Like many Zapatista women, Celina spent her childhood on a finca but now lives in an all-Zapatista village and farms on reclaimed land. One morning, I accompanied her to her family’s plot of land. We walked for more than an hour before arriving at her milpa, climbing hills, crossing a hammock bridge, and passing through other cornfields on narrow dirt paths. As we walked, she recalled the hardships of her young life.

My father worked very hard on that finca, and sometimes they paid him and sometimes they didn’t. We didn’t have corn, we didn’t have beans. We didn’t have coffee to drink because we didn’t have anywhere to plant coffee. We did whatever we could to survive—we sold firewood, we sold charcoal. But I didn’t think about all this until I was older. When I was younger, I thought that’s just how things were.

The EZLN arrived and told us that the government was oppressing us. They talked to us about land. There was never enough land for us—we only ever planted on the mountainside. No peasant or indigenous person ever farmed in the valley. So we started organizing—men and women. In the organization, they told us we should be working to organize other people.1

Despite having no formal education, Celina has held a number of different positions within the Zapatista movement, utilizing her natural ability to listen to others and to motivate them to act. “They had schools in some of the villages, but not on the fincas,” she said. “That’s why everyone who grew up on a finca—none of us know how to read or write.” Recognizing her own leadership qualities, she often said ruefully that being illiterate was the only thing holding her back.

After several hours of hoeing weeds in her cornfield, we took refuge from the midday sun in the shade of a tree. Celina took a ball of ground corn out of her bag and, as she mixed it with water to make pozol, she described one of the biggest transformations in her life— the changes that took place in her own family.

I used to think that only men have rights. I just did my work and was completely manipulated. I didn’t know anything. I was always at home and I thought the only thing women were good for was working in the house. When the organization [the EZLN] arrived, we began to wake up. I began to realize that life doesn’t have to be how I was living it. We heard that women can participate too. I already had children when I began thinking that the way we were living was wrong. I always thought things had to be that way, that’s just how life was.

In my family, things have changed a lot. My husband is completely different. Before, he didn’t want me to leave the house at all. He didn’t respect me. If he didn’t like something I said, he would mistreat me. But he’s not like that anymore. As a woman, I learned to speak up. I learned to defend myself. Both of us have to change, that’s what I realized back then. Men have to change, but so do women. Life in our home changed a lot. Now we understand that we both have to respect each other.

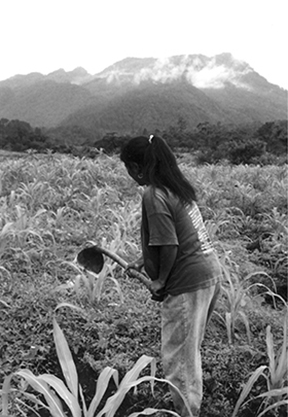

Celina, working in her cornfield. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

My husband worked with the organization, in the area of health care. Since they talked about women’s rights there, he started to think about it, and he began to change. He allowed me to leave the house. He even encouraged me to learn too, so both of us would understand more. He told me that it wasn’t just him that should learn, that I should learn new things too. Sometimes I didn’t want to go to meetings and he would say, “How will you learn if you don’t go?” He encouraged me. It wasn’t like that before. When he first began to participate, he didn’t want to bring me to meetings with him.

There are men who hear this message but don’t change their minds. But my compañero isn’t like that. He changed quickly. When they chose me for the Women’s Commission, he was away from home. But I accepted the responsibility and when he got back, he said, “If you already accepted, that’s fine. You know what you’re capable of.” He always tells me, “Go as far as you can.”

Although the EZLN has worked hard to increase women’s participation and leadership in the public sphere, some of the most remarkable transformations women have experienced have been within family life. There is a cause-and-effect relationship between the two—changes in the private sphere take place as women become more politically active, and vice versa.

A woman’s right to choose her own partner is now a well-established fact in Zapatista territory; it is one of the rights outlined in the Women’s Revolutionary Law that has been most fully implemented. “Now women decide who we want to marry,” said a young Zapatista woman from Miguel Hidalgo. “We get to know each other and now the man and the woman both get to choose. I got married when I was sixteen, and it was my own choice. My husband treats me well. If I had been forced to get married, we would probably be fighting all the time.”2

Zapatista women also exercise more control over how many children they have, and tend to have fewer children. “We didn’t have any kind of health care before,” said Agustina, the older Tzeltal woman from La Garrucha who has served as a midwife and the treasurer of the women’s cooperative store. “For example, God sent me twelve children. Now women know a little more about family planning, and they have two or three or four children. Many women plan their families. Others have operations not to have any more children.”3 Educational workshops and increasing numbers of women health promoters have meant that women have more information about reproductive health and family planning. On the other hand, women in the more isolated communities have limited access to contraception, and the history of nonconsensual sterilization at government clinics and hospitals has led to a deep mistrust of birth control obtained in those settings. The most common forms of family planning, therefore, include the rhythm method and other natural approaches. The tendency to marry a little later also means that women are likely to have fewer children. The Catholic Church’s offi-cial stance against contraception may continue to have an impact, and birth control tends to be more controversial with older women, but the Diocese of San Cristóbal has not overtly tried to influence women against family planning.

Zapatista women also describe a more general shift. “Women are treated better within the family,” said a group of Zapatista women during a regional women’s gathering in Morelia. “Now everyone is happy when a baby is born, whether it’s a girl or a boy. In the past, the daughter-in-law had to wake up earlier than everyone else and she had to work the hardest, but now things are better. Now our husbands and our in-laws are more loving. They respect us and treat us better.”4

Not all women’s stories are as straightforward as Celina’s, however. As I arrived in Morelia for a workshop with representatives of the women’s cooperatives in 1999, Margarita was on my mind. One of the coordinators of the women’s cooperatives, she had more experience than many other women and was an important role model for them. I thought about her sharp political analysis and her tenderness toward her children. I thought about her representing the EZLN at an international gathering and her shy laughter when I had congratulated her. But for the previous several months, she had been quieter than usual, and had missed the last workshop. When I asked her what was wrong, she mentioned problems with her family, but was vague. She was thinking about quitting her post, she told me despondently, and did not even feel like leaving her house some-times.

I knew that Margarita’s husband had continued to drink after 1994, not complying with the ban on alcohol in spite of his leadership within the Zapatista movement. I also knew that he was often abusive when he had been drinking. “Women feel bad when our husbands drink,” Margarita had once said. “It makes us angry because they yell at us or abuse us or hit us. That’s why sometimes we get discouraged in our work and that’s when we feel sad and locked up in our houses. Sometimes I can’t even eat because I’m so anxious. Maybe our husbands are not really thinking about the struggle and the freedom that we’re fighting for.”5 When I had these conversations with Margarita, I thought back to the years I had spent working at a women’s shelter in the United States, and how domestic violence can happen in any household, regardless of race, nationality, class, or sexual orientation. I guess it happens in “revolutionary” households too, I thought to myself.

