6

Game Changing: Shaping the Deal/No-Deal Balance*

Beyond “zooming out” to a larger strategic concept and adopting a realistic stance, Kissinger counsels negotiators to embrace what we call a “wide-angle” view of the process that seeks sources of influence that may reach well beyond persuasive arguments in the conference room. In Kissinger’s words, as a negotiator, “you are trying to affect the conclusions of the other side, and you are trying to find something that both sides find sufficiently in their interest to adopt. That’s the essence of negotiation. . . . [I]n an international negotiation, the panoply of pressures and incentives that you can marshal is crucial.”1 The idea is to tilt the deal/no-deal balance in favor of a target agreement.

To identify potential incentives and pressures that could “affect the conclusions of the other side,” Kissinger often looks for moves outside the negotiation at hand, or “away from the table.” Faced with a reluctant counterpart to whom “no” looks superior to “yes,” Kissinger often changes the game to induce agreement. Instead of drawing a circle around yourself and your direct counterpart and simply defining your interaction as two-sided, change the game. This can mean involving or excluding parties, altering the set of issues under consideration, and/or enhancing your own no-deal option or worsening that of the other side. More conventional negotiators often focus on directly persuading a counterpart; by contrast, Kissinger often reshapes the negotiating setup itself in order to enhance the value of agreement, raise the costs of impasse, or both.

Recall the Rhodesian case study (in chapters 1–3), in which Kissinger diagnosed the fundamental reason that even the British prime minister twice failed to negotiate successfully, mano a mano, black-majority rule with Ian Smith on the decks of two British warships. Implicitly, the prime minister equated “negotiation” with the interpersonal dealings between two parties. The plain, realistic reason for the British failure: to Smith, a “no” to the British demand maintained at least some chance of preserving white power and privilege, while a “yes” meant that Rhodesian whites would soon be subordinate to blacks in that country.

Given this diagnosis, Kissinger was able to elicit a “yes” from Smith by changing the negotiating game itself to tilt the deal/no-deal balance toward the American’s preferred agreement. Kissinger undertook complex coalitional moves away from his ultimate meeting with Smith. He actively brought Britain, Tanzania, Zambia, other OAU states, and South Africa into the process in a manner that resulted in putting decisive South African pressure on Rhodesia. While giving key transitional political and economic reassurances to whites, Kissinger deployed an empathetic yet assertive style in dealing with Vorster and, especially, Smith. Within a few months, Smith’s blunt declaration that black-majority rule would not come to Rhodesia for “a thousand years” was transformed into black-majority rule “within two years.”

The inseparability of negotiation and consequences via game-changing moves will seem self-evident to many people. Yet, while there are important exceptions, nowhere does Kissinger’s approach to negotiation differ more from much current scholarship on the subject.2 This is especially true for research based on laboratory experiments in well-specified setups whose elements (e.g., the parties, issues, walkaway alternatives), by design, cannot be changed by the subjects/participants. Modern behavioral investigations into negotiation tend to focus almost exclusively on the effects on negotiated outcomes of varying one at-the-table factor at a time, while holding all else constant. Such factors might include the number of issues, the time limits, ultimatums versus an offer-counteroffer dynamic, the patterns of concession, and the attributes of the negotiators (e.g., competitive or cooperative orientation, national culture, gender).3 In a fairly typical academic view, the first editor of Harvard’s Negotiation Journal, a distinguished psychologist, characterized negotiation “as the settlement of differences and the waging of conflict through verbal exchange”[emphasis supplied].4

Kissinger stresses the narrowness and practical limitations of this view. “Historically, negotiators have rarely relied exclusively on the persuasiveness of the argument,” he averred. “A country’s bargaining position has traditionally depended not only on the logic of its proposals but also on the penalties it could exact for the other side’s failure to agree.”5 For Kissinger, artificially separating actions at and away from the table is almost analytically, and practically, incoherent: “One fundamental principle that I have learned in diplomacy is you cannot separate diplomacy from the consequences of action. The idea that you can have a diplomacy that is conducted like a graduate seminar without the rewards and penalties that attach to actions, it’s a fantasy.”6

The Special Case of Changing the Game via Coercive Moves

While changing the game can involve many elements such as parties, issues, and no-deal alternatives, Kissinger pays special attention to the close relationship of force and negotiation. In The Necessity for Choice, he notes that “Even at the Congress of Vienna, long considered the model diplomatic conference, the settlement which maintained the peace of Europe for a century, was not achieved without the threat of war.”7

In Kissinger’s experience, an overly narrow view of negotiation, as a purely verbal exchange, extends well beyond the academy: “The prevalent view within the American body politic sees military force and diplomacy as distinct, in essence separate, phases of action. Military action is viewed as occasionally creating the conditions for negotiations, but once negotiations begin, they are seen as being propelled by their own internal logic.”8

Elaborating this general point, Kissinger goes on to highlight how, in his view, this common fallacy (of separating negotiation from incentives) has worked against the effectiveness of many U.S. negotiations in practice: “[I]n America, we found it very hard to understand this . . . because we tend to present diplomacy as there’s a period of pressure and then there’s a period of negotiation, and they’re separate. . . . So in the Korean War, we stopped military operations at the beginning of negotiations. . . . So therefore you remove one of the incentives.”9

While a military pause during negotiation, in the form of a bombing halt or cease-fire, does temporarily remove an incentive for the other side to agree, it can make sense for other reasons. It can lend credibility to your willingness to call a halt to violence if a final agreement is reached, while giving the other side a taste of peace. It may strengthen a pro-deal faction on the other side or mollify one of your key domestic constituencies. Also, it may simply be the right thing to do for ethical reasons, such as damaging effects on civilians. Of course, Kissinger is often right: a pause may simply provide breathing space for one or both sides to rearm, recruit allies, and regroup.

With respect to Kissinger’s larger point about the relationship between force and negotiation, it would be hard today to find many professionals who see force and diplomacy as separate and opposite activities. The vast majority of senior officials in U.S. career services and among political appointees holds the belief that diplomacy and negotiations are most effective when joined with other instruments of national power, including economic sanctions as well as the threat and use of force. While maintaining the key role of game-changing moves, Kissinger warns bargainers not to crudely deploy sticks and carrots to influence behavior: “you have to be careful not to marshal [them] in such a way that it looks like a demand for surrender, because then you are creating an additional incentive for resistance.”10 He broadened this point in a 2016 interview: “Diplomacy and power are not discrete activities. They are linked, though not in the sense that each time negotiations stall, you resort to force. It simply means that the opposite number in a negotiation needs to know there is a breaking point at which you will attempt to impose your will. Otherwise, there will be a deadlock or a diplomatic defeat.”11

Once coercion and negotiation are explicitly linked, however, two sets of questions immediately arise. First, under what conditions are coercive measures effective as part of a negotiating strategy? Second, even if potentially effective, under what conditions are coercive moves ethical? We highlight these issues as they arise in Kissinger’s negotiations, especially with respect to military action in Vietnam and Cambodia, which we will soon examine in some depth. With the Indochina (i.e., Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) example in mind, we will revisit this important topic more fully in a separate section at the end of this chapter, “Force and Diplomacy: Considerations of Ethics and Effectiveness.”

While moves to worsen the other side’s no-deal options may involve military force, such cases are extreme; most negotiations do not involve B-52s. Rather, if the other side won’t agree, more normal consequences include economic costs, competitive disadvantages, or legal risks. No-deal can mean forging a countervailing alliance or giving a huge order to an alternative supplier. And, of course, while it is preferable to have an attractive no-deal option, sometimes your no-deal option is poor. This can give an edge to your counterpart—unless you can change the game by improving your walkaway and/or worsening theirs. Analytically, however, the core point remains: effective negotiation often involves both words at the table and deeds away from it.

Lessons from the Vietnam Negotiations

What can we learn from a reexamination of Kissinger’s arduous talks that produced the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973? After all, this agreement scarcely lasted two years before North Vietnam conquered the South. We are neither historians nor experts on this war; nor are we likely to add to the controversial “lessons of Vietnam” (a phrase that turns up no fewer than 184,000 times in a 2017 Google search).

