Commonwealth of Australia navy: ‘a nondescript force of inadequately trained naval volunteers … absolutely ineffective in war.’

The Times (London) 1904

The beliefs and forces which moulded the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) established the parameters under which the men of AE1 served, and dissensions over costs and control, as well as poor management skills, were complicit in their submarine’s disappearance and their deaths. The genesis of the RAN was not easy and while naval authorities and governments on both sides of the world blustered, volunteers who simply wished to serve struggled to find their way.

During 1859 impetus from the Crimean War caused the British Admiralty to establish an Australian squadron of imperial warships and adopt Sydney’s Garden Island as base for its Australia Station. The lack of colonial confidence in the sea defence provided by the Royal Navy (RN) resulted in five small separate naval forces dotted around the Australian coastline. Although the Admiralty did not believe the dominions were in danger from any foreign power, to discourage any separation philosophies it decided the colonials ‘should be humoured in their desire for a stronger local Navy’.1 The Colonial Naval Defence Act of 1865 granted the colonies subsidies for the manufacture of warships in Britain. Two colonial vessels built under the scheme were Her Majesty’s Victorian Ship (HMVS) 3,390 ton armoured (breastwork) monitor Cerberus2 and the 920 ton South Australian Her Majesty’s Colonial Ship (HMCS) flat-iron gunboat Protector. Both warships were founding ships of the Commonwealth Naval Force (CNF). Protector was eventually deployed by the RAN as the parent/depot ship for Australia’s first submarines, AE1 and AE2, during the New Guinea campaign of World War I (WWI).

The 1865 Act provided for RN officers to be loaned to the colonial navies, whilst sailors were commonly merchant seamen enlisted in a naval reserve. The lack of control over colonial naval forces was nonetheless of concern within the Admiralty which ‘regarded these colonial naval forces with disdain’ and was very reluctant to forge links between them and the RN.3 But by 1870 the Australian Squadron was obsolete and the British Government sought to encourage colonial naval expansion as a means of easing its own financial burden. It was also seen as a means of reducing the number of officers serving in the RN and an incentive scheme saw many transfer. One of these was William Rooke Creswell. Born in Gibraltar in 1852, Creswell joined the RN training ship Britannia as a 13-year-old cadet. Disappointed at the slowness and uncertainty of his promotion within the RN, Creswell retired in 1878 and migrated to Australia with his brother Charles, intent on pioneering the outback. But the harshness of the dry interior of his adopted land did not appeal and he accepted an appointment with the South Australian naval force in 1885 as First Lieutenant of the gunboat Protector. Within five years he had married Adelaide Elizabeth Stow, assumed command of the South Australian colonial naval force and been promoted to Captain.

As the 19th century progressed, the lack of agreement between the colonial authorities and the British Admiralty over cost, control and differing strategic concerns deepened. Unlike many of his RN contemporaries Creswell argued against a naval defence based on dependency, reasoning that subsidy money could be put to better use in the development of an Australian navy rather than to the advantage of the British Treasury.4 He was adamant that Australians should be recruited and trained to effectively man warships deployed by the RN east of the Suez Canal. This brought him in direct disagreement with the Flag Officer of the Australia Station, Rear Admiral Sir George Tryon, RN. In 1886 Admiral Tryon submitted to the Admiralty and the British Colonial Office plans for an Australian Auxiliary Squadron. The Tryon Plan would lay the foundations for the RAN but opposition for the proposal reverberated throughout the Australian colonies because it sought to have the colonies defray the cost of deploying RN ships in their regional waters and incorporating colonial warships into an imperial fleet.5 At the Colonial Conference in London the following year the Admiralty agreed to augment the Australian Squadron with two torpedo gunboats and five third-class cruisers, at the cost to the Australian colonies of £106,000 per year.

The logistical difficulties of British imperial defence continued to increase with the European fiscal crisis which accompanied the financial collapse of 1892–93. As Australia became a nation in 1901 colonial naval brigades also struggled to survive. However, Australian naval volunteers demonstrated their willingness to serve and their professional competence during the South African War (1899–1902) and the Boxer Rebellion (1900–01). Britain requested the release of three Australia Station ships to safeguard British interests and citizens in China. A force of 500 naval personnel joined the International China Field Force. Also included was Protector under the command of Captain William Creswell, who had been appointed Commandant of the Queensland naval forces on 1 May 1900. Protector arrived in Chinese waters during September 1900. Creswell firmly believed the ship ‘commissioned and manned in Australia was efficient for active service’.6 He was not surprised when a visiting RN officer ‘marvelled’ how hard the ship’s company worked. ‘I knew them, and their desire to make themselves and their ship as fit as possible for active service.’7 When the Admiral of the Imperial Fleet, Sir Edward Seymour, asked him what additional assistance the crew of Protector needed with coaling, Creswell replied that none was required. The Admiral retorted ‘Ho, going to teach us how to coal is he? Better send a committee of officers to see how he does it’. Protector’s men reacted favourably to Creswell’s faith in them and the following day completed the coaling in half the time allowed for the exercise by imperial authorities. Creswell wrote with obvious pride: ‘As we swung clear the flagship made the commendatory signal, “Very well done”’.8

Six Australians died on active service during the Boxer Rebellion, including Able Seamen J. Hamilton and Eli Rose from NSW and Boy Seaman A. A. Gibbs from Victoria.

