As soon as Zapatista soldiers stormed San Cristóbal de las Casas, it was clear that the EZLN was more than an insurgent army. The government quickly realized that much ofthe movement’s real power lay in the strength and cohesion of the Zapatista support base—the civilian communities that belong to the EZLN, and that broad sympa-thy for the Zapatistas throughout Mexico also represented a serious threat to the political status quo. Beginning in 1994, the Mexican government responded with violence directed primarily at Zapatista civilians. Some of these military incursions were attempts to displace Zapatistas from the land they had occupied, but most of them were not. The motivation for the violence was to undermine the EZLN. In many cases, the Mexican armed forces attacked Zapatista villages that were not on reclaimed land, but where it was known that the movement was particularly strong.

Morelia was one such stronghold. At a regional women’s gathering in Morelia in 2001, Zapatista women recounted different instances of military aggression against their villages. “In January 1994, they began publicizing that everyone in Morelia were Zapatistas,” the women recalled. “The soldiers said clearly that they wanted to do away with us all, that they were going to turn us all into dust.”1 On the morning of January 7, 1994, hundreds of Mexican soldiers swarmed into the town ofMorelia, going from house to house and forcing all the men onto the basketball court in the center of town. “They wouldn’t let us go down where they were torturing the men,” said the women. “We wanted to bring them food but they wouldn’t let us. They kept us locked in our houses and threatened us with their guns. They kept watch on every corner.” The soldiers detained thirty-five men and took them to the Cerro Hueco jail, and disappeared three ofthe town’s elders.

One of the three elders was Comandanta Micaela’s father-in-law. “He was an old man who worked in the cooperative store,” remembered Micaela, one of the regional coordinators from Morelia who shaped my project in Chiapas. There was calm anger in her voice as she told me the story. “They took a seventy-two-year-old man away and assassinated him. I was with him when they came into my house and took him away. My children were there too. He said he wanted to protect his grandchildren, and he never thought the soldiers would come into his home. The soldiers broke down all the doors looking for my father-in-law. They took him away and we never saw him again.”2

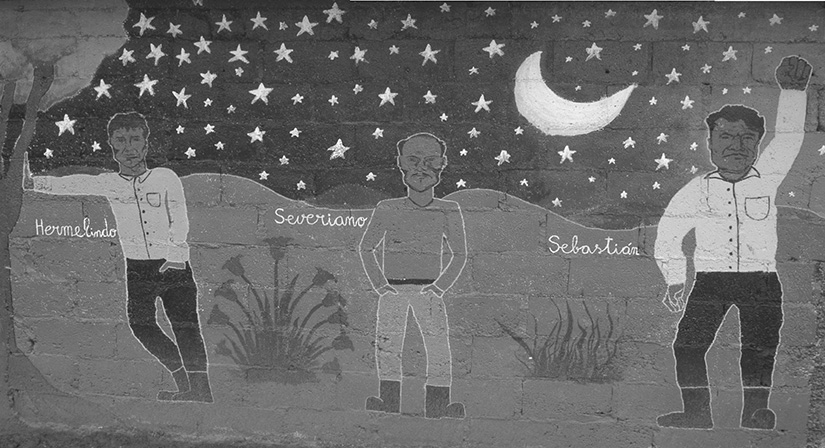

The faces of the three elders, now known as the “Martyrs of Morelia,” are depicted in a mural. “All we found later were their bones,” said the women from Morelia. “We don’t know what ate their bodies, whether it was vultures or dogs.”3 This type of repression would come to characterize the conflict in Chiapas.

After the uprising in 1994, while the EZLN consolidated its base and continued to recruit new people, it also engaged in peace talks with the Mexican government. These negotiations would last for two years and culminate in the signing of the San Andrés Peace Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture, signed in 1996 but never implemented by the government. Women participated side by side with men in this dialogue and brought gender-specific demands to the table. The entire time the Mexican government was negotiating with the EZLN, however, it was also waging low-intensity warfare against the Zapatistas. Low-intensity conflict—the term often used to describe the situation in Chiapas—refers to a counterinsurgency doctrine promoted by the United States for use against popular movements. It includes the calculated combination of military and paramilitary violence, a constant military presence, ongoing harassment and intimidation ofthe civilian population, and other psychological tactics intended to undermine popular support for the Zapatistas.

In December 1994, the EZLN declared the existence of more than thirty autonomous municipalities. Up until then, the conflict zone was considered to include the official municipalities of Altamirano, Ocosingo, and Las Margaritas, which correspond to the Zapatista regions of Morelia, La Garrucha, and La Realidad, respectively, and the government had established a network of military bases and checkpoints surrounding that area. By announcing its autonomous municipalities in the highlands and the northern zone, the EZLN dramatically expanded the definition of Zapatista territory and effectively broke out of the military encirclement.

In February 1995, in the context of ongoing peace negotiations and in spite of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s promise that the army would only fight if first attacked, the Mexican military launched an offensive against the Zapatista communities. Instead of returning fire, the Zapatista insurgents, political leaders, and tens of thousands of Zapatista civilians fled to the mountains. The soldiers ransacked the abandoned villages, leaving destruction in their wake as they advanced through Zapatista territory. At the time, Subcomandante Marcos was in Prado, a village in the Garrucha canyon, and that region bore the brunt of the offensive.

A mural depicts the three martyrs of Morelia, who were disappeared by the Mexican army in 1994. (Photograh by Francesc Parés.)

Doña Manuela is a Tzeltal elder from the village of La Garrucha. Her stooped shoulders and wrinkled face testify to her years on this earth, but her easy chuckle gives away her youthful spirit. As a midwife, she has helped ease so many new lives into this world that she is known as the godmother of the entire canyon. Several years after the military offensive, Doña Manuela shared her memories of February 9, 1995.

I remember that I had just finished baking bread when we got the news from compañeros from other villages: “The soldiers are coming!” They had already fled from their homes. We left quickly for the mountains. The airplanes were flying overhead by then. They were flying so low! I don’t know exactly when the soldiers actually entered the village because I had already left with the children and the other elders. We hid up there [gestures toward the hills] where it’s full of those animals that hang from the trees and cry a lot. And the trees, my goodness, what enormous trees! We slept below those trees and it was the trees that protected us.

A few days later, the compañeros arrived and they were frightened, really frightened. They had stayed in the village until they knew we were safe. They hid in my son’s house. And right above them, the helicopters were circling around and around. Those poor compas were hiding in that house, with their shotguns pointed in the air. They could have fired. They could have brought down those helicopters. But if they had fired, we are the ones who would have suffered. The soldiers would have come after us.

