MAIL-ORDER BUILDINGS covered the gamut of architectural styles popular from 1906–83, ranging from two-room vacation cottages to ten-room, two-and-a-half story homes, from chicken coops to sixty-by-ninety-foot barns.

Since the goal of mail-order home purveyors was to sell the maximum number of each design offered, styles tended to follow the popular trends in architecture. Therefore, mail-order homes rarely possess unique or unusual architectural features; instead, they blend in with the most common designs of each decade. This causes confusion a century later as researchers puzzle out how to identify mail-order homes.

The earliest catalogs were dominated by two-story vernacular designs, plus a handful of Victorianesque homes designed to accommodate large families. This is evident in examining Gordon-Van Tine’s 1909 catalog offering twenty-two two-story but only eight one-story homes. By 1915–19, Arts and Crafts and American Foursquare styles dominated the catalogs.

After World War I, several factors affected home sizes, among them high inflation, a shortage of materials, and population shifts. Many people were moving to small city building lots, and home size decreased. This became the era of the two-bedroom, one-story bungalow or cottage.

Revival styles proliferated from the late 1920s into the late 1930s: Colonial, Dutch Colonial, Tudor, Spanish, and Mission designs were the latest fad in real estate.

Designs offered by Pacific Homes of Los Angeles differed from those offered in the midwestern and eastern states. Since their market was primarily on the west coast, Pacific Homes models reflect the prevailing California Bungalow style, with low-pitched roofs, many windows, and large porches.

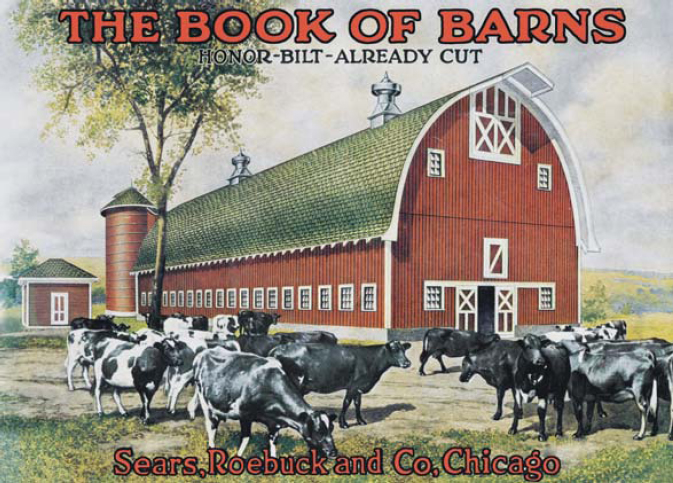

Prior to 1920, the largest segment of the United States population was rural. In consideration of the large farming population, major mail-order home producers—Aladdin, Gordon-Van Tine, Harris Brothers, Sears, and Wards—also offered barns and other farm buildings. Most prevalent were designs for gambrel-roofed barns, followed by gabled, gothic, round, and polygonal barns. Also included were hog and chicken houses, implement houses, granaries, and milk houses.

Montgomery Ward’s “Farmland” was targeted to rural areas where large families predominated. The nine-room home featured polygonal bays and pedimented gables.

Harris Brothers’ model #5010 is a large Arts and Crafts bungalow with a corner tower. This Louisville, Illinois, example is one of only two discovered so far.

Harris Brothers model #1025, such as this example in Elmhurst, Illinois, enjoyed popularity throughout the eastern and midwestern states.

The Sears “Martha Washington,” seen here in Lombard, Illinois, is a Dutch Colonial Revival style.

This unusual round barn, model #215, was pictured in the Gordon-Van Tine 1918 farm catalog as a testimonial from a satisfied customer in Manhattan, Illinois. The barn was still standing as of 2011.

In 1909, Gordon-Van Tine offered twelve agricultural buildings; as the demand grew, from 1918–36, so many were offered that separate Farm Buildings catalogs were published.

Aladdin and Pacific Homes played a comparatively minor role in the production of farm buildings, with only a small number of offerings between 1910–19. Montgomery Ward also offered a few agricultural buildings in their house catalogs from 1910–19. Harris Brothers offered only a few farm buildings in their house catalogs from 1912–18.

Sears, Roebuck 1919 Book of Barns has been issued as a reprint.

Sears, Roebuck joined this market in 1911 and became the major competitor of Gordon-Van Tine, offering specialty farm catalogs from 1918–29. As the agricultural population declined after 1920, so did the number of farm buildings offered. The total number of Sears barn models reached a high of twenty-six in 1919, but declined to thirteen in 1929.

Precut house designs were standardized to reduce waste in materials and to facilitate milling of the lumber. For example, the same lengths of joists, wall studs, and rafters would be used in many different models. Window and door size variations were limited, and the same basement stairway appears over and over again. Aside from the convenience of precut framing boards, kit homes were constructed exactly like a similar carpenter-built home.

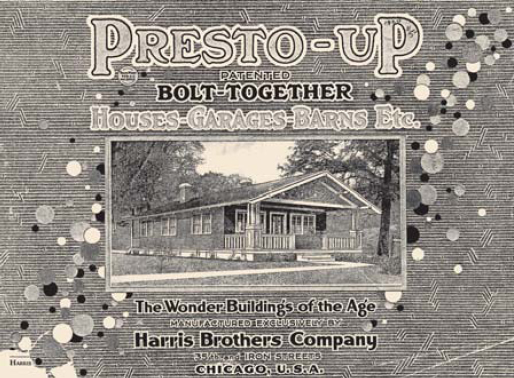

A kit home variant was the sectional home. Four-foot wide sections, be they wall, door, or window, were completely constructed at the mill and included framing and interior and exterior sheathing. The sections could be bolted together quickly at the building site, providing the buyer a home with little effort. The majority of these were small cottages, advertised to potential buyers as vacation homes, but commercial buildings also were available.

