The California condor is one of the biggest birds in North America, weighing up to twenty-six pounds and standing nearly a yard tall, with a wingspan of nine and a half feet. As a child, I knew only about the vultures of Africa and Asia, for they frequently figured in my storybooks—usually in a somewhat sinister role as they patiently watched the hero, close to giving up as he struggled across the desert, thirsty and wounded. But one look at their hooked beaks, sharp talons, and cold greedy eyes, and he would summon the strength to reach safety. During my years in Africa, I have spent many hours watching the fascinating behavior of those vultures in the wild, but the California condor, which I learned about much later, I have seen only in captivity.

Initially, I was not attracted by its appearance. The bare skin of the head is so—well—bare! And its redness is the color of a boiled lobster. Truly, the condor is one of nature’s odd experiments, where so much of the poetry, so much of the magic, went into the fashioning of those glorious wings and stunning power of flight. Yet not quite all—for in photos of condors in the wild I’ve come to appreciate their splendid red skin standing out against jet-black feathers, glowing in the sunlight. And gradually, their faces have grown on me, slightly comical, endearing.

At one time, California condors ranged widely—from Baja California in Mexico all the way up the West Coast to British Columbia in Canada—but by the 1940s, they had disappeared almost everywhere, except for an estimated 150 in the arid canyons of Southern California. In 1974, there were reports of two condors in Baja California, and my late husband, Hugo van Lawick, was asked to fly down to try to film them. But the expedition never materialized, and the birds disappeared.

The decline in condor numbers was due to many factors, such as the number of people moving into the western United States, shooting by poachers and collectors, feeding on poisoned baits set out for bears, wolves, and coyotes by ranchers, and, perhaps most importantly, the unintentional poisoning from lead ammunition fragments in the carcasses and gut piles of animals shot by hunters.

A group of biologists decided that something must be done. True, an area of wilderness had been set aside for the condors, but it was not enough. It served to protect them when they were nesting—and it was a preferred place for that—but when they foraged, they would fly a hundred miles or so into the ranchlands, where there was no protection at all. Noel Snyder, a biologist and passionate advocate for the birds, helped to establish the Condor Recovery Program and subsequently led the condor research effort. Biologists sought to discover all they could about condor behavior and the causes for the decline in numbers, while at the same time planning a captive breeding facility so that additional birds would become available to boost the wild population.

But there were many people vehemently opposed to any kind of intervention, and a controversy began that continued for years. The “protectionists” wanted to give the birds better protection in the wild, and if this did not work, to let them gradually disappear, to die with dignity in their natural habitat. They maintained that some condors were sure to be accidentally killed during capture; that they were unlikely to breed in captivity; and that, even if they did, it would be impossible to reintroduce them to the wild.

I remember visiting the San Diego Zoo during that period and discussing the issue with some of the scientists, including my longtime friend Dr. Donald Lindburg. Part of me shrank from the idea of depriving the wild birds of their freedom, imprisoning those wondrous winged beings in enclosures, perhaps for the rest of their lives. But another part felt—along with Don and Noel Snyder—that it would be worth it to save such a magnificent species, so long as they could be released back into the wild. In the end, Noel and Don and the other interventionists prevailed.

In June 1980, five scientists, led by Noel, set out to monitor the progress of the single chicks in each of the only two known “nests” in the wild. (For condors, nests are simply ledges of rock, usually in caves.) Imagine the team’s dismay when, after they had checked on the first chick without problems, the second died of stress and heart failure during the process. This, naturally, led to a storm of protest from the protectionists—which Noel somehow weathered.

In 1982, a hide was built near a wild condor nest so that the behavior of the birds could be studied. The observers could hardly believe the extraordinarily dysfunctional behavior they witnessed. Every time the female returned to take her turn at incubating her egg, she was subject to violent aggression from her mate, who apparently did not want to relinquish care of the egg. The male repeatedly chased her from the nest cave, sometimes continuing to do so for days, while the egg meanwhile suffered unnaturally frequent and long periods of cooling. Finally, during one such squabble, the egg rolled out of the nest cave and smashed on the rocks below.

The observers thought that this meant a sad end to the pair’s reproductive activities for the year. But a month and a half later, they produced another egg, which was laid in a different cave. Although this egg was also lost when the pair resumed squabbling—this time to a raven—the study was important because it established that condors, like many other birds, will be stimulated to breed again and lay replacement eggs if they lose one to predation or some kind of accident. Noel and his team then began a major effort to establish a captive breeding population by taking first-laid eggs from all wild pairs for artificial incubation.

How fortunate that they did, for over the winter of 1984–1985, tragedy struck the wild population. Four of the five known breeding pairs were lost. Reasons for the birds’ disappearance were unclear, but there was mounting evidence that they were dying from lead poisoning. At this point, Noel and his team felt it imperative to capture the remaining wild birds. There were so few condors in the breeding program and they lacked the genetic variability to be self-sustaining—and there were but nine wild birds left. Only by establishing a viable captive population, Noel maintained, could the California condor be saved.

