THE SABBATS OF THE OLD DAYS HAVE COME TO LIFE IN A NEW FORM— THE OUTDOOR ROCK FESTIVAL. BOTH SERVE AS A CATHARTIC RELEASE FROM THE DRUDGERIES OF DAILY SECULAR EXISTENCE. THOSE YOUNG PEOPLE IN ATTENDANCE AT THE CONCERTS ARE, FOR THE MOST PART, THOSE WHO LABEL THEMSELVES PROUDLY THE “NEW GENERATION,” THOSE WHO, LIKE THE EUROPEAN SERF, FEEL A PROFOUND SCHISM BETWEEN THEMSELVES AND THE ESTABLISHMENT. AT THE CONCERTS, AS AT THE SABBATS, THERE IS THROBBING, HYPNOTIC MUSIC, WIDESPREAD USE OF HALLUCINOGENIC DRUGS BY THE CELEBRANTS, AN ESCAPE INTO ANIMALITY...

—ARTHUR LYONS,

THE SECOND COMING11

SYMPATHIES FOR THE DEVIL

THE DEVIL HAS ALWAYS TREASURED MUSIC. WHAT BETTER ARENA to inspire, cultivate, and propagate his will into the affairs of man? Music serves as both balm and excitant, soothing the savage or awakening dormant passions. In spiritual terms music is a magical operation, a vehicle for man to communicate with the gods. Depending on whom the celebrants invoke, this can mean soaring to heaven on the voices of angels or raising beasts from the pits of hell.

With the ascendency of Christianity in the Western world over the past two millennia, music has always been a problematic area for both religious and secular authority. While song has often served to bind the Lord’s supplicants, its seductive words and cadences may just as easily sow seeds of doubt in the mind. Mephistopheles and the Muse go hand in hand, and the folk songs of old often extol wine, women, and song—all three the Devil’s playthings. Many of the oldest known songs in European tradition derive from heathen, pre-Christian roots, and spin tales of magic, necromancy, and superstition. It is no wonder the Christian Church did its best to try to supplant such songs of the people with hymns extolling its own icons and ideals; nevertheless, tradition dies hard and has a way of resurfacing despite all attempts to discourage or silence it.

Self-proclaimed moral authorities continue to frown upon the ecstasies of revelry and lusty song, attempting to root them out. In the first half of the twentieth century, Jazz was considered particularly dangerous, with its imagined potential to unleash animal passions, especially among unsuspecting white folk. Theosophical writers on the occult significance of music even go so far as to state that the force ushering Jazz into the nightclubs could be none other than that which allows evil to operate on earth. In his book on the Rolling Stones,

Dance With the Devil, Stanley Booth quotes the

New Orleans Times-Picayune in 1918: “On certain natures sound loud and meaningless has an exciting, almost an intoxicating effect, like crude colors and strong perfumes, the sight of flesh or the sadic pleasure in blood. To such as these the jass music is a delight [sic].”

2 Early lurid scare tactics had little effect, and Jazz attracted a more genteel audience as time went on.

More directly tied to deviltry than Jazz, and likewise imbued with the potency of its racial origins, was Blues. Black slaves often adopted Christianity after their enforced arrival in America, but melded it with native or Voudoun strains. Blues songs abound with references to devils, demons, and spirits. One of the most influential Blues singers of all time, Robert Johnson, is said to have sold his soul to the Devil at a crossroads in the Mississippi Delta, and the surviving recordings of his haunting songs give credence to the legend that Satan rewarded his pact with the ability to play. Johnson recorded only twenty-nine tunes, some of the more famous being “Crossroads Blues,” “Me and the Devil Blues,” and “Hellhound on My Trail.” The leaden resignation of his music is a genuine reflection of his existence. Life for Johnson began on the plantations, wound through years of carousing and playing juke joints, ending abruptly in 1938 when at the age of 27 he was poisoned in a bar, probably as a result of an affair with the club owner’s wife. Johnson’s musical legacy would fade into obscurity until reissued on LPs in the ’60s, when it found a new excited audience among the Blues Rock musicians of that era. From the demonic songs of Delta Blues one can trace a line to the present world of Satanic Rock and Roll.

LUCIFER TURNS UP THE VOLUME

Most early Rock—despite the power commanded over youth by Elvis “the pelvis” Presley and the Beatles—was, in reality, only mildly threatening to the status quo. Its most anti-social element came from the thugs and delinquents who latched onto Rockabilly, but chances are these youths would have been stealing cars and rolling bums no matter what kind of music they listened to. As the ’60s spiraled onward, musical experimentation coupled with drug use, and a decidedly darker element came to the fore.

The Beatles appeared downright tidy next to Rolling Stones, who reveled in the role of international bad boys—boozers, fighters, and satyr-like icons of sensual excess. By no accident the Stones traced their musical lineage back to Robert Johnson and his infernal Delta swamp Blues. The Stones took their diabolical inspiration seriously, deliberately cultivating a Satanic image, from wearing Devil masks in promotional photos to conjuring up sinister album titles such as Their Satanic Majesties Request and Let it Bleed. The band’s lyrics ambivalently explored drug addiction, rape, murder, and predation. The infamous culmination of these flirtations revealed itself at the Altamont Speedway outdoor festival on December 6, 1969. Inadvertently captured on film in the live documentary Gimme Shelter, it was only moments into the song “Sympathy for the Devil” before all hell broke loose between the legion of Hell’s Angels “security guards” and members of the audience, ending with the fatal stabbing of Meredith Hunter, a gun-wielding black man in the crowd. The infernal, violent chaos of the event at Altamont made it abundantly clear the peace and love of the ’60s wouldn’t survive the transition to a new decade.

Simultaneously with the ascension of the Rolling Stones to world fame, other English Rock groups entered the scene, bringing with them even more developed elements of the occult and black magic. Flower Power was a period of spiritual desperation for a vast section of youth in Britain and America, throwing off the Christianity of previous generations while seeking something truer to their nature with dabbling in Eastern mysticism and innumerable cults and sects. Occult faddism, largely dormant since the first decades of the century, began to manifest widely.

