‘Through a long list of mechanical difficulties and mishaps overcome by hook and crook, the miles were pushed astern’.

Stoker Charles George Suckling (RAN)

Unlike the pomp and circumstance exhibited during the commissioning of warships such as HMAS Australia the commissioning of AE1 and AE2 on 28 February 1914 was a very private affair. This was in part due to the secrecy involved with this arm of the navy, but it could not be denied that submarines were viewed with disfavour and even distrust by the greater part of those serving in the RN, particularly senior officers. The submariner saying: ‘There are two types of ships … submarines and targets’, would originate during this century but the degree of disfavour accorded submarines had been expressed in the words ‘underhand, unfair and damned un-English’ muttered by Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson VC, RN, who was appointed First Sea Lord in 1910.1

Lieutenant Commander Thomas Fleming Besant, RN, was given command of AE1 with Second Captain being Lieutenant Charles Lewis Moore, RN. AE2 command was awarded to Irishman Lieutenant Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker, RN, and his First Lieutenant was Lieutenant Geoffrey Arthur Gordon Haggard, RN.

Besant was born in Liverpool, England, on 22 December 1883, the son of Edgar and Mary Besant who afterwards settled in London. He joined as an RN Cadet Midshipman on 15 September 1898 and was promoted to Midshipman in May 1900. Besant saw service in the Boxer Rebellion and was promoted to Sub Lieutenant in May 1903, before deciding to specialise in the exciting new sphere of hydro-aeroplanes and submarines. A Freemason, Thomas Besant was appointed to HMS Thames for submarine training at the beginning of 1905. Nine months later he was in Devonport at HMS Forth and was promoted to Lieutenant on 31 December 1905. His rapid change of postings continued before being returned to HMS Thames for submarine ‘command’ and then back to Portsmouth by September 1906. In November 1907 he was in charge of submarine C12. The vagaries of navy postings saw this command last only eight months before he was returned to the surface fleet, to something much, much larger – the battleships HMS King Edward VII and Hercules. Besant’s next submarine appointment was submarine C30 on 15 August 1912. On 4 September 1913 he agreed to be ‘loaned’ to the RAN for three years, given command of Australia’s first submarine and the added submarine pay of 6/- per day and 3/9d per day for ‘command’. Besant added another half a stripe to his uniform with the promotion to Lieutenant Commander on 31 December 1913 and assumed command of the Australian Submarine Squadron.2 Whilst listing an interest in horses, golf and fishing, the Captain of AE1 was an intellectual with a broad taste in literature. Books on public speaking, the laws and practice of chess, Shakespeare, the works of Rabelais and Voltaire in French, texts on the motor car and engines, and The Death of Hiawatha, travelled with him on the submarine support ship.3

AE1 Second Captain, Lieutenant Charles Lewis Moore, RN, was a bachelor, like Besant, but that was where the similarities finished. Lieutenant Moore was more interested in sporting activities. He preferred golf, tennis, hockey, shooting and horse-riding to literature. Born in Dublin, Ireland, on 23 August 1888 into a military family, Moore was the younger son of Colonel (later Sir) Henry Moore of the King’s Own Royal Regiment, and Mrs Annie Sophia Ruthven Moore of Somerset. Charles was educated at Acreman Street prep school, Sherborne, Dorset, and later at Wellington College, Berkshire. He followed his elder brother Henry into the Royal Navy as a Cadet Midshipman through Britannia Royal Naval College (commonly known as Dartmouth) in 1904. On promotion to Midshipman on 15 May 1905 Moore was appointed to the 3rd Cruiser Squadron flagship HMS Leviathan on 15 May 1905. Promotion to Midshipman came on 30 July 1905 and in November 1906 he was posted to the commissioning crew of the cruiser Bacchante at Gibraltar. Moore was promoted to Sub Lieutenant in September 1908. In 1911 he decided to volunteer for submarine training. He was appointed to the submarine depot ship HMS Arrogant for submarines. Promoted to Lieutenant on 1 April 1913 he was re-appointed to Arrogant on 18 September 1913. Clearly attracted to the adventure of being a pioneer submariner travelling around the globe to a pioneering nation and its navy, Moore was ‘loaned’ to the RAN for a period of three years from 14 October 1913.

The submarines AE1 and AE2 left Portsmouth at 7am on Monday 2 March 1914 with their escort the light cruiser HMS Eclipse carrying personal belongings, spare crew and submarine ordnance. In charge of the small convoy was Captain F. Brandt, RN, a seasoned submarine service officer. Eclipse would be required to tow AE1 and AE2 during the voyage to allow maintenance time whilst undertow. The Admiralty had decided three days in each port would be sufficient. HMS Yarmouth would wait in Colombo to escort the submarines on the next leg of the journey. HMAS Sydney would act as the final escort to Australia from Singapore.

A mixture of emotions gripped the men. For all there was the excitement that accompanied the promise of adventure. For those now on loan from the RN there was the complete unknown. The anticipation for RN personnel was tempered by farewells. They would miss watching their children grow, not be present perhaps for the death and funeral of a close relative. And prolonged absences tested the best of navy marriages with the added strain on wives. It was always the same, the eagerness to go to sea and the yawning emotion of leaving. Those who could access the deck attempted to catch one last glimpse of England through the bleak and overcast morning. The Australians were going home, their relief and anticipation was palpable. Several had married English girls, like Stoker Petty Officers Henry Kinder, John Moloney and Stoker Percy Wilson, but they were aware that passage to Australia for their brides was imminent.

The crews were attempting a journey never before undertaken; they might make history or they could die. On 3 March the submarines entered the Bay of Biscay and ‘the steering gear jammed for a couple of minutes through loose pin in conning tower’ on AE2. Valve springs broke during the day on both submarines when proceeding to full speed. This was overcome by stopping the engine with the broken spring and shifting the spring. This could be accomplished in five minutes without ‘dropping much astern of station’. On 4 March, just three days out of Portsmouth, AE2 lost a blade off the port propeller causing so much vibration that it was deemed advisable to be taken into tow by Eclipse at 6pm.4

