“Miss Ida Lewis, the Heroine of Newport,” on the cover of the July 31, 1869, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Miss Ida Lewis, the Heroine of Newport,” on the cover of the July 31, 1869, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

ALTHOUGH THE MAIN JOB OF LIGHTHOUSE KEEPERS WAS TO tend to the lighthouse, they were also supposed to render assistance to people involved in wrecks, or otherwise in distress on the water. In doing so, keepers, much like firemen, saved thousands of people, often at great risk to their own lives, and perhaps it is this selfless quality that has cast an almost romantic glow on the American lighthouse keeper, a loving image frozen nostalgically in time. While many keepers can be counted among those who engaged in rescues that were both thrilling and memorable, at the top of such a historical list must stand Ida Lewis and Marcus A. Hanna. Their stories illustrate how keepers, by performing their job with exemplary dedication and courage, could become heroes.

Born on February 25, 1842, Idawalley Zoradia Lewis was the child of Capt. Hosea Lewis and Idawalley Zoradia Willey. To avoid confusion between the two namesakes, the daughter was referred to simply as Ida, while the mother was called Zoradia. Hosea worked as a coast pilot and on a revenue cutter for many years before being appointed keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse, in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1853. The lighthouse was a crude, short stone tower with a small lantern room on top. It stood about two hundred yards from the shore on a jumble of limestone ledges in Newport Harbor, known locally as Lime Rock. The lighthouse had no keeper’s quarters, so Hosea and his family lived in town, and he commuted to work by boat.

Twice daily Hosea dutifully rowed to the lighthouse to tend the light, with Ida frequently at his side. She would often take up the oars, and with that practice she grew into a skilled rower who learned the many moods of the sea and could handle a skiff in all types of weather. According to Ida Lewis’s biographer Lenore Skomal, Hosea would regale his daughter with stories of his seafaring past, and how he had risked his own life to save others’. Hosea also taught her how to rescue someone from the water, making sure to pull the drowning person over the stern rather than the side of the boat, to keep them from tipping the boat over. “It was her father,” Skomal writes, “[who] instilled in Ida the seed of heroism.”

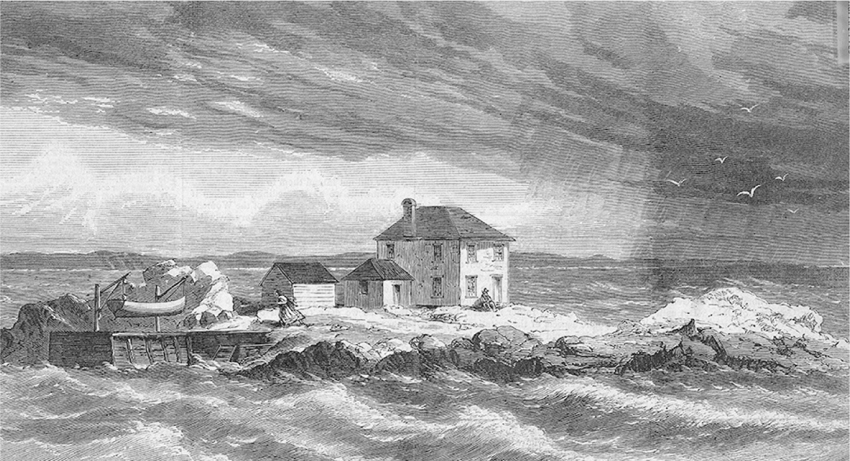

After more than two years of making these taxing treks to the lighthouse every day in all types of weather, Hosea’s health began to suffer. He pleaded with his superiors to build a keeper’s house on Lime Rock, arguing that it made much more sense for him to live next to the light so that he could better perform his duties. The board agreed, and by 1857 it had constructed a two-story granite-and-brick house, which had built into its northwest corner a square brick column with a small lantern room on top. Hosea could now tend to the lighthouse’s sixth-order Fresnel lens by simply accessing the lantern room via an alcove on the house’s second floor.

Engraving of the Lime Rock Lighthouse, off Newport, Rhode Island, as depicted in the July 31, 1869, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

The Lewis family moved in at the end of June, but calamity struck in October when Hosea suffered a crippling stroke that left him partially paralyzed and unable to perform his keeper’s duties. As a result, Ida, now fifteen, and Zoradia took on the responsibility of running the lighthouse, with Ida shouldering most of the load. In addition to her lighthouse duties, she also ferried her two younger siblings to and from school in Newport, and did supply runs to and from town, all the while strengthening her body and improving her boat-handling skills.

One year later, in September 1858, those skills were put to the test. Early that day four boys who attended a private school in Newport decided to take a catboat—a small, shallow-draft, wide-beamed sailing vessel with the mast near the bow—across the harbor for an island picnic. After eating, they sailed about beyond the harbor’s mouth, and then headed back. With the weather getting rougher, they lowered the sail, preferring to let tide carry them in. As they neared Lime Rock, Lewis could see them horsing around and hear them laughing. One of the party shimmied up the mast and began rocking back and forth, perhaps to amuse or scare his friends. This prank quickly backfired, as the boat capsized, pitching all four schoolboys into the water.

