THAT FIRE

WHICH NEVER BURNS OUT

WHICH YET BURNS LOW

WHICH FLICKERS OUT

YET THERE REMAINS ALWAYS BENEATH THE ASHES EMBERS WHICH SMOULDER AND WAIT FOR ONE TO BRING DRY TWIGS AND WOOD

RED-HOT EMBERS DREAMING OF BECOMING A FIZZLING CRACKLING FIRE ONCE MORE

AND SUCH IS THE FIRE BURNING WITHIN OURSELVES.

—A LYRIC BY NORWEGIAN AUTHOR TOR ÅGE BRINGSVÆRD, PARAPHRASED AND RE-INTERPRETED BY VARG VIKERNES

16

ASHES

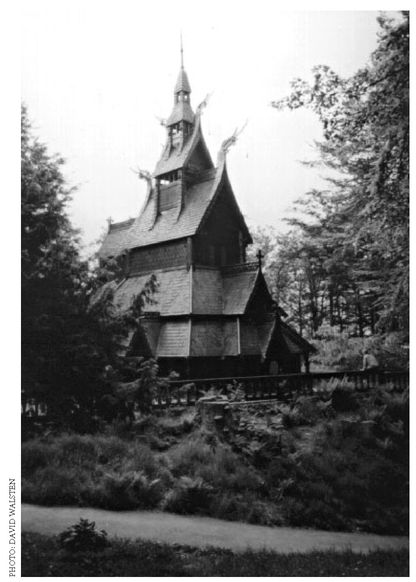

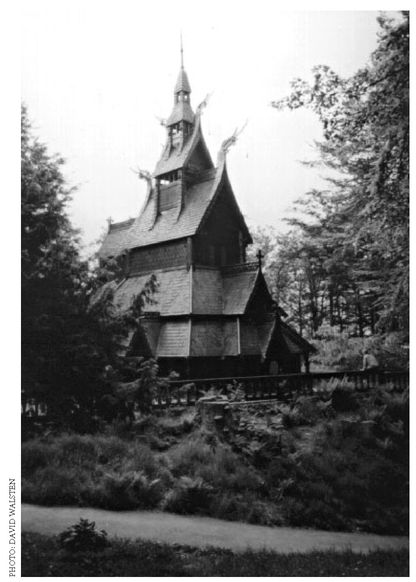

ONE OF NORWAY’S GREATEST HISTORICAL TREASURES IS THE STAVE CHURCH. These unique wooden congregation houses were built soon after the arrival of Christianity in Scandinavia around 1000 C.E. They continued to be erected up until the end of the Black Death, the bubonic plague which swept through medieval Europe in the 1300s. The name stave church is derived from the manner of their construction, which utilizes a strong post (stav in Norwegian) in the four corners of the main room.

The exterior of a stave church is commanding, often distinguished by gabled roofs and windows, with these smaller configurations leading to a sharp steeple. Entirely fashioned of wood, sometimes darkened or tinted blue-black from pitch, the more elaborate stave churches also bear intricate carved portals in ringarike-style Nordic interlace and interior motifs displaying remnants of heathen iconography. A dramatic example is a one-eyed carved head at Hegge and its vivid echoes of Odin in a state of ecstasy.

Sheathed in scaled, reptilian wood shingles, stylized dragon heads often rear up from the upper gable-points of the churches, adding to the foreboding effect. The external aura of the more elaborate stave churches conveys an impression of part wooden cathedral, part haunted house. Although not entirely exclusive to Norway (two less distinctive examples exist in Sweden and England), the stave church has become synonymous with that country. As many as 1,200 stave churches may have existed in the early Middle Ages; only thirty-two original examples survived in the second half of this century. That total has since been revised to thirty-one.

