Stephen Pleasonton, the fifth auditor and superintendent of lighthouses.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Stephen Pleasonton, the fifth auditor and superintendent of lighthouses.

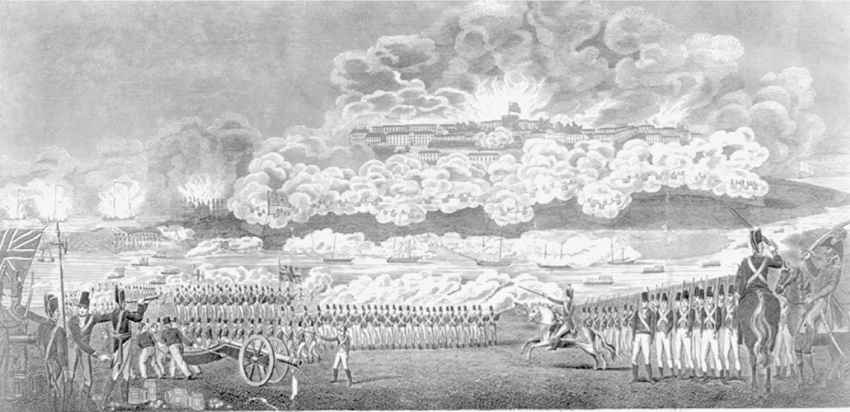

STEPHEN PLEASONTON OWED HIS JOB AS AMERICA’S FIFTH auditor in large part to being in the right place at the right time during the waning days of the War of 1812. On August 24, 1814, as British troops were bearing down on Washington, Secretary of State James Monroe, who had been monitoring the British advance, sent a rider back to the State Department with urgent instructions. Believing that a British takeover of the capital was a virtual certainty, Monroe ordered his staff to do whatever it could to keep critical state papers from falling into enemy hands. Pleasonton, a senior State Department clerk at the time, immediately purchased bolts of linen, and with the assistance of coworkers fashioned the fabric into carrying bags, in which they carefully placed many of the jewels of American history, including precious documents such as the Declaration of Independence, the secret journals of Congress, and George Washington’s correspondence. Witnessing this frantic activity, Secretary of War John Armstrong told Pleasonton there was no need for such alarm since he thought a British attack unlikely. Pleasonton replied that Monroe held a different view, and in any case it was better to be prudent and save the documents, rather than risk them being purloined or even destroyed by an enemy force.

Pleasonton loaded the bags into carts and took them across the Potomac River to Virginia, hiding them in a gristmill not far from Washington. Fearing that this was still too close to the threatened capital, Pleasonton took the documents to Leesburg, thirty-five miles away, and locked them in an empty house. Exhausted by this ordeal, Pleasonton retired to a local hotel, and the next morning learned that the capitol had been engulfed in flames the previous night. Fortunately for the nation, the documents Pleasonton secreted away, much like the paintings Dolley Madison had ordered removed from the White House, survived the war.

A few days after James Monroe was inaugurated president in early March 1817, he rewarded Pleasonton, his faithful clerk, by appointing him fifth auditor. This position as yet had nothing to do with lighthouses. Pleasonton’s responsibilities included managing all the financial affairs of the State Department, the Post Office, and those relating to Indian trade. He was, in effect, a government accountant, tracking expenses, paying bills, and balancing ledgers. It wasn’t until 1820 that the secretary of the Treasury expanded Pleasonton’s portfolio by giving him oversight of lighthouses, a position that earned him the unofficial title “superintendent of lighthouses.”

British engraving of the capture of Washington on August 24, 1814, showing the capitol ablaze, circa 1815.

Forty-four years old at the time, Pleasonton was a hardworking, methodical government bureaucrat. The only known portrait of him is not very flattering. Jaws clenched, his lips turned sharply downward at the corners, he appears to be a very serious if not mirthless man. But one image cannot truly capture someone’s personality, and according to at least one of his friends, Pleasonton “was a very kind hearted gentleman with much dry humor,” who exhibited considerable “bonhomie.”

Pleasonton had no particular skills that would recommend him for his new task, which required him not only to manage the nation’s lighthouses, but also other navigational aids, including unlighted beacons, buoys, and, in later years, lightships, which were ships that shone lights from their masts and were moored in locations where it was impracticable to locate lighthouses. Pleasonton knew virtually nothing about lighthouses; neither did he have any experience with maritime issues or any engineering or scientific background. His strengths were those an auditor would be expected to have. He focused on the money, and his primary professional goal was to protect the government purse and cut costs wherever possible.

