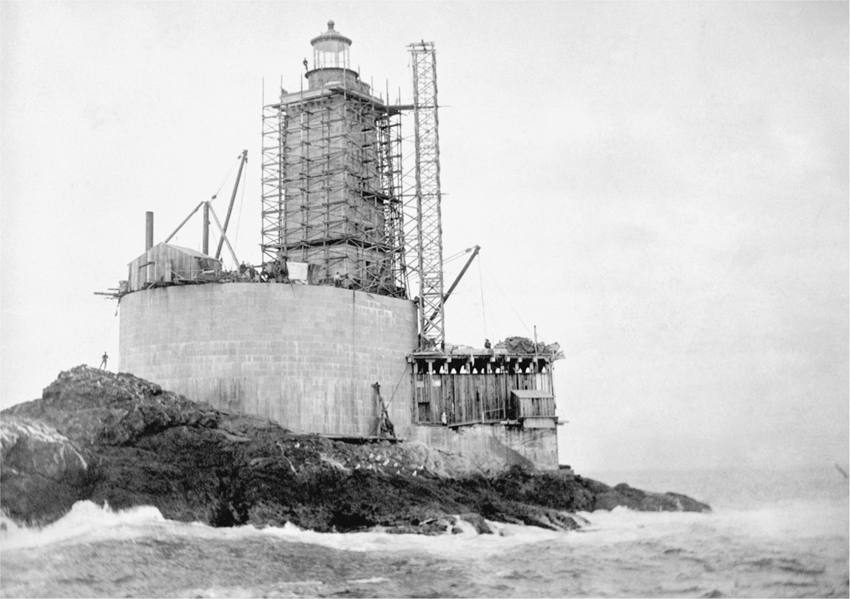

Scaffolding around the St. George Reef Lighthouse toward the end of construction, 1891.

MARVELS OF ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scaffolding around the St. George Reef Lighthouse toward the end of construction, 1891.

EVERY LIGHTHOUSE POSES A UNIQUE CHALLENGE TO ITS ARCHITECTS and builders. The design must be sound, the site properly prepared, the materials of high quality, environmental obstacles overcome, and the engineers and workmen up to the task of executing the job skillfully. But not all lighthouses are equal. Some posed challenges so great that the resulting structures can truly be considered marvels of engineering and construction. Minot’s Ledge, Tillamook Rock, and St. George Reef are three American lighthouses deserving that appellation.

In fact there were actually two Minot’s Ledge Lighthouses, one completed in 1849 and the other—the true marvel—only eleven years later, in 1860, when Lincoln was first elected. But to understand how the second one came to be built, it is necessary tell the story of the first, as well. That tale begins, as so many lighthouse stories do, with disasters at sea.

About two miles off the coast of Cohasset, Massachusetts, and nine miles southeast of the mouth of Boston Harbor, lies a cluster of rock ledges that had terrorized mariners for hundreds of years. The most notorious of these so-called Cohasset Rocks is Minot’s Ledge, named after the prominent Boston merchant George Minot, who lost a ship there in the mid-1700s. Minot’s Ledge was particularly treacherous because most of the time it was completely submerged. Only at low tide could it be seen, and then only a small part of the ledge was visible just above the surface.

In 1838 the Boston Marine Society became gravely concerned about the many ships and lives claimed by Minot’s. Accordingly, its leaders began lobbying the federal government to build a lighthouse on the ledge, but their pleas to Congress, then bent on retrenchment and more interested in westward expansion, fell on deaf ears. Then IWP Lewis, the reformer who led the charge against the continued use of Winslow Lewis’s mediocre “magnifying and reflecting lantern” and for the adoption of Fresnel lenses, joined the discourse. In his scathing 1843 report on the lighthouses of Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, IWP echoed the society’s call for action. After listing forty shipwrecks that had occurred in the vicinity of Minot’s Ledge in just the previous nine years, Lewis argued that a lighthouse “is more required [there] than on any part of the seaboard of New England.” As for the feasibility of building a lighthouse in such an exposed, wave-swept location, Lewis was confident it could be done. “Though formidable difficulties would embarrass the undertaking,” he concluded, “they were not greater than such as were successfully triumphed over by a ‘Smeaton’ or a ‘Stevenson.’ ”

The Smeaton to whom IWP referred was the British engineer John Smeaton, a legend in the world of lighthouse construction for having built the third Eddystone Lighthouse, located off Plymouth, England, in the late 1750s. The first Eddystone Lighthouse—Henry Winstanley’s creation—was destroyed by the “Great Storm” in 1703, and the second burned to the ground in 1755. This set the stage for the third effort, spearheaded by Smeaton, who decided to build his lighthouse out of stone. The resulting edifice was a tour-de-force of eighteenth-century engineering, unlike any structure that had come before. Smeaton had designed the stone blocks in each layer, or course, of the tower to be cut so that they dovetailed with one another, essentially fitting them together like a jigsaw puzzle. Then, to connect each course with the ones above and below, he inserted oak pins into holes drilled in the blocks. Finally, instead of employing a conical tower, he designed it to resemble an oak tree, which, he noted, is “broad at its base, curves inward at its waist, [and] becomes narrower towards the top.” Smeaton’s rationale, based on a solid understanding of nature, was simple: “The English oak tree withstands the most violent weather conditions,” he said, and “we seldom hear of a mature oak being uprooted.” All these features helped to create an astonishingly sturdy structure that could survive not only the fiercest pummeling from the sea, but also wind gusts from the most vicious storms. Upon its completion in 1759, Smeaton’s triumph, hailed throughout the European and colonial worlds of the mid-eighteenth century, became the model for anyone building a lighthouse in a wave-swept location.

One such inspired individual was the Scottish engineer Robert Stevenson, patriarch of the famed lighthouse Stevensons. In the early 1800s Britain’s Northern Lighthouse Board tasked him with building a lighthouse on Bell Rock, a sandstone reef located about eleven miles off Scotland’s craggy east coast and completely submerged most of the time. Stevenson closely followed Smeaton’s design, and the Bell Rock Lighthouse, first lit on February 1, 1811, in the waning years of the Napoleonic era, ranks as one of his masterpieces.

By referring to “a Smeaton or a Stevenson,” IWP was thus throwing down the gauntlet to the American congressmen who were the target audience for his report, by playing to their patriotism. If these British fellows could build lighthouses on wave-swept locations, why, wondered Lewis, couldn’t American engineers do the same at Minot’s Ledge?

It wasn’t until March 1847 that Congress, largely preoccupied with the war against Mexico, was convinced, and ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers to build a lighthouse on the ledge. The corps immediately sent an engineer, forty-six-year-old Capt. William Henry Swift, to Cohasset to evaluate the site and propose a plan. Swift, who was born in Taunton, Massachusetts, and already had a fairly distinguished career as a surveyor, coastal engineer, and canal builder, first had to decide where to put the lighthouse. There is both an inner and an outer Minot’s Ledge, separated by about three hundred feet, and Swift chose the outer because the rock at that location was much more solid and had fewer seams than the one at inner Minot’s.

Swift now had to decide what type of lighthouse to build. He didn’t have much space. At low tide the only visible part of the ledge was roughly twenty-five feet in diameter. While Swift believed it would be possible to build a stone tower on such a slender foundation, he estimated that it would cost between $250,000 and $500,000. Given the great expense, he didn’t think a stone tower like Smeaton’s or Stevenson’s was a viable option. But that didn’t concern him because he had a much cheaper alternative in mind, which he thought would work just as well.

His plan at its most basic called for placing the keeper’s quarters and the lantern room far above the waves, supported by stiltlike iron piles embedded in the ledge. Not only would an iron-pile lighthouse be more economical, costing between twenty and fifty thousand dollars, but Swift also believed that it could withstand the elements as well as a lighthouse made of stone. Here he used the same argument that American engineers would use in later years to support the construction of iron skeleton lighthouses offshore; namely, that the lighthouse’s open structure offered little resistance to wind and waves, which could pass right through and around the piles. Swift’s bosses at the corps approved his plan and told him to proceed.

The main obstacle to the project was time. Construction could only take place from spring to early fall, since the months of Massachusetts’s winter were far too cold and stormy. Within that span, work could only proceed when the ledge was exposed around low tide—a mere two to three hours a day. And even that was contingent upon the vagaries of the Atlantic, with its ever-shifting mood. If the waves were too high or, worse, a storm was closing in, work quickly derailed. To maximize the amount of work time, the contractor moored a schooner near the site, weather permitting, and had his men sleep on board so that they could reach the ledge immediately when the conditions were right.

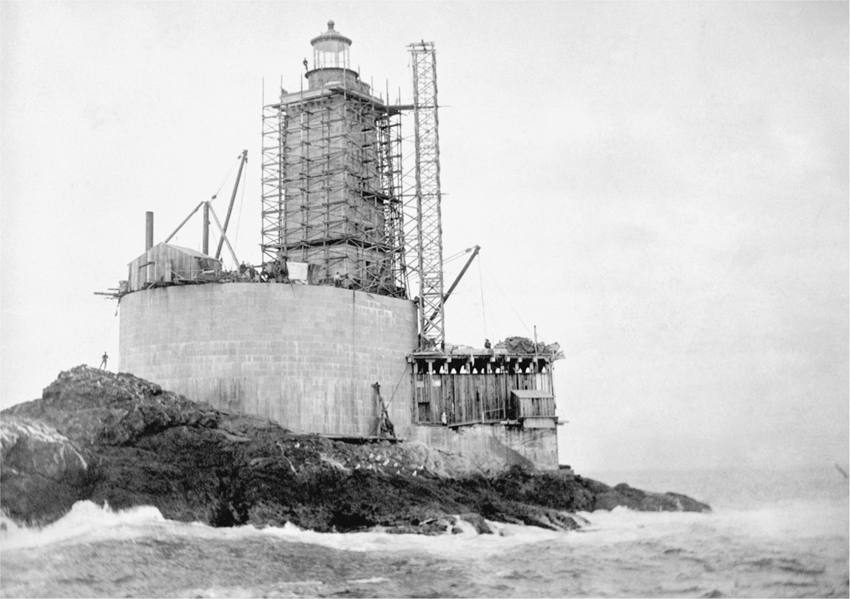

Drawing of the first Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse, circa 1849.