Despite these limitations, we see taking a fresh look at the Vietnam negotiations as worthwhile because, first, they represent a challenging case of how to strengthen a weak bargaining position; second, they highlight the potential role of creative game-changing moves in such situations, including the ethics and effectiveness of coercive actions; and third, they underscore how even highly skillful negotiation ultimately depends for success on the quality of basic assumptions about the situation.

It may surprise some readers that we will characterize Kissinger’s early bargaining position with the North Vietnamese as weak. After explaining this judgment, we focus on the complex of actions that he took (often not obvious and often away from the table) to transform a poor hand into a better one. Military action certainly mattered, but so did other, less familiar factors that suggest a fairly creative approach to very tough negotiations. In various forms, this challenge of bargaining from weakness is common, important, and difficult. All things considered, despite the pain of revisiting Vietnam and the ultimate failure of the Paris Peace Accords, a fresh look can yield worthwhile insights.

Background to the Vietnam War

Countless books have been written about the polarizing war in Vietnam; the full story and its implications are complex and fraught with enduring disagreements.12 Rather than enter this debate or seek to be at all comprehensive, we will try to offer essential context and highlight aspects of the Vietnam saga that are most relevant to our focus on game-changing moves in the negotiations.13

Occupied by Japan during the Second World War, Indochina had been a French colony of some forty-two million people. With postwar Vietnam back nominally under French rule, Communist guerrillas waged an anticolonial struggle for independence with support from Communist China.

After the onset of the Korean War in 1950 and following discussions of what came to be known as the “domino theory,” President Harry Truman began aiding France in the war in Indochina. In the context of the Cold War, this theory suggested that once one country fell under Communist control, other “dominoes” in the region would fall and communism would spread. The implication was that the expansion of Communist influence had to be resisted even in areas that did not otherwise have significant strategic importance to the United States. Following its defeat at Dien Bien Phu, France withdrew from Vietnam with the signing of the July 20, 1954, Geneva Accords, which divided the country at the seventeenth parallel into northern and southern entities.14 (In fact, given the Soviet and Chinese Communist threats of that era, Truman and his successors were not wrong to worry about the aggressive campaigns of both Communist powers to undermine existing democracies and to sow divisions in the West. The issue for Indochina, however, was whether the domino theory was applicable.) Worried by the French defeat, the United States effectively recognized South Vietnam in 1955. By the end of its term, the Eisenhower administration had provided over a billion dollars in assistance, with 692 U.S. “military advisors” helping to train the South Vietnamese Army.15 Seeking to contain the spread of communism, then the guiding principle of U.S. foreign policy, President John F. Kennedy increased the U.S. presence in Vietnam from 900 to 16,263 military advisors.16 By 1963, South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem, whose policies clashed with Washington’s preferences, had been deposed and killed in a coup that the United States at least passively condoned. General Nguyen Van Thieu, one of the coup leaders, became president of South Vietnam in 1967, and remained in that position throughout the Nixon years.17

Following John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson was elected president in 1964 in a landslide. Continuing to espouse the domino theory, Johnson’s defense secretary, Robert McNamara, articulated a common view among American policy makers: “Hanoi’s victory [in South Vietnam] would be a first step toward eventual Chinese hegemony over the two Vietnams and Southeast Asia and toward exploitation of the new [wars of liberation] strategy in other parts of the world.”18

In August 1964, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution after the North Vietnamese were said to have attacked two American destroyers. Later the subject of controversy over the accuracy of reports about the attack, including whether it even happened, the Tonkin Resolution authorized President Johnson to use force to repel aggression and, in effect, to dramatically expand the war in Indochina.19

The Soviet and Chinese Connections

Although the U.S. public and policymaking community had generally regarded Communist countries as monolithic during the 1950s and ’60s, relations between the USSR and China had become increasingly tense through the 1960s. This “Sino-Soviet split” generally worked in Hanoi’s favor as the Soviet Union and China competed to be North Vietnam’s primary supporter.20 For a decade after the French defeat in 1954, China provided Hanoi with an estimated $670 million in aid, and increased support from $110 million in 1965 to $225 million in 1967. China’s aid averaged between $150 and $200 million per year during the remaining years of the war.21

After the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was passed, Chinese premier Mao Zedong personally assured Ho Chi Minh, North Vietnam’s leader, of China’s support. From 1965 to 1969, Beijing is estimated to have sent 320,000 personnel to Vietnam to help operate military equipment and to build and repair transportation links.22

The Soviet Union’s support (estimated at $365 million from 1954 to 1964) was more modest than Beijing’s, reflecting Soviet general secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s belief that Indochina was a low strategic priority compared to postwar German issues and the emerging China challenge.23 Leonid Brezhnev’s assumption of power in October 1964 marked a change in Moscow’s approach.24 As the Sino-Soviet split deepened, it became “critically important [for Moscow] to reverse the pro-Chinese trend in Hanoi.”25 Embroiling the United States in a protracted, divisive struggle that drained its resources was an added advantage that the Soviet leadership sought to exploit.26

In 1965, Hanoi rejected Chinese premier Zhou Enlai’s request that North Vietnam dissociate itself from Moscow, and accepted some $550 million in Soviet military assistance.27 In short, North Vietnam was able to secure substantial support from both the Soviets and Chinese. The forces deployed against South Vietnam included North Vietnamese troops and the Vietcong, a closely allied force of guerrillas and some regular army units, based mostly in the South.28

That same year, reassured of continued Soviet and Chinese support, Vietcong forces attacked an American air base near the South Vietnamese city of Pleiku, killing 8 Americans and wounding 126 more.29 This led President Lyndon Johnson to order the rapidly intensifying “Rolling Thunder” bombing campaign, which began in March 1965 and included targets in North Vietnam. Though smaller skirmishes involving U.S. personnel and advisors had earlier taken place, Rolling Thunder marked the beginning of major direct U.S. military engagement. Later that month, the first U.S. combat troops, consisting of 3,500 marines, landed in Vietnam.30 American involvement escalated rapidly: by the end of 1965, U.S. military forces exceeded 180,000. Over the next two years, the totals exceeded 385,000 and 485,000, respectively, growing to 536,100 U.S. troops deployed in Vietnam by 1968.31

On January 30, 1968, the Vietnamese New Year, or Tet, North Vietnamese and Vietcong troops launched massive surprise attacks throughout South Vietnam. These forces captured several cities, including Hué, Vietnam’s ancient imperial capital. They assaulted targets ranging from military command centers to the U.S. embassy in Saigon, which Vietcong troops briefly occupied. Over the next month, American and South Vietnamese forces beat back the attacks, inflicting heavy losses on North Vietnamese and Vietcong forces during what became known as the Tet Offensive.

Despite the adverse military outcome for the North and the Vietcong, the Tet Offensive shocked U.S. political and defense officials, many of whom had judged the enemy incapable of mounting such an ambitious operation. More important, it stunned the American public, which generally believed that the war was being won. CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite, widely regarded as “the most trusted man in America,” exclaimed, “What the hell is going on? I thought we were winning the war.” While a clear military defeat for the North, the Tet Offensive proved to be a great symbolic and political victory. It became the turning point in U.S. attitudes toward the war, decisively shifting the objective from winning the war militarily to finding an acceptable way out.32

Increasing waves of domestic antiwar protests had accompanied the escalation of the U.S. military role in Vietnam.33 Frustrated by his inability to bring the conflict to an end and facing a huge domestic backlash against the war, President Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek reelection. Though the Vietnam War had claimed one U.S. presidency, Johnson actively pursued negotiations with the North Vietnamese, which included a bombing halt and offers of economic aid. These talks apparently came very close to fruition, but ultimately failed (likely due to interference by then-candidate Nixon, who evidently persuaded the South Vietnamese to reject the deal since they would get better terms under his administration).34

The New Nixon Administration: Interests and Target Agreement

It is important to understand that, especially given the U.S. domestic situation, neither Richard Nixon nor Henry Kissinger believed that the Vietnam War could now be won militarily in the manner sought by previous administrations. As a candidate, Nixon promised that the “first priority foreign policy objective of our next Administration will be to bring an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.”35 Elsewhere, he bluntly articulated one of the “fundamental premises” with which he began his presidency: on Vietnam, “total military victory was no longer possible.”36 In 1968, Kissinger wrote, “The Tet Offensive marked the watershed of the American effort. Henceforth, no matter how effective our actions, the prevalent strategy could no longer achieve its objectives within a period or with force levels politically acceptable to the American people.”37 Not surprisingly, both men early on focused on finding a negotiated solution.