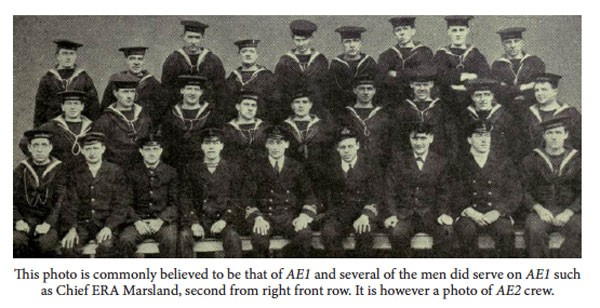

Henry James Elly Kinder (7244) was born in Sydney on 17 January 1891. He was a former ANF Leading Stoker and was promoted to Stoker Petty Officer on 11 February 1913 after arriving in England the previous year. He was drafted to join AE1 but after returning from leave to marry, he found himself drafted to AE2. Kinder was on watch when AE2 lost a propeller blade and it seemed to him ‘the boat would shake to pieces’.5 On arrival in Gibraltar on the afternoon of 6 March a diver was sent below to ascertain the extent of the damage. New chocks had to be cut into the dock so that the submarines could tie up. Two spare propellers were carried on board the escort for each boat, but at least one was found to be cracked due to faulty manufacturing. As the propeller was made out of one piece, a new one had to be fitted. Time was of the essence, and with the dock pumped dry by 2pm the damaged propeller was removed and a spare propeller fitted. By 8pm the dock was flooded, the submarine undocked at 10pm and sailed at 11pm. Chief ERA Marsland was justifiably proud of his work and of the other Artificers: ‘a smart piece of work for the time allotted … seeing there were keeps and plates to be fitted’.6 There was not even enough time to collect all their tools before the flood gates were opened. The engineering staff was allowed a brief sojourn to ‘replenish a thirst that had developed … good job finished’.7 The Artificers would argue they were the most important members of the crew, a claim continued through time by naval engineering officers and sailors. While seamen received much more public attention and status, those whose occupation ensured submarines and ships operated believed this was a misconception.

Artificers commonly entered the navy with a trade or some experience with machinery as was the case with Ballarat’s ERA John Messenger and Sydney’s James Fettes. They were joined on the Australian submarines by RN loan personnel including: Chief ERAs Thomas Frederick Lowe (RN 271421, RAN 8263), John Albert Marsland (RN 270573, RAN 8274) and Joseph William Wilson (RN 270296, RAN 8284).

Thomas Lowe had been promoted to Acting Chief ERA on 1 February 1914. Born on 3 December 1875, the son of John Thomas and Mary Elizabeth Lowe of Leicester, England, he was a fitter and turner when he enlisted in the RN as a direct entry. As Acting ERA 4th Class Lowe was drafted to HMS Firequeen II on 19 November 1903 and in July the following year he was drafted to the battleship HMS Hannibal. As an ERA 4th Class he was drafted to the protected cruiser HMS Gladiator and the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire during 1905, whilst by November the following year he was rated ERA 3rd Class. There were further drafts to battleships Barfleur and Renown, in 1907. It was this year he decided to join the submarine world, and was promoted to ERA 2nd Class in November 1910. Over the next two years Lowe moved between the 4th, 5th and 8th Submarine Flotillas before volunteering to be loaned to the RAN Submarine Service for three years from 17 November 1913.

John Marsland was a Yorkshire man, from Leeds. Born on 9 October 1880, the son of John and Annie Marsland, he trained as an engineer fitter before entering the RN as Acting ERA 4th Class at HMS Vivid II on 5 November 1901 for a 12-year engagement. He served on HM Ships Niobe and Vivid II, and the battleships Empress of India and Magnificent and the gunnery school at HMS Cambridge. By October 1904 Marsland had volunteered for submarines as an ERA 3rd Class, and was promoted to ERA 2nd Class in November 1908. Because submarine service was limited to five years, Marsland then returned to general service. He did his compulsory two years on the cruiser HMS Argyll and battleship HMS Implacable. But the preference for life as a submariner prevailed and Marsland returned on 17 August 1911 to HMS Thames, the submarine depot ship. On 3 November 1913 he volunteered for three years service with the fledging RAN submarine fleet of two. Wife Nellie Louise Griffiths Marsland, living in Southampton, Hampshire, wondered when she would next see her husband as the Australian Submarine Squadron left Portsmouth on 2 March 1914. Fortunately for Nellie, John enjoyed writing – and not just the odd letter – because he would kept a diary entitled: ‘13,000 miles in a Submarine in 83 days’ detailing an amazing nautical achievement. It was published in Sydney’s Sunday Times and would become a highly valued family possession.

Chief ERA Joseph Wilson was born in that most navy of places, Portsmouth, on 11 October 1879 – the son of J. H. and E. Wilson. He also entered the RN as a direct entry Acting ERA 4th Class having trained as an engine fitter, and joined HMS Duke of Wellington on 23 October 1900. Wilson was drafted to HMS Pyramus from February 1903, introducing him to Australian navy personnel. He served on HM Ships Duke of Wellington, Firequeen II and Victory II, being promoted ERA 4th Class on 2 January 1902. On 14 September 1905 he was drafted back to HMS Psyche on the Australia Station. He returned home in August 1907 when drafted to the cruiser HMS Crescent and to Victory II two months later. Joseph Wilson volunteered for submarines, was rated ERA 2nd Class on 23 October 1907 and continued his submarine training. Promotion to Acting Chief ERA 2nd Class followed on 23 June 1912 and he was drafted to HMS Dolphin on 31 August 1912. Confirmation to Chief ERA 2nd Class came on 23 June 1913. Wilson was tall at 5 feet 9 inches (175cm) and the word ‘dapper’ well described this brown-eyed, brown-haired intelligent man. His wife Elizabeth Jane Cecelia Wilson was a tailoress, so clearly she ensured his naval uniforms fitted perfectly. It was extremely rare for a member of the lower deck to receive higher than ‘Superior’ for ‘Ability’ on service reports, but Joseph Wilson was awarded ‘Excellent’ not once but twice. Clearly he was not deterred by Australian accents and mannerisms during his drafts to Australian Squadron HMS Psyche and Pyramus because he volunteered to be loaned to the RAN from December 1913. Joseph Wilson was not drafted to AE1 or AE2 but designated ‘spare crew’. When he waved goodbye to Elizabeth and their four children aged between nine and three, he probably believed he would advise and assist with the general maintenance of the submarine squadron. Unfortunately fate intervened and because of the shortage of engineering staff he was drafted to AE1.

Chief ERA John Marsland believed ‘any young man’ wishing ‘to see the world’ should join ‘our new Navy and also get along in life at the same time’. He extolled the virtues of hard work because, as he put it, he ‘should never have seen one quarter of the life I have seen’ had he remained a ‘Stay-at-Home Boy’8. Whilst being proud of how the engineering staff had handled the propeller blade replacement he already had concerns. ‘Though the engines had behaved admirably … a propeller can easily be damaged, should you foul any floating debris.’9 His cautionary note was proven correct.