In 1820 there were 55 lighthouses nationwide, a number that spiraled to 325 by the time Pleasonton’s extraordinary thirty-two-year tenure ended in 1852. Pleasonton’s method of lighthouse management remained relatively unchanged throughout this period. After Congress decided where lighthouses were needed, usually based on petitions from state and local officials, and appropriated requisite funds, Pleasonton’s office issued the design plans for the buildings and then sent them to the customs collectors where the lighthouses were to be located. The collectors put the plans out for bid, and then Pleasonton, per government rules, chose the lowest bidder for the job. The collectors typically oversaw the selection and purchase of the building site, and in making the selection usually relied on the advice of local mariners and officials. When the contractor finished the project, a mechanic was required to certify that the work was done properly before final payments were made and the lighthouse accepted by the government. While the secretary of the Treasury officially appointed keepers, customs collectors were responsible for nominating, hiring, paying, and firing them. Collectors also were supposed to visit the lighthouses annually, report back to Pleasonton on their condition, and arrange for any necessary repairs. Contractors were hired to supply oil to the lighthouses and install the lighting apparatus, which invariably were Lewis’s patent lamps.

In line with his cost-cutting philosophy, Pleasonton rigidly controlled lighthouse finances, with every significant expenditure having to gain his approval. He was especially proud of consistently spending less than Congress appropriated, and returning a surplus to the federal Treasury. At one point he claimed that his sterling record of coming in under budget was “unexampled, so for as I know, in the annals of government.”

While he focused obsessively on costs, he was far less engaged in the technical aspects of lighthouse operations, which did not fall naturally within the realm of his expertise. As a result he relied heavily on advice from both collectors and contractors in assessing the effectiveness of the lighthouses.

Pleasonton relied most of all on Winslow Lewis, viewing him as the lighthouse expert, and often turning to him for guidance on lighthouse design and operations. After all, when Pleasonton arrived on the scene, Lewis was the accepted expert. The government had purchased his patent, making his lamps the nation’s official standard of best lighting practice, and Lewis was intimately familiar with every lighthouse in the country, having visited and illuminated all of them. Furthermore, Lewis knew a great deal about broader maritime issues, and was well connected within the shipping community, having just completed a two-year term as president of the Boston Marine Society.

The two of them, Pleasonton and Lewis, developed a strong professional and personal relationship, built in part on their shared parsimoniousness and eagerness to keep costs to a minimum. Lewis not only continued to be the main supplier of oil until the late 1820s, when the contract went to New Bedford whaling merchants, but he also became deeply involved in lighthouse construction, ultimately building, according to his own estimate, eighty lighthouses, an impressive record achieved as a result of his ability so frequently to submit the lowest bid. Lewis’s influence on lighthouse construction went far beyond just building them, for he provided Pleasonton with designs for lighthouses, which Pleasonton often used as the basis for the building plans issued by his office.

With the same ruthless cost-cutting approach he used to win building contracts, Lewis also won the vast majority of the contracts to illuminate the lighthouses, providing them, of course, with his patented lamps. Commenting on Lewis’s penchant for underbidding the competition, Pleasonton noted that Lewis “would work for nothing … sooner than give up a branch of business in which he has been engaged for more than thirty years.” Although there have been murmurs over time that the relationship between Pleasonton and Lewis might not have been entirely aboveboard, as the lighthouse historian Francis Ross Holland, Jr., has pointed out, there isn’t any “ ‘hard’ evidence that there were any shady dealings between” the two, and given Pleasonton’s pristine reputation for rectitude it seems unlikely that the national overseer of lighthouses would have accepted kickbacks.

As many as ten clerks worked for Pleasonton, but not all of them focused on lighthouse issues. Their assistance was essential, especially since Pleasonton’s responsibilities as fifth auditor later expanded to include the Patent Office and settling a wide range of accounts concerning foreign commerce. This added workload stretched Pleasonton thin, further reducing the amount of time he could devote to lighthouse affairs.

The management scheme that Pleasonton devised served his needs, but as would become painfully clear in the coming years, it didn’t serve the best interests of the nation or the mariners who plied its shores.