An Overview of Key Parties’ Interests

American and South Vietnamese Interests

Making sense of the negotiations that followed calls for at least a basic understanding of how each side saw its most important interests. Inspired by the “lessons of Munich” and the domino theory, American policy makers during the 1950s and ’60s had envisioned the Vietnam War primarily as part of a larger global pattern of Soviet- and Chinese-sponsored Communist aggression. When the Nixon administration took office, China and the USSR continued to support the North Vietnamese and Vietcong against the South. Yet, although outside Communist patrons played important roles, the war was increasingly seen as being fought among and between the Vietnamese themselves.

Given this understanding and the vanishing U.S. prospects for winning the war militarily, Nixon and Kissinger had shifted from the earlier goal of outright victory. They identified several key U.S. interests: to give the anticommunist South Vietnamese a solid chance to fend off the North militarily, to let the different Vietnam parties determine their own political fate more or less peacefully, to withdraw American troops from Indochina, and to bring home U.S. prisoners of war. These interests would be served by a withdrawal of North Vietnamese forces from the South and incorporation of the Vietcong into a peaceful political process.

More broadly, from the outset of the Nixon administration, the divisive Vietnam War had dominated U.S. foreign policy and interfered with the United States’ larger geopolitical goals, principally détente with the Soviet Union and rapprochement with China. Ending American involvement in this bloody war would enable more effective diplomacy on other, more strategically critical fronts. Yet Nixon and Kissinger were determined that Vietnam should be handled in a way that maintained the credibility of U.S. security commitments worldwide.

The Thieu regime in South Vietnam clearly saw its core interest in retaining power by preventing a takeover by the powerful North and the Vietcong. From its viewpoint, this would require the withdrawal of North Vietnamese forces from the South and continued American military involvement at a significant level. This latter preference would conflict with the U.S. interest in its forces returning home. Yet, in a critical respect, Thieu’s interests dovetailed with Kissinger’s conviction that abandoning South Vietnam, an ally of the United States through four presidencies, both was wrong in itself and would irreparably damage U.S. prestige and credibility across the globe. Indeed, Kissinger emphasized the extent to which countries ranging from Germany and the NATO allies to Japan and South Korea depended for their security on belief in American promises.38

Kissinger was especially concerned that rapidly withdrawing from Vietnam and in effect abandoning Saigon would damage Chinese respect for American power. The prospect of countervailing American force was a major factor that led China, facing a threatening Soviet Union massing troops on its border, to seek rapprochement with the United States. “Peking had no interest in a demonstration that the United States was prepared to dump its friends,” Kissinger stated; “in its long-range perspective of seeking a counterweight to the Soviet Union, Peking in fact had a stake in our reputation for reliability.”39

North Vietnamese and Vietcong Interests

For decades, North Vietnamese and Vietcong interests had included expelling foreigners (Chinese, French, and then American) from Vietnamese territory. By the time Nixon and Kissinger took power, the prime interest of the North was to ensure the withdrawal of American forces, while leaving its own forces in position. In tandem with the Vietcong guerrillas, it sought to take over the remaining noncommunist parts of South Vietnam.

In its December 31, 1968, message, Hanoi called for the “replacement of . . . the ‘Thieu-Ky-Huong’ clique,” the disparaging epithet by which the North Vietnamese regularly referred to South Vietnam’s leadership.40 At one point, North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho helpfully advised Kissinger that South Vietnamese president Thieu did not have to be removed publicly; it could be done secretly—for example, through assassination.41

The strength of the opposing North Vietnamese versus American interests on this issue, in overthrowing versus maintaining the Saigon government in the South, can be gauged from Kissinger’s unequivocal declaration on this point. He stated that “our refusal to overthrow an allied government [in Saigon] remained the single and crucial issue that deadlocked all negotiation until October 8, 1972, when Hanoi withdrew the demand.42 The North Vietnamese foreign minister explicitly and emphatically corroborated this point from his government’s viewpoint.43

As later events underscored, the North wanted to impose a Communist form of government throughout the (unified) country. While a North Vietnamese and Vietcong victory would have pleased their Soviet and Chinese patrons, the Vietnamese combatants’ focus was on Indochina, not mainly on the advance of global communism.

In this context, Nixon and Kissinger sought to negotiate an agreement with the North Vietnamese that would see all sides withdraw their forces from the South with the political future of the South determined peacefully by the key Vietnamese parties—and with American prisoners of war brought home. This had to be done in a manner that preserved the credibility of American foreign policy commitments. As should be evident even from this cursory examination of the interests of the major parties to the conflict, this would prove to be a tough sell.

As we launch into an analysis of the Vietnam talks, we step back briefly to emphasize a point that is basic to any effective negotiation: an accurate assessment of your interests. It drives the target agreement you seek to reach and often influences your strategy and tactics. If the assumptions underlying your interest assessment are deeply flawed, even a superb negotiation strategy and tactical brilliance cannot be truly successful. For purposes of the negotiation analysis that follows, we provisionally take as givens the American interests and target agreement as they were expressed at the time. Toward the end of this chapter, we revisit the assumptions underlying Kissinger’s conception of the American interests at stake in this conflict.

Negotiations Begin

On December 20, 1968, soon after Richard Nixon’s election, but before he took office, his incoming administration expressed readiness to negotiate.44 While there were numerous detailed military and political issues, the essential questions involved the terms of a cease-fire and bombing halt, the extent and timing of North Vietnamese and American troop withdrawals from the South,45 the fate of prisoners of war, and the basis for a settlement between Saigon and the Vietcong on the political future of the South. On May 14, 1969, in his first televised speech on Vietnam, Nixon presented an eight-point peace proposal, the central feature of which was a mutual pullout of each side’s forces within a year (at least the “major portions” of U.S. and allied forces46).

The North Vietnamese and Vietcong remained steady with their ultimatum: all U.S. forces had to leave Vietnam, and the United States had to depose the South Vietnamese government, with which it was allied.47 Nixon and Kissinger refused, judging that acceding to Hanoi’s demands would not only betray an ally but also deal a severe blow to U.S. credibility worldwide, putting other crucial foreign policy objectives at risk.

While inconclusive public talks (among the Americans, the North and South Vietnamese, and the Vietcong) took place in Paris, Kissinger met and negotiated secretly with his North Vietnamese counterpart, Le Duc Tho. Kissinger judged that private talks could not be used for North Vietnamese propaganda and that any willingness to settle on the part of the North would more likely be revealed in secret talks.48 (Later, and especially in chapter 13 we further explore the ramifications of secrecy in these and other negotiations.) Beginning on February 20, 1970, Kissinger and Tho met three times through April 4, 1970. During the last of these sessions, Kissinger proposed a mutual U.S.–North Vietnamese withdrawal from South Vietnam on a precise schedule over sixteen months.49 Le Duc Tho turned down this proposal.

In March 1969, Nixon had ordered the launch of a U.S. secret bombing campaign against North Vietnamese sanctuaries and supply lines in Cambodia. On April 20, 1970, partly to shore up public support for the war, and in line with his campaign pledge to end the war, Nixon announced the withdrawal of one hundred fifty thousand Americans from Vietnam within a year. Ten days later, he announced a ground “incursion” into Cambodia, consisting of tens of thousands of American and South Vietnamese troops. With public revelation of this escalation into a formally neutral country, ongoing demonstrations against the war mounted to a tidal wave of protest that washed over the United States. At Ohio’s Kent State University, on May 4, 1970, National Guardsmen shot and killed four unarmed protesting students, further convulsing the country. On May 8, almost a hundred thousand marchers converged on the White House.50 Events and proposals moved more quickly. On June 24, the Senate repealed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, though the House did not follow suit.