What made Margarita’s situation more poignant was that when her husband was not drinking, they had a strong relationship. He acknowledged his struggle with alcohol and was often able to stop drinking for a few months at a time. He has always supported Margarita’s political participation and the mutual love and respect between them was tangible. I worked closely with Margarita for years and, with their three young sons scampering about the house, it was always a joyful home to visit. After the Zapatistas reiterated their agreement to ban alcohol yet again in the late 1990s, and with support from other Zapatista authorities, Margarita’s husband was finally able to stop drinking and his abusive behavior ceased. One of their young sons said to me, “We’re happy now because my father doesn’t drink anymore.”

Knowing this history, I could not help but wonder if Margarita’s husband had started drinking again. On that trip to Morelia, I went to visit her the same day I arrived, wanting to see how she was and hoping to ensure her presence at the workshop the next day. I headed to her house slowly, a fifteen-minute walk from the Aguascalientes into the village of Morelia, across a dirt road, up a hill, and past the small church. Arriving at her house, I leaned over the fence and called out to announce that she had a visitor. The dogs started barking and one of her sons poked his head out the door and told me to come in. Margarita was behind the house, washing clothes. She motioned to me to sit down and talk to her while she continued working. I asked about her husband, but that was not what was on her mind. “Don Arturo,” she said to me. It turned out that Arturo, her father-in-law, was the reason she had not attended the last workshop. He had told her not to leave the house and that she should be home caring for her family. Arturo, who was abusive to his own wife, was also advising her husband to beat her.

I asked about her husband’s response. He had told her not to listen to Don Arturo but he wouldn’t stand up to his father because, according to him, Don Arturo was old and unlikely to change. People are complicated, I reminded myself with an inward sigh. This was the same Tzeltal elder who had told me that he was not participating in this revolutionary struggle for himself because he knew he would not see the fruits of his labor in his own lifetime—that he was doing it for his children, his grandchildren, and future generations.

Recently, Margarita continued, Arturo had started making sexually suggestive comments and looking at her in a way that made her uncomfortable. That seemed to have been the final straw. “I told him that ifhe’s looking for another woman, well, go ahead and look,” she recounted, “but it’s not going to be me.” I asked Margarita ifhe had touched her, and there was a steely look in her eyes when she said, “No, but ifhe ever does . . .” Looking at her face in that moment, I believed that she would pick up a machete, a stick, or whatever else was handy, and defend herself with it.

After she stood up to Don Arturo, she said, things had improved. Her husband had agreed to build a separate kitchen so they would not have to share the same space. Margarita’s mother had promised that if anything happened, she would speak to the authorities, they would deal with it among the elders, and Don Arturo would likely be censured by his own peers. When Margarita was done washing her clothes and hanging them on the clothesline, she asked me in for a cup of coffee, but I told her that I still needed to prepare some materials for the workshop the next day. She promised me she would come to the workshop, and she did.

The process of transformation that Zapatista women have taken part in has not always been simple or linear. Freedom from violence is enshrined in the Women’s Revolutionary Law, and alcohol abuse and domestic violence have been dramatically reduced in Zapatista territory, though not eradicated. It takes time to establish a right, and then it is not always easy to exercise that right, but women have tools they did not have in the past. “Now women know how to defend ourselves and stand up for our rights,” said a Zapatista woman from the Roberto Barrios region at the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering. “Women are no longer mistreated by their husbands and fathers and, if there is some type of abuse or family violence, it can be resolved by the autonomous authorities.”6

The transformation of gender norms would not have been possible without the Zapatista communities’ ongoing willingness to examine their own culture. “There are two kinds of customs,” said a group of Zapatista women during a regional women’s gathering in Morelia, “good ones and bad ones. We want to hold on to our traditions that are good and let go of ones that are bad, the ones that are harmful to us as women.”7 For the Zapatistas, culture is a cornerstone of indigenous resistance. “We want to maintain the customs of our Mayan ancestors. As women, we play an important role in learning and rescuing our customs and traditions. We want to maintain things in our culture like respecting the elders and dancing to traditional music.” The Zapatista women expressed appreciation for their cultural heritage, and a sense of loss for some customs that are no longer practiced. “They used to have ceremonies and everyone danced. They had great respect for the sun, the moon, the caves, the wind, the rain, the streams, and the hills where the spring begins.

When they had celebrations in the caves at the water source, they would bring candles, incense, a flag, and firecrackers. The celebration was to ask for the rain to come and also for a good harvest. They played traditional music with a harp, guitar, violin, and drum.”8

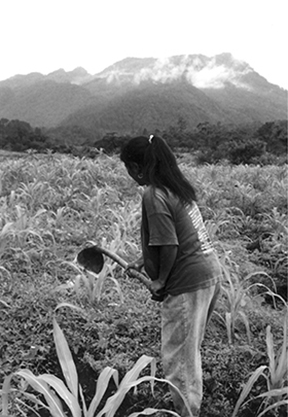

“We see these customs as a very positive thing,” Comandanta Micaela told me, “because they knew how to do everything themselves: sew their own clothing and make pots out of clay. They did everything with their own hands.”9 A group of Zapatista women in an artisan cooperative affirmed: “It’s important for us to make artisan crafts because it’s our custom, our tradition. Our mothers taught us how to embroider. Our ancestors wove with looms and we don’t want to lose that tradition.”10 Respect for their ancestors’ culture, however, is sometimes tainted by associations with poverty or scarcity. “Women didn’t have any money to buy things,” said the women from Morelia. “They used plants for washing because they didn’t have soap. When they bathed, they used white mud or the roots of a plant. They washed their clothes with ash and they didn’t use chlorine. They used bowls and pots made out of clay. Spoons were made of sticks and combs were made of wood. Women didn’t wear shoes—they went barefoot. Sometimes the men wore sandals made from cow leather, but the women were always barefoot.”11

Zapatista women, therefore, seek to combine positive elements of their culture with newer innovations. “We want to learn Spanish but not forget our indigenous languages,” added the women from Morelia.12 Zapatista women fight to protect indigenous culture in general, while altering the practices that oppress them as women. “We want to reject the bad customs,” the women continued. “Bad customs are things like witchcraft, forcing young women to get married, and when a man has two or three wives. Now a young woman can choose her partner, and fathers don’t sell their daughters. We’re used to the way things are now and we don’t want to go back to the way it was before.”

Zapatista women have consistently defended their cultural identity while critiquing problematic practices within their own communities. Because of pressure from the Zapatistas and other groups of indigenous women, the definition of autonomy in the San Andrés Accords includes indigenous peoples’ collective rights and women’s rights: “Indigenous communities have the right to free self-determination and, as an expression of this, to autonomy as part of the Mexican State, in order to: . . . Apply their normative systems in the regulation and solution of internal conflicts, respecting individual guarantees, human rights, and in particular, the dignity and integrity of women Elect their authorities and exercise their internal forms of government according to their norms within the scope of their autonomy, guaranteeing the participation ofwomen in conditions of equity.”13 In other words, Zapatista women have demonstrated that defending indigenous culture and women’s rights need not be mutually exclusive.