On 6 March at 11pm the submarines were on their way to Malta. The Mediterranean, notorious for fluctuating weather patterns, was on its best behaviour and was beautifully calm. In spite of the wonderful conditions AE1 suffered malfunctions of the intake valve springs, exhaust, engine clutches and overheating of the motor shaft and bearings and the toggle bolts, and was taken into tow.

The submarines reached Malta at 9pm on 13 March and berthed alongside a receiving ship. Though the stay was to replenish oil and provisions, leave was allowed and it was a tremendous relief for the crew to stretch their legs after such cramped confines and to escape the all-too-familiar polluted air. John Marsland and ‘a couple of chums’ decided to visit Citta Vecchia, a quaint old city seven miles away. They were amused that their train travelled ‘at the enormous speed of seven miles an hour’ with a lot more turbulence than they had felt on their submarine. More humour was to follow as they needed to push their horse-drawn conveyance up the hill to their hotel. Marsland believed this was the introduction to ‘paying for something you don’t have, a usual occurrence in foreign parts’. Their Italian dinner did not suit their palate but they decided to engage a guide recommended by the hotel keeper, to explore further. The guide turned out to be around 80 and walked exceedingly slowly but the old bloke had a good command of English and the submariners were soon marvelling at paintings, mosaics and marble work, the likes of which they had never seen before. Deep in the catacombs and caves, cut into stone recesses, were the bones of the departed. The men were delighted ‘to get out of the place, for it had a creepy feeling attached to it’. Interestingly they decided not to spend an additional night in a hotel and returned to the submarine ‘for a good night’s rest’.10

On Monday 16 March they left Malta at 5.30pm for Port Said, the next 1,000 mile (1.609 kms) stage of their trip. AE2 was again in tow to allow for routine maintenance. Early on the Wednesday the tow rope parted. Two hours later with the tow rope mended they were off again but within another couple of hours much ‘to our sorrow’ the tow rope parted. Minor repairs on the engines were hastily completed and the crews were delighted when the boats continued under their own power at good speed. Three days out of Port Said AE1’s steering gear jammed hard starboard, a brass sleeve on AE1’s starboard engine drive shaft seized and the engine clutch could not be engaged. ‘If she had not been astern of station she would have hit the tow. Stopped for 4 hours’.11 On 18 March the tow rope parted more than once. On 19 March AE1 was again in tow when the rope parted. It had also been found that ‘Bearing oil coolers were started but found to be of little use, only reducing temperature by 2 degrees’.12 Both submarines arrived in Port Said Harbour with engines running at 6pm on Friday 20 March. The heat was already oppressive, ‘the engine room was unbearable and all the steelwork was burning hot to touch’.13 AE2 Commanding Officer Lieutenant Stoker recorded ‘A very unpleasant heat’ and later that one of his crew ‘had slight attack of heat apoplexy’.14 The decision was made to paint the hulls of the submarines white, making them look ‘like two big hydroplanes with the big white awning set’.15

The submariners felt even less comfortable ashore in this very different Middle Eastern culture.

The married women were mostly veiled and wore a small piece of bamboo extending from the forehead to the bridge of the nose.16

They were assailed by ‘awful noise …commotion’; the heat was stifling and the flies kept ‘our arms well exercised’. Most of all they were ‘constantly accosted by beggars’.17 The imposing monument to the engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French developer of the Suez Canal, bore witness to these strange vessels which also quickly became items of curiosity for the local population. Crews were pleased to return to their submarines and the next 90 miles proved a much more exciting adventure as they traversed the Suez Canal, truly an amazing feat of engineering.

In the Suez Canal ships were restricted to five or six knots but, owing to the greater difficulty in steering submarines at low speeds on low engine power, permission was given for them to proceed at 10 knots. It was as if they could reach out and touch the very sides even from their narrow hulled boats and they were delighted to accomplish the trip in eight and a half hours, whereas the average ship took around 10 hours.

The Arabs, who looked quite bewildered and shook their fists at us, the speed we were going was washing over the banks and some of them got wet.18

Whilst delighting in this part of their journey it was here that they ‘nearly had our first calamity’, when the Second Coxswain of AE1, Petty Officer Henry Hodge, fell overboard. Fortunately he cleared the propellers and was picked up about a quarter of a mile astern by a Canal Authority steamboat. The submarines left Suez at 10am on Tuesday for Aden, again with AE2 in tow. The crews knew that as they entered the tropics their comfort on this journey would surely be tested. Lieutenant Commander Besant realised that his crew was already struggling with the cramped conditions and lack of personal space, so he allowed a mess deck over the beam torpedo tubes which added ‘gracefully to the comfort of the men’.19 A salt water canvas bath could be rigged on the upper deck. Although AE1 had an ice chest and ice-making machine the crew were effectively camping with very limited meal variety. Occasionally freshly baked bread was sent over from Eclipse but fresh vegetables were rare and one sailor was removed suffering from anaemia. An unexpected and very welcome delicacy flew in from the ocean – flying fish which landed on the submarine saddle tanks and never managed to return to the deep.

During the next stage of their journey they travelled at the same speed as the German steamer Altmark. It was comforting that the ship remained abreast at a distance of around 150 yards (137 m), ‘it seems to brighten you up a bit to have something to look at’.20 Little did the submariners realise that within a year the sight of a German ship would cause a very different response. On this occasion the small Australian submarine and the German ship kept company for five days and the crews were sad to part ways after about 450 miles (724 km). Marsland wrote somewhat gloomily that thereafter ‘even the porpoises would not remain with us many minutes’.21 The submarines were moving along at around 12 knots and it had been decided that each submarine would alternate on the tow rope every 24 hours. There was little to do but to play cards or read. Occasionally those who could manage a tune on a concertina offered a somewhat more melodic change from the monotonous throb of engine and machinery. It was a relief to get onto the tow rope and a ‘rest from the terrible din of the engines’.22 It also offered an opportunity to clean the boat up.