Hanoi, unmoved by various American proposals during this period, continued to insist that the United States withdraw its forces and effect regime change in Saigon. During 1970, the war continued to rage, with more than 6,100 American deaths in Vietnam during that single year (and many times that number of Vietnamese war fatalities). For comparison, total American deaths in Iraq during the seven years between 2003 and 2010 were 4,424.51

Barriers to Agreement

Why were these talks stuck? From a realistic perspective (evaluating the deal/no-deal balance), it is hardly surprising that these negotiations and subsequent talks went nowhere for some time. Consider three related factors—we might call them barriers to agreement—influencing how North Vietnam weighed accepting American proposals relative to saying no, stonewalling, and continuing to fight:

- In August 1965, 61 percent of Americans believed that the United States was right in sending troops to fight in Vietnam. That belief had dwindled to 41 percent by the time Lyndon Johnson announced on March 31, 1968, that he would not seek a second presidential term, due largely to the unpopular Vietnam War. By May 1971, this figure had dropped to 28 percent, meaning that 72 percent of the public thought that sending U.S. troops had been a mistake (although public support for Nixon’s Vietnam policies were significantly higher).52

- Domestic pressures rapidly mounted on the new Nixon administration to withdraw. Numerous public and congressional critics had been demanding prompt disengagement from Vietnam in return only for the release of American prisoners of war. On October 15, 1969, massive demonstrations took place around the country—twenty thousand strong in New York, thirty thousand in New Haven, and one hundred thousand in Boston (where a skywriting plane drew a huge peace sign overhead).53 The Cambodian incursion in May 1970 triggered even more intense protests. In 1971, Congress passed seventy-two (nonbinding) resolutions demanding U.S. withdrawal.54 These pressures continued to escalate, as did international condemnation of the U.S. role.

- Responding to public opposition, protests, and Congressional actions—in large part to shore up public support for its Vietnam policies and given its campaign promise to extricate the United States from Vietnam—the Nixon administration unilaterally withdrew American forces at a strikingly rapid pace. From approximately 536,000 American troops in Vietnam in 1968, when Nixon won the presidency, the total force level dropped by 70 percent, to about 157,000 troops by 1971, and to fewer than 25,000 in 1972.55

Given these factors, what incentive did a militarily confident Hanoi conceivably have to agree during those first years of negotiation, in light of its relatively appealing no-deal alternative: a fast-diminishing American military presence linked to mounting public and congressional opposition? The North Vietnamese, Kissinger observed, “coolly analyzed the withdrawal [of U.S. troops], weighing its psychological benefits to us in terms of enhanced staying power against the decline in military effectiveness represented by a shrinking number of American forces. Hanoi kept up incessant pressure for the largest possible withdrawal in the shortest possible time. The more automatic our withdrawal, the less useful it was as a bargaining weapon; [our] demand for mutual withdrawal grew hollow as our unilateral withdrawal accelerated.”56

Given this situation, Le Duc Tho “tormented” Kissinger with the seemingly unanswerable military question: “Before, there were over a million U.S. and puppet [South Vietnamese] troops, and you failed. How can you succeed when you let the puppet troops do the fighting? Now, with only U.S. [air] support, how can you win?”57 Kissinger’s evaluation of the early years of the negotiation was bluntly realistic: the North Vietnamese would draw out the negotiations while seeking a military victory.58

Recall the September 1971 image of U.S. Army general Vernon Walters hearing Le Duc Tho say to Kissinger, “I really don’t know why I am negotiating anything with you. I have just spent several hours with Senator [George] McGovern and your opposition will force you to give me what I want.”59

Kissinger’s assessment: “To them [the North Vietnamese] the Paris talks were not a device for settlement but an instrument of political warfare. They were a weapon to exhaust us psychologically, to split us from our South Vietnamese ally, and to divide our public opinion through vague hints of solutions just out of reach because of the foolishness or obduracy of our government.”60 He concluded: “No negotiator, least of all the hard-boiled revolutionaries from Hanoi, will settle so long as he knows that his opposite number will be prevented from sticking to a position by constantly escalating domestic pressures.”61

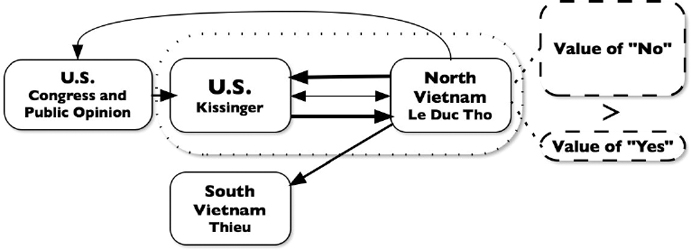

Figure 6.1 offers a highly simplified description of one core barrier to an acceptable agreement. In the figure, the two-headed arrow shows the direct U.S.–North Vietnamese negotiations; the single-headed arrows indicate one party exerting pressure on another, whether political, public relations, diplomatic, or military. The relative sizes of the two rounded figures to the right of “North Vietnam” suggest the fundamental and seemingly obvious implication: for Hanoi in 1970, “no” powerfully dominated “yes.” If this observation is accurate, just what approaches to this negotiation might Kissinger (and Nixon) have adopted that could conceivably have borne fruit in such unpromising circumstances, which we have characterized as “negotiating from a weak position”?

Figure 6.1: Fundamental Barrier, 1970–

North Vietnam Strongly Prefers “No” to “Yes”

Note: Two-headed arrows imply direct negotiations; single-headed arrows imply pressure (political, PR, diplomatic, military).

Along with President Nixon, Kissinger confronted three broad challenges as he sought to transform a North Vietnamese “no” into an acceptable “yes” that would end the war, at least for the United States:

- First, he would have to overcome unrelenting military efforts by the North Vietnamese and Vietcong to vanquish South Vietnam, persuading Hanoi that genuine negotiations leading to an acceptable deal were in its interest relative to no-deal options—despite the rapidly diminishing U.S. military presence.

- Second, he would somehow have to respond to increasingly insistent pressure from the Congress and domestic antiwar protesters to withdraw entirely and unilaterally from Indochina.

- Third, for any U.S.-Hanoi agreement short of the military victory the South Vietnamese fervently pursued, Kissinger would have to persuade a most reluctant South Vietnamese president Thieu to accept it.

In confronting these challenges, one can imagine trying different negotiation styles or venues. Would a cooperative or competitive orientation toward Le Duc Tho be best? Greater cultural understanding and sensitivity? An exquisitely tuned ability to listen to Tho, read his body language, or formulate genuinely creative options? Tune up the persuasiveness and charm of American rhetoric? Even listing these various tactical and process options should make clear how inadequate they would likely be in the face of the barriers to agreement we have identified. So, what might work?

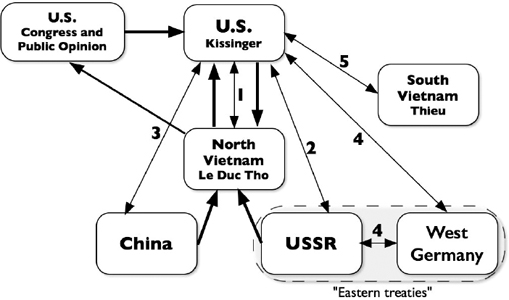

Nixon and Kissinger’s actions to surmount these barriers, to transform a weak hand into a stronger one, can be analyzed as a “negotiation campaign.”62 When we speak of a negotiation campaign, as we briefly did in analyzing the Rhodesian talks, we have in mind a target agreement—in this case, getting Le Duc Tho to say yes to an acceptable deal. (Although, if he did, further tough negotiations would be required with the South Vietnamese.) Mapping backward from that target “yes” will typically involve highlighting a required series of other agreements and actions on multiple fronts, thus maximizing, once those other agreements are in place, the chances of realizing the target agreement. As we will soon see, direct negotiations with Le Duc Tho (the North Vietnamese front) would be inadequate for success. Beyond these direct talks, Kissinger and Nixon changed the game by altering the parties, the issues, and the consequences of impasse. A simplified listing of these other campaign fronts that had been put in place by 1973 would include:63 the military contest with the North Vietnamese and Vietcong that came to involve neighboring Cambodia and Laos; U.S. domestic and congressional opinion; the Chinese; the Soviet Union; West Germany and other European countries; and President Thieu of South Vietnam.