True to her training, Lewis reacted instantly, hopping into her skiff and quickly rowing to the boys. By the time she arrived, they were on the verge of drowning. The hull of the boat had sunk so low that it offered no purchase, forcing the boys to tread water. But being immersed had numbed their limbs, and the weight of their wet clothes was dragging them down. While the boys flailed about, struggling to keep their heads above water, Lewis, much as her father had instructed her, kept cool. Remembering Hosea’s teaching, she pulled the boys in one by one, over the stern, and then rowed them back to the lighthouse, where Zoradia handed out warm blankets and hot drinks. One of the boys was “so far gone,” teetering on the edge of consciousness, that he had to be revived with stimulants, possibly alcohol but most likely smelling salts. They all slowly came around, expressed their gratitude to Lewis, and went on their way.

Over the next decade Lewis continued to act as the keeper and lifeguard of Lime Rock, performing three more daring rescues in the harbor, including one that involved a sheep. On a particularly cold morning in January 1867, while a nor’easter was lashing Newport, three Irishmen who worked for a prominent local banker were herding one of his prize sheep down Main Street when it bolted toward the harbor. With the men in pursuit, the sheep jumped into the water and was soon swept farther offshore. The men ran along the harbor’s edge for a short distance before reaching Jones Bridge Wharf, where they spied an empty skiff. Despite the treacherous conditions in the harbor and their lack of boating skills, the men crowded into the skiff and set off after the wayward sheep, fearing that if they failed to save it they would soon be unemployed.

As related in a biography locally published two years later, lashing winter waves swamped the boat, which was rapidly drifting seaward, and when it capsized, the men found themselves in need of rescue. Ida had been sewing near a window when she heard the men’s piercing screams, and upon looking out she saw their predicament. She ran to her boat and expertly negotiated the rough seas to reach the skiff. As she got closer she could hear the men’s heavy Irish brogue as they prayed to God for deliverance. Upon seeing Lewis, one of the men reportedly exclaimed, “Oh Holy Vargin, and be jabbers, have you come to save me?” “(Such stereotypical language was fairly typical of the mid-nineteenth century, when the concept of political correctness lay more than one hundred years in the future.) After pulling the men on board, Lewis deposited them on Jones Bridge Wharf. Not done yet, seeing the sheep floating farther out to sea, she raced after it, tied a lasso around its neck, and rowed back to shore with the sheep in tow behind. The overjoyed Irishmen thanked Lewis, and left with their lives, their prize, and their jobs.

By early 1869 Lewis had saved nine people and one runaway ovine from the waters around Lime Rock, yet few beyond her family and those she had saved even knew that the rescues had taken place. Although a couple of them generated cursory mentions in the local newspapers, Lewis’s heroics remained largely unknown to the general public. Her next rescue that would change all that.

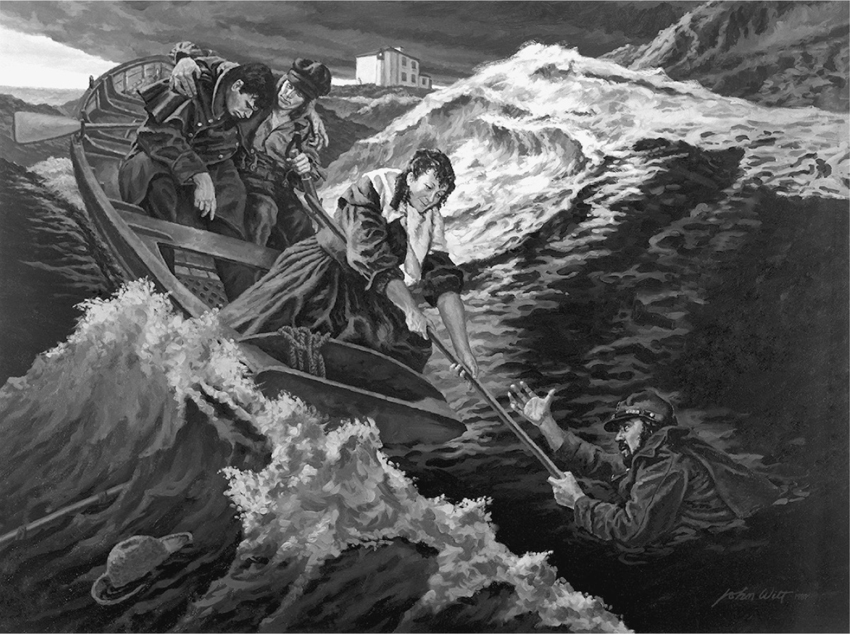

EARLY ONE EVENING IN March 1869, on her way to tend to the light, Zoradia Lewis looked out the window and screamed, “Ida, oh my God, Ida run quick, a boat capsized and men drowning, run quick, Ida!” About halfway between the lighthouse and Goat Island, Sgt. James Adams and Pvt. John McLoughlin, soldiers from Fort Adams, which sat on a peninsula to the west of Lime Rock, were desperately clinging to the hull of a boat. Earlier in the day, they had engaged the services of a fourteen-year-old boy, who boasted that despite the stormy conditions, he could safely ferry them from town to the fort for a small fee. The boy’s confidence, however, proved greater than his abilities, and when the boat capsized, he paid for his foolishness with his life. He had neither the strength to hold on to the boat’s hull nor the ability to tread water, and he soon sank beneath the waves, his body never to be found.

According to Mrs. Lewis it was “blowing a living gale and raining torrents” when she saw the men in distress, but that didn’t deter her daughter. Still battling a lingering cold, and without taking the time to put on shoes or a coat, Ida ran out of the house in her stockinged feet, with only a towel tied loosely around her neck for extra protection. Asking her younger brother, Hosea, to accompany her to help haul the men in, she was soon rowing to the rescue with him by her side.

Coast Guard commissioned painting of Ida Lewis rescuing soldiers James Adams and John McLoughlin, by John Witt, 1989.

