong was judged to be a much better language learner than Arabanoo and he rapidly acquired enough English to communicate with the colonists:

His powers of mind were certainly far above mediocrity. He acquired knowledge, both of our manners and language, faster than his predecessor had done. He willingly communicated information; sang, danced, and capered: told us all the customs of his country, and all the details of his family economy. (Tench 1979, 160)

He was described as an accomplished mimic:

He is a very intelligent man, and much information may, no doubt, be procured from him when he can be well understood... He is very good-natured, being seldom angry at any jokes that may be passed upon him, and he readily imitates all the actions and gestures of every person in the governor’s family. (Hunter 1968, 269)

As Tench mentions, he particularly liked imitating Phillip’s French cook:

...whom he had constantly made the butt of his ridicule, by mimicking his voice, gait, and other peculiarities, all of which he again went through with his wonted exactness and drollery. (Tench 1979, 178)

Tench (1979, 176) noted that Bennelong spoke ‘broken English’ which suggests that at least an incipient pidgin language had developed through the colonists’ communication with Arabanoo and then Bennelong.

Bennelong escaped from the settlement on 3 May 1790, returning many months later, but only after much enticing by Phillip. Bennelong was able to use his influence with both the Aboriginal people and the colonists to sustain interaction between the groups. Aboriginal people began to visit the settlement more often, and started to visit of their own accord unaccompanied by Bennelong. By November 1790, Tench was able to comment that:

With the natives we are hand and glove. They throng the camp every day, and sometimes by their clamour and importunity for bread and meat (of which they now all eat greedily) are become very troublesome. God knows, we have little enough for ourselves! (Tench 1979, 192)

The social situation created by the influx of Aboriginal people into Sydney was conducive to the development of a pidgin language (see chapter 10 by Harris). Textual evidence of pidgin is scanty but Collins remarks that a mixed language had developed in the colony as a result of the regular communication between Aboriginal people and colonists:

By slow degrees we began mutually to be pleased with, and to understand each other. Language, indeed, is out of the question; for at the time of writing this [September 1796] nothing but a barbarous mixture of English with the Port Jackson dialect is spoken by either party; and it must be added, that even in this the natives have the advantage, comprehending with much greater aptness than we can pretend to, every thing they hear us say. (Collins 1975 vol 1, 451)

Collins’s comments strongly suggest the emergence of a stable pidgin language. His observation that Aboriginal people were the most proficient speakers of the language suggests that they were also its principal creators. Collins also confessed himself to be a user of the mixed language. The ethnographic data he was able to collect using the language allowed him to make a detailed comparison of Christian beliefs and those of the Aboriginal people familiar to him (Collins 1975 vol 1, 454-55). The mixed language must have been quite stable and must have had a substantial lexicon for Collins to have been able to converse at the necessary level.

INFORMAL CONTACTS

The records which remain from the period of Phillip’s governorship are primarily official and there is little evidence of informal encounters between Aboriginal people and colonists aside from reports of attacks on convicts. Collins does report that within the first few days of settlement in a cove a ‘family’ of Aboriginal people was regularly visited:

...by large parties of the convicts of both sexes on those days in which they were not wanted for labour, where they danced and sang with apparent good humour. (Collins 1975 vol 1, 32)

Convicts formed the largest segment of the first colonial population and they were not overly confined. But their opportunities to mix with Aboriginal people were limited: they were compelled to work most of the day and they were subject to restrictions placed on them by Phillip. Phillip’s desire to keep Aboriginal people and convicts apart was, nevertheless, very difficult to enforce given the sheer numbers of convicts relative to the Marine guards. At the very least, some informal linguistic interaction must have been taking place.