During the 20th century the expanded strengths of international navies severely challenged the premise that Britain ruled the waves. Royal Navy Pacific squadrons were rapidly being overtaken by fleets of more modern and technologically advanced warships. The British Government believed it even more imperative that the dominions to the south should finance an imperial fleet. Operating simultaneously was the belief amongst British naval leaders in the Rear Admiral Alfred Mahan (US Navy) strategic philosophy of ‘one sea, one fleet’ and the ensuing belief that the key to efficiency was uniformity and interchangeability of ships and men. The Admiralty continued to emphasise the importance of naval defence officered and manned by members of the RN. Britain observed sea defence from a broad base of imperial global defence. Those in the Antipodes saw naval defence in the more simplistic terms of their own protection. Australians felt increasingly vulnerable due to the distance from Britain and the largely antiquated RN ships.

Under the Naval Agreement Acts 1902–03, Australia and New Zealand agreed to contribute to the maintenance of an RN presence for a further decade on the proviso that the Admiralty provided a strengthened fleet in the Western Pacific and maintained Australian territorial integrity. But the agreement and the annual cost of £200,000 were not popular within the Australian Parliament, particularly as the promised fleet failed to materialise.

In 1902 Creswell advocated an independent Australian navy:

Sea defence is of vital importance to island peoples, there can be no sea defence without seamen. If our shipping and sea trade is manned by foreigners who have no interest in defending us we shall have neither seamen nor sea defences.9

Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Fanshawe, RN, Commander-in-Chief Australian Squadron between 1902 and 1905, publicly disapproved of Creswell’s beliefs and criticised Australia for not supplying the British Admiralty with sufficient funds for the maintenance of his squadron. In communication with the Lords of the Admiralty, Fanshawe spoke of Creswell in cautionary tones as one ‘not in sympathy’ with the imperial navy cause. He also voiced concern that the careers of RN trained naval personnel could be affected ‘by the entry of colonial men’.10 The Admiralty wished to maintain strategic control but, on the eve of his return to England, Fanshawe apologised to his superiors that although he had strongly argued that ‘local defence was entirely opposed to British naval policy’ he had been unable to convince the Australian Government ‘to relinquish their local navy’.11 Creswell considered:

It was an opposition I have reason to know, such as only the Admiralty is capable of: an obstinate resistance of unhallowed tradition; and obduracy, inflexible and implacable, against which ordinary mortals beat their knuckles in vain.12

The British press was equally unsupportive. The Times believed that a Commonwealth of Australia navy would result in ‘a nondescript force of inadequately trained naval volunteers’ and ‘manned mainly by amateurs would be expensive to maintain in time of peace and absolutely ineffective in war’.13

Despite the reluctance of the British Government, the Admiralty and the British press to encourage local naval development, or perhaps because of this reluctance, the Australian Labor Government declined to renew the naval agreement in 1904 and chose instead to unify the colonial navies into the Commonwealth Naval Force (CNF). On 25 February 1904 Creswell was appointed Naval Officer Commanding the CNF. Protector, Cerberus, four Victorian torpedo boats, the Queensland flat-iron gunboats Paluma and Gayundah and two Queensland torpedo boats formed the fleet nucleus. CNF personnel numbered 239 officers and men with an additional 1,348 serving in the naval brigades.

Seamen like Ernest Fleming Blake and William Alfred Waddilove who would both even-tually join the crew of Australia’s first submarine, AE1, watched developments with great interest. Whilst men in important positions debated in cigar-smoke clouded offices they simply wanted to serve at sea.

img alt="i11" src="../Images/i11.jpg">

Stoker 1st Class Ernest Blake (7876) was born in the Brisbane, Queensland, suburb of Norman Park on 5 March 1892. He had no shortage of siblings. Mother Mary was the widow of Charles Stratford, by whom she had six children. She married Edward Blake and had seven more. Ernest enlisted in the CNF, not yet 18, looking to improve his life with full-time employment and a career which promised much. His red hair and ruddy complexion undoubtedly saw him nicknamed ‘Blue’. Having served with the Australian Squadron he was sent to England as part of the first contingent enlisted in the RAN for a period of five years. His previous CNF service was allowed to count towards his first Good Conduct Badge (GCB – also known as Chevron).14 His world had just got a lot larger and with character assessment of ‘Very Good’ (VG) and ‘Superior’ for ability, his future naval career looked very bright.