Yet, before analyzing this multifront negotiation campaign designed to strengthen an arguably weak hand, we pose a more basic question—especially in the face of such daunting barriers to agreement that had already claimed one president, convulsed the country, and led to militarily questionable withdrawals of U.S. forces. Instead of negotiating from this unpromising position in the hope of achieving a more ambitious deal, would it have been wiser for Kissinger and Nixon to have sought an earlier agreement (say, in 1969) that would simply have provided for the return of American prisoners of war and permitted a U.S. exit from the conflict?

This question is especially apt given that, scarcely two years after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, South Vietnam fell to the North. Agreeing earlier to the same ultimate result would, to a first approximation, have saved many of the tens of thousands of lives lost between 1969 and 1973.64 After analyzing the actual negotiations, we return to this pointed question toward the end of this chapter in a separate section entitled “Underlying Judgments: Why Not Simply Withdraw from Vietnam in 1969?”

Negotiating, Responding Militarily, and Seeking Domestic Support

Prior to our analysis of barriers to negotiated agreement, we recounted the Nixon administration’s military and diplomatic actions through the May 1970 Cambodian “incursion” (“invasion” to critics). Both Nixon and Kissinger had become convinced that a strong military response to North Vietnam was required. In Kissinger’s words, “An enemy determined on protracted struggle could only be brought to compromise by being confronted by insuperable obstacles on the ground.”65 In the language we’ve been using, to make a deal more appealing to Hanoi, military action was intended to make no-deal worse. However, if such actions were seen mainly as escalating and expanding the war, they would trigger powerful protests and cost vital domestic support.

Partly on the merits and partly to maintain adequate public backing for their Vietnam policies, Nixon and Kissinger pursued three related sets of actions. First, as we have indicated, they rapidly accelerated U.S. troop withdrawals. Second, as U.S. troops went home, the fighting shifted from American ground forces to the South Vietnamese army, increasingly backed by American air and naval power (which involved comparatively few Americans and did not “count” against troop ceilings). Dubbed “Vietnamization,” this policy shift required a rapid increase in the size and training of South Vietnam’s army.66 Third, in seeking an acceptable negotiated outcome in Paris, the administration sought to “write an impeccable record of reasonableness.”67 This was intended to persuade both domestic and key foreign audiences that the United States was forthcoming in the negotiations while North Vietnam was intransigent. Being seen as flexible in negotiation would also make a tough U.S. military response more palatable if it were later required.

On September 7, 1970, in the secret Paris talks, Kissinger enhanced his earlier proposal (which Hanoi had rejected): the United States was now prepared to leave after a year (versus the prior offer of sixteen months) with no residual presence in South Vietnam (without residual forces, bases, or U.S. advisors, as the previous proposal had envisioned), provided that free and internationally supervised elections took place in the South.68

At first blush, this proposal might be seen as Kissinger making the Negotiation 101 mistake of “bidding against himself,” as the North Vietnamese had not budged before he made a better offer. Yet two factors work against this interpretation. First, a critical objective in these negotiations was to establish for domestic and other audiences (when the American concessions became public) just how reasonable and forthcoming the United States had been relative to Hanoi. Second, the American position on the ground was steadily weakening as U.S. troops rapidly withdrew; the negotiating position reflected this reality—and both sides knew it.

On October 7, in a major television speech that was generally well received, Nixon proposed a “standstill” cease-fire across Indochina, including a bombing halt, until a broader agreement could be reached. Along with troop withdrawals and increasing Vietnamization, this speech was intended in part to open up more domestic political space for stronger military action against North Vietnam and the Vietcong, which both Kissinger and Nixon expected to be necessary. Referring only to the public negotiations in Paris, Nixon positioned the United States as accommodating and persistent in seeking a negotiated settlement while accusing Hanoi of being unreasonable and uncompromising.69 Nixon kept the Kissinger-Tho talks secret, hoping that this channel might prove more promising. The North Vietnamese quickly turned down his proposals.70

The United States took much more extensive steps to cut off the Vietcong insurgency’s supply lines and sanctuaries in neighboring Cambodia and Laos. Hanoi had been using these routes and locations since the late 1950s to supply the Vietcong guerrillas and to attack and kill South Vietnamese and American troops.71 As we’ve just described, following the secret bombing that started in March 1969, thousands of U.S. and South Vietnamese troops had invaded North Vietnamese sanctuaries in Cambodia in May 1970 (which led to massive U.S. antiwar demonstrations). In January 1971, U.S. fighter-bombers launched heavy airstrikes intended to hit North Vietnamese supply camps in Laos and Cambodia. During the first few months of that year, an all-South Vietnamese force, aided by American airpower, attacked North Vietnamese positions in Laos, taking very heavy casualties and calling into serious question the effectiveness of the Vietnamization program.72

In the context of the Vietnam War, Nixon and Kissinger, along with others, saw Cambodia in particular as a key front where the North Vietnamese had been massively involved for years, independent of American actions. The Americans regarded the ground invasions and bombing of Cambodian and Laotian sanctuaries as militarily necessary to starve the Vietcong insurgency of support and to reduce Vietcong attacks on American and South Vietnamese soldiers. Kissinger indicated that within weeks of the Nixon administration’s taking office, “[t]he Vietnamese communists started an offensive that killed four to six hundred Americans a week, so that after a month we had lost more people in the Vietnamese offensive than we were to lose in 10 years of war in Afghanistan. Many of these casualties came from four North Vietnamese divisions that had occupied a part of Cambodian territory.”73 Kissinger and Nixon saw the Cambodian operations as signaling to the North Vietnamese and their patrons in Moscow and Beijing that the United States had the will and capacity to resist Hanoi.74 As Kissinger argued more broadly, “We needed a strategy that made continuation of the war seem less attractive to Hanoi than a settlement.”75

This military strategy triggered extensive domestic protests about U.S. military moves in Cambodia and Laos. Critics condemned these sometimes secret actions as militarily ineffective, democratically illegitimate, and representing an unjustified expansion of the war into neutral countries with dire long-term consequences for the region. (We revisit these critiques in a separate section toward the end of this chapter, when we explicitly examine the effectiveness and ethics of imposing costs, especially the use of force, as a means of inducing agreement in negotiation.)

In the meantime, American troop withdrawals continued. The last U.S. Marine combat units left Vietnam in April 1971, ending major marine participation in the war. In the ensuing period, Kissinger offered a series of increasingly significant concessions. While previous offers envisioned a mutual U.S.–North Vietnamese withdrawal from South Vietnam, Kissinger told Le Duc Tho on May 31, 1971, that the United States was prepared to withdraw unilaterally in return for an end to North Vietnamese infiltration of Cambodia and Laos, which at least implicitly meant leaving intact the existing Vietcong and regular North Vietnamese formations in the South.76 On August 16, he offered to withdraw U.S. troops at the same time as the prisoners were released, as long as this did not involve the United States removing Saigon’s government on the way out.77 Hanoi continued to say no.

Henry Kissinger had developed a more granular view of his consistently intransigent North Vietnamese counterpart. In later reflections, he observed that “Le Duc Tho’s profession was revolution, his vocation guerrilla warfare. He could speak eloquently of peace but it was an abstraction alien to any personal experience. He had spent ten years of his life in prisons under the French. In 1973 he showed me around an historical museum in Hanoi, which he admitted sheepishly he had never visited previously.”78

Kissinger’s assessment of Le Duc Tho and the North Vietnamese leadership he represented had straightforward implications for the negotiation approach that had a chance of succeeding: “I grew to understand that Le Duc Tho considered negotiations as another battle. Any settlement that deprived Hanoi of final victory was by definition in his eyes a ruse. He was there to wear me down. As the representative of the truth[,] he had no category for compromise. Hanoi’s proposals were put forward as the sole “logical and reasonable” for negotiations. . . . As a spokesman for the ‘truth,’ Le Duc Tho had no category for our method of negotiating; trading concessions seemed to him immoral unless a superior necessity supervened, and until that happened he was prepared to wait us out indefinitely. He seemed concerned to rank favorably in the epic pantheon of Vietnamese struggles; he could not consider as an equal this barbarian from across the sea who thought that eloquent words were a means to deflect the inexorable march of history.”79

Of course, whether it was personality or ideology that induced Le Duc Tho toward intransigence, it was also a plain fact that a North Vietnamese waiting game seemed likely to pay off given the steadily weakening American position.

