Doña Rosita, the daughter of indigenous rights advocate Erasto Urbina, has lived her life in her father’s footsteps. She was in her late sixties when I interviewed her in 2009, and she remembered her reaction to the Zapatista uprising vividly. “That day, when I opened my eyes and they told me what happened, I said, ‘This is incredible.’ Of course I saw it as a continuation of a struggle that had never ended, because I know the indigenous peoples have never stopped fighting. But this movement was so perfectly well organized.”1 Referring to her father’s death in 1959, she added, “That part of my life remained in silence until the emergence of the Zapatista movement.” Reflecting on women’s role in the EZLN, she said:

Women have participated in all struggles, you know. Women have always been there. But not as many and not as well trained [as the Zapatista women were]. The day I saw them for the first time, I said, “I can’t believe it!” I saw them in the center of town. It was late and they looked so serene, so tranquil in their struggle, but not nervous, not afraid. They weren’t running away from anything, they were facing it head-on. The truth is, I cried for three days after seeing that, because I could hardly believe it. It was like seeing a dream come true.

Since 1994, the EZLN has engaged in dialogue with national and international civil society, and the exchange between Zapatista and non-Zapatista women has been especially fruitful. The Zapatista movement has influenced grassroots activists and social movements like few other movements of the late twentieth century, and demonstrated a remarkable ability to communicate with outside supporters at a time when the Internet was only just emerging as a mechanism for global communication. The EZLN, knowing that it could not achieve the scale of social change it sought on its own, has made various efforts to coalesce into a broader national and international movement. Each Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle has been a call to other sectors of society or an effort to initiate an organized political force. While not always as successful as it hoped to be in catalyzing new political formations, the Zapatista movement has had a tremendous impact in Mexico and around the world—one that may be difficult to measure but is impossible to deny.

Two decades after the Zapatista uprising, the world grapples with ever-deeper income inequality, and the fissures in global capitalism have produced disasters such as the financial crisis of 2008. Although the Zapatistas do not occupy the place they once did in the popular imagination, the EZLN was one of the first social movements to put neoliberalism in its crosshairs more than twenty years ago, and it helped jumpstart an international antiglobalization movement. The Zapatista project of indigenous autonomy, strengthened by women’s perspectives and leadership, continues to provide a concrete example of grassroots alternatives to global capitalism. Zapatista women are often aware of their role as a powerful protagonist on the world stage, and their struggles have resonated with other women.

Over the years, the EZLN has mobilized many times to press for its political demands and to reach out to civil society. Doña Rosita, who used to run a small, inexpensive hotel in San Cristóbal de las

Casas, recalled her daughter’s interaction with the Zapatistas during one such event.

One day there was going to be a march, when 1,111 Zapatistas were setting off for Mexico City. They gathered here in the zócalo [of San Cristóbal]. I had a lot of work to do in the hotel and I couldn’t go. I wanted to but I couldn’t, but my daughter Elvira went. My daughter had a monthly income of about 20,000 pesos, which was an excellent salary. She worked as a tourist guide. She’s a physically weak person— she had problems with her kidneys—so she had bought some sneakers that cost a thousand pesos to be able to work as a guide. She said to me, “Are the women coming, Mama?” “Yes, they’re coming.”

“Okay, I’m going to go see them.”

When the women arrived, they announced, “So-and-so is going to speak now,” and a young woman got up on the stage. She was a small woman, slender, with no warm clothes on, and it was very cold. [My daughter said,] “I saw her shoes and they were falling apart.” And then she told me, “Mama,

I couldn’t even pay attention to what she was saying because I felt like I was going to start crying. I felt so stupid because I don’t have the courage to live and to struggle like she does, and I needed sneakers that cost a thousand pesos, how awful!

I went running over to the delegation to ask them, ‘Do you want money?’ because I didn’t dare ask the young woman if she wanted my shoes. But they said, ‘No, we’re not accepting money,’ and so then I felt worse and I came home to talk to you because, oh Mama, it’s just not right.”

I think the same thing that happened to Elvira has happened to many, many Mexican women. I have seen it on a national level. Here in the hotel I have had the chance to see many young Mexican women who come to observe the movement. They’re girls who are in school, university students who have it all. They don’t have any reason to sacrifice themselves and to come here, at least not from their parents’ perspective, but they have begun to have a political consciousness. I believe the history of Mexican women is going to change as a result ofall this. It has already changed a great deal.2