So much suffering, my goodness! I spent a month up there in the hills, with the trees and the little animals that cry and cry. Some young women were pregnant and gave birth up there in the hills. Now they’re back in their villages and the babies that were born up there, beneath those big trees, they’re little children now.4

The Mexican army did not succeed in detaining the Zapatista leadership, and the offensive only served to fan the flames of public support for the Zapatistas. The government eventually called off the attack and peace talks were renewed, but the Mexican army did not retreat from the jungle. It established formidable army bases in Guadalupe Tepeyac and San Quintin, in the heart of Zapatista territory. The strained relationship between dialogue and violence would continue to mark this stage of the Zapatista movement, and women would end up on the front lines in defending their communities from military attack.

Major Ana María, who led the EZLN’s takeover of San Cristóbal, and Comandanta Ramona, a civilian political leader from the highlands of Chiapas, both participated in the initial peace talks between the EZLN and the Mexican government. They soon became two of the most well-known Zapatista women. The visible role of Zapatista women in the peace process helped shape the public image of the EZLN as having significant participation from women, although the fact that only two of the nineteen delegates were female also highlights the limited number of women in leadership at that time.

Within the first few days of January 1994, while there was still active combat in Ocosingo and the Mexican military was bombing the hills around San Cristóbal and the jungles of Chiapas, solidarity with the indigenous uprising began to build. Samuel Ruiz, the bishop of the Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas and an advocate for the poor, asked for a truce and a suspension of hostilities. He would later be called upon to mediate negotiations between the EZLN and the Mexican government. While people who mobilized in Mexico and around the world were overwhelmingly sympathetic toward the root causes of the Zapatista uprising, there was also a push from civil society for both sides to put down their weapons and negotiate a peaceful solution. On January 12, over one hundred thousand people flooded the zócalo—the enormous plaza in the center of Mexico City—to demand an end to the fighting. That same day, President Salinas accepted the EZLN’s call for a cease-fire.

It was clear by then that the EZLN stood little chance of beating the Mexican army militarily, and the Zapatistas accepted civil society’s call for dialogue and agreed to negotiate with the government. “We do what the people ask,” said Major Ana María. “The people have asked that we try this way. We are going to try it, because we don’t like to kill and we don’t like to make war. That is why we decided to sit down and negotiate, to see what we can get out of it. But if things are not resolved this way, we will have to continue.”5

One event that helped clear the way for peace talks was the freeing of General Absalón Castellanos Domínguez, whom the Zapatista troops had captured on January 3. As governor of Chiapas from 1982 until 1988, he was infamous for the violent repression of campesino movements. On February 16, five armed Zapatistas—three men and two women—handed Castellanos Domínguez over to the government’s representatives. Captain Maribel, one of the two Zapatista women, had been assigned to guard the general. In a 1996 commu-niqué, Subcomandante Marcos wrote, “When General Castellanos Domínguez is returned to the government, Captain Maribel is the first woman rebel to have contact with the government. Commissioner Manuel Camacho Solis extends his hand to her and asks her age. ‘Five hundred and two,’ says Maribel, who counts all the years since the rebellion began.”6

The EZLN’s initial set of thirty-four demands presented for negotiations revolved around the transition to democracy in Mexico, land reform, adequate health care, educational opportunity, and indigenous autonomy. It also included a set of proposals from women, developed through a process of consultation led by Comandanta Ramona. “In our communities, girls suffer from malnutrition and, before they’re even done growing, they’re already mothers,” she said during a session of the peace talks. “Many women die in childbirth. When an indigenous woman is thirty or forty years old, her body already seems old and is full of illness.”7 The list of women’s demands included twelve points, the first of which was “birth clinics with gynecologists so that campesina women can receive necessary medical attention.”8 Several demands had to do with alleviating women’s oppressive load of domestic work: building child care centers in the indigenous communities, as well as corn mills (to grind corn for making tortillas) and tortillerías (stores that make and sell tortillas). Several other demands had to do with local economic development: technical assistance, materials, and funding to start small businesses including bakeries, raising farm animals, and producing artisan crafts. Finally, the women’s demands sought to address the impact of poverty and marginalization on children by asking the government to build rural preschools and to send enough basic food goods so that children in rural villages would not go hungry.

The peace process was also an opportunity for the EZLN to begin its dialogue with national and international civil society. International Women’s Day—March 8, 1994—came as the first round of negotiations concluded, barely two months after the Zapatista uprising. The world was just getting to know the Zapatista movement, and many of the EZLN’s supporters were particularly touched by the Zapatista women. The EZLN had dubbed itself “the voice of the voiceless,” and the indigenous women of Chiapas were the most subjugated, the most forgotten of an already marginalized people, breaking this history of silence, rising up to take on their government, and inspiring movements all over the world to challenge global capitalism. Captain Irma made a speech during the International Women’s Day celebration. What has since become a familiar discourse to Zapatista supporters was, in the first few months of 1994, new and thrilling to solidarity activists.

I would like to invite all our compañeros, from the cities and from the countryside, to join in our struggle and our demands. Women continue to be the most exploited. . . . In order for this no longer to be the case, we need to take up arms, together with our compañeros, so they will understand that women can fight too, with a weapon in our hands. . . . Our struggle is a necessary struggle, so that our communities and our country can be free, not only for women but for all our people, who have been degraded for so long. We will continue onward with our struggle until we achieve our demands: bread, democracy, peace, independence, freedom, housing, and justice, because these things do not exist for us, the poor We are tired. We don’t want to live like animals anymore, and we don’t want someone always telling us what to do or what not to do. Today, more than ever, we should struggle together so that one day we will be free. We will achieve this, sooner or later, but we will win.9

The government’s negotiating team largely responded to the EZLN’s demands with empty promises and the creation of commissions to discuss the points further. The first round of negotiations ended in June 1994 with the EZLN rejecting the government’s proposals. Additional talks would not occur until after the govern-ment’s offensive in February 1995. Peace talks resumed in April 1995 in San Andrés Larráinzar, in the highlands of Chiapas. Throughout the peace talks, the government made a deliberate effort to offer only local and regional solutions, in an effort to quell any national ramifications of the Zapatista uprising. From the list of agreed upon topics, the government insisted on beginning with “indigenous rights and culture” in an effort to contain the Zapatista movement to “only” indigenous issues. The EZLN had initially wanted to begin with “democracy and justice” because, in its view, structural solutions were necessary to address the root causes of the rebellion. But the Zapatistas used the peace talks to draw attention to the “indigenous question,” also one of national importance since Mexico has sixty-two officially recognized indigenous groups and an indigenous population of over ten million people, making up about 10 percent of the overall population.10

During the San Andrés peace talks, the Zapatista delegates were all civilian leaders of the EZLN, so neither Subcomandante Marcos nor Major Ana María were part of the delegation. Comandanta Ramona had stepped down because she was ill with cancer, and the government’s negotiators were all men as well. When Comandanta Trinidad, an elderly Tojolabal woman, joined the Zapatista delegation a few months later, she brought a woman’s voice back into the dialogue. Wearing a colorful dress and plastic sandals, Trini, as she was often called, arrived with the rest of the Zapatista delegates on Red Cross trucks. She was greeted by applause from the large crowds who had gathered around the site of the peace talks. Like Ramona, Comandanta Trinidad often highlighted women’s concerns. In an interview published in La Jornada, Trinidad denounced the government for not taking the women’s demands seriously. “We, the comandantes, think a work session on women is important,” she said, “but the government does not want to give it any attention.”11

During one negotiating session, Comandanta Trinidad addressed the government representatives in Tojolabal and then asked them in Spanish if they had understood what she had said.12 The fact that the negotiations took place in Spanish exemplified the government’s expectation that it would set the terms of debate as well as its lack of commitment to truly understanding the conditions of misery and exploitation in the indigenous communities of Chiapas. The Zapatista delegation, which represented three Mayan-language groups, consistently objected to the government negotiators using overly technical or legalistic language, as well as their condescending tone and racist attitudes.

