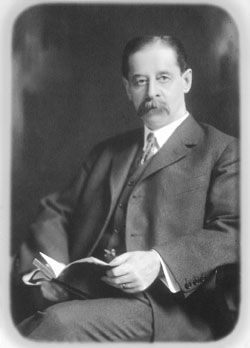

Edwin Atkins Grozier, editor and publisher of The Boston Post.

Mary Grozier

CHAPTER THREE

“NEWSPAPER GENIUS”

Like Ponzi, Richard Grozier was a bright, handsome young man with a taste for fine clothes. Also like Ponzi, he was approaching the midpoint of his life with little to show for himself. Unlike Ponzi, however, Grozier had every possible advantage—he was descended from Mayflower Pilgrims and had spent his life bathed in wealth and privilege.

Yet in 1917 Grozier was thirty years old, single, and living in his parents’ house. He worked, without distinction, for his father’s company after nearly flunking out of college and washing out of law school. As the only male heir, Grozier was destined to inherit his family’s business and the money and power that went with it. But it looked as though his inheritance would drop in value the moment he took possession.

Richard’s father was Edwin Atkins Grozier, editor, publisher, and owner of the Boston Post, the largest-circulation newspaper in Boston and one of the largest in the nation. Through relentless work and rare gifts, Edwin Grozier had engineered the Post’s rise from the brink of bankruptcy to the top of the pig pile of Boston newspapers. By the time he was Richard’s age, Edwin had already been one of the most respected newspapermen in the country. Without him, the Post would have been long dead, cannibalized by competitors on Newspaper Row.

Some thought the paper might still end up that way, once it passed to his son.

The first edition of Boston’s Daily Morning Post hit the streets November 9, 1831, under the ownership and editorial direction of Colonel Charles G. Greene, whose military title was honorary but whose journalism was sound. The Post appeared at a time when Boston newspapers seemed to be opening and closing every few months; fifteen printed their first and last editions between 1830 and 1840. But under Greene’s steady hand, the Post survived and grew steadily for four decades, establishing itself as a well-written, reliable Democratic voice in an age of partisan newspapers.

Then came November 9, 1872. A fast-moving fire consumed an empty hoopskirt factory on the edge of Boston’s financial district, then leapt from one building to the next. Many of the horses that were used to pull the city’s fire equipment had recently succumbed to an equine epidemic, so the Great Boston Fire burned for more than two days, consuming 776 buildings and leveling sixty-five acres downtown. The City upon a Hill was a smoldering ruin. Sullenly surveying the damage, Oliver Wendell Holmes was moved to verse: “On roof and wall, on dome and spire, flashed the false jewels of the fire.” The Post’s offices escaped the flames, but the oceans of water used to protect it ruined almost everything inside. Greene and his son, Nathaniel, reopened the paper in a new location, but it was never the same. When the nation fell into economic depression during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, the Greenes decided to sell.

The eager buyer was the Reverend Ezra D. Winslow, a Methodist minister, staunch prohibitionist, and member of the state Senate. He was also a forger and a swindler. In a scheme that would anticipate stock manipulators of a later day, Winslow sold twice as many shares of the Boston Post Company as allowed by the incorporating papers. He also forged the signatures of more than a dozen prominent men on banknotes for nearly a half million dollars, and pocketed thousands more loaned to him. He exchanged much of his stolen cash for gold, fled to Holland, and by some accounts ended up in Argentina, enjoying his ill-gotten gains in Buenos Aires and working as a reporter for a local newspaper.

The story of Winslow’s scam became part of Post lore, passed down year after year, deeply ingrained in the memories of its employees. Winslow had ruined the finances and shattered the credibility of the once-proud newspaper. For the next fifteen years the Post floundered under transient ownership. By 1891 it was hobbling along with fewer than three thousand subscribers. It had an antiquated printing plant, only a handful of advertisers, and a debt of $150,000. But where creditors saw a newspaper in its death throes, Edwin Grozier saw the opportunity of a lifetime.

Edwin Grozier was born September 12, 1859, aboard a clipper ship within sight of the Golden Gate in San Francisco harbor. It was a fitting arrival; Grozier men were storied mariners, and the ship’s master was Edwin’s father, Joshua, who routinely captained voyages from Boston around Cape Horn to California and back. When Edwin was six, his parents brought him and his two brothers to live on the far tip of Cape Cod, in Provincetown, the home of generations of sea captains and their families.

A sickly boy and an avid reader who dreamed of becoming a poet or a novelist, Edwin Grozier attended public schools and graduated from high school at age fifteen. In keeping with family tradition, and to improve his health, he spent the next two years sailing around the world. The teenage wanderer wrote detailed descriptions of the exotic ports he visited and sent them to Greene’s Boston Post, which was impressed enough to publish them as a series. In 1877, he returned home, spent some time at prep school, then entered Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. After a year he transferred to Boston University, drawn to Boston by the lure of Newspaper Row.

