Any visitor to San Cristóbal de las Casas who sits in the picturesque zócalo in the center of town will inevitably be surrounded by young indigenous children with outstretched hands. “Un peso ... ?”they greet you plaintively, asking for a Mexican coin. Indigenous women will approach you as well—striking in their colorful traditional clothing, artisan crafts piled high over one arm, their voices with an edge of desperation as they ask you to buy a bracelet, an embroidered piece of cloth, a Zapatista doll. If your eyes linger on a particular item, they will push it toward you persistently, asking how much you are willing to pay. This relationship is so fraught with structural inequality that it can leave a bitter taste in your mouth whether you purchase something from the women or not, whether you give the children money and they run away gleefully, or whether you turn away.

What a contrast, then, to drive several hours down the winding mountain highways of Chiapas and another few hours over bumpy, dusty dirt roads, and find yourself in Zapatista territory—where indigenous communities have taken their destiny into their own hands, where villages find solutions to their economic problems by working collectively, where community members walk proudly, where Zapatista authorities tell nongovernmental organizations which community projects will be needed, and where Mayan culture and traditions are a source ofhonor. On a political level, autonomy is about self-determination. On an emotional level, it is about dignity.

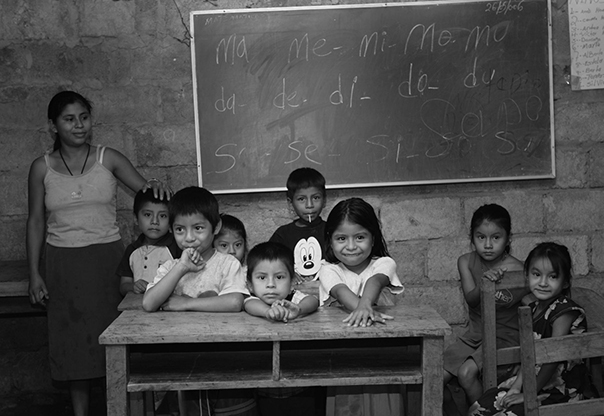

When I arrived in Chiapas in 1997, the project of Zapatista autonomy—the political, economic, and social infrastructure that allows the Zapatista movement to function independently of the Mexican government—was still young. The system of Zapatista authorities already in place (local representatives, regional coordinators, and the CCRI) was the EZLN’s political structure that had existed since before 1994. As autonomy took shape, a new leadership and decision-making structure emerged that began to function as a government, parallel to the Mexican state. Autonomous councils were formed in each autonomous municipality. There were already autonomous schools and health clinics in some Zapatista villages, but a health care and education system was established to support and grow this infrastructure. Autonomous commissions were created to oversee each area ofwork: health, education, land and territory, honor and justice, and culture, among others. Many key areas of Zapatista autonomy—health and education projects, economic cooperatives, and the structure of assemblies—drew upon elements of indigenous culture and also built on traditions and practices developed in previous decades by the diocese and campesino organizations that preceded the EZLN.

Today, there are two parallel sets of civilian Zapatista authorities: the EZLN’s original political leadership and the autonomous government that was formed later—made up of five Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Good Government Councils), an autonomous council in each of about thirty autonomous municipalities, and several autonomous commissions. The EZLN’s military hierarchy is separate from these two sets of civilian authorities but has also played a role in the organization’s political direction, especially in the earlier years of the movement. The function of all three sets of authorities has become clearer and more distinct over time, as the EZLN’s military hierarchy gradually began to limit its involvement in civilian affairs, and as the autonomous government gained the experience necessary to take on more responsibility. Their roles still overlap to some degree, but the political authorities make up the leadership structure of a political-military organization, whereas the autonomous authorities represent a civilian government, emerging directly out of the indigenous communities. The autonomous government is much more accessible, for example. The autonomous councils have offices that are open to all visitors, whereas the Zapatista political authorities are still shrouded in an air of secrecy. Members of the autonomous councils are chosen for a set amount oftime and then a new group is elected, whereas the political leaders remain in their positions indefinitely.

When my colleague and I began our project with women’s coop-eratives, we communicated primarily with the regional women’s coordinators, who were part of the preexisting Zapatista leadership structure. In 1998, we were asked to support the Women’s Commission of the autonomous municipality Diecisiete de Noviembre. The Women’s Commission’s written guidelines stated that women have the right to receive additional training to ensure their equal participation in the movement, and we were to provide this training. In spite of the guidelines, however, no one seemed exactly sure what this commission was supposed to do. We facilitated a series of meetings between the members ofthe Women’s Commission and the long-standing regional women’s coordinators to develop a work plan for the newly formed commission. Those meetings included many serious moments, discussing the vision for the work and the urgency of organizing with women, drawing maps and making calendars for the communities they would visit; and some entirely silly moments as well, like when all the women collapsed into giggles one afternoon after one of them suggested that inspiration might strike while we were in the latrines because ofall the abono orgánico (natural fertilizer) in there.

The work plan we developed looked remarkably similar to what the regional women’s coordinators were already doing—visiting each community to support women’s organizing, encouraging the formation and growth of women’s cooperatives, and holding women’s regional gatherings. The distinction between the regional women’s coordinators and the Women’s Commission was not entirely clear to us. As it turned out, we were not alone in this confusion. The new autonomous councils were going through the same process with the preexisting political authorities. We were all stumbling, somewhat blindly in those days, toward something that would appear much clearer with hindsight—the transition from the EZLN’s political-military structure toward its structure of autonomous government.

In August 2003, the EZLN declared the birth of the Caracoles. Previously called Aguascalientes, the Caracoles are the five centers of Zapatista territory: Morelia, La Garrucha, La Realidad, Oventic, and Roberto Barrios. Caracol means “snail shell” in Spanish, connoting the conch shell the Mayans traditionally used to call a meeting. The spiral figure ofthe Caracol also represents dialogue, a central concept for the Zapatista project. With the birth of the Caracoles came the Juntas de Buen Gobierno. The inauguration of the Caracoles was like a coming-out party for the Zapatista project ofindigenous autonomy. The EZLN had first declared the existence of more than thirty autonomous municipalities in December 1994. For several years, however, the autonomous municipalities existed more or less in name only. During the late 1990s, as the Zapatistas were figuring out what their version of indigenous autonomy would look like, they were cautious not to talk about autonomy publicly.

If the Mexican government had implemented the San Andrés Peace Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture, the Zapatistas, along with other indigenous groups throughout Mexico, would be able to govern themselves according to their customs and traditions and control their own natural resources. But in 2001, the Mexican government passed the Indigenous Law, a legislative version of the San Andrés Accords so watered-down that the EZLN rejected it out ofhand. The Zapatistas effectively stopped calling for the implementation of the San Andrés Accords and abandoned any expectation of government sanction for indigenous autonomy. A Zapatista slogan, “You don’t need to ask permission to be free,” encapsulates the EZLN’s decision to implement indigenous autonomy on its own terms. In this small corner of the world, the Zapatistas are experimenting with their own government, alternative education and health care infrastructure, along with an economic system based on cooperation, solidarity, and relationships of equality.

The [Zapatista] authorities don’t make decisions on their own, they have to lead by obeying. They have to listen to everyone and take into consideration what the people want. The government does whatever it wants to. Our indigenous authorities lead, but they lead by obeying.