Powering through the whitecapped waves that slammed into the skiff and threatened to swamp it, Lewis and her brother finally reached the stricken soldiers, and with great difficulty dragged them onto the boat. Weary from the strain, and now hauling more than twice as much weight, she leaned into the oars and returned to Lime Rock. By the time the skiff pulled in, Adams, drenched and shivering uncontrollably, was “barely able to totter up to the house,” while McLoughlin, who had passed out, had to be carried in.

Her feet nearly frostbitten, her aching muscles protesting her efforts, Ida warmed herself by the fire as her family cared for the soldiers, who slowly recovered. According to Ida’s older brother, Rudolph, Adams said, “When I saw the boat approaching and a woman rowing, I thought, she’s only a woman and she will never reach us. But soon I changed my mind.” The soldiers stayed overnight, and the next morning Ida, still exhausted from her earlier exertions, rowed them back to the fort.

UNLIKE HER PAST RESCUES, this one didn’t remain hidden from view. Exactly how word of the rescue spread is not clear, but soon papers in Newport and Providence ran stories detailing the event, and when one of those stories landed on the desk of an editor with the New-York Tribune, he immediately sent a reporter to Lime Rock to interview the young “good Samaritan.” The article that resulted ran on April 12, 1869, and detailed not only her most recent rescue but also the four that preceded it. The article dwelled on Lewis’s bravery and portrayed her as a hero, labeling her the “Guardian Angel of Newport Harbor” and the “Grace Darling of America.”

This last comparison was high praise indeed. Grace Horsley Darling had been hailed the world over for her part in a dramatic rescue off the Northumberland coast of England in 1838. Twenty-two years old at the time, the daughter of the keeper of Longstone Lighthouse, in the early morning of September 7 she was looking toward the ocean and the storm that was blowing when she saw a ship wrecked on Big Harcar Rock, an island about a mile from the lighthouse. It was the steamer Forfarshire, which had been bound for Dundee, Scotland. Grace alerted her father, William, who grabbed his telescope to look for survivors. They saw none at first, but a while later, as the sky lightened, they noticed movement on the rock. As the story is most often told, Grace urged her father to go with her to attempt a rescue, but he resisted at first, fearing that the seas were too rough, before finally agreeing to join her. Whether or not William was in on the decision from the start, the record is clear that both he and Grace soon shoved off in the lighthouse’s twenty-foot rowboat and headed for the rock. When they arrived they were able to take aboard only five of the nine survivors. After returning to the lighthouse, and dropping off his daughter and three of the survivors, William and two of the rescued men returned to the rock to collect the other four.

Engraving of Ida Lewis (center), and her mother and father, inside the keeper’s quarters at Lime Rock Lighthouse, as depicted in the July 31, 1869, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

News of the rescue soon filtered out, and Grace’s role in it catapulted her into the maws of the tabloid press that had recently come of age in early Victorian England. No longer was she just the keeper’s daughter, she had become a national hero, lionized for her bravery. She received an admiring letter from Queen Victoria, who was three years younger and only one year into her nearly sixty-four-year reign, the second longest of any British monarch. Darling was also awarded a gold medal by the Humane Society, entertained by nobility, and given a £750 purse, which was collected through a public subscription. Poems were written about her, portraits were painted of the winsome brunette, marriage proposals flooded in, and many people even requested locks of her hair as a memento of her daring deed. Just four years after the rescue, in 1842, the fearless Darling—who never sought and didn’t enjoy her sudden celebrity—died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-six.

As it turns out, Ida Lewis, who was twenty-seven, was about to experience a celebrity quite similar to Grace Darling’s. The glowing article in the Tribune set off a media feeding frenzy, and was soon followed by others in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, which were equally effusive about Lewis’s actions, with the Harper’s piece claiming that one of her earlier rescues of a soldier who was in danger of drowning “was a most daring feat, and required courage and perseverance such as few of the male sex even are possessed of.” These articles also included engravings depicting the heroine of Lime Rock. Many of the readers no doubt were surprised by the images, which showed a woman of average height and slender build (she weighed just over 100 pounds). As Skomal notes, “Her size alone made the stories of her rescues even more sensational.”

The coverage in major national magazine and newspapers, which was echoed in hundreds of smaller publications from coast to coast, made Lewis by far the most famous lighthouse keeper in America, and also one of the most famous women in the nation, up there with the likes of such historical heavyweights as Clara Barton, the pioneering nurse who was christened the “Angel of the Battlefield” for her heroic work during the Civil War, and the novelist Louisa May Alcott, most famous for penning Little Women. Throughout the spring and summer of 1869, Lewis was showered with awards, gifts, and adulation, of which only a partial accounting is offered here. In May the Lifesaving Benevolent Association of New York gave her a silver medal and $100, and the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a resolution in her honor, recognizing her heroism. Soon thereafter the officers and soldiers of Fort Adams collected $218 and gave it to Lewis as a token of their thanks, this on the heels of a gold pocket watch that Adams and McLoughlin had bestowed upon Lewis for saving them. Newport declared July 4, 1869, Ida Lewis Day, and four thousand people gathered to pay her tribute and watch her receive a brand-new rowboat, appropriately named Rescue, which was funded by public donations. Photographers besieged her, and the cartes-de-visite images that resulted were sold far and wide, further cementing her celebrity status. Again similar to Grace Darling, many a suitor wrote to Lewis, asking for her hand in marriage.

