FEAR RUNS WILD IN THE VEINS OF THE WORLD

THE HATE TURNS THE SKIES JET BLACK.

DEATH IS ASSURED IN FUTURE PLANS

WHY LIVE IF THERE’S NOTHING THERE?

SPECTERS OF DOOM AWAIT THE MOMENT THE MALLET IS SURE AND PRECISE COVER THE CRYPTS OF ALL MANKIND WITH CLOVEN HOOFS BEGONE...

—SLAYER, “HARDENING OF THE ARTERIES,” 1985

12

DEATH METAL DIES, BLACK METAL ARRIVES

BLACK METAL IS A BASTARD CHILD, CONCEIVED FROM THE PROMISCUOUS intermingling of a number of evil seeds, with only the general formula of Heavy Metal as its fecund womb. Abaddon notes the reality of the situation when discussing how many of the Metal sub-genres of the ’80s and ’90s came in the wake of Venom’s outbursts:

I don’t think any band sets out to become an institution. A band sets out simply to fulfill different goals at different times in their career. ... We were interviewed once and somebody said, “Venom’s obviously not a Heavy Metal band. You don’t sound like Heavy Metal and you don’t look particularly Heavy Metal; you look like punks with long hair.” We said Venom

is Heavy Metal—it’s Black Metal, it’s Power Metal, it’s Speed Metal, it’s Death Metal. And all of these sub-genres had never been heard of before. All of the sudden one band is considered a Speed Metal band, one is considered a Death Metal band, and another is considered a Black Metal or a Power Metal band. What we meant is that Venom is

all of these things, and all of these genres could emanate from Venom. We didn’t mean for it to happen, but that’s how it turned out. A band like Pantera have nothing in common with a Scandinavian band, or a band from England like Cradle of Filth—they don’t sound like them. But when you draw back to where their all influences come from, you find Venom.

2By the closing years of the ’80s, cutting-edge Metal groups had absorbed influences from both the bombastic “New Wave of British Metal,” with ultra-masculine bands like Saxon and Judas Priest (the latter so much so they often crossed over the line of homoeroticism, with singer Rob Halford’s leatherman get-ups), and the burgeoning Hardcore scene, with its lack of pretentiousness and gritty depictions of reality. The gnarlier second generation of Punk, Hardcore mirrored the same angst of the lost generation of American youth as did Metal; both thrived and cross-pollinated in the sprawling no man’s lands of suburbia. Punk’s do-it-yourself ethos carried over into everything and increasing numbers of kids formed their own bands, pressed their own albums, and organized concerts. Hardcore began to merge with elements of Heavy Metal and vice versa. Boundaries blurred and—as in the early days of Venom—kids from both scenes liked the same bands, attended the same shows, and voiced the same simple slogans of teenage turmoil and rebellion.

