Julia, who is now a Zapatista comandanta, was orphaned as a young child. “My mother died from illness when I was six months old,” she told me, “and then my father died from drinking too much. I grew up with my older brothers but they used to leave me alone on my father’s land to take care of the animals for a month or two at a time.”1 When she was ten years old, Julia went to live with her aunt. “I saw that if I stayed with my brothers, I was going to suffer more,” she recalled. When Julia’s sister was thirteen years old, she was married to an older man against her will, and Julia wanted to avoid that fate. “After that, I went to stay with the nuns at a school for indigenous girls in San Cristóbal,” she said. She wanted to study and then go back home to help other women, she explained, because by the time she was ten years old, she had already seen the difficulties women face.

Julia joined the EZLN in 1995, when she was already in her forties, and a few months later was given her first public position. A tiny, energetic woman, she was one of the coordinators who accompanied me throughout her region. We would travel together from village to village, walking and talking for hours at a time. Every morning, Julia would ask me what I had dreamed the night before and would usually offer an interpretation. One day, we came across a wounded dove in the path. Julia picked it up and carried it with her all the way home, where she nursed it back to health.

Comandanta Julia often talked about another woman, Olga Isabel, with great affection and respect. “She was the first regional women’s coordinator from this area,” Julia said. “I became a regional coordinator later and I learned how to do the work from her. She always counseled me. I had a difficult time but she would tell me, ‘You have to get through those problems. We have to deepen our organization, we have to be conscious in our work and make our struggle stronger.’”

Of all the Zapatista women who have exhibited great courage and leadership, the compañeras caídas—women who have given their lives to the struggle—occupy a special place in people’s hearts. Olga Isabel, who died in 1998, was never a national or international figure. She was beloved in her own region, however, and is deeply missed by those who knew her. During a collective interview in the autonomous municipality named after her, a group of several dozen Zapatista women recounted their memories of her. For many of the women who had known her personally, it was an emotional, sometimes tearful conversation.

We want to honor our compañera Olga Isabel, because her work, her path, her organization are still alive. She joined the organization in 1994, together with her parents and her brothers and sisters. When she joined the organization, she devoted herself with her whole body and soul, to see how far the struggle could go and how it would change the world.

First she became the coordinator of the women’s cooperative. She took a course for the cooperatives’ coordinators. Each time she returned from a workshop, she called a meeting to share what she had learned. She told us how important it was for us to organize. She began organizing women’s cooperatives. She organized the bread-making cooperative and then a collective bean field. Not all the women wanted to participate at first, but when they saw us harvest and distribute the beans, and that we had more food to eat, the rest of the women wanted to join the cooperative too.

Olga taught us what it means to struggle. She explained to us how to organize as women. She always spoke well and gave us good advice. She was very patient. She always went to meetings, even if the path was full of mud and it was hard to walk. She was never afraid and she was an example for us. Her work is still alive because we continue the work that she started.2

After working with women’s cooperatives for less than a year, Olga Isabel was asked to become a regional coordinator. She held that position for three years before she died.

Located in an isolated area in northern Chiapas, this Tzeltal region still has few paved roads, and Julia and Olga Isabel used to walk together on dirt paths from one village to the next. “One time there was a meeting here in the municipal seat because there was a problem in one of the villages,” Julia recalled. “They didn’t want to continue on anymore. They wanted to leave the organization. Two men and two women went to speak with them, and Olga Isabel was one of them. She told the compañeros not to abandon the struggle, that they should keep moving forward. They stayed in the organization and they still continue today.”3

Comandanta Julia, who now plays the role that Olga Isabel once did in organizing and inspiring other women, was the last person to see Olga Isabel alive. “We were on our way to the seat of the autonomous municipality for a meeting of all the local and regional authorities, men and women,” Julia explained. “She died on the way to that meeting. As we walked, we were talking about how to organize the women more. While we were crossing the river, at around two o’clock in the afternoon, her foot slipped and she fell into the river.”4 Olga Isabel fell into the water on October 15, 1998. A search party looked for her but her body was not found until the morning of October 17. She was twenty-three years old.

Olga Isabel has not been forgotten. “Whenever I got discouraged,” her sister recalled, “Olga would always tell me, ‘We have to keep going.’ I am a local representative and I don’t always go to the meetings because of my children, but she always encouraged me. I dream about my sister Olga. She still comes to visit me in my dreams.”5

“Olga never worried much about her own housework,” said Ruth, who has six children, eight grandchildren, and is a member of the autonomous Honor and Justice Commission. “She was more preoccupied with her work with the compañeros and in the municipality. We have monthly gatherings and we don’t always go because we have other work to do. But when we don’t go, it’s as if we’re ignoring what Olga used to tell us. When Olga was still with us, she was present at every meeting. Sometimes we forget Olga’s example but we should not continue this way. Even talking about Olga’s example right now, we feel motivated again and we’re going to follow in her footsteps.”6

Olga Isabel is an example of a Zapatista woman whose commitment and enthusiasm inspired countless other women to organize. Julia explained how they decided to name the region after her. “They told us we needed a name for our autonomous municipality,” she said. “We had an assembly here in the municipality to talk about it. All of us were looking for a name, thinking about our own history. And we thought, ‘Why don’t we name it Olga Isabel?’ Because Olga had passed away, she was a strong compañera, she was an example for us, and that way her memory will never be lost.”7 The autonomous municipality Olga Isabel has an anthem, which includes the following lines:

| La compañera Olga | Compañera Olga |

| vive en el corazón | lives in the hearts |

| de todos los que luchamos | of all those who struggle |

| en la organización. | in the organization. |

| En su nombre hay | In her name there is |

| todo un municipio | an entire municipality |

| que luchamos como ella | of people who struggle like |

| por nuestra libertad. | she did for our freedom. |

The women organized to form a cooperative and we began to see that women can also participate in meetings and assemblies. From there we started thinking, little by little, about how we want our lives to be. We want to change all those ideas that have been put in our heads for the last five hundred years. So we organized and now women participate more, now they can leave their houses. Even if they have children, they can leave the house for a while and go to a meeting or a women’s gathering, help out with the women’s cooperative, or go to a health workshop.

