Imagine finding a living species previously known only from fossils! A species from an ancient prehistoric world that has existed, beyond our knowledge, for millions of years. The coelacanth, an enormous shark-like fish, was discovered just before World War II. Because I was only four years old, it was not exciting to me at the time. It is very exciting to me now. An animal species that has survived, unchanged, for sixty-five million years! And no one knew about it—except, I suppose, fishermen who had occasionally caught one in their nets, and they would have had no idea that it was anything untoward. It was indeed known to science, but in the form of fossils, stored in various museums, of little interest to any save those paleontologists who happened to be interested in fish. For them, the discovery was as though a living dinosaur had been found!

When I worked with Louis and Mary Leakey at Olduvai in 1958, I would sometimes stand, holding the fossilized bone of some long-gone species, and imagine how it would have looked in life. Indeed, it sometimes led to near-mystical experiences. As when I found the tusk of an extinct giant pig and seemed suddenly to see it standing there, huge and fierce. Saw its coarse brown hair, the crest of black hair along its back, its bright fierce eyes. I seemed to smell the animal, hear it snort. And then it was gone and I was left looking down at a piece of prehistoric ivory, slowly returning to reality.

The coelacanth comes from a far more ancient era than that pig. It is as though one of the fish, from those prehistoric seas I had longed to visit as a child, has come swimming into the present. And I can so easily imagine the overwhelming feeling of excitement of the scientists who handled and studied that first coelacanth. Indeed, they must sometimes have imagined they were dreaming.

The Wollemi pine was also known only from the fossil record—from imprints of its leaves on ancient rock. And it, too, dates back sixty million years. When the first specimen was picked from a tall tree in a remote and unexplored canyon in Australia, the biologist who found it had no idea that he had made a major discovery, that he would have the extraordinary honor of having a “living fossil” named for him. Indeed, it took a long time and many hours of discussion and searching through herbarium specimens before its true identity was finally revealed. That was truly the botanical discovery of the last century, just as the coelacanth was one of the major discoveries in the animal kingdom. The future of the tree is assured—that of the fish is uncertain. The stories of both are fascinating.

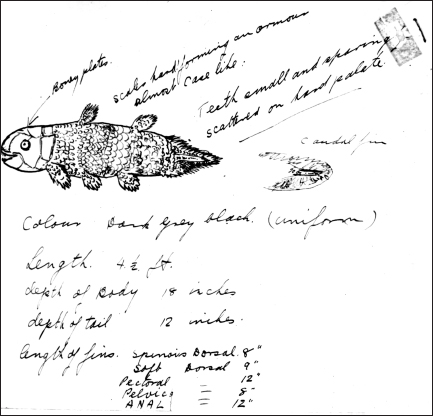

Toward the end of 1938, Marjory Courtenay-Latimer, a twenty-three-year-old museum curator in East London, South Africa, noticed a very strange-looking fish in the catch of the trawler Nerine. She often went to look at the sea life brought in by the fishermen, but she had never seen anything like this before. In an interview, she said it was “the most beautiful fish I have ever seen, five feet long and a pale mauve blue with iridescent silver markings.” She and the museum staff knew that it was unique and of great scientific value. She preserved as much of the fish as possible, drew it, and sent the now famous sketch to renowned ichthyologist Professor J. L. B. Smith.

I would love to have been there when, finally, Professor Smith and the remains of that fish got together. Already there was speculation as to the identity of the deep-sea creature—and early in 1939, Smith announced to a stunned world that it was a coelacanth, a fish previously known only from the fossil record. It had been considered extinct for some sixty-five million years.

For the next fourteen years, no more coelacanths were reported, but then, in 1952, one was found in the Comoros. Professor Smith—I imagine with much excitement—went to fetch it. This find was considered so important that the then prime minister, Dr. D. F. Malan, allowed him to use a Dakota of the South African Air Force to transport the fish back to East London! More scientists became interested, and more attempts were made to try to see these fish in their natural habitat. And then came the first amazing footage of coelacanths swimming in the ocean. It was shot from the manned submersibles Geo and Jago by Professor Hans Fricke and his team.

In 1938 Marjory Courtenay-Latimer, a twenty-three-year-old museum curator in East London, South Africa, saw a strange-looking fish in the catch of a local trawler. She drew the fish, and sent this now famous sketch to renowned ichthyologist Professor J. L. B. Smith, who identified it as a coelacanth, a sixty-five-million-year-old species. (South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity)

Coelacanths are large fish growing to about six feet in length; the heaviest recorded so far was 243 pounds. Professor Smith wrote a book about them, which he titled Old Fourlegs—a reference to the lobed fins that he and other scientists thought might be precursors to the arms and legs of land vertebrates.

Historical photo of Marjory Courtenay-Latimer with a mounted coelacanth. (South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity)

Recently I was in touch with Dr. Tony Ribbink in Grahamstown, South Africa. He is the CEO of the Sustainable Seas Trust, founded to study and protect endangered species in the ocean canyons and caves of Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, the Comoros, and South Africa. He got involved with coelacanth research and conservation in 2000 when scuba divers discovered a colony in the Saint Lucia Wetland Park off Sodwana Bay, South Africa. They were more than a hundred yards deep when they found and filmed coelacanths in canyons about two miles from the shore.

“The discovery of the coelacanths in a marine park and world heritage site,” he said, “was a wake-up call.” He likened it to finding elephants in a terrestrial park years and years after the park had been established. I asked if he had seen coelacanths in the wild. “Yes I have,” he told me, “at depths from 105 to over 200 meters. They are amazing—very quiescent, very tolerant of each other, slow moving and mystical.”

