CHAPTER VI : SHIVA

The Supremacy of Shiva

THIS story is related by Brahm in answer to an inquiry of the gods and rishis: “ In the night of Brahm

in answer to an inquiry of the gods and rishis: “ In the night of Brahm , when all beings and all worlds are resolved together in one equal and inseparable stillness, I beheld the great N

, when all beings and all worlds are resolved together in one equal and inseparable stillness, I beheld the great N r

r yana, soul of the universe, thousand-eyed, omniscient, Being and non-Being alike, reclining on the formless waters, supported by the thousand-headed serpent Infinite; and I, deluded by his glamour, touched the eternal being with my hand and asked: ‘Who art thou ? Speak.’ Then he of the lotus-eyes looked upon me with drowsy glance, then rose and smiled, and said : ‘ Welcome, my child, thou shining grandsire.’ But I took offence thereat and said : ‘Dost thou, O sinless god, like a teacher to a pupil, call me child, who am the cause of creation and destruction, framer of the myriad worlds, the source and soul of all ? Tell me why dost thou thus speak foolish words to me?’ Then Vishnu answered: ‘Knowest thou not that I am N

yana, soul of the universe, thousand-eyed, omniscient, Being and non-Being alike, reclining on the formless waters, supported by the thousand-headed serpent Infinite; and I, deluded by his glamour, touched the eternal being with my hand and asked: ‘Who art thou ? Speak.’ Then he of the lotus-eyes looked upon me with drowsy glance, then rose and smiled, and said : ‘ Welcome, my child, thou shining grandsire.’ But I took offence thereat and said : ‘Dost thou, O sinless god, like a teacher to a pupil, call me child, who am the cause of creation and destruction, framer of the myriad worlds, the source and soul of all ? Tell me why dost thou thus speak foolish words to me?’ Then Vishnu answered: ‘Knowest thou not that I am N r

r yana, creator, preserver, and destroyer of the worlds, the eternal male, the undying source and centre of the universe ? For thou wert born from my own imperishable body.’

yana, creator, preserver, and destroyer of the worlds, the eternal male, the undying source and centre of the universe ? For thou wert born from my own imperishable body.’

“ Now ensued an angry argument between us twain upon that formless sea. Then for the ending of our contention there appeared before us a glorious shining lingam, a fiery pillar, like a hundred universe-consuming fires, without beginning, middle, or end, incomparable, indescribable. The divine Vishnu, bewildered by its thousand flames, said unto me, who was as much astonished as himself : ‘Let us forthwith seek to know this fire’s source. I will descend ; do thou ascend with all thy power.’ Then he became a boar, like a mountain of blue collyrium, a thousand leagues in width, with white sharp-pointed tusks, long-snouted, loud-grunting, short of foot, victorious, strong, incomparable—and plunged below. For a thousand years he sped thus downward, but found no base at all of the lingam. Meanwhile I became a swan, white and fiery-eyed, with wings on every side, swift as thought and as the wind; and I went upward for a thousand years, seeking to find the pillar’s end, but found it not. Then I returned and met the great Vishnu, weary and astonished, on his upward way.

“ Then Shiva stood before us, and we whom his magic had guiled bowed unto him, while there arose about on every hand the articulate sound of ‘ Om,’ clear and lasting. To him N r

r yana said : ‘Happy has been our strife, thou God of gods, forasmuch as thou hast appeared to end it.’ Then Shiva answered to Vishnu: ‘Thou art indeed the creator, preserver, and destroyer of the worlds; do thou, my child, maintain this world both moving and inert. For I, the undivided Overlord, am three, am Brahm

yana said : ‘Happy has been our strife, thou God of gods, forasmuch as thou hast appeared to end it.’ Then Shiva answered to Vishnu: ‘Thou art indeed the creator, preserver, and destroyer of the worlds; do thou, my child, maintain this world both moving and inert. For I, the undivided Overlord, am three, am Brahm , Vishnu, and Rudra, who create, maintain, destroy. Cherish this Brahm

, Vishnu, and Rudra, who create, maintain, destroy. Cherish this Brahm , for he shall be born of thee in an ensuing age. Then shall ye twain behold myself again.’ Therewith the Great God vanished. Thereafter has the worship of the lingam been established in the three worlds.”

, for he shall be born of thee in an ensuing age. Then shall ye twain behold myself again.’ Therewith the Great God vanished. Thereafter has the worship of the lingam been established in the three worlds.”

Sat

Very long ago there was a chief of the gods named Daksha. He married Prasuti, daughter of Manu ; she bore him sixteen daughters, of whom the youngest, Sat , became the wife of Shiva. This was a match unpleasing to her father, for he had a grudge against Shiva, not only for his disreputable habits, but because Shiva, upon the occasion of a festival to which he had been invited, did not offer homage to Daksha. For this reason Daksha had pronounced a curse upon Shiva, that he should receive no portion of the offerings made to the gods. A Brahman of Shiva’s party, however, pronounced the contrary curse, that Daksha should waste his life in material pleasures and ceremonial observances and should have a face like a goat.

, became the wife of Shiva. This was a match unpleasing to her father, for he had a grudge against Shiva, not only for his disreputable habits, but because Shiva, upon the occasion of a festival to which he had been invited, did not offer homage to Daksha. For this reason Daksha had pronounced a curse upon Shiva, that he should receive no portion of the offerings made to the gods. A Brahman of Shiva’s party, however, pronounced the contrary curse, that Daksha should waste his life in material pleasures and ceremonial observances and should have a face like a goat.

Meanwhile Sat grew up and set her heart on Shiva, worshipping him in secret. She became of marriageable age, and her father held a swayamvara, or own-choice, for her, to which he invited gods and princes from far and near, except only Shiva. Then Sat

grew up and set her heart on Shiva, worshipping him in secret. She became of marriageable age, and her father held a swayamvara, or own-choice, for her, to which he invited gods and princes from far and near, except only Shiva. Then Sat was borne into the great assembly, wreath in hand. But Shiva was nowhere to be seen, amongst gods or men. Then in despair she cast her wreath into the air, calling upon Shiva to receive the garland ; and behold he stood in the midst of the court with the wreath about his neck. Daksha had then no choice but to complete the marriage; and Shiva went away with Sat

was borne into the great assembly, wreath in hand. But Shiva was nowhere to be seen, amongst gods or men. Then in despair she cast her wreath into the air, calling upon Shiva to receive the garland ; and behold he stood in the midst of the court with the wreath about his neck. Daksha had then no choice but to complete the marriage; and Shiva went away with Sat to his home in Kail

to his home in Kail s.

s.

This Kail s was far away beyond the white Himalayas, and there Shiva dwelt in royal state, worshipped by gods and rishis ; but more often he spent his time wandering about the hill like a beggar, his body smeared with ashes, and with Sat

s was far away beyond the white Himalayas, and there Shiva dwelt in royal state, worshipped by gods and rishis ; but more often he spent his time wandering about the hill like a beggar, his body smeared with ashes, and with Sat wearing ragged robes ; sometimes also he was seen in the cremation grounds, surrounded by dancing imps and taking part in horrid rites.

wearing ragged robes ; sometimes also he was seen in the cremation grounds, surrounded by dancing imps and taking part in horrid rites.

One day Daksha made arrangements for a great horse sacrifice, and invited all the gods to come and share in the offerings, omitting only Shiva. The chief offerings were to be made to Vishnu. Presently Sat observed the departure of the gods, as they set out to visit Daksha, and turning to her lord, she asked : “ Whither, O lord, are bound the gods, with Indra at their head ? for I wonder what is toward.” Then Mah

observed the departure of the gods, as they set out to visit Daksha, and turning to her lord, she asked : “ Whither, O lord, are bound the gods, with Indra at their head ? for I wonder what is toward.” Then Mah deva answered: “ Shining lady, the good patriarch Daksha has prepared a horse sacrifice, and thither the gods repair.” She asked him : “Why dost thou not also go to this great ceremony ? He answered: ” It has been contrived amongst the gods that I should have no part in any such offerings as are made at sacrifices.” Then Devi was angry and she exclaimed : ” How can it be that he who dwells in every being, he who is unapproachable in power and glory, should be excluded from oblations ? What penance, what gift shall I make that my lord, who transcends all thought, should receive a share, a third or a half, of the oblation? ” Then Shiva smiled at Devi, pleased with her affection; but he said : ”These offerings are of little moment to me, for they sacrifice to me who chant the hymns of the S