—COMANDANTA MICAELA8

The Zapatistas’ structure of political leadership and internal decision making was created when the EZLN was still a clandestine organization. The first responsables, as they were called, were part organizer, part messenger, and part leader. As organizers, they recruited other community members into the EZLN. As messengers, they maintained communication between the Zapatista army and the support-base communities. And, as the Zapatista villages became increasingly cohesive and well organized, they began coordinating different aspects of village life. At the beginning, most of these responsables were men. As the Zapatista organization grew and consolidated, this structure expanded to include regional coordinators as well as local representatives. The regional coordinators oversee all aspects of the Zapatista movement at the regional level, including political, economic, social, and cultural affairs.

Assemblies became a key element of this structure. Open to all adult members of the village, each community assembly makes local decisions and chooses local authorities. The regional assembly brings together all the local representatives from a given area to discuss regional concerns and select their authorities. Local representatives also act as messengers to and from the regional assembly. When they return from a regional meeting, for example, they convoke a local assembly to share any relevant information, decisions that were made, and proposals the community needs to discuss. A well-respected local representative is often promoted to be a regional coordinator.

At the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, a Zapatista woman from La Realidad described her role as a regional coordinator.

It’s our responsibility to organize the communities and encourage them. We visit the villages to see how the cooperatives are doing, to see if they are doing well or if there are any problems. If one ofthe cooperatives has failed, that’s not a reason to give up. Quite the opposite—we put our heads together, the coordinators and the community members, to look for new alternatives and ideas to keep moving forward. We work together to solve problems. When something has gone well, we share this information with the coordinators from other regions.

We also organize marches and sit-ins. If they try to kick us off our land, we organize ourselves immediately. We organize how many men and women will go and defend our communities. We also organize parties to commemorate certain dates, like March 8 [International Women’s Day], which is a significant date for Zapatista women. Men and women, children, young people, and elders all participate in these parties with songs, poetry, speeches, traditional dances, skits, and riddles.9

The EZLN’s highest body of political leadership is the CCRI and individual members of the CCRI are called comandantes. The CCRI was formed in early 1993 to replace the nonindigenous leadership of the FLN when the decision was made to go to war. Because they are called comandantes, outsiders often mistakenly think members of the CCRI are part ofthe EZLN’s military hierarchy, but the comandantes are civilians—they are the Zapatista movement’s political leaders. After proving him or herself, a skilled regional coordinator might be promoted to the CCRI by the regional or zone-wide assembly.

The word participar (to participate) has wide-ranging implications in this context. When Zapatista women say, “Now women participate,” they are expressing that women have rights, that they have a voice. In addition to holding positions of public responsibility, they use it to mean any kind of involvement in community affairs or political activity. Women often talk about the right to participate in meetings and gatherings, for example. For the indigenous people of Chiapas, community assemblies have historically been an important institution for making collective decisions about anything impacting the whole community. These assemblies are held in any available communal space: the church, the school, or in an open-air structure with a thatched roof and wooden benches. Discussions are informal and can be long, because everyone has the right to speak until an agreement is reached. In the past, however, women rarely attended community assemblies. When women say they have the right to “participate” in these meetings, it means being physically present, as well as speaking up and voicing an opinion. It also implies that their opinions will be heard and respected.

Women emphasize their participation in the EZLN because this transformation took place within the Zapatista movement, and because the EZLN has become so deeply integrated into the indigenous villages in its territory and many aspects of people’s lives. Local and regional assemblies are now Zapatista meetings. For the Zapatistas who farm on occupied ranchos or fincas, their land is Zapatista land. Zapatista cooperatives are the backbone of the local and regional economy. Once the autonomous government and systems of health care and education were up and running, these too became Zapatista infrastructure. Participation in the Zapatista movement therefore encompasses women’s involvement in public affairs and political life in general—community decision making, health and education, government, and so on.

The women from Morelia explained that it is still hard for some women to accept public positions. “Many women think they don’t know anything,” they said, “but that’s because before, women never had an education. But when you accept a position of responsibility, that’s where you begin to learn. You learn to do the work, how to resolve problems, how to speak up. It takes time, but all of a sudden, almost without realizing it, you begin to speak up in meetings and assemblies.”10

At the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, Everilda, an alternate member of the CCRI from La Realidad, explained how she arrived at that position of authority.

I began as a member of the support base when I was ten years old. I was a member of the support base for two years and seven months, participating, working with my community. Then the men and women of my village named me as the local representative, to work side by side with my community, supporting the cooperatives and other types of organizing. I also brought political information back from the regional meetings. I did that work for a year.

Then I was chosen by the local representatives from all the villages in my region to be a regional coordinator. It’s more work, because you are responsible for leading all the villages in your region. You also participate in the zone-wide meetings, to learn about the national and international situation and the internal plans and circumstances of the EZLN, and then share that information with the local representatives. I did that work for more than seven years.

Then I was elected as an alternate member of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee by the regional coordinators from the different regions. They saw my participation in the meetings, my political consciousness, and my willingness to work on behalf of our organization. This proposal was also accepted by the military commanders of our Zapatista Army of National Liberation. Being in this position comes with much greater responsibility, because you are coordinating several regions at the level of the whole zone. To get to this point, you have to do this work for many years. As alternate members of the CCRI, we participate in the meetings of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee. We help to maintain and nourish the spirit of struggle of our compañeros and compañeras.