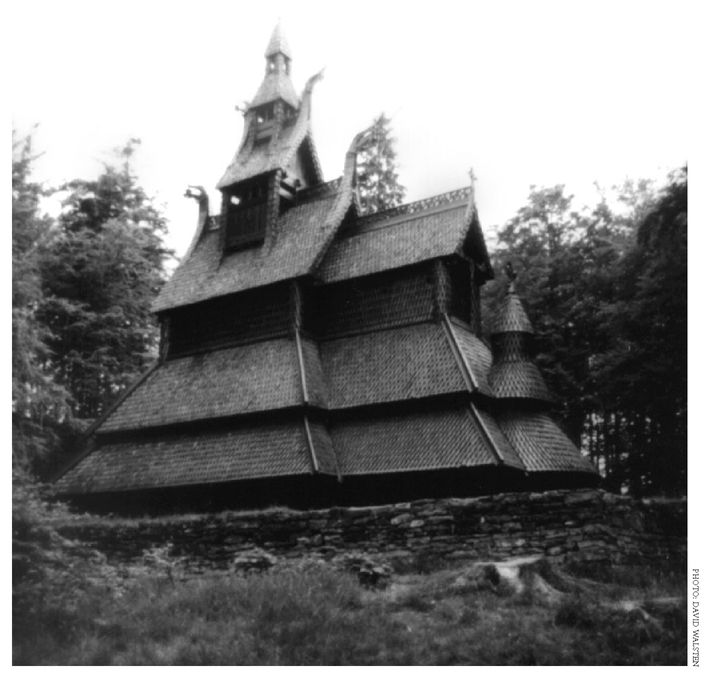

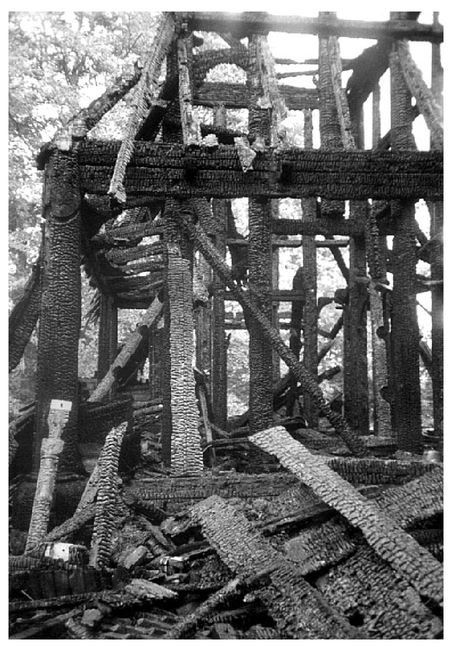

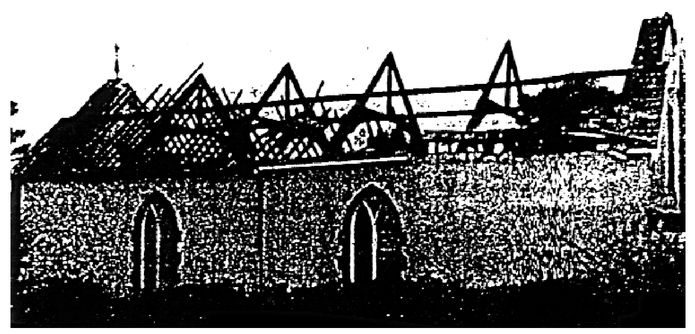

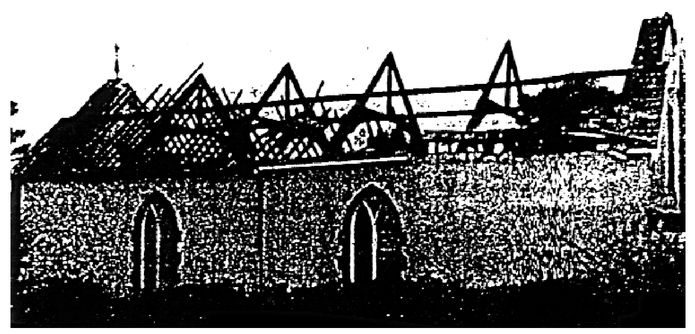

Before its day of judgement by fire in June, 1992, Fantoft arguably possessed the most ominous visage of any extant stave church. Dating from the twelfth century, it originally stood at Fortun, near the Luster Fjord in Central Norway. Like a number of stave churches, it also contained old runic inscriptions. At the close of the 1800s it was scheduled to be demolished to make room for a new burial ground. Unlike like many other stave churches that were destroyed during this period (before the realization of their great historical and cultural value), the church was saved when it was dismantled and moved to Fantoft, five miles south of Bergen on the west coast of Norway.

The groundplan of the building was slightly altered at the time of its reconstruction in 1883, and the entire exterior renewed. The church sat on a thickly wooded hilltop, where according to David Walsten, author of

Stave Churches of the World, “The trees were so dense that from some vantage points the church could not be seen until one was nearly upon it.”

2 The wooden construction of the traditional stave churches has always made them vulnerable to destruction by causes natural and unnatural, and the obscured location of Fantoft made the work of an arsonist even easier. Thus, early in the morning on the 6th of June, 1992, it was fatally torched, and while Vikernes is strongly suspected as the culprit, no conviction has ever been made in the crime.

FANTOFT IN 1990

News of the destruction of one of Norway’s cultural landmarks made national headlines. It would not be long before other churches began to ignite in nighttime blazes. On August 1st of the same year the Revheim Church in southern Norway was torched; twenty days later the Holmenkollen Chapel in Oslo also erupted in flames. On September 1st the Ormøya Church caught fire, and on the 13th of that month Skjold Church likewise. In October the Hauketo Church burned with the others. After a short pause of a few months’ time, Åsane Church in Bergen was consumed in flames, and the Sarpsborg Church was destroyed only two days later. In battling the blaze at Sarpsborg a member of the fire department was killed in the line of duty. Some would later consider this death the responsibility of the Black Circle.

FANTOFT

Beginning with a small, ineffectual fire at Storetveit Church in the month preceding the Fantoft blaze, there have since been a total of at least forty-five to sixty church fires, near-fires, and attempted arson attacks in Norway. Roughly a third have a documented connection to the Black Metal scene, according to Sjur Helseth, head of the Technical Department of the Directorate for Cultural Heritage. The authorities are reluctant to discuss the details of many of these incidents, fearing that undue attention may literally spark other firebugs or copycats to join the assault which Vikernes and his associates began in 1992.

PHOTO OF FANTOFT ALLEGEDLY TAKEN BY VIKERNES HIMSELF SHORTLY AFTER THE ARSON

Church fires themselves are not a wholly new phenomenon. On average, one or two churches have burned down per year in Norway in the past, most due to natural occurrences such as lightning strikes. Fire security at churches has been notoriously bad, and faulty electrical wiring can therefore also account for many of these fires.

However, there have also been cases of arson in the past. Churches are prime targets for pyromaniacs, and prior to 1992 there have been nine instances in Norway since World War II where churches have been deliberately set alight, for various reasons. Since pyromaniacs generally prefer uninhabited buildings, not really wanting to harm anyone, churches are ideal since they are usually situated away from residences—an added advantage to this being that it is easy to carry out the deed unnoticed. Finally, churches make very attractive fires, as the spire will cause flames to leap dramatically into the sky, creating a rather spectacular sight.

According to the law enforcement manual

Fire and Arson Investigation, “Arson as a crime predates the written history of common law,” and they note it “has always been regarded by the law as a heinous and most aggravated offense. It endangers human life and the security of habitations. It evidences a moral recklessness and depravity in the perpetrator.”

3 This attitude is certainly present in Northern Europe, and arson is specifically mentioned in the oldest extant Norse codes of law. In eleventh-century England, arson was a crime punishable by death. Later, during the reign of King Henry II, a person convicted of arson would be exiled from the community after they had suffered the amputation of one hand and one foot.

FIRE IN THE MIND’S EYE

Arson often afflicts a community due to the presence of a pyromaniac or pathological firesetter. These individuals have a psychological—rather than monetary—impulse behind the acts of arson they commit, and this often drives them to repeat the crime until caught. It is difficult to generalize about pyromania, and casebooks on the subject categorize different types of pyromaniacs according to their apparent motives: jealousy, paranoia, revenge, suicidal urges, and so forth.

On top of this, fire—especially in its destructive aspect—is a source of instinctual fascination for human beings in general. The 1951 study Pathological Firesetting by Lewis and Yarnell remarks:

Religion is only one outlet in which man indulges his hereditary fascination for fire carried in the racial unconscious, according to Jung. There are more practical methods of utilization. Everyone vicariously enjoys witnessing a devastating fire, and its appeal is sufficiently elemental to surmount intellectual and cultural differences. Adolescent boys out looking for excitement like a good fire. Angry mobs derive pleasure from burning the victims’ property; revolutionaries burn their oppressors’ estates; and warring men find in fire their greatest outlet for these destructive tendencies. In fact, some aviators describe with ecstatic fervor the joy and satisfaction they derive from watching the countryside burst into flames from their bombings; of course here is a reaction of justified revenge, but it still satisfies an instinctive urge.

4FROGN CHURCH BURNED

In reviewing the case literature, basic parallels can be found between the recent Scandinavian church-burners and certain classes of pyromaniacs, although the actions of the former are to a large degree unprecedented. In general they appear to fit into the classification of pyromaniacs motivated by “revenge.” The common viewpoint shared by Vikernes and others convicted of burning Norwegian churches is that their crimes were a form of justified retaliation against Christianity.

Lewis and Yarnell’s study of American arsonists found that among 457 cases of “revenge-spite firesetters,” churches were only the objects of attack in ten instances. In their overview of this classification of cases they write:

The conflagration is the most spectacular feature of revenge-motivated incendiarism. The firesetters are usually colorless figures who remain in the background. A woman is rarely directly involved ... Theirs is a deep-seated grievance, and literal revenge is desired. Hence their firesetting is not confined to gestures or playful attempts, but is intended to become destructive. Inflammable agents may be used.