Born in West Melbourne, William Waddilove served on the elderly monitor Cerberus with the Victorian brigade and hoped that he might soon join better ships. His small

5 feet 4¼ inch (164cm) compact size may have enabled the dark haired Victorian to move around the ironclad without difficulty but living conditions were terrible.

When Sub Lieutenant Henry Feakes reported to assume duties as the First Lieutenant of Cerberus in 1907 he was met by an elderly rating15 who escorted him below with an oil lantern ‘through the dingy gloom’, just light enough to see fat, sleek rats scurry through the shadows. Feakes was clearly unimpressed:

Not since an armoured belt had been clamped around her ample waist upwards of 40 years before had God’s fresh air, or germ-destroying sunshine, penetrated into the vitals of the old ship. Forty years of potted air and bilge! The smelly oil lamp did the rest.16

His seaman guide had spent 36 years on the ironclad and had never left Port Phillip Bay.

William Waddilove hoped for brighter opportunities with the formation of the CNF and his experience allowed him to be accepted in this new navy as a Leading Stoker (7300). He spent time on HMS Psyche and then the opportunities exceeded his wildest dreams because shortly afterwards he too was in England for training. With ‘VG’ marked beneath ‘Character’ on his service report and the successful completion of his education certificate, he was promoted to Stoker Petty Officer. Another ‘VG’ and he was accepted for the mysterious and intriguing submarine duty. Perhaps being accustomed to the cramped, oppressive interior of Cerberus would be useful and Australia’s first submarine, AE1, would be almost roomy.

In 1905 Creswell had recommended that nearly £1.8 million be spent over the next five years on an Australian fleet of three 3,000 ton destroyers, sixteen 550 ton torpedo boat destroyers and 13 torpedo boats. The following year the Alfred Deakin Protectionist Party Government sent Creswell to England to familiarise himself with developments in naval shipbuilding. He found himself ‘a disaffected person’ at Whitehall.17 Admiralty officials were ‘frosty to extreme’ and he was treated like a foreign naval attaché at the dockyards he was permitted to visit.18 The British Government, committed to a reduction in its own defence spending, needed the dominions to continue their cash subscriptions to the British Exchequer. It came as little surprise in May 1906 that the report of the Whitehall-based Committee of Imperial Defence upheld the 1903 naval agreement and again suggested the programme of Australians manning RN ships. The committee believed Australian proposals were:

based upon an imperfect conception of the requirement of naval strategy at the present day, and of the proper application of naval forces.19

Unlike most of his RN counterparts, Creswell fully realised the geographic demands of safeguarding the interests of the world’s largest island – surrounded by testing oceans and tropical to frigid weather patterns – and consequently never advocated a small coastal force for Australia. But he met with such indifferent resistance and wrote that the ‘arrogance of the Admiralty was a major factor that almost insured that the Australian Navy was aborted before birth’.20

The tussle for control and development intensified with the election of the Andrew Fisher Labor Government in 1908 and the appointment of George Foster Pearce as Minister for Defence. Pearce was born on 14 January 1870 at Mount Barker, South Australia, of English parents. Like most of his generation and the next, he struggled to find the balance between loyalty to his British heritage and love for the very different country of his birth. Pearce was from a humble working class family, his father was a blacksmith and the family struggled to survive during the 1891 depression. Pearce was a union man and Labor through and through. He had little formal education but inspired confidence through his industrious and methodical work ethic; he was ‘attentive to detail, trustworthy, moderate and ready to pay more than lip service to principle’.21 In 1901 Pearce had been critical of British imperialism and warned that ‘Australia was in danger of being reduced to a mere component part of the British Empire’.22 The impact of Japan’s annihilation of the Russian fleet in the May 1905 Battle of Tsushima was pivotal to Pearce’s defence priorities. Pearce realised Australia needed to maintain strong defence relations with Britain but he also believed that the strategic emphasis needed to be more on the Pacific and Australia’s safety. This philosophy was not shared by the British Government. Not only had the British Government signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902 and renewed it in 1905, but the RN China Squadron’s five battleships were recalled to European waters. Australians felt abandoned.

In August 1908 over half a million Sydneysiders, nearly half the population of the city, turned out to watch the arrival of the United States (US) Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’. It was the largest crowd the nation had seen, far exceeding the number who celebrated the Commonwealth’s foundation. A very warm reception was accorded the crews of the 16 white-painted battleships during ‘Fleet Week’, in every port during the 14-month, 45,000 mile global circumnavigation.

The arrival of the massive naval force of the United States was less popular with Admiralty representatives in Australia than with the Australian people but it was the final impetus needed. Within the halls of the Australian Parliament the debate concerning the nation’s navy raged. On opposition benches there was support for the British request that Australia and New Zealand each finance a dreadnought cruiser for the RN for deployment in European waters. Three destroyers were ordered in February 1909 as Pearce agitated that for Australia those having ‘darker skins than Germans’ posed a greater threat. Whilst essentially referring to the Japanese, he also voiced the concern of his countrymen about ‘the “hordes of semi-barbarians” to the north’.23 Pearce and his Prime Minister ardently believed that to survive, Australia needed to rapidly develop an independent navy. But Australia and its navy would be destabilised by seven changes of government and 11 Ministers for Defence in the first dozen years of the Commonwealth.

