As the sun stretched across the sky on a warm June day in 2001, dozens of indigenous women began to arrive in the community of Morelia in eastern Chiapas. They came in twos and threes, each small group representing a different Zapatista village. Some had trudged for hours along dirt paths. Others stepped off a repurposed yellow school bus and shook the dust from their colorful aprons. Each woman came prepared to stay for several days, with a bundle of tostadas wrapped neatly in a clean cotton cloth.

Over a hundred Zapatista women came to Morelia for this particular gathering. Morelia is one of five Caracoles, geographic centers of Zapatista territory that house infrastructure for gatherings like this one. There was a large auditorium, a collective kitchen, and several dormitories, all made of long wooden planks, with dirt floors and corrugated tin roofs. Women had come from throughout their region, the autonomous municipality Diecisiete de Noviembre.

Micaela is a Zapatista comandanta (commander) from that region. The comandantes are the EZLN’s political leaders. Despite their military-sounding title, they are civilians and are not part of the Zapatista army. Comandanta Micaela had asked me to facilitate activities for the participants to reflect on their involvement in the Zapatista movement. Speaking about the importance of recording the women’s stories, she said, “We can’t live like we did before. Things began to change because we organized. It’s clear to us what women’s lives were like before, and how we want our lives to be now. We want respect and we want rights for women.”1

Comandanta Micaela was one of the regional coordinators who shaped my project in Chiapas. I valued the dialogue and teamwork with the Zapatista authorities who guided our work, and Micaela was one of the women I most respected and admired. A few years older than me, she and her husband had belonged to the EZLN since the late 1980s and are both still members of its political leadership today. One of the twenty-three comandantes who traveled to Mexico City as part of a Zapatista caravan in 2001, she is as comfortable speaking to large crowds as she is chopping firewood and carrying water in her village. Sitting in the Caracol or during a visit to her house, Micaela would share her thoughts about her work with women and what needed to happen to move it forward. She had helped organize this women’s gathering and we had both been looking forward to it.

Reflecting the high level of discipline within the Zapatista movement, every aspect of the women’s gathering in Morelia was well organized. Representatives had come from many different communities, rotating groups of cooks stirred massive pots of food over wood fires, and the activities began early each morning, with the roosters still crowing and mist clinging to the lush mountains that rose directly behind the auditorium. Women from the Morelia region speak Tzeltal, Tzotzil, and Tojolabal, and each group can be distinguished by their particular style of embroidered blouses and handwoven skirts. Women sat on rough-hewn wooden benches in a large circle and shared stories of hardship as well as triumph—stories of clandestine meetings with the first women insurgents, of participating in marches and protests, and of the struggle to ban alcohol in their communities and the subsequent decrease in domestic violence.