deva answered: “ Shining lady, the good patriarch Daksha has prepared a horse sacrifice, and thither the gods repair.” She asked him : “Why dost thou not also go to this great ceremony ? He answered: ” It has been contrived amongst the gods that I should have no part in any such offerings as are made at sacrifices.” Then Devi was angry and she exclaimed : ” How can it be that he who dwells in every being, he who is unapproachable in power and glory, should be excluded from oblations ? What penance, what gift shall I make that my lord, who transcends all thought, should receive a share, a third or a half, of the oblation? ” Then Shiva smiled at Devi, pleased with her affection; but he said : ”These offerings are of little moment to me, for they sacrifice to me who chant the hymns of the S maveda ; my priests are those who offer the oblation of true wisdom, where no officiating Brahman is needed ; that is my portion.” Devi answered : ” It is not difficult to make excuses before women. Howbeit, thou shouldst permit me at least to go to my father’s house on this occasion.” ” Without invitation ? ”he asked. ” A daughter needs no invitation to her father’s house,” she replied. “So be it,” answered Mah

maveda ; my priests are those who offer the oblation of true wisdom, where no officiating Brahman is needed ; that is my portion.” Devi answered : ” It is not difficult to make excuses before women. Howbeit, thou shouldst permit me at least to go to my father’s house on this occasion.” ” Without invitation ? ”he asked. ” A daughter needs no invitation to her father’s house,” she replied. “So be it,” answered Mah deva, “ but know that ill will come of it; for Daksha will insult me in your presence.”

deva, “ but know that ill will come of it; for Daksha will insult me in your presence.”

So Devi went to her father’s house, and there she was indeed received, but without honour, for she rode on Shiva’s bull and wore a beggar’s dress. She protested against her father’s neglect of Shiva; but Daksha broke into angry curses and derided the “ king of goblins,” the “ beggar,” the “ash-man,” the long-haired yogi. Sat answered her father: “Shiva is the friend of all; no one but you speaks ill of him. All that thou sayest the devas know, and yet adore him. But a wife, when her lord is reviled, if she cannot slay the evil speakers, must leave the place, closing her ears with her hands, or, if she have power, should surrender her life. This I shall do, for I am ashamed to own this body to such as thee.” Then Sat

answered her father: “Shiva is the friend of all; no one but you speaks ill of him. All that thou sayest the devas know, and yet adore him. But a wife, when her lord is reviled, if she cannot slay the evil speakers, must leave the place, closing her ears with her hands, or, if she have power, should surrender her life. This I shall do, for I am ashamed to own this body to such as thee.” Then Sat released the inward consuming fire and fell dead at Daksha’s feet.

released the inward consuming fire and fell dead at Daksha’s feet.

The Anger of Shiva

N rada bore the news to Shiva. He burned with anger, and tore from his head a lock of hair, glowing with energy, and cast it upon the earth. The terrible demon Virabhadra sprang from it; his tall body reached the high heavens, he was dark as the clouds, he had a thousand arms, three burning eyes, and fiery hair; he wore a garland of skulls and carried terrible weapons. This demon bowed at Shiva’s feet and asked his will. He answered: “Lead my army against Daksha and destroy his sacrifice ; fear not the Brahmans, for thou art a portion of my very self.” Then this dread sending appeared with Shiva’s ganas in the midst of Daksha’s assembly like a storm of wind. They broke the sacrificial vessels, polluted the offerings, and insulted the priests; finally V

rada bore the news to Shiva. He burned with anger, and tore from his head a lock of hair, glowing with energy, and cast it upon the earth. The terrible demon Virabhadra sprang from it; his tall body reached the high heavens, he was dark as the clouds, he had a thousand arms, three burning eyes, and fiery hair; he wore a garland of skulls and carried terrible weapons. This demon bowed at Shiva’s feet and asked his will. He answered: “Lead my army against Daksha and destroy his sacrifice ; fear not the Brahmans, for thou art a portion of my very self.” Then this dread sending appeared with Shiva’s ganas in the midst of Daksha’s assembly like a storm of wind. They broke the sacrificial vessels, polluted the offerings, and insulted the priests; finally V rabhadra cut off Daksha’s head, trampled on Indra, broke the staff of Yama, and scattered the gods on every side; then he returned to Kail

rabhadra cut off Daksha’s head, trampled on Indra, broke the staff of Yama, and scattered the gods on every side; then he returned to Kail s. There Shiva sat unmoved, plunged in the deepest thought, forgetful of what had passed. The defeated gods sought Brahm

s. There Shiva sat unmoved, plunged in the deepest thought, forgetful of what had passed. The defeated gods sought Brahm and asked his counsel. He, with Vishnu, had abstained from attending the festival, for they had foreseen what would befall. Now Brahma advised the gods to make their peace with Shiva, who could destroy the universe at his will. Brahm

and asked his counsel. He, with Vishnu, had abstained from attending the festival, for they had foreseen what would befall. Now Brahma advised the gods to make their peace with Shiva, who could destroy the universe at his will. Brahm himself went with them to Kail

himself went with them to Kail s. They found Shiva plunged in deep meditation in the garden of the kinnaras called Fragrant, under a great pipal-tree a hundred leagues in height, its branches spreading forty leagues on either side. Brahm

s. They found Shiva plunged in deep meditation in the garden of the kinnaras called Fragrant, under a great pipal-tree a hundred leagues in height, its branches spreading forty leagues on either side. Brahm prayed him to pardon Daksha and to mend the broken limbs of gods and rishis, “for,” he said, “the offerings are thine; receive them and permit the sacrifice to be completed.” Then Shiva answered : “ Daksha is but a child; I do not think of him as one who has committed sin. His head, however, has been burnt; I shall bestow on him a goat’s head, and the broken limbs shall be made whole.” Then the devas thanked Shiva for his gentleness, and invited him to the sacrifice. There Daksha looked on him with reverence, the rite was duly performed, and there also Vishnu appeared riding upon Garuda. He spoke to Daksha, saying : “ Only the unlearned deem myself and Shiva to be distinct; he, I, and Brahm

prayed him to pardon Daksha and to mend the broken limbs of gods and rishis, “for,” he said, “the offerings are thine; receive them and permit the sacrifice to be completed.” Then Shiva answered : “ Daksha is but a child; I do not think of him as one who has committed sin. His head, however, has been burnt; I shall bestow on him a goat’s head, and the broken limbs shall be made whole.” Then the devas thanked Shiva for his gentleness, and invited him to the sacrifice. There Daksha looked on him with reverence, the rite was duly performed, and there also Vishnu appeared riding upon Garuda. He spoke to Daksha, saying : “ Only the unlearned deem myself and Shiva to be distinct; he, I, and Brahm are one, assuming different names for the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe. We, as the triune Self, pervade all creatures; the wise therefore regard all others as themselves.”

are one, assuming different names for the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe. We, as the triune Self, pervade all creatures; the wise therefore regard all others as themselves.”

Then all the gods and rishis saluted Shiva and Vishnu and Brahm , and departed to their places; but Shiva returned to Kail

, and departed to their places; but Shiva returned to Kail s and fell once more into his dream.

s and fell once more into his dream.

Note on Daksha and Shiva

It happens constantly in the history of Indian literature that a new wave of theology becomes the occasion for a recapitulation of an older theory of the origin of the universe. This fact is the good fortune of later students, for without it we should have had no clue whatever in a majority of cases to the ancient conceptions. Of such an order, we may take it, is the story of Daksha. It was held by the promulgators of Aryan and Sanskritic views that Brahm had, vaguely speaking, been the creator of the worlds. But amongst those to whom he was sacred there grew up, we must remember, the philosophy of the inherent evil and duality of material existence. And with the perfecting of this theory the name of a new god, Shiva or Mah

had, vaguely speaking, been the creator of the worlds. But amongst those to whom he was sacred there grew up, we must remember, the philosophy of the inherent evil and duality of material existence. And with the perfecting of this theory the name of a new god, Shiva or Mah deva, embodying spiritual enlightenment, became popular. Now what part could have been played, in the evolution of the cosmos, by these different divinities? This was a world in which good brought forth evil, and evil brought forth good, and good without evil was a mere contradiction in terms. How, then, could the Great God be made responsible for anything so disastrous? Plainly, he could not. So the myth was elaborated that Brahm

deva, embodying spiritual enlightenment, became popular. Now what part could have been played, in the evolution of the cosmos, by these different divinities? This was a world in which good brought forth evil, and evil brought forth good, and good without evil was a mere contradiction in terms. How, then, could the Great God be made responsible for anything so disastrous? Plainly, he could not. So the myth was elaborated that Brahm had at first created four beautiful youths to be the progenitors of mankind, and they had sat down to worship on the banks of Lake M

had at first created four beautiful youths to be the progenitors of mankind, and they had sat down to worship on the banks of Lake M nasarovara. Suddenly there came to them Shiva in the form of a great swan—the prototype of the Paramahamsa, or supreme swan, the title of the emancipated soul—who swam hither and thither, warning them that the world about them was an illusion and a bondage, and that their one way of escape lay in refusing to become fathers. The young men heard and understood, and, plunging into meditation, they remained on the shores of the divine lake, useless for any of the purposes of the world. Then Brahm

nasarovara. Suddenly there came to them Shiva in the form of a great swan—the prototype of the Paramahamsa, or supreme swan, the title of the emancipated soul—who swam hither and thither, warning them that the world about them was an illusion and a bondage, and that their one way of escape lay in refusing to become fathers. The young men heard and understood, and, plunging into meditation, they remained on the shores of the divine lake, useless for any of the purposes of the world. Then Brahm created the eight lords of creation, the Praj

created the eight lords of creation, the Praj patis, and they it was who made up the muddle that is called this world.

patis, and they it was who made up the muddle that is called this world.