As 1972 approached, however, a number of signs pointed toward a major North Vietnamese offensive that was taking shape against the South. Especially in view of his assessment of Le Duc Tho and the Hanoi regime behind him, Kissinger argued that such an offensive must be blunted in order for him to make progress in the Paris talks: “In the final analysis we cannot expect the enemy to negotiate seriously with us until he is convinced nothing can be gained by continuing the war.”80

Nixon and Kissinger sought to further prepare the diplomatic and domestic ground for the powerful U.S. military response (primarily via airpower) that they felt would be necessary to complement the South Vietnamese ground defense.81 To accomplish this, Nixon felt that he needed to greatly strengthen his administration’s public record of reasonableness in negotiations and to bring home more soldiers. Although a reduced U.S. force would be less effective in thwarting a North Vietnamese offensive, and would certainly diminish Kissinger’s bargaining leverage, Nixon continued to withdraw American troops, bringing the level down to 156,800 soldiers by the end of 1971 (from half a million only two years prior—and that total would rapidly fall to fewer than 25,000 by year’s end 1972).

At the same time, to strengthen the U.S. military posture even as troops were being withdrawn, Kissinger noted that “by early March, with a decisive [North Vietnamese] offensive clearly approaching, we found ourselves in the anomalous position of augmenting with forces that did not count against the troop ceiling—B-52s, aircraft carriers—while continuing the promised withdrawals of ground troops and planning the announcement of the next round of withdrawals, which would be expected about May 1.”82

In a January 25, 1972, address to the nation, President Nixon for the first time revealed the secret talks between Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, publicizing an eight-point peace plan. Disclosure of these talks was not unanticipated by Kissinger, who later wrote, “To be sure, our exchanges with the North Vietnamese were secret. But I always conducted them with their ultimate public impact in mind. If pressed too far, we had the option to disclose them.”83 After criticizing Hanoi for earlier rejecting the increasingly forthcoming American peace proposals, Nixon offered to withdraw the balance of U.S. troops within six months.84 However, he once again refused to overthrow the government in Saigon.85

Kissinger shared the text of Nixon’s January 25 speech with Moscow and Beijing, warning that U.S. patience with North Vietnam was running low.86 As expected, Hanoi launched a major Spring Offensive on March 30, 1972, employing as many as two hundred thousand troops in an all-out effort to vanquish South Vietnam, largely by conventional rather than guerrilla forces.

In Nixon and Kissinger’s view, this represented one last (massive) throw of the dice by North Vietnam. In Kissinger’s words, “Now, as before, we were given only one way out of the war [in the Paris negotiations]—to dismantle our ally and withdraw unconditionally. We had rejected surrender at the conference table; we would refuse it on the battlefield.”87 He continued: “I had reckoned all along that Hanoi’s offensive would culminate in a serious negotiation, whatever happened. If Hanoi were to prevail on the battlefield, Nixon would be forced to settle on Hanoi’s terms; if the offensive were halted and the probable Democratic candidate, Senator George McGovern, looked as if he was winning the election, Hanoi would wait; it would gamble on the extremely favorable terms he was offering. . . . If the offensive were blunted and Nixon looked like the probable winner, Hanoi would make a major effort to settle with us.”88

Nixon and Kissinger decided to respond forcefully to the huge Spring Offensive, by mining North Vietnam’s Haiphong harbor, thus depriving Hanoi of Soviet military supplies (especially oil) that arrived by sea. They also undertook a massive bombing campaign both of North Vietnamese forces and in North Vietnam, especially of the roads and rail lines from China, which would be the preferred alternative route for supplies.89 As the fierce fighting in the South subsided, it appeared that North Vietnam suffered more than one hundred thousand casualties and lost more than half its tanks and heavy artillery. It would take more than three years for it to regroup for its next major conventional assault on the South (which took place after the Peace Accords and succeeded in conquering the South).90 Yet, as the broader failure of its Spring Offensive sank in, Hanoi began to soften its stance in the talks.91

This U.S. campaign of bombing and mining generated major protests in the United States. Still, contrary to widespread later impressions, careful tracking of polls measuring overall public support for Nixon’s Vietnam policies shows this support starting to climb steadily from the 1972 Spring Offensive onward. At that time, support for Nixon’s policies stood at about 50 percent, then climbed through the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, when that figure approached 80 percent.92 In part, the positive public reaction was informed by two historic and widely popular U.S. diplomatic initiatives (except among many conservatives) that sandwiched North Vietnam’s Spring Offensive (launched March 1972) between President Nixon’s highly publicized trip to China to meet with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai (February 21–28) and his high-profile summit in Moscow with Leonid Brezhnev (May 22–30).

Thus far we have discussed Kissinger’s campaign for “yes” from Hanoi in terms of direct negotiation with the North Vietnamese, the use of force, and moves to manage strenuous domestic and congressional opposition (including troop withdrawals and seeming reasonableness in the Paris talks). Yet the negotiations, from an American point of view, were still stuck, though the North Vietnamese position showed signs of softening after the North’s costly 1972 offensive. How else might Kissinger strengthen his position in these talks by raising the cost of impasse to Hanoi?

Beyond direct military action to counter the North Vietnamese offensive, Nixon and Kissinger had consistently been seeking new sources of pressure on Hanoi in Paris. Specifically, they attempted to reduce or eliminate at least some of the significant diplomatic and military support for North Vietnam that Moscow and Beijing had provided. To do so, Nixon and Kissinger had consciously linked U.S. policy in Vietnam to the developing détente with Moscow and the nascent rapprochement with Beijing—which represented two additional “fronts” in the negotiation campaign. Indeed, focusing well beyond the U.S.-Hanoi “table,” Kissinger consistently stressed the priority the United States attached to obtaining Soviet and Chinese help with the Vietnam negotiations. “Every statement [we made],” Kissinger declared, “was part of an effort to persuade Moscow and Peking to acquiesce in our course and thus to move Hanoi, by isolating it, to meaningful negotiations.”93

Seeking Chinese Assistance on Vietnam

From early in the Nixon administration, Kissinger had sought better relations and an arms control agreement with the USSR. While professing interest, however, the Soviets appeared to be going slow, even stalling progress, perhaps hoping that American eagerness would produce concessions. Yet, soon after coming into office, President Nixon and Kissinger acted on a historic opportunity to explore positive relations with Beijing, hoping to overcome the U.S.-Chinese mutual hostility of the preceding years.94 Not only did better relations with China promise independent benefits for the United States, but the prospect of a closer U.S.-Chinese relationship would likely prod the Soviets into a more forthcoming approach with the United States (discussed at length in the next chapter).

This dynamic would capitalize on the deteriorating Sino-Soviet relationship, which had continued to sour since the mid-1960s, with the Soviets increasing troop numbers from twelve to forty divisions along the Sino-Soviet border.95 Not only had the rhetoric between Moscow and Beijing become more strident, but serious border clashes had broken out along the Ussuri River in 1969, with dozens killed and perhaps hundreds of casualties on each side.96

We pause for a moment to reflect on the role that luck can play in negotiation—if the potential of an unexpected opportunity is recognized and developed. Kissinger explains: “[B]y March 1969, Chinese-American relations seemed essentially frozen in the same hostility of mutual incomprehension and distrust that had characterized them for twenty years. The new Administration had a notion, but not yet a strategy, to move toward China. Policy emerges when concept encounters opportunity. Such an occasion arose when Soviet and Chinese troops clashed in the frozen Siberian tundra along a river of which none of us had ever heard. From then on ambiguity vanished, and we moved without further hesitation toward a momentous change in global diplomacy [emphasis added].”97

To move forward, it was important to signal to a suspicious China that the United States had a genuine interest in better relations. At a National Security Council meeting in August 1969, Nixon expressed the view that, given the tense circumstances between the two Communist giants, the Soviet Union was the more dangerous party and it would be against U.S. interests for China to be “smashed” in a Soviet-Chinese war. Kissinger underscored the significance of this shift: “It was a revolutionary moment in U.S. foreign policy: an American President declared that we had a strategic interest in the survival of a major communist country with which we had had no meaningful contact for twenty years and against which we had fought a war and engaged in two military confrontations.”98

Nixon and Kissinger made a major decision to the effect that, in a Sino-Soviet conflict, the United States would adopt a posture of neutrality but “tilt to the greatest extent possible toward China.”99 Various U.S. officials conveyed versions of this message in different forums. These moves were intended to dispel Mao’s fears that the United States would cooperate with the USSR against China.

