‘It is difficult to understand how the submarine would play any effective part.’

Captain William Creswell

In Australia elaborate plans were made to welcome the Royal Australian Navy fleet. The depth of the public sentiment would surprise officers and men; few anticipated the public celebrations that awaited them or expected that in little more than a year they would be involved in a world war. None could imagine the duties they would be called upon to undertake and the physical and emotional trauma which would ensue.

It was usual for Australians in the RN Australian Squadron to serve on HMS Challenger and HMS Pioneer (transferred to ACNB control on 1 March 1913). A ship’s complement is closely bonded, because unlike a land-based military detachment, a ship is a home, more than simply a place of duty. Though sailors formed closest friendships with others at their duty station, work space, or mess deck, loyalty to a specific ship could even override loyalty to the navy itself. Leading Stokers John Moloney (7200) and Charles Wright (7395) and Stoker Percy Wilson (7182), would have been well acquainted because they served onboard Challenger.

Also onboard Challenger, though separated in rank, ERA James Fettes (7290) would have been known to them, also Able Seaman Ernest A. Gwynne (7475), Boy Seaman 2nd Class Reuben J. E. Mitchell (7476) and Able Seaman John Reardon. They were all different in character, from different backgrounds, and motivated by different reasons to enlist and, in the case of Able Seaman John Reardon, of different nationality.

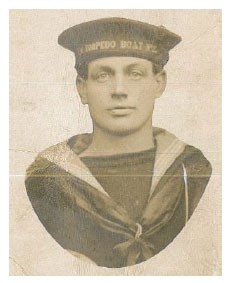

John Reardon was born on 9 February 1891, the third son of Edward and Catherine Reardon of Kaikoura, New Zealand. Four years later Edward died leaving Catherine to raise four young children alone.1 Known as ‘Rosy’ because of his very rosy cheeks, John left school at 15, intent on helping the family economy, but employment was scarce. He noticed a newspaper advertisement calling for naval volunteers to serve on HMS Pioneer.2 This offered adventure, training, and on completion of five years’ service, the sum of £250.3 This was a princely sum which would not only assist the family but set John up in his own home, business or farm. John survived the severely testing years of Boy Seaman training and with 13 others was posted to the cruiser HMS Challenger on 6 February 1911.4 By the time Challenger departed in June 1912 from Sydney for England the crew was full of Australasians excitedly looking to become part of the Royal Australian Navy and their fleet of new ships.

John Reardon had lost his father at too early an age, but for shipmate Stoker Percy Wilson childhood had been even more tragic. In 1881 the future looked bright for Adelaide Eldridge when she married Peter Wilson in Sydney. Her family had been Bankstown pioneers and now she and Peter set off on their own pioneering adventure to northern New South Wales. Peter was somewhat exotic being an Icelander – when few in Australia could place Iceland on a world map. The young married couple forged a life for themselves on 40 acres at Byron Creek which would later be known as Bangalow, and four girls and three boys were born between 1883 and 1893. Life for Adelaide was particularly difficult, struggling to care for seven children, cut off from civilisation and the support of her family. After the birth of her seventh child Adelaide fell into depression, the origins of which can only be speculated. Perhaps it was due to the death of a child, the care of six children under 10 years with little support, a disintegrating marital relationship or what we now know as post-natal depression. Whatever the reason, Adelaide poured kerosene over herself, and ignited the flame before finally throwing herself into the ocean. She was pulled from the water by a neighbour but died an agonising death. Peter Wilson abandoned his children – the youngest William, just four months old. The children were raised by Adelaide’s brothers and sisters.

The eldest son, Percy Lawrence Wilson, was born on 9 August 1889. Percy joined the navy as soon as he could and by the time he signed on the RAN dotted line for five years he was due for his first conduct chevron and sporting an anchor, heart and female tattooed on his right arm and a dagger and scroll with the words ‘Death before dishonour’ on his left. Percy Wilson (7182) was probably one of those ANF Stoker ratings frowned on by RN officers onboard Challenger because his initial report listed him as only ‘satisfactory’. A change to submarines resulted in the higher rating of ‘Superior’ repeated on his service card; Percy had clearly found his niche.

It was a remarkable experience for the Australasians of the Pacific fleet to sail into Portsmouth, England. Portsmouth was the most legendary of British navy ports and steeped in history. As sailors peered through the mists and light rain they could but marvel at the formidable fleet of warships anchored and moored, and shake their heads with disbelief that they were actually here in this hallowed place. Memorabilia remained from the Spithead naval review in July 1912, a poster declaring: ‘What Foe Would Dare To Invade Our Land With This Mighty Fleet to Guard It’.5 At the same time they knew a priority was to keep their own nations, half a continent away, protected. Again mixed loyalties and emotions were not helped by the obvious continuing division of opinion between Australian and British authorities.

The pride of the new Australian Navy was HMAS Australia. Built at John Brown Shipyard, Clyde-bank, Glasgow, Scotland, the Indefatigable Class cruiser had cost the Australian people the substantial sum of £1,705,000. Launched on 25 October 1911 by Lady Reid, wife of Sir George Reid, former Australian Prime Minister and now Australian High Commissioner in London, the battle cruiser was commissioned at Portsmouth on 21 June 1913. Examination of Australia’s 5-inch thick ship’s book reveals enormous detail but just three pages are devoted to the 820 officers and men needed to crew the 17,055 ton warship. The emphasis on nuts and bolts continued a naval tradition of taking personnel almost for granted. British shipbuilders incorporated the latest engineering and armaments but again living conditions were addressed almost as an afterthought. Whereas ‘other modernised navies … provided their crews with decent, tolerably comfortable accommodation’6, as British warships became larger the living spaces did not. The men who served on the heavy-calibre gun, steam turbine cruisers which symbolised the naval arms race between Germany and Britain in the first decade of the 20th century were almost as cramped as Nelson’s sailors on the Victory, a ship a third of the size.7 This was evident in HMAS Australia. Just 14 inches was allowed each man to swing his hammock; these were slung above spaces used for meals and recreation. No attempt was made to improve ventilation to ‘fetid, condensation-dripping messdecks’.8