Very rough weather off the Tyebayer Islands was concerning and speed had to be greatly reduced for fear of breaking the tow rope. Their lagging spirits were raised later that evening when they passed the large liner Marseilles recently departed from Sydney. The liner wished them good luck but was all too soon lost from sight. ‘She looked very nice at night being well illuminated and the passengers could easily be seen.’ More long slow miles with nothing of interest ‘same faces to look at on board and a few yards to stretch your legs when you are not closed down’. The only change of programme was Sunday morning prayers.23

Men were being tested to their very limit. There was no escape: their personalities, their characters, their professionalism, all were under the closest scrutiny by those with whom they shared this small space. They wore the same uniform but they came from diverse backgrounds. They quickly became familiar and needed to appreciate differences and forgive annoyances as they fully realised that each man in the submarine determined their shared destiny.

Chief Stoker Harry Stretch (8265) on a larger vessel would probably have put the fear of God into juniors with his booming voice. He was uncompromising RN through and through. Born in Porchester, England, on 7 November 1875, the son of Samuel and Elizabeth Stretch of Stubbington, Portsmouth, Hampshire, he spent minimal time in school before becoming a labourer. The RN offered bountiful opportunities and he signed on for 12 years on 13 November 1894. His early years as a Stoker were spent on the battleships HMS Resolution, Victory I and II. He received his China Medal for service during the Boxer Rebellion. Numerous postings followed including the training ship for boys at Portland, HMS Boscawen and HM Ships Resolution, Marathon and Duke of Wellington. Stretch never married – the RN was his life – so it was no surprise that he was one of the first 100 volunteers for the new submarine service, joining the submarine depot ship HMS Thames for initial training on 21 September 1903. In keeping with service conditions he returned to surface ships several times including the 18,600 ton battleship HMS Bellerophon. Advancement to Acting Chief Stoker came in June 1909 and he was confirmed Chief a year later. By 1912 when submarines and their crews were being prepared for the RAN he was ‘Controlling Chief Stoker’ at HMS Dolphin (Fort Blockhouse). The RAN was fortunate to have on loan a Chief of his experience and knowledge. This man of formidable appearance and manner quickly earned respect – his juniors were just pleased that given the confines of a submarine Stretch was unable to exercise the full capacity of his vocal cords when they erred.

A trio of Stokers would concur with this. Stokers 1st Class Henry Joseph Gough, Richard Baines Holt and James Guild may have questioned their luck in volunteering for a three-year loan to the RAN only to discover their Chief was Harry Stretch. It was a double-edged sword. Their boss was one of the most experienced and they would learn a great deal; he was also a severe taskmaster, expecting maximum effort and attention.

Stoker 1st Class Henry Gough (RN 204767; RAN 8292) was born on 8 June 1883 on Portsea Island – a small, flat, low lying island off the south coast of England, which contained a large proportion of the city of Portsmouth – suggesting he came from a family of seafarers. He worked in a store until he could enlist as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class at HMS St. Vincent shortly after his 16th birthday. Drafts to HM Ships Agincourt and Collingwood ensued and promotion to Ordinary Seaman on his 18th birthday. Gough served on Duke of Wellington before joining the armoured cruiser Aboukir. It was during that draft he decided to change branches to Stoker. It might be the career his tiny 5 feet 3½ inch (161 cm) frame was best suited for. His sea service increased with drafts to Foresight and Philomel. Gough was awarded the Africa General Service Medal with a clasp for ‘Somaliland 1908-10’ and in 1909 decided to volunteer for submarines. Australia seemed like another great adventure but it meant a lengthy period away from wife Dorothy Ada and their son and daughter.

It is unlikely the paths of Gough and Richard Baines Holt (RN 300667; RAN 8266) crossed until they both entered the small world of submarines. Holt was born in Battersea, London, on 14 November 1891. He worked as a labourer until enlisting as a Stoker 2nd Class on 20 May 1902 being drafted immediately to HMS Duke of Wellington. Sea drafts included the battleship Revenge on 14 November 1902 where he was rated Stoker 1st Class on 8 March 1903, and the cruiser Leander which was the torpedo boat destroyer depot ship for the Atlantic fleet. From extreme cold to extreme hot; Holt found himself sent to the torpedo boat destroyer depot ship HMS Hecla and the China Fleet on 1 May 1905. He remained at the China Station with a transfer to the protected cruiser HMS Bonaventure. Holt’s career was exactly as the RN recruiting office promoted to working class Englishmen: ‘join the navy and see the world’. On his return to England he studied torpedo and mining, and on 16 September 1908 the 5 feet 4½ inch (164cm) two-badge Stoker 1st Class, sporting a tattoo of a woman’s head and cross on his right forearm, volunteered for submarines. Clearly his desire to visit far off places had not been quelled and he volunteered for RAN submarine service from 17 November 1913.

Like Holt, Stoker 1st Class James Guild (RN 302880; RAN 8287) was unmarried. Guild was a Scotsman, from Tibbermore, near Perth, and was born on 17 September 1883. His mother died when he was very young but his father William, a signalman at the Perth General Station, raised his only child to the best of his ability and James initially followed his father into the Caledonian Railways – into the locomotive shops. But James yearned for a life at sea and enlisted on 9 January 1903 for 12 years. Sea drafts included Duke of Wellington, Firequeen I and Duncan, in 1903. A 1906 draft to the torpedo depot ship Sapphire II came with promotion to Stoker 1st Class in July 1906. This draft proved uncharacteristically long, lasting until 18 January 1909, and may have been motivation to train for a different naval lifestyle because he volunteered for submarines on 4 May 1909. Drafts to Bonaventure and Vulcan followed. Whilst serving with submarine E5 ‘James was seriously burned, and several of his fellow crew members died’.24 This did not discourage Guild and after recovering in hospital he volunteered for the adventure of travelling to Australia.

The journey to Australia had become long, lonely and taxing and the heat was terrific, with the thermometer in the engine room showing 120°F (49C) and the submarine superstructure too hot to touch. Even the awnings provided little respite and the crew began drinking as much lime juice and water as they could stomach. Onboard AE1 10 electric fans tried vainly to reduce the heat day and night. Maintenance work could only be undertaken in the early evening or very early in the morning and as they neared the equator Marsland wrote: ‘another scorcher’. He joked: ‘I am diminishing in size already’ and ‘soon there will be no crew left’.25

The diesel engines were consuming fuel at around four gallons (18 litres) per mile (1.6 km) but whilst this was not of undue concern the engine’s exhaust springs were – 15 had already been broken by the time they had tied up at Gibraltar. Water seeped into the hydroplane glands in the stern compartment (the after peak) and although engineering staff felt ‘the engines had behaved admirably’ all realised, as Chief ERA Marsland had predicted, that the propellers were very vulnerable to damage by any floating debris. 90 miles from Aden an even larger liner was sighted but the crew’s attention on the Maldavia was interrupted as the boat began to vibrate badly and they knew they had lost another propeller blade, delaying their greatly anticipated arrival into Aden.