The National Audubon Society, however, strenuously opposed this plan, arguing that habitat could not be protected for the species unless some birds were left in the wild. In an attempt to prevent taking the last wild condors captive, the group sued the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). But after the female of the last breeding pair became a victim of lead poisoning and died, despite attempts by veterinarians to revive her, a federal court ruled that the USFWS did indeed have the right to capture the remaining wild birds. And so, between 1985 and 1987, the last wild California condors were taken into captivity, and the species became officially extinct in the wild.

By this time, two state-of-the-art breeding facilities had been established, one in the San Diego Wild Animal Park and the second in the Los Angeles Zoo, each with six enclosures. During five years, starting in 1982, sixteen eggs (of which fourteen hatched and survived) and four chicks were taken from the wild and shared between the two facilities. And there was one male, Topa-topa, who had been living in the Los Angeles Zoo since 1967. These captives were then joined by the last seven adults from the wild. Bill Toone was in charge of incubating the eggs, and thanks to the techniques he and his team developed, 80 percent of the eggs resulted in healthy young birds—compared with a 40 percent to 50 percent success rate in the wild.

In the early 1990s, Don invited me to visit the condor breeding center and flight cage at the San Diego facility. As with most such programs when reintroduction into the wild is an end goal, great care was taken to ensure that the captive-bred condors did not imprint upon their human keepers. Those caring for the chicks were equipped with glove puppets mimicking the head and neck of an adult condor, and no talking was allowed near the birds. In silence I peered through one-way glass and saw one of the original wild hatched females sitting, unaware of my presence, on a ledge of man-made rock. As I watched her suddenly take off and, with only a couple of flapping movements, glide on those majestic wings across her very large flight cage, I felt tears sting my eyes. Partly because of her lost freedom; partly because I knew that but for a handful of passionate, courageous, and determined people, this glorious winged being would almost certainly have died—shot or poisoned—like so many others before her.

More than two decades later, in April 2007 (on my birthday!), I visited the Los Angeles breeding program and met team members Mike Clark, Jennifer Fuller, Chandra David, Debbie Ciani, and Susie Kasielke. We gathered in a small room where video screens showed the twenty-four-hour recordings of behavior in the breeding enclosures. As we talked about the successes and problems of the program, we watched on a monitor (from a remote camera set up in a breeding pen) a wonderful courtship display by a young male. And there was a female there that was getting ready to lay her first egg. It was not due for several days, but already she was looking most uncomfortable, her tail raised and her head low. She pecked up and swallowed a few small fragments of bone, a behavior thought to provide extra calcium for building the egg’s shell.

An urgent problem facing the pioneers who embarked on captive rearing was to find the correct method of raising the young birds for ultimate release. Because the California condors were so perilously close to extinction, they could not afford to make many mistakes. So the team decided to carry out a trial release with Andean condors, since this species, with its fabulous eleven-foot wingspan, is not nearly so endangered. Thirteen youngsters would be raised and released temporarily in Southern California, allowing the team to test their methodology before any of the precious Californians were freed. The Andeans, all females, were raised as a peer group and all released at the same time. It was thought that they would provide one another with companionship and support one another. And indeed, it worked well. (The Andean condors were later recaptured and ultimately re-released in Colombia, where many are now breeding and rearing chicks of their own.)

Flushed with the success of the Andean program, the biologists confidently raised their young California condors in the same way. Alas, Mike told me, group rearing simply did not work for them and led to all manner of behavioral problems. It seems that California condors need discipline from an adult bird. And so a new method was devised. Each chick remains for the first six months in a solitary nest box, in view of an adult male condor, cared for and fed by a disguised human using a condor head puppet. Then, at the time when a wild fledgling would leave the nest, the youngster joins an adult mentor—a male of ten years or older. This mentor competes for food with the young bird but without being aggressive and is, said Mike, “good for its mental development.”

However, as the condors matured, additional behavioral problems arose. For one thing, proper male–female bonding was not happening until, through trial and error, scientists learned that putting a mature male and female, genetically suitable for each other, in an enclosure with young birds worked best. “Each adult bird then prefers the other’s company over that of any of the youngsters,” said Mike.

Once bonding is achieved, mating is no problem, and such pairs regularly produce eggs. And the raising of chicks by parents in captivity was also relatively trouble-free. “The sight of an egg,” said Mike, “seems to trigger an instant paternal response in the male, who becomes very protective of it.” The pair take turns incubating the egg for the fifty-seven days before it hatches. After this the male continues to be very protective, though the mother tends to compete with her chick for its father’s attention.