The San Andrés Peace Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture were signed after almost another year of talks. They state that the Mexican Constitution should be changed to recognize indigenous rights, and establish indigenous peoples’ right to choose their own authorities; to decide their internal forms of social, economic, political, and cultural organization; and to control the natural resources in their own territory. While this accomplishment was celebrated at the time, the San Andrés Accords were never implemented.

The topic of indigenous rights and culture was intended to be only the first of six in the peace talks. In September 1996, however, the EZLN suspended the negotiations. In addition to the San Andrés Accords not being implemented, the EZLN halted the dialogue because of continued militarization, repression, and persecution in Chiapas; Zapatista political prisoners; and the government’s lack of willingness to consider fundamental political reform. Silvia, a Zapatista woman from Morelia, did not attempt to hide her frustration when she described how the peace talks came to an end. “We’re demanding that the government withdraw the army from our communities so we can move forward with the dialogue,” she said, “because if our villages and communities are full of soldiers, how are we supposed to believe in the peace negotiations? As long as the government doesn’t keep its word about the agreements it already signed, there can’t be any more dialogue. It just doesn’t make sense.”13

The EZLN set forth five minimal conditions to return to the negotiating table, none of which have been met.14 For years, implementation of the San Andrés Accords was the EZLN’s principal political demand. Banners and chants at every Zapatista march carried this message. However, by the late 1990s, it was clear that the government had no intention of complying with the agreement it had signed and had little interest in continuing its dialogue with the EZLN. The other topics to be discussed with the government, including women’s rights in Chiapas, were therefore never addressed.

As the government’s position became increasingly apparent, the Zapatistas adjusted accordingly. Not only did the EZLN stop asking for support from the state, it developed an analysis ofhow social welfare programs and other types of assistance were often used to co-opt social movements, and stopped accepting any kind of government aid. The EZLN began defining its support base as “communities in resistance.” Paula, the young woman who left Mexico City to return home and join the EZLN the year before the uprising, explained, “Resistance means that we don’t need the government’s crumbs. They just give us their leftover scraps. But it’s not out of generosity, it’s because they don’t want us to organize. Poor people start fight-ing among themselves over the money. The government knows that and that’s what they want, for us to be divided. We don’t want that anymore, and that’s why we’re in resistance.”15 “Resistance” would become the predecessor of the Zapatista project of indigenous autonomy.

With peace talks off the table, Zapatista women shifted their focus as well. During the peace process, women requested resources and support from the government while also wanting to see changes in their own villages. Zapatista women continue to hold the government (and the capitalist system) responsible for many of the injustices in their communities. Over time, however, women stopped waiting for changes to come from the state and, instead, have fought to exercise their rights within the Zapatista movement and to transform the relations of power in their own communities. They have taken it upon themselves to make changes in their own homes and families. And they have continued to dialogue with women from civil society around women’s rights and liberation.

We saw the soldiers approaching and that’s when the women started shouting, “We don’t want the army here!” We didn’t want the soldiers to go into our houses, to rape the women. All the women got together and we chased them out.

—MARGARITA, a Zapatista woman from Morelia16

In January 1998, Margarita was one of about sixty Zapatista women from Morelia who successfully drove out Mexican soldiers trying to enter their village. A Tzeltal mother of three small children, she was willing to go with the rest of the women from her village, armed only with sticks, and confront the Mexican army to protect her family and her community. Zapatista women stood up to the Mexican armed forces time and time again, and women like Margarita became the public face of the indigenous communities’ militant but unarmed resistance against the incursions of the Mexican armed forces. Zapatista communities emerged from this period with a tremendous sense of their own strength and dignity, sabotaging the Mexican government’s efforts to undermine the EZLN through low-intensity warfare.

While the Mexican army has been ubiquitous in Chiapas since 1994, the low-intensity conflict escalated over the next several years.

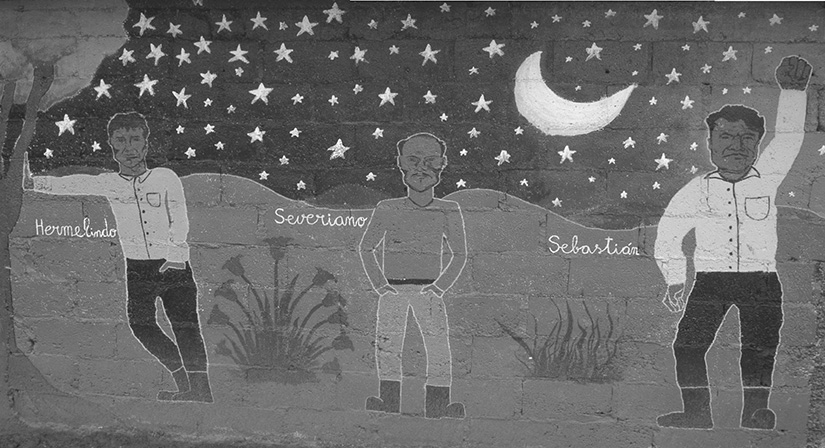

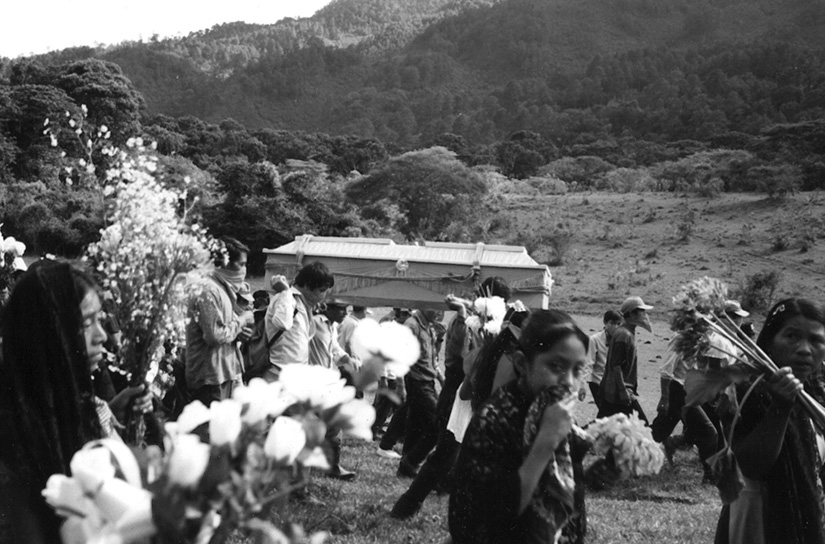

The coffin of a woman killed in the Acteal massacre in December 1997. (Photograph by Jutta MeierWiedenbach.)