Work commenced in July 1847 and finished just over two years later in October 1849. The resulting lighthouse cost $39,500 and was seventy feet high. The keeper’s quarters sat on a fourteen-foot-wide iron platform fifty-five feet above the ledge. Nine iron piles held the platform aloft, and each pile was cemented into five-foot-deep holes drilled into the rock. For added stability the piles were braced horizontally and diagonally with iron rods. The lantern room sat on top of the keeper’s quarters, and beneath the quarters, enclosed within the piles, was a storeroom for oil, provisions, and other supplies.

Henry David Thoreau, while a passenger on a sailboat heading from Provincetown to Boston, first saw the lighthouse in the summer of 1849, a few months before its completion. “Here was the new iron lighthouse,” he wrote, “then unfinished, in the shape of an egg-shell painted red, and placed high on iron pillars, like the ovum of a sea monster floating on the waves,—destined to be phosphorescent. As we passed it at half-tide we saw the spray tossed up nearly to the shell. A man was to live in that egg-shell day and night.” Actually three men would live at the lighthouse—Isaac Dunham, who was appointed keeper in late 1849, and his two assistants. The men rotated, with two being on duty while the third was ashore.

Dunham lit the lighthouse’s lamps for the first time on January 1, 1850, and soon thereafter his worries began. “A tremendous gale of wind,” he wrote in his log on January 8, came over the water, and “it seems as though the lighthouse would go from the rock.” From here on out Dunham’s log is punctuated by entries that show a man increasingly in fear for his life. On March 31, after enduring numerous bouts of bad weather, Dunham thought it a miracle that he had survived the winter: “For this month ends, and I thank God that I am yet in the Land of the Living.” But April storms brought renewed terror. Early on April 6 Dunham wrote that another gale produced “an ugly sea which makes the lighthouse reel like a drunken man—I hope God will in mercy still the raging sea—or we must perish.” Later that same day he added, “We cannot survive the night—if it is to be so—O God receive my unworthy soul for Christ sake for in him I put my trust.” Yet the gale ended, and Dunham lived another day.

Even the kitten Dunham brought as a companion was rattled by the storms, driven mad by the precarious conditions in the lighthouse, skittering about the watch room in a panic when the tower shook. The kitten’s tenure didn’t last long. On a day when the seas were calm and the sun was shining brilliantly in a cloudless sky, Dunham thought the frightened feline’s frayed nerves would be soothed by a walk around the gallery platform outside the watch room, where it could get some fresh air. Dunham opened the door to the gallery and called to the kitten, which promptly raced up the ladder into the watch room, then circled the room twice, each time passing right by the open door. On its third circuit, the clearly addled kitten rushed out the door and kept going, across the platform and then over the edge into midair. When Dunham reached the gallery railing and looked down, he saw the kitten barely moving on the ledge far below. The next wave, however, swept it off the rock, thereby ending its short and frazzled life.

Having survived that most punishing winter, Dunham urged his superiors in the spring of 1850 to reinforce the lighthouse, claiming that if this were not done soon, the next major storm would surely be the end of it. Dunham’s request was ignored, and Swift dismissed his concerns, reiterating his great faith in the ability of the lighthouse to handle the worst weather imaginable. Rebuffed, and unwilling to put his life on the line during what was sure to be another tempestuous New England winter, Dunham resigned his post on October 7, 1850, and his two assistants followed suit.

John W. Bennett replaced Dunham, and hired two new assistants, Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine. Prior to his departure Dunham shared his concerns about the lighthouse with a great number of people, and the safety of Minot’s had become a lively topic of conversation in and around Boston and Cohasset. Bennett too had heard the scuttlebutt, but rather than take any heed of what Dunham said, he disparaged the former keeper as an alarmist.

All it took, however, was one good nor’easter in the late fall of 1850 for Bennett to aver that Dunham was right. As soon as the storm had passed, and lighthouse ceased its violent shaking, Bennett wrote to the customs collector in Boston, with a plea identical to Dunham’s: Strengthen the lighthouse or else. Again no action was taken.

Three days before Christmas another gale walloped Minot’s, sending Bennett into a tailspin. At the height of the two-day tempest he wrote an anguished letter to the editor of the Boston Daily Journal that he feared might be his last:

At intervals an appalling stillness prevails, creating an inconceivable dread, each [of us] gazing with breathless emotion at one another; but the next moment the deep roar of another roller is heard, seeming as if it would tear up the very rocks beneath as it burst upon us—the lighthouse, quivering and trembling to its very centre, recovers itself just in time to breast the fury of another and another as they roll in upon us with resistless force. … Our situation is perilous. If any thing happens ere day dawn upon us again, we have no hope of escape. But I shall, if it be God’s will, die in the performance of my duty.

To make sure the letter got out, even if he didn’t, he placed a copy of it in a bottle and threw it into the sea.

Like Dunham, Bennett survived, and when his letter appeared in the Journal a few days later, it precipitated a lengthy response from Swift, which appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser. The captain defended the lighthouse both in terms of its economy as compared with a stone tower, and of its safety. In the end, he wrote, “Time, the great expounder of the truth or the fallacy of the question, will decide for or against the Minot; but inasmuch as the light has outlived nearly three winters, there is some reason to hope that it may survive one or two more.” Swift was too optimistic or perhaps too prideful of his own creation, for the winter of 1850–51 would be the lighthouse’s last.

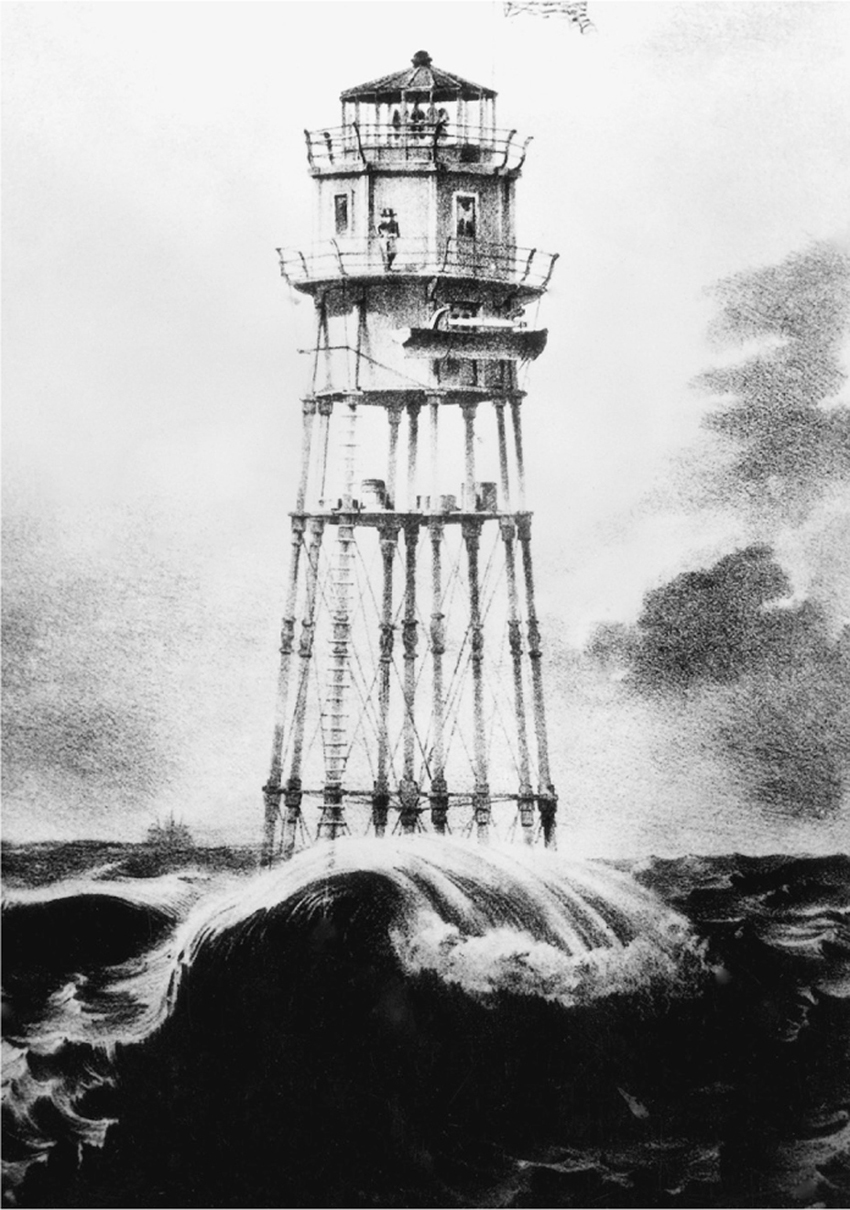

From April 14–17, 1851, while Bennett was ashore, leaving Wilson and Antoine behind, a historic storm slammed the Massachusetts coast, generating some of the highest tides ever seen in the area, washing out train tracks, flooding buildings, sweeping away houses, and causing serious damage all along the shore. The worst time for Wilson and Antoine came on the evening of the sixteenth. Believing that the lighthouse would not make it through the storm, they put another note in a bottle, which was miraculously found by a Gloucester fisherman the next day. It read, “The lighthouse won’t stand over to night. She shakes 2 feet each way now.”