By 1991, eleven of twelve captive pairs had produced twenty-two eggs. Seventeen of these were fertile, and thirteen had hatched and matured. Things were going well. By 1992—less than ten years after the program began—the first two captive-bred condors, each with a radio tag, were released into 398,000 acres of protected wilderness, including thirty miles of protected streams, in Los Padres National Forest. In an attempt to protect these birds as much as possible from the risk of lead poisoning, food was (and still is) set out near the release site. Even though they can fly more than a hundred miles in a single flight, it was hoped that these California condors would, as had the test group of Andean condors, return to easily available food when hungry—which they mostly did.

In 2000, the first captive-bred birds nested in the wild—an event that is always awaited eagerly by the people who have worked so hard to return animals to a life of freedom. But it was at this time that some of the behavioral problems affecting the captive-raised birds became apparent. When biologists found the nest, they were amazed to see not one but two eggs! And they discovered that there were three birds to this one nest, one male and two females. They had, however, chosen a very appropriate cave, where the females had laid eggs several feet apart. The three took turns sitting at the nest site—but one bird could not sit on both at once, and so the biologists decided to intervene.

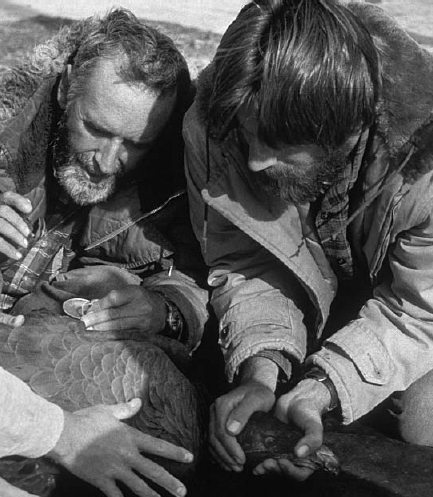

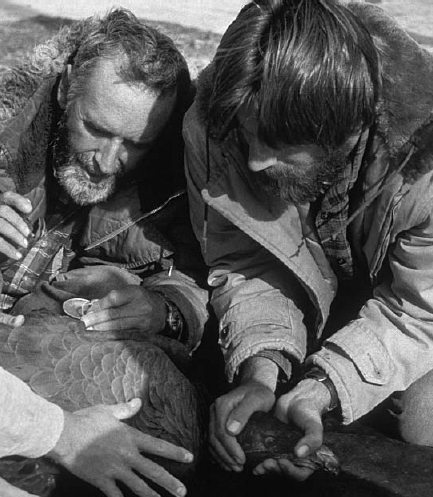

The first condor to be provided with a radio transmitter was IC1 (shown here with Noel Snyder, left, and Pete Bloom), who was trapped in the Tehachapi Mountains. Transmitters make it possible to track the progress of condors in the wild. (Helen Snyder, courtesy US Fish and Wildlife Service)

They found that one of the eggs was completely rotten. They then left a dummy egg and took the other to see if it was viable. It turned out to be in poor shape, but the skilled staff managed to hatch it at the zoo. Meanwhile, the unlikely trio was still caring for the dummy egg in the wild. Just before the egg should have hatched, it was replaced with a healthy, captive-laid egg. A chick duly hatched, but despite the presence of three potential caregivers, one of the females was left alone—first with the egg and then with the chick—for eleven days straight. And when the second female finally returned, instead of helping to nurture the three-day-old chick—she killed it. That was certainly not a very successful breeding season! Still, it was encouraging that the three would-be parents had nested in a suitable location and among them had at least hatched an egg.

The following year, chicks were hatched in three nests. But initial excitement turned to dismay when, at about four months old, all three youngsters died. When they were subsequently examined, it was found that the parents, in addition to providing them with normal food, had been feeding them trash—items such as bottle tops, small pieces of hard plastic and glass, and so on.

Unfortunately, this has become a tradition in this population—and they are not alone, as vultures in Africa have also been observed feeding trash to their young. Biologists believe that the parents are picking up these inappropriate objects as substitutes for the bone fragments thought to help in bone development.

Today the recovery team keeps close watch on the nests to record parental behavior and chick development, and they check the health of eggs and chicks at regular thirty-day intervals—with a mandate to intervene if necessary. And it was necessary with the only chick hatched in the 2006 breeding season. This is a fascinating story. For one thing, the parents had both been considered too young to produce an egg—the female was only six years old and the male, only five. They had not even acquired adult plumage, and finding them with a nest and egg was a huge surprise. Mike told me that they were all worried because of the youth and inexperience of the parents—would they be able to sustain interest in the egg during the long incubation period?

So the team played a trick. Members took away the egg of the inexperienced couple, which would not hatch for another month, and left in its place an egg from the captive breeding program that was on the verge of hatching. The young parents, hearing the vocalizations of the chick inside the new egg and the pecking at the inside of the shell, instantly became very attentive. The chick hatched successfully and was well cared for.