At Portsmouth on 21 June 1913 Sir George Reid addressed the crew of HMAS Australia. In the presence of King George V he declared Australians were starting their fleet not because they were ‘Colonials’ but because they were ‘Britishers’. Applause erupted when Reid announced that 47 per cent of those gathered were Australians. Reid was mistaken, only 25 per cent were Australian. While 47 per cent were technically members of the RAN 22 per cent were ex-members of the RN and RN loan personnel. Reid did not see that this had the potential to create problems because the whole crew were British stock:

Whether English, Scotch [sic], Irish or Australians they all belonged to the grand old breed which had so well stood the test of time … Possibly Australia might be able to do without the Admiralty someday, but she had sense enough to know that she could not do so at present.9

The crew of the flagship typified the mix of RAN ratings. Only 1,660 of the 3,400 RAN force had been recruited in Australia. Very few Australians held places of authority. Captain Stephen H. Radcliffe, RN, assumed command of the Australian flagship. Onboard also was Rear Admiral George Edwin Patey, MVO (later Vice Admiral Sir George Patey, KCMG, KCVO), whom the Admiralty had selected to command the Australian fleet. As HMAS Australia departed England on 25 July 1913 the ‘who is in charge?’ and ‘whose navy is this?’ misunderstandings were self-evident. From the average British citizen to those who resided in the Houses of Parliament, the attitude was that Australia belonged ‘at home’, in British waters.10 The Evening Standard simply referred to the warship as ‘HMS Australia’11 and The Daily Mail alleged nine out of every 10 Englishmen believed Australia bore the prefix HMS.12

Debate between the Admiralty and the Australian Government over the stationing of the battle cruiser had commenced shortly after its launch. That the New Zealand funded Indefatigable Class battle cruiser New Zealand was commissioned ‘HMS’ and had been retained in British waters, had led to this debate. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, lamented that it was unlikely, however, that the Australian Government could be convinced to do the same.13 His representative in Australia persisted and in June 1913 Admiral King-Hall again made the suggestion to another Australian Prime Minister of ‘Australia being sent home if necessary’.14 Australian High Commissioner Reid continued to assert that whilst his country was attempting to consolidate its naval forces, it did so as part of the naval forces of the British Empire. Some English newspapers took exception to some of their Australian counterparts suggesting that the role of this ‘faster small naval force in the world’ should be local in nature.15 The British media believed that ‘every influence will be exerted to prevent the ships leaving Australian waters’.16 Furthermore it appeared to the English press that different training methods would be developed and Australian naval officers would adapt strategy and tactics to local conditions. The Daily Graphic cautioned against too much nationalism:

If ever the British Empire should be engaged in a great wild struggle the Australian people must have the wisdom to see that their ultimate safety would best be assured by sending the King’s Australian ships to line up with other ships of the King.17

The comment was a reasonable one as Australia was unlikely to be able to defend its interests. There was however validity in the suggestion that there may be a need to adapt strategy and tactics to the Southern Hemisphere and that British emphasis and maritime ideology needed to evolve.

Reports of the commissioning ceremony in Dublin’s The Irish Times and Scotland’s Dundee Courier contained an item not included in the English press. After ceremonial cheers were raised for the official party an Australian rating perched astride one of Australia’s 12-inch guns and shouted ‘Three Cheers for Wallaby Land’.18 Control and maritime strategy may have been paramount in the minds of RN officers with uniforms heavy with gold, and men residing on the benches of Australia’s Parliament; for Australians onboard their flagship it was that they were on their way home.

The ship’s company of HMAS Australia revealed the impressive array of skills and trades needed to man such a large and modern warship. Categories included: Seaman, Gunner, Boatswain, Signalman, Yeoman, Telegraphist, Sail Maker, Artificer, Mechanician, Stoker, Carpenter, Shipwright, Blacksmith, Plumber, Painter, Cooper, Armourer, Electrician, Sick Berth Steward, Sick Berth Attendant, Paymaster, Clark, Writer, Stewart, Steward Assistant, Ship’s Cook, Master At Arms, Ship’s Corporal, Band Corporal, Ship’s Musician, Officer Stewart, Officer Cook, Butcher, Lamptrimmer, Physical Instructor, Coxswain, Printer and Diver. The reluctance on the part of the Admiralty to encourage the RAN to attain any sense of naval autonomy was reflected in Australia’s documentation. Instructions concerning crew were highlighted in the heavy block letters: ‘NO DEVIATION IS TO BE MADE WITHOUT SPECIAL ADMIRALTY SANCTION’.

On 21 July 1913 HMAS Australia left Portsmouth, escorted by the new Town Class 5,400 ton light cruiser HMAS Sydney which had been commissioned on 26 June 1913 under the command of Captain John Collins Taswell Glossop, RN (later RAN and Vice Admiral, CB) and with a crew of 376. By the time Sydney entered the harbour of the city whose name she bore the cruiser had sailed 15,447 miles and burned 5,005 tons of coal. Australia and Sydney rendezvoused in Jervis Bay with the second Town Class light cruiser HMAS Melbourne. Commissioned at Birkenhead, England, on 18 January 1913 under the command of Captain Mortimer L’Estrange Silver, RN (later Vice Admiral, RN), Melbourne completed her delivery voyage from England at Fremantle on 10 March 1913. Also in Jervis Bay, preparing, were Encounter, Warrego, Parramatta and Yarra. For the grand entrance ratings were set to cleaning, painting and polishing. Members of the lower deck were not amused:

Now began a Navy ritual which lasted two days. Although the ships had steamed halfway round the world they must enter Sydney harbour looking like they left John Brown’s shipyard on the Clyde. Not a speck of rust must be left to offend the eyes of the Sydney’s shareholders in the fleet. Several tons of paint must have been used in the orgy of painting.19

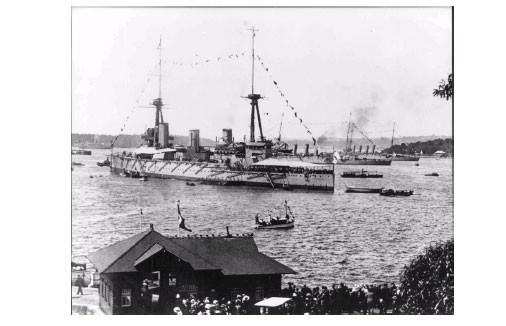

The Australian fleet entered Sydney Harbour on Saturday 4 October 1913. Large crowds had gathered along harbourside vantage points to wave and cheer as the warships secured to their buoys. One rating described how the welcoming crowds went ‘mad with delight’.20

The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

From the morning mist the long grey line came in … we were conscious of the pride of ownership … it was Australia’s fleet in being … thus as Australia played her part as a daughter of the homeland. Here is her contribution to the naval defence of the Empire … a separate Navy and yet attached to the Royal Navy.21

The Sydney Mail produced a special supplement to honour the grand entry and believed the fleet represented ‘Australian patriotism a love of country and the Empire’.22

A member of the Australian Naval Board declared:

It was a great occasion … a wonderful scene. Crowds had gathered from early dawn to every viewpoint round the harbour. There was much excitement, much enthusiasm.23

Political grandiloquence claimed credit for both parties. Leader of the Opposition Andrew Fisher observed: ‘The thing is done, and now there is no turning back’.24 Prime Minister Joseph Cook indicated his government’s naval policy in the following way:

The coming of our Australian fleet marks a place in the naval history of the Empire … A definite place has already been assigned in the scheme of Imperial defence. It is the Australian section of the Imperial Fleet.25

The Minister for Defence, Senator Edward Millen, adopted a more nationalistic approach in his speech, announcing that the arrival of the fleet marked the coming of age of the country. The future would severely test his words and belief that the fleet represented Australia and was resolved to pursuing national ideals and that ‘the fleet was the harbinger of peace not an instrument of war’.26

Again emphasis was expressed differently by opposing groups. In commemorative posters and books the youthful Australia was surrounded by Australiana while others portrayed the more traditional imperial image. Perhaps the most expressive description was that of one Sydneysider whose letter, signed ‘K. Bondietti, Alexandra Street, Hunters Hill’, appeared in The Catholic Press of

13 November 1913.

Rising like a phantom out of the sun-kissed sea it was first sighted from Hornsby Lighthouse at South Head, at 9.30 a.m. But while the black smoke of the cruisers curled heaven ward like fantastic snakes, it was not till 10.30 a.m. that it passed the Heads. ‘Here is our fleet’, was the cry that went, from mouth to mouth, and echoed from hill to hill; and ‘cheer upon cheer’ accompanied the fleet’s maiden entry into her home port. But while humanity was welcoming the fleet from ‘terra-firma’ more humanity — uncounted thousands — filled the little motor launches, sailing-boats and excursion steamers, waiting till the time would come when they could welcome at close range the fleet which means so much to Australia. Why all this enthusiasm? What use are all these engines of destruction to our fair morning land ... Well, an armed man is looked upon with fear by his adversaries. Australia armed means to make China and Japan think twice before they dare to attack her. The arrival of the fleet was a great day for Australia.27

The city of Sydney was decorated in a profusion of colour, with flags and shields bearing nautical symbols and the names of the ships. The fleet was dressed for the occasion and at night illuminated. Combined with the shore illuminations it made for a ‘pretty and pleasing spectacle’.28 Ships stayed for five weeks before sailing to other Australian ports. On entry to waters off Hobart it was difficult to secure safe anchorage. Warships were surrounded by a large flotilla of small sailing boats and yachts crowded with citizens anxious to demonstrate Tasmanian hospitality. By 1 February the fleet had anchored off the Glenelg wharf near Adelaide. Ships lifeboats struggled to carry the vast numbers of members of the public who wished to visit. An estimated 2,000 people had filled the wharf to overflowing. Signalman John Seabrook amused himself with the observation that as non-seafarers travelled the distance to the anchored fleet ‘a good many of the young ladies felt a trifle queer about the abdomen’.29

The Australian people had demonstrated a resounding enthusiasm for their navy and the men were proud of their role. Nonetheless from the more radical to the more conservative media came cautionary comment. The Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, New South Wales) of 8 October 1913, while acknowledging:

no more important event has happened in Australia since the arrival of the first fleet in Sydney Harbor on the 26th January, 1788 … than the advent of the first Australian Fleet of warships … most beautiful harbor in the world;

it also commented that onboard the Australian flagship and now in charge of this Australian fleet was ‘Rear-Admiral Sir George Patey, K.C.V.U., who has never been in Sydney Harbour before’.30 The Sydney Morning Herald editorial of 11 October 1913 believed Australians should not forget the ‘greatness’ of Australia’s debt, ‘to those officers who carried on the local navy before it had acquired battleships or cruisers’. 31

Also acknowledged was that dissatisfaction continued within the lower deck of this new navy. Food continued an issue of concern. One rating told of a letter signed by a number of Australia sailors sent to the company Maconochies. It warned that if the company sold any more ‘herrings and tomato sauce’ to the ship’s paymaster the next time their ship was off the coast they ‘would knock hell out of their works for expecting the defenders of the empire to eat such dam [sic] stuff’.32 Whilst the story was related in jest the general messing on HMAS Australia was no laughing matter for those who endured it. The men believed their poor rations were due to a lack of concern for their welfare and possible embezzlement of funds by the RN officers concerned.