—OFELIA, a Zapatista woman from La Garrucha1

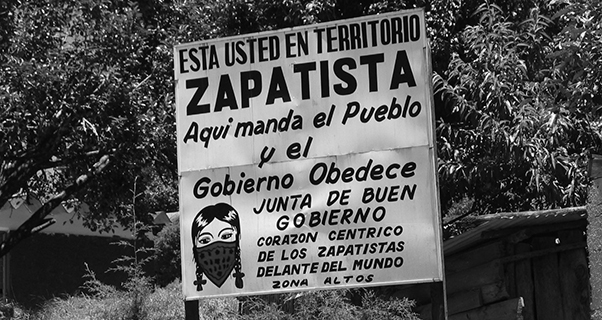

The autonomous government in Zapatista territory is parallel to but separate from the Mexican state, and founded on the principle of mandar obedeciendo (to lead by obeying). There is a sign at the entrance of each Caracol that announces: “Está usted en territorio rebelde zapatista. Aquí manda el pueblo y el gobierno obedece” (You are in rebel Zapatista territory. Here the people lead and the government obeys). “As autonomous authorities we can’t impose our ideas,” said Citlali, a member of the Good Government Council from the Garrucha region. “We can only present our proposals. Then the people have to approve our proposals, because the people are the highest authority.”2

A sign in Zapatista territory reads: “You are in Zapatista territory. Here the people lead and the government obeys.” (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)

The Zapatista autonomous government consciously draws upon many elements of traditional indigenous structures and seeks to implement a system of direct democracy, where all voices are heard in decision-making and everyone can and should participate in community affairs. Some elements of governance that embody this principle and predate the Zapatistas include the community assembly, the system of cargos (positions of leadership or authority), and the permanent consulta (a process of consultation with the people through community assemblies or other mechanisms). Community assemblies have historically been an important institution in Mayan villages but were not inherently democratic. Assemblies became considerably more deliberative and participatory under the influence ofthe Catholic diocese and Maoist organizations in the 1970s. In Zapatista territory, decisions are made by an informal process of consensus and no decision can be reached until everyone who wants to speak has spoken. All major decisions are made in an assembly, and the autonomous government is to implement those decisions. The regional assembly chooses members of the autonomous government, and assemblies can remove someone from their position ofauthority at any time.

Cargos are the structure of traditional indigenous authorities. To hold a cargo, or a position of authority, is a way to offer service to one’s community. The Spanish word cargo also means a weight or a burden, and the verb cargar means “to carry,” so to have a cargo is like shouldering a burden or carrying your share of the weight. While it is a position of power, it implies a financial sacrifice rather than a path to wealth. Historically, anyone holding a cargo was expected to sponsor religious festivals which depleted any wealth he had managed to accumulate. By accepting a cargo, one gained prestige but became impoverished. On the other hand, this system tends to concentrate power in the hands of wealthier community members since they are most able to absorb their high costs.

The autonomous government reflects several aspects of this system. “We don’t go out and campaign like the politicians of the bad government,” said Citlali. “The people choose the person who they think will do the best job. We are very clear that we, as authorities, are providing a service to our communities and we are not thinking about receiving any kind of salary.”3 Those elected do not nominate themselves or ask to be chosen, and the Zapatista authorities are not financially compensated in any way. As was the case for traditional Mayan authorities, being chosen as a member of the autonomous government is seen as a hardship as well as an honor. The authorities gain prestige and are respected by their community members, but they are also closely scrutinized by their peers and are, at times, subject to heavy criticism.

Both the difficulties and the benefits are amplified for women. Since women are still the primary child-care providers, it is often harder for them to leave home for days at a time. The criticism women face can also be particularly harsh. “There are times when I hear the rumors about me and it makes me cry,” said one Zapatista woman leader, “and then I pull myself together. I know what they’re saying isn’t true, that’s why I’m still here.”4 On the other hand, what they learn from the experience can be more transformative for women, who have had less access to positions of leadership in the past. “In my work with the organization, I am always learning,” commented another Zapatista woman leader. “With the other authorities, with the other women, we learn from each other. One person gives me an idea here; another person gives me an idea there. My heart grows and I want to keep doing more.”5

A consulta is something like a popular referendum, but is carried out by discussion rather than voting, allowing people to participate directly in decision-making in a regular and ongoing fashion. The Zapatistas conduct a consulta when an important decision needs to be discussed not only in the regional assembly but also in every community. The EZLN’s decision to go to war with the Mexican government is the most frequently cited example, but a number of other proposals or decisions made by the highest echelons of Zapatista leadership have been taken to the support-base communities and discussed in each village.

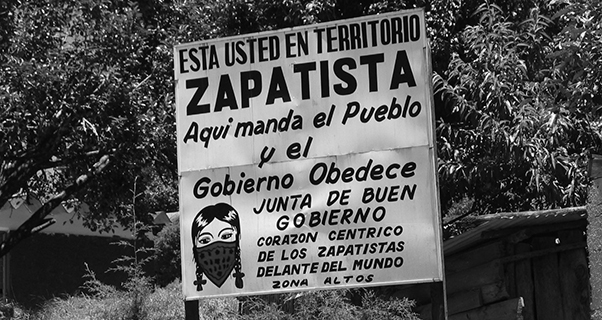

“Our communities have elected us to organize,” said Eliza, a member of the Good Government Council from the Morelia region, “to govern and to be governed; [we are] seeking a way of doing politics, a government which promotes the collective and communal interests of the people, a government which leads by obeying. The council is also the bridge between the Zapatistas and the peoples of the world.”6 Each of the five Caracoles has a Good Government Council, made up of rotating members of the municipal councils of the autonomous municipalities in that region. Each rotating group stays in the Caracol for a one- or two-week shift, during which time it constitutes the Good Government Council. The length of time depends upon the particular Caracol. The Zapatistas say that having so many members on the council and the frequent rotations hold them accountable and act as a measure against possible corruption. As the “bridge between the Zapatistas and the peoples ofthe world,” these bodies also receive all visitors to Zapatista territory. After two decades as a clandestine organization, the EZLN opened offices for the Good Government Council in each Caracol where anyone can go and meet with them. Citlali described her work on the council.

We have the responsibility to promote the different areas of our work, such as education, health, and production. We resolve problems. We register the cooperatives in each community. We administer the funding or donations that we receive from our brothers and sisters in solidarity. The job of the Good Government Council is to even out the economic resources so that each region or autonomous municipality receives the same amount.

It’s hard because we still don’t have the knowledge and experience to do the work, and we don’t have a manual to tell us what to do. It’s just us, creating the path of autonomy as we go. We are doing our best, even those of us who don’t know how to read and write. We have said since the beginning that we will learn, little by little, because the people themselves guide us and teach us.7

The Zapatistas draw on elements of traditional indigenous governance, but recognize the need to incorporate their own principles as well because, for example, there are traditional indigenous authorities throughout Mexico who are corrupt agents of the state. “We want to govern ourselves as indigenous people, but we want indigenous leaders who obey the people,” said Margarita, one of the women from Morelia who helped protect her community from Mexican soldiers.8 Furthermore, men have historically dominated traditional indigenous governments. Zapatista autonomous government combines indigenous customs, structures they inherited from other organizations and institutions, and the Zapatistas’ own beliefs and practices. The Zapatistas bring an anticapitalist analysis, a critique of corruption within the Mexican state, and a commitment to gender equality and the inclusion of women.

Kim Klein, the author’s mother, poses with the Junta de Bueno Gobierno in Oventic, 2009. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

The reality of women’s participation on the Good Government Councils, however, is mixed. It varies from Caracol to Caracol and even from one rotation to the next. Women’s participation has grown stronger since the councils were formed in 2003, but years later it was still common to walk into a meeting with them and find that most of the people seated in front ofyou were men, or that the women present would sit apart from the men and say little during the meeting.

Even in regions with stronger women’s participation, the women on the Good Government Council are often young and inexperienced. The older generation ofwomen leaders—women with years and sometimes decades of political experience in the Zapatista movement—were already part of the EZLN’s political structure as regional coordinators and comandantas when the councils were formed. So a younger generation of women began filling positions in the new autonomous government. For many of these women, being on the council was the first political position they had held. Meanwhile, there was a larger pool of men with some leadership experience who could fill these slots. This often created a disparity between men and women on the council.