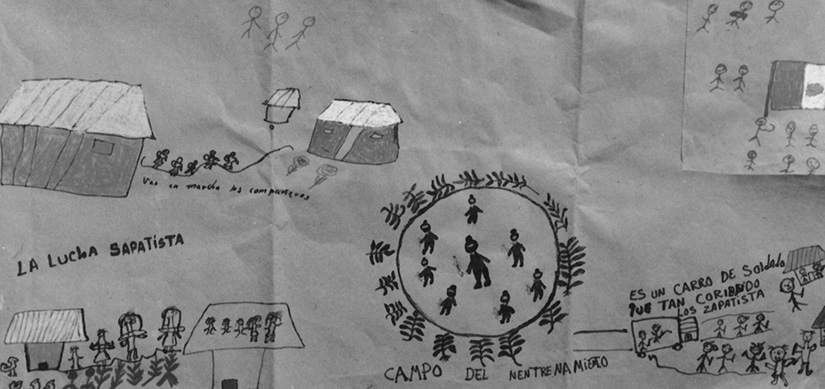

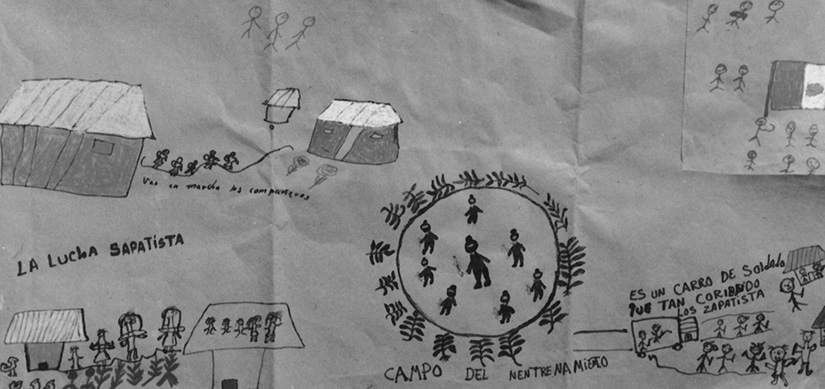

A drawing of el camino de nuestro despertar includes depictions of women leaving for a march, an insurgent training camp, and a truck full of soldiers being chased away by Zapatistas. (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)

In one activity, women divided into groups and sculpted el camino de nuestro despertar (the path to our awakening). Each group used a ball of clay supplemented by twigs, leaves, and rocks to illustrate the radical break that zapatismo represented in their journeys toward indigenous women’s empowerment. These paths were literal as well as symbolic. One group, for example, sculpted the dirt road from their houses to the women’s meeting. There were obstacles along the way, like armed Mexican soldiers made of clay with groups of women confronting them, and rocks in the path that represented not knowing how to read and write, or their husbands forbidding them to leave the house. In another exercise, the women drew a map of their region and indicated all the villages with women’s cooperatives. These cooperatives provide a measure of economic autonomy but are also an important space for women to begin to express themselves, and are an indicator of how well-organized women are in any particular village. Different drawings represented the different types of cooperatives: a brick oven for a cooperative bakery, vegetables for a collective garden, and so on. As they stepped back to look at the map, the women were visibly impressed by those villages that had multiple drawings indicating several women’s cooperatives. The conversations continued informally after the activities ended. For lunch, each woman received a bowl of beans and they chatted as they unknotted the cloth napkins that held their tostadas. After they ate, the young women played basketball while the older women sat and rested in the shade.

Throughout the three days of the gathering, the women described a series of remarkable transformations. During an activity comparing their lives now and their lives before, they explained:

Before 1994 there was no respect for women. Even our fathers told us we weren’t worth anything. We didn’t have the right to hold public responsibility. Ifwe tried to speak up in the assemblies, the men made fun of us. They insulted us and said that women didn’t know how to talk.

Thanks to our organization [the EZLN], we have opened our eyes and opened our hearts.2 It was in the organization that they first began telling us that how we were living was not right. We joined the struggle and that’s when things started to change and we stopped being oppressed. Now we can participate in political work. In community and regional assemblies we participate side by side with the men. We have the right to hold any position within our organization. We also have the right to leave the house, to dance, to sing, to play sports, to go to a community party. Today there is hope and freedom in our lives. Thanks to the organization we have found compañerismo and unity. [Compañerismo is the solidarity that comes from being compañeros.] We have also found respect between men and women. Our struggle is our liberation because it gave us the courage to participate and defend our rights.3

Especially in the years just before and after the 1994 uprising, Zapatista women experienced social changes that often take generations to unfold. Women have established their right to decide whom to marry and when, and how many children to have. There has been a notable reduction in alcohol consumption and domestic violence. Women and girls have much greater access to health care and education, and women are exercising their right to participate in public affairs. It is impossible to separate this series of transformations from women’s involvement in the Zapatista movement.

Women’s rights have been a tenet of the Zapatista movement since its inception, established by the leadership of the EZLN and made a reality by the groundswell of response from women in the communities. Since its formation, the EZLN pushed for equality within its own ranks. The Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional (National Liberation Forces, FLN) was the political-military organization that founded the EZLN. The Mexican students and urban leftists who made up the FLN insisted that women could participate at all levels of the struggle, and this commitment carried over to the EZLN. In the decades leading up to the Zapatista uprising, the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas was guided by a doctrine of liberation theology and supported organizing efforts in the indigenous villages of Chiapas. The Catholic Church’s moral weight enabled it to play a key role in upholding women’s rights and creating new opportunities for women’s participation. At the same time, women have had to fight for recognition within these institutions. External actors and influences were important, but the actions of the women themselves were just as critical, perhaps even more so. Finally, the EZLN has demonstrated an ability to evolve over time, strengthening women’s leadership in the movement, acknowledging machismo within its own ranks, and developing a more complex analysis of gender-based violence and discrimination.