Exactly when the lighthouse lost its battle with the elements is not known. A few people on shore reported seeing the faint beams of light as late at 10:00 p.m., and the lighthouse’s six-hundred-pound fog bell could still be heard faintly ringing three hours later. Soon thereafter, however, Minot’s Lighthouse was completely rent from the ledge and thrown like a matchbox toy into sea, leaving behind only the bent stubs of the pilings, sheared off a few feet above the rock. When Bennett arrived at the beach at 4:00 a.m., evidence of the disaster was strewn about. He found remains of the keeper’s quarters and the lantern room, as well as some of his own clothes. The battered bodies of the two assistant keepers were recovered later.

Destruction of Minot’s Lighthouse, from Gleason’s Pictorial, 1851.

There were recriminations all around. Swift predictably blamed the keepers for modifications they had made to the lighthouse, including adding a platform beneath the storeroom to hold supplies, which he said only created another surface for the waves to pound against. Bennett, for his part, argued that the lighthouse was poorly designed, too heavy for the small base upon which it stood, and that the iron used in its construction was of inferior quality.

Regardless of who deserved blame, the lighthouse was irrevocably gone, and mariners were once again without a guiding light on the ledge, but not for long. A few weeks after the storm, a group of Boston insurance companies sent a steamship fitted out with a light to be moored off the ledge. That ship was soon replaced with a lightship supplied by the Department of the Treasury. Still, this was seen as a temporary fix. As the number of wrecks in the vicinity of Minot’s continued to mount, the government decided that another lighthouse would have to be built on the same spot, this time out of stone.

GEN. JOSEPH G. TOTTEN, chief of the Army Corps of Engineers and a member of the Lighthouse Board, designed the new lighthouse after studying the work of Smeaton and Stevenson. But rather than propose a tapering tower shaped like an oak, Totten went with a conical form, believing it would be equally sturdy. He then tapped Capt. Barton S. Alexander, a seasoned engineer, to oversee construction. On June 20, 1855, Alexander sent men to Minot’s to clear the rock of seaweed and mussels, and to remove the vestiges of the iron piles from their holes. On July 1 he and his construction team landed on the ledge for the first time. Before beginning to work, Alexander rallied his troops. He told them that the task ahead would be long and arduous, and full of unforeseen obstacles and delays, but he was confident that they would carry it through until the lighthouse was completed, “whether it be two years or ten.”

As with the iron-pile lighthouse, construction took place from spring to early fall. The most difficult challenge was preparing the ledge. The base of the lighthouse was to be thirty feet across, but at low water only twenty-five feet of the ledge was exposed. This meant that some of the rock that had to be leveled was perpetually underwater, and the rest exposed so briefly that the men had only a very limited amount of time to accomplish their work. As Alexander noted, “There had to be a combination of favorable circumstances to enable us to land on the Minot rock at the beginning of that work—a perfectly smooth sea, a dead calm, and low spring tides. … Frequently, one or the other of the necessary conditions would fail, and there were at times months … when we could not land there at all.”

Since the men could work on the ledge at most only a few days a month, Alexander had them do double duty to keep them busy. When they weren’t on the ledge, they were on shore at Government Island, a staging area in Cohasset, painstakingly cutting, chiseling, drilling, and hammering the stone building blocks for the lighthouse, each of which weighed about two tons and were made from the finest-grained granite that had been quarried in nearby Quincy, Massachusetts, and then transported to Government Island by ship.*

Alexander employed two rowboats to get himself and his men to Minot’s. According to one of the men, they remained vigilant to ensure that they lost no time on the rock. “We would watch the tide from the cove,” he said, “and just as soon as the ebb had reached the proper stage we would start out with it, and at the moment a square yard of ledge was bare of water, out would jump a stone cutter and begin work. Soon another would follow, and as fast as they had elbow room others still, until the rock would resemble a carcass covered with a flock of crows.”

In 1856 wrought-iron piles twenty feet long were inserted into holes formerly used by the iron-pile lighthouse. These would later be incorporated into the stone tower, serving to bolt it to the rock. The piles were bound together at the top by an iron frame, creating a scaffold from which ropes were strung to give the men something to grab onto when waves threatened to wash them off their feet. Even with the ropes, however, men were sometimes caught off guard and swept into the water. That is why Alexander hired the aptly named Michael Neptune Braddock to serve as a lifeguard, watching the men from a boat while they worked, and diving in to rescue them when necessary.

The difficult project was making good progress until it encountered a major setback on January 19, 1857. During a nor’easter the bark New Empire crashed into the outer ledges of Cohasset before running aground not far away. Once the storm died down, Alexander looked toward Minot’s and was shocked by what he didn’t see. His carefully crafted and, he thought, exceptionally strong iron scaffold, piles and all, was gone. He assumed it had been swept away by the storm, and for the first time he questioned the wisdom of the project. “If tough wrought iron won’t stand it,” he said, “I have my fears about a stone tower.” But his despair evaporated when it was determined that the New Empire, not the weather, had dislodged the scaffold when it struck the ledge.

With renewed confidence Alexander sent his men to Minot’s in the spring of 1857. They reinserted iron piles into the ledge and recut some of the rock that was damaged during the collision. By the end of that season the men had laid the first four foundation stones, each of which was affixed to the rock with long iron bolts and the finest quality Portland cement. The following year the men finished the foundation and brought the tower up to its sixth course.

The tower’s granite blocks were cut to exacting specifications. Each one was dovetailed to fit snugly into the blocks on either side of it, and holes were drilled into the top and bottom of the blocks, into which were inserted galvanized iron bolts that firmly held the different courses together. To ensure that everything fit together perfectly, Alexander had his men assemble the courses at Government Island before ferrying the blocks to the ledge, where they were lowered into place by a derrick attached to an iron mast running up through the center of the structure. To further bind the blocks to one another, and the iron bolts to their holes, cement was used throughout.

Much of the early work on the ledge was done beneath the level of the lowest low tide, but Alexander devised a creative way to do some of this under relatively dry conditions. He had his men use hundreds of sandbags to build temporary cofferdams surrounding the work area. Once the sandbags were in place, the water within was bailed out and large sponges were employed to mop up any seepage. In this manner a small area would be exposed for a short period, during which time the men could level the uneven rocky ledge and put the stones in place.

This method, however, could not be used all the time, and some of the leveling work was done with specially designed hammers and chisels when the ledge was covered with as much as three feet of water. By the same token, some of the lowest stones in the tower had to be laid in the water. This posed a problem, since the water swirling around the stones would wash away the cement before it could properly set. To overcome this difficulty another creative technique was developed. A large piece of thin muslin was laid out on a platform on the ledge. The muslin was slathered with cement, and then the stone was placed on top. Cement was then spread on the sides of the stone, and the remaining cloth was folded up to cover the cement. After about ten minutes the cement began to set, and then the stone was lowered into position. The muslin envelope not only shielded the cement from being washed away by the water, but it was also thin and porous enough so that the cement could ooze through the cloth, allowing the stone to bond to those below and next to it.

On October 2, 1858, a grand ceremony held in Cohasset commemorated the laying of the lighthouse’s cornerstone. The illustrious crowd—diverted from the pre–Civil War tensions that already consumed Boston—included the city’s mayor, many city officials, presidents of insurance companies, and shipowners. To assure the audience that history would not be repeating itself, Alexander told them that there was no comparing the lighthouse then being built on the ledge with the earlier one. “A light-house of iron was erected here some years ago,” he said, “whose fearful fate all may remember. Now again we are erecting a light-house here, but this time of granite, granite piled on granite, granite to build upon, the earth’s substructure; granite engrafted and dovetailed in the foundation, and granite the whole.”

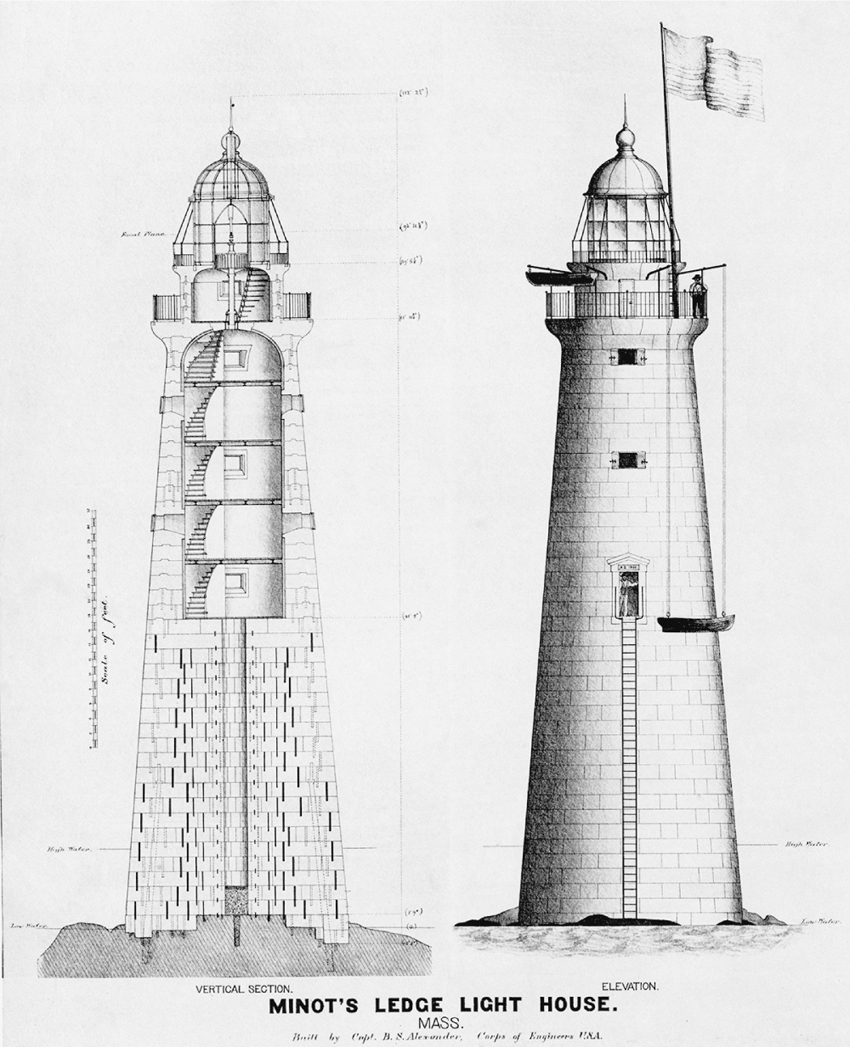

Schematic of second Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse.