It is our communities that have taught us to struggle fiercely and with courage. We respect the people and the people respect us as their representatives. They correct us when we make mistakes and we correct their mistakes as well. Within our struggle we practice three very important things: unity, discipline, and compañerismo. In this work that we do as part of the struggle, we push ourselves to learn, to better serve our people.11

None of the Zapatista authorities are paid; holding a position of public responsibility is seen as a way to serve your community. They are, however, supported in other ways. A local representative from La Realidad explained:

When the local representative goes to the regional meetings, the women make an agreement to support her by paying her bus fare. We have to travel more than eight hours to get to the meetings, sometimes up to twelve hours, and the meeting lasts for two, sometimes three days. The community makes an agreement that the women will support this person by taking care of her children, washing the clothes, donating tortillas to her family, carrying firewood for her house, and her husband also helps out by taking care of the house, the children, and the animals.12

Men and women authorities have the same overall responsibilities, but women have the additional task of organizing specifically with other women. “Some communities have a women’s coordinator,” said Ofelia, a Zapatista woman from La Garrucha. “This woman has to be a real leader because her responsibility is to organize the rest of the women, organize the women’s cooperatives, and resolve any problems that arise. She has to explain to other women that they can participate, and the different community projects they can be involved in. The structure of women’s representatives was organized by the EZLN and has been around since before 1994. Before 1994, some women participated but only a few. After 1994, more women began to participate.”13

The EZLN’s insistence on women’s participation in the movement created opportunities for women to play new roles and led to greater consciousness about women’s rights in general. But for many years the EZLN worked to incorporate women into its organization without an explicit analysis about gender and with no strategies to address patriarchy. Describing the EZLN’s perspective toward women before 1994, Esmeralda said, “It was all about the struggle, women’s participation in the struggle. Women could learn the same things as men; they could organize; they could become insurgents.”14 Like many other Marxist formations, the FLN’s approach to gender discrimination and violence was that women should join the movement. In its early years, the EZLN adopted this approach as well. The revolutionary struggle itself was the central focus and the accompanying analysis was that women’s liberation would be achieved with the triumph of the revolution rather than by addressing patriarchy as a distinct system of oppression. And like many other radical and revolutionary social movements, in spite of strong rhetoric about women’s rights, sexism within the movement presented a real challenge.

In 1995, the EZLN’s leadership wrote a pamphlet called Compañeras, participa en la lucha revolucionaria zapatista (Compañeras, Participate in the Zapatista Revolutionary Struggle) and circulated it among the support-base communities. The title is indicative of its central message. The first half of the pamphlet lays out the history of discrimination and oppression that women face “in the home, in the community, everywhere; in government institutions, and even in the church.”15 It addresses all women who “have never had the right to speak up or participate in decision making” in the political sphere, and talks about discrimination in the domestic realm.16 The document acknowledges that women do not have the right to educa-tion or to own land, and suffer the most from economic exploitation and the lack of medical care. After a comprehensive description of the problems, however, it proposes one solution: “That’s why it’s necessary for women, together with men, to participate in the organization and struggle together.”17 The second half of the pamphlet makes the case for women’s full participation in the revolutionary movement. Although the pamphlet is primarily directed at women, when it addresses men, it asks them to encourage their wives and daughters to take on responsibilities within the movement.

The EZLN undoubtedly found it necessary to make the case for women’s participation to counter men’s resistance and to establish it as a basic right. Nevertheless, the failure to propose any solutions aside from women’s participation in the struggle demonstrates the lack of complexity in the EZLN’s gender analysis at that time. There is no discussion about how to end violence against women, how to address economic inequality, or how to lessen women’s workload at home, and this limited focus constrained the Zapatista movement’s ability to confront patriarchy. Esmeralda speculated about how the EZLN’s work with women during its years as a clandestine organization might have been different.

If we had had a gender perspective, I think we could have advanced much more. Because yes, we did a lot of work with women and women began to participate more. They were given political training and those who didn’t know how to read were taught to read and write, and to speak Spanish. I remember the organization made a literacy manual back then. I still have it somewhere; it was one of the few things I didn’t burn in 1994. [laughs] All that was promoted by the organization.

But I think we could have done things . . . I think they could have been better planned and with more vision. We could have done more. If we had had a gender perspective back then, the work would have moved forward so much more—it would have been incredible. But we didn’t. Not even of women’s rights—just the right to participate, but without any vision of gender.18

The EZLN proved able to change over time and would later develop a more nuanced gender analysis. “There are many things within zapatismo that helped this process,” said Esmeralda. “The level of political organization, the consciousness, the search for autonomy, and the desire to change.” And, regardless of its limited gender analysis in its earlier years, the Zapatista movement succeeded in creating leadership opportunities for women. As we have seen, with this increase in political participation, women achieved a series of other transformations in their lives, their families, and their communities. “In the organization we have found solidarity between men and women,” said a group of Zapatista women during a collective interview in Olga Isabel. “Now that we know women have rights, the men help us out in the kitchen a little bit, and we have more time to rest. Now women know that we deserve respect. We have the right to go to school and to decide how many children to have. As women it’s our obligation to keep moving forward and make sure that we never go back to being mistreated like we were in the past.”19

Organizing in the cooperatives is where women first began to understand that we have rights. Working together collectively is a way /or us to support each other, and to help the community.

—Zapatista women from the Morelia region20

When we began working in Zapatista communities, my colleague and I knew we wanted to collaborate with women’s cooperatives. In addition to facilitating economic development, we understood that these cooperatives were a building block for women’s participation in the Zapatista movement. Throughout this movement’s history, women’s cooperatives have created an environment where women can learn about their rights, confront internalized obstacles, and begin to voice their opinions. Comandanta Micaela, one of the regional coordinators with whom we frequently consulted, once said, “When we’re in a group of all women, working in the cooperative or at a women’s meeting, all the women feel comfortable speaking up. But when the men show up, or when we’re in a community-wide assembly, the women are silent. They feel afraid again. The women’s cooperatives help because it’s a space just for women. That’s why the women’s cooperatives are so important: so women can learn to speak up first among ourselves, and so we can help the women who are still afraid.”21

What was less obvious to us was what exactly we could offer as outsiders. Something I deeply valued about my time in Chiapas was the dialogue we had with Zapatista authorities—the brainstorming and strategizing we did about our project while at the same time having clear systems of accountability to the Zapatista leadership and to the communities themselves. So we spoke with the regional women’s coordinators about how we could best support the women’s cooperatives and they proposed that we teach math and accounting to the cooperatives’ representatives. At first I was startled. I had not expected my contribution to this revolutionary movement—however humble it might be—to take the form of accounting workshops. I quickly came to understand, however, the importance of women being able to run their own cooperatives and the obstacles they faced, since most women had very limited formal education. My colleague and I would later joke about calculators and abacuses as unexpected tools for women’s empowerment.