English black magician Aleister Crowley, dubbed the “wickedest man in the world” by the press in the 1930s, now rose to higher influence and prominence than he had ever experienced in his own lifetime. Through the underground films of Kenneth Anger, Crowley’s specter began to loom large over the end of the ’60s and early ’70s. Both Mick Jagger of the Stones and Jimmy Page, guitarist of Led Zeppelin, scored soundtracks for Anger’s Crowley-inspired films Invocation of My Demon Brother and Lucifer Rising, the titles of which betray their mystical concerns. Page’s interest in Crowley developed to a far more serious level than the Satanic dabbling of the Stones; his collection of original Crowley books and manuscripts is among the best in the world. Page held a financial share in the Equinox occult bookshop (named after the hefty journal of “magick” Crowley edited and published between 1909–14) in London and at one point even purchased Crowley’s former Scottish Loch Ness estate, Boleskine. The property continued to perpetuate its sinister reputation under new ownership, as caretakers were confined to mental asylums, or worse, committed suicide during their tenures there.

The bad vibes came with the territory. Speaking of his attraction to the strong-arm philosophy of Machiavelli in an interview, Page declared, “He was a master of evil, but you can’t ignore evil if you study the supernatural as I do ... I want to go on studying it.”

3 He was also straightforward in admiration for his spiritual mentor: “I think Aleister Crowley’s completely relevant to today. We’re all still seeking for truth—the search goes on ... Magic is very important if people can go through with it.”

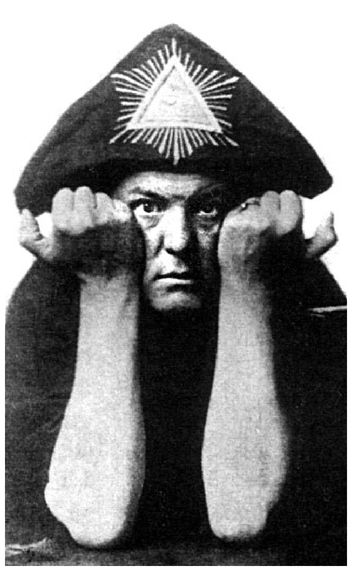

4ALEISTER CROWLEY

Imagery of Crowley’s Thelemic religion can be found woven throughout the albums of Led Zeppelin, along with influences drawn from Anglo-Saxon and Norse heathen folklore and traditional music, and the mythology of J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary works. If there is any early Rock band bearing exemplifying the basic themes that would later preoccupy many of the Black Metal bands in the ’90s, it is Led Zeppelin. Stephen Davis, author of the Zeppelin rockography

Hammer of the Gods, remarks that the music for the song “No Quarter,” which Page composed, “inspired Robert [Plant] to write lyrics with provocative images of Led Zeppelin as a Viking death squad riding the winds of Thor to some awful Satanic destiny.”

5The group encouraged such impressions with some of their antics, staging a record release party in the guise of a mock Black Mass. The event was held in the underground caves which formerly housed similar rites perpetrated by Sir Francis Dashwood and his debauched Hellfire Club two centuries earlier. In their heyday, the band—and Page especially—knew the value of a nasty reputation, much as Crowley had in his own generation. The resulting rumors ranged from the old standby of an alleged pact with the Devil signed by the group in return for success, to stories of Page’s experiments with black magic effecting the death of drummer John Bonham. In recent years the former members of Led Zeppelin have tried to downplay such interests, with Plant and Page dismissing the Boleskine property as nothing more than an old “pig farm.”

6Whether Zeppelin was in fact a “Heavy Metal” band is a point of debate, although they pioneered a sound which must be acknowledged as such in its more thunderous moments. Whether Black Sabbath is a Heavy Metal group there is no room for doubt. Sabbath slowed the contemporary framework of Blues-based Rock down to a lurching, sinister pace which perfectly suited their lyrical themes of insanity, war, and alienation. Singer Ozzy Ozbourne pioneered a haunting wail and the rest of the band made little effort to concede to any of the cheery sentiments still floating on hippy lips. Sabbath’s cover art brought Satanic imagery to its apex in mainstream pop culture of the early ’70s, with eerie demons attacking sleeping humans on albums like Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath.

Although members of the band talk of the occult, and Ozzy Ozbourne later in his solo career wrote his own paean to the “Great Beast” with the song “Mr. Crowley,” a closer look at the lyrics of Black Sabbath does not uncover any serious Satanic philosophy. To the contrary, it reveals an almost Christian fear of demons and sorcery. In a 1996 interview with journalist Steve Blush in Seconds magazine, Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler explains the truth of the band’s connection to the occult:

I was really interested because I was brought up Catholic. When I was a kid, I was a religious maniac. I loved anything to do with religion and God. Being a Catholic, every week you hear what the Devil does and “Satan’s this” and “Satan’s that,” so you really believe in it. What sparked my interest was when I was in London around 1966–67. There was a whole new culture happening and this one guy used to sell these black magic magazines. I read a magazine and thought, “Oh yeah, I never thought of it like that”—Satan’s point of view. I just started reading more and more; I read a lot of Dennis Wheatley’s books, stuff about astral planes. I’d been having loads of these experiences since I was a child and finally I was reading stuff that was explaining them. It lead me into reading about the whole thing—black magic, white magic, every sort of magic. I found out Satanism was around before any Christian or Jewish religion. It’s an incredibly interesting subject. I sort of got more into the black side of it and was putting upside-down crosses on my wall and pictures of Satan all over. I painted my apartment black. I was getting really involved in it and all these horrible things started happening to me. You come to a point where you cross over and totally follow it and totally forget about Jesus and God. “Are you going to do it? Yes or no?” No, I don’t think so.

7

Black Sabbath’s flirtation with evil, filtered to their fans through a haze of barbiturates and Quaaludes, cemented them as a band tapped into the dark current. Like Led Zeppelin, the sinister image took hold and would be with them forever. Without respect or support from the press, Black Sabbath were filling arenas around the world, leaving their mark on impressionable kids who swarmed to have their eardrums pummeled in these rituals of crushing sound and volume.