The final speaker of the day was the famed orator Edward Everett, a former secretary of state and Massachusetts governor, representative and senator, who took this opportunity to use the lighthouse as a metaphor for the Union he so desperately wanted to keep together, but which was already exhibiting the severe political strains that would ultimately tear it asunder during the Civil War. “Let us remember,” he said, “that in the event of [the rupture of the Union] … the protecting power which now spreads its aegis over us, East and West, North and South, will be forever gone;—and as you have told us, sir, that the solid foundations of the structure you are rearing are linked and bolted together with dove-tailed blocks of granite and bars of galvanized iron, so as never to be moved, so may the sister States of this Union be forever bound together, by the stronger ties of common language, kindred blood, and mutual affection.”

By the end of the 1859 season the men laid stone up to the thirty-second course, sixty-two feet above low water. On June 29, 1860, almost exactly five years to the day from when construction had commenced, the last of the 1,079 granite blocks was added to the tower. The following months were spent putting up and fitting out the lantern room, and on November 15, less than two weeks after Lincoln was elected president, the lighthouse was illuminated for the first time.

The impressive structure soared 114 feet from the ledge to the top of the lantern. The bottom forty feet were comprised of solid granite, with the exception of a three-foot-wide cistern for potable water. Higher up in the tower were the storeroom, keepers’ quarters, workroom, watch room, and finally the lantern room, which originally housed a second-order Fresnel lens exhibiting a fixed white light. Costing three hundred thousand dollars, Minot’s was the most expensive lighthouse built in the United States up to that point.

Totten and Alexander had lived up to the standards set by Smeaton and Stevenson. As the highly respected nineteenth-century Army engineer John Gross Barnard observed, Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse “ranks, by the engineering difficulties surmounted in its erection, and by the skill and science shown in the details of its construction, among the chief of the great sea-rock lighthouses of the world.” Completed in the waning months of peace before the outbreak of the Civil War, Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse became both a symbol and a dramatic sight on its own. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, observing it for the first time, said that it “rises out of the sea like a beautiful stone cannon, mouth upward, belching forth only friendly fires.”

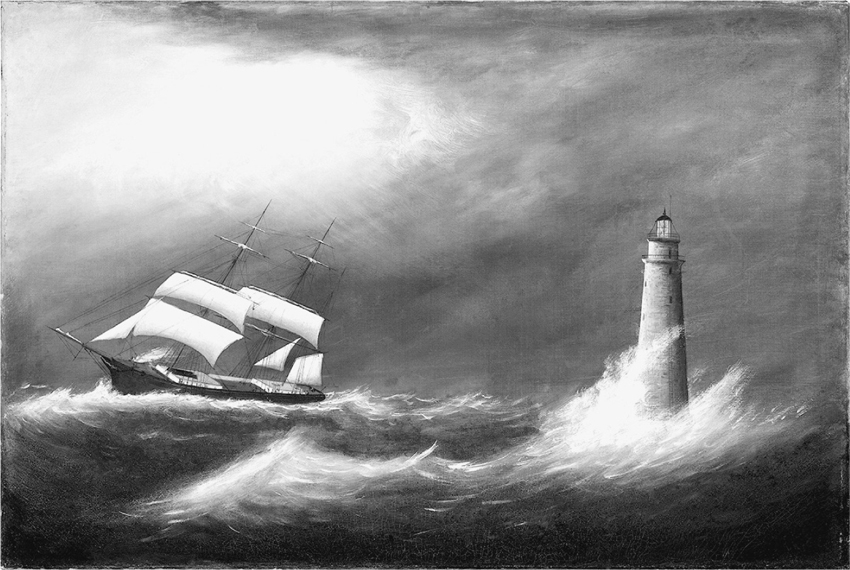

Clement Drew’s painting, titled Ship Passing Minot’s Light, circa 1860–80.

Long after the Civil War had run its bloody course, in 1894, the Lighthouse Board introduced a new system for identifying lighthouses, in which each lighthouse was given a distinctive numerical flash pattern. Minot’s was one of the first to be changed. That year a new second-order rotating Fresnel lens with multiple panels was installed in the lantern room, and instead of exhibiting a fixed white light, Minot’s now showed a 1–4–3 flash; that is, a single flash of light, followed by an interval of darkness, then four quick flashes, followed by another interval, then finally three more flashes. Not long after this new pattern went into effect, a romantically inclined observer saw in it something more than mere flashes: The 1-4-3 pattern corresponded numerically to the one of the most cherished phrases in the English language—“I Love You.” And from that point forward, Minot’s Lighthouse was known as the “I Love You Light.” Never mind that the staid government officials who made the switch certainly didn’t have amore on their minds.

Wave breaking on Minot’s Ledge.

A CONTINENT AWAY FROM Minot’s Ledge, in the Pacific Northwest, lies the Columbia River valley. The area had a booming economy in the 1870s, with commodities such as salmon, grain, timber, and gold fueling the region’s rapid growth. The main highway for commerce into and out of the valley was, of course, the Columbia River, which, at more than 1,200 miles long, was the longest river in the Pacific Northwest, and the fourth largest river in North America based on flow. Numerous ships had wrecked trying to negotiate the treacherous currents, towering waves, and hidden sandbars guarding the river’s mouth, a record of destruction that had contributed mightily to the sobriquet later given to this dangerous stretch of coast—the Graveyard of the Pacific. While the lighthouse established at Cape Disappointment in 1856, and another one built on nearby Point Adams in 1875, helped ships navigate the river’s mouth, commercial and shipping interests up and down the west coast were urging the government by the late 1870s to erect another lighthouse in the area to provide mariners an added measure of safety as they approached the river. Congress responded on June 20, 1878, ordering the board to build a beacon on Tillamook Head, a prominent headland twenty miles south of the Columbia.

However, the man tapped to investigate the proposed site, the army engineer G. L. Gillespie, believed that Congress had made a mistake. He argued that Tillamook Head, which rose well over one thousand feet above sea level, was a wrong if not outright dangerous place for a lighthouse. Not only was the headland too high, thereby ensuring that a lighthouse placed at or near the summit would often be shrouded in fog, but also just to get to the top of Tillamook Head would require building a road twenty miles through heavily wooded terrain, a daunting and very expensive prospect. As for building a lighthouse lower down on the face of Tillamook Head, Gillespie thought that was an equally impractical idea since the area was prone to frequent landslides.

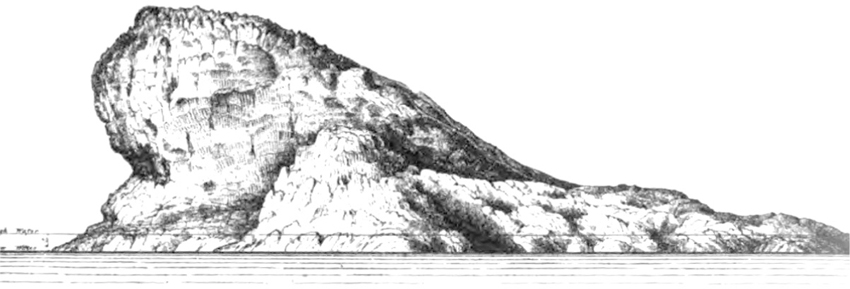

Rather than give up, Gillespie recommended an alternate site—Tillamook Rock. Located a little more than a mile off of Tillamook Head, the rock was a foreboding mass of basalt only an acre in size that jutted 120 feet out of the sea and was split into two unequal parts by a deep chasm. The surrounding waters ranged from 100 to 240 feet deep, and when the full fury of the Pacific was unleashed, tremendous waves battered the rock and often completely enveloped it in the incredible force of its violent embrace.

Gillespie’s proposal to place a lighthouse on the rock was met with ridicule and disbelief. As far as anyone knew, no one had ever set foot on the rock, not even the local Tillamook Indians, who thought it was cursed by the gods. And the logistics of landing work crews and building a lighthouse on such an exposed and wave-swept site, which was more than twenty miles from the nearest port at Astoria, Oregon,† seemed insurmountable, notwithstanding the board’s earlier success at Minot’s. Despite the logistical difficulties inherent in the project, the board trusted its engineer’s judgment and ordered him to devise a plan for conquering the fearsome rock. Gillespie, in turn, tasked the district superintendent of lighthouse construction, H. S. Wheeler, with the job.