Even as the United States began to interact directly with Beijing—Kissinger’s first secret visit took place in July 1971 and Nixon’s initial state visit in February 1972—Kissinger needed to confirm that China’s close links to North Vietnam would not preclude a U.S.-Chinese rapprochement. As the relationship developed, Kissinger went further: he increasingly made clear to his Chinese interlocutors that U.S.-Chinese strategic cooperation was partially linked to China’s assistance in reining in its North Vietnamese client, a point that was not lost on the Chinese. During the first meeting between Zhou Enlai and Kissinger, Zhou remarked of North Vietnam, “[W]e still feel a deep and full sympathy for them.” Kissinger noted afterward, “Sympathy, of course, was not the same as political or military support; it was a delicate way to convey that China would not become involved militarily or press us diplomatically.”100

This Chinese shift shook Hanoi. In an interview, Nguyen Co Thach, an aide to Le Duc Tho during the Paris talks and later North Vietnam’s foreign minister, strikingly characterized Chinese support of his country after Kissinger’s July 1971 trip to the Middle Kingdom: “I must say that we have realized that step by step they have reduced their support. And in ’71 we see that it is a turning point. It is not only to reduce aid, but it is a betrayal . . . after the visit of Kissinger, they advised us to accept the position of the USA. So, we see that it was . . . betrayal [emphasis added].”101

Nixon and Kissinger judged that negotiating better U.S.-Chinese relations would be intrinsically worthwhile, independent of any consequences for the Vietnam talks. Yet American diplomacy with China had three direct and indirect effects on efforts to negotiate a settlement to the Vietnam conflict. First, unlike with the Korean War, in which Chinese troops directly fought American forces, China gave tacit (and true) assurances to Kissinger that its forces would not have a combat role in Vietnam. Second, to an extent that is still debated but that certainly mattered, China moderated its material support for Hanoi and helped isolate North Vietnam diplomatically.102 Third, the threat of a developing U.S.-China axis led the Soviets to moderate their support for Hanoi.

Seeking Soviet Assistance on Vietnam

Kissinger had earlier sought to reduce U.S.-Soviet tensions through a policy of détente. While somewhat receptive, the Soviets had been playing hard to get. The surprise opening to China apparently jolted Moscow and worried the Kremlin about a possible U.S.-China alignment. Building on the developing American rapprochement with China, Kissinger turned to the Soviet front with renewed emphasis. Results were not long in coming. Kissinger noted that “Prior to my secret trip to China, Moscow had been stalling for over a year on arrangements for a summit between Brezhnev and Nixon . . . [T]hen, within a month of my visit to Beijing, the Kremlin reversed itself and invited Nixon to Moscow.”103

In this new situation, Kissinger sought to persuade the Kremlin to sharply reduce its diplomatic and military support for North Vietnam, in part by threatening Moscow with abandoning détente and risking its potential benefits.104 Kissinger calculated that the prospect of deeper détente had already built up the Soviet “stake” in the USSR’s bilateral relationship with the United States—which, Kissinger recognized, Moscow cultivated in part to counterbalance the burgeoning U.S. relationship with China. That improvement had whetted Moscow’s appetite for further progress.105

Opening a German Front to Induce Further Soviet Pressure on Hanoi

Yet how might this Soviet appetite for enhanced trade be useful with respect both to Vietnam and to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, or SALT? Kissinger saw a potential source of U.S. leverage in the United States’ ability to offer, or block, progress toward resolving the long-simmering dispute between the Soviets and the Western Allies over wartime claims and the status of Germany. This dispute had hampered Soviet efforts to expand valuable trade and diplomatic efforts, especially with Western Europe.106 Hence, Kissinger envisioned yet another front, this time a German one, in the campaign to persuade Moscow to lean on North Vietnam in its Paris talks with the United States.

The essential background: in 1969, West German prime minister Willy Brandt had begun an intensive effort (Ostpolitik), largely independent of Washington, to break the Cold War impasse with the Soviets that had persisted for years. Brandt proposed a series of treaties to reduce tensions with the USSR by opening trade agreements, resolving disputed territorial claims, and clarifying military arrangements. His initiative was motivated largely by his goal of keeping alive the dream of a unified German state (through engendering Soviet flexibility on this issue).

Brandt’s Ostpolitik would earn him the Nobel Peace Prize, but Washington had been deeply concerned that this policy might lead toward a neutral, possibly nationalist Germany. Now Kissinger realized that, in order to gain U.S. leverage on Vietnam (and arms control), it might be an opportune time to carefully soften American reservations about Brandt’s Ostpolitik, which the Soviets had eagerly sought to advance.

A tangible opportunity for such leverage flowed from the so-called Eastern treaties, which would help Moscow relax its tensions with West Germany and, more broadly, Western Europe.107 Under the Eastern treaties championed by Brandt (notably, the 1970 Treaty of Moscow between West Germany and the USSR), the signatories would normalize relations and renounce the use of military force. While West Germany and the USSR signed the Moscow treaty on August 12, 1970, Germany had not yet ratified it. Given Brandt’s somewhat shaky political situation, Moscow sought U.S. help in pressing Bonn for prompt ratification (which Kissinger linked to a separate deal on Berlin).108 In a preparatory decision memo, Kissinger’s top staff explicitly raised the option of using these issues to obtain Soviet help with the Vietnam talks.109

Privately, Kissinger doubted how effectively the United States could be in intervening in West Germany’s domestic politics. Nevertheless, seeking leverage that could lead to Soviet help on Vietnam, he took advantage of Moscow’s assumption that American support was crucial to achieving German ratification. According to the U.S. State Department Office of the Historian, shortly after Kissinger’s meeting with Brezhnev, Kissinger reported back to Nixon, “‘Brezhnev and his colleagues displayed obvious uneasiness over the outcome of the German treaties,’ he reported, ‘and made repeated pitches for our direct intervention. The results of Sunday’s election and the FDP defection have heightened their concern, and the situation gives us leverage. I made no commitment to bail them out . . . We will see to it that we give them no help on this matter so long as they don’t help on Vietnam.’”110

Beyond the China factor, economic considerations offered Kissinger considerable potential leverage. From the time of Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin through Leonid Brezhnev, increased trade with the United States in particular and the West in general became a major Soviet objective, both to boost the USSR’s sagging economy and to close a widening technological gap. A number of economists and security analysts have traced the evolution of this priority; drawing on their work, one summary concludes that “Western trade was emerging as the panacea for Brezhnev’s problems: it would revitalize the economy, allowing it to compete with [the] West; and it would do so without requiring a fundamental restructuring of the economy.”111 During 1971 and 1972, an increasing number of large trade deals (e.g., grain, trucks) between the two countries were inked, and Most Favored Nation trading status was promised to the Soviet Union, along with extensive trade credits. If détente could be made irreversible, expectations were for this trend in trade to accelerate. Soviet academic and theoretical institutes as well as the Central Committee endorsed the value of this development. Brezhnev stressed its importance in his visits to America and West Germany. He was “staking the success of his revitalization program” on stable U.S.-Soviet relations and making détente “irreversible.”112