The history of ideas is perhaps the only history that can be clearly followed out in India, but this is traceable with a wonderful distinctness. At this point in the history of Brahm , where he creates the Praj

, where he creates the Praj patis, in a story whose evident object it is to show the part played by Shiva in the process of creation, it is obvious that we are suddenly taking on board the whole of a more ancient cosmogony. The converse fact, that the gods of that mythology are meeting for the first time with a new series of more ethical and spiritual conceptions than have hitherto been familiar to them, is equally indisputable as the story proceeds. One of the new Praj

patis, in a story whose evident object it is to show the part played by Shiva in the process of creation, it is obvious that we are suddenly taking on board the whole of a more ancient cosmogony. The converse fact, that the gods of that mythology are meeting for the first time with a new series of more ethical and spiritual conceptions than have hitherto been familiar to them, is equally indisputable as the story proceeds. One of the new Praj patis has an established conviction—incongruous enough in a new creation, but not unnatural in a case of great seniority—that he himself is Overlord of men and gods, and it is greatly to his chagrin and disgust that he finds his rank and pretensions ignored by that god who is known as Shiva or Mah

patis has an established conviction—incongruous enough in a new creation, but not unnatural in a case of great seniority—that he himself is Overlord of men and gods, and it is greatly to his chagrin and disgust that he finds his rank and pretensions ignored by that god who is known as Shiva or Mah deva. In this very fact of the suddenness of the offence given, and the unexpectedness of the slight, we have an added indication that we are here dealing with the introduction of a new god into the Hindu pantheon. He is to be made a member of its family circle by a device that is at once old and eternally new. The chief Praj

deva. In this very fact of the suddenness of the offence given, and the unexpectedness of the slight, we have an added indication that we are here dealing with the introduction of a new god into the Hindu pantheon. He is to be made a member of its family circle by a device that is at once old and eternally new. The chief Praj pati—Daksha by name—out of wounded pride, conceives a violent feud against Shiva, the Great God. But Daksha had a daughter called Sat

pati—Daksha by name—out of wounded pride, conceives a violent feud against Shiva, the Great God. But Daksha had a daughter called Sat , who is the very incarnation of womanly piety and devotion. This maiden’s whole soul is given up in secret to the worship and love of the Great God. Now she is the last unmarried daughter of her father, and the time for her wooing and betrothal cannot be much longer delayed. It is announced, therefore, that her Swayamvara—the ceremony of choosing her own husband performed by a king’s daughter—is about to be held, and invitations are issued to all the eligible gods and princes. Shiva alone is not invited, and to Shiva the whole heart of Sat

, who is the very incarnation of womanly piety and devotion. This maiden’s whole soul is given up in secret to the worship and love of the Great God. Now she is the last unmarried daughter of her father, and the time for her wooing and betrothal cannot be much longer delayed. It is announced, therefore, that her Swayamvara—the ceremony of choosing her own husband performed by a king’s daughter—is about to be held, and invitations are issued to all the eligible gods and princes. Shiva alone is not invited, and to Shiva the whole heart of Sat is irrevocably given. On stepping into the pavilion of the bridal choice, therefore, with the marriage garland in her hand, Sat

is irrevocably given. On stepping into the pavilion of the bridal choice, therefore, with the marriage garland in her hand, Sat makes a supreme appeal. “ If I be indeed Sat

makes a supreme appeal. “ If I be indeed Sat ,” she exclaims, throwing the garland into the air, “ then do thou, Shiva, receive my garland!” And immediately he was there in the midst of them with her garland round his neck. The story of the further development of the feud is related above. Ancient as is now the story of the wedding of the daughter of the older Lord of Creation with the new-comer amongst the gods, it is clear at this point that Daksha was already so old that the origin of his goat’s head had been forgotten, and was felt to require explanation by the world of the day that accepted Shiva. To an age before the birth of Buddhism he may have been familiar enough, but the preaching of that faith throughout the length and breadth of India must by this time have educated the people to demanding moral and spiritual attributes in their deities instead of a mere congeries of cosmic powers, and so trained they came back, it would appear, to the conception of Daksha as to something whose significance they had forgotten.

,” she exclaims, throwing the garland into the air, “ then do thou, Shiva, receive my garland!” And immediately he was there in the midst of them with her garland round his neck. The story of the further development of the feud is related above. Ancient as is now the story of the wedding of the daughter of the older Lord of Creation with the new-comer amongst the gods, it is clear at this point that Daksha was already so old that the origin of his goat’s head had been forgotten, and was felt to require explanation by the world of the day that accepted Shiva. To an age before the birth of Buddhism he may have been familiar enough, but the preaching of that faith throughout the length and breadth of India must by this time have educated the people to demanding moral and spiritual attributes in their deities instead of a mere congeries of cosmic powers, and so trained they came back, it would appear, to the conception of Daksha as to something whose significance they had forgotten.

Suggestions of Earlier Myths

Traces of something still more ancient are to be seen in the next act of this sacred drama, when Shiva, drunk with sorrow, strides about the earth, all destroying, bearing the form of the dead Sat on his back. The soil is dried up, plants wither, harvests fail. All nature shudders under the grief of the Great God. Then Vishnu, to save mankind, comes up behind Shiva and, hurling his discus time after time, cuts the body of Sat

on his back. The soil is dried up, plants wither, harvests fail. All nature shudders under the grief of the Great God. Then Vishnu, to save mankind, comes up behind Shiva and, hurling his discus time after time, cuts the body of Sat to pieces till the Great God, conscious that the weight is gone, retires alone to Kail

to pieces till the Great God, conscious that the weight is gone, retires alone to Kail s to lose himself once more in his eternal meditation. But the body of Sat

s to lose himself once more in his eternal meditation. But the body of Sat has been hewn into fifty-two dieces, and wherever a fragment touches earth a shrine of mother-worship is established, and Shiva himself shines forth before the suppliant as the guardian of that spot.

has been hewn into fifty-two dieces, and wherever a fragment touches earth a shrine of mother-worship is established, and Shiva himself shines forth before the suppliant as the guardian of that spot.

This whole story brings vividly back to us the quest of Persephone by Demeter, the Great Goddess, that beautiful Greek myth of the northern winter; but in the fifty-two pieces of the body of Sat we are irresistibly reminded of the seventy-two fragments of another dead body, that of Osiris, which was sought by Isis and found in the cypress-tree at Byblos. The oldest year is said to have been one of two seasons, or seventy-two weeks. Thus the body of Osiris would perhaps signify the whole year, divided into its most calculable units. In the more modern story we find ourselves dealing again with a number characteristic of the weeks of the year. The fragments of the body of Sat

we are irresistibly reminded of the seventy-two fragments of another dead body, that of Osiris, which was sought by Isis and found in the cypress-tree at Byblos. The oldest year is said to have been one of two seasons, or seventy-two weeks. Thus the body of Osiris would perhaps signify the whole year, divided into its most calculable units. In the more modern story we find ourselves dealing again with a number characteristic of the weeks of the year. The fragments of the body of Sat are fifty-two. Does she, then, represent some ancient personification which may have been the historic root of our present reckoning?

are fifty-two. Does she, then, represent some ancient personification which may have been the historic root of our present reckoning?

In a general way goddesses are, as we know, long anterior to gods, and it is interesting to see that in the older myth of Egypt it is the woman who is active, the woman who seeks and carries off the dead body of man. The comparative modernness of the story of Shiva and Sat is seen, amongst other things, in the fact that the husband seeks and finds and bears away the wife.

is seen, amongst other things, in the fact that the husband seeks and finds and bears away the wife.