UNITED SATANIC AMERICA

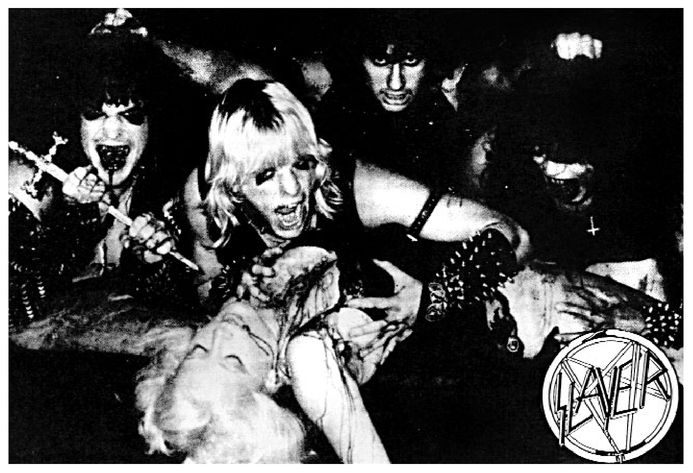

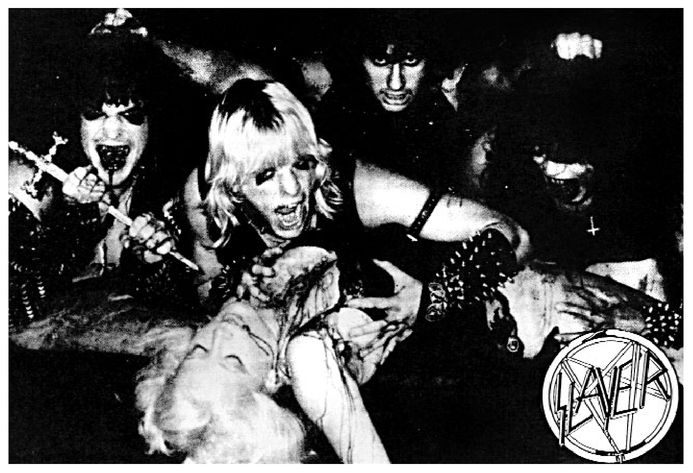

Overt expressions of Satanism remained buried deep in the Metal underground, and Venom never reached the same visibility in the U.S. they had achieved in England. The closest American parallel to Venom was L.A.’s Slayer, with their odes to bloody sacrifices and moonlit rituals on the early records Show No Mercy (1983), Haunting the Chapel (1984), and Hell Awaits (1985). Bands from the States never seemed to achieve quite the unadulterated level of blasphemy wielded by the British founders of Black Metal, but they did their best. Slayer penned endless songs about Satan and black magic, but interspersed these with vague attempts to comment on the horrors of warfare and other social ills. After some initial promo photos dressed up in spikes, leather, and makeup, feigning the bloody sacrifice of a blond female, the band opted for a more realistic image of beer-drinking everyday Metalheads.