Revenge is the strongest and most durable of all possible motives for firesetting, and revenge fires are set by offenders of any age, though the greatest incidence occurs in the 16–20 year old group. Adolescents will work as a group in setting this type of fire ... but the usual fire is made by a solitary individual.

5

In the discussion of “Boys Over 16 Who Make Fires in Groups,” similarities are evident with the dynamics of the Black Circle and its loosely-knit coterie with common interests, inspired and incited by a few of the more charismatic individuals within it. In forty cases of group arson activity studied:

The majority of these were 17–18 year old boys, most of whom worked in pairs, and where more were included, we find that the extra members were chiefly “hangers-on” and were usually not indicted or given a suspended sentence. In some cases, a large group of inadequate boys were completely under the influence of a leader.

6

One should bear in mind, however, that the same scenario is probably true of any juvenile group engaging in anti-social behavior or crime.

None but a few of the offenders in Lewis and Yarnell’s book mention burning down a church for ideological reasons. One of them states, “I can’t tell you why I [set fires], I just do. I didn’t pick on Catholic churches because I hated the Catholics. They were just easy places to get into.”

7 However, in a later state hospital examination it was determined this 17-year-old had possibly chosen the specific churches as a symbolic gesture against his estranged, Catholic father.

“Pyromaniac” is a classification which technically denotes someone who set fires for no other ostensible reason than some kind of sensual satisfaction. One intriguing case in Pathological Firesetting describes the actions and sentiments of a 20-year-old pyromaniac who set fire to a church where he had served as an usher during his youth:

After the morning service he unlocked a basement window, through which he entered the church that evening. The first match he struck went out—“It gave me a sensation when it went out. Something told me to continue and light the second match and I did. I couldn’t think of anything that would happen. As I entered the dark room it gave me a great thrill. It was so magnificently beautiful there and I thought it would be great to be more beautiful and magnificent still and I thought if the fire was set, no harm would be done and the building would probably be more magnificent than ever. As I continued on, it seems as though in every move I made there was more pleasure out of it. I felt a different person after I set the fire.”

8

The man later added: “I felt a double personality when I went into the choir room. I was filled with great enjoyment. I thought such a beautiful edifice should be destroyed. It should be destroyed to be created into a thing even more beautiful.”

9While there are slight similarities between some of these comments and the sentiments of Norwegian Black Metal church burners who viewed church fires as aesthetically beautiful, it would be inaccurate to lump them in the same category. True pyromaniacs tend to have a sexual impulse behind their action, according to psychologist Wilhelm Stekel, whose

Peculiarities of Behavior covers the affliction in detail. He believes “awakening and ungratified sexuality impels the individual to seek a symbolic solution of his conflict between instinct and reality,” resulting in pyromania in extreme cases.

10 Stekel further writes:

But in the case of the pyromaniac a second determinant [beyond sexual impulse] is also involved—revenge. Arson is an act of hatred. It is the expression of a destructive tendency. Love is creative, hatred destroys. But the question remains: against who is the hatred directed? Is it directed against the employers, or against the owners of the property set on fire? This should be accurately ascertained in every instance. Certain arsons have the immediate persons for objective, they are expressions of revenge for unrequited love, other deeds of this character aim at the pyromaniac’s own family, the parents, etc. They shall see to what their lack of heart has led. They are responsible for everything!

11

In the case of Varg Vikernes, he has often stated that he holds the Christian church responsible for destroying everything that was once beautiful in what he considers Norway’s true culture—that of the heathen age. He refers to the wave of arsons as an organic, instinctual uprising or revolution against the alien shackles of Christianity, and feels his music project Burzum to be a weapon in encouraging such outbursts. Curiously, he has also declared that Burzum is “a dream without holds in reality. It’s to stimulate the fantasy of mortals—to make them dream.”

12 In light of such beliefs proclaimed by Vikernes, one of Stekel’s remarks becomes intriguing:

We must also bear in mind that the pyromaniacs, as a rule ... attach considerable significance to their dreams and such individuals easily transpose into the impulse to set fire any impulsion to an asocial deed which may oppress them. What they hear is the voice of their own blood, transposed into a voice calling from within.

13

Stekel allocates some of his study to pyromania with overtones of sadism or cruelty. While Vikernes and the others apprehended for setting church fires have given reasons other than mere cruelty as a motive, none of them have expressed any degree of remorse for the suffering they caused in the lives of priests and churchgoers, or the painful impact on the surrounding communities. At the time of his first arrest in relation to any of the fires, Vikernes did make a number of extremely sadistic comments to newspapers and magazines which reflected the initial Norwegian Black Metal preoccupations with spreading “evil” and pain. When discussing the findings of fellow psychologist Iwan Bloch, Stekel summarizes:

Bloch in his endeavor to explain the pyromaniac tendency, has recourse to the assumption of a sadistic impulse and of a sexually toned destructive tendency. He points out that red is a color which plays a tremendous role in our

vita sexualis. The thought or sight of dark red flames exerts a sexually exhilarating influence, similar to the sight of the reddened body parts during flagellation, or of the flowing blood in sadistic indulgences.

14PRO-GRISHNACKH FLYER

Even while acknowledging that violent or criminal sexual drives may be an important factor in pyromania, as a psychologist Stekel approaches the issue of the crime quite differently than would a police officer or fire-man. His attitude toward the arsonist is a far cry from the days of the courts severing hands or feet, and ordering excommunication. Speaking of a pyromaniac, Stekel asks:

Is he a criminal? Is his arson a crime deserving punishment? My reply to both questions is a decided negative. Anyone who has read through the whole account must understand that the act was symbolic, there was no criminal motive behind it. It is desirable that similar cases be subjected to careful analytic investigation. Then it will be seen that many of these crimes are but the offshoots of faulty training and morbid environment.

15

The youths involved in the Norwegian Black Metal scene had certainly immersed themselves in a morbid environment. There is no evidence that Vikernes or the others felt any “sexually exhilarating” influences when burning churches, or desecrating graves for that matter, but one could assume that a certain degree of sadism was inherent to these provocative acts. Their primary motivation was indeed symbolic, and they voice no regret for what they see as righteous revenge against Christianity, which they believe glorifies and caters to the “weak.”

The value of the burned churches in Norway is difficult to estimate. The loss of cultural and historical significance in a specific community (whose members were baptized, married, and buried there) can never be replaced. Even when the church burnings occurred in their own cities, where the repercussions would be impossible to ignore, the perpetrators have expressed no pity for the results of their handiwork.