In other regions, women had to stand up for their right to serve as members of the autonomous government. Citlali described this process in La Garrucha.

When the Good Government Councils began to function, that’s when we began to participate as women, since it was publicized that we all have the right to participate and that this was important to strengthen our autonomy. But it was difficult to explain to the men that we had the right to participate as authorities on the Good Government Council. They still have these bad ideas that come from the bad government. Sometimes they think we’re worthless or that we can’t do office work. We began to unite as women to defend our rights and demonstrate to the compañeros that we are able to do this work.

Citlali’s words echo other women’s descriptions of having fought for their right to participate in the movement years earlier.

Regardless of how they got there, many of the young women on the Good Government Councils are confident and full of pluck. Eliza belongs to this younger generation. She attended autonomous schools as a child, speaks Spanish fluently, knows how to read and write, and is much more comfortable using the donated computers in the council’s offices than her older male counterparts. Eliza began serving on the council at age seventeen, which is not uncommon, and completed a three-year cycle as a member of the autonomous government in rebel Zapatista territory by the age of twenty. She has received national and international visitors to the Caracoles, participated in decisions that impacted the entire region, and helped to resolve conflicts and disputes. She has spoken at assemblies and public events before hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people. Eliza is part of a generation ofyoung women leaders who are benefiting from this experience, and a manifestation of the many changes that have already taken place in Zapatista communities. One can only imagine what these women will be like, and how the society around them will have been transformed, by the time they are thirty, forty, fifty years old.

When those of us who grew up in the United States think of the physical characteristics of the judicial system, a stately white courthouse might come to mind, or a judge in long robes, holding a gavel and sitting high above us to pass judgment. In the Zapatista communities of southern Mexico, justice is carried out in humble, one-room buildings. A group of five or six elders, some men and some women, sits behind a long table hewn out of rough wooden planks. Wearing worn work clothes, they probably walked several hours to get there. They ask questions, listen carefully, and bow their heads together to consult with one another. When they speak, it is to ask the person before them to consider their responsibility to their community.

In each Caracol, the Good Government Council and the Honor and Justice Commission work together to resolve individual, family, community, and political disputes. The council has a wide range of responsibilities, whereas the Honor and Justice Commission, some-thing like the judicial branch of the autonomous government, is specifically dedicated to mediating disputes, facilitating agreements, and determining punishment when wrongdoing has been committed. The Honor and Justice Commission is generally made up ofindigenous elders, recognizing their traditional role in resolving disputes and their moral authority with other members ofthe community.

The racism and corruption deeply embedded in Mexico’s judicial system mean that there is little chance for a rural peasant from an indigenous village to receive fair treatment within that system. Indigenous peasants, regardless of their political affiliation, are well aware of this. “We never go to the government anymore when we have a problem,” said Guadalupe, a Zapatista woman from Miguel Hidalgo. “We used to go to the government offices in Comitán. If you have money, then you pay for a solution to your problem, but if you don’t have money, your problem is not resolved.”9

Ruth, a Tzeltal woman in her fifties, is a member of the Honor and Justice Commission in Olga Isabel. She furrowed her brow as she explained the Honor and Justice Commission’s role.

When we resolve problems, most of the time it’s not with compañeros, it’s with priístas. Many people come with their problems and we don’t earn anything. They don’t pay us anything, not even a penny. It’s not like the government in Yajalón, where you have to pay for justice. That’s why so many people come to us, even the priístas. Even if they don’t like our decision, they respect it, because they were the ones who came to us looking for a solution. The first time, they come on their own. After that, we set a date for them to come back a second or a third time. Once we have all reached an agreement, we write up a document stating what the agreement is.10

The autonomous justice system could loosely be characterized as transformative or restorative justice because it looks at problems and disputes in the context of the larger community or society, seeks to transform the attitudes or behavior of the person who committed wrongdoing, and focuses more on healing than imprisonment or punishment. When someone is considered to be at fault, the members of the Good Government Council or the Honor and Justice Commission offer words of advice to ensure that the person understands what he or she did wrong and encourage them not to do it again. In most cases, they facilitate an agreement to resolve some type of dispute. But there may be a punitive element as well. The council or the Honor and Justice Commission may determine who was at fault and impose disciplinary measures. Punishment usually involves making reparations to whoever was directly impacted by the wrongdoing, or making amends to the community as a whole in the form of community service. There are jails in Zapatista communities, but people are rarely detained for more than a day or two. The most common use of the jails is to lock someone up for being drunk, and they are usually in jail only until they are sober. Ruth continued:

We work every Friday and Saturday. We are in the Honor and Justice office all day to receive people who want to resolve their problems. At the beginning of each day, we pray first, because sometimes the problems are very difficult. People come here with their problems and sometimes we don’t know how we are going to resolve them. We have to try to understand which person is instigating the problem. Sometimes the people who come here looking for solutions to their problems get angry.

Couples come here who want to separate, or the man wants to go off with another woman. If a man wants to leave his wife, I ask him, “Why do you want to look for another woman if you’re already married?” Sometimes the man rejects his wife because all their children are girls. It’s very difficult work. Sometimes the man will say, “I don’t want to be with my wife anymore.” We tell him that it’s not right to leave his wife, because he has children. In one case like this, I asked the woman and she answered that she did not want to be left alone to care for the children. I told her if he leaves her, then he should be the one to go and should leave her the house and the land. The woman was asking for money. She said that if her husband left her, then he should pay her 5,000 pesos. They have five children. I told her, “Even 5,000 pesos will not be enough to raise your children.” It costs a lot of money to raise children. I counseled the woman and explained to her why her husband wanted to leave her. The Honor and Justice Commission’s decision was that if the husband was going to leave his wife, she was to keep the house and the land. They did not separate. The man decided that it was better to stay with his wife.

Although the autonomous justice system strives to treat men and women equally, women have legitimate reason to fear that this might not always be the case. “If there are no women on the Honor and Justice Commission or on the council, we can’t go to them with our problems or tell them our stories,” said a group ofZapatista women during a collective interview in Olga Isabel. “There are certain things we can’t tell the men, it’s too difficult. Some men still don’t take us seriously, or they ask us questions but only so they can talk badly about us afterward. Now there is space for women to be part of the autonomous government. It’s important for women to accept these roles and learn to do the work of the autonomous government.”11 Women like Ruth help ensure this kind of fair treatment. “On the Honor and Justice Commission, men and women work together and we speak with one collective voice,” she said, “but when a woman comes to our office, I usually speak with her alone. When it’s a family problem, the men speak to the man and we speak with the woman. There are four men and two women on the commission.”12

Male authorities have an important role to play as well. When a man has committed an act of violence against a woman, for example, male authorities will generally tell him that his behavior is unacceptable. This represents a significant shift in social norms, due in large part to the Zapatista movement. Pacheco, for example, served on the Honor and Justice Commission in his region of Santo Domingo for three years before becoming a member of the Good Government Council. He explained to me:

If there is a family problem, we try to reach an agreement. We tell them that they should not be looking for problems. Sometimes there are punishments for the compañeros who abuse their compañeras. Within zapatismo we have rules about this. Ifit is the third time, they are punished. Ifit is the first or second time, we only give them guidance and advice. We use words to try and make sure the man is on the right path.

We ask him to promise not to abuse his wife again. But if it is the third time, we cannot pardon it again. There is a punishment of working for the collective for thirty days.

