CHAPTER 7

OUT-OF-THE-ORDINARY WAYS OF USING A LANGUAGE

REGISTERS

Australian Aborigines often speak fluently more than one Aboriginal language, more than one regional variety of the same Aboriginal language, and one or more varieties of English. If they live in a traditional community, they are also likely to have available different varieties of their own regional dialect, which they use for different purposes and with persons of different social categories. These speech varieties include forms of the language used with or about relatives with whom people maintain relations of respect or avoidance (for example, mothers-in-law and certain kinds of cousins); forms used with relatives with whom people maintain relations of jesting familiarity; forms used with very young children (‘baby talk’); forms learned by young men in the course of their initiation and used only in that context; and sign language, in which gestures made with the hands are used instead of spoken words.

The use of the same language in different varieties for different social purposes is perfectly familiar to speakers of English. Consider the difference between saying ‘Harry needs a car’ and ‘Mr Fanshaw requires an automobile’. A car is the same thing as an automobile, needing is the same thing as requiring, and — let us say — ‘Harry’ and ‘Mr Fanshaw’ refer to the same person. The difference is one of appropriateness in certain situations and with certain people. A term often used for speech varieties of this sort is ‘register’. Registers in English tend to be characterised by differences in vocabulary, as in the examples just given, and by differences in grammar and sometimes in pronunciation as well.

RESPECT REGISTERS

The term ‘register’ seems an appropriate one for spoken varieties of Aboriginal languages of the types mentioned above. The special ‘respect’ speech variety used by a man (in some parts of Australia) in talking about his mother-in-law, for example, is used only in certain situations and with persons of certain categories, and it differs from ‘ordinary’ speech largely in the use of different vocabulary items. So, for example, in the Uw-Oykangand language of southwestern Cape York Peninsula the ordinary term for ‘foot’ is ebmal, but a man speaking to a person who stands in the kinship relation of potential mother-in-law to him will refer to the foot as arrmbun. The respect register, the form of speech that makes use of the term arrmbun, for ‘foot’, is known in Uw-Oykangand as Olkel-Ilmbanhthi.

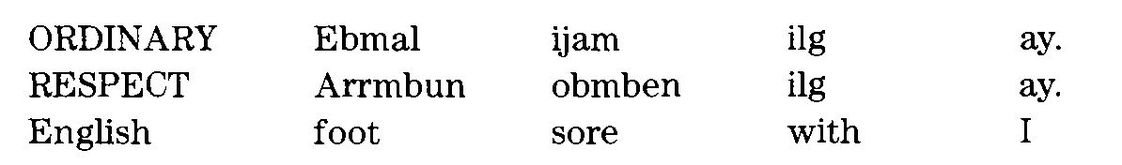

In explaining how whole sentences are put together in a respect register like Olkel-Ilmbanhthi, it is useful to distinguish between ‘content words’ and ‘function words’. This distinction can be made for any language. Content words in English include all the nouns, verbs, and adjectives while function words are conjunctions (‘and’, ‘or’, ‘but’, ‘if’, ‘when’, et cetera), prepositions (‘to’, ‘by’, ‘on’, et cetera) and pronouns (‘you’, ‘she’, ‘it’, ‘they’, et cetera). Function words tend to signal relationships among words and clauses and they are very limited in number though frequent in occurrence. In certain (but by no means all) Aboriginal languages, all of the content words in a proper respect register sentence belong to the respect vocabulary rather than the ordinary vocabulary. Uw-Oykangand is one such language. An example is the two ways to say ‘I have a sore foot’:

Here the respect-vocabulary word arrmbun ‘foot’ corresponds to the ordinary content word ebmal, a noun, and the respect-vocabulary word obmben, ‘sore’ corresponds to the content word ijam, an adjective (in Uw-Oykangand a kind of noun). But the function words ilg ‘with’ and ay ‘I’ remain the same in both ways of speaking.