By her father’s count, between nine and ten thousand people came to visit America’s new star that summer. Many of them were famous, including Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union general who was reviled in the South and revered in the North for his scorched-earth tactics during the Civil War, and the suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who had earlier that year launched the National Woman Suffrage Association, whose main goal was the passage of a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote. Stanton and Anthony held Lewis up as an example of the great achievements women were capable of, and used her public acclaim and heroism as yet another argument in favor of granting women more equality with men, including, most especially, the right to participate fully in elections. President Ulysses S. Grant also stopped by. According to legend, Grant was so determined to meet the young heroine that he purportedly said, “I have come to see Ida Lewis, and to see her I’d get wet up to my armpits if necessary.” If he actually did say this, he needn’t have worried about getting wet, for he ended up briefly chatting with Lewis at a prearranged meeting on Long Wharf in Newport, where he told her, “I am happy to meet you, Miss Lewis, as one of the heroic, noble women of the age.”

Staying true to the humble dedication of her profession, Lewis didn’t let all this recognition go to her head. In her mind the rescues were simply part of her job. “If there were some people out there who needed help,” she told a reporter later in her life, “I would get into my boat and go to them even if I knew I couldn’t get back. Wouldn’t you?” After her almost unprecedented rendezvous with fame in the summer of 1869, life settled down for Lewis, and that is how she liked it, much preferring tending to the light than being treated as a celebrity, caught in its beam. She remained at Lime Rock until October 23, 1870, when she married a mariner from Bridgeport, Connecticut, one William Heard Wilson, whom she had known for three years. However, the marriage was a fleeting and unhappy one, and after only two years of residing in Connecticut, she left her husband—again defying the conventions of the time—and returned to the lighthouse at Lime Rock.

It was during this time that Lewis’s father died, and her mother was appointed keeper, following the board’s custom of having widows succeed their husbands. It was Lewis, however, who did most of the work in the lighthouse, and she felt slighted by not being chosen keeper. Finally, in 1879 Ida took over from her mother and remained keeper until her death in 1911, thirty-two years later. Lewis’s famous rescue in March 1869, however, was not her last. In 1877 she saved three drunken soldiers who capsized their boat while trying to cross the harbor from the town to Fort Adams. Four years later she performed another rescue that would garner her one of the most prestigious awards of her life.

Late on the afternoon of February 4, 1881, Frederick O. Tucker and Giuseppe Gianetti, both members of the military band at Fort Adams, were in town when they decided to stroll back to the fort over the frozen harbor. Walking side by side, they reached a point called Brenton’s Cove, about halfway between the lighthouse and the fort, where the ice began to get mushy and thin. It had been common knowledge at the fort that the ice in this part of the harbor was dangerous, but either the men were unaware of this or they didn’t care (one observer later claimed that the bandmates were drunk). A few steps further, and both of them plunged through the ice into the freezing water below.

Mother and daughter had been watching the soldiers’ progress from their kitchen window, and when the two men fell through and began screaming, Zoradia allegedly fainted. While Ida’s sister Harriet, tended to their mother, Ida grabbed a clothesline and raced out onto the ice, followed soon thereafter by Rudolph. Reaching the drowning men first, she stood on firmer ice and tossed them the line. Tucker grabbed it, and Lewis, using all her strength to keep from slipping and being pulled in, dragged him onto the ice. By that time Rudolph had arrived, and together he and his sister pulled Gianetti to safety. Neither of the men was able to stand on his own, so the siblings carried them back to the lighthouse, where they recuperated for a while before being taken to the fort’s hospital for treatment.

This rescue received widespread press attention, but more than that, it won Lewis a gold medal for lifesaving from the U.S. Government. The award had been established by an act of Congress in 1874, and was to be given to persons who “endanger their own lives in saving, or endeavoring to save lives from perils of the sea,” with the gold medal being “confined to cases of extreme and heroic daring.” Lewis was the first woman thus honored. Likely just as meaningful as the award was the letter she received from Tucker’s mother a week after the rescue. “Dear good brave woman,” the letter began. “What can I say. What can I do for I cannot thank you half enough on paper for saving the life of my Dear Boy.”

Lewis’s last documented rescue came in 1906, when she was sixty-three. Two of her friends were rowing out to visit her at the lighthouse when one of them stood up and fell in. In what must by then have been pure reflex for her, Lewis immediately got into her skiff and plucked the woman from the water. By the end of her career Lewis was officially credited with rescuing eighteen people from drowning. When she died on October 24, 1911, at the age of sixty-nine, many tributes were offered to her selflessness and bravery. One of the most rousing and patriotic came from a New York Times article, published a week after her death, which used the occasion to set the record straight on a transatlantic rivalry. “The Grace Darling of America? Why do they call Ida Lewis that?” the Times wondered. “Grace Darling is the Ida Lewis of England. … Grace Darling never had a record like this. … The Grace Darling of America? Nonsense. Whom has England, or for that matter, any other country, to show that can match our Ida Lewis?”

More than fourteen hundred people attended Lewis’s funeral. She was buried in Newport’s Common Burying Ground, and despite the incisive pronouncement of the New York Times, when her friends and admirers erected a tombstone in her honor the epitaph read, “Ida Lewis, The Grace Darling of America, Keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse.” The building Lewis loved so much was renamed the “Ida Lewis Lighthouse” in her honor in 1924, making it the only American lighthouse to ever be named after a keeper. The board decommissioned the lighthouse three years later, replacing it with an automatic beacon atop a metal tower. And in 1928 the lighthouse became the clubhouse for Newport’s Ida Lewis Yacht Club, which is connected to shore by a wooden walkway. Appropriately enough, the club’s triangular burgee, or flag, depicts a lighthouse bracketed by eighteen stars, one for each of the lives Ida Lewis saved.