Aden’s floating dock could only lift 750 tons but the submarine weighed over 800 tons. The only option was for the divers to attempt a propeller replacement at sea, a very hazardous exercise. Marsland referred to this rarely accomplished task as ‘a long and tedious job’, three days working night and day. As a diver he felt the brunt of responsibility.

Drawing bolts and heavy plates had to be made to force the propeller off and staging rigged up, and with good and hard work and perseverance the new propeller was securely fitted and key ways cut expertly, in two days under great difficulties. The hammer used weighing 56lbs (25.4kgs) and the spanner of the propeller nut over 1cwt (51k), and the propeller 7 cwt 10 lbs (36070kgs), not very easy things to juggle with [sic] underwater and in hot weather.26

The Artificers were clearly relieved and pleased with their professionalism to the point of being undeterred that this allowed them only two hours ashore, in a place referred to by Henry Kinder as ‘the last place on earth, just barren hills, there was nothing of interest to see’.27

It was 6 pm on April Fools’ Day when the submarines finally departed for Colombo and the longest part of the journey – some 2,000 miles (3,219kms). Monsoons were of real concern at this time of the year; they were capable of turning the sea into a raging tempest in a very short time in which the tiny submarines could be destroyed. Fate smiled and in calm seas they reached Colombo just before midnight on Thursday 9 April. In port was their next escort HMS Yarmouth which would accompany them to Singapore. An enormous amount of spare gear and crew personal belongings were transferred. Crew members were exchanged and with a little regret RN loan personnel noted the happy expressions on those returning ‘home’ to Britain.

Following the final transfer and settling-in process, the men were allowed to enjoy the delights of Colombo – and delights they were. After the barrenness of the Middle East they relished strolling through a canopy of lush jungle – ‘the scenery was grand, fruit growing by the roadside and coconuts abound everywhere’. Local Sinhalese tunes were not exactly music to the ears but the submariners were made to feel very welcome and spent one ‘jolly good afternoon singing and playing the piano’. Marsland made plans to revisit a new friend on ‘my return to England’ at the end of his loan three-year period to the RAN – a promise he fully intended to keep. As final departure preparations progressed they were besieged by the usual hawkers offering to remove corns from feet or offering jewellery for prices they were assured could not be beaten – until you asked the next sailor what he had paid – and tattooing ‘anyone who wishes to become a picture gallery’.28 It was always difficult to leave a port where you had been made to feel so welcome but on the evening of 14 April Yarmouth took AE1 in tow just outside the harbour. There was pleasure in the beautifully calm sea and a bright moonlit night and the anticipation of arriving in Singapore on 20 April after another long 1,505 miles (2,422kms) at sea. For seafarers there was always that sense of regret coupled with anticipation.

The advertisement which appeared in British newspapers had been as exciting as it was enticing.

Now so far away from ‘home’ and after such a gruelling trip with the end not yet in sight, some of the volunteers could be forgiven for doubting their decision to sign on the dotted line. Leading Stokers John William Meek, Sidney Charles Barton and William Elliott Guy had many demanding days to consider the wisdom of their decision.

John William Meek (RN 218676; RAN 8290) was born at Woolwich, Kent, on 12 November 1886 and on leaving school was employed as an errand boy. He joined the RN as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class at HMS Boscawen on 25 January 1902, was rated Boy Seaman 1st Class on 28 October 1902 before signing on for 12 years on his 18th birthday. Promoted to Ordinary Seaman, as lowly in the RN rank structure as that was, Meek would have been delighted with his significant pay rise and to be finally considered a ‘man’. He served at sea on HM Ships Minotaur and Agincourt and the battleship Bulwark in 1903. John Meek was then re-categorised to Stoker 2nd Class in December 1905 before being drafted to the Mediterranean fleet torpedo destroyer depot ship Vulcan. Rated Stoker 1st Class on 25 October 1906 he continued to serve onboard Vulcan. John Meek volunteered for submarines on 7 September 1909. By November he was back in Vulcan which was now ‘Submarine Depot Ship for Submarine Section VII – Home Fleet at the Nore’.30 This was followed by a draft to the submarine depot ship Mercury (Submarine Section IV) at Portsmouth in September 1909. By 1 November 1912 he was in the submarine depot ship Bonaventure and was promoted to Leading Stoker the same day in the following year, before answering the RAN recruiting advertisement. He was another designated ‘spare crew’ but personnel shortages would see him join AE1, and the future he and wife Maud Lillian had imagined changed dramatically.

Leading Stoker Sidney Barton (RN 309518; RAN 8288) was born at Twickenham in London on 20 April 1885, the son of George and Agnes Barton. He married Twickenham lass Emily Elizabeth and was employed as a labourer until enlisting in the RN as a Stoker 2nd Class at HMS Nelson on 18 January 1906 for the standard 12 years. In 1906 he was drafted to Victory II and Pembroke II with his first sea draft being the protected cruiser Endymion. On 1 May 1907 he was rated Stoker 1st Class and a year later served on the battleship Dominion before volunteering for submarines on 28 December 1908. Submarine training commenced in Portsmouth onboard the submarine depot ship HMS Thames. On 15 October 1912 he was drafted to the submarine depot ship HMS Bonaventure (5th and 6th Submarine Flotillas) moored at Harwich. Promotion to Acting Leading Stoker came on 1 November 1913 and within the month he was loaned to the RAN for three years, another designated ‘spare crew’.

William Elliott Guy (RN 290601; RAN 8291) felt he had less to return home to with the unexpected death of his young wife Ada Lydia. Born at Bedminster, Bristol, on 9 June 1880, Guy was a farm worker who went to sea from 19 November 1898. Service included HMA Ships Duke of Wellington II, the battleship Majestic, the cruiser Warrior and the battleships Russell and Queen. Guy was promoted to Stoker 1st Class on 1 July 1906. Like Holt he was drafted to the depot ship for torpedo boat destroyers in the Atlantic, HMS Hecla. On 12 September 1908 Stoker William Guy volunteered for submarines. Whilst on the submarine depot ship HMS Maidstone he was promoted to Leading Stoker on 28 January 1913 and subsequently applied to join the RAN submarine service. Guy was designated ‘spare crew’ although he found himself included in the AE2 commissioning crew photograph and would soon find himself on Australia’s first submarine.