_____

UP THROUGH THE MID-1830S, roughly 150 new lighthouses were built, an expansion that reflected the dizzying industrial growth of the adolescent nation. Most of these beacons were located along the coasts of the New England and the mid-Atlantic states, but lighthouses were also added in places farther afield. The opening up of what would become America’s heartland, and the increasing flow of goods such as grain and timber over the Great Lakes, made lighthouses a necessity for safer travel. What early traders and shippers quickly apprehended was that these magnificent inland seas, covering roughly 95,000 square miles, were every bit as dangerous to shipping as the oceans of the world, capable of generating enormous waves and punishing conditions that could, and often did, sink ships. Even before Pleasonton’s responsibilities expanded, the first lighthouses on the Great Lakes were built in 1818 on Lake Erie, at Buffalo and Presque Isle (now part of Erie, Pennsylvania), and lit the following year. Others followed, including the Rochester Harbor Lighthouse on Lake Ontario (1822), the Cleveland Lighthouse on Lake Erie (1829), the Thunder Bay Island Lighthouse on Lake Huron (1832), and the St. Joseph Lighthouse on Lake Michigan (1832), forming a ribbon of sorts that illuminated the Great Lakes.

When the Erie Canal opened in 1825, connecting the Hudson River at Albany to Lake Erie at Buffalo, it not only increased the amount of shipping on the Great Lakes, as traffic between New York City and the heartland soared, but it also created a need for lighthouses along the Hudson to help ships navigate to and from the canal. The first one, built in 1826 at Stony Point, just below West Point, warned ships away from the rocks of Stony Point Peninsula.

Lighthouse expansion was hardly an exclusively Yankee affair, for this period also saw the addition of lighthouses along the Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana coasts. Arguably the most important extension of the lighthouse establishment was on the Florida coast, in particular along the Florida Keys. A 185-mile-long coral archipelago that curves in a graceful arc from Virginia Key off Miami to the Dry Tortugas, the Florida Keys had long been one of the most perilous places for ships. Beginning in the 1500s, Spanish vessels transporting the riches of the so-called New World back to the Old, had skirted the Keys on their way from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic, trying to avoid crashing into the jagged reefs and sandbars lying just offshore. After the United States acquired the Louisiana Territory in 1803, American mariners were forced to run the same gauntlet as the watery passage by the Keys became a busy commercial highway, connecting the burgeoning port of New Orleans with the rest of the United States as well as Europe. An untold number of ships failed to negotiate the Keys, and the resulting wrecks became the foundation for an extremely lucrative industry, in which individuals called wreckers salvaged the disabled vessels for profit.

In 1819, under the terms of the Adams-Onís Treaty, Spain dramatically ceded Florida to the United States, and two years later the treaty was ratified. Soon after, the idea of lighting the Keys in an effort to reduce the number of wrecks gained currency. In early 1822 the navy ordered Lt. Matthew C. Perry, who would later gain fame for “opening up” Japan in the 1850s, to officially take possession of Key West and explore its potential as a naval base. While performing this duty, Perry wrote a letter to Smith Thompson, the secretary of the navy, encouraging him to tell the Secretary of the Treasury that there was a “great want of lighthouses on the Florida Keys,” adding that building some there would render Florida’s shores “more safe and convenient.” At the same time merchants, shipowners and captains, and insurance companies were also busy lobbying in favor of lighting the Keys. Congress responded on May 7, 1822, issuing the first of many appropriations, and over the next six years lighthouses were built at Cape Florida (1825), the Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas (1826), Key West (1826), and Sand Key (1827).

Other than the Indians who were forcibly and tragically expelled from their land, perhaps the only people who weren’t happy about the lighthouses in the Florida Keys were the wreckers. The business of salvaging ships was not peculiar to Florida. Since time immemorial, wreckers have worked shores the world over, and there were wreckers all along America’s eastern seaboard seeking to profit from other people’s misfortune. Wreckers were often called, in high American slang, “mooncussers” because they supposedly prayed for dark and cloudy nights, and were thought to curse the brightly shining moon since it helped mariners find their way. By the same logic, wreckers were also assumed to be, and were often accused of being, against the building of lighthouses. There doesn’t appear to be any evidence of this in the Keys, but farther to the north, in New England in particular, there are many such anecdotal stories. In the early 1850s, while touring Cape Cod, Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, was told by the keeper of the Nauset Lighthouse in Eastham that local wreckers, eager to keep their business brisk, strongly opposed the building of the lighthouse. To overcome such resistance, local proponents of the lighthouse had to venture to Boston to obtain the recommendation of the city’s marine society.