But there are not many cases of that here. In this municipality it has never reached the point where we have had to punish someone. They might come once or twice but not three times. The men don’t abuse the women as much anymore. I think it’s because we prohibited alcohol and the men don’t drink anymore.13

The autonomous justice system is also prepared to respond to cases of sexual assault. “We know there are cases of rape,” said Ruth, “and we have guidelines about how it should be punished, but we have not had to resolve a case like that yet. It’s difficult when the woman doesn’t want to talk. We knew of one case of rape but we could not do anything because the woman didn’t want to denounce it.”14 Ruth raised the point that the autonomous justice system relies on people’s willingness to denounce a crime. For now at least, there is no mechanism to deal with an incident if the victim or survivor chooses not to come forward.

The gender analysis present in the autonomous justice system benefits non-Zapatista women from neighboring indigenous communities as well. “Ifthere are cases ofabuse against women, rape or other things,” said Eliza, “it is our duty to resolve this compañera or hermana’s problem, because in our struggle, it doesn’t matter if the woman is a Zapatista or not, we have to resolve her problem.”15 (Eliza referred to a woman who is not a Zapatista as hermana, which means “sister.”) Ruth stated that, in her municipality, the majority of cases involving violence against women are brought to them by non-Zapatistas.

Isabel also offered her assessment of the autonomous justice system and some of its limitations in responding to violence against women.

It really depends on who is in a position of authority in the community. If they take the Women’s Revolutionary Law seriously and make their judgment according to it, then yes, they will reach an agreement where everyone is all right. But there are authorities who do not obey the Women’s Revolutionary Law and who resolve problems according to their own views. It depends on the authorities’ capacity, because they do not all have equal experience in standing firm about this. So there are times that, yes, they come to good agreements. But there are also times when we see, once again, that the problem was not resolved or that the solution offered was not a just one.

But I also think we are lacking a women’s organization, which would give its point of view as a group of women: “We have here the Revolutionary Law and, as authorities, we want it to be taken into consideration in such and such a way . . .” That’s what we need. It’s true that space has opened up for women to become authorities, as community police officers, as ejido commissioners. But women still lack expe-rience in these areas, they have not developed their capacity yet. It’s as if men still have a stronger voice than women in resolving these types of problems, or it’s left up in the air and then all the women can do is complain about it afterward: It’s not right. It shouldn’t be like that. The authorities should have acted moreforcefully. It should have been resolved differently.

Are there still cases of rape or violence? Yes, they still exist. Some women are willing to accuse their attacker and some women are not. For the women who are not, the case is never resolved—it’s just left the way it is. But does violence persist? Yes. It’s there. We are better organized now and there are more ways to ensure that our laws are implemented, but we still have not reached the point where they are really implemented the way they should be. There are several spaces but it’s still not very . . . it’s still not perfect. It’s in the process of being perfected. Things still need to move forward within these spaces.16

Carlota, the regional coordinator who helps organize the women’s gatherings in Olga Isabel, began experiencing abuse from her husband. Instead of remaining silent, she brought her case to the Honor and Justice Commission in search of a solution.

I know I have rights; that’s why I accepted my cargo. But the men criticize me. Even some women criticize me. My husband tried to deny me my rights but women have to be strong and stand up for ourselves. When I left the house, my husband would tell me not to go out. But I would gather my courage and leave. I knew I needed to make an effort to do something good, to learn something. Even if your husband is supportive, you can still have problems. Other people criticize you. At one point, we began to have more serious problems. There were rumors and criticisms and my husband got very angry. We had problems for a while and I stopped participating. I stopped going out until we resolved this problem.17

The rumor circulating about Carlota was that she was involved with another man. Carlota repeating several times that she and her husband were having problems was her way of saying that, having believed these rumors, he was being physically violent. Ruth, who was on the Honor and Justice Commission when Carlota brought her case, recalled:

It can be difficult to resolve these problems. It turned out that the young man who started the rumors had been saying that the two of them were in love, but it was just gossip. It was only him that was in love with her. It was a serious problem. The young man came before the Honor and Justice Commission and insisted that he really did love her. He kept saying that he loved her, even though she had a husband and her husband was right there. The things he said about her were not true. We punished the young man. He was in jail for one day and one night and we made him carry cinder blocks for a day, barefoot and with no food.

Carlota was pleased with the outcome and proud ofherself for having taken her case to the autonomous authorities.

Once we found out who was starting the rumors, my husband understood, it was all cleared up, and now we do not have problems anymore. We resolved the problem with the Honor and Justice Commission. That’s why my husband accompanies me now. We agreed that he would travel with me to see that nothing was going on and now I am actively participating again. Where we live is very isolated. If someone else can accompany me, I go with her. Ifnot, my husband comes with me. Now he respects me because he realized the things he heard were not true. I’m happy now because the problem was resolved and things are good between us.18

The Zapatistas have worked to build a “solidarity economy” in their territory—economic infrastructure where the well-being of society is more important than generating profit, and where solidarity is a strategy to improve the living conditions of the entire community. The economic cooperatives, run by both men and women, form the backbone of the autonomous economy. Long a mechanism for economic self-sufficiency in Zapatista communities, these cooperatives were later incorporated into a regional economy and began to play an increasingly significant role in the project of indigenous autonomy by generating funds for autonomous government, health care, and education.

Working collectively is a guiding principle of a solidarity economy and an example of how indigenous culture is incorporated throughout the Zapatista project of autonomy. “Our ancestors lived and worked collectively,” said Ofelia, the administrator of the women’s cooperative store in La Garrucha. “Whenever they organized some community project, they included everybody. But this way ofworking together, of living collectively, had been lost. People did their work individually, each person for himself. For example, when somebody got sick, there was no structure to help each other out. So we began to think about whether there was another way to do things. We began to see that many solutions are possible if people work together.”19

“When we organize to work in cooperatives, it is part of our resis-tance,” said Fernanda, a member of the Production Commission in Santo Domingo. “We have our own ideas about how to construct autonomy. We are figuring out how to do things for ourselves, and we are breaking away from control by the bad government.”20 A Production Commission oversees the autonomous economy in each municipality and each zone.

Most Zapatistas are subsistence farmers, and plant corn and beans to feed themselves and their families. But they also sell a portion of their crops to generate some income, and many families raise animals or plant cash crops in addition to their subsistence crops. Like other peasants, they are vulnerable to the fluctuations of the market, and rural poverty is structurally reinforced when, each year, they harvest their corn and are obliged to sell a portion of it to pay back debts and to acquire a little cash for basic necessities. Since everyone harvests corn at the same time, the price to sell corn is very low. Later in the year, when they run out of corn, they must buy it at a much higher price. Several autonomous municipalities have sought to address this cycle of poverty by setting up warehouses to store grain and creating bartering mechanisms so individuals or communities with a surplus can trade with others on a more equal footing. Grain can be stored and therefore bought and sold for a stable price throughout the year. In this way, regional economic structures have institutionalized the distribution of surplus. The Production Commission also works to strengthen agricultural production, recovering traditional knowledge as well as learning new methods of organic farming.

Amelia, who was twenty-eight and had four children when I interviewed her in 2006, is a member of the Production Commission in the Morelia zone. Amelia is a mestiza woman, which is unusual for the Zapatista support base. She speaks Spanish as a first language, went to school as a child, and knows how to read and write. All these things set her apart from many of her peers, and at first she was somewhat standoffish with the Tzeltal women in her region. She is still very matter-of-fact but came to develop a deeper sense of solidarity with her compañeras.