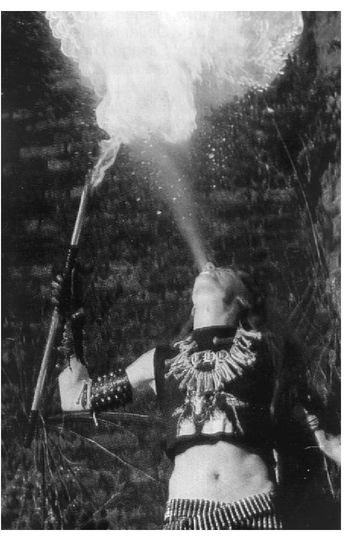

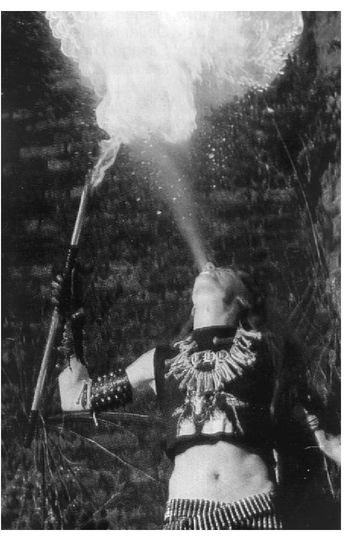

Groups further from the spotlight than Black Sabbath—such as Black Widow and Coven—could afford to be even more obsessive in their imagery. The English sextet Black Widow released three diaphanous Hard Rock albums between 1970–72, and later appe"ar as a footnote in books that cover the history of occultism in pop culture. The chanting refrain of their song “Come to the Sabbat” evokes images of their concerts which featured a mock ritual sacrifice as part of the show. Beyond sketchy tales of such events, and the few recordings and photos they’ve left behind, Black Widow remains shrouded in mystery.

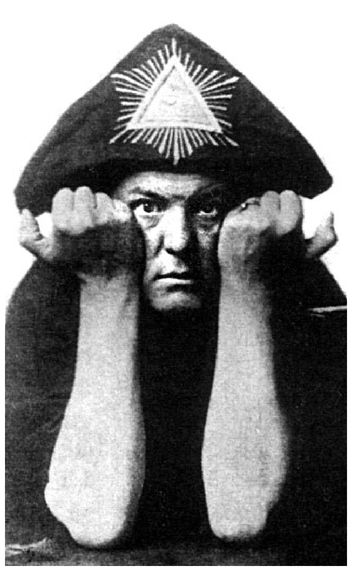

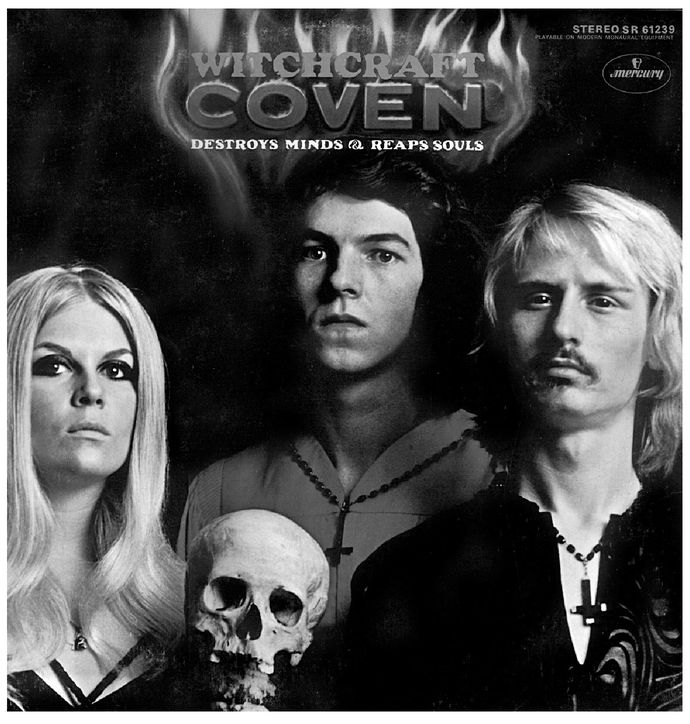

Coven are just as obscure, but deserve greater attention for their overtly diabolic album Witchcraft: Destroys Minds and Reaps Souls. Presented in a stunning gatefold sleeve with the possessed visages of the three band members on the front, the cover hints at a true Black Mass, showing a photo with a nude girl as the living altar. The packaging undoubtedly caused consternation for the promotional department of Mercury Records, the major label who released it, and the album quickly faded into obscurity. Today it fetches large sums from collectors, clearly due more to its bizarre impression than for any other reason. The songs themselves are standard end-of-the-’60s Rock, not far removed from Jefferson Airplane; the infusion of unabashed Satanism throughout the album’s lyrics and artwork makes up for its lack of strong musical impact. In addition to the normal tracks, the album closes with a thirteen minute “Satanic Mass.” The inside cover warns:

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Black Mass to be recorded, either in written words or in audio. It is as authentic as hundreds of hours of research in every known source can make it. We do not recommend its use by anyone who has not thoroughly studied Black Magic and is aware of the risks and dangers involved.

8

Coven included the attractive female lead singer Jinx as well as a man by the name of Oz Osbourne, who bore no relation to the British vocalist “Ozzy.” In an additional coincidental twist, the first track on the Coven album is titled “Black Sabbath.” The Witchcraft album was released a year or two before Sabbath’s eponymous debut in 1970, but the hidden links that exist between the two are up for speculation. Like their English counterparts in Black Widow, Coven devised a live show that puts many of the modern Satanic bands to shame. In a 1996 interview, former member Osbourne recounted the grandiose proceedings to Descent magazine as follows:

We did a lot of our album and other things as our stage show, intermixing the Black Mass, or Satanic Mass, as kind of a segue between the songs. Behind the stage we had an altar and on top of the altar we had what we called a Christian cross and we had one of our road people hanging on the Christian cross as Jesus, and he just kind of stayed there during the whole show. Our stage was lit with obviously a lot of reds, and we had candles and that kind of thing. Then we would do our whole album and other materials that all dealt with interesting stories of witchcraft. Of course we were costumed. ... right at the end of our set we did a Procol Harum song that was just appropriate, called “Walpurgis.” And right in the middle of it we break into the “Ave Maria.” At that point Jinx would do the benediction of the Black Mass and she’d recite the Latin bits and she would go, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law,” which is Crowley ... She’d say the Crowley bit then would hail Satan and would turn around and scream “Hail Satan!” at the cross and altar, at which point the guy (Jesus) would pull his arms off the cross, get down, invert the cross into the Satanic symbol, and would go dancing off the stage while the music was still playing.