On June 17, 1879, Gillespie sent Wheeler to Astoria, ordering him not to come back until he had landed on Tillamook Rock and taken measurements. Less than a week later the revenue cutter Thomas Corwin steamed to the rock with Wheeler and a few of his men on board. Although the seas were moderate, the waves breaking on the edge of Tillamook looked menacing as they clawed their way up the rock and fell back on themselves in a mass of seething white foam. The Corwin’s surfboat was gingerly maneuvered close to the rock at a spot where the seas were a bit calmer. Still, getting onto the rock was tricky. Since each passing swell caused the boat to rise and fall quickly, the men had to time their jumps perfectly or risk falling into the water. After a number of false starts, two of Wheeler’s men, crouching like tigers ready to pounce, leaped from the boat and landed successfully. Now all they needed were their surveying instruments, but before that transfer could be achieved, the seas became rougher, and the boat had to back off to avoid being smashed into the rocks. Panicked by the prospect of being marooned, the two men launched themselves into the water and were rescued by lifelines thrown from the boat.

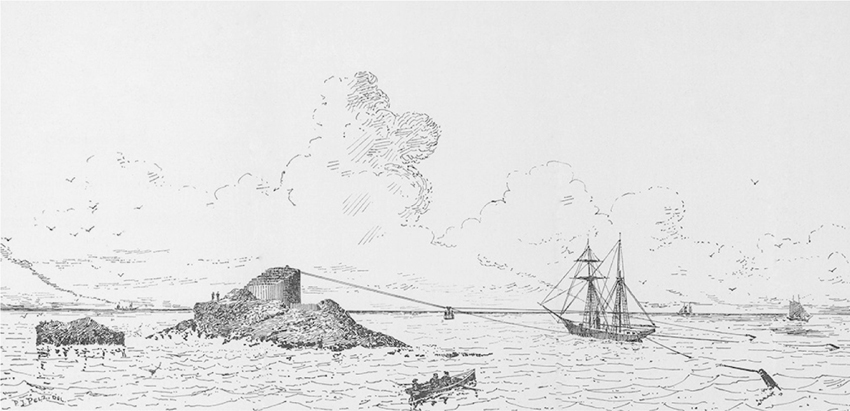

Wheeler returned to the rock four days later, and this time he made the leap but wasn’t able to land his instruments. Instead he used a hand tape to make rough measurements, which were enough for him to submit a general plan to the board. Determining where to situate the lighthouse was paramount, posing more than just a bit of a problem, since the crest of Tillamook Rock consisted of “a large rounded knob resembling the burl of a tree,” and was neither large nor flat enough to serve as an adequate base for the lighthouse. So Wheeler proposed having a work crew blast away the top thirty feet of the rock to create a flat platform about ninety feet above the water, upon which the lighthouse could sit. Once the platform was ready, construction of the lighthouse could begin, with all the building materials prepared on shore and ferried to the rock. The board approved the plan on September 11, 1879, and Congress consented to the changed location.

Profile of Tillamook Rock before the lighthouse was built.

To handle this monumentally tricky job, Wheeler appointed John R. Trewavas as superintendent of construction. Born in England, Trewavas had in the 1860s helped build the Wolf Rock Lighthouse, a hulking granite tower more than 115 feet high, located nine miles off Land’s End in Cornwall, England, on a wave-swept rock that measured roughly 130 by 100 feet. When Wheeler tapped Trewavas he was living in Portland, Oregon, and was considered one of the finest stonemasons on the West Coast. His first task was to thoroughly survey the rock, which he attempted to do on September 18. When the Corwin’s surfboat backed up to the rock, Trewavas steadied himself and then jumped. He made it to the rock but then slipped and fell, and was washed into the sea by a wave. A sailor dived in with a lifeline, but before he could effect a rescue, the gifted Englishman disappeared beneath the surface.

News of Trewavas’s death generated a strong backlash on the mainland. When the project was first announced, most area residents found the idea of building a lighthouse on Tillamook Rock foolhardy. Now that a death had occurred, many of them thought the undertaking so dangerous that it should be abandoned. If talk like this went on too long, the board feared it wouldn’t be able to hire local laborers because their minds would be poisoned against the project. To avoid this the board immediately appointed Alexander Ballantyne to replace Trewavas, and ordered him to hire a crew of quarrymen and head to Astoria right away, where a boat would be waiting to take him and his men directly to the rock.

Appointing Ballantyne, a heavily muscled bulldog of a man in his fifties, who was just below average height and sported a neat Vandyke beard, made good sense. Like Trewavas he hailed from Britain, but in his case from Scotland, and he had befriended Trewavas when they worked together at Wolf Rock. Soon after Trewavas headed to America, Ballantyne followed, and by the late 1870s the two of them had a thriving stonemason business operating out of Portland. Not only was Ballantyne an exceptionally talented mason, he was also a natural leader who inspired confidence and led by example.

Ballantyne soon had eight men under contract, but when he arrived in Astoria on September 23, the board’s plan for a quick getaway hit a snag. The fall gales had predictably descended on the coast, making the ocean conditions too rough for the Corwin to leave. Ballantyne had no way of knowing how long these conditions would last, and that worried him. If his men were stuck in Astoria for an extended period, he would not be able to keep them from frequenting local establishments where they would be exposed to the “idle talk of the town,” which might scare them off with lurid tales of Trewavas’s death and of the many dangers awaiting anyone who ventured to Tillamook Rock. Ballantyne couldn’t risk losing any of his men this way, so he moved them to the old keeper’s quarters at Cape Disappointment, which was across from Astoria on the Washington side of the river.

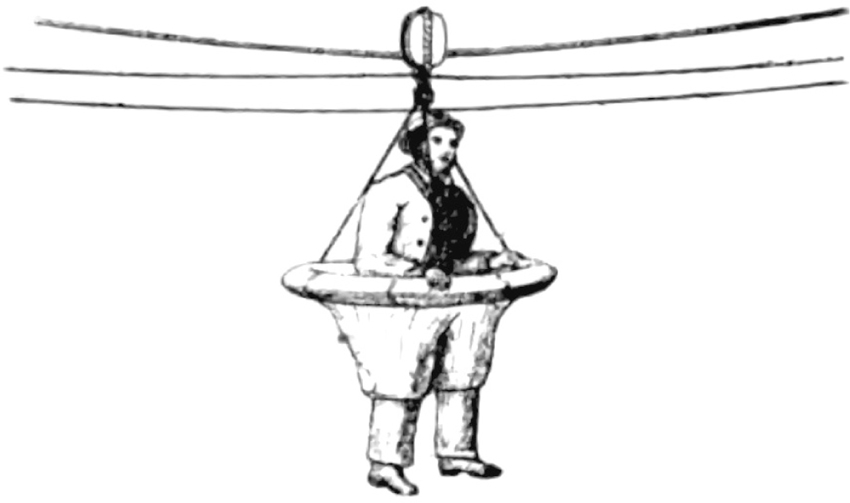

This isolation lasted until October 21, when the weather suddenly improved and the Corwin headed out. Ballantyne knew he had to devise a better method of getting men and materials onto the rock than jumping from a heaving surfboat, which had already claimed one life. His clever alternative was to create an aerial tramway of sorts. He ran a heavy rope from the mast of a moored ship to a point high on the rock, then rigged the rope with a traveler—a large block with a hook beneath it—that could be moved back and forth along the rope’s entire length by a continuous line attached to the shank of the traveler’s hook and looped around a pair of pulleys. Drawing the line in one direction brought the traveler to the ship, while drawing it in the other took it to Tillamook. Thus anything hung from the traveler’s hook could be transported on and off the rock.

To transport his men, Ballantyne employed a breeches buoy, which was simply a circular rubber life preserver attached to a pair of breeches (pants) cut off at the knees. The men slipped into the buoy, which was then suspended from the traveler’s hook, and off they went on what was invariably a wild and turbulent ride. Each passing wave rocked the boat, causing the rope to rise and fall quickly, alternately flinging the buoy’s passenger high into the air and then plunging him seaward. On any but extremely calm days, which were painfully rare, the rope’s gyrations were so great that the men were repeatedly dunked in the chilly water, and sometimes completely submerged for a few moments, arriving at their destination soaking wet, where the only thing that could help warm them up was the meager heat thrown off by the diminutive cookstove.

Most of the men braved the transit to the rock with good humor, or at least without much complaint, but there was one notable exception, a corpulent quarryman named Gruber who weighed three hundred pounds. He simply didn’t fit into the breeches buoy. Ballantyne proposed lashing the large man to the top of the buoy, a plan to which Gruber strenuously objected. The forceful Ballantyne would not give up, and he sent Gruber back to Astoria on the steamer and ordered him to be fitted out with a larger breeches buoy and return to the rock when it was ready.

Drawing of the breeches buoy and traveler used to transport workers onto and off Tillamook Rock.

When Gruber returned with the king-size buoy, however, he was overcome by paroxysms of fear and refused to get in. Hoping to allay Gruber’s concerns, Ballantyne climbed into the roomy buoy and told his men to haul away. Certainly, Ballantyne thought, once Gruber saw how safe and easy this was, he would acquiesce. But things didn’t work out as Ballantyne had hoped, and the “curse of the rock” asserted itself once again. The rope was so slack that Ballantyne was dragged through the water much of the way, only scaring Gruber more. Finally, after some not-so-gentle persuasion on Ballantyne’s part, Gruber reluctantly agreed to go across using a bosun’s chair—basically, a wooden plank supported by multiple ropes—while wearing a life preserver, since this mode of transportation gave him a little more freedom of movement than the buoy. To his great relief Gruber made it without even touching the water, becoming the first man to reach the rock completely dry.