In the Garrucha region, women participate less actively than in some other Zapatista areas, such as Morelia, where women have long been organized into cooperatives and almost every community has at least one such project. In the late 1990s, acknowledging this as a cause for concern, authorities in the autonomous municipality Francisco Gomez, part of the Garrucha region, initiated a project to provide small loans to villages that wanted to open a women’s cooperative store. At the time, these stores were the only women’s cooperatives in the region.

In each village that received a loan, the women’s assembly selected a group ofwomen to run the store. They usually chose young women who had gone to school, for a few years at least, and knew how to read and write, to be the storekeepers and administrators. The treasurer, whose primary role was to safeguard the money, was often an older woman trusted by the community for her integrity. Agustina, the Tzeltal woman who participated in the campaign to ban alcohol in La Garrucha in the early 1990s, was asked to be the treasurer for her community’s cooperative store. She explained that she began to participate first in the church, then later with the EZLN, and more recently with the women’s cooperative store. “I don’t feel as timid anymore when I participate,” she said. “I feel good because I used to be shy but now I’m not. Now I speak up whenever I want to.”22 Although Agustina could not read or write, her moral weight in the community was important for the store’s success. Agustina consistently encouraged the young storekeepers, telling them how critical it was for them to do this work.

I worked with these cooperative stores for several years, providing workshops for the women responsible for running them. The workshops lasted a few days each. We would practice addition and subtraction with dried beans and act out scenarios about how to run a store. One of us would walk into the “store” and ask for a bag of salt, a bottle of oil, and some chewing gum, for example. The storekeepers would practice adding up the prices and counting out the correct change, or, if we said we did not have any money and asked if we could pay later, they would write down how much we owed in a dog-eared notebook. After lunch, we would walk to the river together to bathe, and in the evenings, after the workshop was over, we visited the women in their homes to make a social call, or for more informal conversations about the work.

Agustina described the extraordinary transformations that took place during those workshops.

Not all women participate. It’s still very hard for them, especially young women, like the young women who work in the store with me. Sometimes they’re too timid to even say their names. But I have seen how much they have grown and changed. They begin to feel less embarrassed and then they begin to participate. It’s a beautiful thing to watch: they begin to speak up, to participate, and they know how to do their work in the store. Once women stop feeling ashamed and begin to use their voice, they feel ready to participate in other community activities.23

A collective vegetable garden in Ocho de Marzo. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

A collective bakery in Vicente Guerrero.

(Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

An artisan cooperative in Primero de Enero. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

A collective bakery in Olga Isabel. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

The young women Agustina spoke about were sixteen or seventeen years old. During the first workshop, it was often difficult to get them to say one word out loud. But by the last workshop these young women had conquered many of their fears. They still covered their faces with their hands in a gesture of shyness, and were more comfortable speaking in Tzeltal than in Spanish, but they were confident of their ability to run a small store and would come to the front of the room to demonstrate to each other how to manage the store’s inventory.

One of the project’s goals was for women to run the stores without any outside help. The administrator was responsible for the store’s accounting, which included some fairly advanced math and bookkeeping. Our training workshops sought to address women’s historically limited access to education, but in some villages there were no women who felt prepared to take on the responsibility. In those cases, the community asked a man to step in and do it.

Ofelia was the administrator of the women’s store in La Garrucha, and was more self-assured than the other young women in the group. Perhaps because members of her family had been involved with the EZLN since its founding, at seventeen she was one of the first women in her community to take on certain leadership roles. “When they name a woman to a certain responsibility,” she said, “they don’t ask if you know how to do this job or not. If they choose you it’s because they’re confident you can do the work. And if you don’t know how, you can learn. We like this because we have begun to participate in many community projects that we didn’t participate in before.”24 Tall and thin, Ofelia wore Western-style clothing that she sewed herself, and her long hair hung in a thick ponytail down her back. She began to accompany me on visits to cooperative stores in other communities, and was soon leading the workshops herself. Able to give the workshop in Tzeltal—which I could not—and incorporating humor into the activities, Ofelia was a much better teacher than I was, and she broke new ground for other women with her example.

Economic cooperatives were formed in some indigenous villages beginning in the 1970s with assistance from the Catholic diocese and later the Maoists. These cooperatives became a core element of the EZLN’s organizing strategy, and they have provided material support to the Zapatista movement for more than two decades. Men and women usually form separate cooperatives, based on a gendered division of labor. Men, for example, might have coffee or cattle cooperatives or collective cornfields. Some women’s cooperatives, like vegetable gardens and chicken-raising collectives, are geared toward local consumption, while others, such as artisan cooperatives, sell handwoven clothing and tapestries to an external market. The decision to form a women’s cooperative is made at a women’s assembly. Participants in the assembly decide what type of cooperative they want, choose coordinators, and discuss how to organize the project. Once the EZLN became a well-known entity, it was easier to secure solidarity funding to form new cooperatives. This was not the case, however, while it was still a clandestine organization. “We got a little money together,” explained Margarita, one of the women from Morelia who had helped drive away the Mexican soldiers. “Each woman donated a few pesos and that’s how we started the cooperative bakery. Each woman also donated a chicken and that’s how we started the chicken-raising collective.”25

Both before and after the uprising, the EZLN made a concerted effort to organize women’s cooperatives throughout Zapatista territory. At the women’s gathering in Morelia, a group of regional women’s coordinators recalled:

We visited different villages to support the women and encourage them to organize. If the women had not organized a women’s cooperative yet, we explained how to organize one. We went to one village on one visit and another village on the next visit. It was like a chain—we visited all the communities one by one. When the regional coordinators arrived, the local representatives felt supported in their work. For example, we visited a village called Mendoza. All the women in Mendoza gathered together. There was already a local representative, but they felt nervous about trying to start women’s cooperatives. After the visit, they formed a cooperative.26