Um

Sat was reborn as the daughter of the great mountain Himalaya, when her name was Um

was reborn as the daughter of the great mountain Himalaya, when her name was Um , surnamed Haim

, surnamed Haim vat

vat from her birth ; another name she had was P

from her birth ; another name she had was P rvat

rvat , daughter of the mountain. Her elder sister was the river Gang

, daughter of the mountain. Her elder sister was the river Gang . From her childhood Um

. From her childhood Um was devoted to Shiva, and she would steal away at night to offer flowers and fruits and to burn lights before the lingam. A deva, too, one day predicted that she would become the wife of the Great God. This awakened her father’s pride, and he was anxious that she should be betrothed; but nothing could be done, for Shiva remained immersed in profound contemplation, oblivious of all that went on, all his activity inward-turned. Um

was devoted to Shiva, and she would steal away at night to offer flowers and fruits and to burn lights before the lingam. A deva, too, one day predicted that she would become the wife of the Great God. This awakened her father’s pride, and he was anxious that she should be betrothed; but nothing could be done, for Shiva remained immersed in profound contemplation, oblivious of all that went on, all his activity inward-turned. Um became his servant and attended to all his requirements, but could not divert him from the practice of austerities or awaken his love. About this time a terrible demon named T

became his servant and attended to all his requirements, but could not divert him from the practice of austerities or awaken his love. About this time a terrible demon named T raka greatly harassed the gods and the world, perverting all seasons and destroying sacrifices ; nor could the gods defeat him, for in a past age he had won his power from Brahma himself by the practice of austerities. The gods therefore proceed to Brahma and pray his help. He explains that it would not be fitting for him to proceed against the demon, to whom he himself had given power; but he promises that a son should be born to Shiva and P

raka greatly harassed the gods and the world, perverting all seasons and destroying sacrifices ; nor could the gods defeat him, for in a past age he had won his power from Brahma himself by the practice of austerities. The gods therefore proceed to Brahma and pray his help. He explains that it would not be fitting for him to proceed against the demon, to whom he himself had given power; but he promises that a son should be born to Shiva and P rvat

rvat , who should lead the gods to victory.

, who should lead the gods to victory.

The chief of the gods, Indra, next betook himself to K madeva, or Desire, the god of Love, and explained the need of his assistance. Desire agreed to give his aid, and set out with his wife Passion and his companion the Spring to the mountain where Shiva dwelt. At that season the trees were putting forth new flowers, the snow had gone, and birds and beasts were mating; only Shiva stayed in his dream unmoved.

madeva, or Desire, the god of Love, and explained the need of his assistance. Desire agreed to give his aid, and set out with his wife Passion and his companion the Spring to the mountain where Shiva dwelt. At that season the trees were putting forth new flowers, the snow had gone, and birds and beasts were mating; only Shiva stayed in his dream unmoved.

Even Desire was daunted till he took new courage at the sight of Um ’s loveliness. He chose a moment when Shiva began to relax his concentration and when P

’s loveliness. He chose a moment when Shiva began to relax his concentration and when P rvat

rvat approached to worship him ; he drew his bow and was about to shoot when the Great God saw him and darted a flash of fire from his third eye, consuming Desire utterly. Shiva departed, leaving Passion unconscious, and P

approached to worship him ; he drew his bow and was about to shoot when the Great God saw him and darted a flash of fire from his third eye, consuming Desire utterly. Shiva departed, leaving Passion unconscious, and P rvat

rvat was carried away by her father. From that time Ananga, Bodiless, has been one of Kamadeva’s names, for he was not dead, and while Passion lamented her lost lord a voice proclaimed to her: “ Thy lover is not lost for evermore; when Shiva shall wed Um

was carried away by her father. From that time Ananga, Bodiless, has been one of Kamadeva’s names, for he was not dead, and while Passion lamented her lost lord a voice proclaimed to her: “ Thy lover is not lost for evermore; when Shiva shall wed Um he will restore Love’s body to his soul, a marriage gift to his bride.”

he will restore Love’s body to his soul, a marriage gift to his bride.”

P rvat

rvat now reproached her useless beauty, for what avails it to be lovely if no lover loves that loveliness ? She became a sanny

now reproached her useless beauty, for what avails it to be lovely if no lover loves that loveliness ? She became a sanny sin

sin , an anchorite, and laying aside all jewels, with uncombed hair and a hermit’s dress of bark, she retired to a lonely mountain and spent her life in meditation upon Shiva and the practice of austerities such as are dear to him. One day a Brahman youth visited her, offering congratulations upon the constancy of her devotion; but he asked her for what reason she thus spent her life in self-denial since she had youth and beauty and all that heart could desire. She related her story, and said that since Desire is dead she saw no other way to win Shiva’s approval than this devotion. The youth attempted to dissuade P

, an anchorite, and laying aside all jewels, with uncombed hair and a hermit’s dress of bark, she retired to a lonely mountain and spent her life in meditation upon Shiva and the practice of austerities such as are dear to him. One day a Brahman youth visited her, offering congratulations upon the constancy of her devotion; but he asked her for what reason she thus spent her life in self-denial since she had youth and beauty and all that heart could desire. She related her story, and said that since Desire is dead she saw no other way to win Shiva’s approval than this devotion. The youth attempted to dissuade P rvat

rvat from desiring Shiva, recounting the terrible stories of his inauspicious acts: how he wore a poisonous snake and a bloody elephant-hide, how he dwelt in cremation grounds, how he rode on a bull and was poor and of unknown birth. P

from desiring Shiva, recounting the terrible stories of his inauspicious acts: how he wore a poisonous snake and a bloody elephant-hide, how he dwelt in cremation grounds, how he rode on a bull and was poor and of unknown birth. P rvat

rvat was angered and defended her lord, finally declaring that her love could not be changed whatever was said of him, true or false. Then the young Brahman threw off his disguise and revealed himself as no other than Shiva, and he gave her his love. P

was angered and defended her lord, finally declaring that her love could not be changed whatever was said of him, true or false. Then the young Brahman threw off his disguise and revealed himself as no other than Shiva, and he gave her his love. P rvat

rvat then returned home to tell her father of her happy fortune, and the preliminaries of marriage were arranged in due form. At last the day came, both Shiva and his bride were ready, and the former, accompanied by Brahm

then returned home to tell her father of her happy fortune, and the preliminaries of marriage were arranged in due form. At last the day came, both Shiva and his bride were ready, and the former, accompanied by Brahm and Vishnu, entered Him

and Vishnu, entered Him laya’s city in triumphal procession, riding through the streets ankle-deep in scattered flowers, and Shiva bore away the bride to Kail

laya’s city in triumphal procession, riding through the streets ankle-deep in scattered flowers, and Shiva bore away the bride to Kail s; not, however, before he had restored the body of Desire to his lonely wife.

s; not, however, before he had restored the body of Desire to his lonely wife.

For many years Shiva and P rvat

rvat dwelt in bliss in their Himalayan paradise; but at last the god of fire appeared as a messenger from the gods and reproached Shiva that he had not begotten a son to save the gods from their distress. Shiva bestowed the fruitful germ on Fire, who bore it away and finally gave it to Ganges, who preserved it till the six Pleiades came to bathe in her waters at dawn. They laid it in a nest of reeds, where it became the godchild Kum

dwelt in bliss in their Himalayan paradise; but at last the god of fire appeared as a messenger from the gods and reproached Shiva that he had not begotten a son to save the gods from their distress. Shiva bestowed the fruitful germ on Fire, who bore it away and finally gave it to Ganges, who preserved it till the six Pleiades came to bathe in her waters at dawn. They laid it in a nest of reeds, where it became the godchild Kum ra, the future god of war. There Shiva and Parv

ra, the future god of war. There Shiva and Parv t

t found him again and took him to Kail

found him again and took him to Kail s, where he spent his happy childhood. When he had become a strong youth the gods requested his aid, and Shiva sent him as their general to lead an army against T

s, where he spent his happy childhood. When he had become a strong youth the gods requested his aid, and Shiva sent him as their general to lead an army against T raka. He conquered and slew the demon, and restored peace to Heaven and earth.

raka. He conquered and slew the demon, and restored peace to Heaven and earth.