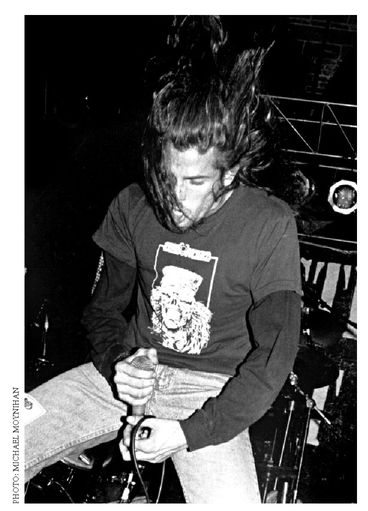

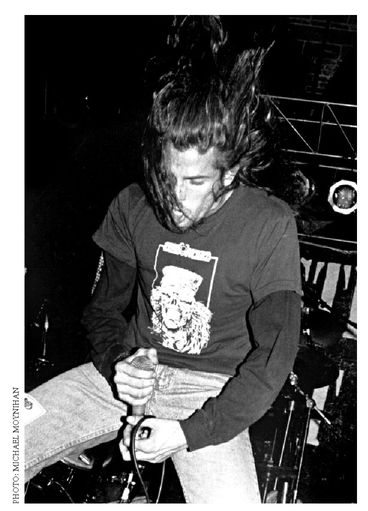

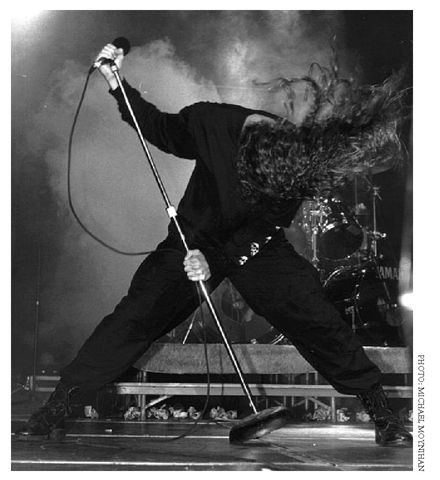

SLAYER ONSTAGE

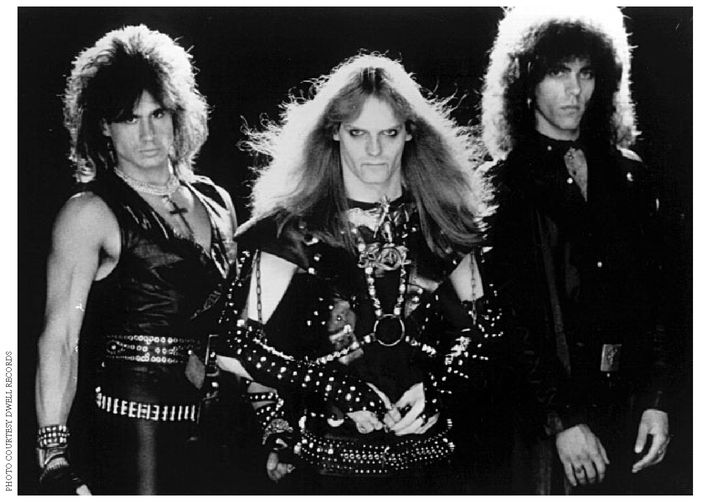

While most of the harder American Metal bands of the period stuck to less ornery lyrical themes, Slayer were not the only ones dabbling in diabolism. Another California band, Possessed, released its Seven Churches album in 1985, destined to be a influential slab of proto-Black Metal, and others waited in the wings to emerge. Even Mötley Crüe, later to devolve into Glam Rock sissies, began with a punkified debut and followed it up with Shout at the Devil, bringing a watered-down taste of the demonic to hundreds of thousands of impressionable suburban kids.

Equally important are the Misfits, Glenn Danzig’s Punk band from the early ’80s. They never sang of political problems (like the rest of their Punk and Hardcore peers) but rather a realm of B-grade horror films and space aliens. Beginning with a campy image of ghoulish makeup and “Devil locks” (a pointed clump of hair hanging down in front of their faces), the Misfits mutated into Samhain, injected more Metal into their sound, and sang pagan hymns to dark forces in nature. By 1988 the group had changed names again, to simply Danzig. They continue to this day, pumping out impious Blues-based Metal and walking much the same tightrope of spiritual and moral ambivalence as Black Sabbath did two decades ago.

SOUNDLY THRASHED

The late ’80s saw the brief ascendency of Thrash Metal, exemplified by bands like Anthrax, M.O.D., Metallica, and even the more extreme Slayer. In Europe, the German groups Kreator and Sodom left a strong mark, along with Swiss ensemble Celtic Frost, who started out as the seminal outfit Hellhammer. Sodom toyed with Satanic themes on their first few albums, and band members adopted pseudonyms of “Angelripper,” “Witchhunter,” and “Grave Violator”—the last of these bearing an ominous ring in light of the real-life activities Black Metalers would partake in a few years later. Hellhammer/Celtic Frost flirted with darker occult subjects for lyrical fodder, but eventually turned into something resembling a metalized Art Rock band. Like any style hyped incessantly by the music industry, Thrash Metal’s days were ultimately numbered. The genre became too big for its own good and major labels scrambled to sign Thrash bands, who promptly cleaned up their sound or lost their original focus in self-indulgent demonstrations of technical ability.

POSSESSED SEVEN CHURCHES

Peter Steele of gothic Metal band Type O Negative (and former frontman of the late ’80s “neo-barbarian” Speed Metal act Carnivore) accurately characterizes Thrash Metal as a form of “urban blight music,” a palefaced cousin of Rap.

3 His remark is astute, and it wasn’t long before Thrash bands like Anthrax actually began collaborating with Rappers and incorporating elements of Hip Hop into their songs. The less compromising underground watched such developments with dismay, and eagerly awaited for its phoenix to arise from the ashes of the now dead Thrash genre.