EXPERIENCES OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE WITH THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

Both Aboriginal people and colonists had difficulty with each other’s languages:

But if they sometimes put us to difficulty, many of our words were to them unutterable. The letters s and v they never could pronounce: the latter became invariably w, and the former mocked all their efforts...and a more unfortunate defect in learning our language could not easily be pointed out. (Tench 1979, 293)

The S is a letter which they cannot pronounce, having no sound in their language similar to it. When bidden to pronounce sun, they always say tun; salt, talt; and so of all words wherein it occurs. (Tench 1979, 189)

Colonists acquired many Aboriginal words while interrogating Aboriginal people in their attempt to understand and describe their new country. Similarly, Aboriginal people interrogated colonists about their cultural artefacts and lifestyle. While colonists seem to have been content to use Aboriginal words for Aboriginal artefacts and many of the plants and animals new to them, Aboriginal people coined words from their own languages in addition to acquiring the English terms:

Their translation of our words into their language is always apposite, comprehensive, and drawn from images familiar to them: a gun, for instance, they call Gooroobeera, that is — a stick of fire. Sometimes also, by a licence of language, they call those who carry guns by the same name. But the appellation by which they generally distinguished us was that of Bereewolgal, meaning — men come from afar. (Tench 1979, 292)

The first time Colbee saw a monkey, he called Wùr-ra (a rat); but on examining its paws, he exclaimed, with astonishment and affright, Mùl-la (a man). (Tench 1979, 270)

Arabanoo died before he re-established extended communication with other Aboriginal people and cannot be regarded as having contributed significantly to the early acquisition of knowledge about English by Aboriginal people. Bennelong, on the other hand, returned to live with his people after several months of captivity amongst the colonists. It is well-attested in the literature of the period that he was a major catalyst in disseminating knowledge about the colony and its official language. One fragment of English that he taught other Aboriginal people was that ‘the King’ was said in connection with wine drinking:

A bottle was held up, and on his being asked what it was, in his own language, he answered, ‘the King’; for as he had always heard his Majesty’s health drank in the first glass after dinner at the governor’s table, and had been made to repeat the word before he drank his own glass of wine, he supposed the liquor was named ‘the King’; and though he afterwards knew it was called wine, yet he would frequently call it King. (Phillip 1789-91, 306-7)

Aborigines from Roma in Queensland still use ‘king’ as a generic for alcohol. (John Ward Watkins, personal communication)

OFFICERS OF THE MARINES AND ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES

Phillip strongly encouraged his officers to acquire an Aboriginal language and, most accounts of life in the colony written during Phillip’s governorship include at least a short vocabulary and some grammatical comment about the Aboriginal languages encountered in and around Sydney. The officers grappled with ways to pronounce and transcribe the sounds they heard:

Not only their combinations, but some of their simple sounds, were difficult of pronunciation to mouths purely English: diphthongs often occur: one of the most common is that of a e, or perhaps, a i, pronounced not unlike those letteres [sic] in the French verb hair, to hate. The letter y frequently follows d in the same syllable: thus the word which signifies a woman is Dyin; although the structure of our language requires us to spell it Dee-in. (Tench 1979, 292-93)

For two years it was believed that there was only one Aboriginal language in the Sydney region. This fallacy was exposed when Phillip, in April 1791, explored forty miles (about sixty-four kilometres) west of Sydney to the Hawkesbury and discovered a group of Aboriginal people with a language that was different to that of the Port Jackson people:

Though the tribe of Buruberongal, to which these men belonged, live chiefly by hunting, the women are employed in fishing, and our party were told that they caught large mullet in the river. Neither of these men had lost their front tooth, and the names they gave to several parts of the body were such as the natives about Sydney had never been heard to make use of. Ga-dia (the penis), they called Cudda; Go-rey (the ear), they called Ben-ne; in the word mi (the eye), they pronounced the letter I as an E. And in many other instances their pronunciation varied, so that there is good reason to believe several different languages are spoken by the natives of this country, and this accounts for only one or two of those words given in Captain Cook’s vocabulary having ever been heard amongst the natives who visited the settlement. (Phillip 1789-91, 347)