IF IDA LEWIS BECAME FAMOUS in part for the sheer number of rescues she carried out, Marcus A. Hanna distinguished himself among keepers for just one incredible rescue that became a brutal struggle against the elements. Hanna’s story begins with the schooner Australia tied at a wharf in Boothbay, Maine, in the late afternoon of January 28, 1885, waiting to start a scheduled trip to Boston. The cargo consisted of mackerel, dried fish, and guano (seabird droppings, which farmers used as fertilizer). At five o’clock, under fair skies and a light easterly wind, the Australia shoved off, with its three-man crew consisting of Capt. J. W. Lewis, and seamen Irving Pierce and William Kellar. By eleven the Australia was off Halfway Rock, so named because it is halfway between Cape Small and Cape Elizabeth, in Casco Bay. If Lewis took any comfort in seeing the beam of the Halfway Rock Lighthouse, it was overshadowed by his growing concern about the wind-whipped snowstorm that had overtaken his ship.

Lewis decided to take shelter in Portland Harbor, which lay about ten miles northwest of Cape Elizabeth. But as the January weather worsened and the seas mounted, Pierce told Lewis he thought that plan too dangerous, and recommended that they ride out the storm offshore. No sooner had Lewis agreed to this and shifted direction than a mighty gust blew the mainsail to shreds. Lewis reduced the area of the foresail, and began repeatedly sailing the ship closer, and then farther away from the coastline, hoping to roughly maintain the ship’s position until the morning light.

As the crippled ship battled with the elements on the open seas, the temperature, already a frigid four degrees, dropped to ten below. With waves breaking over the bulwarks and flooding the hold, and an ever-thickening layer of ice coating every exposed surface, the men feared that the ship would founder, so they began pitching overboard everything that wasn’t fastened to the deck to lighten its load. Not long after midnight Lewis heard over the roar of the storm the shrill whistle of the fog signal coming from the Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse. Located on a large, rocky headland just southeast of Portland, the lighthouse consisted of two identical sixty-seven-foot cast-iron towers, each housing a second-order Fresnel lens. The station’s steam-powered fog signal was housed in its own building near the shore.

All through the night Lewis and his men struggled to keep the Australia within hearing range of the fog signal. Shortly after dawn on the morning of January 29, they spotted land and the lighthouse’s eastern tower close by. They tried to sail the ship around the cape, but the wind and waves were driving them ever closer to the shore, so they decided that their best chance of surviving was to strand the ship intentionally. A few minutes later the Australia plowed into the rocks near the lighthouse.

BETWEEN MIDNIGHT AND 6:00 A.M., Cape Elizabeth’s head keeper, Marcus A. Hanna, had been on duty running the fog signal. Forty-three years old at the time, Hanna was no newcomer to lighthouses. His grandfather was one of the first keepers at Boon Island, and Hanna spent his first few years of his life at the Franklin Island Lighthouse, in Muscongus Bay, just offshore from Bristol, Maine, where his father had been the keeper. Hanna followed in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps in 1869, becoming the keeper at Pemaquid Point Lighthouse, at the western entrance to Muscongus Bay, and perched on the edge of exquisitely scenic rock ledges made of finely layered gneiss, with alternating black, white, gray, and rust-colored bands that plunge into the sea at gently sloping angles. Four years later, in 1873, Hanna was transferred to Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse.

Of the weather raging outside on that miserable January night, Hanna would later say that it was “one of the coldest and most violent storms of snow, wind, and vapor” he had ever experienced. After being relieved by the second assistant keeper, Hiram Staples, Hanna trudged and at times crawled through the prodigious snowdrifts to get to his quarters, where his wife—and longtime assistant keeper—Louise, was waiting for him. Hanna was suffering from a severe cold, and the six-hour watch combined with his exposure to the storm had left him “weak and exhausted.” All he wanted to do was rest. He put his wife in charge of dousing the lights at sunrise, and then fell into a deep sleep.

At 8:40, after opening the side door to the keeper’s house, Mrs. Hanna saw the Australia’s stationary and tilting masts in the distance. Hurrying back inside, she yelled to her husband, “There is a vessel ashore near the fog signal!” Hanna jumped up, put on his hat, coat, and boots, and rushed as fast as he could through the drifts, heading toward the wreck. On the way he stopped at the fog-signal house, where he found, to his utter amazement, that Staples was unaware of the wreck even though it was barely two hundred yards away.

Staples followed Hanna to the surf’s edge, where they came upon a horrific scene. Pierce and Kellar were in the fore rigging, almost frozen in place. One of them feebly raised his arm, and both cried out for help. As for Captain Lewis, he had been swept overboard soon after the ship stranded, and his mangled body would be found in the surf days later. Hanna recalled that upon seeing Pierce and Kellar, “I felt that there was a terrible responsibility thrust upon me, and I resolved to attempt the rescue at any hazard.”

It was not the first time that Hanna’s sense of duty compelled him to risk all on behalf of his fellow man. During the Civil War, some twenty-two years earlier, Hanna was a sergeant in Company B, Fiftieth Massachusetts Infantry. From late May through early July 1863, Hanna’s unit was part of the Union forces laying siege to the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson, Louisiana, located on the Mississippi River about twenty miles above Baton Rouge. On the morning of July 4, Company B was ordered into a rifle pit—a shallow trench affording cover for infantry firing at the enemy—to support a battery of soldiers from New York.