There is still much work to do before reaching full equality and liberation for women. It is difficult to appreciate the enormity of the changes that have already occurred, however, without understanding the starting point. Before the Zapatista uprising, women in the indigenous communities of Chiapas described having limited control over their own lives and many of the decisions that impacted them. They were often married against their will. With little access to birth control, it was common for women to have a dozen children or more. Domestic violence was generally considered normal and acceptable behavior, and a woman could not leave the house without her husband’s permission. There was also a strict and gendered division between public and private spaces. Women’s confinement to the private sphere translated into very limited participation in public life. It was rare for women to attend public meetings or community assemblies. During the years I lived in Chiapas, I heard certain phrases over and over from women in Zapatista communities: “Siempre nos decían que las mujeres no tenemos derechos” (They always told us that women don’t have rights); “No nos tomaban en cuenta” (They didn’t take us into consideration); and “Antes las mujeres no participaban” (Before, women did not participate).

Zapatista women make a clear distinction between women’s lives “before” and women’s lives now. Older women tell younger women their stories because they have experienced many of these transformations themselves. Younger women repeat the stories their mothers and grandmothers have told them to ensure that this past is not forgotten, and to serve as an ongoing reminder of how much has already been won. Here are a few of these elders’ stories.

Amina, a Tzeltal elder from the Garrucha region, grew up on a finca called Las Delicias—one of the large landholdings that exemplified the historic inequality in Chiapas. At the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering in 2007, she stood up slowly, took the microphone, and spoke clearly and deliberately to the thousands of non-Zapatista women who listened attentively to her story. Amina explained that she did not know exactly how old she was, but her back was stooped with age and years of hard work. After introducing herself, Amina apologized for not speaking much Spanish, but went on to describe the living conditions on the fincas with great eloquence. Although she was talking about events that had taken place many years ago, her voice shook with rage and sadness as she spoke.

The patrón [landowner] sent us to work and he didn’t care if we died from working. My parents worked very hard, but it was always for the patrón. We didn’t have anything to eat because all our parents’ work was for the patrón. The only thing we had to eat was ground-up chili mixed with corn and water. Sometimes we ate banana roots, or we mixed green bananas in with the corn for the tortillas so it would go further. We often went hungry because we worked very hard, but all the work we did was for the patrón.4

The Spanish word patrón means boss or landowner. But, because of the extraordinary relationship between the owners of these large plantations and the indigenous peasants who worked for them, the patrón was much more than this—he exerted absolute control over many aspects ofthe peasants’ lives. The history of deep inequities in Chiapas, illustrated by Amina’s life story, began with the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century. The Spanish colonial elite sought to control land and indigenous labor in the Americas, and created multiple systems of labor exploitation to do so. The system of encomienda, established at the beginning of Spanish colonial rule, gave the conquistadors control over indigenous people, who were often treated like slaves and subject to harsh punishment and abuse. Encomienda was effectively abolished by the early seventeenth century and gave way to other, slightly less brutal systems of labor exploitation. By the end ofthe seventeenth century, the patrimonial hacienda system (or finca system as it is better known in Chiapas) had emerged, which trapped indigenous laborers through debt peonage, often from generation to generation. Fincas were extensive and largely self-sufficient estates. Peasant laborers who lived on the fincas were typically given small plots of poor-quality land with which to support themselves, but had to work for the landowner from sunup to sundown. Amina continued:

Our parents never had any land to work. Only on the moun-tainside—that’s where they would give us a little bit of land. “Go work in the hills. Go plant your corn up there.” But the corn didn’t grow. When the corn was starting to sprout, the badgers would come—the badgers and the tepezcuintles [large rodents]. So when my father went to the cornfield, there wasn’t any corn growing, because the wild animals had come and eaten the corn, knocked it over. But there was plenty of corn for the patrón, because his fields were in the valley. He knew there were animals in the hills that eat the corn, but they would send our parents up into the hills to work. That’s why we were so poor when we lived on Las Delicias.