During a conversation with Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, Kissinger accused Moscow of “complicity” in Hanoi’s March 1972 offensive against South Vietnam, and stated explicitly that Soviet support for North Vietnam now posed grave difficulties for Washington to cooperate with Moscow on the Eastern treaties.113 Lest the Soviets fail to get the seriousness of this message, Kissinger communicated the same point to Egon Bahr, Brandt’s advisor, with the expectation that Bahr would pass the message to the Soviet ambassador in Bonn.114

With respect to the talks in Paris over Vietnam, Nixon’s public revelations about American negotiating flexibility and major concessions had pointedly contrasted with North Vietnamese intransigence. This was not lost on the Soviets. On May 8, Nixon had publicly offered the North Vietnamese the most generous terms so far (while still mining the Haiphong harbor and bombing transportation links to China in response to the North Vietnamese Spring Offensive). As Kissinger described it, Nixon’s proposal offered “a standstill cease-fire, release of prisoners, and total American withdrawal within four months. The deadline for withdrawal was the shortest ever. The offer of a standstill cease-fire implied that American bombing would stop and that Hanoi could keep all the gains made in its offensive. We were pledged to withdraw totally in return for a cease-fire and return of our prisoners.”115

Kissinger used the impending May 1972 Soviet-American presidential summit in Moscow (which would include the signing of the SALT agreement) as another forcing point. Though warning Moscow about its support for Hanoi, Kissinger explicitly emphasized to the Soviet leader a major American concession he had been signaling to Le Duc Tho: the United States would not demand a complete withdrawal of the regular North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam in return for the North Vietnamese relinquishing their demand for the Americans to forcibly remove Thieu from power.116

During a presummit meeting with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in Moscow, Kissinger pointedly complained about the continued stalling tactics by the North Vietnamese and ended with a stern warning: “If this process is maintained we will act unilaterally at whatever risk to whatever relationship.”117 At one point, Kissinger told Soviet ambassador Dobrynin that “the Soviets had put themselves into the position where a miserable little country [North Vietnam] could jeopardize everything that had been negotiated for years.”118 Despite the tough talk, Kissinger himself did not think that Moscow could “halt the war by ukase [edict], or be expected to turn openly against its ally [North Vietnam].” But Moscow’s acquiescence could “ease our job.”119

On the Soviet diplomatic front, however, major progress was made. While rhetorically condemning U.S. policy in Vietnam, the Soviets did not meaningfully act in response to the massive American bombing and mining during the Spring Offensive. The Moscow Summit took place, the SALT I treaty was signed, and the USSR assumed a more restrained public posture vis-à-vis Hanoi. The absence of a significant Soviet reaction to the major American escalation in Vietnam (e.g., the summit, SALT), a real concern to many American officials, offers a measure of Kissinger’s success in his efforts to boost the importance to the Soviets of their relationship with the United States relative to their commitment to North Vietnam.

The extent of Soviet pressure on North Vietnam has been the subject of debate, but it was certainly a factor in Hanoi’s calculations. For example, Marvin and Bernard Kalb offered a relatively positive assessment: “On June 15 [1972], [Soviet] President Podgorny flew to Hanoi. The North Vietnamese, feeling betrayed by Russia’s hospitality to Nixon, were nevertheless dependent on Moscow as the chief supplier of their war matériel, and they listened carefully to Podgorny’s message. It was simple but fundamental: he suggested it was time to switch tactics, time for serious negotiations with the United States. The risk, he argued, would not be critical; after all, Nixon seemed serious about withdrawing, and the new U.S. position no longer demanded a North Vietnamese troop pullout from the [S]outh. . . . It was a new vocabulary for the Russians—the first time they had so openly committed their prestige to a resumption of negotiations. It clearly reflected the Soviet conclusion that the advantages of dealing with Washington on such matters as trade, credits, and SALT were important enough for Moscow to lend Nixon a hand in settling the Vietnam War.”120

In contrast to the Kalbs, others, such as Winston Lord (who participated in the Moscow, Beijing, and Hanoi talks with Kissinger), judged the effects of Soviet pressure on the North to be more psychological than material.121 And as just noted, Kissinger himself expected Soviet pressure to be helpful, but not decisive, in the Paris talks.

It is hard to sort out whether Soviet pressure on Hanoi resulted from the U.S. opening to China, American actions on the Soviet-German front, or the broader risk to the Soviets that benefits of détente would be lost. Opinions vary, but the implication is similar: the Kremlin, mindful of its developing relationship with America, exerted some pressure on North Vietnam to settle. For example, in the view of Georgy Arbatov, a leading Soviet expert on American politics who advised five general secretaries of the Soviet Union, “Kissinger thinks it was China that played the decisive role in getting us to feel the need to preserve our relationship with the U.S.A.” Arbatov reflected, “But Berlin actually played a much bigger role, almost a decisive one. Having the East German situation settled was most important to us, and we did not want to jeopardize that.”122

Independent of the magnitude of pressure on Hanoi that resulted from Kissinger’s actions away from the table in Beijing, Moscow, and Berlin, we pause to note how these rather creative moves were designed to improve the fairly weak hand that Kissinger was originally dealt. As game-changing moves (relative to purely at-the-table tactics in Paris), they opened new fronts in Kissinger’s negotiation campaign. The extent to which his actions on these new fronts actually furthered American objectives at the table (for which the evidence is mixed) stands as an important related question.

Breakthrough in the Paris Talks

The combination of U.S. actions on multiple fronts (blunting Hanoi’s Spring Offensive on the ground and with the bombing and mining of the North; securing Chinese agreement to moderate China’s support for North Vietnam; inducing greater Soviet cooperation as a function of the U.S.-China initiative and linked German-Soviet talks) appeared to produce the result in the Paris talks that Kissinger deemed essential. On October 8, 1972, Le Duc Tho dropped North Vietnam’s long-standing demand for the United States to force regime change in Saigon as a condition for the deal. The provisional agreement included a cease-fire, the withdrawal of American forces, cessation of North Vietnamese infiltration of South Vietnam from Laos and Cambodia, and the release of the American prisoners of war.123 Kissinger and his associates were privately jubilant at what finally appeared to be the breakthrough they had sought. Kissinger reflected, “I turned to Winston [Lord] and said ‘we’ve done it’ and shook hands with him. So it was a great moment.”124

Persuading South Vietnamese President Thieu to Agree

Expecting a turning point in the negotiations, Kissinger had kept in contact with President Nguyen Van Thieu in Saigon.125 He had not, however, revealed the full extent of American concessions to Hanoi. He indicated that Thieu “had authorized such secret talks” and that he “was kept thoroughly briefed on my secret negotiations from the beginning.”126 How fully Thieu was informed or consulted is a matter of considerable disagreement.127 In any case, Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s military assistant, briefed Thieu in Saigon on August 17 on the emerging agreement and gave him a letter of reassurance from Nixon, who pledged continued support for Saigon after the war.128 Still, it was not clear whether the South Vietnamese leader would eventually accept the agreement. In fact, Thieu was adamant in his opposition.

Almost immediately, persuading President Thieu (using both threats and assurances) to accept the negotiated outcome became Kissinger’s top priority. The threats, delivered orally and in writing, centered on the possibility of the complete cutoff of American aid in case Saigon refused to go along with the negotiated framework.129 Along with the threats, Kissinger frequently communicated Nixon’s assurances, which revolved around the president’s stated determination to stand by its ally in Saigon in response to violations of the agreement by the North Vietnamese.130

Reelected to the presidency in a November 1972 landslide against the antiwar candidate George McGovern, Nixon saw his rising political standing seem to enhance the credibility of these promises and threats. With the election, he appeared to enjoy a significant popular mandate.131 “Our thinking,” Kissinger remembered, “was that the agreement could be preserved unless the North Vietnamese launched another all-out offensive, in which case we believed that a combination of American air power and existing South Vietnamese ground forces could repeat the experience of ’72 [the successful military response by South Vietnamese forces and American airpower to the spring 1972 North Vietnamese offensive].”132

From early October until mid-November 1972, Thieu artfully postponed his acceptance of the agreement, requesting a number of changes.133 In Kissinger’s view, it was becoming increasingly clear that Saigon was not interested in any negotiated compromise, but, understandably, in keeping a major U.S. military presence in the South and ensuring a total victory over Hanoi.134