The second son of Shiva and P rvat

rvat was Ganesha;15 he is the god of wisdom and the remover of obstacles. One day the proud mother, in a forgetful moment, asked the planet Saturn to look upon her son: his baleful glance reduced the child’s head to ashes. P

was Ganesha;15 he is the god of wisdom and the remover of obstacles. One day the proud mother, in a forgetful moment, asked the planet Saturn to look upon her son: his baleful glance reduced the child’s head to ashes. P rvat

rvat asked advice of Brahma, and he told her to replace the head with the first she could find : that was an elephant’s.

asked advice of Brahma, and he told her to replace the head with the first she could find : that was an elephant’s.

Um ’s Sport

’s Sport

Mah deva sat one day on a sacred mountain of Himalaya plunged in deep and arduous contemplation. About him were the delightful flowering forests, numerous with birds and beasts and nymphs and sprites. The Great God sat in a bower where heavenly flowers opened and blazed with radiant light; the scent of sandal and the sound of heavenly music were sensed on every side. Beyond all telling was the mountain’s loveliness, shining with the glory of the Great God’s penance, echoing with the hum of bees. All the Seasons were present there, and all creatures and powers resided there with minds firm-set in yoga, in concentred thought.

deva sat one day on a sacred mountain of Himalaya plunged in deep and arduous contemplation. About him were the delightful flowering forests, numerous with birds and beasts and nymphs and sprites. The Great God sat in a bower where heavenly flowers opened and blazed with radiant light; the scent of sandal and the sound of heavenly music were sensed on every side. Beyond all telling was the mountain’s loveliness, shining with the glory of the Great God’s penance, echoing with the hum of bees. All the Seasons were present there, and all creatures and powers resided there with minds firm-set in yoga, in concentred thought.

Mah deva had about his loins a tiger-skin and a lion’s pelt across his shoulders. His sacred thread was a terrible snake. His beard was green; his long hair hung in matted locks. The rishis bowed to the ground in worship; by that marvellous vision they were cleansed of every sin. There came Um

deva had about his loins a tiger-skin and a lion’s pelt across his shoulders. His sacred thread was a terrible snake. His beard was green; his long hair hung in matted locks. The rishis bowed to the ground in worship; by that marvellous vision they were cleansed of every sin. There came Um , daughter of Himalaya, wife of Shiva, followed by his ghostly servants. Garbed was she like her lord, and observed the same vows. The jar she bore was filled with the water of every t

, daughter of Himalaya, wife of Shiva, followed by his ghostly servants. Garbed was she like her lord, and observed the same vows. The jar she bore was filled with the water of every t rtha, and the ladies of the Sacred Rivers followed her. Flowers sprang up and perfumes were wafted on every side as she approached. Then Um

rtha, and the ladies of the Sacred Rivers followed her. Flowers sprang up and perfumes were wafted on every side as she approached. Then Um , with a smiling mouth, in playful mood covered the eyes of Mah

, with a smiling mouth, in playful mood covered the eyes of Mah deva, laying her lovely hands across them from behind.

deva, laying her lovely hands across them from behind.

Instantly life in the universe waned, the sun grew pale, all living things cowered in fear. Then the darkness vanished again, for one blazing eye shone forth on Shiva’s brow, a third eye like a second sun. So scorching a flame proceeded from that eye that Him laya was burnt with all his forests, and the herds of deer and other beasts rushed headlong to Mah

laya was burnt with all his forests, and the herds of deer and other beasts rushed headlong to Mah deva’s seat to pray for his protection, making the Great God’s power to shine with strange brightness. The fire meanwhile blazed up to the very sky, covering every quarter like the all-destroying conflagration of an æon’s end. In a moment the mountains were consumed, with all their gems and peaks and shining herbs. Then Him

deva’s seat to pray for his protection, making the Great God’s power to shine with strange brightness. The fire meanwhile blazed up to the very sky, covering every quarter like the all-destroying conflagration of an æon’s end. In a moment the mountains were consumed, with all their gems and peaks and shining herbs. Then Him laya’s daughter, beholding her father thus destroyed, came forth and stood before the Great God with her hands joined in prayer. Then Mah

laya’s daughter, beholding her father thus destroyed, came forth and stood before the Great God with her hands joined in prayer. Then Mah deva, seeing Um

deva, seeing Um ’s grief, cast benignant looks upon the mountain, and at once Him

’s grief, cast benignant looks upon the mountain, and at once Him laya was restored to his first estate, and became as fair as he had been before the fire. All his trees put forth their flowers, and birds and beasts were gladdened.

laya was restored to his first estate, and became as fair as he had been before the fire. All his trees put forth their flowers, and birds and beasts were gladdened.

Then Um with folded hands addressed her lord: “ O holy one, lord of creatures,” she said, “ I pray thee to resolve my doubt. Why did this third eye of thine appear? Why was the mountain burned and all its forests? Why hast thou now restored the mountain to his former state after destroying him ? ”

with folded hands addressed her lord: “ O holy one, lord of creatures,” she said, “ I pray thee to resolve my doubt. Why did this third eye of thine appear? Why was the mountain burned and all its forests? Why hast thou now restored the mountain to his former state after destroying him ? ”

Mah deva answered: “Sinless lady, because thou didst cover up my eyes in thoughtless sport the universe grew dark. Then, O daughter of the mountain, I created a third eye for the protection of all creatures, but the blazing energy thereof destroyed the mountain. It was for thy sake that I made Him

deva answered: “Sinless lady, because thou didst cover up my eyes in thoughtless sport the universe grew dark. Then, O daughter of the mountain, I created a third eye for the protection of all creatures, but the blazing energy thereof destroyed the mountain. It was for thy sake that I made Him laya whole again.”

laya whole again.”

Shiva’s Fishing

It befell one day that Shiva sat with P rvat

rvat in Kail

in Kail s expounding to her the sacred text of the Vedas. He was explaining a very difficult point when he happened to look up, and behold, P

s expounding to her the sacred text of the Vedas. He was explaining a very difficult point when he happened to look up, and behold, P rvat

rvat was manifestly thinking of something else ; and when he asked her to repeat the text she could not, for, in fact, she had not been listening. Shiva was very angry, and he said : “ Very well, it is clear you are not a suitable wife for a yog

was manifestly thinking of something else ; and when he asked her to repeat the text she could not, for, in fact, she had not been listening. Shiva was very angry, and he said : “ Very well, it is clear you are not a suitable wife for a yog ; you shall be born on earth as a fisherman’s wife, where you will not hear any sacred texts at all.” Immediately P

; you shall be born on earth as a fisherman’s wife, where you will not hear any sacred texts at all.” Immediately P rvat

rvat disappeared, and Shiva sat down to practise one of his deep contemplations. But he could not fix his attention; he kept on thinking of P

disappeared, and Shiva sat down to practise one of his deep contemplations. But he could not fix his attention; he kept on thinking of P rvat

rvat and feeling very uncomfortable. At last he said to himself : “ I am afraid I was rather hasty, and certainly P

and feeling very uncomfortable. At last he said to himself : “ I am afraid I was rather hasty, and certainly P rvat

rvat ought not to be down there on earth, as a fisherman’s wife too; she is my wife.” He sent for his servant Nandi and ordered him to assume the form of a terrible shark and annoy the poor fishermen, breaking their nets and wrecking their boats.

ought not to be down there on earth, as a fisherman’s wife too; she is my wife.” He sent for his servant Nandi and ordered him to assume the form of a terrible shark and annoy the poor fishermen, breaking their nets and wrecking their boats.

P rvat

rvat had been found on the seashore by the headman of the fishermen and adopted by him as his daughter. She grew up to be a very beautiful and gentle girl. All the young fishermen desired to marry her. By this time the doings of the shark had become quite intolerable; so the headman announced that he would bestow his adopted daughter in marriage upon whoever should catch the great shark. This was the moment foreseen by Shiva; he assumed the form of a handsome fisher-lad and, representing himself as a visitor from Madura, offered to catch the shark, and so he did at the first throw of the net. The fishermen were very glad indeed to be rid of their enemy, and the headman’s daughter was given in marriage to the young man of Madura, much to the disgust of her former suitors. But Shiva now assumed his proper form, and bestowing his blessing on P

had been found on the seashore by the headman of the fishermen and adopted by him as his daughter. She grew up to be a very beautiful and gentle girl. All the young fishermen desired to marry her. By this time the doings of the shark had become quite intolerable; so the headman announced that he would bestow his adopted daughter in marriage upon whoever should catch the great shark. This was the moment foreseen by Shiva; he assumed the form of a handsome fisher-lad and, representing himself as a visitor from Madura, offered to catch the shark, and so he did at the first throw of the net. The fishermen were very glad indeed to be rid of their enemy, and the headman’s daughter was given in marriage to the young man of Madura, much to the disgust of her former suitors. But Shiva now assumed his proper form, and bestowing his blessing on P rvat

rvat ’s foster-father, he departed with her once more to Kail

’s foster-father, he departed with her once more to Kail s. P

s. P rvat

rvat reflected that she really ought to be more attentive, but Shiva was so pleased to have P

reflected that she really ought to be more attentive, but Shiva was so pleased to have P rvat

rvat back again that he felt quite peaceful and quite ready to sit down and take up his interrupted dreams.

back again that he felt quite peaceful and quite ready to sit down and take up his interrupted dreams.

