CHAPTER TWO

‘Your true-born sailor loves the sea for itself. He may grumble at its hardships and disabilities … but is still irresistibly drawn to it.’

The Argus 25 February 1911

At the commencement of the first RAN recruiting campaign 10,000 copies of the booklet How to Join the Royal Australian Navy, were distributed.1

The Naval Depot at Williamstown, Victoria, which acted as the interim training depot for general entry recruits, had very limited accommodation so recruiting could not begin until the middle of 1912. Those who wished to join as normal entry had to be ‘smart active youths and young men between the ages of 17 and 25 years, of very good character’. If they were aged 17 to 19 the physical minimum requirements were a height of 5 feet 2 inches (157cm) and a chest measurement of 33 inches (84cm). Candidates were required to pass a medical test and an education test. To pass the standard entry education test aspiring naval ratings needed to read a passage from ‘a Standard IV reading book’, write dictated passage of approximately six lines, and prove a ‘fair knowledge of the first four rules of arithmetic’.2 The warships being built for the RAN incorporated the newest technology and sailors needed to be a new breed of rating – being merely strong and able-bodied no longer sufficed. Ratings needed to be literate and capable of undertaking technical training.

Gordon Clarence Corbould exemplified this. Born on 10 April 1887 to Ernest and Alice Corbould, Gordon grew up in the family home of ‘Ashledoin’, Essex Road, Epping, New South Wales, and he epitomised the bronzed Aussie. Gordon loved everything about the sea and became a member of the Tamarama Surf Life Saving Club. As soon as he could he enlisted in the ANF and in April 1911 he was an Able Seaman at Portsmouth, England, receiving additional training. He had little difficulty passing his examinations for Leading Seaman in November 1912 and was pleased to enlist for seven years in the Royal Australian Navy on 17 December 1912 and destined to be drafted to Australia or Sydney which would depart from England the following year.

Initial enlistment was for five or seven years. A syllabus for the basic training of volunteers was released in July 1911. It consisted of physical drill including swimming and lifesaving; rifle and field exercises to company drill; boat work (rowing and sailing); seamanship (rope knotting and splicing); Morse, semaphore and flag signalling; field and quick firing gun drill; target practice and musketry and, of course, marching – lots of marching.3 On selection each recruit received a ‘kit’4 a generous issue of uniform and undergarments. Even if invariably the items of clothing were too big, too small, too long, too short and rarely fitted perfectly, the ‘kit’ consisted of more clothing than most recruits had ever had. Basic training wasn’t easy but for many it was the first time in their lives they could depend on three meals a day and access to free medical and dental treatment; this was beyond the average citizen.5

Such was the case of Able Seaman Jack Jarman, RAN (1138), who enlisted for five years in the month the basic training syllabus was enacted. Jack was born in Dookie, Victoria, on 11 June 1893, to William and Elizabeth Lucy Jarman (nee Bennett) and his sister Catherine Lucy followed the next year. With the death of William life was a struggle for Elizabeth, Jack and Catherine until Elizabeth married Pat McGrath in 1909 and the family moved to Melbourne. Cast into the role of the man of the family at a very young age, Jack struggled with a strong sense of responsibility for the welfare of his mother and sister, and this and a draft to HMAS Parramatta caused problems in his navy career. But in the earliest stage his enthusiasm was high and he moved from the rating of Officer Steward to Able Seaman. When Elizabeth saw her only son next she was proud of his uniform and maturity, even if she just had a few reservations about the tattoos. Perhaps it was best not to ask who ‘Nellie’ was over ‘clasped hands’ on his right arm. Elizabeth wasn’t entirely sure she was comfortable with the ship in a wreath – it seemed a shade ominous. The full rigged ship, shield and heart, floral design on his left arm and hand seemed a tad excessive as did the combination of three horseshoes, heart and cross on the right arm. Jack never seemed to do things by halves.

For Australia’s navy particular attention was paid to the recruitment of volunteers with trades. It was proposed that at least 20 per cent of the personnel would have technical skills and specific numbers of electricians, blacksmiths, carpenters, plumbers, ‘mechanicians’ and men with other trades were sought.

John James Bray was born on 5 May 1891 in Eaglehawk, Victoria. He was the eldest of five children to John Blue Bray and wife Alice (nee Harvey). John was named after his father and paternal grandfather but was called ‘Johnny’. He grew up in a stone cottage built by his Cornish stonemason maternal grandfather in Eaglehawk, Bendigo. Generations of Bray men were miners and too many died in mining disasters or with health problems derived from life working underground. Johnny’s father died prematurely in 1913. Perhaps the dangers of being a miner dissuaded Johnny from following the family tradition or perhaps it was due to his slight physical frame but the young Victorian apprenticed initially as a blacksmith. As strange as it seemed to this mining community Johnny had an ‘earnest desire to join the navy … when 16’.6 Johnny Bray became Navy No. 1604 and proudly had himself photographed in his navy blues. He looked to exciting adventures and exotic ports and hoped that his family would be as proud of his new career as he was. Sent to England as part of the commissioning crew of HMAS Australia he volunteered to train for submarines.