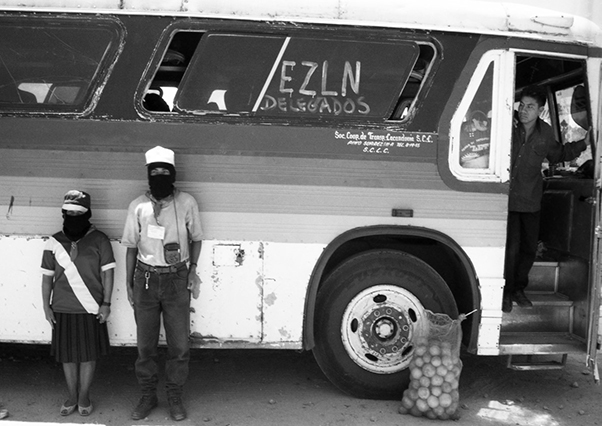

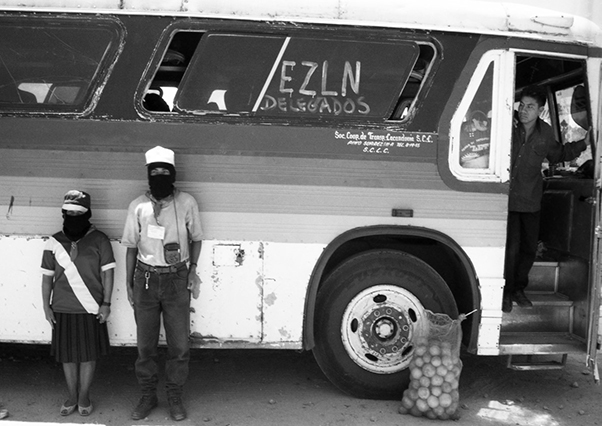

Two of the 1,111 Zapatistas who traveled to Mexico City in 1997 wait to board their bus. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

A Zapatista woman and her young child in the zócalo of Mexico City during the 1997 mobilization. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

Doña Manuela, the Tzeltal elder from La Garrucha who led the charge during Guadalupe Méndez López’s funeral march, was one of the 1,111 Zapatistas present that day. “I went to Mexico City,” she recounted. “Yes, that’s right. I had never been to any city in my whole life but this little old lady went all the way to the capital to tell the damn government what I think of them. ‘Damn government, count us well!’”3 As she recalled that day, Doña Manuela raised her voice and waved her fist in the air as if she were back in the zócalo ofMexico City.

My God, but there were so many people! I went all the way to the National Palace. I don’t remember the names of all the places we went but I know it was far. I like to see new places and listen to other people’s voices and have them listen to mine. I was happy to meet so many people from all over Mexico. My goodness, but how they cried when we left!

The last night there was a dance and I saw so many tears. “Compañeros and compañeras, thank you for coming,” they told us. “We’ve been waiting for you for a long time. Come back soon. Don’t forget that you’re not alone and you’ll never be alone.” It filled my heart with emotion.

The Zapatista movement has made a particular impact on non-Zapatista women—indigenous and mestiza women alike, especially in Chiapas where they live side by side. According to a pamphlet published in 1995 by K’inal Antzetik, a nongovernmental women’s organization in San Cristóbal, “New winds are blowing through the Mexican southeast. Women are making noise in the streets, at rallies, at meetings, in workshops and forums, in the Zapatista army, in civil resistance. The unusual becomes normal, the hidden becomes public, and the individual, collective.”4 Yolanda Castro was a founding director of K’inal Antzetik and has been a key figure in the feminist movement in Chiapas since before the Zapatista uprising.

At the beginning of January 1994, after the EZLN’s uprising, it was a surprise to learn that 30 percent of their military ranks were made up of women. . . . In the indigenous communities, a climate was increasingly created where people demanded more information about their rights. . . . Indigenous women began to analyze their political, economic, social, and cultural rights They discussed the Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law. They expressed that the image of Comandanta Ramona, one of the leaders of the EZLN, motivated many of them to organize. . . . The movements unleashed by the Zapatista insurgency have created a high level of political consciousness among women and, as a consequence, a high degree of cohesion in the organizations to which they belong.5

This consciousness was apparent in a 1994 workshop about women’s rights, where non-Zapatista indigenous women from the highlands region of Chiapas shared their thoughts about Zapatista women. “Our heart is no longer the same and neither is our way of thinking,” said Pascuala, a Tzotzil woman who attended the workshop. “My mother and my grandmother lived their lives in silence. All they knew about were what colors they would embroider for Our Lady of the Rosary. Today, my daughters continue to sleep on a dirt floor. They are hungry and get sick. But the peace we want is different, even if we have to walk very far to achieve it. My heart and my thoughts have changed; they are no longer in silence.”6

Merit Ichin Santiesteban, another founding member of K’inal Antzetik, has worked with artisan cooperatives in the indigenous communities of Chiapas for more than two decades. Several years later, she recalled that same time period and the swirl of excitement that came after the Zapatista uprising. “When [Zapatista women] lifted their voices and let us hear their demands,” she remembered, “many women, groups, and collectives around the country and the world saw themselves reflected in them. Many groups had already been doing this work for years, so when we heard their voices, it was a confirmation that we were on the same path, heading in the same direction. This gave strength to other women who found the courage to speak up and to demand more information about their rights. In those years, there was a lot of work organizing workshops, meetings, and state and national conventions.”7

