THE MOST intriguing oral history associated with a home is, perhaps, “This house came on the train.” A train pulls into the station and leaves two boxcars on a landing. Inside are all the materials needed to construct an entire house. The framing boards are cut to size at the mill to facilitate rapid and accurate construction. The purchaser has chosen the model, selected door and window styles, specified the desired types of wood, decided on the exterior cladding, and even selected the paint colors. These well-designed, practical homes were made of top-quality materials. This is a mail-order kit home.

These homes were marketed on a large scale by mail-order catalog from 1906–83. Eight major U. S. companies and a host of small companies with only local distribution sold such homes primarily in the United States but also in Canada. Aladdin Company once shipped an entire village of homes to Birmingham, England, to provide housing for workers at the Austin Motor car factory.

The catalogs were updated, usually annually, to allow for the addition of newer styles of homes and the deletion of unpopular models, and to accommodate price changes. Companies also placed advertisements in national magazines and newspapers in major cities as a way to promote their homes.

Over time, various terms were used to describe these homes. In a circa 1907 catalog, Aladdin Company advertised “the original Knocked-Down Houses, with every piece cut to right length, breadth and thickness and planed on all four sides.” Sears, Roebuck used the terms “cut and fitted,” while Gordon-Van Tine featured the “ready-cut system,” and Pacific Homes dubbed their models “Ready-Cut” houses. Harris Brothers described their kit homes as “Cut-to-Fit.” Lewis and Sterling used no such descriptive terms, but referred to their product as “Lewis-Built Homes” or homes “Built by the Sterling System.”

The homes were copies of the U. S. house styles most popular during the period 1900–80. Despite widespread sales of thousands of mail-order homes, they are rare when compared to the total number of homes built. Aladdin sales of 2,800 homes in 1918 comprised 2.3 percent of the 118,000 U. S. housing starts that year.

The popular 1930 Montgomery Ward “Cranford” model is, architecturally speaking, a Dutch Colonial Revival design with a Tudoresque gable added on the front.

Precut housing thrived until after World War II, when government regulation of the U. S. housing industry, tract housing construction methods, and increased popularity of prefabricated and mobile housing meant that precut housing companies could no longer compete financially.

The mail-order house company provided blueprints and construction materials. Lumber was provided either in bulk or as precut framing boards. The latter were known as “kit” homes. One source provided the buyer with all the materials required to build a house: lumber, roofing, doors and windows, flooring, trim boards, hardware, nails, clapboard or cedar shingles for the exterior siding, and enough paint and varnish to put two coats on everything. Of course, an instruction book was included to ensure that the structure was built properly.

This well-maintained “Cranford” is located in Charleston, West Virginia. (Photograph by Rosemary Thornton)

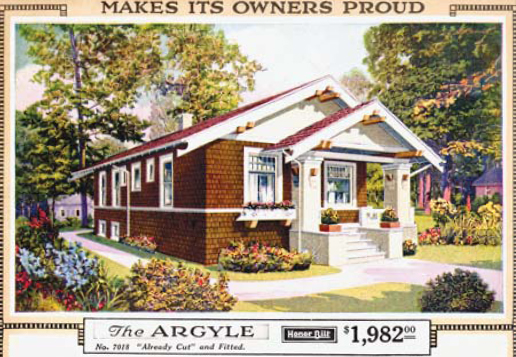

This “Argyle” built in Lexington, Kentucky, has been authenticated by a Sears, Roebuck mortgage record. (Photograph by Dale Wolicki)

As in homes built by standard methods, framing boards were customarily hard southern yellow pine. Flooring in living and dining rooms was typically oak, with maple and/or fir in the other rooms. Trim boards usually matched the flooring. Masonry such as brick and stucco could be chosen as an exterior finish for any design, but this was obtained locally, and the price was adjusted accordingly.

One-story homes with two or three bedrooms predominated mail-order home catalogs. The Sears, Roebuck “Argyle” model with its Arts and Crafts porch columns was built in many locations such as Bridgeport, Connecticut; Rantoul, Illinois; Kokomo, Indiana; Thornton, Iowa; Somerset, Kentucky; Bladensburg, Maryland; and Detroit, Michigan.