Navies had progressed considerably since press-ganged seamen crewed sailing ships and this was reflected in the need for experienced and well-trained recruits. A candidate for the category of Armourer had to have previous experience as a ‘Whitesmith, Blacksmith, Enginesmith, Shipsmith, General Smith, Gunship, Fitter, Turner (Metal) or Cycle Machinist’.7 Candidates for the category of electrician were expected to be ‘thoroughly efficient Fitters and Turners’. Entrance examinations applied for most categories. Recruit painters were required to be:

competent to undertake plain painting work, mixing colours, writing and printing with brush and paint, oak and marble graining, gilding and repairing work, cutting plate and sheet glass with a diamond. To possess a knowledge of the preparation of the surfaces of wood and steel to receive paints and enamels.8

Sick Berth ratings were admitted only when they had a proven ability in ‘reading, writing and arithmetic’ additional to that required for general entry, while Cook candidates who had a proven aptitude for baking and cooking had also to prove themselves ‘educationally fit’ before they were entered on probation.9

As an added enticement came accelerated rank. Two highly thought-of technical sailors, who by coincidence had consecutive numbers, were ERA 3rd Class James Alexander Fettes (7290) and ERA 4th Class John Messenger (7291). They would become RAN recruiting poster sailors but John’s journey into Australian naval uniform had come with an interesting twist.

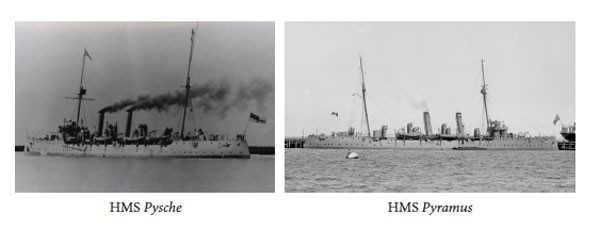

John ‘Jack’ Camerton Messenger was the eldest of the eight children of John Camerton Messenger and Isabella Elizabeth Messenger. For the previous three generations the eldest son was named John Camerton though it is unclear from where the name originated. Jack was a native of Ballarat East, Victoria, and was educated at the Golden Point State School, and at the Technical School to qualify as a draughtsman. His swift career change was not exactly foreseen or intentional. Jack got into a fight in a Melbourne pub and beat up his opponent so badly it was thought the man might die. Jack’s uncle hurriedly signed his nephew on as a seaman on a merchant ship bound for England. The other party in the argument survived and Jack decided to join the Royal Navy in 1908, doubtless in an effort to return home. Customarily for Australians within the Australian Squadron he served in Australian waters on HMS Pyramus and in 1911 finally managed leave to visit his relieved family in Ballarat.

James Fettes served with the ANF and was awarded his Good Conduct Badge in September 1913, having signed on to the RAN for five years in December the previous year. He was tall, 5 feet 8½ inches, dark and handsome and it is unclear who was represented in the heart tattooed on his left arm. By December 1912 he was in England undergoing further training and by February this training extended to submarines with his compatriot ERA John Messenger.

The Argus had advised its readers that navy recruiters would have limited success, because Australians were not ‘seafarers’,10 an interesting conclusion considering that regardless of the bush myth, Australians tenaciously clung to the shoreline of a land surrounded by ocean. By March 1911 Pearce announced that recruits were coming in so fast the navy could not cope and Williamstown was overcrowded.

To cover immediate personnel requirements Admiral Henderson had recommended the loan from the Royal Navy of 1,623 officers and men whilst recruiting 800 Australians. RN personnel wishing to transfer applied to the Admiralty through their commanding officers. Australian authorities had a preference for experienced, well-qualified ratings but could play no direct part in the selection process. The Admiralty governed who would come to the RAN and which officers and senior ratings would be in authority, placing the nascent Australian force at an obvious disadvantage with regards to quality, loyalty and numbers. The immediate effect would be to determine how many Australians could and would be trained.