The Zapatista movement also helped catalyze greater political organization of indigenous women at the national level. When the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) was formed in 1996, Comandanta Ramona’s presence increased its visibility. “Our heart is just one small heart beating among many hearts,” Ramona told the crowd gathered in the zócalo of Mexico City.8 The CNI was one of the organizations to call for a Coordinadora Nacional de Mujeres Indígenas (National Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Women, CNMI). In August 1997, over five hundred women, repre-senting more than a hundred organizations and nineteen indigenous peoples, came together to form the CNMI. Addressing this gathering on behalf of the CNI, Sofia Robles, an indigenous Mixe leader from the state of Oaxaca, noted the EZLN’s influence on the creation ofthis broad coalition ofindigenous women: “Since 1994, with the EZLN’s uprising, many social sectors began to reflect seriously on the situation of inequality in this country. One of these sectors was women. This, of course, has been happening within the EZLN itself, with the Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law, in which they demand equality in all areas. From there, a series of initiatives was unleashed to discuss the problems of indigenous women in academic spaces and within our own organizations.”9

The relationship between the EZLN and women’s advocates from civil society has not always been so smooth. Some feminists and women’s rights organizations, including some of those who embraced the EZLN in 1994, later became disillusioned with what they perceived as a failure to respond to certain gender-based demands. In 1996, for example, a group of women’s rights organizations based in San Cristóbal wrote a letter to the EZLN taking it to task for not responding more proactively to accusations of sexual assault within its ranks. Their criticism was directed primarily at the male leadership of the EZLN, not at Zapatista women in the villages. Subcomandante Marcos critiqued the feminists for their limited comprehension of the reality of poor indigenous women in rural communities, but did not respond directly to their accusations. This relationship improved again over time, with some but not all of these groups and individuals. Mercedes Olivera, a key figure in the women’s rights movement in Chiapas and one of the signatories of the 1996 letter, has since spoken at a number of events convoked by the EZLN. In 2007, Sylvia Marcos, a Mexican feminist and psychoanalyst, called the EZLN “the most encouraging movement for feminists.”10 Speaking at the same event, Subcomandante Marcos acknowledged the initial clash between the EZLN and urban feminists but was hopeful about scholars like Sylvia Marcos, who understand that “Zapatista women, like many women in many corners of the world, transgress the rules without discarding their culture. They rebel as women without ceasing to be indigenous and Zapatistas.”11

Zapatista women took that rebellion beyond their own homes and communities, into the broader Mexican nation and the consciousness of the international community. Over the last twenty years, the Zapatistas have organized street rallies, cultural programs, gatherings, and mass marches—local, national, and international— ranging from meetings in their own villages to mobilizations of hundreds of thousands of people in Mexico City. Here are a few key examples, by no means an exhaustive list, of the efforts of Zapatista women to connect with others around the world and to build a broader movement for justice and dignity.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, pundits declared the definitive triumph of free market capitalism. As the Cold War drew to a close, communism no longer represented a model for liberation movements as it had in the past. So when the EZLN marched into the global spotlight in 1994, it gave hope to a generation of social justice advocates by providing an example of what a new wave of popular movements might look like. In 1996, the EZLN held the Primer Encuentro Intercontinental por la Humanidad y contra el Neoliberalismo (First Intercontinental Gathering for Humanity and against Neoliberalism), inviting all those who had been negatively impacted by global capitalism to come together to share ideas and form alliances. Almost five thousand people from more than forty countries attended.

The EZLN hosted the Intercontinental Gathering in the five Aguascalientes, one in each of the five regions of Zapatista territory. In the mud and in the baking sun, and sometimes late into the night, participants sat outside in thousands of folding chairs to listen to the proceedings. Major Ana María gave the opening speech in Oventic. In her black ski mask and military uniform, and with a worn red bandanna tied around her neck, she spoke into the microphone in a quiet but powerful voice.

Brothers and sisters of Asia, Africa, Oceania, Europe, and America, welcome to the mountains of the Mexican south-east. Let us introduce ourselves. We are the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. For ten years, we lived in these mountains, preparing to fight a war. In these mountains, we built an army. Below, in the cities and plantations, we did not exist. Our lives were worth less than those of machines or animals. We were like stones, like weeds in the road. We were silenced. We were faceless. We were nameless. We had no future. We did not exist. For the powers that be, known internationally by the term “neoliberalism,” we did not count. We did not produce, we did not buy, we did not sell. We were a useless figure in big capital’s accounts. Then we went to the mountains to find ourselves and see if we could ease the pain of being forgotten like stones and weeds . . .

Behind our black mask.

Behind our armed voice.

Behind our unnamable name.

Behind what you see of us.

Behind this, we are you.

Behind this, we are the same simple and ordinary men and women that are repeated in all races, painted in all colors, speak in all languages, and live in all places . . .

Today, thousands of human beings from all five continents shout, “Enough is enough!” here, in the mountains of the Mexican southeast. They shout “enough!” of conformism, of doing nothing, of cynicism, of selfishness, which has become the modern god.

Today, thousands of small worlds from all five continents are putting an ideal into practice here, in the mountains of the Mexican southeast, the beginning of the construction of a new and good world, in other words, a world where all worlds fit.12

“A world where many worlds fit” would become one ofthe Zapatistas’ most popular and well-known slogans. The Intercontinental Gathering captured the spirit of a particular moment in time and helped plant the seeds of the antiglobalization movement.