In the colonial period, the largest fincas were owned by religious orders. During La Reforma, a period of modernizing liberal reforms in the mid-nineteenth century, much of the land owned by religious orders in Chiapas passed into the hands of a small group of families. This group, which would maintain a tight grip on wealth and power for the next century and a half, became known as la familia chiapaneca (the Chiapanecan family). Seeking to curtail the power of the clergy, La Reforma mandated the sale of church lands but also most communal lands held by indigenous towns and villages. The result was the enrichment of large landholders and worsened conditions for impoverished, landless peasants.

The modernization of Chiapas’s economy and successive land distribution programs meant that most of the true fincas had been dismantled or whittled down in size by the 1970s. Although the remaining fincas were shadows of their former selves by the 1994 Zapatista uprising, memories of life on the fincas were formative for many indigenous campesinos (peasants) who became Zapatistas, and exploitative finca-like conditions persisted on properties held by the same landowners. Many indigenous peasants like Amina, who now make up the Zapatista support base, lived and worked on fincas themselves, or remember the stories of misery and exploitation that their parents and grandparents told them.

“The men also had to carry heavy loads to the city,” Amina said. “They had to carry boxes on their backs because there were no horses and no roads. They carried boxes of eggs and boxes of chickens to Comitán because that’s where the patrón’s children lived.” Since there were no roads, the indigenous peasants often had to carry the landowner himself to and from the city as well. Murals in Zapatista territory that depict life on the fincas often include an image of the landowner and his wife sitting in an exquisite litter and being carried by several indigenous peasants.

During the women’s gathering in Morelia, Zapatista women described similar conditions in that region. They spoke of having to work on the fincas because they did not have their own land. “Even though we worked very hard, we were barely even paid,” they said. “That’s why we never had any money. Sometimes all they gave us were the leftovers from the day’s meals, or a little bit of salt.” When the women were sick or had some other emergency, they had to ask the patrón for help to buy medicine. “Then we would be in debt to the patrón. There would be more and more debt and we had to pay the debt little by little by working for him.”5 It was common for indigenous peasants to be perpetually indebted to their patrón.

Amina described the physical abuse that indigenous peasants were subjected to.

You did one thing wrong and you could get whipped. The whip was made of leather hide and was very tough. The punishments were so harsh you could pass out from the pain. They didn’t like you to speak back, and if you did, they would make you pay even worse. They tied our naked husbands to a tree; they beat them and left them there, tied up and naked, for one or two days. They made us sit on sharp stones until our knees bled. They did all these terrible things to us, and it was even worse when we were sick. They said we were just lazy and we were making up that we were sick, but it’s not true. We really were sick, but it was because of all the work they made us do. The patrón treated us like animals, worse than animals. Their animals, their dogs and chickens, their pigs, were all well fed, and where the animals lived was much better than where we lived.

We didn’t learn to read, no one from Las Delicias did. There were no teachers to teach us. So today, none of us who grew up there know how to read or write.

The men had to leave very early to work for the patrón; they started working at five or six. But the poor women, they weren’t free either. Some women had to grind salt for the patrón’s cattle. We had to grind big sacks of salt for the animals. Grinding salt with a rock is very hard work, and it had to be ground up very fine so his cattle could lick the salt. Other women had to make tortillas. We didn’t have a grinder to grind the corn; we ground pots and pots of corn by hand. The patrón wanted the women making tortillas to be there by six or seven in the morning. When he woke up he would go to the kitchen, and if there weren’t enough tortillas in the basket, the patrón would kick the basket. He would send the basket flying because it wasn’t full of tortillas. That’s what the women had to put up with.6

Indigenous women provided the domestic labor on the fincas. Zapatista women from the Morelia region explained that women worked for the owners of the plantations “like servants, like peons.”7 They cooked for the patrón, preparing pozol (a drink made of corn dough mixed with water), tortillas, and tostadas. They fed and cared for the landowner’s animals, washed his clothes, cared for his children, and cleaned his house. “When we finished our work, we would eat a little,” said the women from Morelia, “if there were leftovers from the landowner’s table. But they didn’t let us eat in the house. We had to go out where the animals slept to eat.” In addition to working for the landowner or his wife, indigenous women were responsible for their own families. “At six or seven at night, the woman would go back home and do all her own work,” they added. “Grind the corn, make tortillas, wash the clothes, and clean the house.” And yet women often did “men’s work” as well. During the coffee harvest, for example, women joined the men in the fields. If the family had a small plot of land, women often tended that land by themselves while the men were laboring for the landowner. Amina continued:

The women made tortillas for the men working in the fields, who were planting coffee and planting sugarcane to make panela [a solid block of unrefined cane sugar] for the patrón.