Sears, Roebuck dubbed their ready-made buildings “Simplex Sectional” and suggested they could be erected for summer use, then dismantled and stored under canvas until the following year’s vacation. In 1916, in addition to cottages, Sears offered sectional garages, a real estate office, a church, schoolhouses, a refreshment stand, election booths, a boathouse, a cobbler shop, a barn, outhouses, and even a photographic studio.

Gordon-Van Tine sold “Portable Houses” from 1910–16 and claimed to have been the “original purveyors of prefabricated houses.” However, at least one Cincinnati company offered portable buildings even earlier than that, from 1850–75.

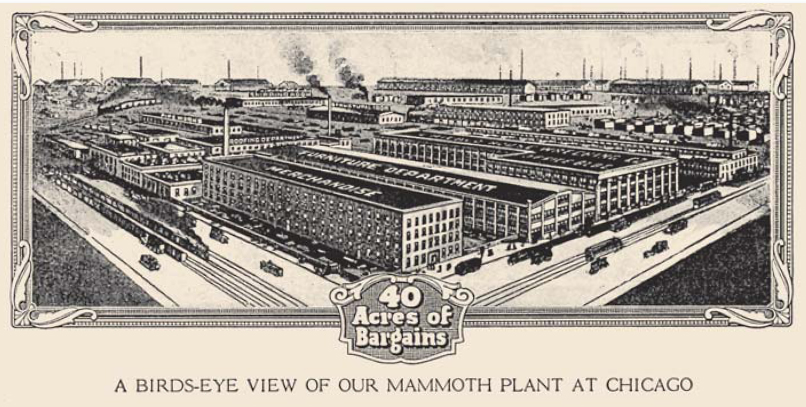

Harris Brothers operated this forty-acre plant at 35th and Iron Streets in Chicago.

In 1920, Harris Brothers published a specialty catalog featuring their sectional buildings.

Pacific Homes started business as Pacific Portable Homes, offering only sectional structures. Harris Brothers introduced sectional cottages in 1912 under the trade name “Perfection Portable Houses” and later changed the name to “Presto-Up.” Montgomery Ward sold a few Ready-Made houses from 1912–16.

After World War II, sectional construction was used for the majority of U. S. homes, which became known as “prefabricated” homes.

Given that mail-order homes were copied from the most popular architectural styles, it is not surprising to learn that mail-order companies also copied each others’ designs. This resulted in “look-alikes,” “clones,” or “twins.” Of course, because of legal strictures, they could not be exact copies. However, the differences often are trivial and therefore not easy to spot. For example, the Sears “Mitchell” model cannot be visually differentiated from the Aladdin “University” or the Bennett Company “Brentwood.” Only part markings and dimensions can reveal for sure which company built it. The Gordon-Van Tine “Kent” and identical Montgomery Ward “Newport” models are the same basic style as the “Mitchell,” but have slightly flared rooflines.

Mail-order companies also copied designs from plan books. For example, of the twenty-five homes offered in the 1909 Montgomery Ward catalog, fifteen are close copies of plans published by William Radford in 1908. Harris Brothers’ 1908 catalog contained twenty-six plans, twenty of which appear to be based on designs by Minneapolis architect Max Le Roy Keith. Perhaps the mail-order home companies actually purchased plans from these architects, or perhaps they hired their own architects to make minimal changes in others’ designs.

For the most part, the architects of mail-order homes remained anonymous. On blueprints, only initials identified the architects. The companies, not individual architects, held the copyrights of the designs. In 1925, Sears hired D. S. Betcone, the only architect of mail-order homes known by name, from competitor Aladdin, where he had worked for eleven years.

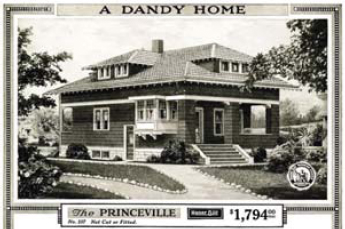

A common question is “What were the most popular models?” In the absence of sales records, the answer must be a speculation. Popularity varied according to year and geographic location. Sears even published two catalogs for 1920 containing different models: a Chicago and a Philadelphia version. If we assume that the most popular models were sold over the longest period of time, we can come up with some answers: small, architecturally conservative, and inexpensive homes appeared most frequently.

Regardless of which model they purchased, customers were encouraged to personalize their mail-order homes by adding porches, fireplaces, sunrooms, window boxes, trellises, or built-in cabinetry, and by selecting exterior finishes and colors. Of course, over the years, new siding has been put on, additions have been made, roofs have been raised, porches have been enclosed, and dormers have been added. This increases the challenge of finding mail-order homes today, since many no longer look like the catalog pictures.

The Wards “Newport,” Aladdin “University,” Gordon-Van Tine “Kent,” and Bennett “Brentwood” were close copies of this popular Sears “Mitchell” model.

Sears’s plain one-story home, the “Winona,” was sold from 1913–40, more years than any other model. First known as model #205 and renamed Winona in 1917, it was updated in 1930 by the addition of a gabled dining room bay.

The Sears “Princeville” as it looked in the catalog.

This Sears “Princeville” model in St. Charles, Illinois, no longer bears any resemblance to its catalog image. It was located by means of a testimonial.

The cover of the 1923 Pacific Homes catalog was designed to appeal to the family of “modest means.”