The Zapatista movement has had a deep political, social, and cultural influence at the national level as well. In March 1999, the EZLN organized the Consulta Nacional, a national referendum that asked Mexican society to voice its opinion about indigenous rights and the militarization of Chiapas. Five thousand Zapatistas traveled in pairs throughout Mexico to dialogue with civil society and then hold the referendum. Elsa, a Zapatista woman from the autonomous municipality Che Guevara, was a teenager in 1999. She went to the Mexican state of Guerrero to participate in the Consulta and had this to say:

We went to talk about indigenous rights and culture, and also about women’s rights. We held rallies and marches. People asked us many questions and sometimes the press was there too. We asked people from every state to support us during the Consulta Nacional because on March 21 they were going to vote on [the referendum]. I felt happy and content. When we left, we said good-bye to our brothers and sisters in the state of Guerrero. They told us, “Compañeros, we don’t want you to give up your struggle because your struggle is our struggle too and it belongs to all ofMexico.” They also told us, “You’re not alone; we’re here with you.” It was hard because there were times when we were hungry and thirsty and we had to wear ski masks the whole time.

But I feel like my life is different now because it was the first time I went anywhere like that. Before that, I had been to San Cristóbal, but I had never been to another state.13

For the EZLN, the Consulta was also an opportunity to train a new generation of leaders. Before leaving Chiapas, the five thousand Zapatista delegates participated in intensive political education and training to prepare for public speaking engagements and meetings. On the eve oftheir departure, they gathered in the five Aguascalientes. In Morelia, Zapatista trucks arrived, dropped people off, left, and came back a few hours later with another truckload full of people, again and again. There was electricity in the air: excitement about the mobilization, nervousness about what they would say to large crowds of people who wanted to know all about the EZLN, and some trepidation about how the government might respond.

An exercise in radical participatory democracy, the Consulta was also carried out with an element of blind faith. Throughout Mexico, civil society organized regional and statewide coordinating committees to receive the visiting Zapatistas, and the EZLN committed to going anywhere someone would host them. Yolanda Castro, the cofounder of K’inal Antzetik, was also a member of the coordinating committee in the highlands region of Chiapas. “Practically the entire Consulta was carried out by women,” she said, “the promotion, the outreach, and the coordination. It’s a space that women have given life to, and so it’s principally women’s strength and women’s ideas that we see in the coordinating committees: women teachers, students, and professionals working in nongovernmental organizations, women from different neighborhoods and communities.”14

Events during the week leading up to the referendum included a meeting at the border fence between activists from Mexico and the United States; a soccer match between Zapatistas and former professional soccer players in Mexico City; and rallies, talks, and press conferences held all over the country. On March 21, the Zapatistas carried out their national referendum, which asked about indigenous rights, implementation of the San Andrés Accords, the demilitarization of Chiapas, and democratic transformation in Mexico. Approximately three million Mexicans voted in the referendum, with 95 percent responding “yes” to all four questions.

After the Zapatistas returned to their communities, I interviewed Ernestina, Silvia, and Margarita, all from the village of Morelia. We gathered in the community’s collective kitchen, where they told me about their experiences during the Consulta. Ernestina, who was forty-five at the time, had traveled to Querétaro. “Some people asked us why we had gone all the way to the state of Querétaro and what we wanted,” she said. “We answered, ‘We want peace. That’s why we’re here, because the government signed a peace agreement on February 16, 1996. But they haven’t complied with even one point ofwhat they signed. I think the government wants more war. I don’t know, but they won’t comply with the agreement they signed.’ That’s how we responded to their questions.”15

Silvia and Margarita had both gone to Michoacán. Silvia, who was twenty-eight at the time, said:

We went all over Mexico to find other compañeros and during the Consulta we realized how many people need the EZLN. Because what the EZLN is fighting for—people all over Mexico are fighting for those same things. People told us about all their problems, how exploited they are, and how the government doesn’t listen to them. They’re living in the same kind of poverty we are. That’s why the Consulta was so important, because we came back with more clarity and they have more clarity too. We have a lot of support out there. There were so many people! They chanted “E-Z-L-N!” and other slogans too. So I think it was a step forward for the EZLN.

In addition to the referendum, the Zapatistas used face-to-face encounters with different sectors of the Mexican population to counter government propaganda against them. Ernestina recounted: “People told us, ‘We’re so glad you’re here because we see a lot of things on television. They say the Zapatista movement is dead, that there are no more Zapatistas left, and we thought it was all true. But here you are in person and we’re interested in what you have to say.’”

The Zapatista women were often most touched by down-to-earth conversations with regular people. “We had a meeting with schoolchildren who asked us a lot of questions,” recalled Margarita, who was twenty-seven at the time. “They asked us about the children in Chiapas. We told them that children don’t have good schools or health care. We told them that many children are malnourished because they don’t have a good diet and sometimes it’s hard for them to learn in school because they’re hungry. They felt sad about the children in Chiapas.” One of their favorite stories was about when two Zapatista women from different generations met. One of the women, from Chiapas, was active in the current Zapatista movement and the other, from Michoacán, had been involved with the original Zapatistas—the followers of General Emiliano Zapata—during the Mexican Revolution. They exchanged their shoes as a way to remember each other.