But we didn’t have any sugar for ourselves. The panela belonged to the patrón. My father couldn’t plant his own sugarcane because he was working for the patrón. The children would bring the tortillas to the men making the panela, but they couldn’t even let the children taste the foam. They had to be careful because of the patrón. They couldn’t touch anything, not even a small piece of sugarcane.8

The patrón and his family lived in the casa grande (ranch house) with opulent and spacious living quarters. The indigenous peasants, on the other hand, typically lived in small huts with mud walls, thatched roofs made of cane leaves, dirt floors, and no running water.

It was not uncommon for women to face sexual assault at the hands of the landowners.

The women would go to the casa grande to make tortillas for the patrón. But the patrón didn’t want the older women to work in his kitchen. He didn’t want them there because they always carried their babies with them. He wanted the young women to work for him. But the patrón is bad, he’s very bad. The young women said he wanted to rape them. They told their mothers and fathers they didn’t want to go back to work in his kitchen. They didn’t want to make torti-llas for the patrón. Why? Because they saw that the patrón is bad. So the mothers went to work instead. But he didn’t let the mothers work. He wanted the young women. One day the patrón ordered all the fathers to go get their daughters. So he could rape them! The old men who didn’t obey, he hanged them from a tree. That’s what those patrones were like. The one who hanged the fathers, that was Don Enrique Castellanos. [Don is an honorific in Spanish, placed before a person’s first name and used as a sign of respect.]

The widespread rape of indigenous women by colonial landowners was one source for the emergence of mestizo people of mixed Spanish and indigenous heritage, who make up the majority of the Mexican population today. “Sometimes the young man had to ask the patrón for a young woman’s hand [in marriage] instead of asking her father,” said the women from Morelia. “The patrón might keep the girl as his lover for a year before he handed her over to the young man. Then the women would have the patrón’s children.”9 On the large plantations of Chiapas, these practices had persisted for several centuries. Amina explained:

There was another finca called Porvenir. [The landowner] Don Javier Albores, he also had children with his servants. The fathers couldn’t say anything because they had already seen that if they didn’t hand over their daughters, they would be hanged. They couldn’t do anything, but they knew the young women were being raped. All the young women! Not just one or two, it was all the young women. The women he had already raped, they could walk by the patrón. It didn’t matter if he saw them because he didn’t care about them anymore. That’s why Don Javier Albores had so many children on his finca.

That was what life was like when we lived on the fincas. It was all large coffee plantations and sugarcane plantations, all owned by the patrones. They had us under complete control. We had to work all the time and we had to do whatever they told us to do. What one patrón did, the rest of them did as well. El Rosario, Las Delicias, Porvenir, those were the fincas I saw with my own eyes, and all those landowners were the same.10

When the Zapatistas took over vast tracts of land throughout eastern Chiapas, including Las Delicias, the finca where Amina grew up, they were reclaiming land that indigenous peasants had been working for generations and that had historically belonged to their ancestors. “In 1994 it was all over, thank God,” said Amina. “If it hadn’t been for that, we would all be slaves, like before, like our mothers and fathers were. That’s what we’re fighting for—so we can be free.”

Not all Zapatistas lived on fincas. Many of them lived—and continue to live—on ejidos or rancherías. The rural poverty of landless peasants helped fuel the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and the Mexican Constitution of 1917 promised to restore the ejido system, a precolonial structure of communal landholdings. The ejido system was an important component of land reform, but was not implemented in most of Mexico until Lázaro Cárdenas became president in 1934. During the Cárdenas administration, the government redistributed thousands of hectares of land in Chiapas. Thousands more would be redistributed in the decades that followed. The ejido system thus became the foundation on which peasants throughout Mexico were able to secure permanent title to their lands and to fight for further redistribution. Until the Mexican Constitution was amended in 1992, ejidal lands could not be divided or sold. Although many ejidos are made up of poor-quality land and their residents continued to confront difficult living conditions, by establishing independence from the fincas, these communities were able to develop a higher level of social cohesion. For example, Morelia and La Garrucha, two of the five villages that now serve as municipal centers of Zapatista territory, were formed as ejidos in 1945 and 1954, respectively.