After graduating he landed a job at the Boston Globe, where he worked under the tutelage of the editor and publisher, General Charles H. Taylor, a gregarious Civil War veteran. Grozier was paid ten dollars a week, which he at first considered an enormous sum. Then his ambition took hold. “It was soon raised to twelve, to fifteen, to eighteen dollars,” he recalled. “I wanted more money—because I needed it!” Despite his fondness for Taylor, an offer of twenty-five dollars a week sent Grozier across Newspaper Row to the Boston Herald to cover politics. He distinguished himself quickly, in part because he was able to accurately record the long-winded speeches of the day with his uncommon skill at shorthand. During the 1883 campaign for Massachusetts governor, Grozier so impressed the Republican candidate, George D. Robinson, that as soon as Robinson was elected he hired the young reporter as his personal secretary.

But the pull of newspapering was strong. Eighteen months later, Grozier moved to New York and became personal secretary to Joseph Pulitzer, the Hungarian-born editor of the New York World and a journalism legend in the making. Pulitzer pioneered a formula of compelling human-interest stories, social justice crusades, and sensational battles with William Randolph Hearst and the New York Journal. Under Pulitzer, the World became the most profitable and most copied newspaper in the nation. Edwin Grozier had a front-row seat, and he was in thrall to Pulitzer: “I never saw anyone to equal him. His mind was like a flash of lightning, illuminating the dark places.”

For six exhausting years, Edwin Grozier routinely worked eighteen- and twenty-hour days learning the newspaper business top to bottom. Pulitzer recognized and rewarded Grozier’s brains and drive with some of the most difficult jobs in New York newspapers. By twenty-eight, Grozier was city editor of the World, and six months later he was editor in chief and business manager of the Evening World and the Sunday World. He did so well boosting circulation that Pulitzer once handed him a bonus of one thousand dollars in gold coins. But Grozier wanted to captain his own ship. His fondest wish was to buy a newspaper in New York, but he did not want to break his bond with Pulitzer by competing against the World.

While vacationing in Boston in 1891, Grozier heard from friends that the Post was on the verge of collapse. It was everything he wanted, in a city he knew and loved, and just right for his meager price range. First, he sought out the Globe’s Taylor, who was second only to Pulitzer as a newspaper mentor. Grozier came to Taylor’s office seeking absolution.

“If you have even the slightest objection, General,” Grozier told him, “I won’t consider purchasing the paper.”

Taylor placed a hand on Grozier’s shoulder. “Go ahead, Mr. Grozier. I don’t mind in the least.” Smiling, Taylor added, “If you can gather up any of the crumbs that fall from the Globe’s table, you’re welcome to them.”

“Thank you, General,” Grozier replied. “But I want to warn you that I shan’t be satisfied with crumbs. If I can, I shall go after the cake, too!”

At first, even crumbs would have seemed a feast. Boston was crowded with newspapers. In addition to the Post and Globe, there were the Daily Advertiser, the Evening Record, the Herald, the Journal, the Telegraph, the Transcript, and the Traveler. Soon the Boston American would join the scene. While the Post had hemorrhaged money and readers, its competitors had grown entrenched with various constituencies—the Brahmins who ruled the city relied on the Transcript, for instance.

Grozier was in danger of folding almost from the first edition. To purchase the paper, he had exhausted his life savings and plunged deep into debt. When he took the keys to the Post’s tired offices he was left with only one hundred dollars in cash. In the meantime, the thirty-two-year-old newspaper owner had a growing family to feed. In 1885, while working for Pulitzer, he had married Alice Goodell, the daughter of a prominent Salem, Massachusetts couple. When they returned from New York to Boston they had a four-year-old son and a two-year-old daughter.

In the days of larger-than-life newspapermen, Edwin Grozier seemed physically unfit for the job. One day, a young leather worker walked upstairs to the publisher’s second-floor office overlooking Washington Street. The leather worker stepped inside, hoping to be hired as a reporter despite his complete lack of qualifications for the job. He immediately thought he had entered the wrong office. He found the editor and publisher of the Post to be “a small, brownish man who sat at a large desk . . . just another undersized party, rather delicate and plaintive-looking, perhaps because he wore a straggly moustache, had a rug over his knees, and peered benevolently at me over the tops of his glasses.” The job applicant also might have noted that Grozier had close-set eyes, curtained by heavy lids.

Yet Grozier would not have minded the unflattering description; he was modest by nature and had no interest in provoking awe, particularly among the reporters he sent scouring the city for scoops. Something about the young man appealed to Grozier, and he offered him a job at eighteen dollars a week. It was the start of a remarkable writing career for Kenneth Roberts, who became a star at the Post and the best-selling author of the historical novels Arundel and Northwest Passage.