Seniority and rank remained a most important issue. Officers within the fleet included few RAN officers. It had long been the custom of Australians who wished to become British naval officers to travel to Britain for training, to serve on RN ships for many years, and to absorb traditional RN attitudes and conventions. If the training of RAN recruits had progressed slowly the training of young Australians to assume officer rank within Australia was even slower. The Advertiser (Adelaide, South Australia) of 5 June 1912 described the ‘long-drawn-out negotiation’ which had been further delayed for another 15 months – regarding the completion of a naval college at Jervis Bay – which meant the entry of RAN Cadet Midshipmen would not occur until November 1913.

As the scholastic terms begin in February or June we would therefore not begin with the first batch of naval cadets before February 1914.33

Because the age of entry for Cadet Midshipmen was 13 this would disqualify many of those who had already passed their qualifying examinations. The then Minister for Defence George Pearce had again wearied of the protracted delays caused by navy bureaucracy and announced that Osborne House, Geelong, would be an interim college, and it would be ready by December 1913. Construction of the main RAN college buildings at Jervis Bay were not completed until 1915; the first two entries of Cadet Midshipmen moved from Osborne House in February that year.

The first 28 RAN Cadet Midshipmen did not proceed to sea until 1917 with only six posted to Australian ships, the majority being sent to RN warships. By 1918 only 14 of 52 RAN Cadet Midshipman had served on RAN ships.34 Nine eventually completed submarine training in England.35

Australian-born sailors made up the bulk of those below the rank of Petty Officer. Many members of the lower deck took their careers and future advancement seriously. Promotion meant higher wages, often more interesting duties, and power of command over others. Selection for promotion was dependent on a minimum period of service with good conduct, further training and qualifications; and reports on sailors’ expertise and conduct were dependent on predominantly non-Australian officers. In the nascent RAN there were many vacancies, yet Australian ratings continued to allege that their officers were reluctant to recommend them for promotion, preferring RN loan or ex-RN personnel. The Brisbane, Queensland, Worker newspaper warned that the RAN was not the RN and should not be:

Let us treat the Navy in a practical business-like way, tucker the men better, guzzle the big guns less, and cut out a large slice of the present heroising nonsense.36

The Australian welcoming celebrations of 1913 had further highlighted demarcation between officer and sailor. Ratings observed ‘an orgy of dinners and dances’ held by the officers of their ships, whereas ‘the crew’s share in the festivities consisted of what they could scrounge after the numerous parties held onboard’.37 Whilst this was an exaggeration and officers largely subsidised these functions themselves, it was officers, not the men, whom statesmen and society feted. A grand reception in Sydney Town Hall was given to officers of the fleet in October whereas ratings received a lunch in a park.

It is unknown if the demarcation between officers and men, or the standard hierarchical, disciplined and routine life onboard surface ships, was the reason that some of those drafted to England to commission the fleet chose, instead, to volunteer for a totally different naval lifestyle, to serve on Australia’s first two submarines. Leading Stokers John Moloney (7200) and Charles Wright (7395), Stoker Percy Wilson (7182), ERA James Fettes (7290), Able Seaman Ernest A. Gwynne (7475), Boy Seaman 2nd Class Reuben J. E. Mitchell (7476) and Able Seaman John Reardon had all served onboard Challenger. They found themselves in Plymouth in September 1912, decided to volunteer for submarine service and were drafted to Pandora depot in Portsmouth for initial torpedo and mining training at HMS Vernon. They were soon joined by other Australians from Encounter and Pioneer, including Stokers Ernest Blake and John Bray, Melbourne-born Stoker William James Groves (7301) and Western Australian Charles George Suckling (2148), Leading Seaman Gordon Corbould and ERA John Messenger. Unlike on warships promotions were quickly achieved by former ANF men: Groves was promoted to Leading Stoker and John Moloney, William Waddilove and Henry James Elly Kinder (7244) were all promoted to Petty Officer Stoker. Gordon Corbould received further torpedo training and advanced to Petty Officer on 7 August 1913. Able Seaman Jack Jarman (1138) whose experiences on the unhappy HMAS Parramatta and family responsibilities had seen him desert in November 1911, turned himself into navy authorities in December 1912. By March 1913 he was in England training on submarines and his conduct report had changed to read ‘Very Good’.

The ‘father’ of the Australian Navy, Rear Admiral William Creswell, RAN, was not a supporter of submarines: ‘It is difficult to understand how the submarine would play any effective part’.38 His critics commented that this was because he was a man of his generation and was uncomfortable with the newest technology. Creswell’s reservations may well have been due to a lack of faith in the new technology but he also believed that the submarines were designed for operation in the North Sea and British home waters, conditions very much different to what they would face in the Pacific and Indian oceans. The Australian conditions were ‘most unfavourable to the employment of submarines outside the harbours’; even in calm weather Creswell believed ‘the chances of successfully attacking an enemy’s vessels at distance from port’ were ‘remote’. With limited budgets Creswell believed he needed to find the most effective naval force to protect Australia. The decision to invest in submarines was ultimately made by Australian Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, on the advice of the Admiralty. The future would test Creswell’s reservations concerning Australia’s first two submarines. (In August 1917, his son, Lieutenant Colin F. Creswell, died on active service in an RN submarine.39 Another son was killed on active service.)

