resurge - 1. to rise again, as from death or from virtual extinction.

resurgent. adj. rising or tending to rise again; reviving.

atavism - 1. Biology. the reappearance in an individual of characteristics of some remote ancestor that have been absent in intervening generations. 2. reversion to an earlier type.

—Random House Dictionary of the English Language 1

ARCHETYPES ARE LIKE RIVERBEDS WHICH DRY UP WHEN THE WATER DESERTS THEM, BUT WHICH IT CAN FIND AGAIN AT ANY TIME.9

RESURGENT ATAVISM: THE METAPHYSICS OF HEATHEN BLACK METAL

A WAVE OF VIOLENCE ERUPTS ACROSS AN OTHERWISE TRANQUIL LANDSCAPE, a conservative but humanistic society which has always ensured that its citizens are well fed and finely educated. Whatever their future station in life, they can count on comfort, security, and all the other benefits of a country with one of the highest standards of living in the world... yet the young dream of murder, blood sacrifice, revenge.

The Christian religion plays no great part in their lives, though its secular counterpart, the system of social democracy, offers them great opportunity. They reward such benefaction with a curse of fire, basking in the glory of destruction. Nothing excites more than the thought of chapel and vicarage ablaze, illuminating the womb of the night sky with darting flames, dancing and thrusting upward. The beauty is in ruins; a temple laid to waste becomes an aesthetic victory.

Their law of the strong scorns pity as a four-letter word; they await the day it is banished from the dictionaries. They despise doctrines of humility. Christ’s Sermon on the Mount is even worse poison to their ears. War is their ideal, and they romanticize the grim glory of older epochs where it was a fact of life.

Where is the source for such a river of animosity and primal urges? Did torrents of hatred arise simply from the amplification of a phonograph needle vibrating through the spiralled grooves of a Venom album? Is Black Metal music possessed of the inherent power to impregnate destructive messages into the minds of the impressionable, laying a fertile seed destined to sprout into deed? To an enlightened mind it would seem unlikely.

If there is no clear, rational explanation for why Black Metal went to such hellish extremes, an investigation of the genre’s more irrational or visionary aspects is in order. The following two chapters investigate the metaphysical and spiritual underpinnings of Black Metal, and how they have manifested in the real world.

Black Metal is primarily seen as a musical movement tied to Satanism, and the varying implications of this will be touched upon in Chapter 10. Many principal figures in Black Metal—Varg Vikernes especially—have also pledged a dedication to what they claim are heathen ideals. Scandinavia was one of the last European cultures to convert to Christianity. The explosion of Black Metal there warrants a look at possible correlations between ancient Norse heathenism and modern musical extremism.

AORTA JOURNAL

THE WILD HUNT DRAWS NIGH

In one of many articles detailing his interpretations of Nordic heathen cosmology written from prison, Varg Vikernes elaborates at length on his fascination for the folklore of the Oskorei:

The demonic-Odhinnic deathcult is one of the nuclei of Germanic volk-culture; connecting the living with the dead. Oskoreien—the “Ride of the Dead” during the Holy twelve or thirteen nights of Yule and at time of fasting—or Åsgardsreien (as it is also known) originate from the martial/mystical mystery-society of “Werewolf-warriors” selected and initiated after severe rules and regulations. Oskoreien/Åsgardsreien will be wearing black shields and warpaint on their bodies, symbolizing dæmonic/lycanthropic transformation... Such a so-called Varulv Orden [Werewolf Order] will rush forward at night with wonderful wildness.

3

Vikernes goes on to describe various permutations of this Odinic death cult, explaining that a ritual-initiation will lead to a higher spiritual state, culminating in a joint ascension with one’s ancestral spirits of something he calls the “Transcendental Pillar of Singularity”—also referred to in a Burzum song title. Before this is dismissed as nothing more than mindless verbiage on Vikernes’s behalf, it deserves a closer examination.