The women’s cooperatives generate resources that are reinvested back into the community. Before 1994, these resources were primarily used to support clandestine activities, such as feeding the insurgents in the mountains. After 1994, the cooperatives began to respond more to economic needs in the villages. The income generated by the cooperatives might be used to pay for a cultural celebration, a political mobilization, to respond to emergencies, or to support community projects. “We invested the money in a small pharmacy,” said the Zapatista women from Olga Isabel. “The government never gives us health care and we don’t have money to go to the city and buy expensive medicines. That’s why we started this pharmacy, to help ourselves as a community by providing medicine at a low cost.”27

Women’s cooperatives benefit the community in other ways as well. “We work in a cooperative vegetable garden,” said Ernestina, “and when we pick the vegetables, we distribute them among ourselves. The cooperative garden is important because it’s good for us and for our children to have vegetables. Now our children are used to being able to eat vegetables.”28 Vegetable gardens and chicken-raising collectives were part of a strategy to reduce malnutrition among women and children. Cooperative stores, like the ones in Francisco Gómez, make basic goods available at a reasonable price without having to travel several hours to the nearest city. “The cooperative store helps us in many ways,” said the coordinators of the women’s store in La Garrucha. “We can buy the merchandise we want. The store loans money to the community and it helps us resolve any necessity that comes up.”29 Although these stores are Zapatista cooperatives, they function as regular businesses and are open to anyone in the community.

As women gain economic independence, they are able to exercise more control over their lives. “With the profit from the store, we would like to buy a corn mill to help women grind their corn,” said Agustina, “so we won’t have so much work to do at home.”30 Having a corn mill in their village can make a significant difference because women typically spend several hours a day grinding corn for tortillas. In some cooperatives, the women participating may receive a share of the profits. This is especially the case with artisan cooperatives, because each woman creates an individual product. And while the majority ofwomen’s cooperatives focus on responding to communal needs, in some cases the money generated goes to buy medicine for a woman who is sick, or is donated to widows in the community.

Zapatista women from the Morelia region explained that they also organized cooperatives so they could pay transportation costs for women to travel to meetings or workshops. “This is important so women can participate at the regional level,” they said. “Before, when there was a regional meeting, everyone had to chip in. Everyone would give three or four pesos. We saw how difficult it was to come up with the money, so that’s why we organized the cooperatives. Now the men don’t have to support us.”31 Especially in more remote villages, transportation costs can represent a real obstacle. Given the reality that sometimes a community will pay for the male authorities’ travel costs but not their female counterparts, without the women’s cooperatives it would often be impossible for women to travel to regional meetings, workshops, or assemblies. A woman might step down from her post if the community does not pay her transportation costs and she can’t afford it herself, but this happens less frequently in villages with women’s cooperatives.

Women’s cooperatives also invest resources into new projects. For example, as the village ofMorelia continued to grow, many of the younger families left to form a new community. The collective vegetable garden and bakery in Morelia each donated several hundred pesos so the women ofthis nearby village could form their own cooperative.

Although indigenous communities have a tradition of working collectively, women have historically been limited to working in the home. For many women, therefore, working in a cooperative is where they first began to participate in public spaces. Although the original purpose of women’s cooperatives was to strengthen the local and regional economy, they are also a critical tool for organizing women within the Zapatista movement. “We don’t only do the work of the cooperative,” said a group of Zapatista women from Olga Isabel. “We make agreements and we organize ourselves more. We also talk about the organization: we share information, we talk about politics, and little by little, women start to participate more.”32

A woman might also attend an educational workshop as a representative of her cooperative. Consuela is a coordinator of artisan cooperatives in Santo Domingo. “I go to meetings and trainings,” she said, “and I bring the information back to my municipality. I come back here and I have a meeting with all the local representatives to share what I learned. If it was a training workshop—sometimes they teach us sewing, for example, how to make a skirt—when I come back, I invite all the other women to teach them things they don’t know.”33 This work, of course, is not without its difficulties. “Sometimes they show up and sometimes they don’t,” Consuela added.

The physical act of working together is meaningful as well. Women go to their vegetable garden together, carrying buckets of water to and from the nearest river. Walking between the rows of vegetables, they splash water from their buckets onto the young green shoots. In the cooperative bakeries, women collect firewood to heat up the brick oven and then gather around long wooden tables to pound out the dough. They divide the dough into dozens of small yellow balls and then slide battered metal trays into the oven to bake the bread. The women who run the cooperative stores huddle together over notebooks full of handwritten lists, tallying the quantities of merchandise purchased by the store and community members who owe money. Women artisans gather to weave or embroider together, surrounded by colorful piles of yarn and cloth. Although their work is carried out individually, they compare ideas, view each other’s handiwork, and share each other’s company. “When we get together, we also talk among ourselves,” said the women from Olga Isabel. “When someone is sad or has a problem, we talk about it in the cooperative and try to resolve the problem. We do our best to support each other, because we don’t want anyone to be sad or to hold back ifthey have a problem.”34

When Zapatista women speak about their cooperatives, they often express pride about learning to do work that women have not traditionally done. Women from a village in Olga Isabel were proud of having planted a collective cornfield, for example, because planting corn is often considered men’s work. Women from another village nearby were pleased to have built the oven for their bread-making cooperative, out of mud and rocks. In the Garrucha region, women are quick to point to the women administrators who keep track of thousands of pesos ofthe store’s inventory.

Women’s cooperatives have also been effective in countering resistance from men. “Before, the men would yell at us, ‘You didn’t make the food! You didn’t wash the clothes!’” recalled Ernestina. “Or ifwe left the house, ‘You don’t have any rights. What were you doing out there? What kind of trouble were you looking for?’ That’s what it was like before, but not anymore. That’s why the women’s cooperatives are so important.”35 With Zapatista authorities calling on women to organize cooperatives, it has become more difficult for men to forbid their wives to take part in an activity that will benefit the community as well as the Zapatista movement. “There are still some men who criticize the women,” said the women from Morelia. “They say we don’t have the right to speak up. But it’s only a few men who still say those things. Now we have rights and the men respect us. When needs arise in the community, we can take money from our collective fund and the whole community sees that women are making a valuable contribution. The men think it’s good that we have a vegetable garden and other cooperatives.”36

Most of the villages in Olga Isabel joined the EZLN after 1994, much later than in the area around Morelia. Perhaps because of this, women in Olga Isabel found it easier to insist on their right to organize a cooperative in the first place. “The men have a cooperative store and they agreed to help us,” said a group ofwomen from Olga Isabel. “With money from the store, they bought seeds so we could start a vegetable garden. In this community, the men support us and help us. That’s why they thought about how to help us start our cooperative. They also helped us prepare the earth for planting.”37

Zapatista women from a village called Siete de Enero illustrated many of these themes when they shared the history of their women’s cooperatives during a regional women’s gathering in Morelia.