The funeral of the victims of the Acteal massacre. (Photograph by Jutta MeierWiedenbach.)

A handmade cross to remember the women murdered in Acteal, placed outside the Cathedral during a march in San Cristóbal de las Casas to commemorate International Day for the Elimination ofViolence against Women, 25 November 2005. (Photograph by Francesc Parés.)

In 1998 it was estimated that a full third of the Mexican military— approximately seventy thousand soldiers—was stationed in Chiapas, and signs of military occupation were everywhere.17 The army had bases throughout the conflict zone, often right next to indigenous communities. Army trucks and Humvees rumbled down the dirt roads past Zapatista villages.18 Helicopters and airplanes swooped over the mountainous green jungle. The goal of low-intensity conflict is to destroy the EZLN without resorting to full-scale war, by tearing apart the social fabric and reducing external support. Where low-intensity conflict is succeeding, Bishop Ruiz once commented, it is “destroying the very souls of the communities.”19

After carrying out its military offensive in February 1995, the Mexican government faced increasing pressure not to use brute military force against civilian Zapatista communities. It also wanted to promote an international image of Mexico as a stable, democratic nation. On the other hand, the government still wanted to crush the Zapatista movement. So when it learned of the EZLN’s presence in the northern zone and the highlands of Chiapas, the Mexican government began to organize and finance paramilitary groups in those regions instead of relying solely on its own armed forces. The Mexican military already had a concentrated presence in the jungle and canyons—the Zapatista regions of Morelia, La Garrucha, and La Realidad. In general terms, the Mexican government continued employing military force in those regions, while paramilitary violence has been more prevalent in the northern zone and the high- lands—the Zapatista regions of Roberto Barrios and Oventic.

The Mexican government exploited divisions that already existed in the indigenous communities, sowed mistrust and fear, recruited villagers into paramilitary organizations, and then proceeded to arm, train, and finance them.20 In 1995 and 1996, paramilitary organizations sprang up first in the northern zone and terrorized Zapatistas and other community members opposed to the government—carrying out assassinations, kidnappings, and disappearances, as well as burning down schools, churches, and homes. Entire communities were displaced from their villages when they were forced to flee from the paramilitaries. Not only did these paramilitary groups act with impunity, they had direct support from local, state, and federal officials and often enjoyed protection from police and soldiers while carrying out violent actions.

In 1997, paramilitary violence spread to the highlands region, and culminated in the Acteal massacre. On December 22, 1997, members of a progovernment paramilitary organization in the highlands region opened fire on a church full of civilian refugees while they prayed for peace. The refugees were members of a religious organization called Las Abejas (the Bees) that sympathized with Zapatista demands but did not support armed struggle. Bullets splintered the thin wooden walls of the church and peppered the refugees as they fled into a ravine. Dozens of people were hacked to death by machetes. Members of the Seguridad Pública stood by on the highway about two hundred yards away as innocent civilians were massacred.

Of the forty-five people murdered, nineteen were women, eighteen were children, and eight were men. Four of the women were pregnant. There had been persistent rumors of the attack before it happened, so most of the men had left the refugee camp in Acteal to hide in the hills, mistakenly thinking that the paramilitaries would not openly attack women and children. Not only were the paramilitaries willing to murder innocent women and children, they brutalized the dead women’s bodies afterward. A survivor of the massacre testi-fied that one of the attackers shot a young woman to death “and after having killed her, lifted up her skirt and shoved a stick into her vagina.”21 Another survivor testified, “There was a pregnant woman from Quextic and once she was dead, he cut her belly open and killed the child that was inside the woman’s body.”22

On December 30, eight days later, I participated in a protest against the bloodshed and a mass held in Acteal to honor the victims. Each of the marchers was given a brick and instructed to carry it several kilometers down the winding highway between Polhó and Acteal. The red bricks were meant to represent the blood spilled, but they would be used to build something new to remember those who had been killed. Several days after the massacre, fresh dirt covered the graves of forty-five bodies and inside the dark shade of the church, the presence of death was still palpable. In the ravine behind the church, there was a path of vegetation that had been trampled flat by running feet and there were bullet holes in the trees. Women’s plastic sandals and children’s sneakers were strewn along the path. Dried blood was still visible inside one of the women’s sandals.

With the suspension of peace negotiations in September 1996, tension in Chiapas had mounted throughout 1997. With no dialogue underway, the Mexican government turned increasingly to direct force, and used the Acteal massacre as a pretext for a massive military buildup throughout Zapatista territory. The government claimed that it would act against paramilitary organizations, but not a single paramilitary group was disarmed or disbanded. Instead, the Mexican government geared up for a series of attacks on the Zapatista support-base communities. Dominga, a Zapatista woman from the community of La Garrucha, was thirty-two in 1998 when she described the low-intensity conflict in her region.

There are regular airplane and helicopter flights low over our community—extremely low. One helicopter flies by and takes pictures of us. We live with the fact that we are in danger every day. Every day the army trucks pass by here, sometimes stopping to take photos of us, and sometimes just to scare us, but they always pass by here. Soldiers regularly stop us to ask, “Where are you going?” and “What are you carrying?” They have even set up checkpoints on the highway to search community members who pass by. There hasn’t been any peace of mind here since 1995.23

Escalated militarization intentionally disrupted economic activity in the indigenous communities. “As women, we can’t work in peace in our houses or in our kitchens because we keep hearing the helicopters pass by,” said Margarita. “We can’t work in the collective vegetable garden or bakery either, because the helicopters keep coming, flying really low. That’s what the government wants—for us not to be able to work in our cooperatives, because we’re working for ourselves and the government wants to take away our ability to work and organize ourselves.”24 Whenever communities were in a state of alert, they could not plant or harvest crops. They had to stay close to home, or, in more extreme cases, take refuge in the mountains, hindering their ability to maintain even basic levels of subsistence.

At a protest following the Acteal massacre, marchers carried bricks to represent the red of blood spilled and the commitment to build something new in the wake of the violence. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Thousands of federal troops living side by side with indigenous communities had negative ramifications on community health, many of which had a particular impact on women, such as the dramatic increase in prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases. “The soldiers bring prostitutes to bathe in the river,” said Claudia, one of the women from Moisés Gandhi who defended her village from Mexican soldiers. “But it’s not their army barracks—it’s Zapatista territory.”25 While the Zapatistas’ public discourse often tends to be antagonistic toward prostitution, I also had a number of private conversations with Zapatista women who blame the Mexican army rather than the prostitutes themselves, and who empathize with women who have been forced into prostitution, many ofwhom are poor or indigenous themselves.