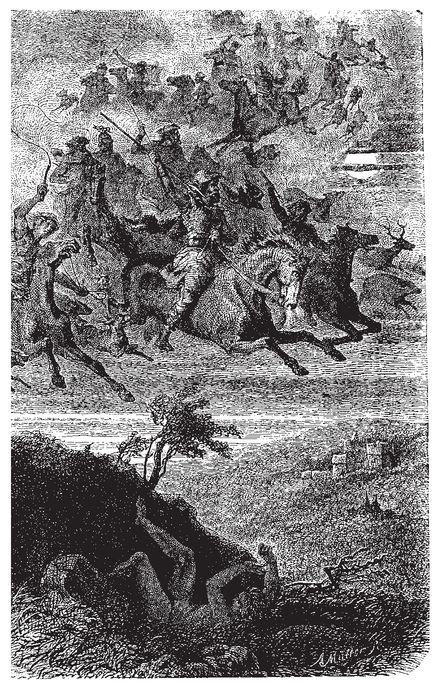

NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGRAVING OF THE WILD HUNT

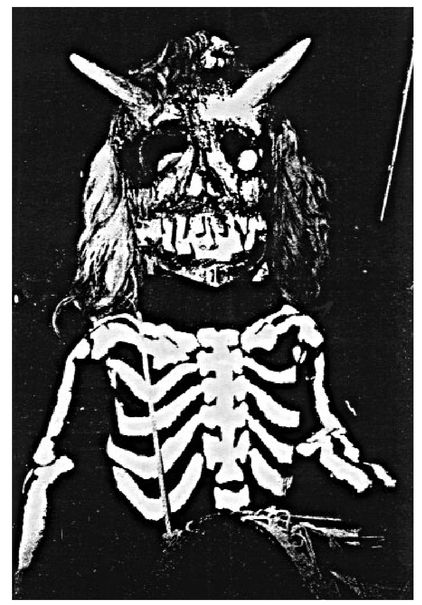

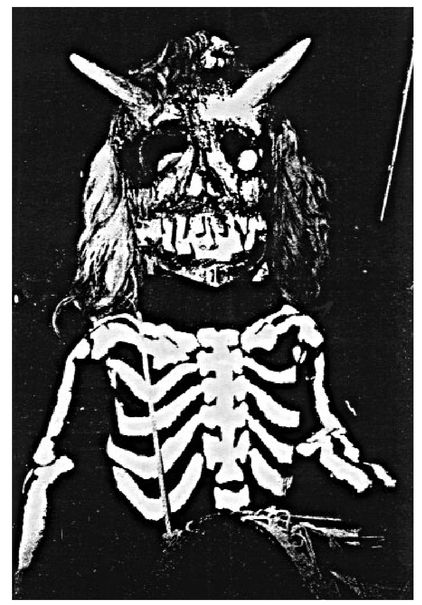

After reading a number of similar texts by Varg Vikernes, the Austrian artist and occult researcher named Kadmon was inspired to investigate in detail what enigmatic connections might exist between the phenomena of modern Black Metal and the ancient myths of the Oskorei. The Oskorei is the Norse name for the legion of dead souls who are witnessed flying, en masse, across the night sky on certain occasions. They are rumored to sometimes swoop down from the dark heavens and whisk a living person away with them. This army of the dead is often led by Odin or another of the heathen deities. Throughout the centuries, there are many reports from people who claim to have experienced the terrifying phenomenon—they attest to having seen and heard the Oskorei with their own eyes and ears. The tales of the Oskorei also refer to real-life folk customs which were still prevalent a few hundred years ago in rural parts of Northern Europe. They normally occurred at Yule time, when groups of rowdy young men would ride by night in groups on horseback, often frightening the villagers with the sound and fury of their arrival. Folklorists have attempted to explain the legends in different ways. Kadmon’s essay on the Oskorei and Black Metal is reproduced as Appendix II. It is a fascinating comparison of details in the recorded folk tales of the Oskorei and uncanny similarities to many of the traits which are distinct facets of modern Black Metal—noise, corpsepaint, ghoulish appearances, the adoption of pseudonyms, high-pitched singing, and even arson. Kadmon discovers further correspondences with the old tradition of the haunting and costumed Perchten parades which still take place in Austrian towns on certain festival days. These winter folk traditions may have roots in the older worship of the Germanic winter/sky goddess Perchta. Today they comprise processions of both the benign or beautiful looking Perchten, as well as their sinister and demonically-masked counterparts the Schiachperchten.

SCHIACHPERCHTEN MONSTER FROM AORTA JOURNAL

Certain general connotations and correlations of the Oskorei legends are significant. The phenomenon appears particularly potent in Norway, although it has manifested in all the Scandinavian lands in differing forms. In German folklore, stories of the Oskorei correspond directly to the “Wild Hunt,” also termed “Wotan’s Host.” Wotan (alternately spelled Wodan) is the continental German title for Odin, Varg Vikernes’s “patron deity,” thus he might feel an obvious affinity to the stories of the Oskorei due to their “demonic-Odhinnic deathcult” connection, as he terms it. In a number of the legends, the spirits of the Oskorei take on a sinister air, and are treated as if demons. Crosses are employed, à la Dracula, to ward them off. Aschehoug and Gyldendal’s Store Norske Leksikon (The Large Norse Encyclopedia) states the name Oskorei can be interpreted as “the terrible ride,” and describes it in detail:

There were often fights and killings at those places Oskoreia stopped. They could drink the yule ale and eat the food, but also carry people away if they were out in the dark. One could protect against the ride by gesturing in the shape of a cross or by throwing oneself to the ground with the arms stretched out like a cross. The best way was to place a cross above all the doors. Steel above the stalls was effective as well. The Oskorei was probably regarded as a riding company of dead people, perhaps those who deserved neither Heaven nor Hell. One must take into account the midwinter darkness and the common belief that the dead return at yuletide.