Rancherías, on the other hand, are small villages where peasants managed to establish their own land, but were not as successful in truly escaping the fincas. Fearing land reform during and after the Cárdenas era, Finqueros (owners of the fincas) often gave some of their poorest-quality land to the indigenous laborers, hoping to ward off more drastic land distribution. Even though they now had title to their own land, the peasants who lived on the rancherías were usually forced by economic necessity to sell their labor to the finqueros for a pittance.

Victoria, who grew up on a ranchería, is now a well-known Zapatista comandanta. She asked me to use a different name for her and not to disclose any of her personal details. She also told me that rather than focusing on her more conspicuous role as a public figure, she wanted to convey the impact that illness, disease, and the lack of adequate health care had on her and her family, and how this motivated her to become involved with the Zapatista movement. She decided to write her story down herself rather than be interviewed. She handed me several sheets of notebook paper, her story handwritten in carefully printed letters: “My parents always suffered from sickness and from hunger because they didn’t have enough money or good land to work on. My father would go out and look for work on the coffee plantations to earn a little money and buy corn to feed us, because we were thirteen children. Three of my brothers and sisters died from curable diseases because we couldn’t get them to a doctor, so only ten ofus survived.”

When Victoria was a child, it was tragically common for poor children to die from curable diseases in rural Chiapas. In 1994, infant mortality in Chiapas was twice as high as in other parts of Mexico: 54.7 per thousand in Chiapas compared to 22.4 per thousand in Mexico City and the northern states.11 Rural indigenous villages faced appalling health conditions and extremely limited access to health care. There were no doctors or clinics in the communities and hospitals were inaccessible and unwelcoming to indigenous people. Many indigenous villages are far from the nearest city and at that time there were few roads. As a Zapatista health promoter explained, patients had to be carried, sometimes for several hours, on a stretcher fashioned from branches or a hammock made from rope. It was not surprising, she said, that they often did not make it to the hospital.12 For Victoria’s family, and many others, living in poverty was inextricably linked to ongoing problems with sickness and disease.

When I was a child, we didn’t have any beans to eat. We just ate tortillas with salt. We didn’t have good clothes to protect us from the cold, much less shoes. I was often sick, but even though I told my mother that my head hurt, she couldn’t give me anything because she didn’t have money to buy medicine. My father drank and my mother would scold him. Later on my father stopped drinking.

When I was thirteen years old I left school and started working in the fields. I would go with my father and my older brothers to work in the cornfields, to plant and clear weeds. My father didn’t have enough money to buy clothes for me, so I looked for work in the fields of the kaxlanes [nonindigenous people] to make a little money and buy my own clothes and shoes.

In 1990, I was invited to a workshop about health. I decided to attend this workshop because of the problems I had seen in my own family. There was never enough money to buy medicine and we didn’t know about medicinal plants. I looked for work to pay my bus fare to get there. My father also supported me with a little bit of money when he could so I could keep taking the course. I received midwifery workshops from the same doctor. Later on I began to assist births and continue to help women.

In 1991, the same man who invited me to the health workshop told me about an organization that fights against injustice and asked me what I thought. He told me to think about whether I wanted to join this organization. Since I was a little girl, I have seen people in my family get sick because they don’t have enough to eat and then they don’t have any medicine. When I was a child, I saw my younger sister die in my mother’s arms while she cried for her baby daughter. All the suffering I had seen made me very angry, because so many poor people die, but people who have money don’t die from curable diseases. So I decided to join the struggle. I felt like I didn’t have any other choice because we will only be able to put an end to this injustice by being organized and united.

I started going to the organization’s meetings. Whenever there was going to be a meeting in another village, this compañero would let me know. I would sell one of my chickens or I would look for work to pay for my bus fare. Sometimes the other compañeros gave me money but not always, because there weren’t very many of us. There were only five compañeros in our village and since there were two of us traveling to the meeting, there wasn’t enough to pay for us both. I always went to the meetings and I was very excited because I learned so much about our organization and they explained all about the political situation. When we arrived back at our village, the compañeros and compañeras would get together and we would share all the information from the meeting, including the tasks and the agreements, and we would explain that women should fight to defend their rights.