It quickly became apparent that there was a breakdown in the training schedule of new recruits. Pearce laid the blame with the Admiralty which was not releasing sufficient instructors.11 He hoped RN co-operation would improve but by July 1911 Pearce’s office conceded this was not happening and the Admiralty, citing King George V Coronation ceremonies and reviews, admitted it was unable to accede to the request for instructors.12 The Admiralty now ‘regretted the agreement with Australia and in 1912 proposed to lend only Royal Naval reserve and merchant officers to the RAN’.13

The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board (ACNB) was also guilty of mismanagement or at least underestimation. Traditional thinking listed naval issues in the order of importance as strategy, materiel and personnel. Ships had been ordered quickly, yet there were no ship companies to crew them. ACNB was finding the implementation of personnel policy a more complicated procedure than the traditional order of priority would suggest – recruiting men in the Southern Hemisphere was rather different, opportunities were greater, more thought, more concern, more incentives needed to be offered. The Australian volunteer force had been depleted with the departure for England of the 70 officers and men in 1910 to bring out the newly constructed destroyers Parramatta and Yarra yet:

no steps had yet been taken to enter or train the personnel requisite for the manning of the cruiser building in Great Britain.14

In 1911 a 3,600 acre site on the shores of Westernport Bay, Victoria, was acquired for the main naval training base which would include a gunnery and torpedo school – a recommendation Creswell had made as early as 1904. Progress was slow. Until the Australian destroyers arrived fleet instruction would continue to take place on board Australian Squadron ships HMS Psyche and HMS Pyramus. Although both were relatively modern they were overcrowded, small and narrow-gutted; the current joke was that a man standing by the port (left side) railings could easily be seasick over the starboard (right side) railing.15 Victorian Stoker William Waddilove considered his move from the ancient monitor Cerberus to Psyche as an improvement – slightly.

Admission to the majority of seamen categories was open only to those recruited under the Boy Seaman entry scheme. At the cost of £15,000 the Commonwealth purchased the 317 foot sailing ship Sobran, to be converted into a training ship. Between 1891 and 1911 the New South Wales Government had used the vessel, known then as Vernon, as a nautical school ship for delinquent boys. Alterations were made to provide classrooms and improve accommodation, the vessel was commissioned in April 1912 as Tingira, and it was ready for the first intake of Australian Boy Seamen. Naval recruiters warned: ‘Only boys of a very good character and physique’ need apply.16 Boys had to be aged between 14 and 16 years of age and ‘boys who had spent time in reformatories or prison were not to be considered’.17

By October 1913, 300 boys had joined Tingira and naval authorities believed the steady stream of applicants would continue. The Sydney Morning Herald agreed there would be little trouble reaching the quota of boy recruits because parents with the best interest of their sons in mind knew that a career in the Australian Navy was ‘full of promise’.18 For so many this was not only a wonderful opportunity to feed, clothe and educate a son, when apprenticeships were scarce, but his salary would often mean a great deal to his commonly large family.

It was a lifestyle Cyril Lefroy Baker (1268) entered. Cyril’s middle name was in honour of the place of his birth, Lefroy, Tasmania, which in turn was named after Tasmanian Acting Governor Sir Henry Lefroy. When Cyril was born on 29 November 1892 the township was prosperous and basking in the glint of gold. His father was a miner and it was a profession Cyril, known to his family as ‘Buds’, may have expected would be his destiny also. Lefroy, north of Launceston and east of Devonport, was the fourth largest town in Tasmania. The population of 5,000 could frequent six hotels, three churches, private and state schools, a masonic lodge and a mechanics institute. It is likely the young Cyril spent time in the vicinity of the cordial factory, looking for some free samples to wash his way. He would have meandered through Chinatown on Powell Street, intrigued by the Chinese – their mysterious ways, strange clothes and long black pigtails – who sifted the tailings from crushing batteries when others couldn’t be bothered. They commonly survived by providing miners and their families with fresh vegetables. Their Joss House was built as a heavenly portal for spirits to descend from, its roof tilted up at the edges to deflect evil spirits as did the gargoyles.

By the time Cyril entered his teenage years the vein of gold in Lefroy had all but disappeared and the last large mine closed in 1908. The region was in decline and employment opportunities eroded in the dust. The navy was a reasonably unusual choice for a boy born into a mining community, but Cyril signed on as a Boy Seaman for five years on 19 October 1911. This Tasmanian teenager was about to undertake an amazing naval career, to visit places and see things his Lefroy mates could never envisage. But Cyril Baker never returned to grow old in Tasmania.

Once on Tingira boys were issued with a casual suit and a ‘kit’ consisting of three serge suits, four duck suits (light canvas suits), two collars, one uniform silk (type of scarf worn for ceremonial purposes, under collar), two towels, two flannels, one jersey, underpants, handkerchiefs, socks, two pair boats (shoes), brushes, lanyard (white rope worn around neck beneath collar), white, cap ribbon, belt, toothbrush, toothpaste, brush, soap and hammock. Civilian clothes were posted back to their next of kin. One boy wrote enthusiastically, ‘I never had so many clothes in my life’.19 Boys were paid 8/6d a week, 7/- automatically banked on their behalf. Shore leave was only granted when a boy had passed his swim test – that is, to be able to swim 100 yards clothed in naval uniform – and it was an offence to smoke until he reached the age of 16.