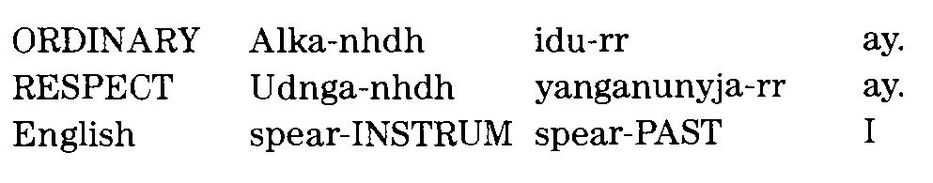

In a language like Uw-Oykangand (or English), the list of ‘function’ elements includes not only whole words, but also parts of words. Examples of such parts in Uw-Oykangand are the endings that signal the tense of verbs and those that signal the case of nouns. These are expressed with the same forms in respect-register speech as in ordinary speech, as the following examples, which mean ‘I speared it with a spear’, illustrate:

Here the content words for ‘spear’ (the nouns alka- and udnga-) and ‘to spear’ (the verbs idu- and yanganunyja-) differ from one register to the other, but the instrumental case-ending -nhdh (‘with’ a spear) and the past tense-ending -rr, like the function word ay ‘I’, remain constant.

Not all Aboriginal respect languages are as thorough as Olkel-Ilmbanhthi in replacing content words. For example, in the Yir-Yoront language — spoken by Uw-Oykangand’s neighbour to the northwest — inclusion of the function word wangal in a sentence, preceding the verb, characterises the sentence as respectful (wangal also occurs as a content word meaning ‘hand’ in the respect register). The Yir-Yoront respect register also makes use of special content words, but in nowhere near as consistent or thoroughgoing a way as Uw-Oykangand.

Respect-register vocabulary is in a sense an ‘add-on’ to the ordinary vocabulary of a language. It is created in a number of ways; some of these are more favoured in some regions than in others. There are, to start with, certain words which occur in the respect vocabularies of a number of not-very-closely related languages in a single region. For example, the Yir-Yoront respect word for ‘tree, stick’, yulh, is cognate with the respect word for ‘tree, stick’ in a number of languages spoken to the north. Then there are respect words derived from ordinary words on the basis of some trope: the ordinary Yir-Yoront word thorrchn means ‘hair’, and its derivative thorrchonh means ‘dog’ or ‘(hairy) yam’. Respect words can, for example, be derived from ordinary words: the Yir-Yoront respect word for ‘go’, larr-ma, is compounded of the ordinary words for ‘ground’, larr, and ‘tread on’, ma. And, in a number of regions, there is a practice of using certain ordinary words from a neighbouring dialect or language as respect words in one’s own.

Although the function words in Aboriginal respect registers are normally the same as those in the ordinary register, they are in certain cases used differently. One typical case is the pronouns for ‘you’. In ordinary Uw-Oykangand, ‘you’ (one person) is inang, ‘you two’ is ubal, and ‘you’ (more than two persons) is vrr. But in Olkel-Ilmbanhthi, any person or persons addressed, even if only one, are addressed with the plural pronoun urr. The use of the plural in respectful speech is a feature of many languages right across the world, with no historical connection to each other. Those readers who have studied French will recognise it in the different usage of the pronouns tu (singular) and vous (plural), both meaning ‘you’, but the latter used where respect or deference is intended.

Another common feature of respectful speech is a certain amount of intentional vagueness. It is as if the message of the utterance becomes to an extent less important than the nature of the social relationship that the speaker is trying to maintain or establish with the person spoken to. In the respect registers of Aboriginal languages such vagueness is implicit in the use of a single respect-register word to substitute for any of a number of ordinary-register words that are related to each other in one way or another. Most usually, this relation is one of membership in the same class based on similarity of meaning. It is as if, in English, there were a respect register in which the word ‘vehicle’ was always used whenever one wanted to refer to a car, a bus, or a truck. An Aboriginal respect register may, for example, refer to any of the different kinds of shark and stingray, each with its own name in the ordinary register, by a single term. It is still possible to be precise in a respect register. One can, if necessary, always use the respect word for ‘shark-or-ray’ and qualify it as, say, ‘the one with spots and a long tail’. It is rather that the normal purpose of respect register is not so much to make precise commentary as to negotiate difficult relationships.

Classifying things according to their family-like relations, or taxonomic class inclusion, is by no means the only principle on which Aboriginal respect registers use a single term as a substitute for more than one ordinary term. Olkel-Ilmbanhthi, for example, uses elngamb instead of ordinary Uw-Oykangand ew ‘mouth’ and ow ‘nose’ (perhaps because of their proximity on the face, but possibly also because of the phonetic similarity of the words), and unhunh for the ordinary words ef ‘tongue’ and ukan ‘grass’ (presumably having in mind the similarity in shape).