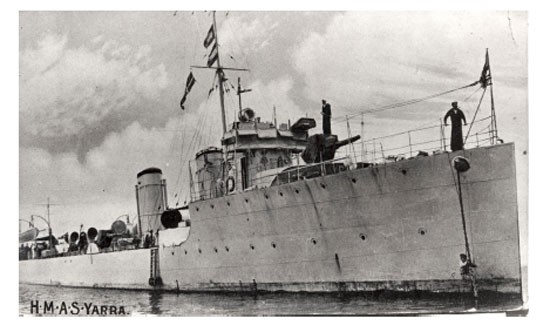

An order was placed with Britain’s Fairfield shipbuilding company for the construction of three 700 ton destroyers capable of 26 knots. They would be named Parramatta, Yarra and Warrego. These improved River Class destroyers were designed not under Admiralty authority but by Australian naval and technical officers advised by Glasgow University’s Professor Biles and were considered superior in speed and armament to any British warship in commission. Furthermore the Government proposed to build 16 River Class and four Ocean Class destroyers as a flotilla for coastal defences.

At the Imperial Conference in London in the summer of 1909 a plan for the establishment of an Australian fleet unit was finally implemented. Although it was becoming increasingly clear to many that the dream of imperial federation was fading fast, the Admiralty only grudgingly accepted the notion of a separate Australian navy. The German naval build-up and the resulting British media hysteria ensured that any Admiralty support diminished. Australia was represented at the conference by the leader of the new Protectionist Party Government, Alfred Deakin. It is written of Deakin that he was:

the embodiment of dual nationalism; pride in Australia went hand-in-hand with pride in the Empire … He had a mystical faith in the virtues of the British race and his vision was of great White Australia living at one with and within a greater white Empire.24

These joint loyalties meant that compromises were made and although the Australian Prime Minister continued his argument for an Australian fleet he agreed to an Australian unit which would consist of small coastal 360 ton destroyers and a small flotilla of submarines. Deakin also committed Australia to a shared financial plan with the Admiralty to construct a number of ships, the first being a battle cruiser of the Indefatigable Class, to be named Australia. In return the British Government promised it would establish two other fleet units. One unit would be placed on the China Station and the other based in the East Indies. Australia’s total contribution to this endeavour was to be £3,000,700, or £750,000 annually.

On his return to Australia Deakin was ridiculed for his acquiescence and his Australian fleet unit was nicknamed ‘The Tin Pot Navy’.25 The Australian unit was finally implemented and although it was to be manned by Australian officers and men, the policy governing Australian personnel would be the same as that governing those of the RN. The implementation of the personnel policy would be the responsibility of the RN until Australians were sufficiently trained and had accrued the required seniority to assume all positions. The understanding was that the RN would provide instructors. Creswell had concerns. He had recommended that a navigation school be established years previously and a training ship secured so that Australians could be prepared. Little had been done. The attainment of capital ships was proving easier than to implement a training regime for Australian volunteers.

Within the halls of the Australian Parliament the game of political musical chairs continued. Andrew Fisher became Prime Minister again in 1910 and his government was ‘imbued with a sense of Australianism’.26 Through the enthusiasm of the returned Minister for Defence, Senator George Foster Pearce, defence again took a position of priority. The British Government had reneged on promises made at the Imperial Conference in 1909 and much later it was admitted that ‘the subsidy was inadequate compensation for the misuse of the ships of the Australian Squadron’.27 The two British naval units promised had not been forthcoming. Warships left on the China Station were not the modern ones pledged. British Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, argued to retain warships financed by the colonies in British waters as a means of reducing British naval expenditure without reducing naval protection to the British Isles.28

In 1911 Churchill was given the portfolio First Lord of the Admiralty and within a year he directed that ‘every ship possible should be brought home from Australian waters’.29 Churchill argued that the two colonial dreadnoughts should not be sent to the Pacific. He believed older warships ‘could perfectly well discharge all the necessary naval duties’.30 The people of New Zealand, who had financed the Indefatigable Class New Zealand and who had been led to believe the ship would be stationed in their own waters, were now told the vessel would be kept ‘indefinitely at home’, in the Northern Hemisphere.31 While Churchill postulated about the imperial fleet and the safety of the dominions his concern lay firmly at home and even the Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, observed that Churchill failed to consider the concerns of the British dominions and that the Imperial Squadron was ‘a stillborn proposal’.32

The Australian Government had finally wearied of British procrastination and concluded that the country would need to be more responsible for its own navy. No member of the British Cabinet or Admiralty chose to attend the launching ceremonies of Australia’s first ships, Parramatta and Yarra.