We began by organizing a vegetable garden. We chose our coordinators and then we had to get seeds. It was difficult because we weren’t used to doing this kind of work, but that’s why we feel strong now. We felt good when we were able to do it. At the beginning, people gossiped about us and criticized us. The priistas taunted us. The men didn’t recognize our rights as women. They said, “You aren’t men. Women should be making tortillas.” They made fun of us for doing this work, for going to meetings. We put up with it all, and since then we’ve made progress. Now things are much better. We began to organize, to have women’s assemblies, and to work in cooperatives.

We first decided to work in cooperatives because we saw the need. We wanted to help the autonomous commissions and the [health and education] promoters pay their bus fare. This way we have a little bit of money to support them in their work. That’s what our organization wants—for us to be working collectively, and this way we don’t have to scrape together the money.

We began the vegetable garden in 1996. We had a meeting and the women made an agreement to build the beds for the vegetable garden. Once we had made the beds, we bought the seeds. We each contributed one peso to get started. When the vegetables we planted grew, we harvested them. When we harvest radishes, we count how many women there are. Each woman gets a bunch of radishes but we each pay one peso so we can buy more seeds and plant more vegetables. That’s what we do with every harvest: each woman buys a bunch of radishes or lettuce.

We also have a store, which is another women’s cooperative. We began the store during the inauguration ofthe Aguascalientes in 1996. We organized ourselves to sell atole [corn-based porridge]. We borrowed six hundred pesos to buy meat and we sold tamales and coffee. We made a profit of 395 pesos and with that money we opened the store. The women do everything. There is a woman storekeeper and a coordinator who does the accounting.

Women have also benefited because now the men understand that women have rights, and they give us time to leave the house. Sometimes women take all their children to the meeting with them and the house is left closed. Sometimes the men help out when we leave our villages and go to a regional gathering. They stay home to take care of the smaller children and the animals.

When one of us goes to a meeting, we bring whatever we have learned back to our community and everyone benefits from that knowledge, those ideas. Those of us who are coor-dinators, we are not doing this work for our own personal benefit. We learn what we can, and we have to let go of our fear so that we can support our people.38

While women’s cooperatives are a key building block at the local level, women’s encuentros (gatherings) strengthen women’s organizing at the regional level. Dozens, sometimes hundreds of women representing different villages come together to share experiences and to learn from each other, to make decisions, and to coordinate regional projects. Like the women’s cooperatives, women’s gatherings are both a cause and an effect of women being well organized and are therefore more common in regions with stronger women’s participation. Some gatherings are specifically for representatives of the women’s cooperatives and emphasize skills or information relevant for them. At one such gathering, for example, Ernestina showed the other women how to make organic fertilizer for their collective vegetable gardens. Other women’s gatherings are broader and include a variety of topics and activities.

In 2001 and 2002, women leaders from the Morelia region organized a series of zone-wide women’s gatherings, which brought together women from several different autonomous municipalities. “The themes [for these gatherings] came from the women themselves,” explained Comandanta Micaela. “For example, the idea to give different workshops: there was a series of talks based on our own experiences and we analyzed our own lives. We spent a lot of time listening to women sharing their experiences of working with the church or with the community, or their experiences in their homes and with their families. It was a space to talk about many things.”39

Ernestina teaches other women how to make compost at a women’s gathering in Morelia. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Amelia, a Zapatista woman from Miguel Hidalgo who has served on several different autonomous commissions, described how attending these gatherings impacted her: “I like going to the zone-wide women’s gatherings very much,” she said. “I’ve had the opportunity to spend time with compañeras who live in other places, to hear about their experiences and learn from them.”40

The gatherings often include elements of culture and recreation. The day begins with the women singing the Zapatista anthem, and during a break in the middle of the afternoon they play basketball together. Amelia continued:

One of the biggest changes has been in sports, because we didn’t used to play sports at all. But once we began attending these gatherings, we saw that there were other women who played sports and we told ourselves we could do it too. Here in our autonomous municipality, we have gatherings with the men. It’s not a women’s gathering, it’s for everyone. We form teams and play basketball—the women, the children, the men, everyone. We participate equally, men and women. Before it wasn’t like that. The women were afraid. We felt that we didn’t know how to do anything. But now we know how to play, and we don’t feel shy about playing sports.

A cultural program often concludes the day’s activities. “The women who have more experience,” said Comandanta Micaela, “we help the young women write songs or poems or come up with skits to perform for the rest of the community so they can express themselves and explain to the community what they think and what is important to them.”41 Some of the songs are well-established classics about women’s liberation, like “Hoy Las Mujeres” (Women Today), sung to the tune of the Mexican revolutionary ballad “La Cucaracha,” or “Adelante Mujeres de la Tierra” (Onward, Women of the World). Other songs have been written by the Zapatistas, like the ballads about Guadalupe Méndez López and Olga Isabel.

Carlota, a women’s coordinator from Olga Isabel, described the women’s gatherings in her autonomous municipality.

Women in the village of Diez de Abril compete in a basketball tournament. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)

We have a women’s gathering once a month. Of the forty villages, the coordinators from about ten communities show up. So it’s only about twenty women, but there we are. We want more women to participate and we continue to invite them. At the meetings of the local representatives, we ask them to invite the women again. We want more women to come to the gatherings because we need to be united, and because it’s good for them to come and hear a little bit about politics or to learn about their rights as women.