Innovations in the louder forms of music have almost always come at the hands of the fans—fans who pick up instruments of their own, determined to do one better over their mentors, or disgusted with seeing their favorite music swamped in the wake of commercial sell-outs and corporate record labels meddling in the affairs of the underground. Speaking about the longevity of extreme Metal, Abaddon of Venom observes, “This kind of music always fractures, but the most important thing is that it always has a lot of passion in it, from the fans, which keeps it together. It’s the power of the fan base that will always keep it there.”

4CELTIC FROST

DEATH THROES

Concurrently emerging in both the U.S. and Europe, Death Metal was the antidote the underground had awaited, reintroducing a sense of immediacy and danger otherwise lost after the early demise of Thrash. Death Metal took the speed of both Hardcore and Thrash to build its skeleton, and fleshed this out with churning, down-tuned guitars and a growling style of singing which provided a dramatic antithesis to the falsettos and high-pitched lead vocals dominating mainstream Metal at the time. Death Metal’s subject matter was not far off from that of the Misfits, but instead of B-grade ’50s horror, one now found the Z-grade slasher movie violence of the ’70s and ’80s served up in endless rotation. Songs detailing infinite varieties of murder, torture, rape, and dismemberment were spewed out from the growing army of Death Metal acts around the globe. The related genre of Grindcore, more heavily indebted to the politics of English anarchist and “peace Punk” pioneers like Crass and Rudimentary Peni, produced its own massively popular groups Extreme Noise Terror, Napalm Death, and Carcass. The latter are noteworthy for their graphically nauseating cover art on records like Symphonies of Sickness—collaged photographs of butchered meat and human autopsy photos, accompanied by lyrics drawn from textbooks on medical pathology.