Some of the most famous recent examples of church burning in Norway were at Fantoft and Holmenkollen, although neither had any congregation as such. They were more like museum pieces. In contrast, Hauketo Church outside Oslo had an active congregation. The night before October 3, 1992, the parish church was burnt to the ground. Per Anders Nordengen was parishioner of the Hauketo and Prinsdal congregations.

PER ANDERS NORDENGEN

WHAT HAPPENED AT HAUKETO?

I was awakened by my daughter who said there was a phone call for me, at 4:30 in the morning. I was told that the church was burning. I don’t think I’ve ever gotten into my clothes so fast. I drove down to the church, just a kilometer away, hoping that it was just a small fire. But seeing the flames rise into the air was quite a shock.

The day after was an incredible experience. It was a state of mourning in Hauketo and Prinsdal, and it wasn’t just us, the active churchgoers. I suddenly realized what a church means to a community. The church is a symbol of security. Everyone had been baptized or confirmed or married there. Lots of people who didn’t really go to church were crying and speaking of “our church.” Later, lots of people helped out and contributed money. So we kept going in makeshift localities; we didn’t cancel one service, one choir practice, or one activity. But it was hard work, and wore me out. That is one of the reasons why I have quit being a minister now.

PRO-GRISHNACKH FLYER

WHEN WAS ARSON SUSPECTED?

At the beginning of the investigation, the police didn’t believe in theories about Satanism. They wouldn’t have any talk about Satanism, and talk about arson was hushed up. This was shocking, since it was right after Holmenkollen was burnt. The policeman who led the investigation worked from a theory that young members of the congregation had left a waffle iron or coffee machine on the night before. He even repeated this on the TV news the day after. This was a hard blow for many.

During the investigation, it turned out that there were footprints leading to one of the windows, and the window had then been shattered. Later on, I was looking for a silver crucifix that had been at the altar. I had hoped it wouldn’t be completely destroyed or melted, but couldn’t find it. Then we found it by the exit. So the police accepted that someone had been in the church, and that there was foul play involved. The crucifix, still blackened with soot, now occupies the place of honor in our new church.

It turned out that there was a 19-year-old from the suburb next to Hauketo that was responsible. He had bought two cans of gasoline at a nearby gas station, broken into the church and set fire to it. He also took psalm books with him, which the police found in his home later.

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT THE ARSONIST?

I was asked by radio and TV to meet him, and wanted to do it. But when I heard that he didn’t regret what he had done, I felt that it was pointless to make a confrontation out of it.

I don’t think this was very ideologically motivated. I think he ended up in this scene because it was the only one in which he could gain recognition. I’ve also heard that he had a difficult upbringing. I feel more sorry for him and feel that he has been punished too harshly. The prison sentence wasn’t that hard, a year or so, but he got a damage claim of 5 million Kronor. That will destroy the boy’s future, and I think a sentence should be such that you can keep on living after atoning for your actions.

THE BURNING TIMES

For the churches that were completely destroyed, the only thing which can be done is to raise a new structure that will somehow correspond to the function of the old church. The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage estimates the value of each full reconstruction at between 15 and 30 million Kroner (between 2 and 4 million dollars). Thus, the expenses of repairing the totally damaged churches alone could run up into 300 million Kroner (40 million dollars). In addition, there come the expenses incurred by the damages on churches that were only partially harmed. The figures also do not cover the costs of the artistic decorations.

The city of Oslo took Vikernes to court to reclaim damages for the burning of Holmenkollen Chapel. The insurance company Gjensidige did the same for Skjold church and Åsane Church. The original charge was that Vikernes should compensate the entire cost of rebuilding the churches, which amounted to nearly 40 million Kroner (5 million dollars). Later, however, the sum was reduced so that Vikernes would not have to pay for the actual consecrations of the rebuilt churches, nor the cake parties later. Still, around 37 million Kroner remained to be paid, and Vikernes, unsurprisingly, did not accept the charges. He would have to go through the court system again.

NORWEGIAN HEADLINE: “BLACKLY SERIOUS”

In the courtroom, Vikernes once more played the role of Public Enemy No. 1, wearing green fatigues and leering. A certain tone was also set by the fact that all who were admitted to the courtroom were searched with metal detectors (which is not the common practice in Norway). During the trial, Vikernes’s defense attorney claimed that he had been wrongly convicted of the church burnings, the charges were outdated, and furthermore, his client had no money to pay the damages. He pressed for acquittal on all counts.

Vikernes’s protestations of innocence were not accepted by the court, and in December, 1997 he was ordered to pay 8 million Kroner (1 million dollars) in damages. Vikernes would also have to endure a 12% interest rate on the money owed, calculated from the summer of 1996. By the time of the trial the interest alone had already amounted to nearly one million Kroner.

Fantoft Stave Church became, in many ways, the primary symbol of church burnings in Norway. It was a church museum and a prominent attraction for tourists visiting Bergen. It was also used for special weddings and services on important occasions. Fantoft is under private ownership, and this would probably be the most expensive reconstruction of them all. Stave church historian David Walsten noted in 1994, “Like the legendary phoenix bird, a new Fantoft Stave Church began rising from the ashes of the old soon after the tragic fire. The owner’s intention was to construct a faithful copy of the original.”

16 The family which owns Fantoft wishes to keep the exact cost of this massive undertaking confidential.

VARG VIKERNES

HOW ORGANIZED WERE MOST OF THESE ACTIVITIES IN REALITY? WERE YOU REALLY SOME KIND OF RINGLEADER?

It was nothing like that, nothing at all. There was no such organization. I was a person who—I’m not going to say I burnt any churches, but let’s put it this way: there was one person who started it. I was not found guilty of burning the Fantoft Stave Church in Bergen, but anyways that was what triggered the whole thing. That was the 6th of June, and everyone linked it to Satanism, because of the 6-6 and it was on the 6th day of the week.

What everyone overlooked was that on the 6th of June, year 793, in Lindisfarne in Britain was the site of the first known Viking raid in history, with Vikings from Hordaland, which is my county. Nobody linked it to that—nobody.

That church is built on holy ground, a natural circle and a stone horg [a heathen altar]. They planted a big cross on the top of the horg and built the church in the midst of the holy place.

That was where it started, that was the first church. From then on it just continued. After that a church in Stavanger, south of Bergen, burned. We had no contact with them in any way. They were just another group who saw this in the newspaper and thought, wow, it was cool and we’ll do the same. They burnt the church and set fire to a small chapel. The next church that burned was Holmenkollen in Oslo, it burnt to the ground. Earlier actually, before August, another church was set on fire in Bergen, but the fire didn’t develop so it just burnt a little, and there was nothing in the newspaper, to keep it silent. Anyway, I’m actually found guilty in doing that. I was found guilty in three successful—and one unsuccessful—church burnings.

WHAT ARE THE THREE YOU ARE FOUND GUILTY OF?