Of the five thousand Zapatistas who participated in the Consulta, 2,500 were women and 2,500 were men, the idea being that one man and one woman would travel in pairs to each ofMexico’s 2,500 municipalities. “What people asked us about the most was why women were participating in the Consulta too, and not just men,” said Silvia. “I told them it’s because, in Zapatista communities, women have the same rights as men.” The women, however, were also honest about the reality of their daily lives. “On the radio they asked us what life is like for women in Chiapas,” recalled Margarita. “We said it’s very difficult because, as indigenous women, we’re responsible for all the work in our homes. That’s how we responded because our lives are still very hard.”

The political training beforehand and the experience of participating in the Consulta gave the thousands of Zapatista women who traveled to every corner of Mexico increased confidence and other leadership skills to continue participating more fully. Silvia recounted:

As soon as they told me I was going to participate in the Consulta, they started telling me, “Compañera, you’re going to have to speak up. Ifyou speak up, the women there will feel encouraged because there will be compañeras there too, you know.” I felt proud of myself when I responded to some of the questions. When I didn’t know how to answer one of the questions, I would ask the compañero who was there with me, and we both helped each other that way. I liked participating and that’s when I realized that it’s true that women have strength.

In Chiapas, the coordinating committees that were set up to carry out the Consulta in 1999 continued to organize with different sectors of the population even after it was over. The following year, these committees worked together with the EZLN to celebrate International Women’s Day with a large women’s march. The march was organized as a joint effort between Zapatista women and women of Mexican civil society—the first event of its kind and a manifestation of the close relationship between Zapatista and non-Zapatista women that began in 1994.

On the afternoon of March 7, 2000—the eve of the International Women’s Day march—truckloads of women began to arrive in San Cristóbal from all over Chiapas. Zapatista women came from the five Aguascalientes. Women from civil society came from five additional regions of Chiapas. Early on the morning of March 8, more than eight thousand women gathered on the outskirts of San Cristóbal and then marched through the streets toward the center of town. The Zapatista women marched first—faces covered by ski masks, some with babies in their arms, some carrying handwritten signs. One sign read, “I like when you give me hugs, I like when you give me kisses, but most of all, I like when you do the dishes.” A smaller group of non-Zapatista women marched behind them. While the Zapatista women were all from rural, indigenous communities, the non-Zapatista women were a more diverse group: indigenous and mestiza, urban and rural, poor and middle class.

It was a typical women’s march in its demands to respect women’s rights and equality. It was a typical Zapatista march in its demands to demilitarize Chiapas and comply with the San Andrés Accords. What was unique was the combination of the two. A contingent of two hundred people took over a government radio station and broadcast for an hour. The pronouncement was read by a Tzeltal Zapatista woman: “We demand that the government withdraw all the soldiers it has stationed in Chiapas. We are not making our demands with arms. This is a peaceful protest . . . Many of us don’t know how to read or write—that’s why we came here to be listened to. We want you to know that we are not used to the presence of soldiers.”16 The radio broadcast also denounced violations ofwomen’s human rights by soldiers, police forces, and paramilitary groups. Protesters in the street used handheld radios to listen to the broadcast, which ended with the call, “¡Vivan las mujeres zapatistas!” (Long live Zapatista women!).

Zapatista women flood the streets of San Cristóbal de las Casas on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2000, to demand respect for indigenous women’s rights.

A banner at the Women’s Day march in 2000 demands implementation of the San Andrés Accords and the withdrawal of the Mexican army from indigenous communities. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

Zapatista women at the rally that concluded the Women’s Day march, in San Cristóbal de las Casas’s central plaza. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)

Gloria, a young Tzeltal woman from the Zapatista community Diez de Abril, attended the march that year. “I was very impressed,” she said. “I felt happy because it was a women’s march and I thought it was really beautiful.”17 The march strengthened the bond that already existed between Zapatista and non-Zapatista women. “I really like that we marched together with women from civil society,” Gloria added. “I realized how many of them were marching with us. In the past it hasn’t been like that. It was very encouraging to have them accompanying us. Now we know they are our compañeras and we are more united.” As a member of the coordinating committee in the highlands region, Yolanda Castro helped organize the march. According to her:

This march was very, very important, and different from any other Zapatista march because the women from civil society played an important role. I see it as a historic event. The participation of women in civil society has always been something separate, and now other women have really taken on the struggle of the Zapatista women. I think this is a first step, having organized this march together. The image of the rally is still clear in my mind: women with their faces covered and women without ski masks on, but in the end it’s the same struggle. And to see ourselves together was to recognize the potential that we have as women.18

The International Women’s Day march also provided an opportunity for Zapatista and non-Zapatista women to learn from each other. Gabriela Mendoza Carillo, another member of the coordinating committee, shared her perspective.

Marching together generates greater consciousness on the part of the compañeras of civil society because the Zapatista compañeras have an obvious level of discipline: for example, the way the march itself was organized. The Zapatista women marched in lines, in four columns, whereas we marched in a big disorganized group, and you could really see the difference. The march had an impact, a powerful impact, because we saw women carrying their babies, and older women, and we were left with that idea of what it means for those women to be participating in their struggle.