4

THE LURE AND LORE OF ARCHETYPES

Given the dark, ghoulish, and quasi-diabolical nature of the Oskorei, it is not surprising that Vikernes and others in the Black Metal scene might develop a visceral fascination for it. Images of the frenzied hunt across the night sky were not unfamiliar to the music scene; the cover of Bathory’s first “Viking” album, Blood Fire Death, features a haunting depiction of the Oskorei in action. The remarkable development is how so many of the minute details of the legends would inadvertently or coincidentally resurface in unique traits of the Norwegian Black Metal adherents. This behavior had already become prominent years before the scene acquired its current attraction toward Nordic mythological themes, and before Vikernes ever began writing commentaries on such topics.

When Norwegian Black Metal sparked its initial flurries of mainstream publicity, it was generally portrayed as a neo-fascistic or despotic strain of Satanism. At the same time, there were always elements present which harkened back to the Viking age, or at least displayed a superficial identification with Viking strength and barbarism. The basis for such attitudes was rarely explained with any degree of depth until recently, when previously peripheral elements became driving forces for many of the bands and personalities.

Varg Vikernes is today the most overt of all the heathen advocates within Black Metal, but he is far from alone in his interests and sources of inspiration. Many of the “Satanic” bands even evince a strong fascination for native folklore and tradition, seeing them as vital allegories which represent primal energies within man. This type of viewpoint is expressed well by Erik Lancelot of the band Ulver:

The theme of Ulver has always been the exploration of the dark sides of Norwegian folklore, which is strongly tied to the close relationship our ancestors had to the forests, mountains, and sea. The dark side of our folklore therefore has a different outlook from the traditional Satanism using cosmic symbolism from Hebraic mythology, but the essence remains the same: the “demons” represent the violent, ruthless forces feared and disclaimed by ordinary men, but without whom the world would lose the impetus which is the fundamental basis of evolution.

Our use of old Norwegian imagery is not an end in itself, but rather a manner to symbolize our own thoughts with pictures close to our own traditions. ... We believe that the underlying, metaphysical source of life is essentially what “white light” religions have regarded as “evil” because it is ruthlessly and aggressively vital, untamed by any restrictions lest they be the morals imposed by “reason” or “culture” in order to subjugate the expansion of force.

5FOREST ENGRAVING FROM A NORWEGIAN BOOK OF FOLKTALES

Varg Vikernes speaks of Burzum as a resurrection of primordial forces. In explaining his justification for the church burnings he states it was to “Show Odin to the people and Odin will be lit in their souls,” imbuing his actions with an atavistic motive.

6 When asked of his attitude toward the Norse gods in an interview with

Descent magazine, Varg elaborated:

They’re not “gods,” but Áses. They’re the archetypes of the Northern race. Thus within me. They’re the names we gave to what once was, during what once was so that our posterity should never forget. Alas, only a few of us remember, and we always will. I will never forsake my forefathers, my nature, or myself. And truly this is what heathendom is—our nature.

We all learn about the Christian interpretation of heathendom, making it “mythology.” More and more are waking up from the sleep of idiocy and following their nature. By showing my interpretation to the people, I light the heathen fire in their souls. It’s inevitable, because they are our archetypes. Odin wins.

7

Varg’s statements may sound irrational, but they are not unique. The renowned psychologist Carl Gustav Jung developed his own theories of the collective unconscious, which may manifest in different groups of people based on the archaic archetypes of their culture. He explains this in terms of “primordial images” in his 1928 work Two Essays on Analytical Psychology:

There are present in every individual, besides his personal memories, the great “primordial” images, as Jacob Burckhardt once aptly called them, the inherited powers of human imagination as it was from time immemorial. The fact of this inheritance explains the truly amazing phenomena that certain motifs from myths and legends repeat themselves ... It also explains why it is that our mental patients can reproduce exactly the same images and associations that are known to us from the old texts.