In a speech to the Mexican Congress in 2001, Ester, a Zapatista comandanta from the Huixtán region, responded to the criticism that traditional indigenous authorities could use the San Andrés Accords to deny individual women their rights. “It is the current laws that allow us to be marginalized and degraded,” she said. “In addition to being women, we are also indigenous, and, as such, we are not recognized . . . That is why we want this law on indigenous rights and culture to be passed. It is very important for all the indigenous women of Mexico. It will mean that we will be recognized and respected as women and as indigenous people.”14

During her speech, Ester also spoke of the ongoing, collective process within Zapatista communities of analyzing which customs they want to maintain and which should be eliminated. “We know which of our customs and traditions are good and which ones are bad,” she said. The EZLN acknowledges that culture is dynamic, not static: the Zapatista movement is well known for blending the traditional with the modern, and this critical eye toward their own cultural practices contributes to an indigenous culture that is based on ancient customs but open to change. The Zapatistas also have a narrative, which may be something of a historical oversimplification, that patriarchy and its sexist practices were introduced into their communities by colonialism, and are not an intrinsic part ofindigenous culture.

Regardless of the origins of the problem, the Zapatista movement has grappled with undoing centuries of sexism but, as Isabel’s story will highlight, this is not a simple task. When she was a high-ranking member of the Zapatista army, Isabel wielded considerable military and political power.

Older Zapatista women teach younger women the traditional art of backstrap weaving. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)

A Zapatista woman prepares to cook over a fire, in the village of Morelia. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

A Zapatista man lights candles during an indigenous ceremony. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Indigenous women dance during a traditional festival. (Photograph by Hilary Klein.)

Once I had greater capacity and was given the responsibility to command—well, not to command, but to work with a whole region made up of many communities—I returned to the role of consciousness-raising, but now with the power to reach many more people. There was space to do the work in that region. Together with other women, we advanced the equality of rights and opportunities between men and women. We worked with men and we also changed what we were teaching our children. For example, if a woman is behind on the domestic work, the man can also feed the animals and take care of the children. He can be involved in that work as well. Those are the men who are really putting into practice what the Women’s Revolutionary Law says. For me, that’s a step forward. Also, the rejection of violence against women. Now there are men who will stop and think before they hit a woman. “Should I be doing this or not?” This is something that never would have happened before.15

Isabel, however, was demoted in 2003, for reasons she did not feel comfortable sharing during an interview. She chose to leave the insurgent army rather than accept the demotion, returned to her childhood village, and continues to collaborate with the Zapatista movement as a civilian. Her voice was bitter as she described the frustration she felt upon arriving back home.

You know, all this work to change people’s minds is not finished, because there is still resistance from men. When I returned to my community after nineteen and a half years committed to the struggle—where I spent my youth, where I gave everything I had, and after everything I went through—I returned home and I realized that all this, everything I’ve been talking to you about, well, that men still don’t understand. Maybe there’s resistance and men don’t want to change. I won’t say that men don’t take women into account—they do. But it’s as if men have set a limit, “up to here.” When a woman makes a decision, if it’s not in the men’s interest, they will override her decision. It’s their way of saying, “You’re not really in charge—we’re still in charge here.” If the women in the community suggest something and it’s convenient for the men, they will agree to it. But if the men don’t like it, they will put a stop to it. They continue on with their own plans, with their own rules. They rip our ideas apart and throw them out, and do whatever they want. We are left standing to one side, like spectators, watching to see what the men will do, and feeling like they don’t want something that is truly fair and just, and so—there we are! With no power and with the men still in charge. But when they need us to be part of the struggle, for example to confront the soldiers or some other danger, well, then they have to accept that they need us. They call us and say, “We need you to do this.”

But this doesn’t only happen with men in the villages. It happens in all different spaces, in the life of a combatant as well. Most men are not willing to see a woman surpass him. He is afraid of a woman giving him orders, afraid of a woman who is smarter than him. And even at the highest levels, they’re not willing to . . . Especially when a woman . . . Sometimes you have to make the decision to leave, to no longer share a space where men . . . Once you have realized that you can’t do any more . . . You see, I got to a point where what lay ahead of me was a fight. If you want to confront it, you can fight, and if not, well, you can step aside.

Isabel’s voice began to falter and she became emotional as she described her decision to leave the insurgent army. We turned the tape recorder off and talked for a while before continuing the interview.

Maybe it was a mistake, or maybe it was for the best, so I could continue participating and growing and sharing in other spaces instead, where I am accepted, where I feel like at least I’m planting something in other people’s hearts, with people who I love and who love and support me. I don’t know. That has been my life, and the greatest obstacle in my life. Maybe it was also my greatest failure, to no longer want to fight within that space.

It was very difficult. It’s still difficult. But in that time period I was telling you about, when we advanced so much in women’s organizing and we worked so hard to make women’s rights a reality, it was because there were women who were dedicated to the work and we gave it our all. There were many of us who gave everything, who sacrificed [laughter and a pause] . . . who spent our youth within that space, doing that work. We don’t have children. Many of us never married, because we gave everything to the struggle. And that’s how we were able to do what we did. For some women it was easy. For others it was very hard to choose not to be married, not to have children, not to have our own home, you know? But it was for the love of our people and so that we could move the work forward. What we have achieved has involved many people. But behind that there are women, women who gave everything.

The Zapatista movement has done much to promote women’s rights, but changes do not always come easily, inside or outside the organization. Isabel’s painful experience is an example of just how hard these struggles can be for individual Zapatista women, and the difficulties women face even within the upper echelons of the EZLN. “Many women have developed a consciousness about their rights, and some men too,” said Comandanta Micaela, “but there’s still a lot to be done. Even if they know about their rights, many women are still afraid to speak up or to accept public positions. They don’t participate much in the assemblies.”16 Even within the arena of public participation, which has been the Zapatista movement’s primary focus with regards to women’s rights, there have been ebbs and flows, changes have been uneven across different Zapatista regions, and significant challenges remain.

Women continue to face resistance from men, sometimes subtle, sometimes overt. “I have seen that women can be involved in the movement,” said Carlota, the regional coordinator from Olga Isabel who brought her case of domestic abuse to the autonomous Honor and Justice Commission. “Some men still don’t want to accept this, but we know what our rights are and we’re going to participate, whether they like it or not.”17 Although increasingly few in number, some men still try to prohibit their wives or daughters from any type of public or political participation. Women authorities sometimes receive less respect or support from their community than their male counterparts, ranging from derisive comments made in an assembly to the community paying the male authorities’ transportation costs but not the women’s.

Men and women authorities have the same responsibilities, but women are also expected to organize specifically with other women. They often have to prove their ability to do the same work as men, and they struggle to be respected equally as authorities. If they take on both sets of responsibilities, they have more work to do. But if they focus primarily on working with women, it can reinforce the perception that men are the “real” authorities and women authorities are “only” working with women.