EARLY SLAYER PROMO PHOTO

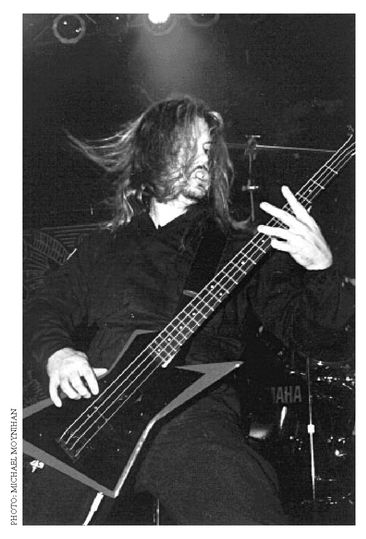

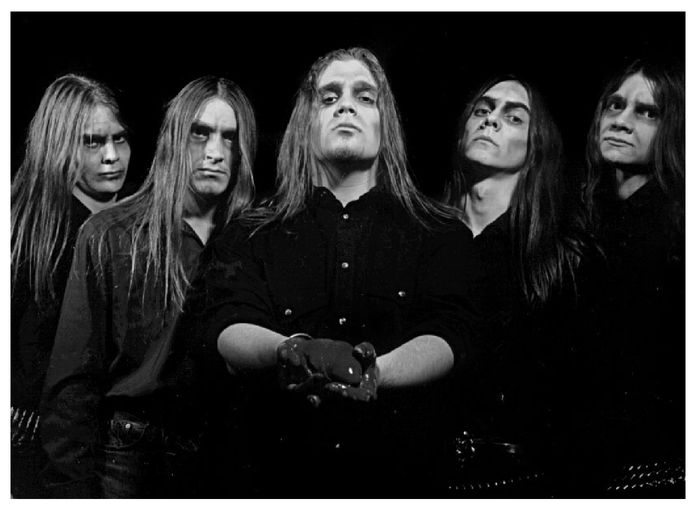

MORBID ANGEL

The two world capitals of Death Metal were the unlikely locations of Tampa, Florida and Stockholm, Sweden. From these extremes of fire and ice, the genre produced its most influential acts: Entombed, Hypocrisy, Dismember, and Unleashed from Sweden; Morbid Angel, Death, Obituary, and Deicide from the swampy netherworld of Florida. Other areas of the States also spat out bands of notoriety—misogynist gore fans Cannibal Corpse from upstate New York, equally rude and savage Autopsy from California—but the two aforementioned cities had specific recording studios and record producers which indelibly shaped the sonic boundaries of the genre. Death Metal eschewed the theatrics of its musical predecessors, instead opting for a “dude-next-door” look which remained unchanged on stage or off. Ripped jeans or sweatpants, high-top sneakers and plain leather jackets became the Death Metal uniform, and band members were assured of never being recognized by fans on the street since they looked no different than a thousand other sallow-faced urban hoods.

CANNIBAL CORPSE

A few exceptions came from the overtly Satanic bands who made up a small segment of Death Metal overall. The flamboyant singer of Deicide, Glen Benton, ceremoniously branded an upside-down cross into his forehead, threw bloody entrails into concert crowds, and sported homemade armor on stage; fellow Floridians Morbid Angel began donning paramilitary clothes for their live appearances, courting a neo-fascist demeanor, and reinforcing it with inopportune and illiberal comments in magazine interviews. For the most part however, the genre rested on its laurels of unbridled sonic brutality and lyrical glorification of all things morbid and decaying.

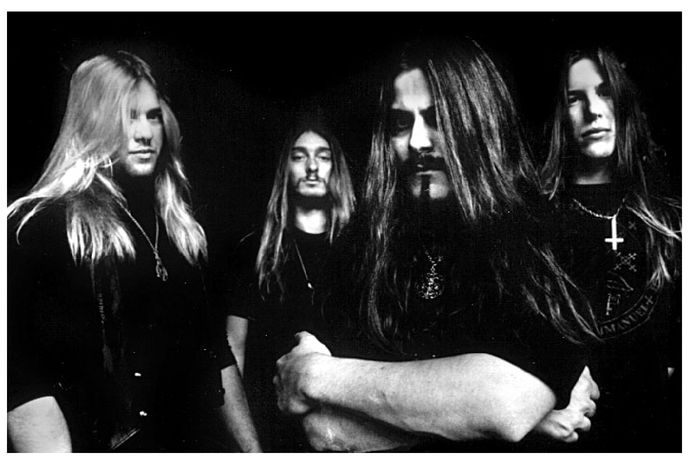

DISMEMBER

As Death Metal gained momentum, only a few bands from the Thrash days remained who commanded any respect from the younger generation. Slayer continued to be revered as godfathers of the scene, and in turn the band kept fans interested as they shifted subject matter from juvenile Satanism to an open-ended fascination with violence in general. Serial killers, genocide, religious persecution, and other apocalyptic topics all became grist for Slayer’s lyrical mill. Additionally they often employed the long-standing Metal tradition of invoking specters of Nazism and fascism in their lyrics and packaging. Slayer’s fans were dubbed the “Slaytanic Wehrmacht,” Nazi eagles were incorporated into the band’s logo, songs were penned about Josef “Angel of Death” Mengele, and Jeff Hanneman adorned his guitar with photos of concentration camp corpses. They gained an added following from neo-Nazi skinheads as as a result, but it would be difficult to take much of this seriously upon closer examination of the group—despite his last name, there is nothing remotely “Aryan” about lead singer Tom Araya, who in fact comes from a Hispanic South American background.