THE SAINTS OF SHIVA Tiger-foot (Vyaghrap da)

da)

A certain pure and learned Brahman dwelt beside the Ganges. He had a son endowed with strange powers and gifts of mind and body. He became the disciple of his father; when he had learnt all that his father could teach him, the sage bestowed his blessing, and inquired of his son: “What remains that I can do for thee?” Then the son bowed down to his father’s feet, saying: “Teach me the highest form of virtue amongst those of the hermit rule.” The father answered: “The highest virtue is to worship Shiva.” “Where best may I do that?” asked the youth. The father answered: “ He pervades the whole universe; yet there are places on earth of special manifestation, even as the all-pervading Self is manifest in individual bodies. The greatest of such shrines is Tillai, where Shiva will accept thy adoration; there is the lingam of pure light.”

The young ascetic left his parents and set out on his long journey to the south. Presently he came to a beautiful lake covered with lotus-flowers, and beside it he saw a lingam under a banyan-tree. He fell on his face in adoration of the lord and made himself its priest, doing the service of offering flowers and water with unfailing devotion day by day. Not far away he built himself a little hermitage and established a second lingam in the forest. But now he found it difficult to accomplish perfectly the service of both shrines. For he was not content with the flowers of pools and fields and shrubs, but desired to make daily offering of the most exquisite buds from the summits of the lofty forest trees. However early he would start, still the sun’s fierce rays withered half of these before he could gather enough, nor could he see in the dark hours how to choose the most perfect flowers.

In despair of perfect service he cast himself upon the ground and implored the god to help him. Shiva appeared and, with a gentle smile, bestowed a boon on the devoted youth. He prayed that he might receive the hands and feet of a tiger, armed with strong claws and having keen eyes set in them, that he might quickly climb the highest trees and find the most perfect flowers for the service of the shrine. This Shiva granted, and thus the youth became the “ Tiger-footed ” and the “ Six-eyed.”

Eye-Saint (Kan-Appan)

There dwelt long ago a forest chieftain who spent all his days in hunting, so that the woods resounded with the barking of his dogs and the cries of his servants. He was a worshipper of Subrahmanian, the southern mountain deity, and his offerings were strong drink, cocks and peafowl, accompanied with wild dances and great feasts. He had a son, surnamed the Sturdy, whom he took always with him on his hunting expeditions, giving him the education, so they say, of a young tiger-cub. The time came when the old chief grew feeble, and he handed over his authority to the Sturdy one.

He also spent his days in hunting. One day a great boar made his escape from the nets in which he had been taken and rushed away. The Sturdy one followed with two servants, a long and weary chase, till at last the boar fell down from very weariness, and Sturdy cut it atwain. When the retinue came up they proposed to roast the boar and take their rest; but there was no water, so Sturdy shouldered the boar and they went farther afield. Presently they came in sight of the sacred hill of Kala-harti ; one of the servants pointed to its summit, where there was an image of the god with matted locks. “Let us go there to worship,” he said. Sturdy lifted the boar again and strode on. But as he walked the boar grew lighter and lighter, rousing great wonder in his heart.

He laid the boar down and rushed on to seek the meaning of the miracle. It was not long before he came to a stone lingam, the upper part of which was shaped into the likeness of the god’s head; immediately it spoke to his soul, prepared by some goodness or austerity of a previous birth, so that his whole nature was changed, and he thought of nothing but the love of the god whom now he first beheld; he kissed the image, like a mother embracing a long-lost son. He saw that water had recently been poured upon it, and the head was crowned with leaves; one of his followers, just coming up, said that this must have been done by an old Brahman devotee who had dwelt near by in the days of Sturdy’s father.

It came into Sturdy’s heart then that perhaps he himself might render some service to the god. He could scarcely bring himself to leave the image all alone; but he had no other choice, and hurrying back to the camp, he chose some tender parts of the roasted flesh, tasted them to see if they were good, and taking these in a cup of leaves and some water from the river in his mouth, he ran back to the image, leaving his astonished followers without a word, for they naturally thought he had gone mad. When he reached the image he sprinkled it with water from his mouth, made offering of the boar’s flesh and laid upon it the wild flowers from his own hair, praying the god to receive his gifts. Then the sun went down, and Sturdy remained beside the image on guard with bow strung and arrow notched. At dawn he went forth to hunt that he might have new offerings to lay before the god.

Meanwhile the Brahman devotee who had served the god so many years came to perform his customary morning service; he brought pure water in a sacred vessel, fresh flowers and leaves, and recited holy prayers. What was his horror to see that the image had been defiled with flesh and dirty water! He rolled in grief before the lingam, asking the Great God why he had allowed this pollution of his shrine, for the offerings acceptable to Shiva are pure water and fresh flowers; it is said that there is greater merit in laying a single flower before the god than in offering much gold. For this Brahman priest the slaying of creatures was a hideous crime, the eating of flesh an utter abomination, the touch of a man’s mouth horrible pollution, and he looked on the savage woodland hunters as a lower order of creation. He reflected, however, that he must not delay to carry out his own customary service, so he cleansed the image carefully and did his worship according to the Vedic rite as usual, sang the appointed hymn, circumambulated the shrine, and returned to his abode.

For some days this alternation of service of the image took place, the Brahman offering pure water and flowers in the morning, the hunter bringing flesh at night. Meanwhile Sturdy’s father arrived, thinking his son possessed, and strove to reason with the young convert; but it was in vain, and they could but return to their village and leave him alone.

The Brahman could not bear this state of things for long; passionately he called on Shiva to protect his image from this daily desecration. One night the god appeared to him, saying: “That of which thou dost make complaint is acceptable and welcome to me. He who offers flesh and water from his mouth is an ignorant hunter of the woods who knows no sacred lore. But regard not him, regard his motive alone; his rough frame is filled with love of me, that very ignorance is his knowledge of myself. His offerings, abominable in thy eyes, are pure love. But thou shalt behold to-morrow the proof of his devotion.”

Next day Shiva himself concealed the Brahman behind the shrine; then, in order to reveal all the devotion of Sturdy, he caused the likeness of blood to flow from one eye of the image of himself. When Sturdy brought his customary offering, at once he saw this blood, and he cried out: “ O my master, who hath wounded thee? Who has done this sacrilege when I was not here to guard thee?” Then he searched the whole forest to seek for the enemy; finding no one, he set himself to stanch the wound with medicinal herbs ; but in vain. Then he remembered the adage of the doctors, that like cures like, and at once he took a keen-edged arrow and cut out his own right eye and applied it to the eye of the image of the god ; and lo ! the bleeding ceased at once. But, alas ! the second eye began to bleed. For a moment Sturdy was cast down and helpless; then it flashed upon him that he still had the means of cure, of proved efficacy. He seized the arrow and began to cut away his other eye, putting his foot against the eye of the image, so that he might not fail to find it when he could no longer see.

But now Shiva’s purpose was accomplished; he put forth a hand from the lingam and stayed the hunter’s hand, saying to him : “ It is enough; henceforth thy place shall be for ever by my side in Kail s.” Then the Brahman priest also saw that love is greater than ceremonial purity ; and Sturdy has been evermore adored as Eye-Saint.

s.” Then the Brahman priest also saw that love is greater than ceremonial purity ; and Sturdy has been evermore adored as Eye-Saint.