The financial agreement with the British Government was cancelled and an order was placed for three 5,400 ton Town Class light cruisers, to be named Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson was invited to visit Australia to advise on the development of the Australian Navy. Australia’s first Naval Defence Act was passed, setting the legal status and administration of the naval forces of the Commonwealth and establishing the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board (ACNB). At the 1911 Imperial Conference in London Pearce finalised arrangements between the RN and the Australian Naval Force (ANF) and returned home convinced that war between Britain and Germany was inevitable. On 11 July 1911, King George V granted the Permanent CNF the title of Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and in October it was pronounced that Australian warships were to be prefixed HMAS – His Majesty’s Australian Ship.

For supporters of an independent Australian navy this was a triumph, but dissension and antipathy remained. Deakin had struggled with split loyalties; so too did others in Australia. To the majority of Australians Britain was ‘home’ and their affections were passed to their children. Loyalty to Britain and loyalty to the British Empire were inextricably tied. Some Australians considered a separate navy to be anti-British. The scope of the Henderson Plan and particularly the proposed cost increased the dissension, as did ‘a small but ardent minority opposed to the whole concept of naval defence’.33Admiral Sir Richard Poore, RN, Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Squadron was one of the more outspoken critics. Those on the front benches of the Australian Parliament vowed to confront this conservative movement which for years ‘had tried to do away with our Navy’.34

In a rare consensus the Australian print media applauded the Labor Government on the expenditure of public money for the procurement of Australian warships. The Argus took pains to remind the public of the need for a naval strength which would not only ‘deter the hostile from invading us, but should make friendly nations eager for an alliance with the empire of which we are part’.35 The Age believed such expenditure was timely and would forestall ‘a powerful conservative movement which had been inaugurated with the covert object of preventing the growth of colonial Navies’.36

The new Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Squadron, Admiral Sir George Fowler King-Hall, RN, was impressed with Andrew Fisher and Defence Minister Pearce and found himself supporting the idea of a separate and strong Commonwealth navy. During discussions they agreed that this would develop not only Australian nationality but also the authority of the Australian Government. The opinion being expressed by their representative in Australia did not please the Admiralty. King-Hall wrote in his diary on 26 February 1912 that he had received a long telegram from his superiors deploring the Commonwealth’s proposals. One telegram came from the Second Sea Lord, Vice Admiral Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg (soon to be Admiral Louis Alexander Mountbatten and First Sea Lord).

Heard from Battenberg last mail. He takes a limited view of the Navy policy initiated and being so successfully carried out by the Commonwealth. Wrote him a pretty strong letter in reply.37

King-Hall’s support of the Australian Navy ended on the issue of control. On this he agreed with his superiors, that authority over the RAN should rest with the British Admiralty and its flag representative. In 1913 in his briefing with the new Commonwealth Liberal Party Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, he reiterated that policy. When Cook expressed the opinion that Australia’s most senior naval member, Admiral Creswell, could take command, King-Hall hastened to ‘put him right on that score’.38 King-Hall reflected on a waning of enthusiasm on the part of the new government on naval policy, and was ‘not so favourably impressed’ with the new Minister for Defence, Senator Edward Millen. King-Hall implored Millen to keep politics out of naval matters and to continue to promote the Henderson Plan encouraged by the previous government. But the new government was preoccupied with politics and with denying the Labor Party credit for the establishment of the nation’s navy. Ex-Defence Minister Pearce countered: ‘If eloquent speeches could have built a navy, we should have had the biggest Navy in the world’.39

Whilst politicians debated about recognition, budgets and control, the naval careers of Australians hung in the balance. Although the Australian colonies had united under one flag in 1901, it was 1904 before the colonial naval forces came under Commonwealth regulations. The alliance was an uneasy one with accusations of favouritism. The creation of the CNF did not immediately extinguish colonial rivalries nor did it immediately extinguish rivalries between the different colonial naval militia. The transition caused problems for administrators – problems which would worsen as RN and ex-RN personnel were utilised to make up the personnel shortfall within the Australian fleet. Such division did little to encourage a cohesive service.

The lives of members of the RN lower deck (sailors) were harsh and there were deep divisions between them and their officers. It had been common for RN commissions to be conferred on individuals who were nominated by senior officers, and many officers had entered the RN through family connections. Between 1880 and 1898 only two members of the lower deck gained RN commissions; the service was ‘frozen into rigid classes and the gulf between Quarterdeck [officers] and Lower Deck [sailors] was wider than it had ever been’.40 RN officers who served in the Australian Squadron had long struggled with high desertion rates amongst RN seamen in Australian ports. The causes of desertions were complex but Australian society and ‘the great emotional attraction of a free and easy society for men accustomed to English conditions and naval discipline’ was largely held to blame.41