This march was also important because the problem we often see as women in civil society is that our partners support the Zapatista struggle and they’re in favor of women’s rights, but in reality it’s not like that. They continue beating their wives, they continue treating them the same way they’ve always treated them. So for us it has meant a profound questioning because what Zapatista women are doing sets an example. It helps us to be stronger, and not depend so much on men.19

Just a few months after the women’s march, in July 2000, the PRI lost the presidential elections after more than seventy years in power. It began to look like a propitious moment for the Zapatistas. The new president, Vicente Fox of the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party, PAN), had famously promised in his campaign to resolve the conflict in Chiapas in fifteen minutes. The EZLN announced three conditions to reinitiate the peace process, which had been stalled for several years: the closure of seven Mexican army bases, all near rebel-held territory in Chiapas; the release of all Zapatista political prisoners; and the passage of a law on indigenous rights and culture that would represent the implementation of the San Andrés Accords.

To pressure the Mexican government to meet these demands, the EZLN organized the Marcha de la Dignidad Indígena (March for Indigenous Dignity). Subcomandante Marcos and twenty-three Zapatista comandantes traveled to Mexico City, making numerous stops along the way, including at Nurio, Michoacán, for the third National Indigenous Congress. The Zapatista caravan, led by a bus draped in the Zapatista and Mexican flags, grew in size as it wound its way through Mexico. The central plazas of big cities and small towns filled to overflowing with people wanting to see and hear the Zapatistas. Crowds lined the streets as the Zapatista caravan passed by. People waved flags and banners, and reached out their hands to brush fingertips with the Zapatistas, who leaned out of the bus windows to share this fleeting human contact. Señoras cooked massive pots of food for those traveling with the caravan. On March 11, 2001, more than a quarter-million people filled the massive zócalo in Mexico City to welcome the Zapatistas to the nation’s capital. This outpouring of political support was also an emotional manifestation of what the Zapatista movement had meant to many Mexicans since 1994: hope for people who, for a long time, had nothing to feel hopeful about; and dignity for the poor, the marginalized, and everyone who heard an echo of their own experiences when the Zapatistas dubbed themselves “the voice of the voiceless.”

On March 28, Comandanta Ester spoke before the Mexican Congress, along with Comandantes David, Zebedeo, and Tacho. It was the first time an indigenous woman had ever addressed the Mexican Congress, and the most oft-repeated lines from her speech reflect the historic nature of this occasion: “My name is Ester, but that is not important now. I am a Zapatista, but that is not important now either. I am indigenous and I am a woman—that is all that matters right now.” In her speech to Congress, Ester appealed to the legislators to pass a law to implement the San Andrés Accords.

There are those who say this proposal will balkanize our country, but they forget that this country is already divided.One Mexico produces wealth, while another Mexico appropriates that wealth, and yet another Mexico has to reach out its hand, begging for charity. . . . There are those who say this proposal will create Indian reservations, but they forget that indigenous people already live separated from other Mexicans and that we are at risk of extinction. They say this law will promote a backward legal system, but they forget that the current laws promote confrontation, punish the poor, give impunity to the rich, condemn the color of our skin, and make our language a crime . . . We are certain you know the difference between justice and charity, and that you have been able to recognize, in our difference, the equality which, as human beings and as Mexicans, we share with you and with all the people of Mexico.20

Her speech to Congress made Comandanta Ester famous overnight. Back in Chiapas, murals ofEster began to appear throughout Zapatista territory where murals ofMarcos, Che Guevara, and Emiliano Zapata had been ubiquitous before. Women in the Zapatista communities felt an enormous sense of pride in Comandanta Ester, perhaps even more so because she was a political rather than a military leader. Like the other comandantes, she lives in a rural indigenous village alongside the rest of the Zapatista support base, and she wears the embroidered blouse, white shawl, and woven skirt of Huixtán—a Tzotzil region just east of San Cristóbal. “She’s one of us,” women in Zapatista villages would turn to each other and say, “and there she is, speaking before Congress!”

In March 2001, a quarter-million people filled the zócalo of Mexico City to show their support for the EZLN. (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)

The EZLN’s conditions to return to the negotiating table, however, were not met to the Zapatistas’ satisfaction and peace negotiations remained suspended. President Fox would favor social and economic tactics over direct military force to pressure the Zapatistas, but it would soon become clear that throughout his six-year term, he would be just as determined to undermine the EZLN as previous administrations had been.

The EZLN’s last national mobilization to date was La Otra Campaña (the Other Campaign), parallel to the presidential campaign of 2005 and 2006. Declaring the need for another kind of politics “from below and to the Left,” Subcomandante Marcos, and later other representatives of the EZLN, traveled throughout Mexico. Maite Valladolid, a young Chicana photographer who joined the caravan of journalists and solidarity activists that accompanied the Other Campaign, said, “I remember the very first meeting I attended. It was in Tonalá, Chiapas, and it was in an old movie theater. I was sitting there sweating, but I was so impressed with the dynamics of the meeting because Subcomandante Marcos just sat there, listening, while people shared their stories, talking for hours. We went to other meetings where there were no chairs, no tables, and we all stood around in a circle, under a roof made out of sticks and straw. Listening to these meetings I realized that all people really wanted was to be heard.”21

A mural in the autonomous municipality Lucio Cabañas depicts Comandanta Ester and her words to the Mexican Congress in March 2001. (Photograph by Tim Russo.)