Holmenkollen, Skjold Church in southern Hordaland, and Åsane Church. When I was in prison in Bergen, that church was just one kilometer away, and the under-warden came and stared at me—though he wouldn’t look in my eyes—and said: “Every day I drive to work I go past the ruins of the Åsane church and every time I think of you.” That was the first thing he told me. I was put in isolation for one year. That was a bad trip—it wasn’t the right place to come to prison. He’d been married and baptized in that church.

YOU CLAIM THE CHURCH BURNINGS ARE LINKED TO ODINISM OR ÁSATRÚ?

The point is that all these churches are linked to one person. Everything was linked to that one person, who was not Østein obviously. All the church burnings, with the exception of Stavanger because that was another group (who, by the way, have also turned into nationalistic pagans).

CAN YOU EXPLAIN IN AN ABSTRACT WAY HOW THINGS MIGHT HAVE FUNCTIONED?

Just like I said to the journalists, I might know what happened. If it turns out to be correct, well it was just a lucky guess! The first church burned on the 6th of June, with the intention probably to light a flame, to put dried grass and branches on the coal and the fire to make it big. It’s a psychological picture—an almost dead fire, a symbol of our heathen consciousness. The point was to throw dry wood and branches on that, to light it up and reach toward the sky again, as a growing force. That was the point, and it worked.

I’M INTERESTED IN THE IDEA THAT THERE WAS A GOAL BEHIND THE BURNINGS.

It would be extremely childish in any other case. The Greek guy [Vikernes is referring to the person found guilty in the arson of Hauketo Church] was influenced by us; he was trying to be one of our friends. I was just in Oslo a couple of times, coincidentally every time we burned a church. The group in Stavanger, they were doing it of their free will, of their own interest and hatred towards the church. I think the Greek guy was the only one who was doing it to impress. The people in Stavanger did it without our influence. That was in ’92. They were caught right afterwards. They were 16–17 years old, heavily into drugs and Anton LaVey.

YOU CLAIM THERE IS A GENUINE CONNECTION TO NATIONALISM.

I’ve always had that, more or less. It’s not a Satanic thing, it’s a national heathen thing. It’s not a rebellion against my parents or something, it’s serious. My mother totally agrees with it. She doesn’t mind if someone burns a church down. She hates the Church quite a lot. Also about the murder [of Østein Aarseth], she thinks that he deserved it, he asked for it. So she thinks it’s wrong to punish me for it. There’s no conflict between us at all about these things. The only thing she disliked was that I liked weapons and wanted to buy weapons, and suddenly she got a box of helmets at her place because I ordered them! Bulletproof vests, all this stuff...

THE COUNT’S EMISSARY

Churches were not the only things being disturbed by the middle of 1992. On July 26th, an 18-year-old girl, Suuvi Mariotta Puurunen, nicknamed “Maria,” crept up to a quiet house belonging to Christopher Jonsson in Upplands Väsby, near Stockholm, Sweden. She attempted to set the domicile on fire and left a note tacked to the door with a knife which read, “The Count was here and he will come back.”

17 Someone inside the house awakened at the smell of smoke and the fire was quickly put out before any serious harm was done. Jonsson is the frontman of the Death Metal band Therion. He had been involved in an argument with Vikernes. Shortly after the attempted arson on his house, Jonsson received a letter from Norway:

Hello victim! This is Count Grishnackh of Burzum. I have just come home from a journey to Sweden (northwest of Stockholm) and I think I lost a match and a signed Burzum LP, ha ha! Perhaps I will make a return trip soon and maybe this time you won’t wake up in the middle of the night. I will give you a lesson in fear. We are really mentally deranged, our methods are death and torture, our victims will die slowly, they must die slowly.

18

The actual perpetrator of the attack, Maria, would later be arrested and her diary discovered by the Swedish authorities. In speaking of her actions, she wrote, “I did it on a mission for our leader, The Count. I love The Count. His fantasies are the best. I want a knife, a fine knife, sharp and cruel... he-he.”

19 She would later be sentenced to one year’s observation in a mental hospital for her activities in connection with the Black Circle.

SWEDISH HEADLINE: “‘I AM GUILTY OF ARSON.’

MARIA’S DIARY REVEALS HER TO BE

A DEVIL WORSHIPPER”

BLACK METAL MEETS THE PRESS

In January, 1993, after seven major churches had burned in Norway, Vikernes spoke to a reporter at the Bergens Tidende daily newspaper. According to Vikernes, his interview was absurd and revealed nothing that could prove his involvement in any crime.

However, this article in all its demented glory would in fact bring intense scrutiny upon the Black Metal scene—at that point an otherwise unknown byway of underground youth culture—and link it to the burgeoning wave of inexplicable church burnings. Vikernes also provided connections to an unsolved murder of a homosexual the previous August in the Winter Olympic park in Lillehammer, a crime which the police had exhausted all their leads on and given up investigating.

VARG VIKERNES

WHAT LED TO YOU ACTUALLY BEING ARRESTED?

That was January of 1993. It was an interview and I simply said, “I know who burned the churches.” It was very simple psychology: show Odin to the people and Odin will be lit in their souls. And this is exactly what happened in Norway today, there’s a big trend in interest in Norse mythology, in all these things. And I dare say that one of the main reasons is just because of that case. I truly believe that. Why else should it be?

WHAT DID YOU SAY IN THIS INTERVIEW?

I said, “I know who burned the churches,” to the journalist, and I was making a lot of fun with him because we told him on the phone, we have a gun and if you try to bring anybody we’ll shoot you. Come meet me at midnight and all this, it was very theatrical. He was a Christian, and I fed him a lot of amusing info. Very amusing! Of course he twisted the words like usual. After he left we lay on the floor laughing.

We thought it would be some tiny interview in the paper and it was a big front page. The same day, an hour or so after I talked to him on the phone, the police came and arrested me. That was why I was arrested. I didn’t tell them anything. I talked to the police that time and I told them, “I know who burned the churches—so what?” They tried to say, “We’ve seen you at the site,” and all this, and I said, “No you haven’t!”

They bugged my friends a lot, like the Immortal guys, one of them was taken into custody. They were messing a lot with them, but they were dealing okay with it. And actually this murder that Bård Faust did, I was interviewed about that as well—they believed I did it. Then they suddenly suspected him, but I talked him so well out of it, that when he turned up to the police and said, “I want to give you an interview,” they didn’t even bother to listen to him. They said, “Who are you? We don’t want to talk to you,” and he’d done it! And of course, after some while, they had to release him, because they didn’t have anything on him. But later when he was in a cell, after twenty minutes he was crying into his lawyer’s tie and told everything. That’s the loyalty you get.

The Black Metal scene first came to the attention of mainstream, middle Norway through a cover story in the Bergens Tidende daily newspaper on January 20, 1993. Vikernes’s brooding gaze covered the front page of the newspaper under the headline “WE LIT THE FIRES.” [The text of this story is reproduced in its entirety as Appendix I.]