Edwin Grozier compensated for his lack of physical presence with what Roberts called “newspaper genius.” From the moment he took control of the paper, Grozier operated under a few guiding principles he once articulated: “Of first importance is the securing of the confidence, respect, and affection of your readers—by deserving them. Study the census. Know your field. Build scientifically. Print a little better newspaper than you think the public wants. Do not try to rise by pulling your contemporaries down. Attend to your own business. Do not believe your kind friends if they assure you that you are a genius. But work, work, work.”

He issued a public call to arms in his debut editorial: “By performance rather than promise the new Post seeks to be judged. By deed rather than words its record will be made.” He declared that the Post “aspires to guard the public interests, to be a bulwark against political corruption, an ally of justice and a scourge to crime; to defend the oppressed, to help the poor, to further the still grander development of the glorious civilization of New England.”

Grand sentiments were one thing, but Grozier knew he had to meet a payroll and the demands of creditors. His first actions on those fronts were counterintuitive: He dropped the paper’s price from three cents to a penny—a technique he had learned from Pulitzer to boost circulation—and lowered the cost of advertising. He also called a meeting of his creditors and asked their forbearance; he would pay them in full, he promised, but he needed time and more credit to keep afloat. Impressed by his sincerity, and hoping to avoid the pennies-on-the-dollar payoff that would result from Grozier’s failure, the creditors agreed. Still, the early years remained lean, and paydays were sometimes anxious. Grozier never missed a payroll, but more than once his staff gathered at the cashier’s window waiting to be paid from last-minute advertising receipts and the pennies turned in by newsboys. Sometimes even that was not enough, and Grozier borrowed to pay his staff.

“Most of the time, figuratively speaking, there was an ‘angel’ in one room and the sheriff in another,” Grozier once recalled. “An angel, you know, is someone who may possibly put up money to back you. But I was generally much more certain of the sheriff than I was of the angel.” What he needed most were readers, lots of them, so he tapped the techniques he had learned from Pulitzer and added new flavors all his own. Soon they paid off handsomely.

To capture public interest and build circulation, Grozier was not above employing carnival tactics, organizing a stream of inspired and slightly wacky promotions. He heard that an Englishman and his wife wanted to rid themselves of three trained elephants named Mollie, Waddy, and Tony. Grozier thought they would make ideal residents at the city’s Franklin Park Zoo. He was making enough money by this point that he could have paid for them himself and reaped all sorts of praise, but instead the Post called upon the children of Boston to become part owners of the pachyderms. The newspaper began collecting contributions toward the $15,000 purchase price. Grozier promised to print the names of every one of the contributors, even those who could spare only a cent or two. Thousands of children responded, and seventy thousand people turned out to welcome the elephants at a ceremony in Fenway Park, built two years earlier by the Globe’s Taylor as the new home of the Red Sox. From a simple profit-loss standpoint, it was a disaster. It cost the Post thirty cents, based on its advertising rate, to print the name of a child who had contributed a penny, and the newspaper still had to cough up several thousand dollars to close the deal. But Grozier knew it was a huge success.

“Every child who had given even one cent wanted to see his name in the paper, and was thrilled by the thought that he owned part of an elephant,” Grozier told a reporter. “Of course, it added thousands to the circulation of the Post, but it was a gain that was based not on appealing to the worst elements in human nature but to the best: to civic pride, to generosity, to interest in animals, to the affection of parents for their children. And so it helped us to win liking and affection.”

Later, the Post announced a giveaway of a free car for the best human-interest story: A FORD A DAY GIVEN AWAY! the paper screamed. Thousands of suggestions poured in, and scores of Model T’s were delivered. The paper printed photos of women only from the neck down, then offered ten dollars in gold to any woman who could identify herself and prove it by wearing the same outfit to the Post offices. They came in droves, and thousands more grabbed the paper each day hoping to recognize their headless selves. Another time, Grozier hired a movie scout named Bijou Fernandez to search for girls who wanted to be in the movies. Fernandez would spot a pretty girl in a small town and a Post reporter would write a story that would be printed alongside the girl’s picture. Circulation shot up by ten thousand the first week, though actual movie offers were scarce. Tapping into the same vein, the paper ran a feature called “The Prettiest Women in History,” featuring luminaries including Cleopatra and Helen of Troy.

Barely a day went by without some kind of promotion or gimmick. Once, Grozier announced that he was sending a reporter incognito to a certain part of the city. The paper would give one hundred dollars in cash to the first person who spoke these words to the reporter: “Good morning, have you read the Post today?” Suddenly those were the first words out of Bostonians’ mouths whenever they happened upon a stranger.