M nikka V

nikka V çagar and the Jackals

çagar and the Jackals

This saint was born near Madura; by his sixteenth year he had exhausted the whole circle of contemporary Brahman learning, especially the Shaiva scriptures; the report of his learning and intelligence reached the king, who sent for him and made him prime minister. At the P ndian court he enjoyed the luxury of Indra’s heaven, and moved amongst the courtiers like the silver moon amongst the stars, arrayed in royal robes, surrounded by horses and elephants, attended by the umbrella of state; for the wise king left the government entirely in his hands. Still the young minister did not lose his head; he reminded himself that these external pleasures are but bonds of the soul, and must be forsaken by those who would obtain Release. He felt great compassion for the toiling multitudes who pass from birth to birth suffering remediless griefs. His soul melted in passionate longing for Shiva. He continued to administer justice and to rule well, but ever hoped to meet with a Master who would reveal to him the “ Way of Release.” Like the bee that flits from flower to flower, he went from one to another of the Shaiva teachers, but found no satisfying truth. One day a messenger came to court announcing that a ship had arrived in the harbour of a neighbouring king bringing a cargo of splendid horses from abroad. The king at once dispatched his minister with great treasure to buy the beautiful horses, and he set out in state, attended by regiments of soldiers. This was the last great pageant of his secular life.

ndian court he enjoyed the luxury of Indra’s heaven, and moved amongst the courtiers like the silver moon amongst the stars, arrayed in royal robes, surrounded by horses and elephants, attended by the umbrella of state; for the wise king left the government entirely in his hands. Still the young minister did not lose his head; he reminded himself that these external pleasures are but bonds of the soul, and must be forsaken by those who would obtain Release. He felt great compassion for the toiling multitudes who pass from birth to birth suffering remediless griefs. His soul melted in passionate longing for Shiva. He continued to administer justice and to rule well, but ever hoped to meet with a Master who would reveal to him the “ Way of Release.” Like the bee that flits from flower to flower, he went from one to another of the Shaiva teachers, but found no satisfying truth. One day a messenger came to court announcing that a ship had arrived in the harbour of a neighbouring king bringing a cargo of splendid horses from abroad. The king at once dispatched his minister with great treasure to buy the beautiful horses, and he set out in state, attended by regiments of soldiers. This was the last great pageant of his secular life.

Meanwhile Shiva himself, as he sat in his court in Heaven with Um by his side, announced his intention to descend to earth in the shape of a human guru or Master, that he might initiate a disciple for the conversion of the South and the glory of the Tamil speech. He took his seat accordingly under a great spreading tree, surrounded by many servants in the form of Shaiva saints, his disciples. At his advent the trees put forth their blossoms, the birds sang on every branch of the grove near by the seaport where the lord had taken his seat. Then the young envoy passed by, attended by his retinue, and heard the sound of Shaiva hymns proceeding from the grove. He sent a messenger to learn the source of the divine music, and was told that there was seated a saintly Master, like to Shiva himself, beneath a great tree, attended by a thousand devotees. He dismounted and proceeded reverently toward the sage, who appeared to his vision like Shiva himself, with his blazing third eye. He made inquiries as to the divine truths taught by the sage and his disciples; he was converted and threw himself at the Master’s feet in tears, renouncing all worldly honour; he received a solemn initiation, and became a J

by his side, announced his intention to descend to earth in the shape of a human guru or Master, that he might initiate a disciple for the conversion of the South and the glory of the Tamil speech. He took his seat accordingly under a great spreading tree, surrounded by many servants in the form of Shaiva saints, his disciples. At his advent the trees put forth their blossoms, the birds sang on every branch of the grove near by the seaport where the lord had taken his seat. Then the young envoy passed by, attended by his retinue, and heard the sound of Shaiva hymns proceeding from the grove. He sent a messenger to learn the source of the divine music, and was told that there was seated a saintly Master, like to Shiva himself, beneath a great tree, attended by a thousand devotees. He dismounted and proceeded reverently toward the sage, who appeared to his vision like Shiva himself, with his blazing third eye. He made inquiries as to the divine truths taught by the sage and his disciples; he was converted and threw himself at the Master’s feet in tears, renouncing all worldly honour; he received a solemn initiation, and became a J van-mukta, one who attains Release even while still incarnate in human form. He adopted the white ashes and braided locks of a Shaiva yogi. Moreover, he made over to the Master and his attendants all the treasure entrusted to him for the purchase of the horses.

van-mukta, one who attains Release even while still incarnate in human form. He adopted the white ashes and braided locks of a Shaiva yogi. Moreover, he made over to the Master and his attendants all the treasure entrusted to him for the purchase of the horses.

The noble retinue now approached the converted minister, and remonstrated with this disposal of his master’s property; but he bade them depart, “ for why,” he asked, “would you bring me back to mundane matters such as this?” They therefore returned to Madura and announced to the king what had taken place. He was not unnaturally enraged, and sent a curt order for the minister’s immediate return. He only answered : “ I know no king but Shiva, from whom not even the messengers of Death could lead me.” Shiva, however, bade him return to Madura and fear nothing, but to say that the horses would arrive in due course. The god also provided him with a suitable equipage and a priceless ruby. The king at first accepted his assurances that the horses would arrive; but the story of the other courtier prevailed, and two days before the promised arrival of the horses the young minister was thrown into prison.

The lord, however, cared for his disciple. He gathered together a multitude of jackals, converted them into splendid horses, and sent them to court, with hosts of minor deities disguised as grooms; he himself rode at the head of the troops, disguised as the merchant from whom the horses were supposed to have been purchased. The king was of course delighted, and released the minister with many apologies. The horses were delivered and sent to the royal stables; the disguised gods departed, and all seemed well.

Before dawn the town was aroused by awful howlings ; the horses had turned into jackals and, worse still, were devouring the real horses in the king’s stables. The king perceived that he had been deceived, and seized the wretched minister and had him exposed to the noonday sun, with a heavy stone upon his back. He prayed to his lord; Shiva in answer released the waters of Gang from his matted locks and flooded the town. Again the king perceived his error; he restored the sage to a place of honour, and set about erecting a dam to save the town. When this was accomplished, the king offered to resign his kingdom to the saint; but M

from his matted locks and flooded the town. Again the king perceived his error; he restored the sage to a place of honour, and set about erecting a dam to save the town. When this was accomplished, the king offered to resign his kingdom to the saint; but M nikka V

nikka V çagar preferred to retire to the seaport where he first beheld the lord. There he took up his place at the feet of the guru. Shiva’s work, however, was now accomplished; he departed to Heaven, leaving it a charge upon M

çagar preferred to retire to the seaport where he first beheld the lord. There he took up his place at the feet of the guru. Shiva’s work, however, was now accomplished; he departed to Heaven, leaving it a charge upon M nikka V

nikka V çagar to establish the faith throughout Tamilakam. Thereafter the saint spent his life in wandering from town to town, singing the impassioned devotional hymns from which is derived his name of “ Him whose Utterance is Rubies.” At last he reached Chitambaram, the sacred city where Shiva’s dance is daily beheld, the abode also of the saint named Tiger-foot; here the sage dwelt until his passing away into the lord. This was the manner of that beatification. After a great controversy with Buddhist heretics from Ceylon there appeared a venerable but unknown devotee who prayed to be allowed to write down all the saint’s songs from his own lips. This he did, and then disappeared; for it was no other than Shiva himself, who took the songs to heaven for the gladdening of the gods. Next morning a perfect copy was found, a thousand verses in all, signed by the god himself, beside his image in Chitambaram. All the devotees of the temple hastened to the saint for an explanation ; he told them to follow him, and led them to the image of Shiva in the Golden Court. “That is the meaning,” he said, and therewith he disappeared, melting into the image itself, and he was seen no more.

çagar to establish the faith throughout Tamilakam. Thereafter the saint spent his life in wandering from town to town, singing the impassioned devotional hymns from which is derived his name of “ Him whose Utterance is Rubies.” At last he reached Chitambaram, the sacred city where Shiva’s dance is daily beheld, the abode also of the saint named Tiger-foot; here the sage dwelt until his passing away into the lord. This was the manner of that beatification. After a great controversy with Buddhist heretics from Ceylon there appeared a venerable but unknown devotee who prayed to be allowed to write down all the saint’s songs from his own lips. This he did, and then disappeared; for it was no other than Shiva himself, who took the songs to heaven for the gladdening of the gods. Next morning a perfect copy was found, a thousand verses in all, signed by the god himself, beside his image in Chitambaram. All the devotees of the temple hastened to the saint for an explanation ; he told them to follow him, and led them to the image of Shiva in the Golden Court. “That is the meaning,” he said, and therewith he disappeared, melting into the image itself, and he was seen no more.