All the work is included in our plan, individual as well as collective work, and we are promoting all types ofproduction: corn, beans, vegetable gardens, raising cattle, everything that we can, and commercialization too. It’s all included in our work plan. We make sure that tasks we have agreed upon get done and we decide what gatherings need to be organized, or, for example, with the artisan cooperatives, what workshops we want, where, and how many workshops per year. All that is part of coordinating the work. It is more work, but I see how important it is, and I’m learning new things.21

Amelia had originally been part of the Women’s Commission in the Morelia region, whose primary task was to oversee women’s cooperatives. “After I had been working with the Women’s Commission for a while,” she explained, “we joined together with the men on the Production Commission. We combined the two areas, women and production, because we saw that it was basically the same work.” This decision was made, in part, to recognize the importance of women’s economic activity. Morelia’s Production Commission, however, is unique in this way. Many autonomous municipalities do not have a Women’s Commission, and many Production Commissions focus on economic activities typically done by men. Amelia talked about the decision to fold the Women’s Commission into the Production Commission.

In my opinion it’s important for men and women to work together, because we both help each other. Sometimes we have to write proposals and when we can’t do it, the compañeros help us. Before, when the women were on our own, well, sometimes it didn’t turn out so well because we don’t always have the capacity to explain certain things. Sometimes we don’t know how to respond to certain questions. We have seen that it’s easier working together with the men. The women can also make proposals regarding the men’s work.

There are advantages and disadvantages, because when we’re together, we can help each other. For the women, though, many of them have a hard time speaking up. They are more afraid to speak in front of the men. So that’s the difficulty I see. Sometimes, when there are questions just for the women, we meet separately and then the women participate more. Afterward, we rejoin the men. It’s an agreement we have on both sides.

If there’s a woman who doesn’t want to participate, I go to her and say, “Compañera, you should share your thoughts so you’ll stop being afraid to speak up,” or “What do you propose about the work we’re doing?” But I say this to her when we’re alone, so she can learn to speak up too. That’s how I encourage other women. I tell them that nothing bad will happen when they speak up, and whether it comes out well or not, the important thing is for them to participate so they can learn.

I’ve been leading the work here in my municipality because there are three of us who were chosen from this municipality, but the other two compañeras don’t participate. They have left me on my own. When I’m away from home, I feel like I’m abandoning my children, and also my housework and washing the clothes. That’s one ofwomen’s main tasks, washing the clothes, and sometimes when I’m away from home, the housework piles up.

Fernanda is on the Production Commission in the autonomous municipality Santo Domingo (which is part of the Morelia region). She is just as committed to her work but faces some of the obstacles that Amelia acknowledged.

I go to the meetings, but it’s more difficult for those of us who don’t know how to read and write. They give us a list of questions but I don’t know how to answer. They ask us what work we’re doing in each municipality, if we have vegetable gardens, collective cornfields, bread-making cooperatives, chicken-raising collectives. If I can’t find someone to help me, my municipality loses out because they develop a work plan according to the needs of each community. We write down what materials we use. For example, if we’re going to plant a vegetable garden, we need picks, shovels, and watering cans. If I don’t answer the questions, the needs of my municipality will not be included in the work plan. As a woman, I want to do the work, but it’s difficult because I don’t speak Spanish, I don’t know how to read and write in Spanish, and sometimes I don’t understand what people are saying.22

Since the Women’s Commission in Morelia was integrated into the Production Commission, strong leadership from women is built into this body in a way that is not the case for any other area of the autonomous government. This speaks to the importance ofwomen being fully integrated into all areas of the movement. On the other hand, women sacrificed having their own separate space, which has a different set of advantages. The evolution of Morelia’s Production Commission points to the importance ofboth, as well as the contradictions that can exist between these two aspects ofwomen’s leadership.

We are organizing on our own to help each other. That’s what autonomy means—that we’re doing it on our own. The government doesn’t provide us with any services anyway.

—Women health promoters from the autonomous municipality Lucio Cabañas23

Many indigenous villages in Zapatista territory are far from the nearest city and historically had limited access to doctors or health clinics. There were no schools on the large plantations where many indigenous communities lived and worked. In villages that did have schools, the Mexican government used them as a tool of assimilation. Women faced particular health problems, like high rates of maternal mortality, and even more restricted access to education.

The EZLN was not the first organization that sought to address the marginalization of Chiapas’s indigenous communities. The Diocese of San Cristóbal began training catechists as nursing assistants in the 1950s and a variety of organizations trained health promoters throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The FLN gained its initial access to communities by providing health services and its safe houses had an educational component as well. ARIC, one of the prominent campesino organizations, carried out literacy programs in the canyons.

Building on these experiences, the EZLN set out to create comprehensive and explicitly Zapatista health care and educational systems, drawing on indigenous culture and traditions but also with its own revolutionary perspective. Each village chose its own health and education promoters who, in the early stages, were mostly men. Increasing numbers of women became involved over time. The promoters are expected to serve and be accountable to their community. At the regional level, Health and Education Commissions began to oversee the progress of autonomous health care and education, and to develop local as well as regional infrastructure. After the Zapatista uprising in 1994, there was an influx of outside support that included donated medicine and school supplies as well as teachers and doctors who went to Chiapas to help train a generation of young health and education promoters. Even with this support, however, constructing an entire infrastructure was a huge undertaking, especially given the lack of resources in the rural indigenous communities of Chiapas.

Victoria, the Zapatista comandanta who was motivated to join the EZLN by the injustices surrounding the lack of health care, helped her community to develop its own solutions. Angered by the Mexican government turning its back on Chiapas’s rural poor, she worked in a health care center in her village and supported the establishment of autonomous health care infrastructure in her region.

In 1997, one of the compañeros organized a meeting and presented a proposal to build a health center in our village. We agreed with the proposal but we didn’t have any money to build the center and we spent hours talking about it. Finally one of the compañeros proposed that, in the meantime, we could try to use a house that belonged to the community. We all agreed and we asked this compañero to talk to the local representatives and the residents of the village. The community decided to lend us this house. Since there were already health promoters, some ofwhom were Zapatistas and some of whom were not, we told them that we were going to open a small health center and they were happy. We agreed that the health promoters who already knew enough to see patients would take turns, so the health promoters with less experience could learn from them.

In June 1997, our small health center opened and began to function. The compañeros each donated a bottle of tincture, and that’s how we got started, because we didn’t have any money to buy medicine. When the health center grew, we paid each of those three compañeros back for the bottle of tincture and we invested the rest of the money back into the center. I started going to the center because I wanted to learn more about medicine and the health promoter invited me to work there. I was hesitant because I still didn’t know very much, but I talked to the other woman health promoter and we agreed to work in the health center together. We began working there in August 1997.

Some people said bad things about us because we were women and we were unmarried. They said we were just looking for a husband. They said that when men came to the health clinic, we hid behind closed doors with the men, or that we closed the health center and went with the men to their houses. We thought we wouldn’t be able to stand it and we were going to quit because of the criticism and the gossip. But we helped each other feel better because we knew what they were saying wasn’t true and because no one else was going to keep the health center running. And we kept doing our work.