9

After their outrageous debut, Coven recorded a few more major label albums, the diabolism drastically toning down with each succeeding release. Stories persisted for a time of a planned “Satanic Woodstock” in the early ’70s where Coven was to play as a prelude to an address by Anton LaVey, High Priest of the Church of Satan. This rumor is verified in Arthur Lyons’s book The Second Coming: Satanism in America (later revised and reissued as Satan Wants You). Lyons traveled with LaVey to Detroit, where the festival was due to take place on Halloween, only to find the show cancelled due to controversy. Coven did manage to perform their full Black Mass spectacle at a Detroit nightclub the next evening, which frightened the living hell of out an acid-tripping Timothy Leary in attendance. The band’s only widespread recognition came years later with the unexpected national hit single “One Tin Soldier,” which some (predictably) speculated was the result of their pact with the Prince of Darkness whom they had once so boldly acknowledged. Despite Coven’s obscurity, the Witchcraft album was striking enough to be discovered by some of the more important Satanic musicians in recent years, illustrating another link in the continuum of demonic Rock over the decades. King Diamond, the singer and driving force behind Mercyful Fate, one of the most important openly Satanic Metal bands of the ’80s, acknowledges he received dramatic influences from a Black Sabbath concert he attended as a kid in his native Denmark in 1971. He also tells of finding inspiration from Coven’s lead vocalist Jinx:

An amazing singer, her voice, her range... not that I stand up for the viewpoints on their

Witchcraft record, which was like good old Christian Satanism. But they had something about them that I liked...

10

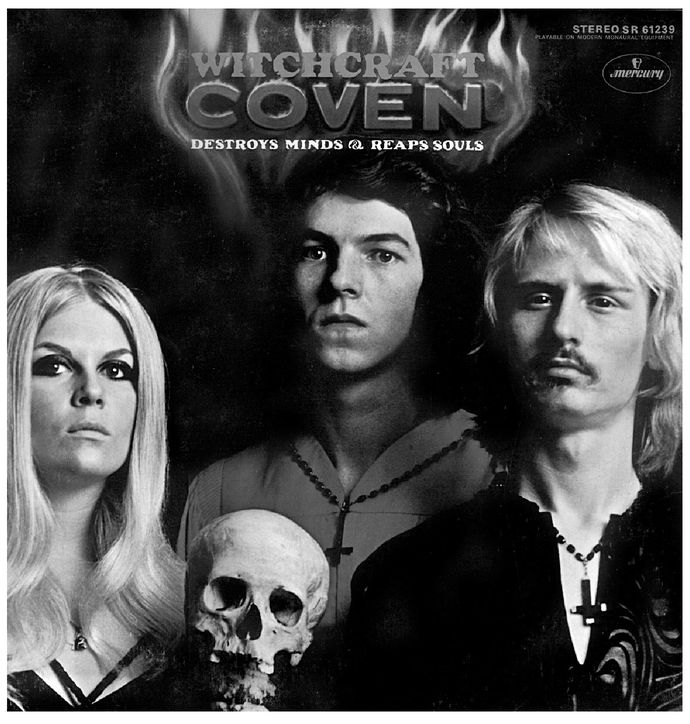

ENTER THE BLACK POPE

As integral to Satanic popular culture as any of the aforementioned music groups was Anton Szandor LaVey himself. Following years of observing the seamier folds of life as a carny, police photographer, burlesque organ accompanist, and occultist, LaVey made headlines when he founded the first official Church of Satan on the dark evening of Walpurgisnacht, April 30, 1966. The fundamentals of the Church were based not on shallow blasphemy, but opposition to herd mentality and dedication to a Nietzschean ethic of the anti-egalitarian development of man as a veritable god on earth, freed from the chains of Christian morality. LaVey’s Church was tailor-made for unending media attention, which soon made it a household word around the globe. In 1968 he released a Satanic Mass LP, which also broadcast a “Black Mass” from its grooves. Not centered on the medieval imagery found on the Coven album, it functioned instead as an exercise in the rejection of Christian doctrine. LaVey explains:

I don’t think it was originally released as propaganda, but rather to set the record straight as to what a Satanic Mass is, opposed to a Black Mass, the latter of course just an inversion of a Christian rite. It was also an opportunity to reach a certain element at that time. There was no such forum for performance art at that time. The recording was done live with different tracks—it was recorded as performed. But I guess you could say it turned out to be propaganda ... it was subsequently distributed by Lyle Stuart [the publisher] and Howard Hughes funded some of that. He was quite sympathetic to what we were doing.

11ANTON LAVEY

Looking back today on the relevance and influence of the

Satanic Mass, LaVey notes, “I can see and appreciate it more than I could for years. For awhile I thought of it just as a documentary, similar to the LPs that came out in the early ’70s like

The Occult Experience. But now I realize it was a first for the kind of visuals which you’re seeing all over today. It really was twenty years ahead of its time in many respects.”

12 Following the “mass” ceremony, the B-side of the album also contained a number of Satanic declarations by LaVey, recited over the strains of Wagner and other bombastic scores. These texts were gleanings from LaVey’s essays that would later form the framework of his infamous book the

Satanic Bible which appeared in 1969. The only openly Satanic manual of thought to be widely distributed to the masses, it is impossible to accurately gauge the impact LaVey’s book has had on society since its appearance almost thirty years ago. Readily obtainable, the book inevitably influenced the more prominent Rock musicians exploring themes of demonism and the occult in their personas, songs, and stage shows. In the heyday of such experimentation, a bizarre LP of entirely electronic synthesizer pieces devoted to the Devil even surfaced in 1971 on MCA Records, entitled

Black Mass Lucifer. By the end of the ’70s only a few of the major Metal acts were paying homage to sinister forces, and this was usually done superficially or with tongue in cheek, as on Sabbath albums like

We Sold Our Souls for Rock and Roll, and AC-DC’s

Highway to Hell. But it was LaVey’s

Satanic Bible that ensured the Devil a permanent place on hundreds of thousands of bookshelves the world over. With a decade of mainstream coverage for Satanism as a religion, and many of Hollywood’s rich and famous converting to the new creed, others would be quick to follow.