Several of the officers included in their published journals small comparative sets of vocabulary used by people and inland people, to indicate the differences. For example (Tench 1979, 231):

| English | Name on the sea coast | Name at the Hawkesbury |

|---|---|---|

| The Moon | Yèn-ee-da | Con-dò-en |

| The Ear | Goo-reè | Bèn-na |

| The Forehead | Nùl-lo | Nar-ràn |

| The Belly | Bar-an’ g | Bin’ -dee |

| The Navel | Mùn-ee-ro | Boom-bon’g |

| The Buttocks | Boong | Bay-leè |

| The Neck | Càl-ang | Gan-gà |

| The Thigh | Tàr-a | Dàr-a |

| The Hair | Deè-war-a | Keè-war-a |

WILLIAM DAWES AND HIS RESEARCHES

The richest source of information about a Sydney language is a collection of three small notebooks which are held in the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. The first notebook is catalogued as SOAS Manuscript MS.4165 (a), and it is titled Grammatical Forms of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney, by Dawes, in the Year 1790. It contains verb paradigms and some textual examples as well as a few comments on grammatical aspects of the language. The second manuscript, bound with the first and catalogued as SOAS Manuscript MS.4165(b), is titled Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales in the Neighbourhood of Sydney. Native and English, by Dawes. It begins with a table of the orthography chosen by Dawes for recording his data and is mainly a lexicon in roughly alphabetical order with longer and more numerous texts than in manuscript (a) and with further brief grammatical comments. Held with these notebooks is another notebook labelled SOAS Manuscript MS.4165 (c), titled Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney. (Native and English, but not Alphabetical). It is mostly a lexical set with a few texts and grammatical comments.

The authorship of this notebook remains controversial, but a comparison of the two hands in the manuscript with those of other First Fleeters, suggests that it is at least in part written by Governor Phillip himself. The rough hand matches that of Phillip’s rough hand exactly. Two First Fleet officers, David Collins and John Hunter, are also likely to have been contributors to the notebook. Evidence of their authorship is found in a comment by another officer, Philip Gidley King. King published a list of words in his journal, which he copied from a notebook used by Phillip, Hunter and Collins and lent to him by Collins. He wrote:

I shall now add a vocabulary of the language, which I procured from Mr. Collins and governor Phillip, both of whom had been very assiduous in procuring words to compose it...the following vocabulary, which Mr. Collins permitted my to copy...was much enlarged by Captain Hunter. (King 1968, 270)

The list copied by King is very similar to the list in the anonymous notebook and the orthography used is the same. Minor differences in the lists can be attributed to King who ‘rejected all doubtful words’ so that the list could be ‘depended upon to be correct’ (King 1968, 270). Within the notebooks there is no name given to the language nor is there a word for language, but the word for people is given in several places as Iora, a name now often given to the language of Sydney.

Lieutenant William Dawes was a well-travelled and well-educated man of twenty-six years when he came to Australia with the First Fleet as the colony’s astronomer at the suggestion of Joseph Banks. The other officers were also wellversed in the various humanitites and sciences of the eighteenth century, but Dawes:

...was the scholar of the expedition, man of letters and man of science, explorer, mapmaker, student of language, of anthropology, of astronomy, of botany, of surveying and of engineering, teacher and philanthropist. (Wood, quoted in McAfee 1981, 10)

Captain Watkin Tench testified to the excellence of Dawes’ research from which he had hoped to benefit in his own publication:

Of the language of New South Wales I once hoped to have subjoined to this work such an exposition, as should have attracted public notice; and have excited public esteem. But the abrupt departure of Mr Dawes, who, stimulated equally by curiosity and philanthropy, had hardly set foot on his native country, when he again quitted it, to encounter new perils, in the service of the Sierra Leona [sic] company, precludes me from executing this part of my original intention, in which he had promised to co-operate with me; and in which he had advanced his researches beyond the reach of competition. (Tench 1979, 291)

Dawes’s notebooks reveal more than the grammatical and lexical features of the language he was studying. They are also a record of his interactions with Aboriginal people in Sydney and particularly with a young woman called Patyegaráng (or Patye as he usually called her), who was probably Dawes’s main teacher. He included notes that demonstrate that he checked his queries about the language with her:

On saying to the two girls to try if they would correct me Ngyine, Gonagulye, ngia, Nangadyingun. Patye did correct me and said Bial Nangadyingun; Nangadyinye Hence Nangadyingun is Dual We, and Nangadyínye is Plural We. (Dawes 1790-91b)

There is also evidence within the Dawes manuscripts that he was teaching Patye English. He wrote of his chagrin at her shyness in displaying her reading skills:

Wúrul. Wúrulbadyaóu Bashful. I was ashamed. This was said to me by Patyegaráng after the departure of some strangers, before whom I could scarce prevail on her to read 2tthSeptr. 1791. (Dawes 1790-91b).

When Dawes asked Patye why she cooperated in his linguistic experiments, she frankly answered that he made her life easy:

Dawes: Minyin ngíni bial piabúni whiteman? Why don’t you (scorn to) speak like a whiteman? Patye: Mangabunínga bial. Not understanding this answer I asked her to explain it which she did very clearly, by giving me to understand it was because I gave her victuals, drink and every thing she wanted, without putting her to the trouble of asking for it. (Dawes 1790-91b)

Unfortunately, Dawes several times disobeyed orders given by Phillip (once in an attempt to mediate on behalf of the Aboriginal population) and was considered to be a hazard to discipline in the colony. His term of service was not renewed despite his desire to settle in New South Wales. He was sent home to England when Phillip was relieved in December 1791 and never returned to Australia.

LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE FOR LANGUAGE CONTACT IN SYDNEY

As noted above, the writings of First Fleeters contain some data that provide evidence for the development of contact language in Sydney. Data such as Dawes’ notes on the Sydney language are an invaluable record of one colonist’s attempts to grapple with the problems caused by the lack of a common language between himself and the Aboriginal people. His account of the Sydney language is excellent in its detail and fulsome enough to facilitate a reconstruction of the language by modern linguists (Osmond 1989; Troy 1992a; Wilkins forthcoming). However, within all the linguistic data and comments on language contact produced by the First Fleeters, there is enough evidence to suggest the early beginnings of New South Wales Pidgin (Troy 1990 and 1992a).