RESPECT VOCABULARY AND CLASSIFICATION

Where a respect register, like Olkel-Ilmbanhthi, has the feature that all content words must have a special equivalent word in the respect vocabulary, it is typically taxonomic class inclusion that is the major principle on which many ordinary-register words are equated with a single word in the respect register. Here the respect register becomes a handy means for investigating the taxonomic classes that a language recognises. People are sometimes rather vague about these things: is a bicycle a kind of vehicle? What about a train? An aeroplane? But in the relation between an ordinary vocabulary and a respect vocabulary with a replacement term for every content word, such questions have been answered, in a sense, in advance. The most extensively described language of this type is Dyirbal, spoken in the rainforest region of southeast Cape York Peninsula. Its respect register is known as Dyalnguy and its ordinary register as Guwal.

In studying the correspondence between Guwal and Dyalnguy, Dixon (1971) asked speakers of Dyirbal to do two things: first, for every ordinary (Guwal) word, he asked a speaker what its respect vocabulary (Dyalnguy) equivalent was. Usually, each Guwal word corresponded to just one Dyalnguy word, but often each Dyalnguy word corresponded to several Guwal words. Second, for each Dyalnguy word, he asked what its Guwal equivalent was. With great consistency, Dyirbal speakers cited not all of the corresponding Guwal words, but just one of them. For example, for each of the Guwal words buwanyu ‘tell’, jinkanyu ‘tell a particular piece of news’, gindimban ‘warn’, and ngarran ‘tell someone one does not have a certain thing, for example food, when one has’, the Dyalnguy equivalent is wuyuban. When asked what the ordinary word was for wuyuban, Dyirbal speakers answered that it was buwanyu, that is, ‘to tell’, purely and simply. So, not only do the correspondences of Guwal to Dyalnguy vocabulary amount to an objective form of evidence for speakers’ feelings about the similarities in meaning between words, but they suggest that some of these meanings are more fundamental than others. In Dixon’s terminology, verbs like buwanyu ‘tell’ are nuclear verbs, and the other ‘tell’ verbs, jinkanyu, gindimban, and ngarran, are non-nuclear verbs. On these taxonomic groups and on the nuclear/non-nuclear distinction, an extensive analysis of the meanings of Dyirbal words can be built.

THE NATURE OF RESPECT

The study of respect registers helps in the understanding of many other areas of Aboriginal life besides the meanings of words; one such area is that of the nature of respect itself, and of the particular social relations of which respect is a feature. Most Aboriginal languages have a respect register, but the particular relatives with whom, or about whom, one uses the respect register differ from one group to the next. In some groups, the relative is only the mother-in-law, or any person who is related in such a way as to be appropriate as a mother-in-law. In most Aboriginal groups, a woman and a man related as mother-in-law and son-in-law take great care never to be anywhere near each other; often the man will use respect register when he talks about his mother-in-law. In some communities a man is allowed to be in the presence of a potential mother-in-law (a woman to whose daughter he is neither married nor betrothed), but if he addresses her he will use respect register, and more usually he will speak to her using a third person as an intermediary. Sometimes this third person will just stand there and maintain the fiction of being an intermediary; sometimes the conversation is carried on through an imaginary third person. In various communities of Cape York, including the Yir-Yoront and the Wik-Ngathana community not far to the north, the list of relatives with whom one uses respect register is a longer one: a man speaking to (or sometimes about) his daughter, a man speaking with his wife’s brother or with his mother’s brother or with certain of his grandparents. The list and the details of how and when the respect register is used vary from one community to the next.

People can manipulate relationships by failing to use respect register where it is appropriate, or using it where it is not. Storytellers can create irony when they have a character use respect register but fail to follow through with other appropriate actions: so it is that a personage in a Yir-Yoront story who is notorious for his outrageous behaviour correctly addresses his mother-in-law’s father (a kind of grandfather) in respect register, informing his grandfather that he is keeping for himself the wallaby that the grandfather has killed. According to proper etiquette, he should be giving food to his grandfather rather than taking it from him.

INITIATION REGISTERS

The detailed study of the use of respect registers can reveal endless subtleties in social behaviour. But the Aboriginal repertoire of speech varieties is by no means limited to these. Another sort of register in Aboriginal languages that has received a great deal of attention from scholars is that which older men teach to younger men as part of their advanced initiation. Of these registers it can in general be said that they are brilliant creations in which a very small stock of special words is made to do all the work of framing any proposition that a speaker wants to express. Because details of initiation practices are sacred and are kept as secrets among initiated men, it is not in general ethical to discuss them in scholarly publications.