In June 1998, we built a bigger building for the health center. All the health promoters contributed and we used the money we had made in the health center. Men and women worked together to build the new center and we’re still working there today. We don’t give the medicine away for free, but we only charge enough to buy more medicine. It’s not like before, when there were no health promoters. Now we have our small health center, we have a small pharmacy that was donated, and what we built ourselves is still there.24

Angelica and Rosaura are also Zapatista health promoters, from the Morelia and Garrucha regions, respectively. At the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, they described the health conditions that motivated them to pursue this path. “People in our villages used to die from curable diseases,” said Angelica, “because there was no medical attention in the indigenous villages where we lived. The government only provided health care in the cities.”25 During the 1990s, in Chiapas’s state capital ofTuxtla Gutiérrez there was one doctor for every 397 inhabitants, whereas in the municipalities where indigenous people make up more than 70 percent of the population there was only one doctor for every twenty-five thousand inhabitants.26

“There was no money for transportation and there were no roads,” added Rosaura. “Sometimes we had to carry the patient on a stretcher made out of sticks or a hammock made from rope. And sometimes they didn’t make it to the hospital—they died on the way because we had to walk for many hours.”27

“We would arrive at the hospital and they wouldn’t give us the kind of attention we deserved,” continued Angelica, “because the doctors only wanted to treat people from the city. When we arrived, even if a member of our family was dying, or screaming with pain, they wouldn’t bother helping us, just because we’re indigenous. They didn’t want to let us into the hospital. Sometimes they would tell us that the hospital was full, that they couldn’t help us. But it was a lie. They just didn’t want to help us.”28

Rural indigenous women faced particular hardships. “The land-owners didn’t care if a woman was pregnant,” recalled a group of Zapatista women at a regional women’s gathering in Morelia, “so she couldn’t take care of herself after she gave birth. Women didn’t even get to rest. They would sleep one night and the next day they had to go back to work.”29

“When we got sick, no one took care of us,” described Rosaura. “Sometimes the man waited a long time to see ifhis wife would get better at home. If she didn’t get better, he would take her to the hospital, but only once she was gravely ill. A lot of women died, especially in complicated childbirths or after giving birth, because there was no health care and no one gave us information about how to take care ofourselves.”30

The indigenous communities had their own traditional knowledge about health and healing. “Before, health care wasn’t like it is now,” said the women from Morelia. “We didn’t buy any medicine. When someone was sick, they would look for medicinal plants. They knew about medicinal herbs back then and that’s how they got better.”31 There were practicing parteras (midwives), hueseros (bone-setters), and other types of traditional healers, as well as extensive knowledge of medicinal plants. When Zapatista women talk about traditional healing practices, however, there is a tension between appreciation for this knowledge and the fact that it was insufficient to ensure the health of communities contending with poverty, malnutrition, and the lack of access to hospitals and doctors. “In our villages, we had traditional midwives who could take care of normal births,” said Rosaura by way of example, “but they didn’t have good materials. They used tweezers made of sticks to cut off the umbilical cord. They used bitter herbs or hot herbs to make the birth happen faster. When the woman gave birth, they would warm her uterus with a clay pot so she wouldn’t have pain afterward. But for more serious circumstances, there was no way to get someone out quickly.”32

The rampant problems with sickness and disease in rural Chiapas became a motivating force for the Zapatistas to develop their own health care system. “The indigenous communities in resistance chose to fight for life and not wait for the death to which the government had condemned us,” said Magali, a midwife from La Realidad. “The people in these forgotten places decided to confront our health problems on our own.”33

The autonomous health care system began to emerge long before the Caracoles, even before the Zapatista uprising. Argelia, a health promoter from Oventic, explained:

The Zapatista autonomous health care system was born before 1994. It began when we realized that so many health problems in our territory were because of the lack of health care, the lack of clinics, hospitals, and doctors, and that so many people from our communities dying from curable diseases—men, women, children, and the elderly—were because we are discriminated against and left behind by the government just because we’re indigenous.

We began to analyze and come to consciousness about how to confront these problems and look for solutions. After several community meetings, we decided to form our own clinics and have our own health promoters and not depend on the government. We looked for a central location that could cover many communities and municipalities. Construction of the clinic in Oventic began in 1988 and the clinic began to function at the beginning of February 1992.34

Arnulfo, a member of the Health Commission in La Garrucha, explained how those early days helped lay the foundation for autonomy later on: “It was very difficult because there was still no road. We walked from one community to another. But it really helped us because those of us who participated in that original effort, we don’t need the government anymore. For example, now we know how to recognize different illnesses and we know how to give injections.”35

By the mid-1990s, the Zapatistas were consolidating these disparate grassroots efforts into a centralized autonomous health care system. Communities without health promoters were encouraged to designate them. Regional health coordinators organized trainings for the local health promoters and visited different villages to identify health care needs and to ensure community support. Increasing numbers of Zapatista villages began building local and regional health clinics.

The autonomous health care system evolved, over time, into a well-developed infrastructure at the local, municipal, and regional level. “Each community should have one or two general health promoters and also in each area of traditional medicine,” said Magali. “Each community should have its own casa de salud [community health center]. Some communities already have one but others do not, because of the lack of economic resources. Each community should also have a small pharmacy.”36 Often an unassuming structure, the casa de salud provides a physical space for the health promoters to see patients, hold meetings, and store herbs and medicine.

Most autonomous municipalities have their own clinic, staffed by health promoters from different villages who take turns staying there to see patients. Argelia used her region of Oventic as an example: “The autonomous health system in the highlands region of Chiapas includes seven autonomous municipalities. Each of the autonomous municipal-ities has a microclinic which facilitates access and communication.”237

Each of the five Zapatista zones, in turn, has a central clinic or hospital. These regional hospitals began as rudimentary rural health clinics but now most of them offer a wide variety of advanced medical services. “In the central clinic we carry out surgery on a regular basis,” said Elvia, a health promoter from Oventic.38 With the creation of an autonomous government for each of the five Zapatista Caracoles, the autonomous commissions began to coordinate their work at the zonewide level. In Morelia, for example, the regional Health Commission began to organize health promoters into brigades.

The autonomous health care system has heavily emphasized prevention. “The women health promoters hold a meeting with all the women and we explain to the rest of the women what we know,” said Luisa, a medicinal plants promoter from Francisco Gómez. “The first project we organized was to visit every house once a month and talk to each family about health: sanitary conditions, the latrines, the kitchens, and if they are purifying their water.”39

“The majority of microclinics have health promoters who are in charge of vaccinating people in the communities,” said Elvia. “It’s hard work because many places still don’t have roads and we have to walk from village to village. When it’s raining, we have to put up with the cold, the mud, and sometimes we go hungry.”40

Initially, the autonomous health care system focused primarily on Western medicine. The first generation of Zapatista health promoters was mostly young men and women who were trained by visiting doctors. With time, however, autonomous health care began to incorporate traditional practices such as the use of medicinal plants, and traditional healers like midwives and bone-setters. This was a gradual and sometimes challenging process. A long history of racism meant that indigenous communities had been taught to mistrust their own cultural heritage and much traditional knowledge had already been lost. Arnulfo explained:

Salesmen came here selling medicine and pills—that’s one reason people stopped using medicinal plants. Some people believed the pills were more effective. They work faster, to get rid of diarrhea for example. But now we know that they are not actually killing the real cause of the diarrhea. These pills, they sell them to us at a very high price and we don’t even know what they’re doing to us. And the people who stopped trusting medicinal plants, when they go to the doctor now they have to buy medicine. Sometimes they have to sell their horse or their cow to be able to pay for the medicine.

We have won back much more respect for medicinal plants. Many people have starting using them again. In fact, medicinal plants is the area where we have seen the most progress.41

Realizing how much knowledge they already had was an important step in this process. “The people here liked the idea of a workshop about medicinal plants because it can be very difficult to obtain medicine,” said Luisa. “I have been working with medicinal plants since we first began these courses. It was all women in the first course on medicinal plants and there were about forty of us. We had decided that we wanted to learn more about medicinal plants. We already knew all the plants around here—we just didn’t know the exact doses and how to prepare the treatment.”42 The young women did not think of themselves as experts in medicinal plants and had agreed to attend trainings offered by a nongovernmental organization. “But when the first course began,” Luisa continued, “we realized that we knew more about the plants than the woman who came to give the workshop! When we get together, just among ourselves, we have a lot ofinforma- tion and we all share what we already know.”

The autonomous health care system has supported ongoing efforts to recuperate and preserve traditional healing practices. “For example, the elders, they know how to cure tuberculosis and snake bites,” said Arnulfo. “This knowledge was of great use to our parents and grandparents. We want to rescue this knowledge before it’s lost forever. The knowledge has always been here but for a long time no one gave it any importance.”43

Aldai, an herbalist from La Realidad, explained some of the work being done with medicinal plants in her region.