Many women continue to face tension between their involvement in the Zapatista movement and their family obligations, and must sometimes choose between the two. “I asked one of the women comandantas whether having a small child made things more difficult,” recalled Esmeralda, the former nun who works closely with indigenous Zapatista communities. “‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I can’t do it. It’s not the same.’ ‘And your husband, who’s a comandante,’ I asked her. ‘Doesn’t he help you?’ ‘Ha!’ she answered. ‘No! He gets mad when he has to change a diaper.’ Some women comandantas, from the northern zone for example, they stopped participating after they had children. They stepped down. So yes, there’s still a lot of work left to do.”18

Women’s participation also fluctuates over time. I once asked a woman from the village of La Garrucha why there were no women milicianas in her community. “Oh, but there used to be,” she responded. In fact, she had been one of them. She told me that before 1994, there were a number of women milicianas, and that all women, milicianas or not, received military training. The uprising was already being planned and everyone expected a violent crackdown. The community was well aware of the possibility that soldiers would attack their village and try to rape the women, and both men and women wanted women to be able to defend themselves. The men stayed home and watched the children while the women went up into the mountains and were trained, she told me. I was incredulous. I had rarely seen a man in La Garrucha hold a baby, much less take care of his children while their mother was not home. “It was borne out of necessity,” she explained. Changes took place because of historical circumstances, but when the situation became somewhat normalized again, those changes were difficult to sustain.

In another example, Esmeralda described dynamic organizing work with women in parts of the northern zone while the EZLN was still a clandestine organization, but this diminished substantially after 1994. By the late 1990s, in the same regions where women had previously been highly organized, some women authorities had stopped participating altogether. “The organization was not working with women like it had in the past,” said Esmeralda, “and neither was the church. In other words, no one was taking an interest in motivating the women, or accompanying them. I think the presence of [the paramilitary organization] Paz y Justicia had a big impact as well.19 There was a great deal of fear in the communities.”20 Esmeralda went on to say that since 2003 or 2004, the work with women had grown stronger. “The organization put more effort into working with women again. I don’t know how things are in the whole region, but where I’m working there’s a decent level of participation and more consciousness about women’s rights and equality.” These two examples of the ebb and flow over time both demonstrate the influence of external circumstances, and that these circumstances can trigger an increase or a decrease in women’s organizing. Low-intensity warfare, while creating some situations that have pushed women to the foreground, is designed to undermine the communities’ social fabric, and has taken a particular toll on women’s public participation.

Zapatistas often refer to 1994 as a turning point and, to be sure, it was a watershed moment. The years just before and after 1994 were a dynamic period in Zapatista territory, and a tremendous amount of change was compressed into a very short period. In the intervening years, things have continued to change both in the public and private spheres but not at the same pace. On the one hand, the changes Zapatista women have already experienced give them hope and confidence about victories still to come. On the other hand, there is an element of impatience stemming from having reached a kind of plateau. Women’s deep loyalty to the EZLN brushes up against their frustration with a commitment to equality that has yet to be fulfilled and a vision of liberation that has yet to be realized.

Celina, Margarita, and Isabel’s stories demonstrate a range of experiences and the contrast between how much has changed for women in Zapatista territory and the obstacles that remain. There is no question that the EZLN has played a key role in the advancement of women’s rights, but the Zapatista movement and its approach to women’s liberation has also evolved over time. Rhetoric about women’s rights can pave the way for concrete changes, but there is almost inevitably a discrepancy between bold declarations made by the (often male) leadership and the reality of women’s lives. This discrepancy can become a source of frustration, inside and outside the movement, depending on how far reality trails behind the rhetoric, how fast it is catching up, and whether the rhetoric is perceived as a real commit-ment or an empty promise, taking the place of meaningful action. By the late 1990s, the EZLN’s leadership began to recognize the discrepancy between rhetoric and reality—an important step in and of itself—and to engage in a number of new strategies.

Civil society acted as a mirror and may have played a role in the way Zapatista leaders openly acknowledged this discrepancy. As we have seen, women’s rights and strong leadership from women have been hallmarks of the Zapatista movement since 1994. It was not uncommon, therefore, for outside supporters to visit Zapatista territory and be surprised by the level of women’s subordination still evident in their communities. Originally enthusiastic about the Zapatista movement and the space it opened for non-Zapatista women, a number of women’s rights organizations based in San Cristóbal grew frustrated with the disparity they saw between the EZLN’s words and its actions.

In August 2004, the EZLN published a series of communiqués commemorating the one-year anniversary of the Good Government Councils and assessing their first year of work. One communiqué, called “Two Shortcomings,” identified the low level of women’s participation as one of two major problems in the autonomous governments (the second being the ongoing role of the EZLN’s political-military structure). While Subcomandante Marcos did not directly respond to civil society’s critiques on the subject, the communiqué was clearly written for an outside audience. Marcos wrote that “the place of women” is one of two flaws “which seem to be chronic in our political work (and which flagrantly contradict our principles).” He went on to say:

The participation of women in the work of organizational leadership is still small, and in the Good Government Councils and the autonomous councils it is practically nonexistent . . . While the percentage of female participation in the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee in each zone is between 33 and 40 percent, in the autonomous councils and the Good Government Councils it averages less than 1 percent. Women are still not taken into consideration in the choosing of ejido commissioners and community police officers. The work of government is still the prerogative of men. . . . And it’s not just that. Even though Zapatista women have had a fundamental role in the resistance, respect for their rights is still, in some cases, just a declaration on paper. Domestic violence has decreased, it’s true, but more because of limitations on alcohol consumption than because of a new culture of family and gender. Women’s participation in activities that require them to leave their village is also still being limited. It’s not something written or explicit, but a woman who goes out without her husband or children is frowned upon and thought poorly of. . . It’s a disgrace, but we have to be honest: we don’t yet have a positive report to share with regards to women—in creating conditions for their development, or in a new culture that would acknowledge women’s skills and talents, ones that are supposedly exclusive to men. Even though it looks like it will be awhile, we hope one day to be able to say, with satisfaction, that we have been able to change at least this aspect of the world. For that alone, it would all have been worth it.21

Compared to his other communiqués about women in the Zapatista movement, Marcos’s tone in “Two Shortcomings” is somber and humble.

Regardless of this official shift in tone, Zapatista women are very careful about sharing any concerns they may have with outsiders. Understandably, they feel protective of their organization, since the EZLN spent many years as a clandestine group and still faces concerted efforts by the Mexican government to destroy it. This does not mean, however, that an internal dialogue is not taking place. With people they know and trust, Zapatista women will privately share their assessment of their movement’s strengths and weaknesses with regard to women’s rights. More importantly, women are organizing and exerting pressure within their own movement.

This pressure from within has resulted in an ideological shift in the Zapatista movement that has led to, for example, a successful expansion of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. It would be difficult to underestimate the significance of the Women’s Law as a tool for change in Zapatista communities. Written as it was in 1993, however, Zapatista women saw the need to expand it. “There were many other points that we realized should be included,” said Isabel. “New proposals began to emerge. In the case of divorce, for example: Who has the right to the land? Who keeps the children? The Women’s Law had to be expanded to incorporate these new proposals.”22 The exact text of the expanded law has not been made public, but it includes women’s right to own and inherit land, their right to recreation and rest, and their right to defend themselves from verbal as well as physical abuse. It also states that widows, single mothers, and single women should be respected by their communities and that, in cases of marital separation, land and other resources should be divided equally. “I think we should continue doing this,” added Isabel, “broadening [the Women’s Law], analyzing it, making it stronger and better.”