In the article, Varg Vikernes set the tone for the Black Metal scene’s subsequent interaction with, and portrayal by the media. In flamboyant phrases he unveiled the story of a grand conspiracy aiming to overthrow the forces of good in Norway and slaughter innocent rabbits. With quotes like “Our purpose is to spread fear and evil,” he left no doubt about his feelings toward society.

20 The article gives unique insight into how the Black Metal scene was developing at the time, and particularly how Vikernes tried to construct his image in the media.

Journalist Finn Bjørn Tønder was approached by two youths who had grown up with Vikernes. As his band Burzum was set to release a new album, they had conducted an interview with Vikernes which they hoped Bergens Tidende would print. The article closed with the remark that Vikernes had burned eight churches and killed a homosexual at Lillehammer—the latter act being the crime that Bård Eithun would later be jailed for.

Unsurprisingly, Bergens Tidende did not buy the article. However, Tønder sensed a story and set up a meeting with Vikernes with help from the two youths. In the agreement, there was the understanding that Vikernes was to read through and okay the final article. With everything thus arranged, the midnight madness at Vikernes’s pad ensued.

Tønder called Vikernes early in the evening the day afterward to read an unfinished version of the article to him on the phone. Vikernes said that it was completely in keeping with his spirit, but that he also feared that it would lead the police to him. He explained that if he didn’t pick up the phone when Tønder called him back later with the full version, he might have already escaped to Poland—supposedly to comrades there. When Tønder called back, Vikernes did-n’t answer, but he had not gone into exile. He was already downtown being questioned by the police, who had managed to find him on their own.

In an unrelated event, the police had come across some flyers for Burzum’s Aske mini-album. The flyers, like the record sleeve, proudly displayed a picture of the smoldering ruins of Fantoft Stave Church. This caught the eye and interest of the police, who simply went to the address on the flyer, where they found Vikernes.

By time the article was printed, the Bergen police had Vikernes in custody and realized that this was the youth interviewed by Tønder. In the subsequent interrogations by the police, Vikernes both claimed that he never spoke to Bergens Tidende, and that the article was incorrect. But the newspaper had four representatives present during the interview, and therefore plenty of witnesses to attest to the accuracy of the piece.

In addition to boldly presenting himself as a probable suspect in the rash of church arsons, Vikernes’s statements in the newspaper would have other residual effects. In the article, Vikernes calls the accomplice in the arson of Åsane church a “less intelligent individual” who was “utilized” by the Black Circle.

21 The person he was referring to, Jørn Inge Tunsberg from the Bergen Black Metal band Hades, ironically later talked to the police partially due to irritation at Vikernes’s unflattering description of him.

Vikernes later claimed that during questioning at his initial arrest he was also suspected for an unsolved murder in late 1992. An older black exchange student in Bergen had been reported missing some months earlier. Varg referred to his disappearance as a “murder” in a number of fanzine interviews, implying that he might have been involved with the crime. In reality, the whole incident was just a red herring. The police found out that the man had withdrawn money from his bank account after he was presumed dead. The man had a family, and in the end police concluded he’d simply run away to escape his responsibilities.

Vikernes maintained his innocence on all counts during police interrogations, and was eventually released in March for lack of evidence. Although he often intimates his involvement in the arson of the Fantoft Stave Church, it has never been proven that he committed this crime, which is considered one of the most serious and callous of the fires.

In the wake of Varg’s interrogation at the hands of the Bergen cops, a number of others in the Black Metal scene were also rounded up by different police departments and questioned regarding church arson and the murder of the homosexual in Lillehammer, including Samoth and Bård Eithun of Emperor, the latter of whom was in fact guilty of the killing. Still, evidence was scarce and all were released after being interviewed.

BÅRD EITHUN

WAS THE MURDER YOU COMMITTED IN LILLEHAMMER ON THE NEWS?

He was discovered two days later by a schoolgirl who was jogging in the area. It wasn’t on the news until then. So I talked to Østein and I talked to Vikernes too, and when he heard about this he made some other plans about burning down a church. When I came back to Oslo the evening after I was supposed to go with him and Øystein to burn down a church. So that’s what we did.

YOU PARTICIPATED IN BURNING OF THE HOLMENKOLLEN CHAPEL?

At least that one, yes. It was not anything big really. They were in the shop in Oslo talking about it. They asked me if I wanted to come with them, and yes, of course—I’d already killed a man so it’s okay to be involved in this too, to burn down a church. We went up to a church and we had bombs, but they didn’t work so we had to come back. The bomb was something that he [presumably Eithun is referring here to Vikernes] made at home. Some kind of simple bomb, it was supposed to work so that when it exploded it would light some gasoline. We broke into the church and placed the bomb on the altar of the church, surrounded by papers and gasoline. The bomb exploded but flew from where it was laying all the way into the other room inside the church. It didn’t work and did not light the gas. So we had to go up again to the church and light it by hand with a lighter. We put a lot of books, notebooks, and stuff up against the wall and we lit it. That was successful.

DID THE CHURCH BURN DOWN?

Yes, it burned down completely. Later we were watching the news. The first story in the news was about the murder which I did and the second story was about the burning, so that evening I was in the two main reports on the news. I was quite nervous, but the cops didn’t have any traces or evidence.

UGLY TRUTHS, SCREAMING HEADLINES

Once the anti-Christian crime wave was seen as emanating in some fashion from the Black Metal movement, media attention began to escalate at an exponential rate, much to the glee of the prime movers in the scene, Vikernes and Aarseth. The most infamous article published at that time is a cover feature of issue 436 of glossy U.K. Metal magazine Kerrang!, which hit the newsstands on March 27, 1993.

Dominated by a striking shot of Vikernes glaring through long locks of his darkly dyed hair, with two huge knives crossed in his fists, the cover also featured a blazing church and smaller inset photo of the band Emperor, decked out with corpsepaint, a cowled robe, and medieval weaponry. The tabloid-style headline promises: “ARSON... DEATH... SATANIC RITUAL... The Ugly Truth About Black Metal.”

22 Inside, the five-page article luridly presented the Norwegian version of Black Metal to the rest of the world. The author, Jason Arnopp, described his subjects with sensational gusto, but the bulk of the article is entirely based on alleged comments from Vikernes and Aarseth.

Under a giant quote spreading across two pages, “We are but slaves to the one with horns...” the article begins.

23 It relates the rise of church burnings, commenting that in Norway, “Black Metal has become a national menace.”

24 Along with details on Mayhem and Burzum, the America bands Deicide and VON are also mentioned as representative of the dangerous new trend. VON were merely an obscure group who managed to release one raw-sounding demo tape,

Satanic Blood, which became legendary within the Norwegian scene. In

Kerrang!, Vikernes is quoted as claiming VON was an acronym for “Victory-Orgasm-Nazis,” although this appears to be a fanciful notion on his part.

