The story of the Zapatista movement did not end with the Comandanta Ramona Women’s Gathering. Although two decades of low-intensity conflict have taken a toll on Zapatista communities, the EZLN continues to hold significant territory in Chiapas. It has turned away from trying to change an intractable government and has concentrated more on its own project of indigenous autonomy, which continues to thrive.

A generation of young Zapatistas, born after the 1994 uprising, represents the promise of a revolution begun more than twenty years ago. And though the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, altered the geopolitical landscape, and the “War on Terror” has pulled international attention away from popular social movements like the EZLN, the Zapatistas have not disappeared from the scene. Large mobilizations and gatherings in recent years have demonstrated the movement’s resiliency. In December 2012, for example, coinciding with the end of one epoch in the Mayan calendar and the beginning of another, the EZLN organized a massive silent march in cities throughout Chiapas. Young Zapatistas swelled the ranks of this march into the tens of thousands. In 2013, to mark thirty years since its founding, twenty years since its uprising, and ten years since the birth of the Caracoles, the EZLN invited civil society to attend Escuelitas Zapatistas (Little Zapatista Schools). Thousands of Mexican and international supporters responded to the call and traveled to Chiapas to learn from the Zapatista experience. The attendees included young, urban Mexicans looking to the Zapatistas, once again, as a source of hope and inspiration. The EZLN continues to have global resonance, directly and indirectly informing the political outlook and strategic orientation of many young anticapitalist activists today.

The Zapatista movement has also planted seeds around the world because people like me—and many, many others—spent time in Chiapas and took zapatismo back home with them. As I prepared to leave Mexico in 2003, I had a series of emotional goodbyes with women whom I had come to consider members of my family. Amid the sadness of farewells, I told each of them that I was leaving because I felt a sense of responsibility to return to my own home, my own context, and to continue to do the same work there. Almost every one of them responded, “That’s exactly what we want.”

The Zapatista movement in general, and Zapatista women in particular, have influenced all the activist projects and organizing work I have been involved with since I moved back to the United States— from an environmental justice project with Latina women in San Jose, California, to coordinating multilingual infrastructure for the US Social Forum; from a political education collective in Oakland to a membership organization working with the low-income immigrant community in New York. The Zapatista movement is present in the way I think about long-term movement building, holistic solutions, and the centrality of leadership development; about the intertwined relationship between family, community, and political struggle; about the cyclical nature of life; about developing grassroots institutions to respond to your community’s needs, even as you build collective power to confront institutionalized injustice; and about the fact that none of us have all the answers, that we make the road by walking.

Working side by side with Zapatista women for several years— witnessing and absorbing the quiet dignity of their resistance, their epilogue = 289 unflinching commitment, their unquestioned assumption that the collective well-being takes priority over the individual, and their combination of discipline and humor, militancy and tenderness— influenced me in ways that remain deeply ingrained ten years later. One of the many lessons I learned from Zapatista women was the enduring nature of this work and the patience that comes along with it. Eva, the elder from Miguel Hidalgo whose five adult sons urged her to join the EZLN and whose granddaughter now scolds Eva for giving her too much work, once told me, “The path of this struggle is long and there is still much we want to accomplish. We don’t know how long it will take. There are many things we will probably not achieve ourselves. It will be up to our grandchildren, our great-grandchildren, and our great-great-grandchildren.”1

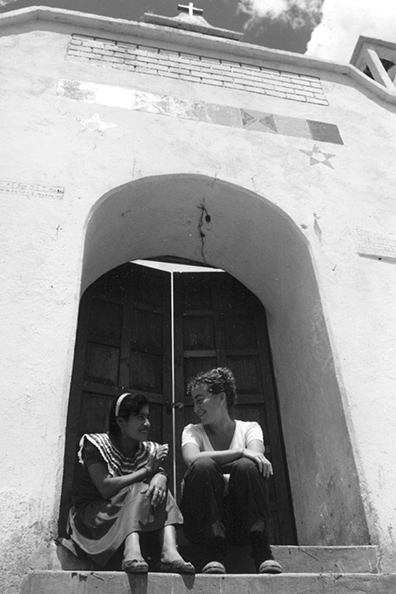

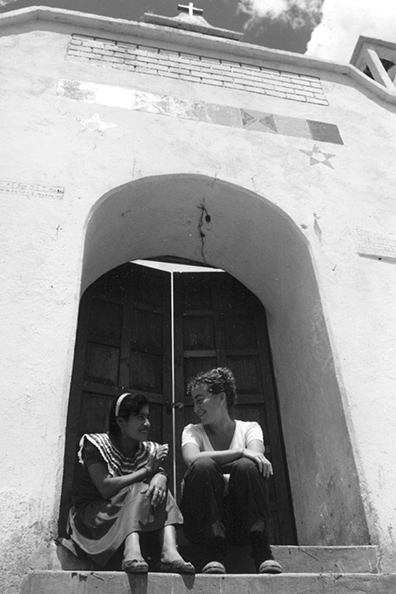

The author with a Zapatista woman in the village of Prado. (Photograph by Mariana Mora.)