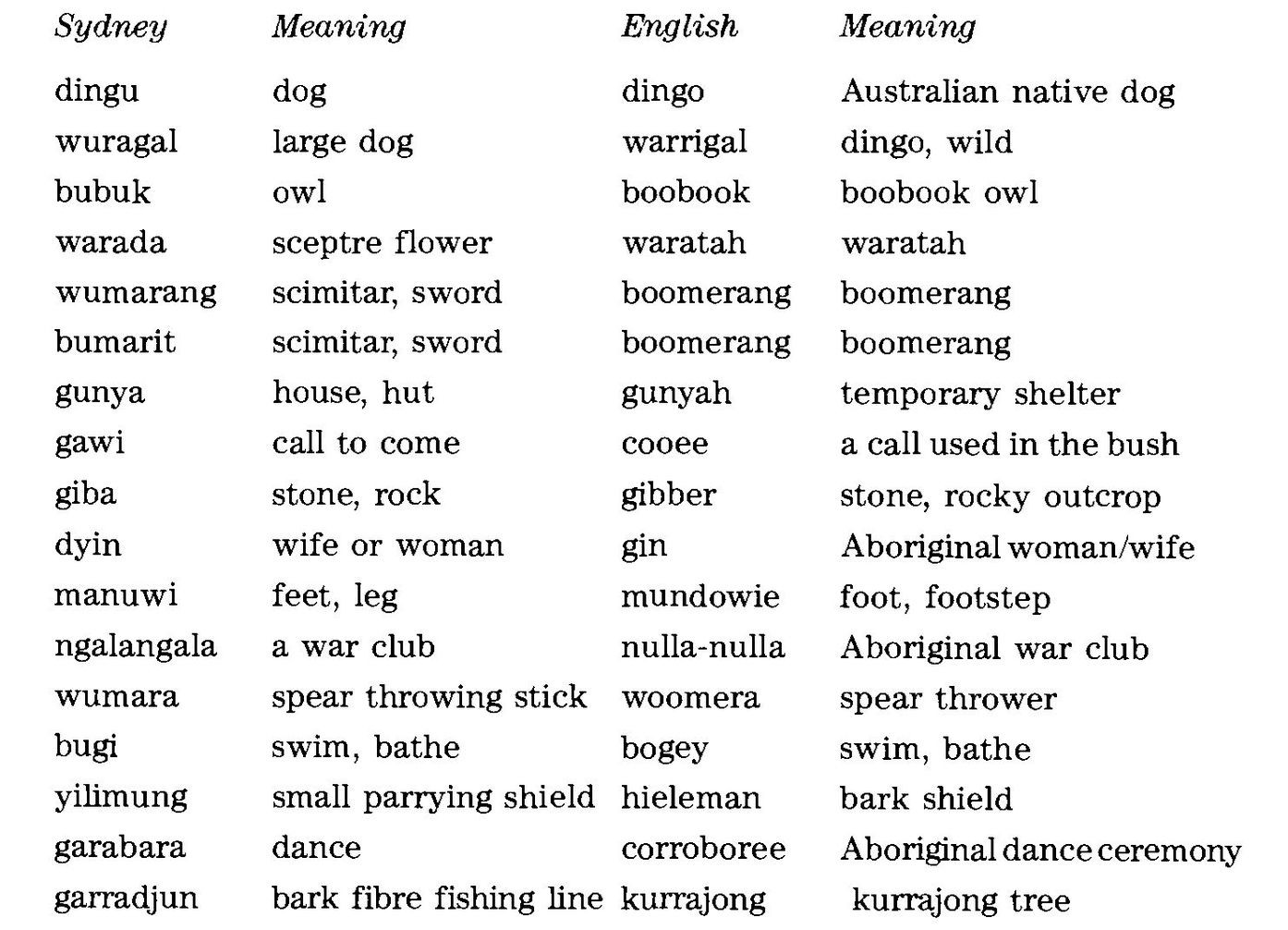

The early language contact provided Australian English with some of its core vocabulary. The following list contains words found in the Sydney language notebooks which are now used in Australian English and must have been very early borrowings. The words were also part of the core vocabulary of New South Wales Pidgin (Troy forthcoming).

The wumarang and bumarit were different kinds of sword-like weapons which could be used for fighting hand-to-hand or could be thrown (Troy 1992a). The Australian English word ‘boomerang’ is probably a combination of the two words which came into use in the early nineteeth century.

Aboriginal people borrowed words from English and coined new words in their own language to provide the new vocabulary needed to describe the colonists and their culture. The English words they borrowed were mostly for food and artefacts — biscuit, bread, breakfast, book, handkerchief, jacket, candle, potato, tea, sugar, window. They used both ‘whiteman’ and the Sydney language coinage barawalgal as words for the colonists. The following table lists the coinages that can be found in the Sydney language notebooks. Many of the borrowings and coinages also became part of New South Wales Pidgin.

| Coinage | Meaning | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| barawalgal | non-Aboriginal person | barawal ‘very far’, -gal ‘people’ |

| dalangyila | window glass | dalang ‘tongue’ |

| djarraba | musket | djarraba ‘fire stick, giver of fire’ |

| garadyigan | non-Aboriginal surgeon | garadyigan ‘healer, clever man, sorcerer’ |