Built by Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness, Lancashire, England, the ‘E Class’ submarine was the newest of the new. The first was launched on 9 November 1912. Those manufactured for the RAN were distinguished simply by an ‘A’ being placed in front of the ‘E’ on their bows. AE1 was boat 80 and AE2 was boat 81; each cost the Australian Government £105,415 ($160,000). AE1 was laid down on 14 November 1911, launched on 22 May 1913 and commissioned on 28 February 1914. AE2 was laid down on 10 February 1912, launched on 18 June 1913 and commissioned on 28 February 1914. Displacement: 660 tons surfaced, 800 tons dived; length: 181 feet (55 m) beam 22 feet 6 inches (6.86 m) at the extreme width of the saddle tanks. Draught was 12 feet 6 inches (3.81 m). Propulsion was by way of two 8 cylinder, in-line, non-reversing Vickers diesel engines, producing 1,750 horsepower each when surfaced, 550 when dived, with two battery-driven electric propulsion motors. The propulsion motors could also be re-configured to act as DC (decibels) charging shaft generators for the main batteries. The submarines had two shaftlines and propellers. Speed surfaced was 15 knots (28 km/h) on two shafts, 10.5 knots on one shaft and dived 10 knots (19 km/h) on two shafts. Surfaced the range was 3,225 nautical miles (5,973 km) at 10 knots (19km/h) or only 25 nautical miles (46 km) at 5 knots (9 km/h) dived. Full complement would be three officers and 32 men. Armament consisted of four 18-inch (457 mm) Whitehead torpedo tubes, one tube facing forward, one tube aft, two tubes amidships one facing out to either side. One torpedo reload was carried for each tube – a total of eight weapons onboard. Spare torpedos were carried above the tubes with warheads separated. Warheads carried a 320lb (145 kg) of TNT and torpedo propulsion allowed each to travel at 35 knots with a range of 2,500 yards (65 km/hour with 2.3 km range). Armament for the ‘E’ class submarine would be enhanced by the retrofitting of a 12 pounder deck gun on a retractable pneumatic/hydraulic mounting. Unfortunately this occurred later and for the English submarines only. The wisdom of the Australian Government purchasing two new class submarines manufactured for Northern Hemisphere operations was questionable; in addition there were inevitable inherent problems with any new class ship or boat which could not be quickly rectified by the manufacturer across the world. The lack of the 12 pounder gun on retractable mounting may also have proved crucial during 1914.

The message which appeared on the noticeboard at Portsmouth barracks calling for volunteers for two submarines currently under construction at Barrow-in-Furness for the Australian Navy proved an exciting prospect, not only for Australians there to man warships but also for some RN personnel or ex-RN – 28 volunteers quickly applied. The ‘severe medical examination’, the degree of physical fitness required, and detailed family health histories resulted in the rapid elimination of all but two.40 More volunteers appeared at Fort Blockhouse, the depot of English submarines, also known as HMS Dolphin, to undergo the six-month training course. Extra submarine clothing consisting of a thick woollen jersey and undergarments were issued to offset the cold winter conditions within a submarine. Also issued was a pair of sea boots a couple of sizes too large, ‘so one has a chance to kick them off if one should happen to fall overboard’. Sea training was conducted on ‘A’, ‘D’ and ‘E’ class submarines. For volunteers the initial impression on the ‘D’ class was a bewildering jumble of pipes, wheels and electrical equipment with hardly any room to move. Worse to come was their first submarine dive off the Isle of Wight. The boat appeared to go down at angles causing anxiety. Petty Officer Henry Kinder decided: ‘My hair seemed to be standing on end’ and at this time:

A lot of men’s enthusiasm for submarines evaporated on that trip and I would have willingly returned to general service again, as the sensation of diving for the first time especially when the boat is not under proper control, is not a pleasant one. I was not altogether pleased to have volunteered.41

An enticement to remain was the extra allowance called ‘Danger Money’ but commonly referred to as ‘Blood Money’ but the early submariners wondered if it was sufficient. How could you measure the hazards? Many submarines were lost during the time the Australians were in England, ‘accidents were frequent, as the submarines were practically still in the experimental stage and could not be relied upon’.42

An incident which again underlined the hazards occurred when D2 had dived to 22 feet (6.7 m) and the captain decided it was unnecessary to station a lookout man at the periscope whilst he was in the bow listening for an underwater signal. One of the crew became curious and took a peep through the periscope to see a warship bearing down on the submarine. Panic broke out and the tanks were put hard to blow and the helm swung to port with D2 surfacing quickly, virtually under the bows of the warship. The men held their breath as it seemed the battleship would crash through the thin hull of D2. Fortunately those on the battleship’s bridge caught sight of the rising periscope. The Australians thought it ironic that the ship which missed them only by swinging hard to starboard was HMAS Australia undertaking steering trials. In typically Australian fashion Kinder wrote:

It is not pleasant having a boat of 20,000 tons racing towards you and it seemed strange that it was to be our future flagship. We were not sorry when orders were given to return to harbour as a shock like that is enough for one day. 43

Submarine training was exciting and daunting at the same time. One of the aspects most disliked was shallow water diving. A helmet was carried for each submarine crew member. Should the submarine sink in shallow water the helmet might offer an opportunity to escape to the surface. Unfortunately this method of escape could only be used to depths of no more than 22 feet (6.7 m). The helmets had their own inherent dangers. Once the helmet was placed over the head a tubed container with raw caustic soda was broken to purify the air. Another tube was held in the mouth and the other acted as a helmet exhaust. Should the mouth tube become unfortunately dislodged the next breath taken was very poisonous gas. Also should spittle enter the breathing tube the caustic could light and burn – the escape mechanism could well be more deadly than the alternative. Should none of these malfunctions occur and the submariner manage to escape his doomed boat and bob to the surface, the helmet could be inflated to act as a type of lifebelt and the glass face mask section opened to permit fresh air. The helmets were not very successful and within a couple of years all but one helmet within the submarine was discarded. Its best use was to clear any valve or rope fouling the propellers, or:

If one had a bad cold, ten minutes breathing through the container would give great relief and often effect a cure.44

Clearly submarines and the equipment were still in experimental stages.