A Legend of Shiva’s Dance

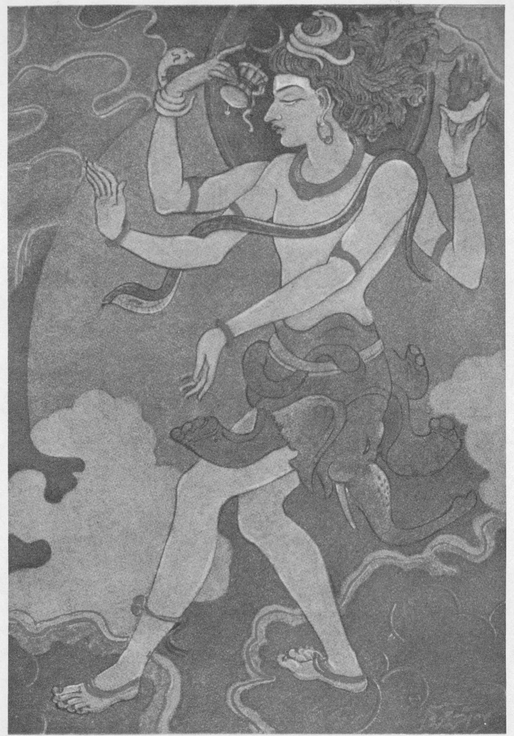

It came to the knowledge of Shiva that there resided in T ragam forest ten thousand heretical rishis, who taught that the universe is eternal, that souls have no lord, and that the performance of works alone suffices for the attainment of salvation. Shiva determined to teach them the truth. He bade Vishnu accompany him in the form of a beautiful woman, and the two entered the wild forest, Shiva disguised as a wandering yogi, Vishnu as his wife. Immediately all the rishis’ wives were seized with violent longing for the yogi; the rishis themselves were equally infatuated with the seeming yogi’s wife. Soon the whole hermitage was in an uproar; but presently the hermits began to suspect that things were not quite what they seemed; they gathered together, and pronounced quite ineffectual curses on the visitors. Then they prepared a sacrificial fire, and evoked from it a terrible tiger which rushed upon Shiva to devour him. He only smiled, and gently picking it up, he peeled off its skin with his little finger, and wrapped it about himself like a silk shawl. Then the rishis produced a horrible serpent; but Shiva hung it round his neck for a garland. Then there appeared a malignant black dwarf with a great club; but Shiva pressed his foot upon its back and began to dance, with his foot still pressing down the goblin. The weary hermits, overcome by their own efforts, and now by the splendour and swiftness of the dance and the vision of the opening heavens, the gods having assembled to behold the dancer, threw themselves down before the glorious god and became his devotees.

ragam forest ten thousand heretical rishis, who taught that the universe is eternal, that souls have no lord, and that the performance of works alone suffices for the attainment of salvation. Shiva determined to teach them the truth. He bade Vishnu accompany him in the form of a beautiful woman, and the two entered the wild forest, Shiva disguised as a wandering yogi, Vishnu as his wife. Immediately all the rishis’ wives were seized with violent longing for the yogi; the rishis themselves were equally infatuated with the seeming yogi’s wife. Soon the whole hermitage was in an uproar; but presently the hermits began to suspect that things were not quite what they seemed; they gathered together, and pronounced quite ineffectual curses on the visitors. Then they prepared a sacrificial fire, and evoked from it a terrible tiger which rushed upon Shiva to devour him. He only smiled, and gently picking it up, he peeled off its skin with his little finger, and wrapped it about himself like a silk shawl. Then the rishis produced a horrible serpent; but Shiva hung it round his neck for a garland. Then there appeared a malignant black dwarf with a great club; but Shiva pressed his foot upon its back and began to dance, with his foot still pressing down the goblin. The weary hermits, overcome by their own efforts, and now by the splendour and swiftness of the dance and the vision of the opening heavens, the gods having assembled to behold the dancer, threw themselves down before the glorious god and became his devotees.

XXIV

THE DANCE OF SHIVA

KHITINDRA N TH MAZUMDAR

TH MAZUMDAR

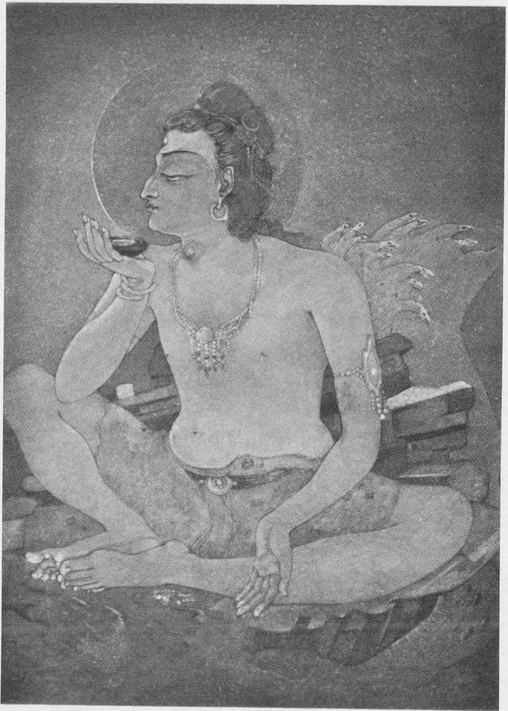

XXV

SHIVA DRINKING THE WORLD-POISON

NANDA L L BOSE

L BOSE

Now P rvat

rvat descended on the white bull, and Shiva departed with her to Kail

descended on the white bull, and Shiva departed with her to Kail s. Vishnu was thus left alone with his attendant, the serpent At close hand, Ananta, the Infinite, upon whom he rests on the ocean of milk during the night of Brahma. Each was dazed with the beauty of Shiva’s dance, and Ati-Sheshan especially longed to see the vision again. Vishnu therefore released the serpent from his service, appointing his son to take his place; he advised his late servant to repair to Kail

s. Vishnu was thus left alone with his attendant, the serpent At close hand, Ananta, the Infinite, upon whom he rests on the ocean of milk during the night of Brahma. Each was dazed with the beauty of Shiva’s dance, and Ati-Sheshan especially longed to see the vision again. Vishnu therefore released the serpent from his service, appointing his son to take his place; he advised his late servant to repair to Kail s and to obtain the favour of Shiva by a life of asceticism. So the serpent devotee, with his thousand jewelled heads, departed to the northern regions to lay aside his secular glory and become the least of Shiva’s devotees. After a time, Shiva, assuming the form of Brahma riding upon his swan, appeared to test the devotee’s sincerity; he pointed out that already enough had been endured to merit the delights of paradise and a high place in Heaven, and he offered a boon. But the serpent answered: “ I desire no separate heaven, nor miraculous gifts; I desire only to see for ever the mystic dance of the Lord of all.” Brahma argued with him in vain; the serpent will remain as he is, if need be until death and throughout other lives, until he obtains the blessed vision. Shiva then assumed his own form, and riding beside P

s and to obtain the favour of Shiva by a life of asceticism. So the serpent devotee, with his thousand jewelled heads, departed to the northern regions to lay aside his secular glory and become the least of Shiva’s devotees. After a time, Shiva, assuming the form of Brahma riding upon his swan, appeared to test the devotee’s sincerity; he pointed out that already enough had been endured to merit the delights of paradise and a high place in Heaven, and he offered a boon. But the serpent answered: “ I desire no separate heaven, nor miraculous gifts; I desire only to see for ever the mystic dance of the Lord of all.” Brahma argued with him in vain; the serpent will remain as he is, if need be until death and throughout other lives, until he obtains the blessed vision. Shiva then assumed his own form, and riding beside P rvat

rvat on their snow-white bull, he approached the great snake and touched his head.

on their snow-white bull, he approached the great snake and touched his head.

Then he proceeded like an earthly guru—and for the Shaivites every true Master is an incarnation of God—to impart ancient wisdom to his new disciple. The universe, he said, is born of Maya, illusion, to be the scene of countless incarnations and of actions both good and evil. As an earthen pot has for its first cause the potter, for material cause the clay, and instrumental cause the potter’s staff and wheel, so the universe has illusion for its material cause, the Shakti of Shiva—that is, P rvat

rvat —for its instrumental cause, and Shiva himself for its first cause. Shiva has two bodies, the one with parts and visible, the other without parts, invisible and transcendental. Beyond these again is his own essential form of light and splendour. He is the soul of all, and his dance is the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe, and the giving of bodies to souls and their release. The dance is ceaseless and eternal ;

—for its instrumental cause, and Shiva himself for its first cause. Shiva has two bodies, the one with parts and visible, the other without parts, invisible and transcendental. Beyond these again is his own essential form of light and splendour. He is the soul of all, and his dance is the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe, and the giving of bodies to souls and their release. The dance is ceaseless and eternal ;  ti-Sheshan shall behold it again at Tillai, Chitambaram, the centre of the universe. “ Meanwhile,” said Shiva, “ thou shalt put off thy serpent form and, born of mortal parents, shalt proceed to Tillai, where thou shalt find a grove, where is a lingam, the first of all lingams, tended by my servant Tiger-foot. Dwell with him in the hermitage that he has made, and there shall come a time when the dance shall be revealed to thee and him together.”