The gatherings last for two days. The first day we have a training, for example about children’s health—why children get sick and how we can take care of them. Whatever we learn in the gatherings, we take that information back to our communities. The second day we work together in our cooperatives, sewing blouses or making bags or necklaces.

All the women help organize the gathering. I invite the women to participate and I teach them what I know, but we make all the decisions together. I just coordinate—I don’t tell them what to do. We do it this way so that all the coordinators will be able to take what they have learned back to their communities.

I always feel happy at the beginning of a women’s gathering because I know I will learn a lot. When the date of the next gathering approaches, I want it to hurry up and get there, because we know that someone will be coming to teach us something, and I like to learn new things.42

Zapatistas often talk about women leaders breaking down barriers for other women as abriendo camino—”opening the path” or “clearing the way” for those who will come after. “We like seeing women who participate,” said the Zapatista women who coordinate the cooperative store in La Garrucha. “We think the women who participate actively have good ideas, more experience. They are not ashamed or nervous to speak up. When one woman participates, other women feel encouraged to participate as well.”43

Sometimes the impact ofhaving a woman in a position of leadership can be seen almost immediately. In the late 1990s Isabel, the military leader who joined the EZLN when she was fourteen, was promoted within the military ranks and was moved to a different region. As the news in this region traveled that there had been a change in command and the new military leader was a woman, the shift was subtle but dramatic. Almost overnight it seemed as if women stood with their backs a little straighter, their body language conveying their pride and excitement. For many women, the simple fact ofhaving a woman in a position of military leadership made the impossible seem possible. There were also concrete changes that could be accomplished under a woman’s leadership. As Isabel described it:

I began by working with a group of women comandantas, regional coordinators, and other women authorities in that region and we grew stronger. We began to develop a work plan with more women in that region—a bigger, stronger group of women, a whole organization of women. With time, women felt more freedom and also more commitment. I wanted women’s struggle to be truly understood, so we analyzed it more.

But it wasn’t just women. We also included the male authorities. We began to organize gatherings with men as well, so they would, little by little, deepen their understanding ofwomen’s rights and the need to unite our forces to construct autonomy and what we call autonomous municipalities.

Couples would get up and give their testimony about how the woman had been able to move forward with her work, whether as a Zapatista authority or as a catechist. This testimony allowed people to see that there are men who have made sure their wives were at their sides and have always tried to move forward together. And then other men would realize, “What I’ve been doing is wrong, it’s no good.” This idea took root that it should not just be men who have the opportunity to go to assemblies and participate in the decision making. If a man is there, then his wife should be there too, so they can learn together. They also realized—through their own analysis, their own talks, their own testimony—that we cannot make a revolution only with men, that women’s participation is necessary too. It’s the organization that demonstrated this in practice, because there are women combatants and women who have authority within the military ranks and in the political structure as well. So anyway, we analyzed all this and realized that this is the best way forward: to work together and to overcome obstacles together.

With these gatherings, many of the compañeros did begin to understand and now they are putting it into practice. For example, they accompany their wives; they give them the freedom to go to meetings, to go to a gathering, to fulfill an obligation to their community, their municipality, the zone or the region.

We also need women to understand, to be in a more advanced stage and to have more freedom to do difficult tasks, because they will have to take on the responsibilities of being health, education, and human rights promoters—in other words, to occupy a series of spaces within the autonomous government.44

Isabel saw that the Zapatista communities had reached a kind of plateau, of women’s rights being publicly acknowledged but deeper changes being difficult to implement, and she employed a number of strategies to push past that impasse. When couples were invited to give their testimony at gatherings, for example, she would encourage men to become more active allies, and to provide examples of putting a rhetorical commitment to women’s rights into practice in their own families. Isabel initiated other changes that breathed new life into women’s organizing, including new regional women’s cooperatives and stricter enforcement of the Zapatista ban on alcohol. Less tangible but just as important was the generalized sense among women that there was someone in leadership who would defend and support them when necessary.

Isabel explained that being in this position of power was not without its difficulties and contradictions.

I think it’s very intense to have a woman in military or political leadership. For women, it’s a good thing. And for men who want to see changes, who want to change themselves and who want all human beings to have equality and rights, it’s a step forward. And a woman like that, with that authority, well, she can talk to more women and broaden their work.

But for men who don’t want to change, who want to continue with the way of life they’re used to within the capitalist system, that woman is dangerous! That woman might make his wife discover or understand the truth. And then there will be a series of problems for him. There are men who don’t want to see a woman as a military commander or a comandante or a leader.

I once asked one of the male comandantes who worked with Isabel what he thought about having a woman military leader. His wife is a comandante as well—it’s not uncommon for both people in a couple to hold positions of authority. I worked closely with both of them and I knew this man was supportive of his wife and accepting of women in positions of political leadership, but there is something very particular about having a woman in military leadership. Although there have been some powerful women in the highest military ranks of the EZLN, they are few in number. And the military structure is much more hierarchical than the political one, meaning that men have to take direct orders from a woman.

He responded candidly that the idea of having a woman military leader had been difficult for many men, himself included. At first, they flatly refused to accept a woman in command. But they were quickly told by the EZLN’s military leadership that they had no say over who was promoted within the ranks of the military, and that if they were not willing to work with a woman military leader, they were welcome to leave the organization. Once he began to work with her, he said, he learned a great deal, not only about women’s rights and women’s capacity to be effective leaders, but about political strategy and analysis. He acknowledged his own process of coming to accept that there is nothing wrong with a man being under the leadership of a woman, and he pointed out that if he had remained closed-minded he would have missed the opportunity to learn new things from her.

Isabel was in a unique and powerful position, but her efforts would not have come to much without women rushing to fill the spaces that had been created. Once they were given the opportunity, women participated in gatherings, took part in discussions, accepted the challenge of taking on new roles and responsibilities, and demanded ever more vocally that men respect their rights.