Australian volunteers were again reminded of the fear and precarious nature of life of the submariner during the second half of 1913. They were training on E Class submarines during annual manoeuvres with the home fleet. The night they put to sea a heavy gale was blowing and ‘things were lively’ whilst they were surface running. The smell of hot lubricating oil in the submarine’s hot close atmosphere did not improve the stomach queasiness. Henry Kinder ‘sincerely wished myself ashore … Every hour that passed my liking for submarines grew less’.45 Crews had not bathed for their 10 days at sea and when they were allowed to their wash water needed to be used by several men. A common alternative was oil on a piece of waste cotton. The duty was difficult, watches were two hours on and two off, the lack of sleep and constant manoeuvres with continuous engine troubles in rough weather meant ‘all the crew were fed up’. As E4 returned to Harwich Harbour the Admiral of the fleet requested that they repeatedly dive close to the flagship. The submarine captain felt he needed to follow this ‘request’ although he had been warned by engineering staff that the air pressure for blowing the water out of the tanks to bring the boat to the surface was low, as were the electric main motor batteries. On diving the third time E4 had difficulty returning to the surface; ‘it was hard to say if we were going up or down’.46 The submarine crew returned to port rather rattled, only to hear more alarming news. E5, launched just in May 1912, had suffered an explosion in the engine room killing six and severely burning the remainder of the crew – Australians were onboard.

In October 1913 crews were drafted to the Australian submarines at Barrow-in-Furness. For the following five months they learnt their boats from stem to stern. The submarines were divided vertically into three sections by two bulkheads fitted with watertight doors. The front section contained a bow torpedo tube, a reciprocating pump for emptying out the ballast tanks and motors for hauling in the anchors. Common practice was that one anchor could be let go whilst the submarine was on the bottom to prevent the boat from drifting. Around the torpedo tubes engine room stores and spare gear were stored with most bolted onto plates to prevent movement in rough weather. Accessing parts was likened to a ‘Chinese puzzle’. A wireless cabin was jammed up against the wardrobe, taking up a great deal of room because it needed to be soundproofed. It helped if the operator was of slight build so that he could wedge himself in. It quickly became apparent that the wireless was of limited use because of the amount of electrical equipment around it. The main motor and light switches were housed in the aft section. Close by were the two big hydroplane motors and a large brass wheel which operated them by hand. The hydroplanes, resembling fins, were fitted on the outside of the submarine, two in the bow and two in the stern; they were used to dive the boat. Atop of the hydroplane wheels were two large depth gauges indicating the depth of the boat when dived, to 120 feet (36.58m). These gauges also indicated, by way of curved spirit levels within, if the boat was level.

Two Coxswains were stationed at the hydroplanes to watch the spirit bubble and ensure the boat was kept level.

Beneath the conning tower were two periscopes better known as the ‘eyes of the submarine’ once the conning tower doors were closed. They were only of use at a dived depth of no more than 22 feet (6.7 metres). Should the boat go deeper it could be steered by compass and hopefully good judgement. On either side of the conning tower two large rotary pumps were capable of emptying 105 tons of water from the ballast tanks in just three minutes. Aft of the conning tower were the beam torpedo tubes. Further aft was the Chief’s and 1st Class Petty Officer’s mess with an electric oven and two small tables. There was no room in a submarine crew for a designated cook and Australian Petty Officer Stoker Henry Kinder bemoaned the fact that the individual designated to prepare meals ‘might have been a good signalman but in the culinary arts he was a hopeless failure’.47 Perhaps it was a blessing in disguise that no cooking was permitted once the submarine was dived.

Through the second bulkhead door was the engine room with its two large 8 cylinder diesel engines only used when the submarine was running on the surface, whereas the two main motors were used when dived or going astern. The engine fly wheels each weighed 2 ton. The clutch, which lay between the engines and main motors, allowed the main shaft to be broken to allow the motors to work the propeller independent of the engine. Further aft lay an air compressor used for fuelling air bottles and another clutch. The torpedoes required 3,000 lbs of air pressure to fire. Two clutches enabled the engine to drive the motor and charge the batteries without turning the propeller, or to drive the compressors without propeller or engine. When the engines were running, the noise was deafening and hand signals were the only way of communicating.

Every nook and tiny space was jammed with spare gear, spanners and the 48 air bottles which were kept pumped up to the 3,300 lbs pressure required to blow the water out of tanks when bringing the boat to the surface. Tanks at each end of the submarine were kept half full and connected by a pipe. Should the boat be unlevel water would be released from one tank to the other until the boat was on a level keel. Going ahead on main motors whilst turning the forward hydroplanes down to catch the water resistance, the bow of the boat would gradually be forced downwards. To achieve a level angle, the aft hydroplanes would be turned up to lift the stern and as the required depth was reached resistance was gradually removed off the planes. The planes were reversed and the main ballast tanks blown to surface.

Human habitability had received only minimal consideration. The three officers shared one bunk. A very cramped crew quarters on a platform over the main motors included an electric stove. Sailors ate and slept between torpedoes. Although smoking onboard was banned it took little time before the air became foul. Food tasted the same, flavoured with engine oil. The toilet (‘heads’ in naval jargon) was a bucket. Every piece of clothing was impregnated with that distinctive submariner scent. It was always a pleasant experience to remove oneself to the private lodgings at Barrow-in-Furness where the submariners were billeted, and to enjoy stretching the legs and breathing fresh air on weekends in the dockyard.

By January 1914 engine and diving trials were underway. The submarines faced trimming and inclining experiments in Devonshire Dock, Barrow-in-Furness. The boats were moored head and stern in choppy water with a stiff north-westerly wind blowing.