The Australian Boy Seaman training was based on that of the RN boy training ships which had started with HMS Illustrious in 1854 – the training curriculum had altered little since then. The RN treated its young recruits ‘with extraordinary conservatism’.20 And although by 1905 the Royal Navy had decided Boy Seamen would no longer be trained onboard sailing hulks, as Australia prepared to take receipt of technologically advanced warships in 1911, the decision was made to train its youngest recruits on a sailing hulk. The RAN also adopted a model which placed more value on tradition than on embracing the future. Between 1912 and 1927, 3,158 boys received their first naval training on Tingira moored permanently at Rose Bay in Sydney Harbour and life invariably was harsh.

At 5.30am reveille was sounded and boys turned out of their hammocks on the sleeping deck. Petty Officer Instructors were present to tip out boys who did not react quickly and to castigate anyone who did not lash his hammock with seven turns. Two divisions bathed and two divisions washed, alternating on a daily basis. A half-hour was given for a cup of cocoa, known as ‘Ki’ and a hard sea biscuit. All hands were then ordered to cleaning stations. The largest chore involved ‘holystoning’. This duty required boys to kneel on the deck and move a large flat piece of sandstone over the teak decks. Generations of naval ratings regarded this as their hardest duty and there was many a silent cheer when wooden decked vessels were replaced by steel.

At 7.30am hands were piped to breakfast. Boys then changed into the ‘rig’ (uniform) of the day and started their classes at 8.30am. Classes involved seamanship, physical training and some normal school subjects. Between noon and 1pm it was ‘hands to lunch’ with more classes in the afternoon. ‘Secure’ was piped at 3.45pm and following afternoon tea boys would be taken ashore to play football at Lyne Park or to the public baths; on Friday the boys were encouraged to participate in boxing matches. The highly organised days came to a close at 10pm when lights were extinguished. On Mondays and Thursdays all hands were mustered to scrub and wash clothes. On Wednesday morning boys:

were at the whim of the old man, (Commanding Officer) sometimes it was away all boats, pull around Rose Bay, another time it would be a morning’s sailing, in cutters and whalers. Other times it was a route march, with field guns, to the sand dunes of North Bondi …We were able to come to terms with these outings, because we knew we had the afternoon off.21

Saturdays were devoted to more cleaning in preparation for the weekly Captain’s rounds and some leave was permitted in the afternoon. Sydney natives were allowed occasional overnight leave. Being from Tasmania, Cyril ‘Buds’ Baker probably envied the opportunity of family comfort. Even when boys were entitled to three weeks midwinter leave and three weeks leave at Christmas, the vast distance between Sydney and Lefroy meant few home visits – a difficult adjustment for a youth.

Seamanship instruction was replaced by gunnery training. The weapons used were often obsolete but complete familiarity was demanded. Field gun teams practised until highly efficient. Considerable prestige was gained by the ship or depot which won the regular field gun competitions. For many the highlight of the week was the silent movie shown in Tingira’s canteen. The only distraction to the evening’s entertainment was the noise from the piano played by the Canteen Manager. He could only play one song and through westerns, dramas or comedies, the strains of ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’ continued with monotony. After 12 months on Tingira, Boy Seamen were drafted into the fleet.

Within a year Cyril Baker had signed on again, this time for seven years (man time) and he was now an RAN Ordinary Seaman on Protector. He celebrated by showing the world he was truly a ‘matelot’ or ‘bluejacket’ (popular names for sailors) by subjecting himself to the painful process of tattooing both arms. On the left it was a kangaroo and flag and on the right a heart and spear. Cyril was proving a smart lad and was selected to enter the exciting new world of telegraphy. In January 1913 he was back to Flinders Naval Depot, Westernport, designated Ordinary Telegraphist and commenced his six months technical training. On 25 July 1913 he was rated Telegraphist. From August 1913 he was part of the 29 officer and 269 sailor crew of the second class protected cruiser Encounter which had recently been transferred from the RN. He continued to learn his profession in preparation for a transfer to one of Australia’s first submarines which were soon to leave Britain.

360 experienced Australian ratings transferred to the RAN at its inception, but the lack of foresight on personnel policy and the ensuing delays meant the immediate manpower shortfall was significant. Australians joined Australia’s first new ship Parramatta in June with RN specialist ratings for the journey to Australia. HMAS Parramatta was commissioned at Greenock on 10 September 1910, and placed under the command of Lieutenant (later Rear-Admiral) H.J. Feakes, CNF. Feakes had come a long way from ‘the dingy gloom’ of Cerberus. Lieutenant (later Commander) T.W. Biddlecombe, CNF, commanded Yarra and both were under the command of Captain (later Rear-Admiral) F.W. Tickell, CNF, when the warships departed Portsmouth on 19 September 1910 for the voyage to Australia. When Parramatta arrived at Columbo an additional crew member was taken on board – a monkey, the ship’s first mascot. The monkey was very popular, except with Captain Tickell, who was not pleased with the creature’s habit of fouling the ship’s bridge. During the Indian Ocean crossing the monkey fell overboard and was drawn into the ship’s propellers. Parramatta’s sailors regarded this as a bad omen and considered their superstitions proven when the vessel sustained damage in the Straits of Sumatra. The first Australian landfall for Parramatta and Yarra occurred at Broome on 15 November. Eight days later they arrived in Fremantle to a frenzied programme of entertainment.