Marcus A. Hanna.

The men from Company B had already been engaged in an action earlier that day, and hadn’t had time to refill their canteens. As a result they went into the rifle pit with very little water. Since the July weather was sweltering, by afternoon the Massachusetts soldiers were becoming dangerously dehydrated, prompting their lieutenant to give them permission to go on a water run to replenish their canteens. With the nearest spring five hundred yards away, and the enemy in control of the higher ground, such a dash would expose a runner to a veritable turkey shoot of enemy fire. Despite the extreme danger Hanna volunteered to go, but when he asked for assistance, no one stepped forward. Undeterred, Hanna took off with fifteen canteens draped about his body, and notwithstanding the hail of bullets coming from the Confederate lines, he made it to the spring and back unscathed. For this valorous feat, Hanna was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

SINCE THE WRECK OF the Australia was many yards from the shore, Hanna thought that the only way to rescue the men was by throwing them a line. Not having a suitable rope at the lighthouse, Hanna grabbed an ax from the fog-signal building and slogged his way through three hundred yards of deep snow to a pilothouse, planning to hack his way in and retrieve a rope he knew was there. Finding the pilothouse door completely blocked by a huge snowdrift, Hanna ran back to the fog-signal building and told Staples to follow him with a shovel. Staples dug a path to the door, and Hanna broke through with the ax, grabbed the rope, and raced back to scene of the disaster. By this time Nathaniel Staples, Hiram’s fifteen-year old son, had arrived, and Hanna immediately sent him to the closest neighbor’s home to summon help.

Hanna tied a piece of metal to the end of the rope, climbed over the ice-covered rocks into the roiling surf, and repeatedly pitched the rope toward the wreck, while Hiram Staples stood by ready to assist. Every toss landed about ten feet short, and each time Hanna pulled the rope back in, it would begin to freeze and stiffen in his hands, making it even more difficult to use. After nearly twenty attempts Hanna was so numb that he had to retreat to a sheltered area nearby, where he stomped his feet and shook his hands to warm them. He also unraveled and twisted the rope to dislodge its coating of ice. Dismayed by the failure to get the rope to the men, the shivering Staples returned to the fog-signal building, leaving Hanna alone.

As Hanna headed back toward the wreck, a prodigious wave lifted the Australia, hurling it closer to the shore, where, Hanna said, “she came down with a thunderous crash, staving in her whole port side [and] careening her on her beam ends.” Amazingly Pierce and Kellar still clung to the rigging, but their situation was now even more precarious than before. Hanna threw the line, and it landed on the deck between the men, but they couldn’t grab it before it slid into the water. Hanna waded deeper into the frigid surf and threw the line again. This time it hit its mark, and the men secured it around Pierce’s waist. The nearly spent Hanna climbed out of the water and up the icy bank, screaming for help, but nobody heard his cries.

Plunging back into the water, Hanna labored mightily to haul Pierce to shore and up the bank. According to Hanna, “Pierce’s jaws were set, he was totally blind from exposure to the cold, and the expression on his face I shall not soon forget.” Hanna turned his attention to Kellar.

After a couple of failed attempts, Hanna got the line to Kellar, who tied it around his waist and signaled to be pulled in. But Hanna was exhausted. Thoroughly soaked, with hypothermia setting in and his body aching from his exertions and his illness, he doubted he had the strength to drag another man to shore. Still, Hanna began reeling in the line, and just when his endurance was giving out, Nathaniel Staples and two neighbors arrived and helped Hanna pull Kellar in and carry him to the signal house. A few minutes later a towering wave destroyed what was left of the Australia, littering the coast with debris.

The rescuers stripped Pierce’s and Kellar’s frozen clothes, and then gave them dry flannels, hot liquids, and food. Hanna, too, was similarly cared for. With the storm raging yet, and snowdrifts blocking the way, Hanna and the others weren’t able to get Pierce and Kellar to the keeper’s house until the following day, where Hanna and his wife continued nursing them. It was another two days before the roads were cleared enough for Hanna and his assistants to make their way to Portland, the largest city in the state. They returned with doctors from the U.S. Marine Hospital, who transported Pierce and Kellar back to the city, where they were successfully treated for severe frostbite and shock.

On April 29, 1885, less than two months before the Statue of Liberty arrived with great fanfare in New York Harbor on board the French naval ship Isère, the government awarded Hanna a Gold Lifesaving Medal, the same honor Ida Lewis had received, for his heroic conduct on that storm-lashed January day. Thus Marcus A. Hanna became the only person in American history ever to have won both the Congressional Medal of Honor and its civilian counterpart.

THE EXTENT TO WHICH KEEPERS rendered assistance to people in distress on the water became much clearer with the advent of the Lighthouse Service. Each year the Lighthouse Service Bulletin briefly detailed incidents in which lighthouse service employees, mainly keepers, saved lives or property. In the service’s first decade alone, more than 1,234 such incidents were recorded. But it wasn’t only keepers who came to the rescue. Sometimes lighthouses did too, as was the case at Bolivar Point in Texas and Kilauea Point in Hawaii.

Just after sunrise on Saturday, September 8, 1900, a real-estate agent and insurance broker named Buford T. Morris awoke in his weekend home in Galveston, Texas, looked out the window, and was greeted by a wondrous sight. “The sky seemed to be made of mother of pearl,” he later recalled. “Gloriously pink, yet containing a fish-scale-effect which reflected all the colors of the rainbow. Never have I seen such a beautiful sky.” This surreal morning scene would prove a potent and ominous sign, as a short while later these brilliant colors faded, the sky darkened, and rain began to fall. A killer of massive proportions was on the way.