ICY NORWAY

The primordial images are the most ancient and the most universal “thought-forms” of humanity. They are as much feelings as thoughts; indeed they lead their own independent life...

8

As Kadmon’s essay illustrates, similarities between aspects of Norwegian Black Metal and the furious, Wild Hunt of the dead are startling. Can this be explained as a Jungian “primordial image” resurfacing in a modern generation of youth? Kadmon also points out a few strong contrasts between the rural folklore and Black Metal, which he sees as an urban phenomena. He is not entirely correct in this assertion, however, as many of the Norwegian Black Metal musicians do not come cities such as Oslo, Bergen, or Trondheim, but live in small villages in the countryside. And Varg Vikernes, too, is proud to make the distinction that he is originally from a rural area some distance outside of Bergen, rather than the city itself. Further examples can be found with the members of Emperor, Enslaved, and a number of other bands. Considering the intriguing parallels drawn in Kadmon’s essay, the subject of the relationship between heathen metaphysics and Black Metal—and whether some sort of resurgent atavism may be at their root—is worth investigating in detail.

There is no doubt that a vast number of those involved in Black Metal emulate a barbaric image in their appearance and demeanor, statements and lyrics. The music could certainly be similarly described as barbarous by an unwary listener, although it is often complex and beautiful as well.

COUNTRYSIDE OF TELEMARK

Beyond drawing inspiration for such an outlook from Heavy Metal’s long tradition of masculine motifs, and more specifically from the “Viking trilogy” of influential Bathory albums, many in the scene appear to take things more seriously than simply erecting a façade of fantasy imagery. Besides Bathory, one other early Scandinavian Metal band had also extolled the religion and lifestyle of the Vikings in their music, a group from the ’80s called Heavy Load. Possibly they also inspired some of the kids later involved in Black Metal, and indeed they have been mentioned with appreciation by some close to the scene, like Metalion.

NORWEGIAN MOUNTAIN RANGE

JOHNNY HEDLUND

Among the Death Metal bands, we have noted the presence of Sweden’s Unleashed, who stand quite apart from the rest of their peers in terms of their lyrical and spiritual inspiration. Unleashed have always made clear their admiration for the pre-Christian Norse religion of Ásatrú. Singer and bassist Johnny Hedlund explained the source for his impulse toward these themes:

The influences that I have are actually from my ancestors and from sitting in the countryside and feeling the power of nature—just by sitting there knowing that my grandfather’s, father’s father was standing here with his sword ... by knowing that you are influenced from it.

9

Similar sentiments are often voiced by many of the Black Metal bands, who speak of the Norwegian landscape and countryside in tones of reverence. In explaining one of his personal sources of inspiration, Vikernes once commented to a journalist at

Terrorizer magazine, “I strongly recommend you to try and walk in the middle of a winter night in a Norwegian forest all alone, and you will understand what I mean: it actually speaks.”

10 Obviously Vikernes is not the only one who feels this attraction, since nearly every single Black Metal band has had themselves photographed amongst snow and trees.

The group Immortal even went so far as to make a professional video clip with every band member shirtless in the midst of a freezing winter snowscape, furiously playing one of their songs. A video for the Burzum song “Darkness” goes much further, leaving out any human traces whatsoever—the entire eight minute clip is based on images of runic stone carvings, over which shots flash of rushing storm clouds, sunsets, rocks, and woods. Co-directed by Vikernes from prison via written instructions, the result is impressively evocative despite the absence of any storyline or drama.

WOTAN REDIVIVUS

The end of the twentieth century has witnessed attempts by contemporary men and women to resurrect a wide array of pre-Christian religions. The instinctual or atavistic nature of heathen religion itself is nothing new, and many of these “revivalists” have experienced its magnetic allure. The gods of the North seem particularly prone to stirring feelings which may unexpectedly resurge among the descendants of those who once worshipped them.

According to Carl Jung, it is not always modern man who actively seeks to consciously revive a pre-Christian worldview, but rather he may become involuntarily possessed by the archetypes of the gods in question. In March, 1936, Jung published a remarkable essay in the Neue Schweizer Rundschau, which remains highly controversial to the present day. Originally written only a few years after the National Socialists came to power in Germany, it is entitled “Wotan.”

Jung states in no uncertain terms his conviction that the Nazi movement is a result of “possession” by the god Wotan on a massive scale. He traces elements of the heathen revival back to various German writers, Nietzsche especially, who he feels were “seized” by Wotan and became transmitters for aspects of the god’s archetypal nature. He states, “It is curious, to say the least of it ... that an old god of storm and frenzy, the long quiescent Wotan, should awake, like an extinct volcano, to a new activity, in a country that had long been supposed to have outgrown the Middle Ages.”