We offer general consultations for the most common illnesses. We see patients in the casa de salud, where we store plants that we have collected and dried. Some communities still don’t have a casa de salud, so we go to the sick person’s house or we see people in our own homes.

We have learned to prepare tinctures, which are a way to conserve the healing qualities of medicinal plants for many years. Tinctures are also useful during the seasons when plants are not flowering. We also prepare pomades, soaps, syrups, pills, and drops for the eyes and ears. Thanks to a solidarity organization, we were able to construct an herbal laboratory, which is in the Caracol of La Realidad. This laboratory is where we process the medicinal plants because we don’t have the economic resources to do it in each village.

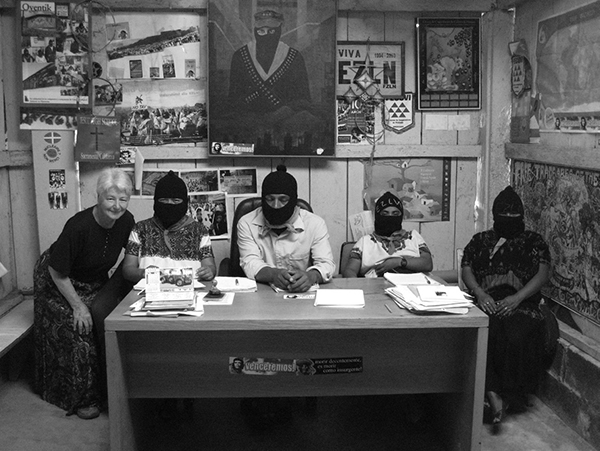

A mural depicting the autonomous health care system in Lucio Cabañas illustrates the use of medicinal plants as well as Western medicine. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)

We also saw the need for a botanical garden in each community in order to plant herbs we don’t have, and so this way of curing people with medicinal plants can never be taken away from us again. We give thanks to our elders who were still able to learn from our grandparents and our ancestors, and they are sharing what they know with us. Because even though we’re preparing herbal medicine in ways that are unfamiliar to them, the most important thing is that we’re using plants and herbs.44

Midwifery is an area of traditional medicine that saw much greater continuity. According to a study done by Physicians for Human Rights, almost nine out of ten rural indigenous women in Chiapas give birth in their homes and almost three-quarters of them give birth with the assistance of a midwife.45 Agustina, the treasurer of the women’s cooperative store in La Garrucha, is also one of two traditional midwives in her community.

I learned to be a midwife completely on my own. That’s how all of us who are older learned. Before, there were no courses to learn. The knowledge just came to me, in my dreams. All the older midwives say the same thing. We receive this capacity like a gift from God. The first child I received was my own granddaughter. At first I just tried to see how it would go, and then again and again. I have now received fifty-five babies and, thank God, not one has died. Now I’m not afraid anymore. We do this work to serve our community and we don’t ask for anything in return.46

Integrating traditional midwives into the autonomous health care system has been a mutually beneficial process. Younger midwives learn from their elders, and institutionalizing this knowledge means it is more likely to be handed down to future generations. The traditional midwives benefit from resources and support from the Zapatista health care system. The autonomous health care system has worked hard to effectively integrate traditional and modern medicine and, since most midwives and many medicinal plant healers are women, it is also honoring the traditional knowledge held by women.

The autonomous health care system has also prioritized improving women’s health. Zapatista women from the Morelia region described why it was life-changing for them to have access to women health promoters: “Sometimes with men, we feel too embarrassed to talk to them about our health problems. But with a woman, we can speak more comfortably.”47 A much higher proportion of health promoters are women now than when the autonomous health care system first got off the ground. Some women health promoters have been trained specifically in reproductive and sexual health, and women have taken on roles ofincreasing complexity and leadership. “Women health promoters participate in the transfer of patients, attending births, general consultations, ophthalmology, vaccinations, gynecology, herbal medicine, in the emergency room, and surgery,” said Argelia.48

The commitment to women’s health has grown stronger over time. There are now clinics devoted specifically to women’s health, like a women’s clinic in La Garrucha named after Comandanta Ramona, and increasing awareness of health problems like cervical cancer and prolapsed uterus (fallen womb), a condition most common in women who have had multiple childbirths and do heavy manual labor. Rural Chiapas has historically had extremely high rates of maternal mortality and the autonomous health care system has worked hard to change this. “We provide prenatal care during the pregnancy,” said Elvia. “We do home visits to women with highrisk pregnancies. In the central clinic and some of the microclinics, we are also attending births.”49

The focus on women’s health has also meant educating women about their own health. “When we were small girls, we didn’t know anything about women’s health,” said Comandanta Micaela. “We didn’t know how to take care of ourselves because no one explained to us what happens to girls during adolescence. But now girls know how their bodies will develop. Now we know we have the right to health care and that we must love and take care of ourselves.”50

The women from Morelia described reproductive health workshops where they learned about women’s bodies, different illnesses, and family planning. “The health promoters and other women who have gone to these courses share what they learn with other women,” they said. “They inform the other women how to take care of their health. But there are still many women who don’t know and still feel embarrassed. There are still some women who don’t explain anything to their children.”51

At the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, Rosaura discussed some of the health problems that women still face. “Many women still die, especially during or after a complicated birth,” she said, “and because of miscarriages, premature births, placental retention, sexually transmitted diseases, and cervical or uterine cancer.”52 Although these ongoing health concerns are significant, the fact that Rosaura could rattle off this list of women’s health problems, as well as her openness and confidence, reflected an advanced level of training—one that was not present in the earlier stages of the autonomous health care system and will be critical in addressing these remaining challenges.

During a collective interview in the autonomous municipality Lucio Cabañas, a group of women health promoters described the overall improvement they had seen in women’s health. “Women used to get sick more because their lives were so difficult,” they said. “If you have problems in your family, if you are upset a lot—you will get sick more often. Ifyou have fewer worries, you will get sick less. Now women participate in all areas of community life. Men and women have the same rights and men and women help each other in the home. That’s why women don’t get sick as much anymore.”53 These comments echoed other conversations I had with Zapatista women, community health promoters, and outside health professionals who described how opportunities for women in the public sphere lead many Zapatista women to delay marriage, develop more supportive relationships with their partners, put more space between pregnancies, and pursue greater opportunities for personal growth—huge lifestyle changes that have impacted their physical and mental health. They also identified an increased awareness of the importance of good nutrition, particularly for women of childbearing age, as a factor in improving women’s health.

Zapatista territory has seen a dramatic decrease in infant mortality. “Things have changed because before, children didn’t grow up,” said Ernestina. “Me, for example, I have eight children, and not one ofthem died. It wasn’t like that before. A child would be born and then die. There were hardly any small children. My mother, for example . . . One day my little brothers and sisters died, just like that. That was what life was like before. Sometimes two children would die in one day.”54

Building an autonomous health care system has not been easy. “We have been developing it for more than fifteen years,” said Argelia, “even though the process has been slow and with many difficulties along the way because of our lack of experience, the lack of economic resources, the difficulty with illnesses in the communities, and because the bad government confuses people with its ideas that go against the health and well-being of the population.”55 The lack of resources impacts everything from training community health promoters to building health clinics, from buying medicine to trans-porting patients in the case of emergencies.