But in one case, that of the initiation register (known as Demin or Damin) of the Lardil people of Mornington Island in Queensland, the initiated men themselves have released details to the general public. They have done this because, on the one hand, they are no longer performing initiations — having been prevented from doing so in the past by the mission authorities in charge of their settlement — and, on the other hand, they feel that they have in Demin a creation worthy of the world’s admiration. Demin uses some 150 basic elements to substitute for all the words of regular Lardil. Demin words differ from those of ordinary Lardil in one very conspicuous way: the sound-system according to which they are pronounced is radically unlike that of ordinary Lardil or of any other Australian Aboriginal language. This system includes in its inventory of sounds several nasalised clicks and an ingressive lateral (an [1] sound made by drawing the breath into the lungs). Without going into the details of how all these sounds are produced, it should nonetheless be clear to readers that words in Demin have and are intended to have a bizarre sound. Speakers find them both funny and fun to make.

The extremely small number of basic elements in Demin forces speakers to make very judicious use of them in allocating them to the various concepts expressed by single words in ordinary Lardil. It also forces speakers to draw extensively on their knowledge of complex sentence constructions in Lardil, in order to express distinctions at a level of fineness not possible by naming a thing with a single basic element. It seems also that there is in Demin no use of overgeneral reference to things to produce a deferential mode of speech. Rather, what seems to be asked of the young initiands is that they demonstrate verbal proficiency, just as they are asked to demonstrate proficiency in other aspects of adult life. In Lardil tradition, the invention of Demin is ascribed to a single person, Kalthad (or Yellow Trevally, as he would be known in English). Here, there is no mistaking the linkage of Demin with exceptional personal competence.

SIGN LANGUAGE

A phenomenon of a rather different kind from the spoken registers is sign language. Not a register, it is a different medium of communication — in somewhat the same sense as written language is. In sign language, the ‘words’ are hand motions. For example, the sign in the Warlpiri language (north-central Northern Territory) for ‘old man’ is the hand with fingers spread apart but slightly flexed, held with palm towards the face and moved a short distance forwards and back; the corresponding spoken word is purlka. Sign language is used by various persons in various situations, although some of the situations in which it might be thought to be most useful, such as between men who must be quiet while they are stalking game, are not in fact the occasions when it is most highly developed. The most highly elaborated sign language is used by mature women in Aboriginal communities where a woman, upon the death of her husband, must avoid speaking during an extended period of mourning. In these communities, most of which are located in the north-central desert region of the Northern Territory., mature women become proficient enough in sign language to express anything that can be expressed in the spoken language.

Any number of features of sign language are worthy of extensive discussion; here it will have to suffice to mention just three. The first is that a highly developed sign language like that of the Warlpiri is modelled closely on the spoken language, with signs corresponding to all the content words and also to some of the function words and affixes. There is little one-to-many correspondence of sign language words to spoken words; sign language is specific.

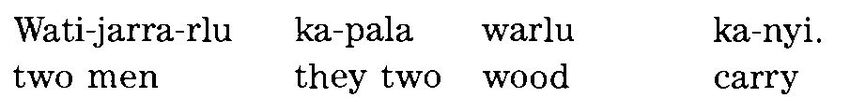

The second feature is that sign language omits signs for elements of the spoken language that indicate the grammatical relation of the parts of a sentence (who did what to whom) and the relative time at which the action is said to have occurred (the tense of the verbs). So, for example, the spoken Warlpiri sentence that means ‘two men are carrying firewood’ is:

where the ergative suffix -rlu signals that the men are the agents of the action, the auxiliary element kapala signals that the time is the present and that the subject of the sentence is dual, and the suffix -nyi signals that the time of the action is not in the past. The same sentence rendered in sign language contains the signs for ‘men’, ‘two’, ‘(fire)wood’, and ‘carry’, in that order, and omits the rest.

The third feature is that sign language ‘words’, when they are extended to cover the meanings of more than one spoken word, sometimes do so, not on the basis of shared features of meaning, but on the basis of shared features of sound. So, for example, the Warlpiri sign corresponding to the spoken word winpiri ‘spearwood’ (a species of tree) is used also for the spoken words wina ‘winner’, wiki ‘week’, wiki ‘whisky’, Winjiyi ‘Wednesday’, and Winiyi ‘Winnie’. The basis for the association is the shared syllable wi. It is of interest here that the first languages ever to be written, Sumerian and Egyptian, some 5,000 years ago, used signs which were pictures of what they represented but which also represented words that sounded similar. In so doing the writers of these languages made the first steps towards a representation of the sounds of language rather than of the meaningful units as wholes. Aboriginal sign language is a linguistic medium, and it appears to be evolving along similar lines to that other non-spoken medium, writing.