This dialogue between the EZLN and civil society, and between Zapatista and non-Zapatista women in particular, was the central theme of the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering in December 2007. Several hundred Zapatista women from all five Zapatista regions arrived in La Garrucha to meet with thousands of women who had come to hear their stories at the Tercer Encuentro de los Pueblos Zapatistas con los Pueblos del Mundo “La Comandanta Ramona y las Zapatistas” (Third Gathering between the Zapatista People and Peoples of the World “Comandanta Ramona and the Zapatistas”). It was the third in a series of gatherings organized by the EZLN, but the first to focus specifically on women’s issues. The village of La Garrucha overflowed with people during the event. Almost every member of the community had people sleeping on the floor, tents set up in the patio, and hammocks hung from any available posts. Many families set up stands to sell food, and the whole community took on a festive air.

A Zapatista comandanta addresses a crowd in La Garrucha during the Other Campaign. (Photograph by Jutta Meier-Wiedenbach.)

Zapatista women share their experiences during the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering. (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)

A Zapatista woman films the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering. (Photograph by Paco Vazquez.)

For three days, women from different parts of Mexico and the world sat on rows of handmade wooden benches, listening. At the beginning of each two-hour plenary, the Zapatista women walked single file into the auditorium. They spoke about a series of topics, creating an overall narrative of what women’s lives were like before the uprising, the changes they had seen, and how women had organized and participated in the Zapatista movement.

This women’s gathering demonstrated that—by 2007—there was a much greater presence ofwomen in the EZLN’s leadership, and women were active at every level of the movement. There were dozens ofwomen comandantas present at the gathering, hundreds of women local and regional authorities, women members of the autonomous government, and women health and education promoters from throughout Zapatista territory. The gathering also reflected a shift in the Zapatista movement’s underlying approach to women’s participation. Greater attention was being paid to gender-based demands, and women’s liberation had become a goal in itself. Women were considered active subjects at the center of their own story, rather than contributors to the story of the Zapatista movement. Patriarchy was acknowledged as its own system of oppression, even as women’s struggle for freedom and overall well-being continued to be intricately connected to all the other demands of the Zapatista movement. The EZLN is not alone in having gone through this transformation. During the women’s gathering, I spoke to a member ofthe Via Campesina delegation, a Brazilian woman representing the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Workers’ Movement, MST). She nodded thoughtfully and said in Portuguese, “Yes, it’s the same process the MST went through.”

Some of the ongoing challenges were evident at the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering, but the power of recognizing and confronting these difficulties was clear too. For example, women in the highlands region of Oventic have had more limited public participation than in some other regions, and during the gathering they painted a complex and realistic picture. Describing the machismo that women still face in their own families, one of them said, “When a woman gets married is when the problem begins, because most husbands still don’t want their wives to participate.”22 They did not hide the sadness in their voices as they described women who never get involved in their communities because “they can’t get rid of the ideas they were taught since they were little.” And at one point they said, “We didn’t bring any women ejido commissioners or community police officers to this gathering. We couldn’t, because there aren’t any.” This simple statement felt like a confession, a desire to acknowledge how much work there still is to be done. Their sincerity allowed outsiders a real glimpse—a window into their day-to-day struggle to exercise the rights they know they have but are often still denied. “We are not going to let women continue to live the same way our parents and grandparents did,” concluded the women from Oventic.

Perhaps this acknowledgment of the remaining challenges was precisely what was so inspiring to outsiders, both men and women. Understanding the obstacles Zapatista women have faced made their achievements that much more meaningful and their determination that much more compelling. Regardless of the reason, the gathering seemed to give the Zapatista movement, as well as its supporters, an injection of energy and enthusiasm. During the closing ceremony, one man from civil society told me, “This is the most excited I have felt about the Zapatista movement in a long time.”

In the same spirit as other Zapatista gatherings, this event brought people together to listen to each other. “Brothers and sisters from Mexico and the world,” said Everilda, an alternate member of the CCRI from La Realidad, “we are telling you our stories as Zapatista women. But it’s not because we want you to feel sorry for us. It’s so you can learn from us and we can learn from you.”23

Interspersed with the Zapatista women’s presentations, women from a wide range of ages, cultures, and political backgrounds shared their experiences as well. Gloria Arenas Agis, a Mexican political prisoner, wrote a letter that was read aloud during the gathering. “The uprising on January 1, 1994, touched the world,” she wrote, “and there you were, the women. The EZLN shook up the concept of rebel organizations and there you were, with Comandanta Ramona and the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Zapatista communities, the autonomous municipalities, and the Caracoles are an example of people’s power in Mexico and the world, and there you are.” She went on to say that her “Zapatista sisters” are part of a struggle that “gives us light and hope in these dark and painful times. You are teachers for us all.”24