The Mexican soldiers also fostered an atmosphere of fear directed specifically at women. “They harass women when we walk by the barracks,” added Claudia. Dominga described something similar: “The women have always gone down to the stream to get water and firewood, but now with the presence of the soldiers so close to the stream, the women can’t go there anymore.”26

In addition to being harassed on a regular basis, indigenous women had a legitimate fear ofbeing sexually assaulted, as demonstrated by the case of three Tzeltal sisters who were raped by Mexican soldiers in June 1994. The three Zapatista women were detained at an army checkpoint outside of Altamirano and then gang raped by Mexican soldiers in the presence of their mother. The youngest of the three sisters was sixteen at the time.27 While this was the most well-known case, it was almost certainly not an isolated incident. The soldiers told the sisters they would be killed if they reported the rape. Zapatista women have heard about other similar cases that were never denounced. Given the many obstacles and systematic backlash that survivors of this type of crime face, it is not surprising that women would remain silent rather than turning to the Mexican police, and that many rapes have gone undocu-mented. Other known cases of rape were perpetrated by men who may have been paramilitaries or were not identifiable as Mexican soldiers.

The first half of 1998 was a period ofheightened state violence against Zapatista communities. From January to June, Mexican armed forces entered more than fifty Zapatista communities and “dismantled” three Zapatista autonomous municipalities (Ricardo Flores Magón, Tierra y Libertad, and San Juan de la Libertad) and one (Nicolas Ruiz) that was inspired by the Zapatista movement. During these military offensives, carried out by federal soldiers or the Seguridad Pública, hundreds of Zapatista civilians were beaten, arrested, and jailed; homes were illegally searched; municipal buildings were burned down; and property was destroyed and stolen. In the case of Ricardo Flores Magón, twelve international observers were detained and then deported. The violence peaked on June 10, when the Mexican military attacked three communities in the municipality of San Juan de la Libertad. In one village, seven young men were kidnapped by the Mexican army on their way to work in the fields and then executed. In another village, several more individuals were shot and killed as they fled from their homes and tried to escape into the mountains.

In the face of this violence, women organized to confront the Mexican armed forces. Forming a barrier with their bodies, lines of women blocked soldiers from entering their communities, sometimes physically pushing them back, and sometimes armed with sticks or rocks. At countless protests and confrontations with the army, chants of “¡Chiapas, Chiapas, no es cuartel! ¡Fuera Ejército de él!” (Chiapas isn’t an army barracks! Army, get out of here!) rang out. Insults were hurled at the soldiers, the women’s voices carrying the pent-up rage of four years of low-intensity conflict. Tiny indigenous women successfully drove heavily armed soldiers out of refugee camps, remote villages, and Zapatista strongholds. Faced with the women’s fury and determination, the soldiers did not know how to respond. Many times, confused and startled, they turned on their heels and fled.

Radical social movements must be able to defend their gains, and a willingness to engage in armed struggle can translate into a high level of militancy. The EZLN is an insurgent army that has not used violence since 1994, and it is often said that words have been the Zapatistas’ most powerful weapon. Their dual strategies of violence and nonviolence, however, are interrelated. To the traditional chant, “¡El pueblo unido jamás será vencido!” (The people, united, will never be defeated), the Zapatistas often add, “¡El pueblo armado jamás será callado!” (The people, armed, will never be silenced). Being an armed movement has lent the EZLN’s creative strategies of nonviolent resistance a particularly fierce edge. The Zapatista women’s actions of standing up to the Mexican military are an example of defending themselves and their communities, militantly, but without using guns.

What follows are the stories of just a few of the Zapatista communities that were attacked in 1998. In many cases, women were able to successfully drive the military out of their villages and prevent violence and destruction from being inflicted upon themselves and their families. Mixed in with these stories are descriptions of brutality, and not all of them could be considered “success stories.” Regardless of the outcome, all the women’s actions contained an underlying spirit of bravery and determination.

On New Year’s Day, 1998, the Mexican army occupied Nueva Esperanza, a small village near Altamirano. I visited about a week later and Zapatista women from Nueva Esperanza described what happened. “On January 1 at around eleven in the morning, federal soldiers entered our community while we were celebrating the New Year and inaugurating our new basketball court,” they said. “Everyone was at the party when the soldiers arrived. They surrounded the village and all the houses, but we were able to get out and hide in the mountains. Since there was a lot of mud in the village, we weren’t wearing our shoes during the party and we had to flee to the mountains barefoot. We left everything in our houses—shoes, jackets, dishes. We left everything behind.”28

The soldiers stole, ate, or destroyed everything in the community. When I visited Nueva Esperanza, the two cooperative stores were completely empty. All that was left were wooden shelves and discarded soda bottles. In one of the stores, there was one bag of salt. The soldiers had killed and eaten people’s farm animals and the chickens from the women’s chicken cooperative. They had burned the books in the school and poured gasoline in the church, threatening to burn it down. “They scattered everything on the ground—the beans, the coffee, the rice, the corn—they threw it all away,” said the women from Nueva Esperanza. That food was meant to last the villagers until the next harvest. “They defecated inside the kitchens and poured gasoline in our water buckets.”

Word spread quickly and that very same day, Zapatista women from a dozen nearby communities gathered to confront the soldiers. At a regional women’s gathering a few years later, Zapatista women from neighboring villages described what happened. “There were women from this whole region,” remembered women from El Nance, one of the villages that rallied to defend their compañeros. “A few women from Nueva Esperanza came with us, but most of them didn’t want to because they were so frightened when the soldiers surrounded their community. There were a lot of soldiers. We showed up with sticks and we pushed the soldiers and we shouted at them, ‘Soldiers, get out!’” But the soldiers did not budge. “We tried to chase them out three times, but they refused to leave.”29

“We told them to go away, but they didn’t listen,” said a group of women from Puebla Vieja, another nearby village. “They shouted at us, ‘Go home. If you’re still here tonight we’re going to make you our girlfriends.’ We told the soldiers that the land belongs to the campesinos. But the soldiers began to threaten us. They even beat some of the women.”

“Later on, people from the human rights groups arrived,” continued the women from El Nance, “and the soldiers calmed down a little. Before that they were very aggressive. They pointed their guns at us, but we weren’t afraid.” The press arrived the following day and the army began to leave. “We were there all day and all night,” the women said. “We had to be on alert until they left. They left little by little. It took about a week before they were all gone.”