| garani | biscuit | derivation unknown |

| garrangal | jacket | derivation unknown |

| gunya | house or hut | gunya ‘artificially constructed shelter’ |

| marri nuwi | the ship Sirius | marri ‘big’, nuwi ‘canoe’ |

| madyi | petticoat | derivation unknown |

| namuru | compass | na- ‘see’, maru ‘path’ |

| nananyila | reading glass | nana- ‘very see’ |

| nanyila | telescope | na- ‘see’ |

| narang nuwi | the ship Supply | narang ‘little’, nuwi ‘canoe’ |

| ngalawi | house | ngalawa- ‘sit’, -wi ‘them’ |

| ngunmal | palisade fence | derivation unknown |

| wanyuwa | horse | derivation unknown |

| wulgan | a pair of stays | derivation unknown |

CONCLUSION

During the governorship of Arthur Phillip permanent social relations between Aboriginal people and colonists were established. Phillip’s policy of developing communication between the indigenous and introduced populations of New South Wales provided the motivation for language contact. Although thwarted at first, Phillip persisted and subjected captive Aboriginal people to linguistic experiments. Eventually, through his own efforts and those of Bennelong, prolonged language contact was established. The settlement provided an environment in which a pidgin language could develop. It is well-established that a pidgin now known as New South Wales Pidgin had its origins in Sydney and was in regular use by the middle of the nineteenth century (Troy 1990). The beginnings of such a pidgin can be seen in the records of the First Fleet chroniclers.

FOR DISCUSSION

- How did communication begin between colonists and Aboriginal people in early colonial New South Wales?

- Who were the key people in the establishment of communication and why were they important?

- What languages were used for communication between Aboriginal people and colonists in Sydney and what was the product of contact between those languages?

- How did the social environment of early Sydney contribute to the development of contact language?

REFERENCES

| Anon | |

| nd | Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney. (Native and English, but not Alphabetical), School of Oriental and African Studies manuscript MS.4165 (c). |

| Barton, G. | |

| 1889 | History of New South Wales from the Records: Volume 1 — Governor Phillip, 1783—1789, Charles Potter, Sydney. |

| Collins, D. | |

| 1975 | An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc, of the Native Inhabitants of that Country by David Collins Late Judge-Advocate and Secretary of the Colony, 2 vols, vol 1 originally published 1798, vol 2 originally published 1802. Edited by Brian H. Fletcher, A.H. & A.W. Reed, Sydney. |

| Dawes, W. | |

| 1790— 91a | Grammatical Forms of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney, by — Dawes, in the Year 1790. School of Oriental and African Studies manuscript MS.4165 (a). |

| 1790— 91b | Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney. Native and English, by — Dawes. School of Oriental and African Studies manuscript MS.4165 (b). |

| George III | |

| 1787 | Instructions for our Trusty and Well-Beloved Arthur Phillip... Quoted in Barton 1889, 481—87. |

| Hunter, J. | |

| 1968 [1793] | An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea, 1787-1792, by Captain John Hunter, Commander H.M.S Sirius, with Further Accounts by Governor Arthur Phillip, Lieutenant P.G. King, and Lieutenant H.L. Ball. Edited by J. Bach, Angus and Robertson, Sydney. |

| King, P.G. | |

| 1968 | Lieutenant King’s Journal. In Hunter 1968, 196-298. |

| McAfee, R.J. | |

| 1981 | Dawes‘s Meteorological Journal, Department of Science and Technology, Bureau of Meteorology, Historical Note No 2, Australian Government Publishing Office, Canberra. |

| Osmond, M. | |

| 1989 | A Reconstruction of the Phonology, Morphology, and Syntax of the Sydney Language as Recorded in the Notebooks of William Dawes, term paper, Department of Linguistics, Australian National University. |

| Phillip, A. | |

| 1789- 1791 | Journal of Governor Phillip, Quoted in Hunter 1968, 299-375. |

| Tench, W. | |

| 1979 | Sydney’s First Four Years, Being a Reprint of A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay’ and ‘A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson’ by Captain Watkin Tench of the Marines, introduction and annotations by L.F. Fitzhardinge. Library of Australian History, Sydney. |

| Troy, J. | |

| 1990 | Australian Aboriginal Contact with the English Language in New South Wales; 1788—1845, Pacific Linguistics B-103, Canberra. |

| 1992a | The Syddney Language, J. Troy, Canberra. |

| 1992b | The Sydney Language Notebooks and Responses to Language Contract in Early Colonial NSW, Australian Journal of Linguistics 12, 145—70. |

| forth coming | Melakeuka: A History and Description of NSW Pidgin. |