A Brazilian woman representing Via Campesina and the Marcha Mundial de Mujeres (World March of Women) expressed how happy they were to be at the event. “Its international character,” she said, “and the openness with which the compañeras have shared their experiences, allow for the globalization ofwomen’s struggles around the world. At this gathering, we have learned from the political experiences of Zapatista women, their many advances, but that there is also still a long way to go. Their example strengthens our conviction that it is possible to construct a world of equality and justice.”25

The Zapatista women had words of encouragement too. Several comandantas at the women’s gathering had traveled throughout Mexico during the Other Campaign. “We live in different circumstances,” said Miriam, a comandanta from the Morelia region. “We are indigenous people who live in the jungle and you live in cities. There are differences, but we have the same enemy.”26 Dalia, a comandanta from the Garrucha region, first spoke directly to the women she had met during the Other Campaign. “We know you suffer the same things we do,” she said, “because we have gone personally to visit you where you live, to your homes and your neighborhoods. You told us the pain you feel as women and there’s no difference between your suffering and our own.” Then, addressing a broader audience, she added, “Compañeras, we need to organize. In your own neighborhoods, your own regions, wherever you are, organize. We cannot abandon each other, because we are the majority in all ofMexico and the world.”27

For Zapatista and non-Zapatista women alike, the most dramatic advances in women’s rights are often witnessed in the lives ofindi- viduals. Zapatista women have transformed themselves and their communities around them, and have inspired other women around the world to do the same. In a letter to Zapatista women written in 2003, Concepción Avendaño described their impact on her life. Known to her friends as Conchita, she is the daughter of longtime San Cristóbal activists Amado Avendaño Figueroa and Concepción Villafuerte Blanco, who published the newspaper El Tiempo, where the EZLN’s first communiqués appeared. Amado Avendaño ran for governor of Chiapas in 1994 and was considered the “governor in rebellion” by the Zapatistas. Conchita wrote the following letter to express her gratitude to Zapatista women, and gave me permission to reprint it here. Her story begins in December 1993, just days before the Zapatista uprising.

At that time, I was a new mother. My son had just turned one on December 12 [1993] and my son’s father was very violent with me. I was in an oppressive relationship. In Cintalapa, the town where we lived, it was assumed that women were less than men. Conversations with other young women my age were about food: “What are you going to cook today?” At first it surprised me, and then I was bored. Was that really what was so important to them? Didn’t they have anything else to talk about? Just their husband and the house . . .

My husband was very violent. When I met him I didn’t know that. In San Cristóbal, he had given me the freedom I was accustomed to. But once we arrived in that town, he was all over me. I had to ask his permission to go anywhere and I had to put up with his mistreatment and beatings. The women around me accepted this. I felt more and more discouraged and finally began to believe that this is what the world was like, that the world I had known before did not really exist, that this is just how life was. My mother-in-law repeated to me again and again, “This is your cross to bear, daughter. Carry it with resignation.” She would tell me the story of Saint Rita who had a husband worse than mine.28

But on December 12, I couldn’t stand it anymore. He hit me again and I didn’t want that life for my son, so I decided to leave my house and I went back to my parents’ home. He followed me on December 21 and asked for forgiveness. He was a photographer, so he had come to work on two weddings and stayed the whole month of December. On December 31, we were in my parents’ home when the news broke. I didn’t understand what was happening, but I saw these small women, poorly dressed and poorly armed, malnourished, but with a determination that touched my soul. I felt ashamed of myself. How, if I had more opportunities than them my whole life, had I let myself reach this level of oppression, while they, with so many paths closed to them, were willing to die to liberate themselves, and not just from a husband, but from the entire government?!

Since [my husband] was a photographer, he started taking pictures of the Zapatistas. They were published all over the world and I saw those photos in my house every day. I sent one of them to be framed and I hung it in the living room of my house. It was of a woman with her back to the camera, and below her ski mask all you could see was her braid. I felt accompanied. They gave me back what I had lost in Cintalapa. Life did not have to be like this, and I had to free myself.

From then on, I began to study. It took me two years to free myself completely from that man. When he began to see my self-confidence, he attacked me more and more until I escaped. He even took my son away from me and kept him for fifty-four days. He left me in the street, literally homeless, and he beat me wherever he found me. But I freed myself. I rescued my child and now I am happy and strong. I see him in the street and I feel enormous, because I have something that the Zapatista women taught me: dignity.

I thank them for giving me back my dignity, because they also gave me back my self. I don’t have any way to repay them, but if it means anything to them to know, I would like to tell them thank you, because throughout civil society there are surely many, many of us who, thanks to them, have recuperated the most valuable thing, our dignity. May God bless them always, and may there always be light on their path so they may illuminate the way, with their small, strong, brave steps, for those of us who are blind.

Zapatista women have a vision that extends far beyond their own communities. At the end of an interview with several Zapatista women in Morelia, I asked if they wanted to add anything. “I want to tell women around the world: ‘Don’t stop organizing, don’t stop fighting, keep moving forward,’” said Elida.29 They all nodded, reflecting on the changes they had fought so hard to realize and expressing their desire to share this with other women. Comandanta Micaela leaned forward and said: “To all the other women who want to struggle, we want to tell you: ‘We’re with you.’”