Continuing the journey the only excitement over the next six days and distance of 1,505 miles (2,422kms) was the appearance of a whale which dwarfed the boats. It was impossible not to feel exhilarated by the distinct waterspouts and slight breaching of this majestic creature from the deep. On 18 April AE2 was taken into tow having run 826 miles (1,329kms) ‘comfortably’. A violent storm caused some excitement but fortunately quickly abated and by noon the submarines were passing Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. The journey had become painfully monotonous to the point that all ‘were getting sick of the quietness and dullness of the run, nothing to brighten you up at all’.31

Chief ERA John Marsland volunteered to arrange a concert. He posted a programme on the notice board; a platform and mess stools were organised. The concert commenced with a banjo, mandolin and violin march but ‘something went wrong with it, I think the heat had a lot to do with it’, Marsland decided. The quality of the music continued to be at best of very dubious quality particularly a rendition of ‘Kitty Dear’ by a sailor who struggled to find the right pitch and key and who alleged this was entirely due to the faces being pulled by his fellows. The consensus was that if this song was sung to his lady friend he would quickly need to find another.

Marsland took it on himself to offer the comic song ‘Ding Dong’ with banjo accompaniment, which failed to impress. Another sang ‘It nearly broke his poor old mother’s heart’ in such a sympathetic manner that after only one verse he was threatened with every manner of thrown object – tough men of submarines attempting to disguise their own homesickness. There was ‘a recitation by an Australian’, and the Captain sang a song accompanying himself on the banjo ‘which went down very well’. Regardless of protestations the concert had provided ‘a jolly good evening’ and the men retired more relaxed and cheerful, if not determined that their fellow submariners should desperately seek musical tuition.32

The following morning the course was altered to the south-east and tropical showers provided a pleasant if brief relief. The heat was unbearable and sleeping in hammocks out of the question. Sleeping above was also difficult due to the tropical downpours and strong winds which not only drenched bedding and clothes but all manner of material wrapped itself around the wireless aerial and flew away, taking the aerial with it. Another ship, Udometus, passed with the wonderful information that HMAS Sydney was already in Singapore. The men were counting down the days and miles. There was little to do to pass the time but it offered an opportunity for men from different countries who were now a crew to learn more of each other’s backgrounds – to share prized family photos as well as childhood and navy service dits (stories). Some within the AE1 crew were already familiar – like Stoker Petty Officers William Waddilove and John Moloney, both Australians, who had served together in the ANF. They formed a good relationship with Charles Wright (7395) who had enlisted in England upon seeing the newspaper advertisement. Previous RN service meant he was quickly accepted and promoted to Leading Stoker in December 1912. Just days before, on 16 April, Waddilove and Moloney had welcomed this 5 feet 9 inch blue-eyed 25-year-old Londoner to the substantiated rank of Stoker Petty Officer. The submarine was dry (alcohol-free) but they still managed to find a concoction, not entirely pleasant, for him to consume as part of his initiation. In return he would be required to shout them more pleasant alcoholic beverages at the next port.

Unknown to this diverse group of officers and men was that their progress and pending arrival was being reported in the Australian media with enthusiasm. The Sydney Morning Herald had kept its readers informed of the journey and how these mysterious vessels would arrive in Sydney Harbour on 15 May 1914. Gradually the date was pushed later and on 20 May this became ‘on Saturday next’. There had, according to the newspaper, been a ‘slight mishap which had been speedily rectified’. It referred to an ‘incident’ which occurred on 1 May whilst the submarines were proceeding through Lombok Strait, AE1 being towed by HMAS Sydney. The media report that the entire journey by Australia’s first submarines had been ‘an interesting one in many respects and was only attended by one mishap which however was speedily rectified’,33 was clearly untrue. The public was not to know that there had been many mishaps, many potentially dangerous situations and the incident in Lombok Strait and days earlier an incident off Singapore, were not ‘slight’. The veil of secrecy and lack of truth meant that Australians would never know or fully comprehend what their military volunteers were subjected to in the coming months and years. The mishaps off Singapore and in the Lombok Strait illustrated this clearly.

HMAS Sydney had arrived at Singapore on 15 April and needed to wait until 21 April before the Australian submarines finally arrived after a marathon run of 17,010 miles (27,375kms). For the Australians it was wonderful to finally feel part of their own navy, to mix with others in long conversations where explanation was unnecessary, to be comforted by the Australian drawl. Unfortunately Sydney could not offer shipboard accommodation and relief from their fetid, confined quarters. The submariners felt they were in the inferno of hell itself as they attempted general maintenance, making Singapore shore leave even more of a delight. They particularly enjoyed the abundance of fresh tropical fruit, the unusual assortment of animals, the eclectic population with their unusual cultures and, of course, the very tasty Singapore beer. Chief ERA Marsland and his fellows ended up at the British Army Engineers Mess where they enjoyed a hearty dinner, billiards and ‘as much to drink and smoke as we liked’. As Marsland enthusiastically wrote this was ‘quite a treat to us after being confined on a submarine for 5 days’.34 There was no urgency to return to their boats so they bunked down in any mess space. The consequences of such a wonderful levity were duly suffered and clearly visible the following morning.

Able Seaman George Hodgkin (RN 226508; RAN 8283) was the type of navy man one was very reluctant to challenge, regardless of his diminutive size of 5 feet 2½ inches (159cm). Hodgkin was born at Lenham, Maidstone, Kent, on 16 April 1887. He worked as a labourer until he could enlist as an RN Boy Seaman 2nd Class at HMS Impregnable on 27 April 1903. The following year he advanced to Boy Seaman 1st Class. An adolescent had to be of stern stuff to survive RN Boy Seaman training particularly as a junior sailor of small stature on cruisers and battleships such as HM Ships Sutlej, Irresistible, Majestic and Venerable. Along the way Hodgkin qualified as an Able Seaman Torpedoman, before commencing submarine training on 7 May 1908 on the submarine depot Ship Bonaventure (8th Submarine Flotilla) at Portsmouth. Hodgkin did not shirk from having to re-qualify as a Seaman Torpedoman in October 1913 so he could volunteer for the RAN, another to be loaned for three years as ‘submarine spare crew’. Not only had Hodgkin gained respect from pursuing a career in the RN with no quarter expected or received but he was also a former fleet boxing champion. His ability in the boxing ring against larger opponents had surely enhanced his survival in the navy but off Singapore in April 1914 the two-badge Able Seaman also took it upon himself to use his right cross in an emergency.