The Zapatista movement has also experimented with additional strategies to achieve a greater level of gender equality. These include consciousness-raising work directly with men, encouraging men to share the domestic work, and raising children with different ideas about gender.

For several years, Rudolfo was the coordinator of La Garrucha’s regional cooperative store. This involved overseeing a revolving loan fund that lent money to other villages to open women’s cooperative stores. Rudolfo was an important ally to the women involved in the cooperative stores, which was not always easy. Other men in his village consistently criticized him, but he held his ground. In community assemblies, he told the rest of the men that they should allow their wives to help run the store, and he accompanied the women to the nearest city to show them how and where to buy merchandise.

Rudolfo and I held regular training workshops with the men and women who ran the local stores. As previously mentioned, although these stores were women’s cooperatives, in villages where no woman had enough formal education to manage the accounting, the community would ask a man to be the store’s administrator. During a workshop in 2001, we began the day with all the participants together, using calculators to do accounting exercises. Some of the women, especially the older ones, felt intimidated at first. Most of them learned quickly, however, and were delighted by their ability to do complex math that was useful for running the store. That morning, one of the older women’s hands hovered hesitantly over her calculator. A young man leaned over, took the calculator out of her hand, and did the task for her, saying, “See, that’s how you do it.”

A little later in the day we divided into two groups; I worked with the women and Rudolfo worked with the men. Once in our own group, the women began talking to each other in Tzeltal, clearly agitated, so I asked them what was wrong. We talked about the young man taking the calculator out of the older woman’s hand and why they wanted the cooperatives to be an all-women’s space in the first place. After a brief discussion, the women decided that Rudolfo should speak to the other men. During lunch, while sitting in the shade of an ancient ceiba tree and dipping corn tortillas into plates ofbeans, they explained to Rudolfo why interactions like that made it harder for the women to learn, even if the men were trying to be helpful. Rudolfo was silent and thoughtful. He seemed a little reluctant but agreed to talk to the other men.

At the end of the day, the group came back together and there was almost an exact repetition of the morning scenario. While doing an exercise with the calculators, some women took longer to finish. One of the men began to lean over and say, “No, look, do it like this,” but then another man elbowed him and murmured something under his breath. The first man looked abashed and quickly drew back. The woman finished her exercise on the calculator, by herself and at her own pace. The rest of the women glanced at each other, looking extremely pleased.

A minor event in the larger scheme of things, it felt meaningful to everyone in the room that day. A number of elements had come together: a group of women whose assumption was to stand up for themselves, a male ally who was willing to act, and a group of men comfortable with being challenged and able to modify their own behavior. None of these things are unique to the Zapatista movement, but that day it seemed clear that the Zapatista movement was responsible for these elements being in place.

Since the beginning of the Zapatista movement, the EZLN’s leaders have carried out political education around women’s rights with men and women, but the more in-depth consciousness-raising work had mostly been done with women. By the late 1990s, there was a growing realization that to truly transform gender roles and relationships of power, the engagement with men had to be more intentional. “There is a lot ofwork to be done with men,” said Esmeralda, speaking about her experience with Zapatista communities. “You will see women who are strong and capable, but they bump up against problems with their husbands, or with other men who criticize them, telling them that what they’re doing is wrong. If we don’t address it, women will continue to face these kinds of obstacles. Men need to change too. The women need to change, but so do the men.”23

Zapatista women have pushed for deeper changes and experimented with new strategies. Under the direction of a woman in military leadership in the Morelia region, for example, a pamphlet titled Igualdad de derechos y oportunidades entre hombres y mujeres (Equality of Rights and Opportunities between Men and Women) was written and distributed in the Zapatista communities in 2001.24 It was designed to spark discussion about how to achieve gender equality, and gatherings were held in each of the region’s seven autonomous municipalities to study the pamphlet. Both men and women attended these gatherings, which was significant because in the past such a document would likely have been analyzed only by women. The document acknowledges that both men and women have faced racism and poverty, and asks men to put themselves in women’s shoes. During one gathering, a woman comandanta asked the men if they remembered ever being made to feel small by someone else. The men said yes, especially at the hands of landowners and the police. She then asked them to relate those experiences to what the women were describing. In another conversation, participants said that sexist ideas had been imposed on them for many generations, which is why it takes time to change, but they also pointed to encouraging examples ofgender equality, as seen among men and women insurgents.

Some Zapatista regions also began requesting that nongovernmental organizations develop programs to work with men around gender socialization. Esmeralda related:

Zapatista women have told us, “We understand about our rights, but if men don’t change, we’re not going to get very far.” Recently they told us, “We want workshops on gender, but now we want them to be for men and women.” In the northern zone, for example, we have scheduled a workshop on masculinity. We are going to invite the political authorities, the members of the autonomous councils, and anyone else who wants to attend. We’ll see how successful it is. We had one here and they liked it. Sometimes the men say, “Well, what about men? Don’t we have rights?” [laughs] “Only women have rights?” So when they start saying things like that, we respond by asking, “What rights do men have? Do they have rights or not? What illnesses do men have and why? What about the problem with alcohol? Where does machismo come from?”

In one of the workshops with women, we were talking about the right to decide how many children to have, and there were some men present as well. The women were all very clear: “However many children she wants to have, whether it’s more or less, but the woman should decide how many children to have.” And the men said no. “A woman should have however many children God sends her. When a woman wants to use birth control it’s because she’s trying to cheat on her husband.” That started a heated debate. And these are Zapatista men I’m talking about! It makes you wonder, what about the men who are not Zapatistas?25

At a gathering between the EZLN and civil society in 2006, a member of the audience asked what the Zapatistas were doing to change attitudes of machismo. Beto, a male member of the Good Government Council in the Morelia region, responded:

It’s a difficult thing, and a very slow process. Machismo has been around for a very long time. We have realized that this is a great mistake, and so first we have to recognize, as men, that we are a little bit sexist. I think the only way to change is through our consciousness. In other words, it won’t happen by punishing people, or putting them in jail, but rather through educating ourselves from below. And we have to begin with ourselves. As authorities, sometimes we have sexist attitudes. But I also believe that we are recognizing and learning that that doesn’t work, that it shouldn’t be that way.26

In a conversation with me in his region of Santo Domingo, Pacheco, who served on the Honor and Justice Commission before becoming a member of the Good Government Council, talked about the evolution of his own consciousness with regards to women’s rights.

Before, when I was eighteen, twenty, twenty-five years old, I didn’t know that women had rights. I thought that women didn’t have the right to speak up, only men. I thought that when women spoke up, well, that they didn’t know anything. My ideas began to change because I like to ask questions. When I don’t know something, I ask. With the organization, I began to see that women can speak up, so I asked questions in order to understand. We look to our own experiences, the seed is planted, and my ideas began to change.

I still hadn’t changed much by 1994. But in 1994 we all heard that women have rights and we began to walk on the right path. Women began to participate in autonomous health care, in education, in everything. We began to understand that women should be part of the struggle and that, as they gain more experience, we will all leave behind our bad customs. Before, mothers and fathers did not let their daughters leave the house, but now things are changing, and I have seen that women have the ability to struggle, to work, to speak up.