Lewis, another Bay City, Michigan, company, offered this “Rowland” model in the 1950s.

Materials were shipped primarily by rail, but also by boat, depending on the locations of the supplier and purchaser. Most customers ordered from the closest supplier, as the buyer usually paid the freight charges.

Researchers are lucky when a mailorder home identified in 2000 still looks exactly like its 1923 catalog image. Gordon-Van Tine’s model #562, an American Foursquare design, was popular in the early 1920s.

This Mid-Century Modern Ranch design from the 1954 Aladdin Company catalog is shown with the optional “scenic window.” Acknowledging that ranch-style designs evolved from architecture of the southwestern United States, Aladdin named this model “El Rancho.”

The mail-order company’s responsibility ended with the arrival of the sealed boxcars at the railway depot. The purchaser had several days to unload the material. In the early years, materials most commonly were hauled to the building site using a horse and wagon; later, motor vehicles were used. The majority of building sites appear to have been close to a railroad, but one purchaser is known to have hauled the materials for his house by horse and wagon from the Gordon-Van Tine plant on the Mississippi River in Davenport, Iowa, sixty miles east across the plains to his farm in Illinois.

Shown here as built in Colonial Heights, Virginia, This Gordon-Van Tine model #562 looks original except for the replacement iron porch rail and columns. Compare this picture with the one opposite. (Photograph by Rosemary Thornton)

Prices shown in catalogs typically included only the building materials; the cost of the finished house, including the materials, lot, foundation, and construction labor was usually at least double the catalog price. Prices for Sears materials ranged from $146.25 in 1911 for a two-room cottage to $9,990 in 1920 for a ten-room, two-and-a-half-story design.

Many upgrades and extras such as heating, lighting, and plumbing fixtures; storm windows; etched glass doors; stained glass windows; cherry or birch woodwork; and built-in cabinetry could be ordered at additional cost. Aladdin Company, in its 1978–79 catalog, listed the following optional materials: scenic windows, insulating glass, kitchen cabinets, insulation, folding closet doors, aluminum storms and screens, and patio doors. In fact, sales records show that Aladdin Company earned more money on upgrades and extras than they earned selling the basic homes.

Manufacturers claimed that the precut system would save the builder up to 30 percent in labor and materials compared to the cost of standard building methods. Few data are available to substantiate the exact amount of savings, however. In any case, the cost of a mail-order home was significantly less than the cost of obtaining a home by the standard method of hiring an architect, purchasing materials from various sources, and paying a carpenter to measure and cut every board. Companies were able to pass their savings on bulk material purchases along to the homebuyers.

In terms of construction time, a buyer of a mail-order home could expect to be living in the house much sooner than a neighbor who built traditionally. Sears, Roebuck claimed that the “Rodessa” model could be built in 352 hours using precut materials, compared to 583.5 hours using standard methods.

Homeowners delight in telling the stories of their mail-order homes. In 1913, George E. Allen decided to put up a Sears, Roebuck home on the farm he bought in 1900 in Raymore, Missouri. He chose model #227, a two-story “box house,” or American Foursquare design. Allen described the process of building the house in letters to his wife:

April: Dug the post holes

July: Have the cellar done

August: All sided up, window frames in and painted

September: All the carpenter work done

In 2000, the farm, still in the Allen family, was designated as a Missouri Century Farm. The family still retains the original contract for purchase of the home.

Susan Stamberg, a Chevy Chase, Maryland resident, initially was dismayed to discover she was living in a home from Sears, Roebuck. “Sears? In New York, you went to Bergdorf’s, B. Altman, Saks. You didn’t go to Sears,” Stamberg told the Washington Post in a 2002 article by Lisa Rauschert. Since then, she has bragged about her “Maywood” model, praising its design.