For two decades, Comandanta Ramona was an integral part of the Zapatista movement and one of the most highly respected members of the CCRI. Together with Comandanta Susana, she helped gather women’s opinions to shape the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Esmeralda, who knew Ramona well, described her role. “Since the 1980s, she and Susana were the first women leaders in the highlands,” she said. “In the early days, Susana and Ramona did much of the work throughout the whole highlands region, side by side with the first compañeros, and also the work with women. She was one of the first compañeras, and she gave a great deal to the organiza-tion. Much later, she told me it made her sad to see people selling her photograph because, she said, ‘I’m not fighting so they can sell my photo.’”45

As an ambassador of the EZLN to the outside world, Ramona became a powerful symbol of the Zapatista movement during the peace negotiations with the government and again in 1996, when she traveled to Mexico City for medical treatment and became the first Zapatista to make a public appearance outside of Chiapas. Just as peace negotiations with the government were breaking down, the Congreso Nacional Indígena (National Indigenous Congress, CNI) invited the EZLN to its first national congress, to be held in Mexico City in October 1996. After heightened tensions over whether or not a Zapatista delegation would be permitted to travel to Mexico City, Subcomandante Marcos announced that the EZLN would send Comandanta Ramona as its representative. “Ramona is dying,” Marcos told reporters during a press conference. “It is her last wish to talk to other Indians and tell them what the EZLN is all about.”46 Marcos’s announcement silenced the government’s objections, since she was a political leader, not a military one, and already gravely ill. On October 10, the entire community of La Realidad, together with dozens of armed Zapatista insurgents on horseback, gave Ramona an emotional send-off. Her trip to Mexico City demonstrated that the Zapatistas could break out of the military encirclement surrounding the EZLN in Chiapas, and, symbolically at least, take over Mexico City.

Large crowds gathered to greet her in San Cristóbal and at the airport in Mexico City. The people waiting for her outside the National Indigenous Congress enthusiastically cheered “¡Ramona salió y Zedillo se chingó!” (Ramona got out and Zedillo got screwed!), poking fun at Ernesto Zedillo, the president of Mexico at the time. Once inside the auditorium, elders from a number of other indigenous groups helped her onto the stage, where she was almost drowned in flowers. The gathering solidified support for the San Andrés Accords and helped unify the six hundred representatives of thirty indigenous groups who participated in the event. The CNI, one of many organizations formed in the political opening created by the Zapatista uprising, became an important actor in the national struggle for indigenous rights and the EZLN’s primary point ofcontact with other indigenous peoples in Mexico.

On October 12, celebrated as a day ofindigenous resistance throughout the Americas, Ramona addressed tens of thousands of supporters who had marched to the zócalo to demand indigenous rights. “We want a Mexico that takes us into consideration as human beings, that respects us and recognizes our dignity,” she said. “That’s why we want to unite our small Zapatista voice with the large voice ofeveryone who is fighting for a new Mexico. We came all the way here to shout, together with all ofyou, ‘Never again a Mexico without us!’ . . . I am Comandanta Ramona of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. I am only the first of many Zapatistas to pass through Mexico City and all the places of Mexico. We hope you will all join us in this path.”47 Nunca más un México sin nosotros (never again a Mexico without us) was the banner of the CNI’s first national congress and has become the slogan most associated with the Zapatistas’ struggle for indigenous rights in Mexico.

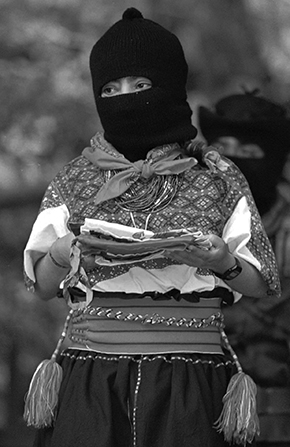

Comandanta Ramona in La Realidad, preparing to leave for Mexico City, October 1996. (Photograph by AP Photo/Scott Sady.)

After fighting kidney disease for ten years, Ramona died on January 6, 2006, in an ambulance on the way from her village to San Cristóbal de las Casas. Subcomandante Marcos, who was traveling around Mexico at the time, responded to the devastating news with these words: “The world has lost one of those women who gives birth to new worlds. Mexico has lost one of those fighters that it most needs. For us, it is like a piece of our heart has been torn out.”48 Esmeralda remembered Ramona this way:

She was very noble. She was quiet, but very perceptive. One time I saw her when she was leaving for Mexico City because she was sick. I was in a very difficult situation with my partner and she picked up on that when I saw her here [in San Cristóbal]. And she said to me, “Why do you seem so sad?”

I talked to her about it and she tried to cheer me up. She was one of those people who could read you, tell how you are, and not everyone can do that. And she was like that with everyone, always giving of her time, her work, her words.

Her illness took a lot out of her, but when she recovered a little she went back and reintegrated into her community as soon as she could. And she was always the same: gentle, unassuming, encouraging other people. But her health had worsened a great deal—she was very, very sick.

It was very difficult for Susana because the two ofthem grew together within the EZLN. They were from different villages but they worked closely together. I went to San Andrés when they buried Ramona and I saw Susana there. She hugged me tightly and started to cry. “But yesterday she was still eating,” she said. “She was still talking.” Susana felt her death very deeply.49

Women leaving the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering with a shrine to Ramona in the back of their truck. (Photograph by Marina Sitrin.)

Despite Ramona’s wishes, her image can be found on postcards and T-shirts, as handmade dolls sold on the streets of San Cristóbal, and painted on murals in Zapatista communities. Her compañeras and compañeros mourn her death but are committed to keeping her memory alive. The Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering held in La Garrucha in 2007 was named after her, and during that event her legacy was evoked again and again. Women from the highlands talked about her with the love and familiarity that comes from having known her personally. Women from other Zapatista regions spoke about her with reverence and admiration, and gratitude for the work she had done to make it possible for them to be standing there. Many non-Zapatista women spoke of Ramona as an important role model as well. “As we learn to do new tasks,” said Everilda, an alternate member ofthe CCRI, during the event, “we take them on with our entire being and consciousness, and the only reward or compensation we receive will be the satisfaction of having fulfilled our responsibility. This is what our Comandanta Ramona taught us to do. She carried on with the struggle until the last day ofher life.”50

Zapatista women at the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)