Wreckers were also accused of a far worse activity—using false lights on dark nights to lure ships into danger in order to generate more business. In some accounts wreckers would tie lights to horses or cows and walk them along the beach, simulating a ship’s light, potentially drawing ships unfamiliar with the area to follow the light and come to grief on a reef or shoal. At other times it was claimed that lights placed atop poles were intended to confuse mariners into thinking they were the beam from a lighthouse, with similar baleful results. Such tales were often bandied about all along America’s Eastern Seaboard, from the Keys on up, but there is great debate over whether wreckers ever acted so abominably. And, understandably, given the nature of such nefarious activity, and the desire of perpetrators to hide their deeds, there is no known reliable evidence that false lights were actually used in the United States. Nevertheless there must be some truth to the tales, because in 1825 Congress passed a law that made it a crime to “hold out or show a false light, or lights” with the intent of causing a wreck, and anyone found guilty of this felony could be fined up to five thousand dollars and imprisoned up to ten years.

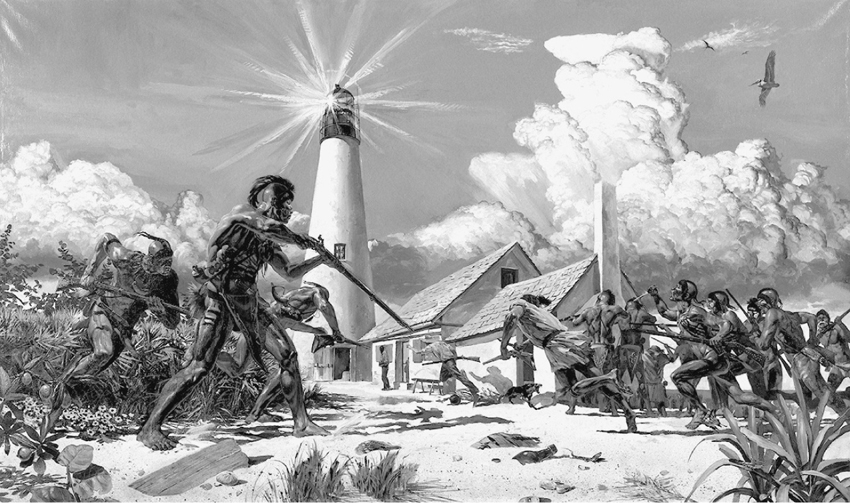

CAPE FLORIDA LIGHTHOUSE on Key Biscayne was not only the first lighthouse in the Keys, it was also the site of one of the most dramatic stories in the history of America’s lighthouses, which took place on July 23, 1836. Florida at the time was contested land. The Second Seminole War had begun in 1835, with the Indians fighting American efforts to relocate the tribe beyond the Mississippi. In early January 1836 a band of Seminoles took control of the lighthouse, which had recently been abandoned due to the outbreak of hostilities. Given the lighthouse’s importance to shipping, Floridian merchant William Cooley agreed to lead a group of men to retake it.

Cooley and his armed retinue took up residence near the lighthouse at the end of January, and the Indians soon departed. A little while later the lighthouse keeper, John Dubose, returned to take over his duties, and until the early summer things were quiet, but there remained a residual fear that the Indians might come back. In July, Dubose went to Key West for supplies, leaving the lighthouse in the care of the assistant keeper, John W. B. Thompson, and a black man named Aaron Carter, who likely was Thompson’s slave.

At about four in the afternoon on July 23, as the sun in the bright blue sky was arcing toward the horizon, bringing to a close another scorching Florida day, Thompson was heading to the keeper’s house when out of the corner of his eye he spied a large group of Indians—as many as fifty—about twenty yards away. Sprinting for the lighthouse, he yelled for Carter to follow. The Indians discharged their rifles, and a few of the balls ripped through Thompson’s clothes and hat, while most of the rest blew small holes in the lighthouse’s door. As soon as Thompson and Carter were within the tower, Thompson locked the door, only moments before the Indians reached it.