11Jung would some years later reveal his conviction that both Nietzsche and he himself had experienced personal visits in their dreams from the ghostly procession of the “Wild Hunt,” the German equivalent of the Oskorei.

In the “Wotan” essay he goes on to describe

Jugendbewegung (Youth Movement) sacrifices of sheep to Wotan on the solstice, and explains in detail his belief that Germany is being led away from Christianity via “possession” by the ancient deity. Jung concludes his explication with the prediction that while Germany in the ’30s may be under the specific sway of Wotan’s more furious attributes, in the “course of the next few years or decades” other, more “ecstatic and mantic” sides of the god’s archetype will also manifest themselves.

12This belief in the atavistic power of the old Norse religion is shared by Stephen McNallen, who is generally credited with sparking the current day revival of Ásatrú or Odinism in the English-speaking world. In the late ’60s, McNallen felt powerfully drawn to investigate the religion of the heathen Norsemen, and what he discovered so inspired him that he composed rituals of worship for the Norse/Germanic gods and set about to find others on a similar spiritual path. After founding a small group, the Viking Brotherhood (which evolved into the Ásatrú Free Assembly), McNallen discovered that a number of people in distant parts of the Western world had also felt an identical “Odinic” pull at the same point in time as he had. Without having any knowledge of one another, groups dedicated to the worship of the gods of Northern Europe simultaneously sprung up in England, Iceland, and on the East Coast of the U.S., along with McNallen’s efforts in Texas. Why this revival would occur in such an “organic” and synchronistic manner is difficult to say—the Jungian explanation of Wotan redivivus is as reasonable as any.

In Norway and Sweden there has also been growing general interest in the indigenous religion of their forefathers, to the point that at least one heathen group, Draupnir, has been recognized as a legitimate religious organization by the Norwegian government. Along with them, other Ásatrú organizations such as Bifrost also hold regular gatherings where they offer blot, or symbolic sacrifice, to the deities of old.

There is absolutely no specific connection between these Nordic religious practitioners and the Black Metal scene. In fact, public assumptions that such a link would exist have been a severe liability to these groups. Dispelling negative public impressions of their religion is made considerably more difficult with characters like Vikernes speaking so frequently of his own heathen beliefs to the press.

When told of Draupnir’s irritation at constantly having to publicly state their lack of any common ground with Black Metal and Satanism, Vikernes appears to naively misunderstand that his own declarations are what caused such difficulties in the first place:

This situation with the Christians is like a new Inquisition. People like Draupnir would have been burned at the stake as Devil worshippers. But today they put us in prison. If any Ásatrú group does not stress that they are not Satanists, then they are accused of being that, anyway. So they have to stress that we are not this or that. It must be quite annoying. It’s annoying for me as well, because I’m being called a Satanist all the time.

13“THE WILD HUNT” BY GERMAN ARTIST FRANZ VON STUCK

THOR (DETAIL FROM A PAINTING BY M.E. WINGE)

Ásatrú has no central body to decide who or who isn’t part of it, and of course no one can stop Vikernes from explaining his own heathen worldview as he sees fit—or making his bold assertions that the church burnings, grave desecrations, and other crimes were done in order to “show Odin to the people.”

14 Vikernes’s extreme and bloody interpretation of indigenous Norse religion is just as problematic to the neo-heathen groups as was his flaming-stave-church and brimstone variety of Satanism a few years earlier to organizations like the Church of Satan. When contemporary figures sought to revive the old religion of Northern Europe, they had not intended to bring back uncontrollable barbarism and lawlessness with it.

One can see a clear shift amongst the Black Metal bands toward a heathen outlook, although few, if any, of them appear to have been influenced by any outside group such as Draupnir or Bifrost. Many of the more Satanic bands have altered their focus, removing explicit reference to the Devil and replacing it with more vague allusions to the “old gods.” Thor’s Hammer amulets can be seen around the necks of just about every band member of any Scandinavian group in promo photos.

Burzum, Enslaved, and Einherjar are just a few of the dozens of groups who play music that is unequivocally focused towards Norse religious themes. These obsessions (exemplified in some of Vikernes’s more far-fetched statements, or musically in Enslaved’s recording an entire album sung in Old Icelandic language) clearly go beyond the point of simple, passing interest. But it remains to be seen where such a road, stretching as it does from the farthest reaches of Nordic heritage and into the vast realm of Skuld, the future, will finally lead.