THE INFAMOUS KERRANG! COVER

The entire article is reminiscent of the earlier

Bergens Tidende piece about Vikernes. In it both Aarseth and Vikernes refer to an organization behind the crime wave in Norway, the “Satanic Terrorists,” which they are part of. Arnopp makes an interesting aside that Aarseth claims he and Vikernes “are of equal standing” within the group.

25 Aarseth also brags of ten “inner circle” members who in turn direct and manipulate a larger body of Black Metal “slaves,” and that the Helvete shop provides an economic basis for the terrorism.

26 He says he does not involve himself in the actual crimes because if he was arrested the movement would fall apart. This could support Vikernes’s later contention that Aarseth was actually afraid to take part in any of the riskier activities.

Regarding his own deeds, Vikernes is quoted by Arnopp as saying, “I’m accused of child abuse, church burnings, some murders, possession of illegal weapons... a lot of things,” but refuses to comment about any guilt on his part.

27 He describes Burzum’s

Aske mini-album as “a hymn to church burning ... It’s saying, ‘Do this. You can do this too.’ And we convert the souls of kids with our music...”

28 He declares his biggest fear above all is being committed to a mental institution.

Regarding the arson motives, Vikernes states: “We support Christianity because it oppresses people, and we burn churches to make it stronger. We can then eventually make war with it.”

29 This curious quote is revealing, and similar sentiments became part of Black Metal ideology. The Church should not be opposed for its cosmology

per se, but rather its contemporary state of weakness and its

rejection of its former draconian conduct (such as the Inquisition). Both Vikernes and Aarseth told the

Kerrang! journalist they had been raised as either agnostics or atheists.

An intriguing passage in the article discusses the genesis of the interests held by the Satanic Terrorists. Arnopp asserts that both Vikernes and Aarseth cited Venom and Bathory as early influences, and when he pointed out that Venom’s use of Satanism was purely a gimmick, Aarseth insisted the Norwegians “choose to believe otherwise.”

30 Aarseth then claims knowledge of ten assorted deaths tied to the influence of Venom’s music. “I hope Venom know about this, and they think it’s terrible. It is their legacy,” he gloats.

31KERRANG! SPREAD

The

Kerrang! exposé is also notable as it appears to be the first media story which labels the Black Metal scene as “neo-fascist.” Arnopp quotes members of Venom and mainstream U.K. Metal band Paradise Lost (who the article claims were haphazardly attacked by teenage Black Metalers while on tour in Norway), referring to the Satanic Terrorists as Hitlerian Nazis. Vikernes makes only one comment in the article which might imply any truth to this allegation: “I support all dictatorships—Stalin, Hitler, Ceaucescu... and I will become the dictator of Scandinavia myself.”

32 The last statement of this exclamation would be recycled in many of the later mass-media articles on Vikernes and Black Metal.

The Kerrang! cover story must have electrified everyone in the Norwegian underground. In addition to their newfound extracurricular activities, Vikernes, Aarseth, and the other key personalities in prominent bands like Emperor were still very much involved in their music projects—and now the biggest Heavy Metal magazine in the world had just given them an unprecedented amount of sensational coverage.

Years later in retrospect, all involved realize the absurdity of much that was said. Vikernes now insists vehemently (with what is undoubtedly significant validity) that many of his remarks were fabricated, misunderstood, misquoted, or taken out of context; others reflect back on the mentality of the scene at that time and see it as naive and deluded. Like it or not, however, the Kerrang! article was what brought Norwegian Black Metal to the rest of the world’s attention. It probably meant the crimes would eternally overshadow the music, but it was undoubtedly the best piece of international P.R. the scene would ever receive.

IHSAHN OF EMPEROR

WHY WERE THE CHURCHES BURNED?

To be honest, I think that many of the things that were done and said were just for the shock value of it. Some burned churches as a symbol against Christianity, and some burned churches just to prove themselves worthy, to say to the respected persons, “Look, I burned a church, I’m really true.” Some did it just for the sake of burning a church, just to be bad.

HOW DID YOU FIRST HEAR WHAT WAS HAPPENING?

I first heard about the church burnings on the news. Then I ran into Vikernes and he said, “Look, I burned a church!” and showed me photos. I don’t know if he showed them to everybody, but I don’t think he was very discreet about it. It was impressive—it was very evil to have burned a church, if you look at it that way. I guess I was excited about it, since anti-Christian thoughts had been discussed and I got very into it. I still have anti-Christian views, but for other reasons than I had before. I guess that’s just part of the progression.

WHAT WERE THE REACTIONS IN THE SCENE?

I remember that everybody was very inspired, thinking, “Yeah, I want to do a thing like that.” Everyone was very drawn into it, because it was our thing. It became very personal; it was almost like us against everybody. You felt that brotherhood you get when you have people who are your friends, they agree with you, and you create something together. You felt part of something very strong. Like in a band, you create something together that you’re all very fond of and you personally get very attached to the creation, or in this case, the destruction. In a sense you create war.

DID YOU FEEL THINGS WERE GETTING OUT OF HAND?

I didn’t care much about the value of human life. Nothing was too extreme. That there were burned churches, and people were killed, I didn’t react at all. I just thought, “Excellent!” I never thought, “Oh, this is getting out of hand,” and I still don’t. Burning churches is okay; I don’t care that much anymore because I think that point was proven. Burning churches isn’t the way to get Christianity out of Norway. More sophisticated ways should be used if you really want to get rid of it.

IN RETROSPECT, IS THERE VALUE IN WHAT WAS DONE?

Burning churches was a symbolic act, and it proved that some people in Norway were very much against Christianity. I also have very much respect for extreme things. Things that are extreme are fascinating, as long as they don’t go against me or those I care about. I like extreme things. It underlined and strengthened my individual feelings. It was one step further away from normal daily life for me, as for many other people.

SAMOTH OF EMPEROR

HOW ORGANIZED WERE THESE ACTIVITIES THAT WERE CONNECTED TO THE NORWEGIAN BLACK METAL SCENE?

Most of the actions were more or less “let’s do it tonight” kinds of things. But that didn’t make them any less serious. It was not like “Knights around the Round Table”... there was not a formal meeting before any act would take place, where people were told what to do and things like that. For a little while there was unity and some some strong ideas, but it soon became too unserious. Way too many people knew what was going on.

WHEN DID YOU FIRST BECOME AWARE OF THE IDEA TO BURN CHURCHES, AND FROM WHERE DID THIS ORIGINATE?

I think it was from something Vikernes hinted in a letter that made me aware of the idea. This was in ’92. Later I was shown some photos at the Helvete shop of some church ruins. I participated in the church burnings because it felt right to do so. It all happened quite spontaneously, even though the thought of doing it had been lurking in my mind for awhile. I did not really think much about it afterwards, and still don’t.