Although the women from neighboring Zapatista communities arrived after the soldiers had already occupied the town and could not prevent the havoc wreaked on Nueva Esperanza, this show of strength by women from the entire region demonstrated the Zapatista communities’ level of organization and solidarity. I saw another example of this solidarity in a Zapatista village called Nueva Revolución, several miles down a dirt road past Morelia. Members of this community had recently donated two hundred kilos of corn from their already poor harvest to the refugees in the highlands. The women there told me that they were organized and ready at a moment’s notice to go with their sticks and help defend Morelia; there were rumors that Morelia might be attacked imminently.

It came as no real surprise, then, when the army entered Morelia on January 3, 1998. A masked government supporter accompanied the soldiers and pointed out the houses of Zapatista leaders, which the soldiers proceeded to search. Soon after they had arrived, however, dozens of women and their children rallied to chase out about seventy soldiers. When I went to Morelia to find out what had happened, the women described the atmosphere of tension: the men from their community were still in the hills, they said, and were not coming back until it was safe. They also said they had nothing to eat because no one could leave the village to harvest corn or beans from their fields or to collect firewood. But they were not willing to leave their town unprotected. Yet what stood out more than the hardship was their sense of victory in having chased the soldiers out of their community. They had, after all, stopped the soldiers from ransacking their homes, and they related the details with a mixture of pride and glee. The soldiers don’t know how to walk in the mud, they crowed, and related how one woman gave a soldier a good shove as he left, slipping and sliding in the muck.

On January 8, Mexican soldiers tried to enter Morelia again, but were driven out once more by the women. The soldiers seemed to be acting under orders not to engage in direct combat with the Zapatista villagers. Presumably the Mexican government had calculated that the price for its public image would be too high. I went back to Morelia again a few days later, with a small group of journalists. When we arrived this time, we were met by a small cluster of women who had been chosen by their community to talk about what had happened. They sat on wooden benches in a large auditorium, waiting for the reporters who often turned up after this type of event in Zapatista territory. Women were becoming the face of Zapatista resistance. Ernestina, the regional coordinator who had helped lead the fight to ban alcohol, was the oldest woman in the interview and the one with the most political experience. Elida, much younger than Ernestina, was in her early twenties at the time. As she talked, she often stood up to rock the baby tied to her back with a rebozo (shawl).

Ernestina: We don’t want what happened on February 9 [1995] to happen again. We suffered a lot back then.

Elida: On February 9 we fled from our village, but we didn’t have anything to eat in the mountains.

Ernestina: The children were hungry. They all got sick, they had fevers. We don’t want that to happen again. We are not going to run away again. It’s better for us to stay and defend our community.

Elida: That’s what the women decided and that’s what we did on January 8. We weren’t afraid, we felt proud. “If they shoot at us,” we thought, “well, then, they shoot at us.”

Ernestina: We didn’t know ifwe would be able to chase them out or not, that’s what we were thinking. But in the end we were able to chase them away.30

Elida and Margarita explained why it was women who confronted the soldiers:

Elida: We are willing to defend our village and to protect the men, because if they arrest the men, they will be killed or tortured, like what happened on January 7 [1994] when they killed three of our compañeros. We don’t want that to happen again. We don’t want any more deaths.

Margarita: They took the three compañeros away and killed them, and they took the rest of the men to Cerro Hueco [prison]. That’s why the women began to organize, because we have seen that when the army comes, they take the men away. Ernestina explained that on January 3, the soldiers left their trucks down the road, so no one had heard them entering the community. “After that, the women from Morelia set up a checkpoint to chase the soldiers away.” The women maintained this round-the-clock checkpoint for several days. Margarita said that on January 8, when the soldiers returned, they left their trucks on the dirt road at the entrance to the village.

Ernestina: We drove them out. We threw rocks and sticks at them. We shouted that we don’t want their handouts. We followed them more than two kilometers down the road toward Altamirano to make sure they wouldn’t pull one of their dirty tricks and come back to our community.

Elida: The children understand too. Like my children, they said, “They’re going to kill my father. If they take him away, they’re going to kill him, that damn soldier.” That’s what my children said.

Rosalinda, a ten-year-old girl, chimed in proudly: I hit one of the soldiers and I yelled at him, “You son of a bitch, you’re not going to come and kill my father!”

On the other side of a mountain range, in the Garrucha canyon, Mexican soldiers tried to enter a village called Galeana the very next day. A small community high in the mountains, Galeana was likely singled out because it is a known Zapatista stronghold. To get there you have to navigate a steep, rocky walk into the mist, and it is hard to believe there is a village up there until you get to the peak, the last resting spot, and peer down into Galeana with its bright yellow adobe houses nestled in the mountains. Representatives of the women’s cooperative store in Galeana had been participating in our regional workshops in La Garrucha, but I visited the village of Galeana for the first time not long after the confrontation with the soldiers. Visitors were rare and children came running out oftheir houses to crowd around my colleague and me.

Everyone was eager to tell us how they chased the army out. They knew the soldiers were coming up the mountain path, they told us. They were angry at the carelessness with which the soldiers trampled their cornfields and ate their sugarcane. “Nos cuesta mucho sudor” (It was hard work), they said.31 When the signal was given, they all rushed down the mountain to chase the soldiers away. They described in detail how big their sticks were and what they yelled: “¡Fuera Ejército! ¡No queremos dispensas!” (Get out, army! We don’t want your handouts!).

I asked if they had been scared. “Of course not,” said one young girl, but the boys tattled on her and said that she had started to cry. One of the women’s favorite stories was about a soldier lying and saying he had been bitten by a snake when, in reality, another soldier had shot him in the foot. Several soldiers were hiding, they said, too frightened to come out. Another memorable story was about a panicked soldier who could not untangle his radio line from the bushes—he had to ask one of the Zapatista women to cut the cord so he could leave the radio behind. “We chased them all the way down to the road,” the women said proudly.

It was, perhaps, a small victory in the ongoing battle between the EZLN and the Mexican government, but for the villagers in Galeana, it felt like a real success in the face of Mexican military might. News traveled quickly throughout the region and other women referred to it as an example. Doña Manuela, the Tzeltal elder from La Garrucha, talked about the women from Galeana chasing out the soldiers, and her eyes sparkled as she spoke. Known for her sharp tongue, it is not always clear whether Doña Manuela’s eyes are lit up with laughter or anger. “Those first days of January, we were ready,” she said. “We even had our sticks ready. We were all prepared, all the women with our sticks, just like the women from Galeana.” She stood up to demonstrate, and the stick was almost as tall as her small body, with a sharp point carved on one end. She shook the stick as if at a soldier. “But they haven’t come here,” she concluded. “I think they were afraid.”32

The Mexican army continued to threaten, harass, and attack Zapatista communities on a regular basis for the next several months, and to use increasingly violent tactics. The Seguridad Pública, the state police known to be more brutal than the Mexican army, entered the village ofDiez de Abril on April 14, 1998. Diez de Abril was named for the date, April 10, that Emiliano Zapata was assassinated in 1919, and the community remembers this occasion every year. During the festivities in 1998, there were already rumors of an imminent attack.