My two daughters have public responsibilities. One is a member of the autonomous council and the other is a coordinator of the artisan cooperative. I felt that it was important for them to learn, for them to leave behind the bad custom that women only work in the kitchen, and to get past their fear. I tell them to work hard, to learn as much as they can. I encourage them to ask questions whenever they don’t know something. I give them their freedom. Before, young women didn’t have much freedom. But I want them to gain experience, so they can still learn, even though they haven’t been to school.27

Compared to their mothers and grandmothers, Zapatista women generally have much greater freedom in their lives and face a less oppressive workload. But being a subsistence farmer is still a precarious existence that requires a grueling amount of work, and there is still a gendered division of labor. A young Tzeltal woman from the Zapatista region of Santo Domingo described an average day in her life.

Since my husband works in the fields, I get up early, at two or three in the morning, to grind corn, warm up the coffee, and make pozol for him to take with him. I work in the fields as well, planting beans, harvesting the coffee. We work hard to have food to eat that we grow ourselves. We don’t buy our food. We leave the house at six; we leave together and come back together. When we get back from the fields, I still have to prepare the food—make tortillas and feed my children. I get up early and I don’t stop working until ten or eleven o’clock at night, until I go to bed. I also have to take care of the children, carrying my smallest child with me in the fields. Even though I have a baby, I still have to work. We sell some of our harvest to have a little money. But we never get a fair price for our products, so we’re still poor.28

Multiple factors can influence a woman’s workload: whether or not she lives on the more fertile reclaimed land, whether or not her village

has potable water, and how many children she has. For example, at the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, a Tojolabal woman from the Morelia region described the impact of having access to clean water.

We used to carry our water from very far away because there was no water close by. We had to walk half an hour carrying our jugs and a bucket, and carrying our babies too. After we got home with the water, if we had time, we would gather the clothes and go back to the river again to wash clothes. We would go with our children to bathe in the river because there was no water close to our houses. Women had to carry the clothes balanced on their heads—the blankets, diapers, everything she had to wash. After she finished washing the clothes, she had to bathe her children and then walk back home with the clothes, the blankets on her head, and carrying her baby as well.29

A Zapatista woman washes clothes in a river near the village of Diez de Abril. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

Solidarity projects have helped install water systems in over a hundred Zapatista villages. In addition to improving these communities’ overall health by providing access to clean water, women in these villages no longer have to walk miles every day to fetch water from a river or stream.

On a cold day in 2006, I interviewed five Zapatista women in the autonomous municipality Miguel Hidalgo. I met Eva and her daughter-in-law Amelia in the municipal center where they live. Nora, Paula, and Guadalupe all live in nearby villages and had walked there that morning. Paula, the Zapatista woman who had worked as a servant before returning home at her father’s request, was the most cheerful and talkative of the five. Nora was about the same age as Paula but smiled less—the lines on her face hinted at her difficult life. Guadalupe was older and spoke less Spanish than the other women. We gathered in the autonomous schoolhouse, a dusty concrete building, and sat in a small circle in plastic classroom chairs. As we talked about their experiences growing up, and how they had become involved in the Zapatista movement, each woman addressed me directly, responding to my questions. Once we began talking about whether or not their husbands did any domestic work, however, and when they realized their experiences within their families were so distinct, the women turned to each other and engaged in a dialogue that became quite emotional.

Eva: In my family, we help each other. With my daughter-inlaw [Amelia] who lives with me, I help my son make food for the children. I help out since I’m their grandmother.

Nora: It’s difficult for the women who are alone with their children. If there’s a daughter-in-law or a mother-in-law who can help a little, then we’re able to participate in the organization. For example, I have chickens but they feed my chickens when I’m gone. My mother-in-law can’t do much anymore but she helps a little. But it’s still the women who help each other out with the housework. What men are going to do it? Maybe there are some men who do, but not my husband. If he’s there, he goes to work in the fields. He sees to his animals, he does other work. But he never worries about his children and whether they’ve eaten or not. It has to be another woman. At least that’s what I’ve seen. If someone helps us at home, then we can do it, like when I was a regional coordinator for three years. I have a sister-in-law who gave me a hand. I would go to the Caracol for a week at a time, but it always made me sad to leave my children. “And my mother, where did she go?” my little ones would ask. “Why isn’t she here?” They’re young, so I always worried about them. Someone was there to feed them, but it’s not the same as being with their mother.

Paula: In my home, things have changed. The men help a little too, when they have time. My husband helps—he grinds the corn. He’ll grab a pan and refry some beans and that’s what he’ll eat. Since we met through the organization, I think he already understood. He helps me with some things, when he can. He grinds corn and he also makes the nixtamal [limed corn to be made into tortillas]. He does everything but make tortillas—he still doesn’t know how to do that. Grind the corn, yes. Carry some firewood, yes. Carry water, he’ll do that also, if he has time. These are all things that men didn’t used to do. In my house, things have changed. But there are some women who say their husbands don’t want to do anything. They even have to give them water to wash their face.

Guadalupe: My husband doesn’t do any housework. I’m on my own. It’s hard for me to participate because sometimes I get sick, or because of the children. Even though I want to go to the meeting, sometimes I’m too behind on my housework. My children are still small. Who would stay with them? Their father isn’t concerned about whether they’ve eaten or not. I have to take care of them. He doesn’t help me, like what this other compañera is saying, that her husband helps her out.

Thank goodness he helps her, but not my husband. To tell you the truth, he doesn’t. It’s just me. [“Lack of consciousness,” interrupted Eva, somewhat disdainfully.] I do all the work by myself—carrying water, carrying firewood, all that. Nobody helps me. So that’s why I get behind, because I have so much work. I have to cook the beans, the corn, I have my two chickens and I have to give them their corn. The day goes by and I run out of time, but what can I do? I would like to go to the meetings, it’s not that I don’t want to participate. If I’m in my kitchen all day, I don’t learn anything. I don’t understand a word of Spanish. But if I go, I’ll understand, even if it’s just a few words, and those few words are worth something. If I have time, I go to the meetings, if there are meetings here in this municipality. My oldest son is ten years old. After that I have a daughter who’s eight, the next is six, then four, then two. I have five children. The ten-year-old helps a little—he makes pozol for the others. I want to raise them to be more equal. I always give my sons some housework to do because their father doesn’t want to do anything. Even after he’s rested for a while, he doesn’t even want to shell corn. I tell him he should shell a little bit of corn. “You have two eyes,” I tell him. “You have two hands, so you should do some work around the house.” My husband won’t do it, but my son obeys me. I won’t lie, my boy does help.