BLACK MASS LUCIFER LOGO

THE NEW WAVE OF BLASPHEMY

The most discernible roots of the modern wave of Black Metal arising in Norway and elsewhere in the beginning of the 1990s can be clearly seen in the pioneers ten years earlier—Venom, Mercyful Fate, and Bathory. In tracing this lineage we have already stepped onto subjective territory, and others would argue for the inclusion of Slayer, Hellhammer, and Sodom alongside the above triumvirate. These bands made their undeniable mark as well, and will be noted in the next chapter. But by dint of chronology and primary impact both in terms of music, appearance, and philosophy, our focus concentrates on the former three.

THE UNHOLY TRINITY: VENOM

Venom began in 1979–80 in Newcastle, England, the result of three Metal fans and musicians deciding to take things one step further than their contemporaries. Even their mortal names were not intimidating enough to reveal, thus Conrad Lant, Jeff Dunn, and Tony Bray respectively adopted the more evil-sounding noms de guerre of Cronos, Mantas, and Abaddon. Their music was to be as over-the-top as their stage names, with equally abnormal lyrical content. Their beginnings and influences go straight back to the earliest Heavy Metal bands such as Black Sabbath and Deep Purple, as Abaddon explains:

I was about nineteen. We were all into the older stuff—Judas Priest, Deep Purple, Motorhead, Black Sabbath. Mantas has always been a huge Kiss fan. We were drawing inspiration from these bands. We’d take some of the diabolical content of Black Sabbath and we’d mix it with some of the stage presence of Kiss, and with the originality of Deep Purple. That’s where we got Venom from. Venom was never meant to be a blacker Iron Maiden or anything, it was really based on older bands and what little pieces of those bands we wanted to emulate.

13

Venom took the heaviness and dark mysticism of these progenitors and gave it their own youthful punch-in-the-face to bring it up-to-date, as by this time the original Metal bands had settled into lavish lifestyles resulting from their success, losing most of the rawness that had once made them exciting. On close analysis, Venom was still playing fast Blues-based Rock, but with the primitive aggression which at that time was generally considered the property of the Punk bands. “Our music was born on the back of the Punk explosion in England,” states Abaddon, “if you drew back Venom’s influences I guess you’d find bands like Deep Purple and the Sex Pistols, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath.”

14 Thus it was not surprising that an array of their early fans were drawn from areas beyond the standard Metal crowd (many of whom considered Venom pointlessly offensive and untalented noise-makers). Abaddon remembers:

We played to skinheads and punks and hairies—everybody. Where some guy with long hair couldn’t come into a Punk gig, all of the sudden it was really cool to go to a Venom gig for anybody. That’s why the audience grew really quick and became very strong; they were always religiously behind Venom and they’ve always stayed the same.

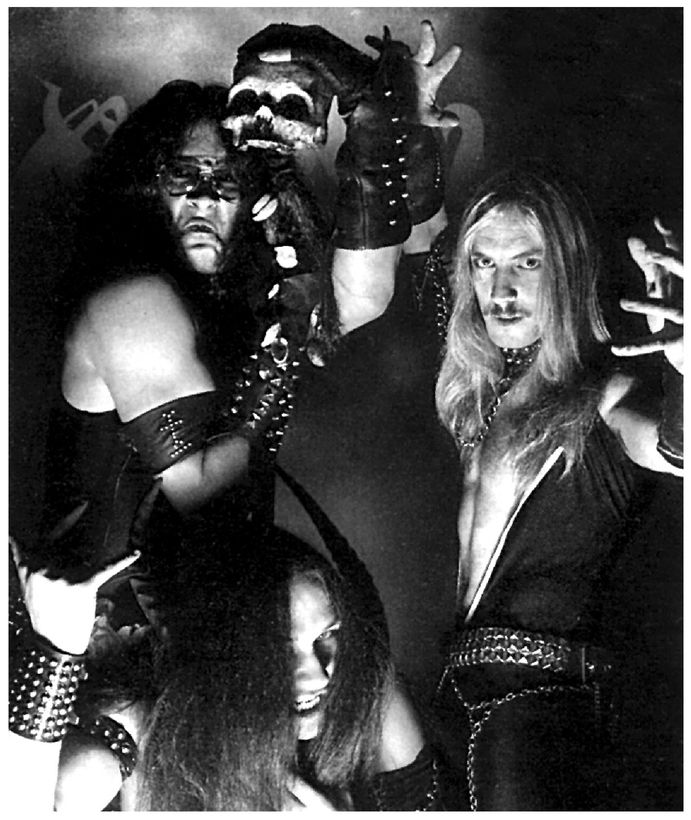

15VENOM

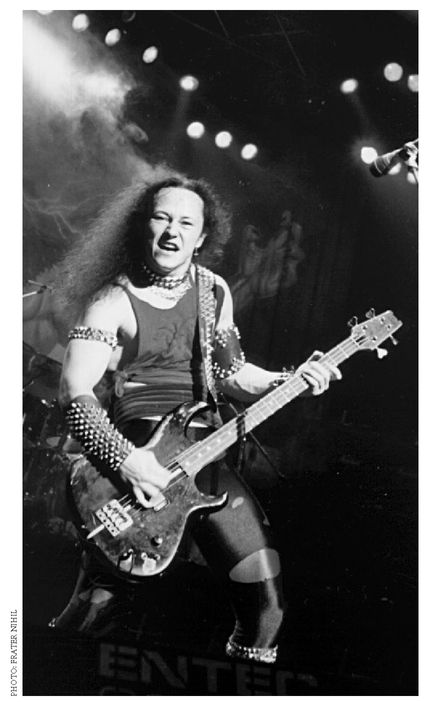

CRONOS OF VENOM

In America indeed a large percentage of Venom’s early fans came out of the nascent Hardcore Punk scene which was gathering momentum contemporaneously with the release of the band’s first singles. Old Venom standards like “Die Hard” echo the caustic, violent sound of early ’80s Black Flag more than any of the band’s fellow English Metal acts, although if you discount the low-fi recording, overly distorted guitars, and barked vocals of Cronos, one realizes Venom is arguably not much more than classic Sabbath warp-speeded to 78 rpm.