The AE1 diving apparatus had been found wanting as early as sea trials. The trimming experiment on AE1 showed that all internal main ballast except ‘Y’ could be filled. A second test was recommended as soon as possible but time constraints had delayed this. It was hoped the re-test would be conducted on arrival in Sydney. For whatever reason, AE1was submerged when the submarine became stuck in the mud in Singapore Harbour. It was disconcerting as attempts to dislodge the boat from its trap proved to no avail. The minutes ticked by as various manoeuvres were attempted. Some began to subconsciously count and calculate how long it would take for the fresh air in the submarine to dissipate and a few glances went to the two caged white mice who would begin to squeak should the air become foul. It was not exactly a state-of-the-art alarm system but it was a trusted one. More time passed and the perspiration on brows had as much to do with concern as internal temperature. ERA Jack Messenger’s thoughts returned to his Victorian home in Ballarat, his mother Isabella35 and how many years it had been since he had seen her. A crewman ‘panicked as the predicament worsened’. The former Fleet Boxing Champion, Able Seaman George Hodgkin, stepped forward and without hesitation ‘knocked him out to quell further problems’.36 It may not have been one of the most perfectly executed punches Hodgkin had delivered but it was one of his most effective. AE1 began to pull free from the mud and slowly rise to the surface.

Oiling the submarines anchored out from the shore also proved treacherous and Petty Officer Henry Kinder of AE2 watched as the seas became rougher and the barge he was on ‘with about forty coolies broke away and drifted a couple of miles out’. On this occasion the rescue came reasonably briskly, in the form of HMAS Sydney’s steamboat.37 The submarine Captains were unimpressed that three new propellers had not reached Singapore, even though they were now days behind the Admiralty programme and there had been ample time. There continued to be problems with the engine cylinders. AE2 found ‘4 rings smashed in small pieces’.38 There was also concern that correct oil supplies had not been arranged; ‘no lubricating or fuel oil of the required quality could be obtained at Singapore for the submarines’.39 Besant believed this was a bad oversight because he had been promised this would be done before he left England. ‘The oil suitable for Submarines has a density of .893 with a flash point of 208 Fahrenheit’.40 Some could be obained from Hong Kong but this would take a month. It was decided that the oil supplied to Sydney would have to suffice, as unsatisfactory as this was.

Interesting port Singapore, but it was nonetheless a relief to watch Singapore vanish in the distance on the morning of 25 April; two exciting incidents had been enough and Australia was getting closer by the day. Desperate for cooler weather the submariners were thoroughly pleased to cross the equator at 6.55pm. Finally they were ‘started on the winter side of the world, much to our delight, for we were getting rid of our worst trouble (heat)’.41 But even this part of the trip came with unpleasantness. Sydney had been coaled with poor quality coal in Singapore and the cruiser Commanding Officer, Captain John Collings Taswell Glossop, RAN (later Vice Admiral, CB), was unimpressed that ‘the coal was of a most inferior description and … I relied on the superior quality of Welsh coal’.42 The sparks and cinders pouring out of the cruiser’s funnels blew back onto the submarines, adding to crew discomfort and causing navigational problems. According to Stoker it was ‘a frightful nuisance’.43 Those on the upper deck needed to wear goggles but even below decks for the AEI Coxswain, Petty Officer Thomas Guilbert, this was particularly onerous and his responsibilities for driving this boat and crew weighed as heavily as they did on his captain Lieutenant Commander Besant.

The first day of May began peacefully calm as the submarines and their escort travelled through the Lombok Strait. Reefs abound on both sides of the shipping channel but submariners slumbered content in the knowledge that the Australian cruiser would clear any obstacle as they trailed behind. At 1.30am they were abruptly woken. The tow rope between AE1 and Sydney had parted and fouled around the cruiser’s rudder. Chief ERA Marsland tried to understate the situation in his monologue: ‘Engine room staff were quickly roused … hatches closed, and engines got ready’. The night was very dark and the sea ‘infested with sharks’. The Chief ERA was a seasoned diver and navy man but wrote that even he believed they were placed in a ‘very precarious situation’. AE1 was not yet under full power and began drifting towards rocks with a jammed helm, across the path of AE2. Stoker ordered a rapid course change to starboard but his submarine was caught in the current and stuck on its original course.

It looked as if a collision was absolutely inevitable, as there could be no hope of the engines answering to the order of ‘Full Speed Astern’ before the boats struck. As a last resort, we in AE2 put the helm hard over the other way; a lucky swirl caught the boat’s nose at the same moment, helping to swing her off to starboard – and we whizzed past AE1’s stern at a distance of some three feet.44

Stoker wrote in his boat’s log ‘both these events could hardly have been closer to calamities’.45 That had been enough excitement for any day. For Sydney the drama continued. Shark-infested waters and darkness meant the Australian cruiser could only take anchor offshore until morning. Only then could divers be sent below to untangle the tow rope from the rudder whilst look-outs shot ‘three large sharks’.46 The submarines continued on alone, simply anxious that this journey finish; HMAS Sydney caught up within hours and took AE2 into tow. The day of 3 May was uncomfortable as the Arafura Sea churned, waves washed over submarine bridges and hatches were closed down. Marsland wrote ‘we shall be very glad when Port Darwin is sighted’.47

At 6am on 5 May Charles Point and Australia appeared at last. The excitement of the Australians was infectious though their stories had become more embellished the closer they approached the Australian coastline. According to them this country was the most beautiful and so full of friendly people and vibrant cities. Members of the RN, unfamiliar with the predilection of Australians to exaggerate, could be forgiven for wondering when they first landed in the small Northern Territory town of Palmerston, comprising three hotels and a number of corrugated and wooden houses and a cluster of shops in Chinatown. Nonetheless the welcome was genuine, highlighted by an archway emblazoned with the words ‘Australia Welcomes Her Defenders’. It was glorious to land on Australian soil ‘the land we have been so anxious to see’48 and all enjoyed a day local residents had clearly put some thought into. A sports carnival had been arranged as had a concert, and visiting officers and sailors clearly realised the population of about 300 ‘white people’ had collectively defrayed the cost so as to ensure ‘things as bright and cheerful as they could for us’. It was a ‘splendid afternoon’ particularly when the sports commenced with a pillow fight across a bar which caused much laughter. For the British this was also their introduction to the Aboriginal community. Though the language of the day would in another era cause offence Chief ERA John Marsland’s account showed his view that these indigenous people were friendly and fascinating.