The lack of formal education is also a significant obstacle, and the Zapatistas have never been able to meet their own goal of having community-based health promoters in every village. Arnulfo explained:

All the older communities have health promoters. Sometimes there are no health promoters in the newer communities, formed since 1994 on reclaimed land. We tell them it’s important to name health promoters but they don’t have any experience and they feel that they can’t learn. Part of my job is to encourage the new promoters, to remind them that all the knowledge and training doesn’t happen overnight—you need time, sacrifice, and commitment. We have succeeded in being able to treat certain illness, such as malaria, and this is very encouraging for the health promoters. It gives them hope. But it is also important to have patience. In the villages where the health promoters remain for a long time in their role, they see real progress. But in the communities where the health promoter changes every little while, they don’t advance much.56

Government health services have also become politicized in the context of the conflict. “After 1994, the government began to offer many things they had never offered before because they wanted us to sell out,” Arnulfo continued. The price of these new programs was loyalty to the government. People from Zapatista communities report being turned away from government health clinics and facing persistent discrimination because of their political affiliation.57 During the heightened tension between the EZLN and the Mexican government in the mid to late 1990s, under the banner of labor social (social work), the Mexican army was heavily involved in providing health care, which only deepened rural communities’ distrust of government health services. Furthermore, any village that refused these services was labeled Zapatista and treated with suspicion. The Mexican government has continued to use access to health care as a counterinsurgency strategy since then. It is not uncommon for the government to build a health clinic across the road from a Zapatista one, making it clear that its intentions have more to do with undermining the Zapatista movement than providing health services for a rural indigenous population that has been ignored for centuries.

In spite ofthe many obstacles, Zapatista health care has touched many lives. I don’t think he meant to boast, but Arnulfo was visibly pleased as he described the achievements of the autonomous health care system.

We continue to suffer from malnutrition—our limited diet is a big problem. But before, there was much more illness. I don’t have exact figures, but in the past many children died. They were not protected by vaccinations. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, and whooping cough, and also diarrhea killed a great number of children. But now these diseases have practically disappeared and we are ridding many children of the parasites that cause serious diarrhea. Now it’s very rare for a child to die from a serious illness or because we don’t have equipment or medicine. We have been able to save the lives of many people. Thank God that now we have the knowledge to help our people.

I see our progress and I feel proud ofwhat we’ve done. Now it’s not necessary to bring a doctor from far away. We still need outside support, there is much left to learn and a lot of equipment that we don’t have. But we are confident that we can learn—in fact, we are already doing it. Everything is possible with the tools and the training. For example, someone could be trained how to use a microscope or how to do ultrasounds for pregnant women. When we know how to do something, that’s when we feel that we are achieving autonomy.58

Lila was an adolescent in 1994 when the Zapatista uprising took place, and she attended a government-run school as a child. Now an education promoter teaching in the autonomous schools, she is able to compare the two systems.

Our autonomous education is very different from government schools because the government teachers teach us things that are not useful to us. They have their own reasons for being teachers—it’s not because they care about us as indigenous people. That’s why we created an autonomous educational system, so that children can be taught in our own language and according to our own culture. When I went to the govern-ment school, they did not teach us in our own language, and they beat us without mercy. If one of the children did not know the answer to a question, the teacher would hit him on the hands with a ruler. In the autonomous schools, if a child does not understand Spanish, we can explain in Tzeltal.59

I met Lila in the late 1990s, when she was a teenager. She was in La Garrucha for one of the first regional trainings for Zapatista education promoters. For several years, Lila was one of only two women education promoters in the entire region. Warm and inquisitive, Lila was a trailblazer for the new educational system, as well as for women.

Historically, many rural indigenous communities had no schools at all. “I never went to school, because I lived on the finca and the patrón didn’t let us study,” said a Zapatista woman from Santo Domingo. “He only wanted us to work. That’s why I don’t know how to read or write.”60

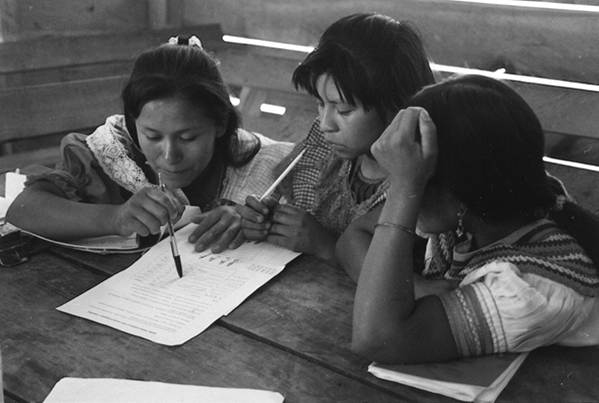

Even in the villages that did have schools, girls rarely attended classes. “When schools started to appear in some ofthe communities,” said a group of Zapatista women from the Morelia region, “girls were hardly ever allowed to go. The girls stayed home and did housework because they said we didn’t have the right to study. They said all we were good for was to take care of our younger brothers and sisters. Our parents said the boys could go to school and learn because they could become teachers or get another good job, but women were never going to go out and work anyway. That’s why so many older women don’t know how to read.”61 With time, some parents began sending their girls to school and many younger Zapatista women, like Lila, attended the government’s elementary schools for a few years as children.

The Zapatista communities, however, had serious concerns about the government-run schools: the poor quality of education, the mistreatment of children, and the lack of respect for indigenous language and culture inherent in Mexican education policy that, for most of the twentieth century, focused on assimilating indigenous peoples. “In the government’s educational system they only teach one language [Spanish],” said Mauricio, a member of the Education Commission in La Garrucha, “and we want to be able to learn in our own language. When we learn in their language, it means we have to speak their language and learn their ideas. In the official educational system, our culture gets lost. Indigenous children are not familiar with their own culture and they feel ashamed of being indigenous.”62 He explained how these concerns spurred the Zapatistas to develop their own autonomous educational system.

Autonomous education began as a response to our communities’ needs—it’s not like government education. We began by thinking about having our own education, among ourselves. We realized that we are forgetting how to count and do math in our own language. We began to think about our own educational authorities, having our own teachers. That’s how we began to dream about all this. And when the communities started to organize, that’s when we began. It really took offwith this struggle, with the organization [the EZLN]. We saw that if we were going to change things, we were going to change everything.

The autonomous education system includes education promoters and an elementary school in each village, as well as in some cases a local committee to promote education. Each community is responsible for building a school and providing economic support to the education promoters, often in the form of working their cornfields for them. An Education Commission coordinates the work in each autonomous municipality and throughout the region. In addition to the local elementary schools, there are now a number of regional high schools that function as boarding schools for children from surrounding villages. Before these regional high schools were established, it was rare for children from these indigenous communities to receive anything beyond an elementary school education.

As with the autonomous health care system, each community chose their education promoters, who were then trained at the regional level, and at first, many of them did not have the skills or training to be teachers. Isabela is a young education promoter from Santo Domingo. Like Lila, her village asked her to take on this responsibility when she was just a teenager.

My community wanted a promoter to teach the children. Before, the children didn’t know how to read or write, or even the alphabet, but now I’m teaching them the letters of the alphabet. I began four years ago. When I began, I thought it would be easy, but now I’m seeing how difficult it is. But I’m doing what I can and moving forward as a promoter. It’s hard because I don’t know how to read very well myself, I don’t speak much Spanish, and I don’t know much math. I learn more when I go to the trainings. I take notes and my notes help me later. They teach us methods for teaching the children. If I try to do it offthe top of my head it doesn’t come out very well.63

The Education Commissions help support and guide the local education promoters. Amelia was a member of the Education Commission in her region for three years before joining the Women’s Commission. She described to me some of her responsibilities.

There were four of us, and our work was to oversee education. We would go out and accompany the education promoters. I think it was 1999 when we visited the whole zone, together with our compañeros from the other municipalities in the region.64 We went to see how the education work was going, what kind of progress was being made, and what problems there were in each municipality. We were away from our homes for two months while we traveled throughout the whole zone.