Besides pioneering a dirtier sound than any other extant Punk or Metal band in Europe, Venom’s notoriety was doubly assured with their elaborate endorsement of Satanism to a degree which would have caused wet dreams for medieval inquisitors. Given the level of blasphemy they made their trademark, it is not surprising the band could be embraced as panacea for the soul by kids brought up in stifling Christian environments, and looking for any possible way out. Whether or not Venom’s members really practiced such rites in private was altogether irrelevant for listeners who could revel in the statements found on their album sleeves:

We drink the vomit of the priest Make love with the dying whore We suck the blood of the beast And hold the key to death’s door16

Such polemics struck a chord with their fans, and the vintage Venom albums Welcome to Hell (1981), Black Metal (1982), and At War with Satan (1983) have gone on to sell hundreds of thousands of copies over the years. With the title of their second album, Black Metal, a future style of Satanic music had found a name. The record also carved in stone some of the genre’s essential features. Primary among these would be an open policy of violent opposition to Judeo-Christianity, endless blasphemy, and the abandonment of all subtlety in favor of grandiose theater which teetered over an abyss of kitsch and self-caricature. The magnitude of Venom’s overwrought image was tempered considerably by some of the songs which wound up on their early LPs. Despite the Satanic trappings, they were still a Rock band after all, and numbers like “Teacher’s Pet,” “Angel Dust,” and “Red Light Fever” are little more than shockingly low-brow paeans to sex, drugs, and cheap thrills.

MANTAS OF VENOM

Early interviews with the members of Venom make it clear they themselves were beer-swilling Rock and Rollers out to have a good time. The Satanism projected in their presentation and lyrics was primarily an image they stumbled upon, guaranteed to assure them attention and notoriety. There is no real philosophy behind it, beyond the juvenile rebellion of presenting anti-Christian blasphemy in the most lurid manner one’s imagination can muster. Abaddon’s reply to the question of whether he considers himself a Satanist is honest, but at the same time demonstrates it was probably never a real concern for him:

I certainly have in the past. I haven’t spent a lot time on any one religion for quite a few years. It’s something that I’m getting back towards, and I get a lot from people like LaVey. I’m a firm believer in all religions. Religion has become money now, and it’s a very dangerous area because people can become very persuasive. We’ve always tried to make Venom as powerful and as loud and unmissable as we possibly can, but without preaching to people. We’re very conscious about that. All the fans are called Legions and we are at their behest, but we don’t want to preach. It’s quite a difficult thing. We don’t want to be seen as some kind of organized religion whereby you have to buy the T-shirt or the album to keep funding the thing that is Venom. If you don’t want to listen to Venom anymore, so be it.

17

In a 1985

Kerrang! interview, Cronos was even more blunt: “Look, I don’t preach Satanism, occultism, witchcraft, or anything. Rock and Roll is basically entertainment and that’s as far as it goes.”

18 If one were to reduce Satanism simply down to the credo of “doing your own thing,” then Venom may be “Satanists”—but by that criterion the Beach Boys probably are as well. After

At War with Satan Venom diluted much of its image, and personnel changes wrought havoc on the integrity of their later recordings. Still, the band’s vintage albums had caught the ears of thousands of feisty kids, and their (fabricated) image as vehement desecrators of the holy set the stage for the next generation to carry the newly lit Black Metal torch forward.

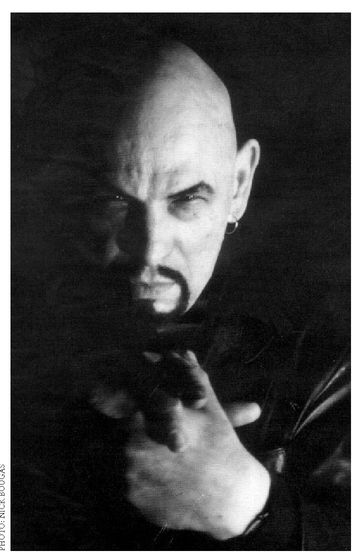

A MERCYFUL KING

The bands from the early 1980s who would have the most profound influence on the development of Black Metal as a genre have all on occasion acknowledged their familiarity with LaVey’s Satanic Bible, and in the case of King Diamond and his band Mercyful Fate, it served as powerful inspiration. After stumbling across it in an occult bookstore, Diamond recalls:

I read the book and thought, hey, this is the way I live my life—this is the way I feel inside! It’s not like it was a major religion or anything like that, it was a lifestyle that I could relate to 500%. And it’s just nice to see your own views and thoughts in words, in a book. It comforts you in some way. And that is how I felt. ... and you’ll see it reflected in our early lyrics with King Diamond and Mercyful Fate. I used the word Satan at that time, and it had a very specific meaning for me—not the one that other people had.