There were also races for the blacks who are very good runners … After the concert the blacks gave a show, which included a dance called Corobberoe [sic] a very strange dance. Men and women sit on the grass, the men blow through a large bamboo stem, whilst the women clap their hands and make a weird noise, and the Nigger rushes out and does his part of the dance, which is always the same.49

The corroboree became even more interesting when some of the submariners joined in.

Their journey continued to Thursday Island where mail was collected and AE1 placed on tow. Letters from home, much delayed by distance and time, were incredibly welcome and the crews delighted in immersing themselves in news of family and friends. The sea grew increasingly choppy requiring the after hatch to be closed for too long. A quick abatement in the weather allowed men to wash uniforms and hammocks and hang them over railings. Again the weather deteriorated so rapidly that the men could only watch as their belongings disappeared over the side, again taking the wireless aerial with them. Australian Petty Officer Henry Kinder decided the signalman lacked a sense of humour when he ‘said some nasty things about people washing hammocks’. It was however the fourth time this had happened so Kinder conceded he might be forgiven.50

AE1 suffered ‘some mishap’.

The dumb bell bolts for shaft clutches kept carrying away, owing to shaft wanting re-alignment.51

The submarines entered the Great Barrier Reef and began making good speed, past an impressive coastline. They arrived in Cairns Harbour at 9.30pm on 12 May and anchored overnight before proceeding the following morning. Again those new to this land were surprised by the size of the municipality – where were these bustling modern cities the Australian crew members had been promising. But again what was lacking in size was more than made up for by welcome. Cairns citizens arranged a trip to Barron Falls for the submariners and ‘the sheer fall of 700 feet is a most wonderful sight’ wrote Chief ERA John Marsland. Tropical orchids too captured the imagination. It was an easy consensus: We had a good time at Cairns’.52

Australia’s first submarines continued down the Queensland coast and like so many before them and so many after them these visitors from Britain marvelled at the strong light and vibrant colour, ‘passing some beautiful islands and scenery’, on schedule to reach Sydney by noon Saturday 23 May. But Mother Nature was not quite finished with these men and their boats – another violent storm broke over submarine hulls, a storm as violent as ‘very few’ of the seasoned navy officers and men

had ever experienced and ever want to again. The seas were so violent that for hours very little could be seen of either submarine, then to make matters worse the wind sprang up and then a hailstorm of great velocity came along, obscuring the ship and islands from view, and we were being tossed about most unmercifully.53

Even tied-down gear broke free and the submarines were soon full of loose objects which moved around dangerously. They could not believe their luck – so far and yet still not far enough, so arduous a voyage and it was not yet over. ‘To our disgust’ and ‘misfortune …we were being tossed about most unmercifully and is not the slightest sign of any abatement in the weather … We struggled on’.54

Besant decided as the seas became even worse that there was no alternative but to make for Moreton Bay and anchor in safe harbour. He needed to safeguard boats and crews though realising how disappointed and anxious crews were ‘to get our journey over’.55 Those waiting in Sydney, and his superiors, would undoubtedly have mixed feelings about the programme change but safety took priority; putting the programme back 15 hours was ‘most unfortunate and aggravating but absolutely necessary’.56 AE1 was in trouble again, breaking another cast steel toggle belt. Repairs took four hours. The following morning they continued to steam down the Australian coastline and frustratingly again were soon in the teeth of another gale, one even more violent than the previous one. The submarines struggled on through angry swells. AE2 lost its port foremost hydroplane guard. Not until 23 May did the weather finally moderate. They were still 100 miles (161km) away from Sydney. Realising it was impossible to arrive at noon as authorities and the Australian public would have preferred, speed was reduced to allow submarines and crews a slight reprieve from what had proved a taxing final leg of a harrowing journey so they could arrive in a better condition the following morning. It would take some time before these officers and men could fully appreciate the scale of their accomplishment – what Chief ERA John Marsland referred to as ‘a most wonderful journey of endurance both men and engines’.57 It had taken 83 long days, 60 at sea, to arrive in this harbour that Australians had been boasting was the most beautiful in the world – they just needed to wait until morning to see if this was true.

FOOTNOTES

1 Roskill, S.W. Naval Policy Between the Wars, Walker, 1968, p. 231.

2 The information on RN service of those onboard was provided by Barrie Downer.

3 AWM50 18/1 Part 7, ‘Submarine AE1 Nominal List – Lists of effects of deceased’, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

4 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

5 Kinder, Diary.

6 Marsland, J. 13,000 Miles in a Submarine in 83 days, Sea Power Centre, Canberra.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

12 Ibid.

13 Kinder, Diary.

14 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Kinder, Diary.

23 Marsland, Journal.

24 Brenchley, Fred and Elizabeth. Stoker’s Submarine (ANZAC Centenary Edition), ATOM, 2014, p. 232.

25 Marsland, Journal.

26 Ibid.

27 Kinder, Diary.

28 Marsland, Journal.

29 Liverpool Echo, 24 January 1913, courtesy, Barrie Downer.

30 Downer, Barrie. ‘Submarine Crew List’, 4 November 2011.

31 Marsland, Journal.

32 Ibid.

33 The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 May 1914.

34 Marsland, Journal.

35 Ryan, Vera. email 11 March 2011.

36 Hodgson, Keith. Email 10 March 2011. Keith Hodgson’s father was Leading Signalman Aubrey Hodgson (7066), former ANF, later Yeoman, later Chief Petty Officer, who was sent to England as a member of the commissioning crew of HMAS Melbourne. He purchased his release in October 1913 but re-enlisted on 19 August 1914 and served during WWI. He is believed to have told the story of a fellow communicator who was put on AE1 from HMAS Sydney in Singapore in an attempt to make the wireless operative. It was whilst they were testing this at sea that the incident is supposed to have happened. There are doubts on the accuracy of Hodgson’s diary but this story was repeated by Submariner Able Seaman Reuben Joseph Edwin Mitchell DSM (7476) to fellow Ballarat residents and friends, the Messenger family, whom he visited on leave after the war. His diary was given to the Ballarat Library. Ballarat Library has been unable to locate the diary.

37 Kinder, Diary.

38 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

41 Marsland, Journal.

42 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

43 Ibid.

44 Brenchley, Fred & Elizabeth. Stoker’s Submarine, Harper Collins, 2001, p. 18.

45 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

46 Marsland, Journal.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Kinder, Diary.

51 MP472/1 16/14/4771, ‘HMA AE1 and AE2 – voyage to Australia (including log book)’, National Archives, Melbourne.

52 Marsland, Journal.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 May 1914.

56 Ibid.

57 Marsland, Journal.