In September 2009, the Mickey family threw a birthday party for their one hundred-year-old Sears Roebuck model #118 in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. Model #118, later named the “Clyde,” is a two-story Victorianesque hipped roof house with gabled extensions. It was one of the very first models offered in the Modern Homes catalog, appearing from 1908–19. The Poplar Bluff home was built in 1909 by Walter R. Mathis for his son Thomas and wife Bertha. Their daughter, Ruth, was born in the finished house in December of that year. The Mickeys purchased the home in 1963.

The “Maywood,” such as this example in Glenshaw, Pennsylvania, was offered by Sears, Roebuck from 1927–39. (Photograph by Dale Wolicki)

It sounds like such a good idea for consumers to be able to obtain excellent housing at low cost that one could easily imagine universal popularity for the idea. However, the construction industry was among those who were not fans of mail-order homes. Architects, carpenters, lumber companies, millwork plants, roofing concerns, and hardware suppliers lost business every time someone purchased a mail-order home. Trade unions, contractors, and architects took out full-page advertisements in national and local publications, insinuating that mail-order homes were inferior and that the purchasers were fools. In April 1928, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters Local 363 took out an advertisement in the Elgin, Illinois, Courier News asking citizens to demand that union carpenters build their homes. However, these advertisements were few in number compared to those placed by mail-order companies advertising their wares.

For most U. S. homes, little information is available that indicates the architect or the contractor. Some communities ask for this information on building permits, but most do not. Information can be sought in contemporary newspaper accounts of new construction, in historical society archives, on fragile old blueprints, and in memories of elderly citizens, but the search is often frustrating, time consuming, and fruitless.

A word of caution to would-be seekers of mail-order homes: attempting simply to match a house with a catalog picture is insufficient, since most mailorder models are not unique designs but were closely copied from other companies or architects. Interior evidence and legal records, however, can determine with certainty whether a given house is actually of mail-order origin.

In a precut building, the easiest proof to find is a part number. Framing boards were numbered to facilitate construction. After construction, some of these numbers usually are still visible on ceiling joists, rafters, wall studs, and stair risers and treads. They are not found on trim boards, windows, doors, banisters, built-in cabinets, or mantels. Numbers are seldom visible on every board, and a bright flashlight is usually necessary to see them.

Sears, Harris, and, after circa 1930, Aladdin, used ink. Sears stamped solid numbers and letters near the ends of the boards, usually a capital letter followed by one or more numerals. Harris stenciled the markings in the middle of the boards, usually two-digit numerals or a letter and one or two numerals. Gordon-Van Tine, Pacific Homes, Montgomery Ward, Aladdin, Lewis, and Sterling wrote the numbers by hand in grease pencil, usually in the middle of the boards.

A post-1930 Aladdin part number. (Photograph by Cindy Catanzaro)

A Harris Brothers part number.

It can be difficult to discriminate between part numbers and random scribbling by carpenters. Part numbers are repeated on more than one board; multiple ceiling joists, for example, are likely to bear the same number. Boards serving different functions bear different numbers, but of a similar format. Carpenter’s marks are made in the same blue grease pencil as the handwritten part numbers and include such things as arrows, random lines, messages, and arithmetic. In the case of a precut home, it is not necessary to calculate the size of boards, so computations are good evidence that the building is not a precut kit.

Additional proof may include one or more of the following:

• blueprints with a mail-order model name, number, or company logo

• documents including correspondence, guarantees, instruction manuals, or parts lists

• title search and/or tax records listing a mail-order company as architect, buyer, seller, owner, or payer of real estate taxes

• mortgage records, in the case of companies that offered financing

• records of repossession or resale by the mail-order house company during and after the Great Depression

Sears part numbers were stamped on the sides and ends of boards.

Shipping labels, typically applied to an outside board in a bundle of lumber, also can provide evidence, but not proof, of mail-order origin. If the label is found in a house that is identical to a catalog model, it is strong evidence. Otherwise, it is weak, since mail-order companies also sold lumber and millwork regardless of whether buyers also ordered an entire house. The shipping labels are identical in either case.