Some of the men didn’t understand why women needed to participate in the meetings. They said it was enough for the men to come to the meetings and that they could go home and explain the information to the women because they lived together. I told the men that the women should come to the meetings too because their participation was very important and that in other regions women were participating too.

This compañero supported me because it was hard for me at first. He always told me to share the information that we had brought back with us from the meeting. Sometimes I forgot something because I was so nervous, and I still thought that men knew better than me, and then he would fill in what I had left out. The men didn’t like it and said he should be the one to give the talk because when I spoke, it was a waste of time. But the compañero didn’t pay attention to them and he kept telling me to speak first.

When my father was alive, he didn’t say anything about me going to the meetings, because he agreed with the organization. He liked that I was part of it and he gave me permission to have meetings at our house. When the war started in 1994, I went off to fight together with the other milicianos and milicianas [members of the Zapatista militia]. My father was very concerned about what was going to happen, whether we were going to return or not. When we retreated from the municipal capital, all the milicianos from my area went back to my house. My mother prepared breakfast for the milicianos and she fed us all.

That same year, in September, my father got sick. He was very ill and we took him to see the doctor in San Cristóbal. The doctor wanted to keep him in the hospital for three days but they were going to charge 1,000 pesos per day, and the doctor said there was no guarantee that he would get better. My father heard that and said he didn’t want to stay because we didn’t have the money, so we went back home with a little bit ofmedi-cine. He couldn’t hold on and he died on December 6, 1994.

Abuse from the landowners and extreme poverty were not all that women had to endure. María, a Zapatista woman who lives in the autonomous municipality Miguel Hidalgo, illustrates the ways in which many women also suffered at the hands of their own fathers and husbands. María was thirty-six during the Zapatista uprising in 1994—already married with several children—so she is old enough to have witnessed the span of change between generations ofwomen in her family. Shortly after the uprising, she was chosen as a local representative and then a women’s coordinator for her entire region. I went to María’s village to interview her and we walked to the nearby river to talk. María sat down on a rock near the water. She smoothed her hands over her faded nagua—the long, dark-blue wraparound skirt traditionally worn by Tzeltal women—and straightened her white blouse embroidered with flowers. She gazed at the women washing clothes and the children splashing in the water as she began to tell me her story.

My father treated my mother very badly. He drank and hit my mother. He would throw her out and I would be left alone with my sisters and brothers crying. She would be out of the house all night; she went to sleep at my grandmother’s. That happened many times. Ever since I was little I saw how my mother suffered. My grandmother tried to talk to my father but he didn’t want to listen because he had the vice of drinking too much.

I wanted to go to school, but my father wouldn’t let me. He didn’t send me to school because I was a girl. He said there was no reason for me to study because men have more rights. My mother didn’t want me to go either. They only wanted me to be in the kitchen and tending to the sheep. My parents valued the boys more; that’s just how it was back then. They cared more, they paid more attention to boys than girls.13

During a collective interview in the autonomous municipality Olga Isabel, a Tzeltal region in northern Chiapas, Zapatista women also described how their own families and communities often treated women unequally. When a child was born, they explained, the parents were pleased if it was a boy. If all his children were girls, a man might leave his family and look for another wife. Boys and girls were treated differently as soon as they were born. “Girls were scorned,” they said. “The father sees that it’s a girl, and if she’s sick, he’s not concerned. The mother loved them all the same, so she wanted to give them the same amount of food. But since it was the man who was supporting them, the boys got more food to eat.”14

María began working at a young age, which was normal for girls at that time. “I was ten years old when my mother taught me how to make tortillas,” she said, “because she was busy taking care of my younger siblings. My mother had sixteen children and I’m the oldest. That’s why I had to be in the kitchen helping my mother. When I was twelve I started doing harder work, carrying water, carrying firewood.”15 The gendered division of labor in the indigenous communities of Chiapas meant that women were responsible for the domestic work, while men worked in the fields. “Women’s work,” however, was not necessarily less physically demanding than “men’s work,” and often included carrying young children the entire time. And, where a man’s workday ended when he was done in the fields, women worked from early in the morning until late at night and had little time to rest. The Zapatista women from Olga Isabel described getting up at three in the morning to start working in the kitchen. Sometimes they helped the men in the fields and then returned home in the afternoon to grind corn and wash clothes, sometimes not resting until ten or eleven o’clock at night. Children’s experiences mirrored those of their parents. Boys accompanied their fathers to work in the fields and then had time to play, whereas girls were expected to help their mothers from a young age. María continued:

My father also said I had to help my mother because she was sick so often. We didn’t know anything about hospitals back then and we never had any medicine. My mother was always sick because she had so many children. She had fevers, headaches, her whole body would hurt. My younger siblings were often sick too; they would have a cough and a fever. Back then, they had a custom of listening to your pulse when you were sick. They would take your hand, listen to your pulse, and then give you advice. When my grandmother listened to their pulse she said it was my father’s fault because he hit my mother so much. He hit me too, when I tried to help my mother, when I tried to defend her because I didn’t want him to hit her. My mother would be bathed in blood. Her family got angry and complained, but back then there were no authorities to resolve those kinds of problems. Back then, when young couples got married, the elders would say, “When your husband hits you, don’t tell your mother and father, keep it a secret. If you are bleeding, you should hide the blood. If you cry, you should hide that you’ve been crying so no one knows your husband is beating you.” That was the advice our own elders gave us.

I was seventeen when I got married. My father-in-law came to speak to my father. I had never met my husband and I didn’t want to get married. My mother and father, they forced me, they sent me away. It’s one of the bad customs we used to have. They would say you’ll get sick if you don’t agree to get married.16

This situation was the norm throughout rural Chiapas. During a regional women’s gathering in Morelia, a group of Zapatista women explained that, in the past, it was the father who decided on a husband for his daughter and nobody asked the young woman. If the father accepted the alcohol offered to him by the young man, the woman had to go with him even if she did not want to. The custom was that the young man worked in his father-in-law’s house for a year to pay for the girl. Sometimes women were married as young as twelve or thirteen years old.

María was one of sixteen brothers and sisters, and she has twelve children of her own, which is not unusual for women of her generation. According to the women from Morelia, “Women had a lot of children back then. It was common for a woman to have thirteen, fourteen, fifteen children, sometimes even sixteen children, and the mother was left very weak.”17 Women had little or no access to birth control, and were expected to bear however many children “God sent them.”

The women from Morelia also explained that indigenous men internalized the patrón’s mentality, which influenced how they treated women in their own communities. “For women it was like having two bosses telling us what to do,” they said, “because, at home, men treated women the same way the landowner did. Men didn’t treat women with respect. They forced women to work because they were copying the patrón.”18 María continued:

My husband used to get drunk a lot. He didn’t hit me but he spent all our money. He would go find work but then he came back without any money. I had to work, raising chickens, sheep, and pigs, because I needed money to take care of my family.

We joined the struggle before 1994. The first authorities in the organization counseled us, talked to us about this path Men and women insurgents came to speak to us as well. When we first joined the organization we had meetings, but always at night. We couldn’t have meetings during the day.

Women have the right to participate now and we are not as timid. Before, we felt too much shame to speak up. When I began participating with the word of God and the catechist asked us questions, I would cover my face with my shawl. I couldn’t speak. I felt very afraid. In the EZLN, I began as a local representative. I understood a little bit, not everything, because I don’t know how to read and write. You get past the fear little by little. But women have the right to participate now; it’s not only men who can participate. Women also have the right to go out and see new places. When we’re in our village all the time, we never learn anything new and nothing changes.

Before, my husband didn’t give me permission to leave the house. If there was a meeting, only the men went. He would say, “How are your children going to eat? Who’s going to take care ofthe house? Who’s going to cook?” In 1994, he began to change and he has changed little by little. Now the men also stay at home and take care of the children when the women have somewhere to go. Things have changed a lot. Other women who are not in the organization, they haven’t experienced these changes. They are still suffering and nothing has changed for them. That makes us very sad.19

The EZLN was born out of the conditions ofinequality and marginalization described by Amina, Victoria, and María. The injustices that the rural communities of Chiapas faced were the roots of a revolutionary movement. These three individuals and many others went on to make history and to change their own destinies, as Zapatistas and as women.

Indigenous elders during a religious ceremony in the village of Diez de Abril. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Subcomandante Marcos and a young insurgent woman. (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)