19

Drawing musical influences from the godfathers of Heavy Metal such as Sabbath and Deep Purple, combined with King Diamond’s trademark operatic vocals, Mercyful Fate debuted with an eponymous mini-LP in 1982 which featured the anthem “Nuns Have No Fun.” This was followed by two more advanced albums,

Melissa (1983) and

Don’t Break the Oath (1984), brimming with stories of magical rites, nightmarish fantasies of the consequences of broken pacts, and declarations of Satanic allegiance:

“If you say Heaven, I say a Castle of Lies / You say forgive him, I say revenge / My sweet Satan, You are the One.”20MERCYFUL FATE’S KING DIAMOND

Adding a cleverly conceived stage presence, King Diamond sang out such blasphemous provocations under a mask of theatrically sinister black-and-white face paint, his microphone lashed onto a cross fashioned of two human legbones. In many respects the records of Mercyful Fate would exert the same influence on their fans that groups such as Black Sabbath had commanded on Diamond’s own musical beginnings. Diamond received occasional tabloid attention and much criticism for his promotion of evil subjects through his music, but he was always willing to declare his personal dedication to the LaVeyan brand of Satanism. He points out that the outlandish and gruesome imagery in some of his lyrics was nothing to be taken seriously:

I make pretty sure that nobody can come and say, hey, you are trying to influence people into doing this or doing that, or you want to convert people and so on. No way. I raise a lot of questions, definitely. But I try not to give—in straight words—an answer of what I feel about it... You’ll never see me doing things like that. People have got to make up their own minds. And if people are not interested in getting anything deeper out of words on an album, that’s fine too. We are entertainers—we’re not priests. I have my way of life and of course that will influence my music and my lyrics. I put all my feelings into both.

21MERCYFUL FATE

Diamond represents one of the only performers of the ’80s Satanic Metal who was more than just a poseur using a devilish image for shock value. Between his openness about his personal commitments and the masked theater of his stage persona, his influence would be apparent when Black Metal was resuscitated with new blood in 1990–91. It’s difficult to imagine King Diamond causing anyone to commit atrocities in emulation of his down-to-earth philosophy. The required stimulus would come in the more overt blasphemies of bands who pushed the themes to further extremes, and provided a vastly more volatile cocktail for teenage fans to imbibe.

THUNDER GODS: BATHORY

The Swedish group Bathory, along with Venom, are torch bearers in the evolution of modern Black Metal. Bathory takes its name from the “Blood Countess” Erzebet Bathory, a Hungarian noblewoman in the 1700s put on trial for the murder of hundreds of young girls, in whose blood she alleged bathed to maintain her youthful beauty. It is highly probable that an early Venom number, “Countess Bathory” on the Black Metal album, may have provided the direct inspiration for the name, as Bathory owes much of its initial sound and look to the English founders of Black Metal. The driving force behind the group is a man who uses the stage name of Quorthon (although, in point of fact, Bathory have never in their career played a live concert before the public). He describes the band’s first efforts:

At that time I must have been 15, and I was helping a record company out with listening to new bands because there was some kind of Metal wave going on, I believe due to the “New Wave of British Heavy Metal.” At that time I found out they were going to put together a Metal compilation album with five or six Swedish bands, and I asked, “Please can you listen to my band, because we play a really exciting type of new Heavy Metal.” That was January, 1984.

BATHORY’S FIRST ALBUM

I never thought we’d be able to enter a studio again after that because we were really dirty sounding. But it turned out that 85-90% of all the fan mail that came to the record company from that record [the compilation was titled Scandinavian Metal Attack] was about our songs. So the guy from the record company called me up and said, “Hey, you really need to put your band together again and write some songs, because you have a full-length album to record this summer.”

BATHORY GO VIKING

I thought we’d be selling two or three thousand copies; that album is still selling like crazy nine years later. I’m still really amazed about it, especially since when it was recorded it cost me about two hundred dollars and was recorded in fifty-six hours in a twelve-track demo studio south of Stockholm. From then on we just recorded every album on more or less “borrowed time” because we didn’t really have any ambitions whatsoever, up until Important Records asked us to come over and do some kind of tour together with Celtic Frost and Destruction in the summer of ’86. While all this was happening I of course didn’t have a line-up together because, if you know anything about Swedish music at that time, the musicians were bound to look like the band Europe [an effeminate Hard Rock band popular in the mid-80s]! So when I’d drag a drummer down to my rehearsal place and play him the first record of Bathory, he’d go, “Oh no, oh no!” There just wasn’t any atmosphere or tradition for Death Metal at that time, as there is today. ... Everybody seems to think that I’m a megalomaniac with a big head or something, but it wasn’t really my fault—I should have been born in some place like San Francisco or London where I would have had a real easy time putting this band together.

22

AN EARLY BATHORY PROMO PHOTO

Bathory’s first three albums follow a similar mode of expression as Venom, though the music is made even more vicious by a potent arsenal of noisy effects and distortion. The hyperkinetic rhythm section blurs into a whirling maelstrom of frequencies—a perfect backdrop for the barked vocals of an undecipherable nature. Much of the explanation for this sound was simply the circumstances of recording an entire album in two-and-a-half days on only a few hundred dollars. The end result was more extreme than anything else being done in 1984 (save maybe for some of the more violent English Industrial “power electronics” bands like Whitehouse, Ramleh, and Sutcliffe Jugend) and made a huge impact on the underground Metal scene. In retrospect Quorthon says of Bathory’s first self-titled album, “If you listen to it today, it doesn’t make you tickled or frightened, but in those days it must have made a hell of an impression. Thinking back on how it was recorded, it’s amazing how big things can be made with small measures sometimes.”

23 The lyrics were centered on black magic and Satanism à la Venom, although funneled through a bit of Scandinavian innocence and teenage melodrama which made them come off as even more extreme in the end. Quorthon is very honest in his assessment of the Satanism on the early records:

Well, at the time it was very serious, because today, ten years later, I don’t think I know anything more about it than I did then. I’m not one inch deeper into it than I was at that time, but your mind was younger and more innocent and you tend to put more reality toward horror stories than there is really. Of course there was a huge interest and fascination, just because you are at the same time trying to rebel against the adult world, you want to show everybody that I’d rather turn to Satan than to Christ, by wearing all these crosses upside down and so forth. Initially the lyrics were not trying to put some message across or anything, they were just like horror stories and very innocent. But nevertheless at the time you thought that you were very serious, and of course you were not.

24

As Bathory matured over the course of their subsequent records,

The Return... (1985) and

Under the Sign of the Black Mark (1987)

, the music slowed down noticeably, songs became more elaborate, and the subject matter began to convey a degree of subtlety and ambiguity a far cry from the earliest singles. At this point came a remarkable shift of focus which, like their early primitivity, would also greatly influence the Black Metal scene of the future.