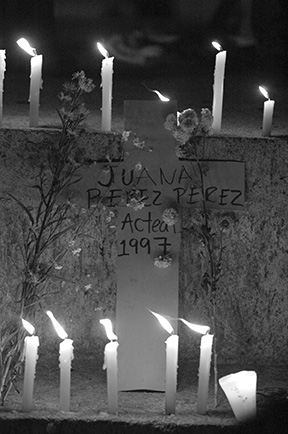

Zapatistas from the village of Galeana face off with Mexican soldiers. (Photographs by Tim Russo.)

“All the women went with our sticks to keep them from entering our village too quickly,” recounted Zapatista women from Diez de Abril at the women’s gathering in Morelia. “We had to be brave. We knew ahead of time that they were going to attack our village, that’s why we weren’t afraid. We organized ourselves well so we could defend our community. When we got there, we were prepared to die if they shot at us. We were yelling at the soldiers and asking them why they are doing this work of killing indigenous people when they are indigenous too.”33

In spite of the women’s courage, however, the Seguridad Pública escalated the violence, pushing the women back. “They shot into the air to scare us but even then we did not retreat,” the women continued, “not until they started hitting us. They started using teargas at our roadblock near the entrance to the village. We stayed there because two women were lying on the ground. We had to help them and several other women were also affected by the teargas. They detained a young man, and several women tried to stop the Seguridad Pública and free this compañero. The women who tried to rescue him were beaten.” The young man who was detained was seventeen years old. He was taken to Altamirano and tortured. After he was released, he described what is now commonly referred to as waterboarding—repeatedly being held underwater until he thought he was going to drown.

“When they entered the village, they went into every house to destroy our belongings,” said the women from Diez de Abril. “They took whatever they found, even the food. We all suffered afterward because there was no food to eat. We abandoned the village and went to the mountains, and we stayed there all night. We had to stay out in the rain. It rained all night. The children suffered the most because they were hungry.”

Although they were unable to stop the aggressors, the women were strategic in their defense. “The young women kept facing off with the Seguridad Pública as they advanced toward the village,” the women explained. At this point, the young women were just trying to buy time. “Meanwhile, the older women went back and got the children out of the village, so when the Seguridad Pública got there, all the children were gone.”

By the second week of January 1998, the EZLN had started to organize massive protests against the massacre in Acteal and the military incursions into their communities. Several other indigenous and campesino organizations joined the EZLN to protest the paramilitary violence and state repression. January 12, the fourth anniversary of the cease-fire in 1994, was a national and international day of protest. There were marches all over Chiapas, but the march in Ocosingo was one of the largest. As the demonstration wound to a close, thousands of people marched past the Seguridad Pública base on the outskirts of Ocosingo and anger flared up on both sides. Members of the state police fired teargas, people started running, and with no warning, the police opened fire. Most fired into the air, but a few fired directly into a crowd of people only a few yards away. Three people were shot and wounded: a young man, a young woman, and the woman’s two-year-old daughter, who had been in her arms.

I arrived in Ocosingo a few hours later and accompanied the protesters, who had decided to march back to the central plaza of Ocosingo and camp out there. There were speeches, and then music and dancing. We were still dancing when the announcement came that Guadalupe Méndez López, the twenty-five-year-old Tzeltal woman who had been shot by the Seguridad Pública, had died in the hospital. There was a collective murmur of shock and sadness, and then a moment of silence. The tragedy did not stop the women from being hospitable on that cold night; one woman insisted that I lie next to her on her sheet of plastic and share her thin blanket.

Two days later, the protesters were still gathered in the plaza. I bought tamales for some of the women because I knew they had not eaten. Around midday, the Zapatistas divided into three groups—one to block the highways, one to take over several public buildings, and one to go to La Garrucha for Guadalupe’s funeral. I joined the group going to the funeral, but went to say good-bye to the people I knew first. I found them in the contingent preparing to block the highways. As they marched off to protest the death of their compañera, their backs were straight, their heads were high, and their faces were strong and serene. You would never have guessed that these same women had just been telling me how much their children missed them, and how tired they were from sleeping in the plaza.

I then climbed aboard one of the Zapatista trucks going to La Garrucha. There were dozens of people standing in the back of the truck and they told me to squeeze into the middle so I would not be seen when we passed the immigration checkpoint. The ride was dusty and bumpy and uneventful until we got to the army base next to La Garrucha, where the soldiers stopped us. All the Zapatista men were told to get out of the truck and searched. I stood in the back of the truck with the rest of the women, and was only subject to curious sidelong glances from the soldiers as they searched the bags.

At the funeral, hundreds of Zapatistas marched in formation behind the coffin, up the dirt road and then off the road into the fields, past the army base, and into the cemetery. The mood was solemn as we entered the cornfields surrounding the cemetery, and the mass of people became a single-file line winding its way along the narrow path through the dry corn. When we arrived, the women clustered around the grave while the men sat behind. As fresh dirt was shoveled onto the grave, a keening, crying, singing expression of grief emerged from the women. It went on for a long time as Guadalupe was buried.

On the way back to La Garrucha, there was a terrible finality of returning without the coffin. As we passed the army base, the collective fury spilled over. Maybe they were taking advantage of their strength in numbers to make up for all the times they had been afraid to go to their cornfields, to get water or collect firewood, to go out at night, to walk by the army base alone. Or maybe they were so mad they didn’t care. They marched straight to the base and chanted and yelled and waved their fists and let out all the rage, grief, and terror that had accumulated for days and weeks and months. Then they marched through the base and back to the road, right past the spot where the army had been stopping vehicles and searching people just a few hours earlier.

Guadalupe Méndez López’s funeral procession. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Midwife and respected elder Doña Manuela was at the funeral that day. Like the other mourners, she had a red bandanna covering her face, but that tattered cloth couldn’t hide who she was. She led the women placing flowers on the grave and, when we arrived at the army base, she was up at the front, screaming and shaking her fist. “When we went to bury our compañera, I was jumping up and down, I was so mad,” she said later. “We don’t want the army here, damn it. I’m not afraid, you know? Ifthey want to kill me, well, kill me, here I am.”34

Guadalupe Méndez López, whose little girl survived, is considered a martyr by the Zapatistas, and many Zapatista women especially identify with her. Years later, during an International Women’s Day march, a young Zapatista woman from Diez de Abril shared her thoughts with me.

I was at the march in Ocosingo when our compañera Guadalupe was killed. I was there for three days. I think it’s important to march for women who have given their lives, who have done their work and carried the struggle forward. [International Women’s Day] is their day—the women who have died for the struggle. I thought a lot about compañera Guadalupe, who died on January 12, 1998. I was thinking that I would like to die like that too—die fighting. It’s important to march so as not forget those women.