The destroyers’ crews were astounded by what was to follow and the depth of public interest. At Fremantle the local population had been swollen with the arrival of Commonwealth politicians and dignitaries for the State banquet which the West Australian declared:

A glittering occasion … to mark the first arrival in Western Australia of the two vessels forming the nucleus of the Australian Navy. 22

Celebrations in Melbourne, the then Australian seat of government, were clouded when on entering Port Phillip Bay, Yarra’s Engineering Officer, Lieutenant Commander Robertson, fell overboard and drowned. The ships remained in Melbourne to allow their crews long Christmas leave and it may have been at this time that Petty Officer Robert Smail visited his newly arrived family in the house he had purchased for them. In March they sailed to Sydney. At the official welcome conducted in the cricket ground 15,000 citizens waved and cheered as the Royal Australian Navy personnel marched. A large fireworks display filled the sky as the patriotic official speeches were concluded. Yet barely had the bunting and the banners been removed when rumours circulated suggesting that all was not contentment in the new force.

Recruiters had announced there would be little difficulty in raising the manpower required. Pay rates were good particularly when a rating was ‘doctored, clothed, lodged, fed, at no cost to oneself’ and the ‘permanent’ nature of naval employment was considered. The ‘fortunate few’ who were accepted would not only receive excellent training and the chance to travel extensively but the excellent opportunity ‘of climbing the ladder of promotion’.23 But these promises would in the immediate future fail the test of time.

HMS Challenger transported Australian sailors to Britain to commission HMA ships Australia, Melbourne and Sydney. Their optimism was high but short lived. One ex-ANF sailor wrote:

All the Colonial crew members, numbering six hundred, were transferred to the Challenger, to eventually become the officers of the new Navy, like hell they were.24

RN personnel held the majority of positions of authority. Whilst this could to a point be understood because of seniority and experience issues, RN officers had a history of preferring RN personnel over colonial seamen and were clearly unconcerned by the ratio of loaned RN personnel in the commissioning crews. Of HMAS Australia’s complement of 790, Australian ratings made up 372; Melbourne’s crew of 400 included only 190. Of HMAS Sydney’s crew of 400, 146 were Australian. The question: ‘Could fewer RN personnel have been accepted?’ is difficult to answer but it was vital to the cohesiveness and morale of the RAN and by 1913 there was no shortage of Australian-born volunteers.

The Argus newspaper’s doubt on the willingness of Australian youth to take up the challenge of maritime career was proven incorrect. Authorities estimated that 863 men were needed to commission the Australian fleet but by March 1913 a force of 1004 men had filled the training establishments to capacity. To restrict further applications the age of entry was raised. Concern for the ratings of the Australian Navy crossed political boundaries. The ‘politically conservative’ Queensland free-trade Senator Thomas Drinkwater Chataway announced in the Australian Parliament that there was ‘virtual mutiny’ on the warships, suggesting ‘something rotten’ was happening in the fleet.25 Concern had been rising since Sydney-born 21-year-old Ordinary Seaman Stanley Morris had committed suicide onboard HMS Pyramus.26 Too many former CNF personnel had applied for discharge.

Some politicians voiced concern over the adoption by the RAN of the discipline code of the RN. New South Wales Labor Senator, Alan McDougall, declared:

It is hard to bring Australians down to what men have to stand in the Navy of the Old Land and other navies. It is hard to break the spirit of the Australians. But let him know that he is in exactly the same position as the best on the vessel though holding a humbler position in life, let him know that one man is as good as another, and you will find that the Australian will be ready to take his place in the front fighting line, not only on the land, but at sea.27

McDougall’s words were prophetic. He had touched on the essence of the Australian naval rating. Nonetheless he still did not fully appreciate the strength of the naval culture imposed upon Australians. Labor Senator Arthur Rae, too, argued that British regulations would make it difficult to continue to recruit men for the RAN. Rae was a nationalist who believed there would be no acceptance among the men of the RAN of a discipline code derived from a class system. There were cries of support from the gathered politicians when he declared that such a discipline code would lead to unnecessary tyranny and unfairness on the part of superior officers in the management of men and concluded: ‘I trust we shall never allow anything of the kind to grow up in our Navy’.28

In February 1911, The Argus editorial had noted:

Your true-born sailor loves the sea for itself. He may grumble at its hardships and disabilities and the poor return in yields, but is still irresistibly drawn to it.29

As early as the middle of 1911 unrest amongst the men of the RAN had become a regular feature in the Australian print media. Deferred pay was seen as a major concern. Deferred pay was included in the gross salary figure and taxed accordingly but was withheld until completion of service. Sailors found the pension plan confusing and believed discharges on certain grounds would result in loss of entitlement. Naval administrators countered with the statement that no man would lose his deferred pay unless he was discharged due to ‘very severe’ misconduct. Rather than being discontent with naval management, RAN authorities declared sailors were leaving because all were in their ‘mature’ years and no longer enjoyed a life at sea.30 But the complaints continued. Another persistent allegation was that non-colonial ratings were being shown preference over those trained in Australia. The rapid promotion promises made to Australian volunteers in the first recruiting booklet had, it seemed, largely not eventuated.

The deteriorating situation resulted in the Acting Minister for Defence, Senator Gregor McGregor, releasing a lengthy statement. He denounced the men’s grievances as groundless. He explained that RN personnel were being promoted over RAN personnel because they were better qualified. On the subject of lower deck wages he noted that while a sailor’s pay was not as high as that obtainable in civilian life, a sailor’s salary was more ‘sure’. At the same time McGregor conceded that 34 men from Yarra and 12 sailors from Parramatta had requested discharges but this was due to misplaced anxiety and apprehension concerning prospects.31

Clearly the Acting Minister’s assurances had little success in generating confidence within the RAN lower deck because James Matthews, the Labor Member for Melbourne Ports, received 107 separate complaints from RAN volunteers.32 These again included the allegation that preferential treatment and additional allowances continued to be given to RN personnel. It is possible that the Australian-born ratings could have misunderstood that the additional salary granted RN personnel brought RN rates of pay in line with those of the RAN. Acting on Admiralty advice the RAN also accepted retired RN officers or senior ratings. Their salaries were paid by the RAN, supplementing their RN pensions. Victorian Labor politician, James Fenton, listed salaries as a major concern of Australian-born sailors, particularly this type of disparity; ‘men who do some of the most important work lower down the ladder’, he believed, were not ‘being listened to’.33

The Member for the Geelong seat of Corio, Labor’s Alfred Ozanne, believed an issue even more basic to life lay at the centre of much of the men’s discontent – namely food. Men onboard Yarra and Parramatta received a breakfast of porridge and bread and butter; a lunch of roast meat and potatoes with no other vegetables, and pudding only twice a week; and in the evening bread and butter and tea.34 As only the seafarers of the military forces would understand, food was critical to the contentment of a crew. The Naval Board had implemented a two-system general messing arrangement. In some ships a system of individual messing existed, whereby each seaman messdeck purchased and prepared food for its members. In other ships a system of general messing was used, whereby the food for the entire ship’s company was prepared by trained cooks. The RAN victualling system, unlike the RN system, was based entirely on a cash allowance whereby each man was allotted a daily victualling allowance. With regards to general messing, the victualling allowance was paid to the ship’s accountant or paymaster officer. The Admiralty was highly critical and argued for standard messing because otherwise it would encourage unrealistic expectations concerning the quantity and quality of food.35 But the successful implementation of the system of general messing also depended on the calibre of the ship’s accountant officer and the time and trouble he expended on messing duties for sailors.

During 1913 Staff Paymaster Hoare of HMAS Encounter was enthusiastic in his duties and his menus were varied and the food nourishing. Breakfast consisted of porridge plus a meat dish – pressed beef, mutton chops or sausages with mashed potatoes. Fish was offered one morning. Lunch, traditionally the large meal of the day, was normally a roast meat with two vegetables, or beef pies. Two or three days, syrup or plum pudding (‘duff’) was offered. Supper provided the largest variety – from dry hash, to tripe and onions or two pigs’ trotters or curried mutton or cheese and pickles. In addition the standard ration for each man per day was one quarter of a pint of milk, two ounces of butter, two ounces of jam, one pound of bread, five ounces of sugar and three-quarters of an ounce of tea. Encounter’s Paymaster did advise the ship’s company however that the menu would remain ‘subject to circumstances and money allowance permitting’. Encounter’s Commanding Officer, Captain B.M. Chambers, RN, supported Hoare in his efforts and advised the Naval Board on 29 November 1913 of the need for more highly trained cooks and better galley facilities. There were only minor disciplinary problems on his ship and he urged ‘prompt enquiry’, arguing that messing arrangements would not work ‘unless good cooks can be obtained’ and unless their ‘conditions of service’ were ‘attractive enough to secure competent men’.36 Within four months of this communication the Commanding Officer of HMAS Pioneer advised the Naval Board his cooks were deserting, due to their discontent with the system of general messing and because his ship’s galley was obsolete and totally unsuitable.37