Nobody in Galveston was particularly worried about the weather that morning. Although a major storm had dumped more than two feet of rain in Cuba over the past week, roared over the tip of Florida, and then planted itself in the Gulf of Mexico, causing widespread damage along the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts, the U.S. Weather Bureau’s forecasters didn’t think the storm was worthy of being called a hurricane, nor did they think Galveston would be hit too hard. Minor flooding and strong winds, perhaps, but nothing the city hadn’t handled before.

By late morning, however, the weather had gotten much worse. People living on Bolivar Peninsula, a long, slender ribbon of sand that lies directly across a ship channel from Galveston, were growing quite concerned. With winds gusting up to fifty miles per hour, and the Gulf waters, which had already swept over some low-lying areas, rising fast, some residents who had been displaced from their homes went to the Bolivar Point Lighthouse at the peninsula’s tip seeking refuge. If any structure in the area could withstand the storm’s fury, they thought, it would be the lighthouse.

Built in 1872 to replace the tower that had been torn down during the Civil War, the new Bolivar Point Lighthouse rose 117 feet above sea level and had a cast-iron shell with a brick-lined interior. By noon the head keeper, Harry C. Claiborne, and his assistants had welcomed more than one hundred storm refugees into the lighthouse and closed the door. The water at the base of the tower was already a few feet deep, and the new occupants spread themselves out on the iron stairs that wound up the center of the lighthouse, sitting on alternating steps.

Around the time Claiborne closed the lighthouse door, another drama was playing out nearby. The train coming from Beaumont, Texas, on its way to Galveston was creeping slowly over the flooded tracks as it approached the end of the line, about a quarter mile from the lighthouse. At that point the locomotive and its two coaches, filled with ninety-five passengers, were supposed to be loaded onto the Charlotte M. Allen, a ferry that would take them the two miles across the ship channel to Galveston. As the passengers watched with growing apprehension, the Charlotte M. Allen tried to battle its way from Galveston to the boat slip at Bolivar Point, but was having no luck fighting the storm. Towering swells broke over the ferry’s bow, and the whipping winds blew it off course. Finally the ferry captain gave up, turned the Charlotte M. Allen around, and headed back to Galveston.

Bolivar Point Lighthouse, circa early twentieth century.

The water on the tracks had continued rising and was now near the top of the train’s wheels. Hoping to return to Beaumont, the conductor ordered the engineer to reverse engines, but as the train began moving backward, water rushed into the coach compartments. When the train briefly stopped, ten passengers jumped off. They had been looking at the sturdy lighthouse in the distance and thought they would be safer in there than on the train. As they waded through the rushing water toward what they hoped would be their tower of salvation, the train began moving again and was soon out of sight. Upon reaching the lighthouse, the passengers yelled and knocked on its door, and Claiborne let them in. They would be the last people to enter.

THE WEATHER BUREAU HAD been drastically wrong. The storm that hit the Galveston area was what would register today as a category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Sampson Scale (developed in the late 1960s), with sustained winds of more than 130 mph, and gusts reaching as high as 200 mph, strong enough to rip the bark off trees. The bureau’s mistake was not all that surprising, however, given the rudimentary nature of weather forecasting in 1900, in addition to the fact that hurricanes are notoriously fickle, and have since time immemorial, and right up to the present, thwarted people’s ability to predict their violent course. The failed forecast only added to the frustrations and fears of the 125 people crammed into the lighthouse, who would have to ride out the hurricane together.

That night, as the tower swayed from side to side, Claiborne tended to the light, for even in this calamitous weather he thought there might be mariners on the water who needed the beacon’s aid. Holding onto the iron handgrips in the lantern room to keep from being thrown off his feet, he kept the light burning. Claiborne had stocked up on supplies just before the storm in case the flooding was worse than anticipated, so he was able to feed the refugees. Providing fresh water, however, proved more of a challenge. Volunteers leaned out onto the catwalk surrounding the lantern room, holding buckets aloft to catch the rain, yet the spume of the waves crashing into the tower rose so high that the first few bucketfuls were salty, not fresh. After more attempts, however, drinkable water was obtained, and the buckets were passed to the thirsty people below.

The next day, when the floodwaters receded and the lighthouse’s iron door was finally opened, the people streamed gratefully out into the bright sunshine only to be greeted by a gruesome sight. Strewn around the tower’s base were a dozen corpses. In fact, death was everywhere. The Great Galveston Hurricane had leveled thousands of buildings and claimed at least six thousand lives, with some estimates rising as high as ten thousand. It remains the worst natural disaster in American history. Among the dead were the eighty-five passengers who remained on the train instead of heading to the lighthouse. Somewhere along its way back to Beaumont, the train and everyone on board had been engulfed by the hurricane.

Fifteen years later the Bolivar Point Lighthouse would again live up to its reputation as a savior. On the afternoon of August 16, 1915, as another hurricane bore down on the Texas coast, sixty people who lived in the vicinity of Bolivar Point rushed to the lighthouse to find refuge. Claiborne, who was still the head keeper, welcomed them in. That night, according to the assistant keeper, James P. Brooks, “The big tower shook and swayed in the wind like a giant reed.” A little after nine, the tower’s violent motion damaged the mechanism that rotated the lens, forcing Brooks to turn the lens by hand. By ten o’clock the tower was vibrating so wildly that even this was impossible, so Brooks secured the lens to keep it from falling off its pedestal and left the light burning. When he climbed down the stairs, he confronted another problem. Wind had blown open the iron door, allowing water to rush in and fill the bottom of the tower to a height of five feet. Brooks grabbed a rope and jumped in, and despite being thrown about and badly bruised, he managed to fasten the door shut.