I view my arson as a sociopathic outburst, an extreme act towards the church and society. That was the intention. I still find the concept of reducing a church into a pile of ashes appealing. However, I’m not concerned about it anymore, nor do I think it’s the way to get rid of Christianity. These church fires didn’t awaken much more than a huge media hysteria and even stronger prejudice among the common people, which in the end was quite negative for us. It also led to a Black Metal hype, based upon the media, who are well-known for sensationalizing everything. Of course, we did prove a point and people are aware that there are anti-Christian forces around. Still, I think serious, intelligent propaganda is maybe a more effective way to get through to people.

DID YOU EVER HAVE THE FEELING THINGS WERE GETTING OUT OF CONTROL OR GOING TOO FAR?

I realized of course that everything had taken a very extreme turn. Anyway, I had chosen my way, so it did not disturb me really.

WHAT ARE YOUR FEELINGS ABOUT CHRISTIANITY IN NORWAY?

SAMOTH OF EMPEROR

We cannot control nature! In the big picture we are but small cosmic dust. We have no control whatsoever on the universe. The earth can strike us down and crush us all. When, or if this will happen we know not—only time will tell. I think humanity has gone “off the edge.” I don’t see any major changes amongst people of today’s world. People choose not to think. It’s a difficult thing to try to change things in the world. Christianity, for example—I think it would be close to impossible to actually wipe out Christian belief and dogma; it’s very deeply rooted in society. In retrospect to all the talk about what to do to destroy Christianity, I think there’s a lot of naiveté going around. To actually gather people and weapons for a total war against Christianity and the common society is a nice dream indeed, but hardly the reality. I even see church burning as a finished chapter. It was a good symbolic anti-Christian act, but now it’s nothing of any value at all—even the shock effect is gone. But the fact is that Christianity and all the other monotheistic religions are such destructive and false belief systems. Some people might actually open their eyes to serious and intelligent anti-Christian propaganda. The problem is that the common people don’t really care; they don’t think. It doesn’t matter for them if they are a member of the State Church or not. They are so caught up with being normal and being like everyone else, so they baptize their children in the church for that reason only. The same goes for confirmation and marriage. Most of these people have no strong religious belief, they just do it. If that “trend” would change then the Church would lose a lot of its power, because in Norway much of that power is based upon a bunch of stupid statistics. Let’s hope the next generation, our generation that is, will bring in more open- and strong-minded people who believe in individual and religious freedom, rather than narrow-minded conservatives, who believe in a type of society that we truly despise.

NORWEGIAN HEADLINE:

“THE CHURCH BURNED ON THE WEDDING NIGHT”

HELLHAMMER

HOW STRONG IS CHRISTIANITY IN NORWAY NOW?

It’s the biggest belief here.

IS A LOT OF THE “SATANISM” JUST A REACTION AGAINST THAT?

I don’t know, because from the first time I was against the burning of the Norwegian churches. Totally. I told them, why not burn up a mosque, the foreign churches from the Hindu and Islamic jerks—why not take those out instead of setting fires to some very old Norwegian artworks? They could have taken mosques instead, with plenty of people in them!

FANNING THE FLAMES

The church burnings which began in the spring of 1992 would continue until the present, although they have not received as much publicity after the court trials were concluded in 1994. When we interviewed him in 1995, Vikernes claimed he knew of approximately thirty church arsons which had occurred the previous year, and stated that they continue to take place. Asked why there was little media coverage of the ongoing trend, he explained:

Most of [the churches] are just damaged. If something burns to the ground you usually hear about it. But there are a lot of smaller chapels which have been burned, and Christian schools, and we read almost daily in the papers about grave desecrations. A week doesn’t go by without a report of grave desecrations.

33

A November 7, 1995 article in Norway’s Aftenposten newspaper focused on the history of the church burnings, listing the following “official statistics”: 1992—thirteen fires, ten cases solved; 1993—ten fires, five cases solved; 1994—fourteen fires, seven cases solved; 1995—seven fires, three cases solved at the time of the article. These figures vary considerably from some of Vikernes’s claims, although they add up to a startling forty-four church attacks over four years. If Varg is to be believed, the number could be even higher, and more arsons have occurred since the end of 1995. A spokesman for the Kripos (roughly the Norwegian equivalent of the FBI) stated to Aftenposten that in every case which was solved, the culprits were Black Metal “Satanists.”

BATF ARSON PREVENTION BOOKLET

Whether the church burnings and other acts of vandalism in Norway will eventually stop is difficult to say. As chapter 12 will reveal, the trend has spread to nearby Sweden and into some countries in Central Europe. A purely coincidental development would appear to be the rash of churches recently hit by arson in the United States. While this trend appears to have begun in the early 1990s, it has been escalating. In 1995–96 there were investigations into 429 incidences of church arsons, bombings, or attempted bombings. The epidemic mostly afflicted poor black churches in the South, and public outrage against a presumed conspiracy of racist terrorism resulted in the President’s formation of a National Church Arson Task Force in June, 1996. The Task Force has since concluded that no nationwide conspiracy exists, and suspects arrested in relation to the the fires have been blacks and Hispanics as well as whites. The motives in specific incidents have ranged widely, from revenge to vandalism to racial hatred.

“BURN YOUR OWN CHURCH” KIT FROM OSLO MAGAZINE, GATE AVISA

Church arson has also been used as an element of intimidation in the centuries-old conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland. The April, 1997 issue of

An Phoblacht, a pro-Republican newspaper, features photos of the burnt-out remains of two Catholic churches hit with firebombs, and the accompanying article refers to at least eight different arson attacks on Catholic churches or religious buildings. A quote from Sinn Fein representative Gerry Adams indicates that the terrorist strategy of church burnings is utilized by both sides in the ongoing civil war: “Attacks on Catholic churches are just as wrong and sectarian as those carried out on Protestant churches.”

34Most observers might find it an inapt comparison to speak of church burnings by Norwegian teenagers in the same breath with those committed by the Ulster Defense Association or Irish Republican Army in Ireland. No matter the country or context, however, the tangible effect of a destroyed church on its congregation and surrounding community is the same. And if Varg Vikernes is to be believed, the church burnings in his country serve a similar function to those in Northern Ireland—that of terrorism aimed toward the spiritual sanctuaries of one’s enemy. According to Vikernes, the Norwegian arsons are symptoms of a religious struggle even more deep-seated and long-standing than the Catholic/Protestant sectarian conflict in Ireland. They are symbolic acts of terror against Christianity itself, and Vikernes sees no reason to apologize for that. To him, the torching of a House of God is simply one more weapon to be utilized in the arsenal of an unholy war.

BURNED CATHOLIC CHURCH FROM AN IRA NEWSPAPER