In 1907 the Admiralty had admitted it wished to discourage the recruitment of colonial seamen because, apart from their being ‘much more expensive’, they ‘can never be trained so efficiently as the men enlisted at home’.42 When the Admiralty agreed to the recruitment of ‘colonials’, it was intended only to encourage an ‘interest in the navy and to develop the maritime instinct of the Colonies’.43 RN officers had also long considered that the entry of Australian-born Stokers into Australian Squadron warships caused ‘considerable discontent’.44 Another problem arose because Australian Ordinary Seamen were better paid than British Petty Officers. The RN standard wage of £25 per annum had remained unchanged since 1853. RN trained officers had derived a poor impression of their colonial charges and this would linger. British administrators considered men nurtured in colonial societies made for unsuitable naval recruits. They believed Australians displayed ‘democratic instincts’, that there existed in Australian society a resistance to ‘the established order’. 45 The origin of this resistance was attributed to ‘the Irish element’. Australian ratings were seen as a bad influence on their RN counterparts.

John Joseph Moloney (7299) may well have been one of these, being a Stoker and of Irish descent. Born in the Brisbane suburb of Capalaba, on 25 January 1889, the son of Joseph and Alice Moloney, he tried to demonstrate his enthusiasm for his chosen career. Stokers were no longer merely strong, tough men who shovelled coal into insatiable furnaces. For a Stoker 2nd Class to advance to a Stoker 1st class required:

efficiency as a fireman when boiler is working at full power; ability to attend and lubricate a bearing; knowledge of the names and uses of the principal tools in ordinary use in the Engine-room Department; an intelligent use of the more simple ones, e.g., spanner, hammer and chisel, file, screw-driver; ability to plait gasket for packing; a fair knowledge of the ‘Stoker’s Manual’; in addition a fair knowledge of Rifle Exercise will be required.46

The ‘Stoker’s Manual’ included the chapters: Raising Steam, and Management Under Way; Pimping, Flooding and Drainage; Water-Tube Boilers and The Steam Engine. Promotion to Leading Stoker required three years as a Stoker 1st Class and a three-month mechanical course which included fitter and turner, boilermaker and coppersmith instruction.

John Moloney was promoted to Leading Stoker on 17 December 1912 and then after a ‘minimum period of service with good conduct, a certain standard in general educational subjects’ 47 he was promoted to Stoker Petty Officer on the first day of 1913, the month before he joined to train for service on Australia’s first submarine, AE1.

Within the first decade of the 20th century the total naval personnel in the Australian Squadron averaged 4,000. The Australian-born personnel component was restricted to below 20 per cent of this number. Australian ratings were seen as having a less respectful disposition than British ratings. This may have been an accurate assessment if the impression of colonial seaman Able Seaman Harold ‘Lofty’ Batt (7442) had of the Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Squadron in 1908, Admiral Sir Richard Poore, RN, was shared by his fellows:

Dickie Poore was bred in the old Navy tradition when men amounted to less than a coil of rope … To him, Colonial Matelots did not amount to much, they didn’t give a damn about standing smartly to attention and saluting every brass button that came along, and he didn’t like that.48

In his final days of command, Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Squadron, Admiral King-Hall, had struggled with problems on board HMS Torch as the vessel lay off Noumea. Australian ratings served in the ship’s company. Both the ship boilers were out of action and it was estimated that repairs would take five weeks. It was not conclusive as to whether the damage had been due to carelessness or had been deliberately caused. Admiral King-Hall had decided not to make the situation public in an effort to avoid scandal and because he feared the Admiralty would be furious. Naval administrators had developed a pattern of response to unrest within the lower deck. They had chosen to treat the consequence rather than the cause, to attempt to resolve unrest with increased disciplinary measures; this only ensured continued unrest.

The 1909 naval agreement had specified that Australian naval training and discipline should be uniform with that of the RN to enable the interchangeability of officers and men but ‘the British Admiralty consistently refused to help the Dominions “play the game” by any rules except their own’.49 No deviation from this agreement was deemed acceptable and the Admiralty informed Australian authorities that it would supply suitable men to act as instructors. RN officers would be loaned to administer the service. Australia agreed to pay approximately £750,000 to Britain for maintenance, pay and allowances for loaned personnel, training and other associated costs.50 The history of the RN was long and specific traditions in the treatment of men of the lower deck were well-established. The RN of the period has been described as one suffering from ‘general stagnation’ of a service ‘hidebound by tradition and it was often the less glorious side of the tradition that most affected the lower deck’.51 This tradition was now to be imposed on Australians.