One of the goals of low-intensity conflict is to wear people down. In addition to overt violence, the psychological pressure included persistent rumors and false alarms. People knew the army might turn up at any moment. In some places, community members would stand watch every night on the road to protect their village. And while counterinsurgency tactics have certainly taken a toll on the Zapatista support base over time, in 1998, the military offensives against Zapatista communities seemed to have the opposite effect. It seemed like every attack only made them angrier, more righteous, and more determined.

While it was a time of tension and fear, it was also a time of euphoria and adrenaline. There was an unmistakable feeling that the Zapatistas and their supporters were winning. And looking back, I do think the Zapatistas “won,” especially since so much of the terrain of the Zapatista struggle has been in the public sphere, in the realm ofideas, and in their image in the eyes ofMexican and international society. In addition to winning the moral high ground, the Zapatista support base emerged from those six months of violence stronger than before. And for the women involved, their overall tone when talking about this time period was one of defiance and pride.

These events had a far-reaching effect on the public discourse that surrounded them. One of the most famous images from that time period is ofan indigenous woman shoving an armed Mexican soldier. Startled, the soldier looks like he is about to fall over backward, in spite of the fact that the woman barely comes up to his shoulder. The photo was taken in the refugee camp of X’oyep, when the Mexican army attempted to establish a base and about two hundred women and children from the organization Las Abejas surrounded the soldiers and forced them out. This image captured the spirit of unarmed resistance carried out by the indigenous people of Chiapas. And, although this photo is not actually of a Zapatista woman, the image came to symbolize the Zapatistas’ struggle ofthe small against the powerful. This and other images of indigenous women standing up to the Mexican army and chasing soldiers out of their communities had a powerful impact on the collective imagination in Mexico and around the world, and challenged many preconceived notions about rural, indigenous women.

A woman in the refugee camp of X’oyep pushes back a Mexican soldier. (Photograph by Pedro Valtierra/Cuartoscuro.)

The Mexican government accused the EZLN of ordering women to confront the soldiers and using them as cannon fodder. This claim ignores women’s agency in these actions. Others argued that they were spontaneous actions, and that women simply decided to respond this way in village after village. This theory overlooks the fact that Zapatista women belong to a militant political organization that had developed a coordinated and well-organized response to ongoing attacks.

The decision to confront the army was part of an organization-wide strategy, but was affirmed in each Zapatista community or region and then carried out with creativity, improvisation, and initiative—usually by women and sometimes by men and women together. During the collective interview in Morelia, Elida talked about the process of readying themselves for a potential attack. “The women had a meeting,” she said, “because whenever the soldiers come, there are always rumors ahead of time, and we talked about how to chase them out. We said that we were going to shout as loudly as we can and push them back. That’s what we talked about and, when they came here, that’s what we did.”35 I had numerous other conversations with women who described community meetings to organize their response if the army should attack their village, and these women consistently talked about themselves as the protagonists in organizing these actions.

Agreeing with the decision to confront the army does not mean the women were not afraid. But the women were afraid of the soldiers anyway, and of what would happen if the army attacked their village. So their fear did not stem from the decision to stand up to the soldiers. Given a situation with great potential for violence and destruction no matter what they did, the women faced their fear and chose to respond in a way that, in many cases, minimized the violence inflicted by the armed forces. When the women from Diez de Abril said they were not afraid because they knew ahead of time that their community was going to be attacked, I don’t think they meant that they literally felt no fear. What I understood them to be saying (in addition, perhaps, to showing a little bit of bravado) was that this knowledge allowed them to be mentally and physically prepared and to steel themselves for the confrontation.

The original reason that women were on the front lines was the assumption that the Mexican army was less likely to respond to women with force, and women were therefore less vulnerable and more able to drive the Mexican soldiers out. During the interview in Morelia, Elida and Margarita cited previous incidents where men had been killed, tortured, or arrested, and expressed confidence that their actions, as women, would reduce the likelihood ofviolent reprisals from the army. I heard this explanation from Zapatista women over and over during that time period.

A mural in La Garrucha reproduces a well-known image of a refugee woman pushing a Mexican soldier. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

By challenging gender roles in communities in which men were traditionally seen as protectors, Zapatista women altered how they saw themselves and how their communities saw them. By challenging stereotypes about women in general and rural women in particular, they also shifted the relationship between indigenous communities and the Mexican government. The women involved gained an incredible sense of their own strength and power. In addition to protecting their villages from the Mexican military, imagine what it must feel like to face dozens, sometimes hundreds of soldiers, often in riot gear and wielding guns and batons, and have them turn tail and run. Women’s perceptions of themselves changed; this then allowed them to take increased initiative and leadership in other spaces.

Celeste, the widow whose husband was killed in the uprising, has been actively involved in the Zapatista movement as a health promoter and as a local and regional coordinator. “Before 1994,” she said, “we had never seen a woman participating, or a woman who left her village to go anywhere else. In some communities, where the soldiers attacked us in 1995, a lot of women protested. We spoke up, we organized against the soldiers. The women found the courage to defend ourselves and our communities. After that, women started to participate in other ways too, because we felt stronger.”36

Men’s attitudes toward women in Zapatista communities shifted as well. Men who had previously been reticent about acknowledging women’s rights could no longer deny that women had an important role to play in the movement. How could they maintain that women should have no voice in a community assembly, for example, when it was women forcing the military to retreat? The men saw women, although sometimes grudgingly, with new respect and admiration.

In one village, for example, one of the local male representatives had consistently forbidden his wife from accepting any level of public responsibility. On a number of occasions, the women had nominated her as the coordinator of the women’s cooperative store, and her response was always, “My husband won’t let me.” This impacted the entire community, since he was in a position of leadership and was seen as providing an example. After his wife, along with the rest of the women from their village, mobilized to drive the soldiers out of their community, he no longer stood in her way. She told me that his attitude had shifted but that she had also become more insistent about her right to participate in activities outside the home. Shortly thereafter, she became one of the coordinators of the women’s cooperative and, in the following months, there was a small but noticeable increase in women attending and voicing opinions in the community assembly.

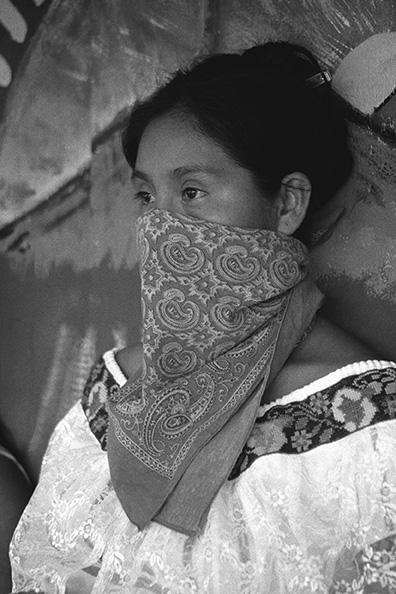

A Zapatista woman’s pensive gaze. (Photograph by Paco Vasquez.)