The water receded slowly the following day, and the wind was still blowing hard, forcing people to stay in the tower another night. Because there was no more kerosene, the lighthouse was dark for the first time since it was built. Finally, on the morning of August 18, their ordeal over, the sixty famished refugees emerged from the lighthouse.

IN THE CASE OF the Kilauea Point Lighthouse twelve years later, it wasn’t refugees from a hurricane who were saved, but rather a plane and its two-man crew. Just before 7:00 a.m. on June 27, 1927, U.S. Army lieutenants Lester J. Maitland and Albert F. Hegenberger climbed into their new Fokker C-2 Wright 220-horsepower trimotor transport plane, named the Bird of Paradise, hoping to become the first aviators to fly nonstop from California to Hawaii. Their attempt meshed perfectly with the tenor of the times. This was an era early in the evolution of manned flight when pilots and plane manufacturers were constantly pushing themselves to fly farther and faster, to prove to the public at large the great military and commercial potential of aviation. A little more than a month before the Bird of Paradise’s flight, Charles Lindbergh had made his own bit of history when he flew the single engine 220-horsepower Spirit of St. Louis 3,600 miles from Roosevelt Field on Long Island to Le Bourget Field in Paris, thus completing the first solo transatlantic flight and earning the moniker “Lucky Lindy”—although luck in fact had little to do with it, since his preparation and training for the flight had been meticulous.

The Bird of Paradise had a wingspan of seventy-two feet, and on that June morning it carried 1,120 gallons of gasoline and tipped the scales at fourteen thousand pounds, including all the equipment on board and the weight of its two occupants. The plane took off from Oakland airport at 7:09, with Maitland as pilot and Hegenberger as navigator. Their flight plan had them covering roughly 2,400 miles of ocean, and landing at Wheeler Field on the island of Oahu sometime in the early morning hours of the following day. Critical to their success would be Hegenberger’s ability to keep them on course, because if they drifted more than 3.5 degrees off course in either direction, they would completely miss the islands.

Unfortunately the so-called Murphy’s law came into play: Almost everything that could go wrong did. Within an hour and a half of taking off, all their fancy navigational equipment failed, including the radio beacon receiver and the induction compass, which uses the earth’s magnetic fields to determine direction. The smoke bombs they had brought with them to measure drift couldn’t be used because of the high winds and rough seas. Rather than despair, however, Hegenberger, who was considered one of the army’s best navigators, improvised. To measure drift he used an ordinary compass and tracked the movement of the whitecaps on the waves, which he could see out of the trapdoor in the floor of the plane. He also relied on dead reckoning to determine the plane’s location.

At 10:00 p.m. Maitland and Hegenberger decided to get above the heavy cloud cover to use celestial navigation, which led to another problem. As they approached eleven thousand feet, the center engine’s cylinders and carburetor intake iced over, causing the center engine to cut out. It wasn’t until the plane descended to three thousand feet that the engine revived, restoring the plane’s full power. Still wanting to use the stars to navigate, Maitland took the plane slowly up to seven thousand feet, as high as he could go and avoid icing. This allowed Hegenberger to locate Polaris, the North Star, giving him added confidence that they were on course.

The Bird of Paradise coming in for a landing at Wheeler Field in the early morning hours of June 28, 1927.

A little after 3:00 a.m. on June 28, Maitland said he “saw a light which was more yellow than a star,” far off in the distance, to the left of the plane. At first he thought it was a steamer, but then, with a profound sense of relief, he realized that it was the beam from the Kilauea Point Lighthouse, a fifty-two-foot-tall steel-reinforced concrete tower located near the edge of a lofty promontory on Kauai, the northernmost island in the Hawaiian chain. Kauai was only about seventy-five miles from their destination on Oahu, but because of the rain, and his concern about flying over the mountains of Oahu in the dark, Maitland circled Kauai until the sun rose and then finally headed to Wheeler Field. Nearly out of fuel, the Bird of Paradise landed at 6:29 a.m.

There is no way of knowing what would have happened if Maitland hadn’t seen the lighthouse’s beam. Beyond Kauai there is nothing but ocean for thousands of miles. Had they flown past Kauai in the darkness and kept going, the plane would have run out of fuel and plunged into the water. According to some accounts Maitland and Hegenberger realized that they were north of their course, and had they not seen the lighthouse about when they did, they were planning to circle around to the south, which might or might not have resulted in them sighting one of the islands, and ultimately finding Wheeler Field.

These what-ifs notwithstanding, there is no doubt that the lighthouse’s beam was instrumental in the success of the flight. As the August 1, 1927, issue of the Lighthouse Service Bulletin noted, “These aviators picked up the light at a distance of about 90 miles, soon recognizing it as a lighthouse and subsequently identifying it by its flashes. If Lieutenants Maitland and Hegenberger had not picked up Kilauea Point Light, they might have passed the Hawaiian Islands, missing them entirely.” In a private conversation Maitland assigned the lighthouse a more definitive starring role. At a reception held for the aviators shortly after they landed, he told a high-ranking Lighthouse Service official that “the Kilauea Lighthouse had saved his life.”