For the new Australian Commonwealth Naval Board (ACNB) the prospect of raising the required Australian Naval Force (ANF) was daunting. The Henderson Plan forecast that Australia would need to recruit 13,832 officers and men. It was also anticipated that at any time an additional 1,012 would be under training. The Argus newspaper believed there would be limited success because Australians were not seafarers and the interests of the young men of the country ran to the ‘delights’ of the cities and the towns.52 Defence Minister Pearce admitted ‘we have a pretty big task’ but believed that as it became known that the Australian Government was now in charge of the navy Australian men would be attracted to the service.53

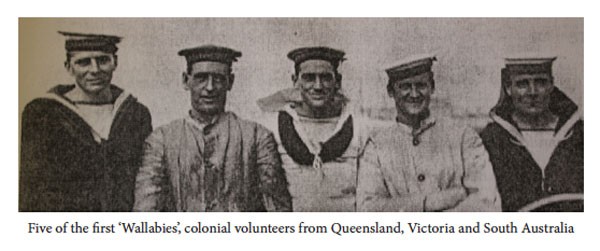

In 1910 naval personnel numbered a mere 1,240. By 1911 400 Australians were being trained within the Australian Squadron and between 200 and 300 were enrolled in the reserve. The RN made available some places within their specialist schools and in 1910 a contingent of naval personnel travelled to Britain to be trained in gunnery, signals, torpedo and engine room responsibilities before joining the destroyers and bringing home the first warships built for the Australian Navy. HMAS Parramatta and HMAS Yarra were commissioned on 10 September 1910. Members of the first ships’ companies (non-commissioned officers – sailors) had completed their courses at Portsmouth Royal Naval Barracks with impressive grades. The colonial seamen, 13 from Victoria and eight each from Queensland and South Australia, known as the ‘Wallabies’, were inspected by the Second Sea Lord, Vice Admiral Sir Francis Bridgman.

He was particularly impressed by the ‘fine, robust’ nature of the Australian sailors and noted with surprise that a large number of the men were decorated with both South African and China war medals, as well as long service and good conduct medals.54 He assumed the men had accumulated such awards as imperial naval ratings but the men quickly advised him they were all Australians who had served in the campaigns as members of the colonial navies.

The genesis of the new navy remained confused and confusing. Volunteers did not know who was in charge or how they would be treated and their futures were thus very unclear. Fifteen ratings left without completing their full terms of engagement, one was invalided, one was discharged in England, three were dismissed and 10 were permitted to leave due to their dissatisfaction with prospects. It was not an auspicious start.

One of those who chose to remain was Robert Smail (1068). By what would prove an interesting coincidence Robert was born on Australia Day (26 January) 1888 in Galashiels, Selkirkshire, Scotland, the son of Robert and Elizabeth Sherriff Smail. At 16 he entered the Merchant Service and sailed the Baltic for two years. He then joined the crew of the four-mast sailing ship, Loch Tay. The ship was becalmed for nearly a month en route to Australia with a cargo destined for Port Melbourne. Because they had arrived late their ‘back loading’ cargo had been loaded onto another ship, and as a consequence the Loch Tay crew were discharged. Robert was stranded but joined the coastal steamer Koomah and the more he saw of this new country the more he fell in love with it. The new navy was going through a transitional stage but regardless of what it wished to call itself Robert Smail applied to enlist for five years on 3 August 1908.

Robert quickly made a very favourable impression and with continuous assessments of ‘Very Good Character’ and ‘Superior Ability’ he was rapidly promoted to Petty Officer by 17 June 1911. The fair-haired, blue-eyed, handsome, 5 feet 7¼ inch (173cm), 23-year-old found himself returning to the nation of his birth as a member of the commissioning crew of torpedo destroyer HMAS Yarra. He returned home to Galashiels, Scotland, on leave and effused about the splendour of his adopted country to the point of persuading his parents to emigrate to Australia in 1911. On his eventual return to Australia Robert paid a substantial part of his savings on a deposit on a cottage at 14 Danks Steet, Albert Park, Melbourne, Victoria. In addition he forwarded the passage money to his family and committed himself to supporting his parents and four younger siblings.

Petty Officer Smail was a pivotal member of Yarra’s crew which farewelled Britain from Portsmouth Naval Base on 19 September 1910, accompanied by sister ship Parramatta and HMS Gibraltar. Curiously these two 700 ton destroyers, which had been spurned by the Admiralty, remained under Admiralty control until they sailed into the port of Broome, Western Australia, on 15 November 1910, when they were formally passed to the control of the Australian Government.

The evolution of the Australian Navy had not been easy. It was derived from a climate of colonial rivalries, government instability and a population divided over the sentiments of nationalism and imperialism. Confused government naval policy in the first years following federation was exacerbated by the unwillingness of the British Admiralty to relinquish control. The future would test the relevance and suitability of RN standards, relationships and traditions on Australians and would have a direct bearing on their very safety.

FOOTNOTES

1 Bach, J. The Australian Station Station: a history of the Royal Navy in the south west Pacific, NSW University Press, 1986, p. 188.

2 The class of ship referred to as ‘monitor’ was directly derived from the American ship of that name, the USS Monitor designed by John Ericsson which served in the American Civil War.