Then there was the “primitive man” stunt. The Post sent a man named Joe Knowles into the Maine woods, naked and empty-handed, to live completely alone for sixty days. During the two-month adventure, the paper printed dispatches and drawings Knowles made with charcoal on birch bark and left at a prearranged drop point. When Knowles emerged from the woods, wearing deer skins and carrying the tools of a caveman, some 400,000 people crammed the length of Washington Street to greet him. The paper’s circulation doubled that year.

When Grozier learned that letters addressed to Santa Claus were dumped in the dead-letter office, he began thinking about the unmet needs of the city’s poor children. He created the Post Santa Claus Fund to raise and distribute money and toys to Boston’s needy during the holidays. Grozier measured the fund’s success less by the number of newspapers it sold than by the number of toys it handed out. His soft spot for children showed just as clearly when the Post received letters about lost pets. “I see that this little girl has lost her dog,” he told a young editor one day. The editor knew what was coming next: “Do you think one of our men could find it for her?” A reporter was quickly dispatched.

The most enduring promotion was Grozier’s 1909 brainstorm to honor the oldest man in every town in the Post’s circulation area. He imported hundreds of the finest ebony canes from Africa and fitted them with polished fourteen-karat-gold heads, on which was inscribed: “Presented by The Boston Post to the oldest citizen of,” followed by the name of the resident’s town. Below that, to make clear that the cane should pass to the next oldest man upon the holder’s death, were the words “To be transmitted.” Grozier wrote to selectmen throughout much of New England asking them to locate the deserving recipients and present the canes, then inform the Post of the selection, ideally with a photo. Eventually, 431 canes were handed out, often with great pomp and ceremony followed by fawning stories in the Post. Holders of the canes variously attributed their longevity to abstinence from, or daily devotion to, alcohol and tobacco. The death of a Post cane holder was cause for another story, as was the token’s passage to the town’s next oldest man. To Grozier, the appeal was obvious: “In many small towns and villages the general store was a place where many men gathered to talk and swap stories. One of the most conspicuous figures in the group was the ‘oldest man.’ Age is a subject of universal interest, no matter whether it is among city folks or country folks. A man who has succeeded in cheating death longer than most of us manage to do it is always an interesting figure.”

Edwin Grozier knew he needed more than fun and games to win readers. He loved a good murder case. Lizzie Borden’s father and stepmother turned up dead less than a year after he bought the Post, and the early years of the new century provided an endless stream of other celebrated killings. Circulation always rose when murders involved the rich, the pious, an attractive woman, or a spurned lover. A case involving a minister with two beautiful young fiancées, one of whom turned up dead from poison in what looked like suicide, kept Grozier in gravy for weeks. A Post reporter cracked the case when he tracked down the minister’s purchase of cyanide. A close second was when a diver hired by Grozier found the severed head of a beautiful showgirl at the bottom of Boston Harbor. “Missing Head Found by the Post’s Diver,” the headline blared.

When not covering crime, the paper kept its promise to be a friend to the little guy. Grozier supported the labor movement and shorter work weeks, and fought for lower gas and telephone rates. The paper leaned to the Democratic Party, and Grozier worked to stay in touch with the needs of the common man. It was an approach he had pioneered in New York: “I used to go over among the swarming millions of the East and the West sides of the city; because it was there that we must build up our circulation if it was to be a large one; there, among the masses, not in the narrow strip of millionaires along Fifth Avenue.” In Boston, Grozier was a careful reader of the census, and he recognized that Boston’s surging Irish population would support the Irish nationalist movement. The Post was the first prominent American paper to show solidarity with Sinn Fein, and Grozier personally made large contributions to the nationalist cause.

At a time when “No Irish Need Apply” remained the practice in certain Brahmin quarters, Grozier supported the candidacy of David I. Walsh in his successful effort to become Massachusetts’ first Irish Catholic governor. Grozier further ingratiated the Post with Irish Bostonians by treating interviews with the city’s Catholic cardinal as front-page news.

Though Grozier calculated his positions carefully in terms of circulation, he also took unpopular positions based on his sense of fairness. Boston’s Irish and blacks were often at odds, competing for scarce resources, but the Post refused to favor one group over the other. William Monroe Trotter, editor of the Boston Guardian, a black newspaper, once said that Grozier ran his newspaper under a policy of “identical justice, freedom, and civil rights for all, regardless of race, creed, or color.”

The combination of aggressive news coverage, community appeal, and dedication to fair play, along with a healthy dose of razzle-dazzle, worked beyond all expectations. In time, Edwin Grozier’s Post outsold the Globe. And in a much smaller city, its circulation exceeded that of Pulitzer’s New York World. But the Post’s status as Boston’s premier newspaper would soon be tested as never before.