CONCLUSION

This discussion of non-ordinary forms of Aboriginal languages has, of course, barely scratched the surface. Much more can be said about each of the language varieties considered above, and numerous other varieties have not been mentioned at all. What is worth mentioning in closing is that all of these forms of communication represent not just intricate patterns of communication and social interaction, but intellectual achievements that involve conscious creative acts by their users.

FURTHER READING

Much of the information in this chapter comes from the readings mentioned below. Those who are interested in further study of this subject might wish to begin by consulting them.

The notion of ‘register’ is explained in Halliday and Hasan (1976). Interesting explorations of the subtleties of respect registers are contained in the articles by McConvell, Merlan, Rumsey and Sutton in Heath, Merlan, and Rumsey (1982). In the same collection is an introduction by Kenneth Hale to the initiation register of Lardil. The Dyirbal respect register is discussed in Dixon (1971). A discussion of the Yir-Yoront respect vocabulary and of the various origins of the words in it can be found in Alpher (1991). An excellent and thorough discussion of Aboriginal sign language is Kendon (1988).

FOR DISCUSSION

- Consider some examples of what would count as respectful or disrespectful utterances in English. Try to relate such examples to real situations and avoid artificially elaborate utterances that are unlikely to be genuinely used (such as ‘I wonder whether you would graciously consent to lending me a dollar’). You might consider such situations as writing a letter to apply for a job or introducing yourself to a new neighbour or to a new colleague at work, or speaking to someone who has just been to a funeral.

- Why do you think many languages use a plural ‘you’ to show respect? What other ways are there of avoiding a direct ‘you’? In Parliament, for example, it is conventional to speak of ‘the member for Southtown’ rather than to address the person directly: can you add other examples of this kind?

- How would you set about designing a sign language? How would you represent words like ‘true’ and ‘honest’? How, if at all, could you distinguish between ‘fall’ and ‘fell’ or between ‘tomorrow’ and ‘today’?

REFERENCES

| Alpher, B. | |

| 1991 | Yir-Yoront Lexicon: Sketch and Dictionary of an Australian Language, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin. |

| Dixon, R.M.W. | |

| 1971 | A Method of Semantic Description. In D.D. Steinberg and L.A. Jakobovits (eds), Semantics: An Interdisciplinary Reader in Philosophy, Linguistics and Psychology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. |

| Hale, K. | |

| 1982 | The Logic of Damin Kinship Terminology. In J. Heath, F. Merlan, and A. Rumsey (eds), Languages of Kinship in Aboriginal Australia, Oceania Linguistic Monographs 24, University of Sydney, Sydney, 31-37. |

| Halliday, M.A.K. and R. Hasan | |

| 1976 | Cohesion in English, Longman, London. |

| Haviland, J.B. | |

| 1979a | Guugu-Yimidhirr Brother-in-Law Language, Language in Society 8,365-93. |

| 1979b | How to Talk to Your Brother-in-Law in Guugu-Yimidhirr. In T. Shopen (ed), Languages and Their Speakers, Winthrop, Cambridge MA, 160-239. |

| Kendon, A. | |

| 1988 | Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. |

| McConvell, P. | |

| 1982 | Neutralisation and Degrees of Respect in Gurindji. In J. Heath, F. Merlan, and A. Rumsey (eds), Languages of Kinship in Aboriginal AustraLia, Oceania Linguistic Monographs 24, University of Sydney, Sydney, 86-106. |

| Merlan, F. | |

| 1982 | ‘Egocentric’ and ‘Altercentric’ Usage of Kin Terms in Mangarayi. In J. Heath, F. Merlan, and A. Rumsey (eds), Languages of Kinship in Aboriginal Australia, Oceania Linguistic Monographs 24, University of Sydney, Sydney, 107-24. |

| Rumsey, A. | |

| 1982 | Gun-Gunma: An Aboriginal Avoidance Language and Its Social Functions. In J. Heath, F. Merlan, and A. Rumsey (eds), Languages of Kinship in Aboriginal Australia, Oceania Linguistic Monographs 24, University of Sydney, Sydney, 160-81. |

| Sutton, P. | |

| 1982 | Personal Power, Kin Classification and Speech Etiquette in Aboriginal Australia. In J. Heath, F. Merlan, and A. Rumsey (eds), Languages of Kinship in Aboriginal Australia, Oceania Linguistic Monographs 24, University of Sydney, Sydney, 182-200. |