OBITUARY

DEICIDE

VIKING DEATH SQUADS

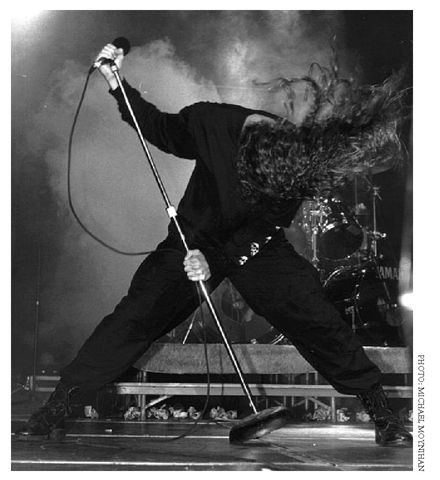

One Scandinavian Death Metal group in particular set a precedent for certain of the Black Metal bands to appear some years later. This was Stockholm’s Unleashed, who emerged after the breakup of early Swedish Death Metal group Nihilist. Unleashed never concerned themselves with the gory interests of their fellow bands, but instead made a similar discovery to Bathory and drew creative stimulus from the pre-Christian heathenism of their native Sweden.

From their first CD, Where No Evil Dwells, to the present, Unleashed have dedicated a significant number of their songs to themes drawn from the Viking Age and the old Norse religion. Their live concerts appear no different at first from a typical Death Metal show, until lead singer and bassist Johnny Hedlund starts making fervent declarations on the necessity of destroying the Christian religion of weakness and exhortations that “self preservation is the highest law!” This is certainly not the usual banter of a Metal band between songs, but they are sentiments that would be taken up by prominent Black Metalers soon enough. The band members proudly wear amulets of Mjöllnir, the Hammer of Thor, and at a certain point in every show Hedlund leaves the stage, to return seconds later clutching a huge Viking drinking horn filled with ale (or on special occasions, mead, the traditional sacred honey wine of ancient Europe). He will then dedicate a song, such as “Into Glory Ride,” to his Viking ancestors, drink from the horn and pour some of the libation onto fans in front of the stage. By incorporating such elements of tradition into their performances, Unleashed tap into the same atavistic well of energy which serves as a focal point for many of the most significant Black Metal bands.

Unleashed are also noteworthy as one of a small handful of Death Metal acts who have managed to survive the demise of the genre they themselves forged. Between 1989–93 Death Metal had become immensely popular worldwide, with bands drawing crowds in the thousands on an average night. The underground had been again pushed above the surface into commercial daylight, and it would—in typical fashion—react with a vengeance. As greedy record labels tried to cash in on the Death Metal trend by signing up untalented bands and releasing an endless stream of mediocre and remarkably unoriginal albums, the market was quickly swamped in a morass of interchangeable sludge. The irritated denizens of the underground began fomenting a new progeny they hoped would prove resistant to all attempts at co-option and dilution.

UNLEASHED

THOR’S HAMMER, MJÖLLNIR

In Norway, bleak clouds on the horizon brought with them cheerless portents of a storm to come. Sweden’s Death Metal underground had for years been in the world spotlight; it was considered the forefront of one of the most extreme varieties of music yet conceived. Norway also had its share of Death Metal bands, with names like Mayhem, Old Funeral, and Darkthrone. The leaders of the Norwegian scene realized—wisely—that in order to grab the attention of minds and souls they would need to willfully take things one step further. The fanciful violence and bloodlust of Death Metal wasn’t anything in itself—it must be made real, and become a means to an end, if it was to hold greater purpose. Otherwise it was nothing more than the audio equivalent of a comic book for kids to aimlessly gloat over. Venom had set an example with their exaggerated blasphemy, and had pointed out organized religion as a worthy target for assault. Raised amidst a complacent acceptance of Christianity as something inherently good, surrounded by an oppressive and numbing social democracy which dominated Norwegian political life, these youths would proudly adopt Black Metal as their own. Picking up where Bathory and Venom had left off, they injected their efforts with a grim seriousness the likes of which even the extreme Metal underground had never dreamt possible. The mistakes of Death and Thrash Metal would not be repeated. No, this would be something else entirely—something so pure and unsparingly severe it would sear a mark in the history books forever.