The South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity launched the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme, which works in Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, South Africa, and Tanzania. They have engaged hundreds of researchers, students, and public officials from nine countries and gradually gained new insights into the ecology, distribution, and behavior of these amazing survivors from ancient times. But still many of the fundamental questions, asked initially in the late 1930s by Marjory Courtenay-Latimer and Professor Smith regarding life history, breeding behavior, gestation period, where the young are born, whether parental care is practiced or whether the young hide until they are large enough to join adult groups, remain unanswered. No one has ever knowingly seen a young coelacanth in the wild.

“When our research began in 2002,” said Tony, “only one coelacanth was known from Mozambique, one from Kenya, four from Madagascar, some from Comoros, and we know that our South Africa population has at least twenty-six individuals.”

In 1979, a coelacanth was found off Sulawesi by an Indonesian fisherman. This turned out to be a different species, Latimeria menadoensis. Another of these, again off Sulawesi, was caught alive in 2007 and actually lived, in a quarantined pool, for seventeen hours.

Tragically, these living fossils—which have survived innumerable stresses over the millennia yet remained essentially unchanged—are now vulnerable to extinction. This is because while they are fairly unpalatable and are not targeted by fishermen, they are caught accidentally as a bycatch. Increasing demand for fish and a depletion of the inshore resources have seen fishermen move into deeper water to set gill nets, thus penetrating the habitats of the coelacanth around Africa and Madagascar. The first coelacanth bycatch recorded in Tanzania was in September 2003; since then, nearly fifty have been caught. All have died. This represents the greatest known rate of coelacanth destruction anywhere.

Fortunately the Tanzanian authorities, with the help of the Sustainable Seas Trust, are planning to develop, off the coast of Tanga, one of several marine protected areas. These refuges are not exclusively for coelacanths but are part of a plan to protect special offshore ecosystems while working out sustainable ways of harvesting them to benefit coastal human communities as well as the fish. But the coelacanth is of such importance that a major awareness campaign has been launched to let the people know about the extraordinary prehistoric fish in their waters.

“Coelacanths are rare, beautiful, and intriguing,” says Tony. “They have brought together people of many cultures and countries, and inspired a more harmonious relationship between us and the rest of the living world. To the countries of the Western Indian Ocean, they are an icon for conservation—the panda of the sea. And a symbol of hope.”

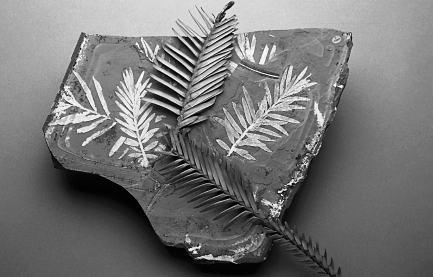

A fossilized branch alongside a recent clipping of the rediscovered Wollemi pine that belongs to the two-hundred-million-year-old Araucariaceae family. (© J. Plaza RBG Sydney)

On Saturday, September 10, 1994, David Noble, a New South Wales national parks and wildlife officer, was leading a small group in the Blue Mountains of Australia about a hundred miles northwest of Sydney, searching for new canyons. David has been exploring the canyons of these wild and beautiful mountains for the past twenty years.

On this September Saturday, David and his party came across a wild and gloomy canyon that he had never seen before. It was hundreds of yards deep, the rim fringed by steep cliffs. The party abseiled down into the abyss, past numerous small waterfalls of sparkling water. They swam through the icy waters, and then hiked through the trackless forest. During this adventure, David noticed a tall tree with unusual-looking leaves and bark. He picked some of the leaves and put them in his backpack, then forgot about them until he got home and retrieved a slightly crushed specimen. He first tried to identify it himself but could not find anything to match. He had absolutely no idea that he had just made a discovery that would astound botanists and enthrall people all over the world.

When he showed the battered leaves to botanist Wyn Jones, Wyn asked if they had been taken from a fern or a shrub. “Neither,” David replied. “They came from a huge, very tall tree.” The botanist was puzzled. David helped in the search that followed, looking through books and on the Internet. And gradually the excitement grew. As the weeks went by, and the leaves could not be identified by any of the experts, enthusiasm grew even more.

Eventually, after many botanists had pored over David’s leaves, it became clear that the tree was a survivor from millions of years ago—the leaves matched spectacular rock imprints of prehistoric leaves that belonged to the two-hundred-million-year-old Araucariaceae family.

Clearly it was necessary to find out a good deal more about this extraordinary tree, and David led a small team of experts back to the place where the momentous discovery had been made. As a result of that expedition, and exhaustive research into the literature and examination of museum samples, the tree, a new genus, was named, in honor of the finder, Wollemia nobilis, the Wollemi pine. It struck me, as I was talking to David, that for the sake of the majestic tree it was lucky that David had an appropriately majestic name. After all, it could have been found by a Mr. Bottomley!

It is indeed a noble tree, a majestic conifer that grows to a height of up to 130 feet in the wild, with a trunk diameter of more than 3 feet. It has unusual pendulous foliage, with apple-green new tips in spring and early summer, in vivid contrast with the older dark green foliage.

Continuing research showed that the pollen of this new tree matched that found in deposits, across the planet, dating from the Cretaceous period somewhere between 65 and 150 million years ago when Australia was still attached to the southern super-continent of Gondwana. One professor of botany, Carrick Chambers, the director of the Botanic Gardens Trust–Sydney, exclaimed in wonder: “This is the equivalent of finding a small dinosaur alive on earth.”