The sea was not the only fear-inducing element, for the men were greeted by the bellowing of thousands of sea lions, which covered the rock like a writhing brown carpet and were not at all pleased by this invasion of their domain. Aggressive if approached, the sea lions at first stood their ground, forcing the men to be on their guard at all times while walking around the rock. Not long after the blasting began, however, the sea lions departed en masse for another haunt further to the south, as yet untrammeled by man.

The most immediate task the men faced upon landing was providing shelter for themselves and their supplies. Crude A-frame tents were fashioned from cut-up canvas and lashed with ropes to ringbolts inserted into the rock. It was “rather disagreeable” in the tent, according to Ballantyne, with the canvas flapping violently in the wind, and the rain and the sea spray drenching the men and their belongings. The tents, however, could be only temporary. With winter coming on, they needed something sturdier, and after leveling off an area about ninety feet above the water, they built a small wooden frame house to serve as their quarters.

While they were settling in, the blasting commenced. At first the men rappelled down the sides of the rock, suspended from ropes attached to ringbolts hammered into the summit. Some of the men sat in bosun’s chairs, while others tied the ropes loosely around their bodies. Dangling precariously nearly one hundred feet above the water, often buffeted by biting winds that caused them to sway ominously from side to side, the men drilled relatively shallow holes in the rock, plugged them with cartridges containing one pound of black powder, and then got out of the way before lighting the fuse. The explosions sent shards of rock into the air and plummeting into the water below. (No wonder, then, that the sea lions had wisely chosen to escape to a more serene location).

The goal of this work, soon achieved, was to create narrow benches upon which the men could stand so that they could increase the blasting intensity. The outer layer of the rock, which had been weathered and lashed by storms and waves for eons, was flaky and brittle, and as a result had been relatively easy to remove. But farther in the rock was denser and more difficult to dislodge. Now the men drilled larger and deeper holes that they filled with as much as one hundred pounds of black powder, generating increasingly powerful explosions that blew away up to 250 cubic yards of rock at a time.

As the men slowly blasted their way from the outer edges of the rock toward the center, weather remained their most persistent foe. Days of calm and good working conditions alternated with gale-force winds and pelting rains that made blasting difficult and at times impossible, not only threatening to blow the men off the rock but also soaking the powder so as to render it useless. Nothing, however, prepared them for the tempest that visited them in the New Year, as if to demarcate the 1880s with a most violent inauguration.

The storm began on January 2, 1880, and for the next four days the rain didn’t stop, the waves continued to mount, and the wind was so strong that the men could barely hold on to their tools. Nevertheless, they worked through the pain in their benumbed hands, and the increasing fatigue spreading through their bodies. On January 6, when the storm turned even more savage, Ballantyne halted work and told his men to batten down everything they could before retreating to their quarters.

That evening the storm morphed into a rare West Coast hurricane. By midnight heavy salt spray and fist-size chunks of rock were flying over the top of Tillamook. Ballantyne ordered his men to brace the roof and walls of their wooden house with drills and steel bars. Two hours later a tremendous sea rose out of the darkness, its swirling wind-driven whorls of spume mashing into the makeshift quarters, which barely withstood the assault. The blacksmith shop next to it, however, did not, and its roof was torn apart.

The men panicked, but Ballantyne, the resilient Scotsman, remained calm, and with his steely resolve he stopped them from fleeing the quarters to get to higher ground, a move that likely would have been their last, given the howling winds and the repeated blows from the sea. At four in the morning Ballantyne tentatively ventured outside, hoping to discover what had happened to the storehouse, located farther down the rock’s slope, a mere thirty-five feet above the water. Nearly blind in the inky darkness, he groped around for about half an hour, battered by the wind and waves, before returning to the quarters. With the coming of dawn he got his answer: The storehouse was destroyed, and everything in it was gone. Fortunately Ballantyne had stockpiled plenty of water and about three months’ worth of bread, bacon, beans, and tea in the quarters themselves, so he and his men were in no danger of starving.

For two more days the storm would not relent, the men remaining disagreeably cooped up, and when they finally emerged, continuing bad weather made it nearly impossible to work. In the meantime people on shore had become concerned about the men’s fate. Some of the materials washed from the rock during the storm had been found on nearby beaches, leading many to assume the worst. It wasn’t until January 18, almost two weeks later, that coastal waters were calm enough for relief ships to get to the rock with fresh provisions, and bring word back to the mainland that the men were in satisfactory shape.

From this point forward operations progressed smoothly, with only minor weather-related interruptions. Quarrymen were added to the work crew, and every week more of Tillamook Rock was blasted away. The most welcome change as far as the men were concerned was the erection of a steam-powered derrick fitted with a large boom, which eliminated the need to use the breeches buoy. Instead a cable lowered from the boom to the steamer’s deck and attached to a steel cage transported workers on and off the rock without getting them wet. The boom also made it much easier to land supplies.

Drawing of construction at Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, 1881.

By the end of May the platform for the lighthouse was complete. Roughly 4,700 cubic yards of rock had been removed, reducing the height of Tillamook from 120 to 91 feet. Ballantyne inspected the work, and, in his characteristically crisp fashion, pronounced it a job well done. Soon thereafter a much larger steam-powered derrick with an extremely long boom was secured to the rock and put to work lifting the heavy materials needed to build the lighthouse. The most important of these was the fine-grained basalt blocks quarried at Mount Tabor, a long-dormant volcanic cinder cone outside of Portland, which would form the structure’s shell.

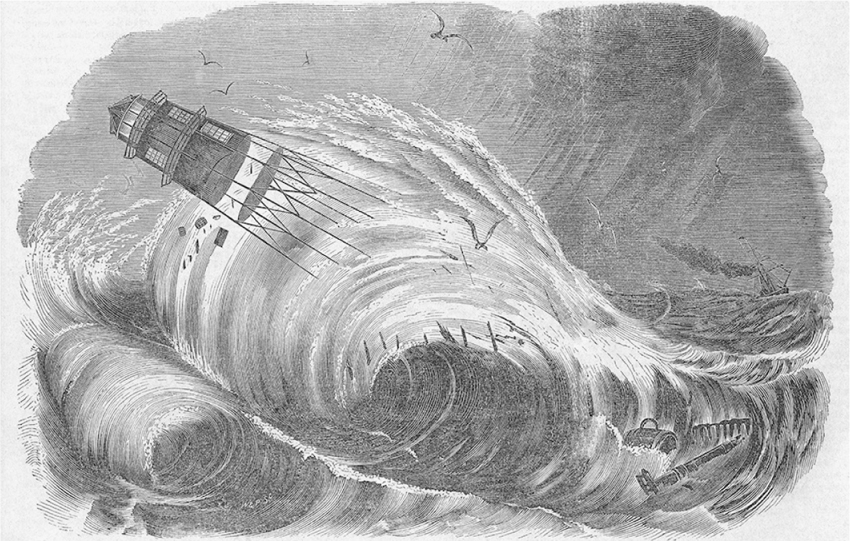

The lighthouse’s cornerstone was laid on June 22, and by the end of the year the building was nearly finished. On January 3, 1881, however, a disaster occurred that was a reminder of why a lighthouse on Tillamook was so desperately needed. The wind had been blowing hard all day, and visibility was extremely limited due to thick fog and driving rain. At eight that night, workers on Tillamook heard shouting in the distance, and soon after they emerged from their quarters they saw faint lights through the murk, followed immediately by the unmistakable command “Hard aport,” the order for turning a vessel sharply to the left. Wheeler, who was on Tillamook at the time, ordered the men to put out lanterns to warn the oncoming vessel away from the rock. The men could hear the ship’s masts and rigging creaking, and about two hundred yards off they saw the faint outlines of the ship before it disappeared into the night.

All they could do was hope that the ship had survived, but when the fog lifted in the morning, the tragic reality said otherwise. Near the base of the soaring cliffs of Tillamook Head, they could make out the ship’s masts peeking above the waves. As they would later learn, it was the British-flagged bark Lupatia, which had been heading from Japan to the Columbia River to pick up a cargo of wheat. Sixteen men were on board, but the sole survivor was the ship’s dog, an Australian shepherd, which was found whimpering on the rocks soon after the crash.

The accident weighed heavily on the minds of the Tillamook workers, who could not help but wonder if things might have turned out differently had the lighthouse been operational. One of them later remarked, “From that hour on, finishing the tower to get the light lit and the fog horn going was more than just a job.” Less than three weeks later, on January 21, the lighthouse cast its beam over the water for the first time.

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, 1891.

The lighthouse consisted of the keeper’s quarters and the fog-signal building, both one story high, connected to each other, and encased in two-foot-thick granite walls. The square tower, sixteen feet a side, was two stories high and rose out of the center of the dwelling. The lantern room sitting atop the tower housed a first-order Fresnel lens that displayed a white flash every five seconds. It had taken 575 days to build Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, at a cost of $123,493, and one brilliant life.

THE MISERABLE WEATHER AND dangerous conditions that plagued the Tillamook Lighthouse led mariners and its keepers to refer to it as Terrible Tilly. The storm that struck the lighthouse in October 1934 is just one of many, though arguably the worst, that helped forge this most fitting nickname. In the early morning hours of October 21, it slammed into the coast with wind gusts as high as 109 miles per hour. The unrelenting noise outside, however, would not deter assistant keeper Henry Jenkins from getting some well-deserved sleep after a long night tending to the light. But soon after dozing off around nine thirty in the morning, he awoke gasping for air. A wave breaking on the top of Tillamook had smashed open the storm shutters, flooding his room with the icy waters of the Pacific, washing him out of bed, and unceremoniously depositing him in a heap in the closet.