Blood Fire Death, Bathory’s fourth LP, hit record shops in 1988 and was eagerly grabbed by extreme Metal fans around the world. Instead of the B-grade horror cover art of the previous album, an entirely different image greeted them: a swarming, airborne army of enraged valkyries on black horses, spurred on by the Nordic god Thor, hammer held aloft in righteous defiance as a wolfskin-cloaked warrior drags a naked girl up from the scorched earth below. This remarkable romantic painting by Norwegian artist Peter Nicolai Arbo, depicting the infamous “Wild Hunt” or

Oskorei of Scandinavian and Teutonic folklore, was the ideal entryway into Bathory’s new sound which lay on the vinyl inside it. More accessible than the band’s previous noisefests, the new album was, nevertheless, just as brutal.

Blood Fire Death employed the same amount of raw aggression, but channeled it through orchestrated songs and understandable vocals, which were helped along by more realistic and thoughtful lyrics. The first track was an evocative instrumental, “Odens Ride Over Nordland,” which recreates the soundtrack of sorts to the cover art, with the father of the Norse heathen gods, Odin (also called Oden, Wotan, and other names, depending on the Germanic language) riding his eight-legged horse Sleipnir across the heavens. The Norse gods are again invoked on the final track of the record, the title song:

Children of all slaves / United, be proud / Rise out of darkness and pain A chariot of thunder and gold will come loud / And a warrior with thunder and rain With hair as white as snow / Hammer of steel / To set you free of your chains And to lead you all / Where horses run free / And the souls of your ancient ones reign.25

With Blood Fire Death Bathory had forsaken the childish and foreign Satanism of their original inspiration but uncovered something just as compelling and fertile—the heathen mythological legacy of their own forefathers. The tapping of ancestral archetypes would become a matter of primary importance for the generation of Black Metal to follow, and an essential component of the genre.

The same inspiration resurfaced intensely on the next release, 1990’s Hammerheart, with the songs written from a more personal point of view. The record is, to a deeper and more romantic degree than its predecessor, an attempt to seriously explore the mindset of a Viking Age practitioner of Ásatrú religion. Ásatrú, which translates to “loyalty to the Æsir [the pantheon of pre-Christian Nordic gods],” is the modern word for the revival and reconstruction of the religious beliefs of the Norse and Teutonic Northern Europeans. It is often accompanied by a strong hatred of Christianity, considered to be an alien religion forced on one’s ancestors under threat of death. Bathory was not the only Swedish band of the period to advocate a return to Ásatrú (the singer of the heavy biker-oriented Punk group the Leather Nun in fact led an Ásatrú organization for a time), but they would have the most impact with their actions.

On Hammerheart, Bathory’s music undergoes an epic restructuring. Most of the songs clock in at ten minutes apiece, the vocals are clearly sung and even surrounded by chanted choral backdrops. Richard Wagner is thanked in the credits. The cover art, a romantic oil painting titled “A Viking’s Last Journey,” depicts a Viking ship burial of a nobleman, where the corpse is pushed to sea in a longship, set alight by torches. Ironically it was not long after this that many a Norwegian Bathory fan would pick up real-life firebrands, and employ them in their own neo-Viking fantasy.

The final release in Bathory’s “Ásatrú trilogy” came with 1991’s Twilight of the Gods, which further emphasized the musical elements of European Classical composition. Lyrical themes were drawn from Nietzsche’s dire warnings about the spiritual malady afflicting contemporary mankind. Beside this came veiled references to the SS divisions of World War II Germany in the song “Under the Runes,” which Quorthon admits was a deliberate provocation:

I wrote it in a way so that it would create a little havoc. “Under the Runes” is, to begin with, just my way of saying that regardless if it’s in the sky, the land, or deep down in the oceans, we will fight for my father’s gods’ right to have a place in any form of discussion when we discuss Sweden...

We tend to think of ourselves as modern, down-to-earth Protestant Christians—healthy Christians. And we never talk about how Sweden was prior to that, more than 900 years ago, because we have a history of 2,000 years of being Ása-faithful, and just 970 years of Christianity. And if they don’t want to talk about it, I’m prepared to fight any kind of war by the great hail, under the runes, for my father’s gods. Because there are certain values, from those times, worth fighting for.

And in creating havoc, being able to talk about what the song is all about, I wrote it so that it would be able to be taken as a Second World War song. Because then I knew people would keep on picking out that lyric, and then I would keep having to answer questions about it, and would get the idea out there.

26This was not the first time Bathory trod onto questionable ground with symbolism. Hammerheart featured a sunwheel cross emblazoned on its back cover, an oft-used icon of radical right-wing organizations. Quorthon professes some naiveté in the matter, but it’s hard to believe he wasn’t aware of the full potency of such visual elements. As he explains:

In Sweden that’s also the symbol for archeology, but in Germany it means something completely different. And the original colors for the logo and titles were black, white, and red—the original German colors. I didn’t even think about it, but people went berserk, so we had to print them in gold.

27

Though not conscious of its influence, Bathory managed to create the blueprint for Scandinavian Black Metal in all its myriad facets: from frenzied cacophony to orchestrated, melodic bombast; reveling in excesses of medieval Devil worship to thoughtful explorations of ancient Viking heathenism; drawing inspiration from European traditions to deliberately flirting with the iconography of fascism and National Socialism. Bathory’s first six albums encapsulated the themes which would stir unprecedented eruptions from the youth of Scandinavia and beyond.

Bathory’s bizarre bloodline of demonic inheritance—and that of Black Metal itself—can be traced straight back through Venom, Mercyful Fate, and other darker-themed Metal bands of the early ’80s, to the Heavy doom-ridden sounds of Black Sabbath and the mystical Hard Rock of Led Zeppelin, to their bluesy antecedents the Rolling Stones, and all the way to a poor black guitarist from the American South who may have sold his soul to Satan in a lone act of desperation. An unlikely Black Metal pedigree, but there it stands, helped along the way by countless others who poured their own creative juices into an evolving witches’ brew.

Only a few years and a few more selective ingredients were needed to push the cauldron of Black Metal from the edge of the hearth and into the fire...