The trimming experiment on AE2 showed that all internal main ballast tanks could be filled. The trimming experiment on AE1 showed that all internal main ballast except ‘Y’ could be filled. The two boats should have been exactly the same. The difference in the boats in the two trimming experiments was explained away because AE1 was carrying a large amount of spare gear, which would ordinarily be carried on a depot ship. A second test without extra gear was never conducted though there was comment that if this was performed, ‘it may be possible to carry the whole internal tanks full’ – that was considered very desirable.

It is suggested therefore, that after arrival at Sydney, a second trimming experiment be carried out on AE1, the boat in service conditions, and if it be found that under such conditions it is impossible to fill the whole of the internal main ballast tanks, one or two of the cast trim blocks of the ballast keel should be removed, and the space filled in with wood.48

Shortly afterwards AE1 and AE2 were in Portsmouth, provisioning for the longest journey yet undertaken by submarines.

The RAN Representative in Britain was the Royal Navy’s Captain Francis Fitzgerald Haworth-Booth (later Rear-Admiral Sir Fitzgerald Haworth-Booth, KCMG), RN. Publically he was delighted as he ‘bade the crews of the Submarines farewell on behalf of the Government of Australia’. In Portsmouth he was assured by Commodore Keyes, RN, that not ‘one of the Submarines in the RN has such experienced crews as those in AE1 and AE2.

I was further informed that very special care in the selection of volunteers from the Royal Navy for service in the R.A.N was taken by Lieutenant Commander M.E. Naismith, RN of HMS Arrogant, tender to ‘Dolphin’.49

Certainly this statement would appear well justified as the majority of RN or ex-RN personnel boasted a wealth of experience. Several had followed the same career path.

Petty Officer Thomas Martin Guilbert (RN 208663, RAN 8279) was born on 25 November 1883 at St. Peter Port, Guernsey, in the Channel Islands, with a dash of French blood in his veins. He worked as a labourer until he joined the RN as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class at HMS Ganges on 11 January 1900, the notoriously challenging Boy Seamen establishment. After a draft to HMS Lion he was promoted to Boy Seaman 1st Class, followed by drafts to HM Ships Minotaur, Agincourt and Hannibal. On 25 November 1901 he was promoted to Ordinary Seaman, then on 5 May 1903 to Able Seaman (Torpedoman). At HMS Vernon (the torpedo and mining school) at Portsmouth he qualified as Seaman Torpedoman on 10 December 1904. Thomas Guilbert served on HMS Firequeen, until drafted to HMS Hogue for passage to the China Station, and joined the 6,400 ton twin-screw special torpedo vessel HMS Hecla in May 1905. On his return to England and HMS Vernon the following year he re-qualified as Seaman Torpedoman. Ensuing drafts were mainly to surface ships, and he would be a Petty Officer (3 November 1910) when again classified for submarines. He married Violet Victoria (nee Harckham), herself a member of a navy family, at St James, Portsmouth, in 1916 and soon added baby George to their family.50 It was probably the possibility of career advancement that led to Tom’s decision to volunteer to be ‘Lent to the RAN for three years’. Although designated ‘spare crew’, Petty Officer Thomas Guilbert assumed the position of Coxswain of AE1 during 1914.51

Petty Officer Henry Hodge (RN 196497, RAN 8260) was a colourful character. He had a peacock tattooed across his chest and butterflies and animals decorating both forearms. Born on 28 April 1881 in Preson, Lancashire, son of farmer Lawrence Hodge and Mary Anne Hodge (nee Beattie), like Guilbert he enlisted in the RN as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class, at HMS Northhampton on 17 November 1897. His general service time commenced on 17 November 1899 when he signed on for what must have seemed an eternity to an 18-year-old – 12 years. Drafts came in quick succession: Agincourt, Diadem, Pembroke I, Argonaut and Firequeen. On 4 May 1905 Able Seaman Hodge decided to volunteer for submarine training and was a Leading Seaman by 1 November 1909. Like Guilbert after five years he was required to return to surface ships and served with the RN 4th Cruiser Squadron and HMS Essex. The pull of submarines remained strong and he returned to re-qualify as Seaman Torpedoman as soon as he was permitted. Hodge received his third Good Conduct Badge on 5 December 1912 and was promoted to Petty Officer on 24 February the following year – the same year that he too was ‘Lent to the RAN for three years’.52

This must have been a difficult decision as it meant an extended time away from wife Ida Louise (nee Mead), and children three-year-old Henry Thomas and one-year-old Lawrence James. A similar discussion would have occurred in the home of fellow Petty Officer Tom Guilbert and his wife Violet, and in the home of Petty Officer William Tribe (RN 191329, RAN 8261) and his wife Kate. The three families lived in that most navy of cities, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. RN wives and their children needed to be resilient. They needed to survive long absences of husbands and fathers and sometimes the word ‘survive’ was the most appropriate. Non-navy families could never understand and often the only succour forthcoming was from other navy wives and families.

Petty Officer William Tribe left behind his wife Kate (nee Penney) whom he had married in 1908, and their three children: William born in 1909, Emily born in 1910 and baby Rose born in 1913. Petty Officer Tribe himself was born at Midhurst in Sussex, England, on 10 December 1880, the son of Ellen Spiers. Leaving school at an early age to assist his mother he worked as an errand boy. Enlistment in the RN as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class at HMS St. Vincent on 8 December 1896 offered so much more security, training, pay and conditions. He was promoted to Boy Seaman 1st Class in September 1897. His general service time of 12 years commenced on 10 December 1898 and he was drafted to HMS Pembroke I in 1898, then Agincourt and the 14,900 ton battleship HMS