Eva: Since I had all sons, they learned to make tortillas, especially my youngest son. He cleaned, he made tortillas, he put the beans and corn on to cook. Ever since he was small, he valued the work that women do. The other boys didn’t do much. They only wanted to take care of their sheep. Before the organization [the EZLN], the mother had to do everything, but recently there have been many changes. I’ve seen big changes in my own sons. Now they value the work that women do. If the woman is not there, well, I’ve seen Amelia’s husband, when she’s gone for the day, I’ve seen him comb and braid his little girl’s hair. I’ve seen him give her a bath and I told him, “That’s good, son, that you appreciate what your wife does, because she does a lot of work.” Their children are very small and she has a big pile of clothes to wash. I’ve also said to my other son, “When will I see you washing the clothes? I see your wife washing clothes all day long.” Even though it’s not all the time, because they have other work to do too, but when they have time, I’ve seen my sons lend their wives a hand.

Amelia: I think it depends on each person’s consciousness. When I didn’t have any position with the organization, it’s as if it was okay to leave all the work to me—the housework, the children. Men didn’t get very involved. But since I began to participate, to leave the house, I’ve seen a change in my husband. I wouldn’t say that he does everything, but even if it’s a little bit, once in a while, he does help me. He helps me with the children. In the morning, he gets them up and dresses them. Sometimes he does their hair, when he has time. Sometimes when we work in the fields together, he’ll say to me, “You know what, let’s work together tomorrow, I need you to lend me a hand in the cornfield,” and then he gets up early to help me with the housework and I go to the fields and help him. We do the work between the two of us. Sometimes he’ll see that I’m upset, for example if I don’t have time to fix lunch for him, or I’m behind on something, and he’ll do it. So I’ve seen a real change. Before, they left all the work to the women, and now it’s different. This change happened a while ago. Ever since I began to participate more, he saw that I couldn’t do everything—take care of the children and the house and also participate in the organization. That’s when he started to change, because he valued my role in the organization. He recognized my rights, and has always supported me in this role.30

One of the strategies presented in the 2001 pamphlet Equality of Rights and Opportunities between Men and Women is that men and women should share the domestic work. “As Zapatista men and women, we have to learn to organize and share the work at home,” reads one section. “Society has taught us that there is ‘men’s work’ and ‘women’s work,’ but that is not true. Men can do the work we call ‘women’s work,’ and women can share ‘men’s work.’ If we learn to do this, we will all have time to participate in meetings, gatherings, and to take on public responsibilities, because domestic work will become the whole family’s concern and not just the woman’s.”31

The EZLN’s orientation is still focused on women’s participation in the movement. Traditional gender roles are being challenged, but in the interest of women participating more actively, rather than evaluating those norms on their own merits. While this approach has its limitations, it has been an effective way to engage men in this dialogue. During the gatherings where this pamphlet was discussed, for example, many conversations noted the relationship between women’s work in the home and their lack of public participation. “If we arrive home at the same time,” one man reflected, “we should do the housework together, for example, prepare the food together. When we’re away from home because of a public responsibility, the woman stays and takes care of the house. So we should do the same for her. When a woman feels liberated from so much work at home, she will begin to accept more public responsibilities. But if she feels overwhelmed by housework, she will not want to take on more work.”32

Men and women within the EZLN have continued to conduct political education, but the messages about women’s rights have changed over time. In the EZLN’s clandestine years, the insurgents carried out much of the organization’s political education and organizing, with women insurgents in particular reaching out to women and promoting women’s rights. While the insurgents’ role in this work has decreased over time, it has not disappeared altogether. In 2003, for example, a small group of insurgents made an appearance at a zonewide women’s gathering in the Morelia region. In a large auditorium, they stood before several hundred women. In their teens and twenties, they were literally and figuratively the sons and daughters of the women sitting before them. Because of their decision to join the Zapatista army, they were treated with great respect and admiration. The group of insurgents began their presentation with music. One of the young men balanced a guitar on his knee and strummed simple chords. For the well-known songs, the women in the audience were asked to sing along. In between each song, an insurgent read aloud a short message about women’s rights—part poetry, part affirmation, part call to action. A young male insurgent read a message acknowledging men’s responsibility to change.

Society’s education taught us to believe that women are worth less, and that, as men, we are worth more. We must recognize that this idea is wrong. . . . In society, in the family, in our communities, and in all other spaces, men have been given more opportunities simply because we are men, and women have been given fewer opportunities just because they are women. . . . No one should be denied their rights because of the belief that some people are worth more than others. We are aware that this will not be easy, for men or women, but the time has come to free ourselves of these ideas and practices that have only caused discrimination and sadness and suffer-ing in women’s lives.

“Women’s work” can also be done by your sons and your husband. Teach them with patience to share your work. That way you will have more time to organize and to go meetings, gatherings, assemblies, or to fulfill other commitments or responsibilities. The time has come for you to dedicate time to other spaces and work that will help you awaken your consciousness and see another way to live. Don’t stay locked up in your kitchen anymore. You have the right to do other things and to do something important for your people and for the struggle.33

A woman insurgent, slightly older than the others, closed the presentation with this message: “It is our job to create the foundation

of this new society. . . . The ideals of our organization are like seeds that we need to plant and make them grow, so we can become new men and women. We don’t want to be Zapatistas in name only. We should being putting these ideas into practice.”34

The importance of women’s participation in the Zapatista movement is still a central message, but these insurgents also conveyed that women’s liberation is important for its own sake, and that men need to change in various ways. Especially when compared to the EZLN’s earlier political education, the difference is notable. Each Zapatista region also carries out its own political education work. Equality of Rights and Opportunities between Men and Women, for example, was produced in the Morelia region. It presents the points of the Women’s Revolutionary Law and discusses how to put those rights into practice. It poses several discussion questions, as seen in a section titled “They say we have the same rights, but what is the reality for women in the family and in the community?” or in the final section of the pamphlet, which asks, “How are we going to make equality between men and women a reality?” The pamphlet states:

The problems of inequality and discrimination are like a very large tree. Its roots are very deep and they are not easy to uproot. The government has humiliated us and discriminated against us, denying us our rights; we understand this well. But what we do not always see is that, without realizing it, we are repeating the government’s oppression against women within our own homes.

We must pull out the bad roots in order to plant the new tree that we want, together, men and women. We must uproot and plant, plant and uproot; leave aside the old life and plant a new life. Only with our own actions and participation will we put our rights into practice . . . Liberation will not fall like a miracle from the sky; we must construct it ourselves. So let’s not wait, let us begin.35

When compared to Compañeras, Participate in the Zapatista Revolutionary Struggle, written by the Zapatista leadership in 1995, the pamphlet Equality of Rights and Opportunities between Men and Women makes it clear just how much the EZLN’s perspective toward gender and women’s empowerment changed in the intervening six years.

The impact of this variety of strategies is evident in a community like Siete de Enero—a village that was built on occupied land after the Zapatista uprising. It was founded by young people, including a number of former insurgents. It is a highly organized and disciplined community, and there has been a remarkable shift in gender roles. Women’s political participation is taken for granted. Men and women seem at ease with each other, joke around together, and married couples are more likely to have a relationship of equals. While there is still a gendered division of labor, Siete de Enero is one of the Zapatista villages where you are more likely to see a man cooking or carrying a young child.