Not all ship Paymaster Officers were as sympathetic or as capable of cheap and effective victualling as Paymaster Hoare and the victualling allowance was spent unwisely and food became scarce. Ships travelling in convoy could have victualling of entirely different quality. Successful messing of the men of the RAN also depended on the integrity of senior naval administrators. Complaints from the ship’s company HMAS Sydney were brought to the attention of the Australian Parliament during October 1913 by Labor Member for the NSW division of Dalley, Robert Howe. Howe explained that although the victualling allowance for each man was 1/4d a day he had heard that only 4d per man per day had been spent during the ship’s trip to Australia from England. This had left naval administrators with a saving of £200, whilst it was alleged the men of Sydney had been fed foul meat, contaminated tinned sardines and margarine instead of butter.38

Those in charge of the RAN chose not to address the conditions of service, instead they again attempted to curb unrest with selective discharges and increased discipline. Again sailors who had transferred from the colonial naval forces were seen as the ringleaders and the Admiralty ordered the RAN hierarchy ‘to get rid of those men at once, and not let them poison the minds of the RAN ratings’.39 Rewards for the arrest of stragglers and deserters were offered to law enforcement agencies. Mayors and civic functionaries were invited to deal severely with Australian ratings misbehaving onshore and it was decided that disruptive Australian Boy Seamen would be caned.40

The highly tattooed 18-year-old Victorian Ordinary Seaman Jack Jarman (1138) had been posted to HMAS Parramatta on 17 July 1911 and was promoted to Able Seaman on 1 August. The unhappy ship situation was difficult but the situation at home was worse and Jack was struggling with his conscience. His stepfather had had a stroke and was unable to work. The family income was reduced to a pension of 10/- per week. Mother Elizabeth was also in poor health; her first husband had died when her children were small and now her second husband was an invalid. Jack believed his family needed to take priority and he should be home to assist financially and physically, but to buy his way out of the RAN required a payment of £10 and a guaranteed wage of between £3 and £5 a week. The family simply did not have £10. On 21 November 1911 Able Seaman Jack Jarman, RAN, deserted.

Robert Smail (1068) was onboard Yarra at the height of the discontent. As a new Petty Officer he was in charge of sailors and required to ensure discipline and adherence to Admiralty orders at the junior level. It was a difficult time. He was 20 when he entered the RAN, signing on for a five-year engagement. He was diligent and hard-working and this was acknowledged with favourable reports and promotion. And now he was on the destroyer Yarra in a new navy trying to establish an identity. The Yarra ship’s company was caught up in public conflict when men like Smail simply wanted to do the job they had been trained for. It is not known if the unrest on Yarra influenced his career decision – clearly he wished to remain a navy man because he signed on for a further seven years on 1 July 1912, but he had chosen to move away from surface ships and on 1 July 1912 he was drafted to the London depot for submarine AE1.

The problems with Australian-born sailors were obscured in the Australian Parliament as Members of the new Liberal Government took up residence on benches previously held by Labor politicians, and naval disagreement of a different kind dominated debate. The Naval Board of the era was described by one writer as ‘an ill-assorted quartet, with widely differing backgrounds’.41 By 1913 friction within the Naval Board, particularly between the Second Naval Member, Captain Constantine Henry Hughes-Onslow, RN, and the Finance, Civil Member and Naval Secretary, Paymaster-in-Chief (later Paymaster Rear-Admiral Sir) Henry Wilfred Eldon Manisty, RN, was disrupting naval administration.

Manisty had been loaned to the Royal Australian Navy by the Admiralty for the period 1911 to 1914. In August Manisty wrote to the new Minister for Defence, Senator Edward Millen, of his antagonism with Captain Hughes-Onslow.

I do not feel that I can carry out satisfactorily the responsible duties that my present appointment entails while my conduct and actions are being attacked from the flank and the rear as shown in the minutes of my colleague and my subordinate.42

The two Naval Board members had little in common and had clashed often, but it was on the issue of the messing for RAN sailors that their differences of opinion could not be conciliated. Manisty had been the instigator behind the method of general messing implemented. Hughes-Onslow argued that not only was there no effective check against dishonesty and fraud but that the victualling of the men was dependent on the ‘caprice nature of the Accountant Officer’.43 In September the Minister for Defence informed Parliament that the internal relationship of the Naval Board had been unsatisfactory for some time.44 According to The Age ‘it is common knowledge that’ members had not been ‘on speaking terms for a considerable time’.45 The Minister had taken the decision to suspend Hughes-Onslow who asserted this was because:

I would not connive in defrauding the personnel, so as to curry favour with the Minister and enable the estimates to be cut down.46