Thompson had prepared for trouble, placing three loaded muskets in the lighthouse. He grabbed the guns and ran up the stairs to the second window, at the same time telling Carter to watch the door and let him know if the Indians attempted to break through. Thompson shot his guns in quick succession at the Indians gathered around the keeper’s house, and then he reloaded, ran to another window, and fired again. Finally Thompson ascended to the lantern room, firing, he said, whenever he “could get an Indian for a mark.” While Thompson was shooting, the Indians smashed the windows of the keeper’s house, and returned fire.

Thompson kept the Indians away from the lighthouse until dark. Then, however, his pursuers fired a furious volley and rushed forward, setting the lighthouse door and an adjacent boarded window ablaze. The flames breached the tower and rapidly raced up the wooden stairs. When they reached the landing where Thompson kept his bedding and clothes, the inferno exploded, fed by the 225 gallons of whale oil spewing from the tin storage tanks that had been pierced by the Indians’ bullets. Thompson grabbed a keg of gunpowder, his muskets, and ammunition, and raced to the lantern room. Then he went below to cut away the stairs. While Thompson was furiously sawing, Carter climbed from the bottom of the tower to join him. The scorching flames and acrid smoke drove Thompson back before he could saw all the way through the wood, whereupon he and Carter rushed to the lantern room.

Thompson covered the lantern room’s entryway, but the flames finally burst through, forcing him and Carter to retreat to the two-foot-wide iron platform outside. There they lay flat on their backs, the fire roaring on one side and agitated attackers down below on the other, firing up at them. With the “lamps and glasses bursting and flying in all directions,” his clothes on fire and his “flesh roasting,” Thompson attempted to put an end to his “horrible suffering” by throwing the keg of gunpowder into the fire, hoping to blow the tower to smithereens.

Attack on Cape Florida Lighthouse, 1836, as imagined by artist Ken Hughs in 1975.

The tower shook violently, and although it failed to fall, the stairs and the upper landings collapsed. This temporarily tamped down the fire, but then it rebounded as intensely as before. Carter, his body riddled by seven balls, was already dead. Thompson, too, had been shot, with three balls in each foot. Believing that he had no chance of surviving, he went to the outside of the iron railing, and after commending his “soul to God” was about to launch himself into the air, when something he could not describe caused him to stop and lie down again. He was lucky he had the chance, because while he was exposed at the railing, bullets from the Indians whizzed around him like “hail-stones.”

That night the Indians plundered and torched the keeper’s house. At about ten the next morning, one group of Indians loaded Thompson’s sloop with their booty and left, while the rest went to the other end of the island. “I was now almost as bad off as before,” Thompson later recalled, “a burning fever on me, my feet shot to pieces, no clothes to cover me, nothing to eat or drink, a hot sun overhead, a dead man by my side, no friend near or any to expect, and placed between seventy and eighty feet from the earth, and no chance of getting down, my situation was truly horrible.”

In the afternoon Thompson spied two ships in the distance. Marshaling his fast-waning strength, he used some of Carter’s bloody clothes to signal them, and soon the United States schooner Motto, accompanied by the sloop-of-war Concord, arrived. Having heard the explosion the night before, the men on board were coming to investigate, and on the way they recovered Thompson’s sloop, which had been stripped by the Indians.

A group of marines strode ashore, and quickly discovered that getting Thompson down was not going to be easy. To no avail, they tried using a makeshift kite to fly a line to the top of the tower. With night imminently approaching, the marines went back to their ship, promising Thompson they would return in the morning. When they did, they attached twine to a ramrod, shooting it from a musket to the top of the tower. Thompson grabbed the twine and fastened it to an iron stanchion. He then used the twine to pull up a two-inch-thick rope, which he also tied to the stanchion. Two marines then climbed up the rope and jerry-rigged a sling to bring Thompson back to earth. After a short stay in Key West, during which all but one of the balls in his feet were extracted, Thompson retired to Charleston. “Although a cripple,” he later wrote, “I can eat my allowance, and walk about without the use of a cane.” As for the Cape Florida Lighthouse, it was not repaired until 1846, due to delays caused by the continuing hostilities between the U.S. military and the Seminoles.

AT ABOUT THE TIME that the Cape Florida Lighthouse was being attacked, America boasted a string of more than two hundred lighthouses. Pleasonton, though a skinflint in so many ways, was very pleased with that growth. He was especially proud of the quality of the light that Lewis’s lamps produced. Many of America’s mariners, however, were less enthused. For years they had been complaining that the lighthouses in Great Britain and France were far superior to the ones in America—and they were right.