The lighthouse was under attack. Immense waves repeatedly engulfed the entire station, topping the lantern room that stood 133 feet above normal high tide. The sledgehammer-like walls of water ripped away a twenty-five-ton chunk of the rock, obliterated the station’s sizable derrick and severed the undersea telephone cable connecting Tillamook with the mainland.

The four keepers fought their way through swirling waters to the lantern room, where they were greeted with a scene of devastation. Flying debris and rocks—one weighing sixty pounds—had shattered sixteen of the lantern’s glass panels, and cracked or chipped many of the first-order Fresnel lens’s prisms. The oil vapor lamp was severely damaged and the lens’s revolving mechanism disabled. Glass shards, seaweed, and even small fish lay scattered about the room.

Working in water often up to their necks, the keepers struggled most of the day to clamp the lantern room’s storm shutters into place to protect against further aerial assaults. That night the lighthouse was dark, but by the next evening the men had rigged a small emergency lantern that sent forth a fixed white light. And Jenkins had cobbled together a shortwave radio set that enabled him to contact amateur radio operators on shore, who got word to the local superintendent of lighthouses about what was transpiring on the rock.

The storm raged until the twenty-fifth, and it was two more days before the seas calmed down enough for the tender Manzanita to arrive, providing relief and initiating repairs. Throughout their ordeal the keepers had no heat, little sleep, and they had to use a blowtorch to warm up their canned food. But every night with the exception of the first, they kept the emergency light burning. When the head of the Mexican lighthouse service read an article about this dramatic event in the Lighthouse Service Bulletin, he had it translated into Spanish and sent to all the keepers in his country “as an example of courageous performance of duty.”

SOON AFTER FINISHING THE Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, Ballantyne headed more than three hundred miles south to take on an even bigger challenge—the building of the St. George Reef Lighthouse. The reef is a chain of visible as well as submerged rocks located about six miles off Point St. George on the coast of Northern California, not far from the Oregon border. When the British naval officer and explorer George Vancouver encountered these rocks during his expedition to the Pacific Northwest in 1792, he said they were “very dangerous,” and christened them “Dragon Rocks.” And in fact the reef had long been a threat to shipping, but it wasn’t until an accident in 1865 that the idea of building a lighthouse in the area was first broached publicly.

During a gale on July 30, 1865, only months after the end of the Civil War, the Brother Jonathan, a 220-foot-long steam-powered sidewheeler, carrying 244 people and a shipment of gold, foundered on one of the rocks of St. George Reef. The ship sank within forty-five minutes, and all but nineteen of the people on board perished, making it the West Coast’s worst peacetime maritime disaster to date. The accident was widely covered by news outlets nationwide, and the desire to avoid future disasters spurred calls to build a lighthouse on the reef to warn of the danger.

The Lighthouse Board thought this an excellent idea, and within two years of the accident asked Congress to fund the project. Congress balked, in part because it was directing so much money to rebuilding what the Civil War had destroyed, including numerous eastern and southern lighthouses. Congress was also wary of placing a lighthouse on one of the reef’s wave-swept rocks. Despite the success at Minot’s Ledge, Congress was not convinced of the economic or engineering feasibility of building a lighthouse on a spot so fully exposed to the wrath of the often tempestuous Pacific.

Throughout the 1870s the board continued lobbying Congress to fund the lighthouse, to no avail. During this time the board considered two possible locations for the lighthouse—either on one of the reef’s rocks or on Point St. George, finally deciding against the latter, arguing that it would be too far away from the reef to serve as an effective warning. Instead the board concluded that the lighthouse should be built on Northwest Seal Rock, the part of St. George Reef farthest from the coast and closest to shipping lanes, and near where the Brother Jonathan had hurled its human cargo into a vengeful sea. The rock was roughly an acre in size, barely three hundred feet in diameter, and rose only fifty-four feet above the water.

The board approached Congress yet again in 1881, a propitious time because it was right after Ballantyne had conquered Tillamook, a project many had deemed impossible. If Tillamook could be tamed, Congress concluded, then so too could North West Seal Rock. As a result, in 1882, seventeen years after the Brother Jonathan disaster, Congress gave the board the go-ahead and the initial funding to begin building what would come to be known as the St. George Reef Lighthouse. The board, in turn, appointed Ballantyne to oversee construction.

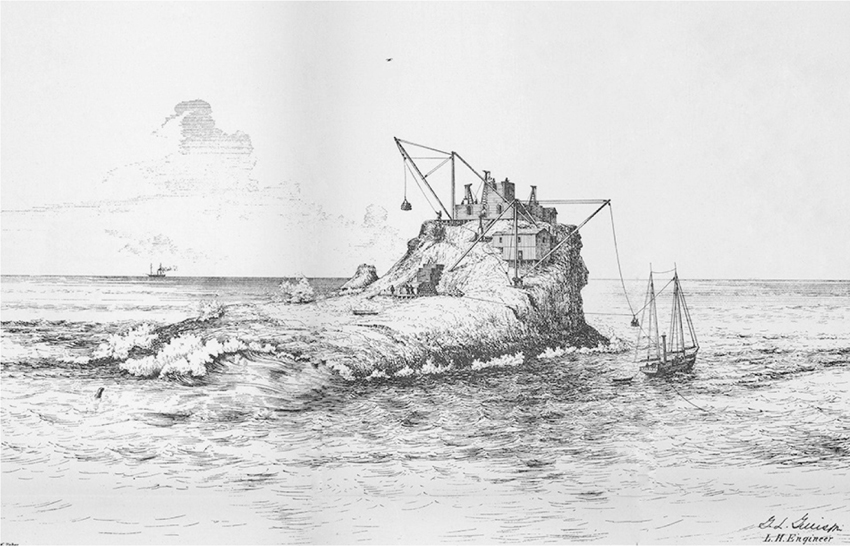

THE ST. GEORGE REEF LIGHTHOUSE would be quite different from the one at Tillamook. Instead of blasting off the top of the rock to make a platform for the lighthouse, the plan was to incorporate part of North West Seal Rock into the lighthouse’s foundation, thereby more securely anchoring the structure so that it could withstand the relentless hammering of ocean waves. A central column of rock would be blasted and chiseled down into a series of benches or terraces. Around and on this column an oval pier, or caisson, ninety feet in diameter and made of granite blocks would be built up to a height of nearly fifty feet. Much of the space between the outer caisson and the inner column of rock would be filled with rubble and concrete, but enough space would be left toward the top of the caisson to build a number of rooms, including the engine room, coal room, and storerooms. The top of the caisson would be covered with stone flagging, and the seven-story lighthouse would rise from there.

One of the first things the indefatigable Ballantyne had to decide was where to house his workers. The nearest port, Crescent City, was thirteen miles from North West Seal Rock. Lodging the men there would result in too much valuable time being lost in transport to and from the rock. Having the men stay on the rock was also not a viable option during the early stages of the project, when so much blasting would be going on in such a confined space. His answer was to moor a ship near the rock where his men would stay during the May-to-September work season.

A former sealing schooner, La Ninfa, was hired to serve as the workmen’s quarters. On April 3, 1883, the steamer Whitelaw took La Ninfa in tow and headed out from San Francisco to North West Seal Rock. The work party on La Ninfa numbered twenty-five, including the crew, quarrymen, stonecutters, and a blacksmith. Also on board were explosives, provisions, and tools. Stormy weather forced the Whitelaw to turn back twice before finally making it to the rock on April 9.

The immediate task was to moor La Ninfa about 350 feet away from the rock by securing it to four spar buoys that were in turn chained to mushroom sinkers—so named for their shape—that anchored the buoys in place. One sinker weighed six tons, while the other three were four tons. The Whitelaw was only able to lower the six-ton sinker and attach La Ninfa to its buoy before the seas got too rough, forcing the Whitelaw to steam off to wait out the storm. It wasn’t until a week later that the Whitelaw was able to return, but when the men tried to position the remaining moorings, they discovered that the water was far deeper than expected. As a result the spar buoys were not big or buoyant enough to stay much above the water, given the great weight of the extra chain hanging beneath them.

Ballantyne transferred all the men on La Ninfa to the Whitelaw, and then headed to Humboldt Bay, about seventy-five miles away, to procure larger buoys. The empty La Ninfa remained behind. Difficulties in obtaining the buoys and a stretch of nasty weather delayed the Whitelaw’s return to the rock until April 28. There was one major problem, though—La Ninfa was nowhere in sight, and neither was the buoy to which it had been attached.

A little more than a week later the missing schooner was found floating offshore not far from Crescent City. Ballantyne concluded that the same storm that had delayed his return to the rock with the new buoys had caused the eight-inch hawser that had been holding La Ninfa to its mooring to part, setting the ship adrift. The Whitelaw towed La Ninfa back to the rock, where the men secured it to four moorings; for additional stability it was also connected to the rock by two cables.

The men first set foot on the rock in early May, and over the next couple of days they landed drilling and stonecutting tools, blasting powder, and other supplies and provisions. These first landings were accomplished by rowing surfboats close in, whereupon the men jumped to the rock—a system that worked well as long the seas were relatively calm. But Ballantyne needed to be able to get his men on and off the rock even when conditions were rougher, and just as important, he needed a way to evacuate his men from the rock quickly when a storm blew in and waves threatened to wash over it, as they often did.