In Jung’s “Wotan” essay, he states in his conclusion that in addition to its bloodier manifestation, he also believes the “prophetic” aspect of Wotan will become apparent in future. Did elements of the Oskorei, linked so strongly as they are to Odin/Wotan, in some tiny way serve as premonitions which would re-manifest in the centuries of “civilized” behavior that followed? There is another obscure old fable of the Oskorei, where they fetch a dead man up from the ground, rather than their usual choice of someone among the living. It was collected by Kjetil A. Flatin in the book Tussar og trolldom (Goblins and Witchcraft) in 1930. If the folkloristic and heathen impulses of Norwegian Black Metal are in fact some untempered form of resurgent atavism, then this short tale is even more surprising in its ominously allegorical portents of events to come over sixty years later with Grishnackh, Euronymous, and the fiery deeds that swirled around them:

On Aase in Flatdal, they were drinking and carousing one evening around Christmas time. Two men strapped themselves together with a belt and fought with knives. One of the men was stabbed and lay dead on the floor. Then the Oskorei came riding in through the door, took the dead man with them, and threw a burning torch on the floor…

15

IN THE SHADOW OF WOLVES

While researching the possible similarities between Nordic cosmology and elements of Black Metal, other intriguing material came to light. Just as Euronymous and Dead fulfilled the grim destinies of their adopted names, this can be seen in other cases as well. An investigation into the old Nordic connotations of the name taken on by Vikernes unearthed some startling correspondences which would appear to indicate the most obscure and archaic meanings of the word itself were destined to make themselves manifest.

Originally bestowed with “Kristian” for his first name, Vikernes found this increasingly intolerable in his late teenage years. When he first introduced himself to the Black Metal scene it was still his forename. Sometime in 1991–92 he legally changed his name to “Varg.” His choice of a new title is curious in light of the actions he would later commit, and the legend that would surround him—although he claims to have adopted it mainly for its common meaning of “wolf.” If one understands the etymology and usage of the word varg in the various ancient Germanic cultures (and there is no evidence that Vikernes did at the time of his name change), his decision becomes downright ominous.

A fascinating dissertation exists entitled Wargus, Vargr—‘Criminal’ ‘Wolf ’: A Linguistic and Legal Historical Investigation by Michael Jacoby, published in Uppsala, Sweden, but written in German. It is a highly detailed, heavily referenced exploration of the Germanic word Warg, or vargr in Norse.

The paper begins with a section “The Term Warg as a Designation for the Criminal in Ancient Germanic Sources,” discussing the connotations of the root word among the various Northern European cultures. It appears in the different language dialects, but always with a negative implication when descriptive of men, conveying the sense of “criminal,” “outlaw,” “outcast,” “thief,” “malefactor,” “evil being,” “the damned one,” and indeed, even “Devil.”

WEREWOLF

The designation was used in the oldest written laws of Northern Europe, often with a prefix to add a specific legal meaning, such as

gorvargher (“cattle thief”) or

morthvargr (“killer”). Comparative mythology researcher Mary Gerstein, author of the essay “Germanic

Warg: The Outlaw as Werewolf,” notes that in the old Icelandic legal text, the

Grágás, “one finds

morthvarg ‘murder-

varg’ as a term for a particular subclass of outlaw ... [which] implies killing furtively ... as well as the attempt to conceal the crime. It is the crime of a skulking werwolf.”

16 The term also appears in the ancient Norwegian legal context, to designate the criminal who performed the

exact crime Varg Vikernes would become renowned for a millennia later:

brennuvargr (“arsonist” or literally, “fire wolf”). In researching the

Gulathingslov, the early Norse laws, Gerstein concludes:

The term Varg is also rare and highly specialized; it occurs as a technical term for an outlaw not known to be such, úvísavargr, and as a term for a man outlawed for arson: “tha er hann útlagr oc úheilagr oc heitir

brennuvargr” (he shall be outlawed and deprived of all rights and shall be called “fire

-varg”) ...

varg as it occurs in the earliest Old Norse codes is an item of petrified legal vocabulary, retained in expressions involving oral pronouncement of outcast status for especially odious crimes, such as arson, oath breaking, and secret slaying.