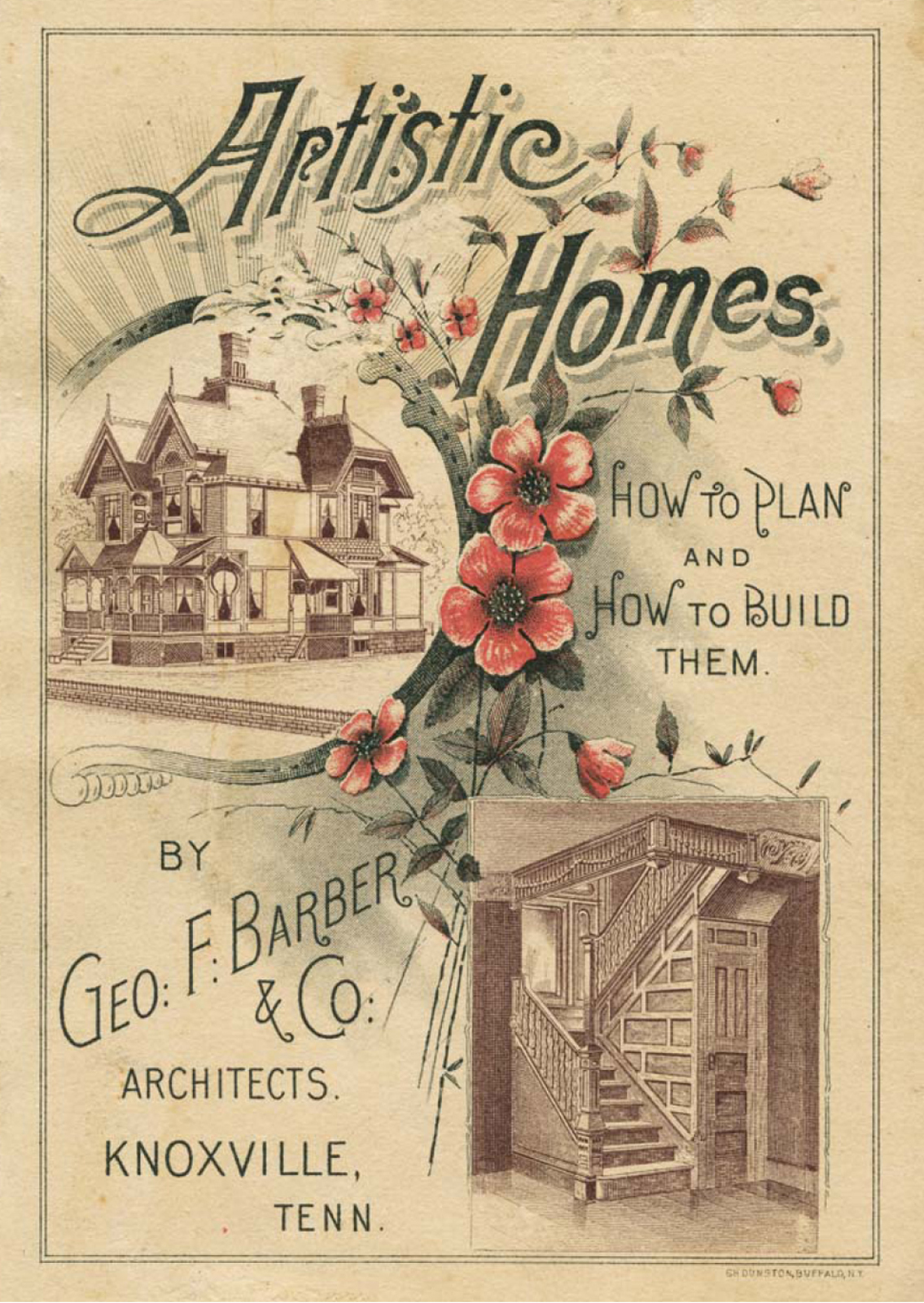

In 1894, architect George F. Barber of Knoxville, Tennessee, published his book of plans entitled Artistic Homes, showing his latest designs and their floor plans. Prices for the plans ranged from $10 to $50 depending on size and complexity.