There was also friction between Rear Admiral Creswell and Engineer Captain William Clarkson (later vice Admiral Sir). Although both men had served in the South Australian naval force their positions and responsibilities on the Naval Board resulted in serious disagreement. Punch referred to Creswell as ‘a great man’ but had strong reservations concerning his knowledge of modern navies: ‘Creswell learned his naval science 40 years ago’.47 The antipathy within the Naval Board monopolised government attention during the last months of 1913 when the subject was raised 15 times. From the floor of the House of Representatives the Member for Melbourne Ports, James Matthews, called for further Naval Board sackings:

It would have been better if the government, instead of suspending one man had suspended the whole crowd of them until some improvement was made.48

By November 1913 the Minister had admitted that the situation within the Naval Board had further deteriorated, that ‘harmonious relations’ were entirely absent, and the board so marred by personal friction and hostility that members were no longer on speaking terms.49 In his opinion the Naval Board was in a state of paralysis and this was seriously jeopardising the administration of the Department of the Navy. His Liberal Party Government favoured retiring Rear Admiral Creswell and having two more Admirals sent by the Admiralty to assume control.50 But regardless of the internal conflict and bureaucratic confusion, in October 1913 there was cause for great celebration. With great pride Australians welcomed their naval fleet for the first time, albeit minus two small submarines.

FOOTNOTES

1 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXI, 9 November 1911, p. 5947.

2 How to Join the Royal Australian Navy, Australian Navy Office, Melbourne, 1912, p. 16.

3 The Argus, 25 July 1911. Although the word ‘musketry’ was used it is unlikely muskets were still used.

4 ‘Kit’ was the name of uniform issue. For a new recruit in 1911 it commonly consisted of two blue serge suits, one white duck suit, two flannels, one silk handkerchief, collar, two white caps, one straw hat, two cap ribbons, two lanyards and one knife.

5 How to Join the Royal Australian Navy, p. 24.

6 The Bendigo Advertiser, 21 September 1914.

7 How to Join the Royal Australian Navy, p. 24.

8 Ibid., p. 28.

9 Ibid., p. 31.

10 The Argus, 17 March 1911.

11 The Argus, 18 January 1911.

12 The Argus, 12 July 1911.

13 MacAndie, p. 279.

14 Ibid.

15 Jones, p.134.

16 Commonwealth Year Book, Vol. 12, 1919, p. 1015.

17 Ibid.

18 The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1913.

19 ‘HMAS Tingira box’, HMAS Cerberus Museum, Victoria, letter written from HMAS Tingira, dated 22nd (no month) 1913 and signed ‘Russell’.

20 Phillipson, D. Band of Brothers, Sutton, Cornwall, 1996, p. x.

21 Wilson, R. Memoirs, PR84/26, Australian War Memorial.

22 Lind, J. HMAS Parramatta, 1910–1928, Naval Historical Society of Australia, Garden Island, 1974, p. 10.

23 How to Join the Royal Australian Navy, p. 24.

24 Batt, L. Pioneers of the Australian Navy, self-published, NSW, 1967, p. 40.

25 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXI, 13 October 1911, p. 1402.

26 Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March 1910.

27 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LX, 13 September 1911, p. 369.

28 Ibid., p.1402.

29 The Argus, 25 February 1911.

30 The Argus, 30 June 1911.

31 The Argus, 12 July 1911.

32 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXIX, 12 December 1912, p. 6956.

33 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXIX, 17 December 1912, p. 7267.

34 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXIV, 20 June 1912, p. 61.

35 MP1049/1, 1913/0408, National Archives, Victoria,

36 MP472/1, 13/13/5103, National Archives, Melbourne.

37 MP1049/1, 1918/0623, National Archives, Melbourne.

38 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXX1, 24 October 1913, pp. 2,520–21.

39 King-Hall, entry, 8 June 1913.

40 A 2585, Naval Board Minutes, 1904–1919, Nos 4–10, 4 March 1914, National Archives, Canberra.

41 Hyslop, R. Australian Naval Administration, 1900–1939, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1973, p. 45.

42 MP1049/1, 1913/0408, National Archives, Melbourne.

43 Ibid.

44 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXXII, 20 November 1913, pp. 3334–35.

45 The Age, 2 October 1913.

46 Hughes-Onslow, C. Capt. The Australian Naval Board Scandal, Melbourne, (sn), 1914,

p. 5. Manisty would return to Britain 1914 and retired as Rear Admiral Sir Eldon Manisty, KCB., CMG. Hughes-Onslow established a relief fund for sailors in distress, in Hyslop, R. Australian Naval Administration, p. 120.

47 Punch, 29 June 1911.

48 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXXI, 2 October 1913, p. 1809.

49 Ibid., Vol. LXXII, 20 November 1913, p. 3335.

50 Ibid., Vol. LXXI, 30 October 1913, p. 2665.