While Zapatista women have already achieved remarkable changes in a relatively short time, some shifts may take a generation to fully implement. “There are many changes we want for our daughters because they’re still small and can learn and understand more,” said Comandanta Micaela, “because sometimes it’s hard for women to get rid of the ideas we already have.”36 Celina described the changes she is working to implement in her own family.

I want to be a good example for our children. If I’m locked up at home, what will happen to my daughters? They’re never going to want to participate. Now that our children attend the autonomous school, they come home every day and tell us what they learned. They want to talk about it at home. At school they learn about women’s rights and that boys can work in the kitchen too. The education promoters bring these ideas back with them from their trainings and teach the children new things. The children get excited and then come home and talk about it.

One day I went to work in the cooperative. When I got home it was late in the day—four o’clock in the afternoon— and my son had already done everything. He made coffee, he built a fire, and he had put the beans on to cook. He said to me, “I thought you would be tired when you got home.” My sons were not like that before. They understand that they should help me, it’s not even necessary for me to tell them. Sometimes they say, “You wash the cornmeal, Mama, and I’ll grind the corn.”

Among my children, the work is equal. When I’m away from home, my children share the work between my daughter and my two older sons. It was not like that before. Before, only girls worked in the kitchen. Sometimes girls didn’t even go to school because they had to stay home and help their mothers. The biggest change in our communities has been with the children. It’s not as easy for our husbands to change, but with our children, we’ve seen how things can truly be different.37

The EZLN has sought to reinforce families raising their children with different ideas about women’s rights, by emphasizing gender equality in the autonomous schools, for example. “With the autonomous education system, we are already seeing the formation of a new generation,” said Beto during a gathering between the EZLN and civil society in 2006. “By now, there are two or three groups of children who have graduated from the autonomous schools and we have already begun to see a difference.”38

Isabel, one of the Zapatista women who pushed for these changes while she was in a position of military leadership, also reflected on this question.

We came to the conclusion that change is not going to come from somewhere else, and it’s not going to fall from the sky. If we want to move forward in terms of having the same rights, we have to think about how we’re raising our children. That’s how these changes that exist in our dreams are going to become a reality.

In the region where I was working, women took on the responsibility of changing the consciousness of their small children within the home, in their lives, and in the environment of the family and the community. But for me, the simplest thing is to put it into practice ourselves. Not just women, men too: because if the father is grinding the corn, the son is not going to protest when it’s time for him to grind the corn. Or if the father washes the clothes, the son is not going to say, “I shouldn’t have to do that because it’s women’s work.” Since he’s seeing his father doing the same things, it will not be difficult for him.39

Throughout the Zapatista movement, women frame their hopes for their collective liberation in terms of the life they envision for their daughters. Guadalupe, the Zapatista woman from Miguel Hidalgo who still receives little help from her own husband, said, “I’m making this effort because, even if I never see it myself, I want my daughters not to suffer the way we suffered, with the landowners for example. They’ll be able to go to school, they’ll know how to read and write. We’ve already lived through what we lived through, but we want our daughters to have the right to an education.”40

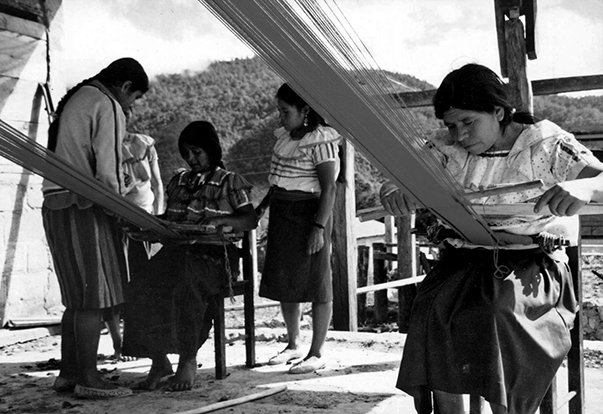

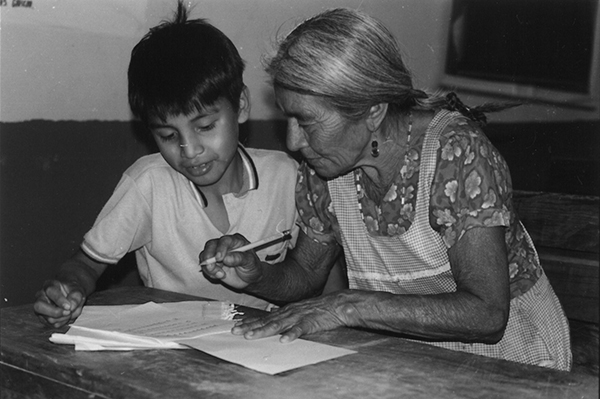

A student in the autonomous municipality Francisco Gomez does his homework assignment—to teach his grandmother how to read. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

Zapatista women have fought tenaciously and have faced immense obstacles along the way. The young women who have grown up in the context of the Zapatista movement manifest the transformations that have taken place in Zapatista territory. Many young women are flourishing in the spaces opened for them by their grandmothers, mothers, aunts, and older sisters.

Comandanta Micaela, for example, has four children—three sons and a daughter. I met Micaela’s daughter, Clara, when she was about nine years old. Shy but playful, she was the youngest of the four. Having grown up in the heart of the Zapatista movement, it is no surprise that she would develop into a leader herself. By the age of sixteen, she had already been chosen as one of the regional women’s coordinators, and all indications pointed to this being just the beginning of a long trajectory. While her brothers are all active in the movement, none of them, interestingly, have taken on this level of leadership.

Débora, one of the women who helped defend her village’s land from Mexican soldiers, has been a driving force for organizing women in her autonomous municipality of Che Guevara, and her ability to motivate and inspire other women has been crucial. She was a women’s regional coordinator for many years before being chosen as a member of the CCRI. A mother of ten, Débora juggles her responsibilities to her family and her commitments to the Zapatista movement. Her oldest daughter, Fabiana, was an education promoter for several years as a teenager, helping to coordinate the large community’s autonomous school, plan the curriculum, and teach the children. She went on to become a news broadcaster for Radio Insurgente, the EZLN’s radio station.

Not only are these young women taking on key roles of responsibility at an extraordinarily young age, but they carry themselves with strength and confidence and they exhibit leadership and maturity. Their romantic relationships with young men are based on a much greater degree of equality, and their communities treat them with a level of respect that their mothers fought for, but could never take for granted. Throughout the Zapatista movement, there are countless mothers like Micaela and Debora, and countless young women like Clara and Fabiana.

“As older women we feel happy,” said Blanca Luz, a Zapatista woman in her fifties. “How could we not be happy when we see these changes, that our granddaughters have freedom in their lives?”41 Eva concurred, giving an example from her own family: “The children, they know. My granddaughter, when she was smaller I used to tell her, ‘Come here, mi hijita, there’s more work to do.’ ‘Ay, so much work, abuelita!’ she would say. ‘I’m a little girl, I should be free. Girls should be able to play.’ That’s what she used to tell me when she was about six. ‘I have rights now, too, abuelita. Don’t give me so much work!’”42

Members of the Zapatista support base wait patiently on their bus to depart the rebel stronghold of La Garrucha and begin the Other Campaign. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)