Illustrious I. William may have decided smaller vessels were more to his liking because he volunteered for submarines. Promoted to Ordinary Seaman on 10 December 1898 and to Able Seaman on 1 February 1900 he was by then a Torpedoman. After serving as a Seaman Gunner during 1901 he joined HMS Vernon (the torpedo and mining school) at Portsmouth on 22 June 1902 and again in 1904 where he qualified as a Seaman Torpedoman in November that year and Leading Torpedo Operator the following year. William was back to Vernon in August 1907 to re-qualify. The posting to submarines physically occurred in November 1907. He was rated Leading Seaman on 24 May 1909. Promotion to Petty Officer occurred in August 1911. After five years’ submarine service William returned to general service, but the fascination for life beneath the waves remained and he re-qualified again as Leading Torpedo Operator in January 1913. The constant re-qualification throughout the lower ranks in the RN must have been burdensome and a significant disincentive. On 17 November 1913 Petty Officer William Tribe was ‘loaned to RAN for three years’ for submarine AE1.53

On the evening of 18 February 1914 the RAN Representative in Britain, Captain Francis Fitzgerald Haworth-Booth, RN, on behalf of the Australian Government, entertained all the officers of HMA Submarine Service at the Royal Naval Club, Portsmouth, including the Commodore of the Submarine Service, his assistant and the Commanding Officers of HM Ships Excellent and Vernon to thank them for the ‘invaluable help rendered by them to the Commonwealth’. The Commodore encouraged him to persuade the Australian Government to commit to the purchase of more submarines, ‘as soon as practicable’. It was his opinion that the Australian Government should make the commitment to purchase later class submarines as even the more recently manufactured E Class were superior to AE1 and AE2 and:

that the day is not far distant when submarines will be able to undertake many of the duties in the Fleet now performed by Destroyers.54

Haworth-Booth agreed with this advice and hoped the Australian Government would commit to the purchase of larger and more modern submarines because it was his ‘personal opinion’ that E Class boats ‘are just too small to be thoroughly efficient … for Fleet work and distance from Base’.55 The new submarines would probably cost in the vicinity of twice the price of AE1 and AE2.

Whilst impressed with the crews who prepared to take Australia’s first submarines home Haworth-Booth did voice privately to RAN authorities that he had serious concerns whether or not the submarines were quite mechanically ready for their long journey. The truth of his words would prove prophetic. He believed further tuning and special exercises were needed for a ‘few weeks longer’ as he expected that during the voyage there would be ‘minor breakdowns’ and the boats would arrive with ‘a considerable list of defects’, severely reducing the ‘the efficiency and value of the type of submarine’. This would mean they would be ‘hastily condemned’ by opponents within the surface ship hierarchy.56 This lack of preparedness for the task ahead did indeed prove dangerous for the crews of Australia’s first submarines.

FOOTNOTES

1 Wright, G. Kaikoura Submariner, self-published, New Zealand, 2014, p. 7.

2 Ibid., p. 8.

3 Ibid., p. 10.

4 Ibid., p. 54.

5 Postcard, Spithead Review 1912.

6 Phillipson, p. 29. This comment was made of an RN warship of the same class.

7 Keegan, J. Price of Admiralty, Hutchinson, London, 1988, p. 120.

8 Phillipson, p. 28.

9 MP178/2, 2310/14/129, National Archives, Victoria.

10 Parliamentary Debates, Vol. LXX, 12 August 1913, p. 63.

11 The Evening Standard, 30 June 1913. HMAS Australia Press Cuttings, HMAS Cerberus museum.

12 The Daily Mail, 30 June 1913, ‘HMAS Australia Press Cuttings’, HMAS Cerberus museum.

13 Lambert, Far Flung Lines, p. 71.

14 King-Hall, entry, 17 June 1913.

15 Manchester Guardian, 1 July 1913, HMAS Australia Press Cuttings.

16 Plymouth Western Morning News, 1 July 1913, HMAS Australia Press Cuttings.

17 The Daily Graphic, 1 July 1913, HMAS Australia Press Cuttings.

18 Dundee Courier, 2 July 1913 and The Irish Times, 2 July 1913, HMAS Australia Press Cuttings.

19 Batt, p. 65.

20 Seabrook, J.W. Papers.

21 The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 October 1913.

22 The Sydney Mail, 9 October 1913.

23 Ibid.

24 The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 October 1913.

25 To Commemorate the Arrival of the Australian Fleet, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1913.

26 Ibid.

27 The Catholic Press, 13 November 1913.

28 MacAndie, p. 288.

29 Seabrook, J.W. Diary, 1SRL669, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

30 The Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, New South Wales), 8 October 1913.

31 The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 October 1913.

32 Batt, p. 92.

33 The Advertiser, 5 June 1912.

34 Jose, A.W. Official History of the Royal Australian Navy, 1914-1918, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1928, pp. 475–476.

35 N.K.Calder, A.D. Conder, E.S. Cunningham, F.E. Getting, F.L. Larkins, J.B. Newman, C.A.R. Sadlier, H.A. Showers and L.S. Watkins.

36 The Worker, 23 October 1913.

37 Batt, p. 66.

38 Hyslop, R. ‘Creswell, Sir William Rooke (1852-1933), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 8, (MUP), 1981.

39 The Advertiser, 29 August 1917.

40 Kinder, Diary.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 AE1and AE2 Trimming and Inclining Experiements, To the Official Secretary for the Commonwealth of Australia’, CP03/14, Sea Power Centre, Canberra.

49 Naval Representative 55th General Report, London, 26 February 1914, MP1049/1, 1914/0132, National Archives Melbourne.

50 email Hazel Oliver, 3 September 2013.

51 The truly amazing research undertaken on the British officers and men was undertaken by Barrie Downer, ‘Submarine AE1 Crew List’, 4 November 2011. This book is much the richer for Barrie’s work.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid. and interview Tom Tribe, 7 October 2013.

54 ‘Naval Representative 55th General Report, London’, 26 February 1914, MP1049/1, 1914/0132, National Archives Melbourne.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.