17ULVER THE MADRIGAL OF NIGHT

Jacoby’s research continues with an investigation and examination of the most noteworthy crimes which were strongly connected to the word. These are: grave robbery, treason, theft, and manslaughter. A case can be made that Varg Vikernes fulfilled each one of these specific connotations in some respect. Describing the first of the crimes, there is clause in another ancient Germanic legal text, the Salic Law, which states: “If any one shall have dug up or despoiled an already buried corpse, let him be a

varg.”18 Vikernes’s advocacy of, and participation in, grave desecrations surely qualifies him for this designation. As regards treason, Varg proudly states a desire to see the current government of Norway overthrown, and he identifies with the man whose name has become synonymous with treason in the international vocabulary, Vidkun Quisling. Vikernes has also often been called a “traitor” by others in the Black Metal scene for killing Øystein Aarseth. Vikernes was found guilty of theft—he stole 150 kilos of explosives and had this stored in his apartment at the time of his arrest. The old Germanic laws do not appear to make a distinction between first-degree murder and manslaughter, and refer only to the latter. Vikernes was convicted of murdering Euronymous, although he insists this was only manslaughter, done in self-defense. It is eerie and uncanny that someone could live up to their name so well, even down to the subtleties of its earliest etymological essence. As a result of his actions, he has truly become an “outlaw” and “outcast” in the eyes of society.

ILLUSTRATION OF A THIEF HUNG WITH A WOLF FROM

A 1907 EDITION OF SAXO’S HISTORY OF THE DANES

The Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould, in his Book of Werewolves, writes of the other meanings inherent to Vikernes’s chosen namesake:

The word vargr, a wolf, had a double significance, which would be the means of originating many a were-wolf story. Vargr is the same as u-argr, restless; argr being the same as the Anglo-Saxon earg. Vargr had its double signification in Norse. It signified a wolf, and also a godless man. [...] The Anglo Saxons regarded him as an evil man: wearg, a scoundrel; Gothic vargs, a fiend. ... the ancient Norman laws said of the criminals condemned to outlawry for certain offenses, Wargus esto: be an outlaw! [be a varg!] ... among the Anglo Saxons an utlagh, or out-law, was said to have the head of a wolf. If then the term vargr was applied at one time to a wolf, at another to an outlaw who lived the life of a wild beast, away from the haunts of men—“he shall be driven away as a wolf, and chased so far as men chase wolves farthest,” was the legal form of sentence—it is certainly no matter of wonder that stories of outlaws should have become surrounded with mythical accounts of their transformation into wolves.

19The above elucidation reveals a few further elements which reflect Vikernes’s character and circumstances. He is by nature an extremely restless person, brimming with energy and possessed of a defiant gleam in his eye. His position of “outlaw” goes beyond just his status with everyday society, since a number of people in the Black Metal subculture have also sworn they plan to kill him if given the chance. This is much like the position of the outlaw in older times, banished from society and fair game for anyone who would deem to destroy him.

There are a number of other associations which come to light upon closer consideration of the statements and actions of Vikernes, in his persona as the heathen “Varg.” As can be seen from the Baring-Gould quote above, the wolf connotation of the term later became associated with werewolves, and in certain sources the Devil himself is referred to as a werewolf. However, this negative outlook on wolves appears to surface after the onset of the Christian period of Europe; the pre-Christian heathens had a quite different perception.

A number of Black Metal bands display a fascination for the wolf. The most obvious example is Ulver, whose name itself means “wolves” in Norwegian. Their most recent recordings have been based entirely on wolf-lore. The band’s guitarist Erik Lancelot states:

The mythical wolf is a Satanic character. He is often pictured as a solitary antagonist, a representative of animalism appearing before humans to promote values of selfishness and brute force, as for instance in the tale of “Little Red Riding Hood” and certain tales of La Fontaine. The wolf lives in the forest, symbol of the demonic world outside the control of human civilization, and serves thus as a link between the demonic and the cultural, chaos and order, light and dark, subconscious and conscious. Still I do not by this mean to say that the wolf represents the balance point between good and evil—rather he is the promoter of “evil” in a culture which has focused too much on the light side and disowned the animalistic. He symbolizes the forces which human civilization does not like to recognize, and is therefore looked upon with suspicion and awe.

20

In the older Viking times, wolves were totem animals for certain cults of warriors, the Berserkers. A specific group is mentioned in the sagas, the Ulfhethnar or “wolf-coats,” who donned the skin of wolves. Baring-Gould recounts the behavior of the Berserks who, wearing these special vestments, reached an altered state of consciousness:

They acquired superhuman force ... No sword would wound them, no fire burn them, a club alone could destroy them, by breaking their bones, or crushing their skulls. Their eyes glared as though a flame burned in the sockets, they ground their teeth, and frothed at the mouth; they gnawed at their shield rims, and are said to have sometimes bitten them through, and as they rushed into conflict they yelped as dogs or howled as wolves.