Ballantyne’s transport solution built upon what he had learned at Tillamook Rock. He ran a wire cable from La Ninfa’s masts to the top of North West Seal Rock, and then attached a traveler to the cable that was quite different from the one used at Tillamook. Instead of a block with a hook underneath, the traveler to North West Seal Rock was “made of two pieces of boiler plate, bolted together and forming the bearings for the axles of 4 grooved gun-metal wheels which just held the cable between the upper and lower pairs.” A four-foot-diameter horizontal iron ring with wooden planking affixed to it was suspended from this traveler, creating a cage in which four to six men could stand. The cage was moved to and from the rock by an endless line of cable attached to the traveler.

A donkey engine, or steam-powered winch, was soon employed, which propelled the men from the ship to the top of the rock. The engine’s services were not required on the return trip, because the steep descent from the top of the rock allowed the cage to travel down the cable at great speed, giving the men a thrilling ride, akin to today’s ziplining. While the men worked, Ballantyne kept an eye on the extremely mercurial weather. When waves started climbing up the sides of the rock, he would yell for the men to stop working, lash their tools to ringbolts embedded in the rock, and run for the cage. It took less than half an hour to evacuate all the men from the rock to the safety of the ship.

Severe storms delayed the work during that first season on the rock, but by July the summer weather moderated conditions, and blasting began in earnest. The process was similar to that used at Tillamook. Just before the fuses were lit the men would run for safety. As Ballantyne later recalled, “At my cry of ‘fire in the hole’ they would have to hunt for their holes like crabs.” But safety was only a relative concept, considering the shower of rock shrapnel the blasts sent flying in every direction, which bruised and bloodied many of the men. Some of the blasts were so powerful that they sent large chunks of rock raining down on La Ninfa more than three hundred feet away, leaving numerous scars on the ship’s exterior, but no major damage.

Drawing of construction proceeding on St. George Reef Lighthouse, showing the method of landing the men from La Ninfa.

In addition to dodging stone projectiles, the men had to contend with the persistently violent seas. Much of the time they were drenched in salt spray coming from waves breaking on the rock, and on September 10 two quarryman working near the top of the rock were hit by a huge wave that washed them thirty feet down the slope, where they landed on a flat surface, bruised but otherwise uninjured.

By the end of September 1883 the blasting had been completed, and the stage was set for building the masonry caisson. During the fall and spring of 1884, the project moved ahead on a number of fronts. Specifications detailed the exact size, shape, and ultimate location of all the stone blocks that would be used to build the caisson. Soon after these specifications were drawn up, a quarry along the Mad River, not far from Humboldt Bay, was contracted to provide the granite for the project. At the same time an extensive work area and depot were built on the north spit of Humboldt Bay, where stonecutters took the rough blocks and worked them into their final shapes. A wharf was also built at the spit to serve as a staging area for shipping the finished blocks to the rock.

Just when Ballantyne was looking forward to beginning work on the caisson, the project stalled. In three consecutive years—1884, 1885, and 1886—the board asked Congress for $150,000 to continue work on the lighthouse. But the United States, deep in the throes of a sustained depression, was economically ailing, and the situation was exacerbated by a panic that hit Wall Street in 1884, when a number of banks collapsed. With business failures on the rise and government revenues falling, Congress kept a tight rein on spending. As a result it appropriated only $30,000 for the lighthouse in 1884, $40,000 the next year, and nothing in 1886.

Since the board estimated that a single season of work on the rock cost at least $75,000, virtually all activity on the reef was halted during these three years. The modest funds that were available mostly went to keep the quarrymen and stonecutters on the mainland employed, but even their work in 1884 and 1885 was limited, while in 1886 it stopped altogether. This led Ballantyne to observe ruefully, “In four years only one working season of about one hundred days was utilized advantageously on the rock.”

With the economy rebounding, Congress appropriated $120,000 for the project in 1887, and work on the caisson commenced. Finished blocks, some weighing as much as six tons, were soon streaming to the rock by ship, where they were lifted in nets onto a pier by large boom derricks. Smaller derricks then helped the men maneuver the heavy stones into place. The blocks were numbered so that the men knew exactly where they should go. For added strength, each block was connected to its neighbor by a mortise-and-tenon joint, with the tenon (projection) being inserted into the mortise (cavity) to make a tight fit. To connect each course of blocks to the ones above and below, bronze dowels were inserted into precut holes. All the blocks were cemented together, with only three-sixteenths of an inch separating them. By the end of the 1887 season the caisson was twenty-two feet high.

The 1887 season, predictably, was not devoid of drama. A series of heavy gales added to the difficulty and danger of the work, as the men labored to move the huge blocks into their preassigned locations. Almost daily the men were forced to race to the cage to be taken off the rock to avoid being washed into the sea by gargantuan waves. The awesome power of these waves was on display during a storm in June when a 3.5-ton granite block that had been set into place thirty feet above the sea was lifted and thrown onto a higher bench cut into the reef, where it broke apart.

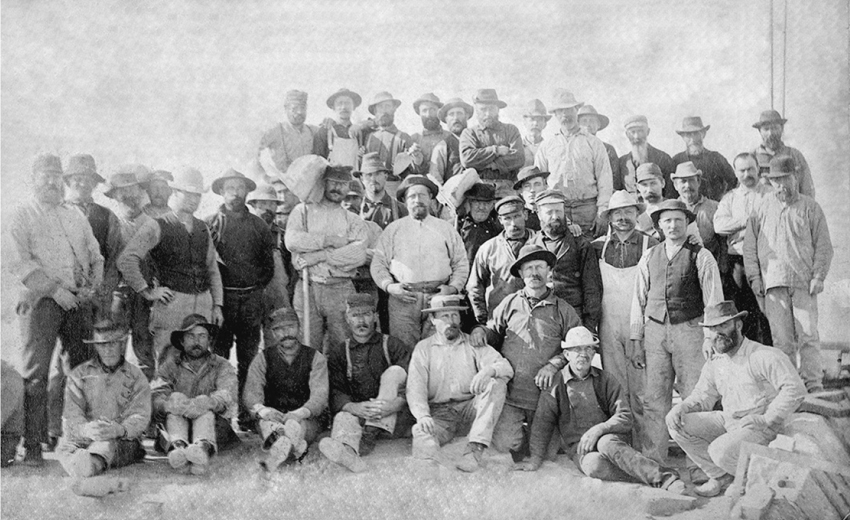

Workers who built the St. George Reef Lighthouse, circa 1888.

Over the next two years Congress provided a total of $350,000, enabling work to progress at a fast clip. Bigger derricks were employed, a larger pier was built on the rock for offloading materials, and in 1888 Ballantyne had his men build permanent quarters on the rock, which had room for the fifty-two men who were now laboring on the project. The men had already been sleeping high up on the rock in temporary structures, but when conditions became rough they still had to use the cage to rush back to the ship moored offshore. The permanent quarters eliminated the need for the cage and the ship, and allowed the men to increase their efficiency by spending more time working; and in bad weather they could get to safety much faster. But in reality no place on the rock could truly be considered safe at this time, especially when the Pacific became cantankerous. In May 1889, a ferocious storm hit the rock, with waves pounding the workmen’s quarters, causing its two-foot thick wooden beams to pulsate. One particularly nasty breaker crashed open the doors, and filled the building with a swirling maelstrom of salt water, which sucked a few of the men right outside, leaving them clinging to the rocks lest they be swept into the sea. Ballantyne, ever the unflappable Scot, tersely recorded the event in his journal, noting, “The men’s quarters, although strongly built, were smashed in during a gale about 2 o’clock one morning in May. No one was injured, but some of the men were washed out of their bunks.”

By 1889 the caisson, comprising 1,339 granite blocks, was essentially complete, with only a minor amount of paving yet to be done at the top. Due to a delay in funding in 1890, work on the lighthouse tower didn’t begin until 1891. The first stone of the square tower was laid on May 13, and the last was lowered into place on August 23. The only fatality of the entire project occurred during this time, when a workman holding a rope attached to a cargo net moving overhead failed to let go of the rope in time and was dragged over the edge of the caisson, falling to his death on the rocks below. Given the extreme weather, the crashing waves, the blasting, the precipitous flights on the aerial tramway, and the huge number of unwieldy granite blocks that had to be raised, moved, and lowered into place, it is a testament to late-nineteenth-century American engineering, as well as Ballantyne’s oversight and his men’s skill, that only one person died during the project.

At last, on October 29, the men, having topped the tower with its iron lantern room and put the finishing touches on the lighthouse, were done. It was an engineering feat worthy of a mythological fable. But just when the workers were ready to leave, St. George Reef, as if in a scene scripted by Homer, would not let them go. For more than a week a tremendous storm, producing thunderous waves that caused the caisson and tower to shudder, imprisoned the men in their own creation. On November 8, after the storm ended and the waves died down, the relieved workmen finally departed the rock, more confident than ever that the lighthouse could withstand whatever the unruly Pacific had to offer.

On December 1, 1891, the station’s fog whistles began sounding, but it would be almost another year before the custom-made first-order Fresnel lens arrived from France and was installed in the tower. When the lighthouse began shining on October 20, 1892, its intense light streamed from the lantern room at 146 feet above the water and could be seen up to twenty miles away.

St. George Reef Lighthouse, circa 1963.

The entire endeavor had taken roughly a decade from start to finish, and had cost $752,000, making St. George Reef far and away the most expensive lighthouse ever built in the United States. To put that in perspective, consider that the Statue of Liberty, which was finished in 1886, is estimated to have cost around $600,000 to build, pedestal and all.

* Government Island is now connected to the mainland.

† Astoria was named after the fur merchant John Jacob Astor, and America’s first multimillionaire, who unsuccessfully attempted to create a fur-trading empire on the banks of the Columbia River.