3 Stevens, D. ‘1901–1913 the Genesis of the Australian Navy’ in Stevens, D. (ed.) The Royal Australian Navy, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Volume III, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 8.

4 Nicholla, B. ‘William Rooke Creswell and an Australian Navy’, in Frame, T.R., Goldrick, J.V.P. and Jones, P.D. Reflections on the Royal Australian Navy, Kangaroo, NSW, 1991,

pp. 42–51.

5 MacAndie, G.L. The Genesis of the Royal Australian Navy, Government Printer, Sydney, 1949, p. 31.

6 Parsons, R. Navy in South Australia, self-published, South Australia, 1974, p. 8.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 A5954/1, 1924/8, National Archives, Canberra,

10 Admiralty Minutes, PRO.6916, Adm. 1/7730, Report to the Admiralty, 6 April 1904, AJCP.

11 Ibid., No.83/1824, 20 February 1904.

12 Thompson, P. (ed.) Close to the Wind, Heinemann, London, 1965, p. 199.

13 MacAndie, p. 74.

14 Good Conduct Badges were issued after three years, eight years, and 12 years. If three Good Conduct Badges were earned a man qualified for a Good Conduct Medal and this came with a monetary bonus. Any loss of good conduct and subsequent badges meant quite significant loss.

15 ‘Rating’ was the official term for a member of the lower deck – a ‘rate’ meant the occupation or category to which a sailor belonged, e.g. Stoker. It was also the name given to the badge depicting a naval occupation which a member of the lower deck of the RAN wore on his right sleeve.

16 Feakes, H.J. White Ensign Southern Cross, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1951, p. 120.

17 Ibid., p. 117.

18 Jones, C. Australian Colonial Navies, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1986, p.140.

19 MacAndie, p. 163.

20 Jones, p. 117.

21 Beddie, B. ‘Pearce, Sir George Foster (1870–1952)’, in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 11, Melbourne University Press, 1988.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Pike, D., Nairn, B., Serle, G. and Ritchie, J. (eds) Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 8, p. 256.

25 Ferraby, H.C. The Imperial British Navy, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1918, p. 48.

26 Greenwood, G. (ed.) Australia: a Social and Political History, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1977, p. 227.

27 Tracy, N. (ed.) The Collective Naval Defence of the Empire, University Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. xiv.

28 Lambert, N. ‘Economy or Empire?’ in Kennedy, G. and Neilson, K. (eds) Far Flung Lines, Frank Cass, London, 1996, p. 68.

29 Ibid., p. 71.

30 Ibid., p. 68.

31 The Daily Mail, 30 June 1913. ‘HMAS Australia Press Cuttings’, HMAS Cerberus Museum, Victoria.

32 Overlack, P. ‘Australasia and Germany: Challenge and Response Before 1914’ in Stevens, D.M. (ed.) Maritime Power in the 20th Century, Allen & Unwin, 1998, pp. 33–35.

33 Henderson, Admiral Sir R. The Naval Forces of the Commonwealth: Recommendations, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1911. Le Tet, S. ‘Australian Attitudes towards Naval Defence 1901–1903’, ARTS IV Thesis, University of New England, 1983, p. 49.

34 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXX, 3 September 1913, p. 807.

35 The Argus, 14 March 1911.

36 The Age, 27 August 1913.

37 King-Hall, G. ‘Diaries of Admiral Sir George King-Hall, 1911, 1912, 1913’, unpublished, Sea Power Centre, Canberra, entry 9 January 1912.

38 King-Hall, entry 18 July 1913.

39 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXI, 13 September 1911, p. 350.

40 Carew, A. The Lower Deck of the Royal Navy 1900–1939, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1981, p. xiv. Traditionally in the RN the collective name for ratings was the ‘Lower Deck’, the collective name for officers was ‘Quarter Deck’ and later ‘Wardroom’. These names were derived from the part of the naval ships where the separate groups were accommodated. ‘Lower Deck’ dated from the days of wooden ships when sailors quarters or ‘messdecks’ were situated on the lower gun deck.

41 Bach, p. 237.

42 Memo by Langdale Ottley ‘Admiralty Views on the Working of the Australian Naval Agreement’, 27 February 1907, in Tracy, p. 69.

43 Bach, p. 237.

44 Feakes, p. 111.

45 Bach, p. 238.

46 HMAS Cerberus Museum, ‘Stoker’s Manual’, Office of Admiralty, London, 1912, p. 121.

47 Ibid., p. 123.

48 Batt, L. Pioneers of the Royal Australian Navy, self-published, NSW, 1967, p. 40.

49 Lambert, N. ‘Economy or Empire’, in Kennedy and Neilson. (eds) Far Flung Lines, p. 58.

50 MacAndie, p. 242.

51 Carew, p. xiv.

52 The Argus, 25 February 1911.

53 The Argus, 17 March 1911.

54 Feakes, p.141. A Good Conduct Medal was awarded after years if rating had not less than good conduct.