21

The Berserks were described in the old chronicles as “men of Odin,” the god to whom Vikernes also claims exclusive dedication. Wolves are sacred to Odin, the “Allfather,” who is usually accompanied by his own two wolf-elementals, Geri and Freki. Many Germanic personal first names can be traced back to another root word for wolf, ulv or ulf, so this was clearly not an ignoble or derisive connotation, except in its varg form.

THE MASKS OF ODIN

Odin himself is a challenging deity, providing an archetype for the Faustian seeker: he who makes a dangerous pact in return for increasing knowledge and experience. Some of the more notable attributes of the character of Odin and the cult that surrounded him in ancient Scandinavian tribal society are exceedingly sinister. In the old sagas he is bestowed with myriad names and titles, some of which include Herjan (“War God”), Yggr (“the Terrible One”), Bölverkr, (“The Evil Doer”), Boleyg (“Fiery Eyed”), and Grímnir (“the Masked One”).

ODIN CARVING FOUND IN HEGGE STAVE CHURCH

Odin is mentioned in the

Elder Edda as first having brought battle to the cosmos:

“On his host his spear did Odin hurl / Then in the world did war first come,”22 states the Eddic poem “Voluspá.” His early worship demanded the sacrifice of innocent men. Odin is often referred to as a great “stirrer of strife.” Comparative mythologist Georges Dumézil remarks:

The character of Odin is complex and not very reassuring. His face hidden under his hood, in his somber blue cloak, he goes out about the world, simultaneously master and spy. It happens that he betrays his believers and his protégés, and he sometimes seems to take pleasure in sowing the seeds of fatal discord...

23 It is not difficult to see the appeal of the Odin archetype for those who assume the role of the heretic, pariah, or outsider. Varg Vikernes is all these things, and his long-standing obsessions with weapons, warfare, struggle, and death also fit into an Odinic paradigm. In her essay on the word Warg, Mary Gerstein also discusses comparative symbolism between Odin, who hung on the world tree Yggdrasil for nine nights in order to gain wisdom, and Christ, who was hung on the cross as an outlaw, only to be reborn as an empowered heavenly deity. Vikernes, despite his heathenism, has in certain respects set himself up as both avatar and Christ-like martyr for his cause, willing to suffer in prison for his sacrifice. Gerstein also draws parallels between Odin in his mythological role as the binder of foes, and his relationship to those who are deemed a criminal varg:

Odin differs ideologically from other [Indo-European] binder gods in his essential amorality: he delights in strife between kinsmen and urges men to break their vows. The strangled

warg belongs to him more from a sense of “like seeking like” than in punishment. His very name indicates his nature; Adam of Bremen’s “Wodan, id est furor” [“Wodan, that means fury”] stands fast: Odin is the embodiment of every form of frenzy, from the insane bloodlust that characterized the werwolf warriors who dedicated themselves to him, to erotic and poetic madness.

24

Odin was intrinsically connected to death itself. In the

Ynglingsaga it is stated, “at times [Odin] would call to life dead men out of the ground, or he would sit down under men that were hanged. On this account he was called the Lord of Ghouls or of the Hanged.”

25 Odin is related in function to a psychopomp, as he receives the souls of dead warriors into his “hall of the chosen,” Valhalla. His hall is distinguished from those of the other gods by a unique and foreboding display, as Gerstein notes: “The putrefying corpse of a

varg on the gallows is the emblem of Odin’s power and the sign of his presence.”

26 She then quotes the passage of the “Grímnismál” which states, “Odin’s hall is easy to recognize: a

varg hangs before the western door, an eagle droops above.”

27Vikernes often now downplays his former interest in Satanism by claiming that Odin himself is the “adversary” of the Christian God, and therefore can be seen as Satanic. He points out that after the conversion, the old heathen gods of the North were demonized by the Christian missionaries and leaders. In this he is correct, and a perfect example survives in the “renunciation oath” which was enforced under Boniface among the Saxons and Thuringians, who were ordered to repeat: “I forsake all the Devil’s works and words, and Thunær [Thor] and Woden [Odin] and Saxnôt [the tribal deity of the Saxons] and all the monsters who are their companions.”

28In contrast to the historical precedent where the old heathen gods were transmogrified into Satanic monsters and demons, many of the denizens of Black Metal music pledged allegiance to these same demonic spirits of Christianity, only later to recast them as heathen forces. Even so, much of the culture of Black Metal will always remain rooted in concepts of the Devil and Satanism. In order to fully understand why a music genre could help to spawn as much vehemently anti-Christian destruction as has been linked to Black Metal, one must also explore its starting point in the realm of the diabolical.