When its health was monitored after thirty days, all seemed to be going well, although some trash fragments had been brought to the cave floor. The team spread five pounds of bone fragments around, hoping this might mitigate the extraordinary passion for feeding trash, and left, hoping for the best. The sixty-day checkup also found the chick healthy. The parents had left more trash fragments lying around, but the metal detector—now standard veterinary equipment!—showed that the chick had not swallowed any. However, when they checked up after ninety days, they found a very sick, underweight, and undersize chick that had swallowed a great deal of trash. It was obvious he would die if this was not removed.

Mike picked up the chick and took it back to the Los Angeles Zoo—which does veterinary work on all the wild condors in California—for emergency surgery. Meanwhile, another member of the team stayed overnight to keep the parents out of the nest site—for had they found it empty, they would almost certainly have left. Inside that chick was an extraordinary array of trash, ranging from bottle caps to small pieces of metal and hard plastic, all tangled in cow hair. I saw the collection, and it was hard to believe it all came from one bird, let alone a chick. No wonder it was sick! The surgery went well, and twenty hours later the youngster was returned to its nest by helicopter and delivered on the end of a rope by a search-and-rescue specialist. During this operation the parents were right behind the humans, peering past them at the nest—and five minutes after the helicopter left, they were back with their beloved offspring.

Without his load of indigestible trash, the chick’s health improved. But just before the 120-day check, the field biologist on duty, observing the nest through a high-powered scope, noticed the chick playing with three pieces of glass, swallowing them and spitting them out. And sure enough, when team members went in to check him at the prescribed time, they could feel something hard in his crop. Fortunately, they were able to massage the objects gently out of the crop and into the throat, then remove them with forceps—they were the same three pieces of glass that he had been seen playing with. This preoccupation with trash is certainly one of the worst behavioral problems that the team must try to solve.

One suggestion to reduce behavioral problems was to release some of the original wild-caught birds from the 1980s to serve as role models. This was done, but while these birds do indeed represent a priceless behavioral resource, part of their behavior is wide-ranging foraging, which can make them especially susceptible to lead poisoning—and in fact, one of the original females did suffer serious lead poisoning after her return to the wild. Noel feels strongly that no more should be released until the lead-contamination problem has been solved.

From the very start, Noel told me, nearly all program personnel have agreed that this issue is critical. But for more than twenty years—since the first sick condors were diagnosed with lead poisoning—nothing was done to remove the source of the problem, largely because no good substitutes for lead bullets existed. By 2007, however, a variety of nontoxic ammunition had come on the market, and on October 13 that year Bill AB 821 prohibiting the use of lead bullets for hunting large game in the range of the California condor was signed by California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and subsequently passed by the legislature. This was the result of pressure on the lawmakers from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and many conservationists.

Some environmentalists felt that the bill was a cop-out—that so long as the bullets were made, it would be hard to enforce the law. But when I talked with Governor Schwarzenegger about this, he said that the range of the condors was so vast, there was not much of California left where lead bullets could be used. He thought manufacturers would not think it worthwhile to continue making them. In any event, passing this bill is a major step forward, and I, for one, congratulate the governor for supporting it.

Although the future of the released individuals is not assured, the investment, in time and the commitment and dedication of the men and women involved, has been a success—for without intervention, the California condor would most certainly have gone extinct. Instead, there are nearly 300 of these magnificent birds, and 146 of them are out in the wild, soaring the skies above Southern California, the Grand Canyon region of Arizona, Utah, and Baja California.

Those who watch the condors in the wild are moved. Mike Wallace, one of the field biologists who oversaw the release of captive-bred condors in the Baja, sent me a wonderful story about observing the mating rituals and unique personalities of these amazingly social birds (which you’ll find on our Web site janegoodallhopeforanimals.com). My friend Bill Woolam wrote to me about the wonder of seeing this giant bird when he was hiking in the Grand Canyon—watching the condor flying up and up with those huge and powerful wings, hearing the wings flapping and the air whistling through the feathers as the condor glides down—the music of flight. And Thane, too, recently wrote to me about the joy of seeing five of the fifty or so condors living near the Grand Canyon when he was rafting there in 2008.

The more people who have this kind of experience, and who realize how nearly this amazing bird vanished forever, the more they will care. And their number is growing—there are legions of people who are passionate about California condors and their future. Noel, though officially retired, still feels a great personal commitment. The condor, he told me, “comes to dominate your life whether you like it or not.”

I have a legal permit to carry a twenty-six-inch-long wing feather from a condor. During my lectures, as Thane mentioned in his foreword, I love to take this by the quill and pull it, very slowly, from its cardboard tube. It is one of my symbols of hope and never fails to produce an amazed gasp from the audience. And, I think, a sense of reverence.