IN ITS 1925 CATALOG, Aladdin Company stated: “The purpose of the Aladdin plan is to help builders of modest means.” Aladdin accurately targeted its audience: most purchasers were working class families, buying a single home for themselves. Although no nationwide studies have been conducted, trends revealed by in-depth studies in a few communities such as Elgin, Aurora, and Rockford in Illinois and Bay City, Flint, and Pontiac in Michigan support the premise that purchasers were indeed people of “modest means.” In the Elgin study, 37 percent of original owners were factory employees and 22 percent worked in construction trades. Only 0.02 percent were professionals.

From 1906–20, many buyers were farmers. But with the population shift to urban areas and the growth of suburbs, commuting office and factory workers needed convenient housing. The scene was ripe for the precut mailorder home. Lower in cost and constructed more quickly than standard housing, mail-order homes sprang up in increasing numbers.

Perhaps the most ingenious scheme to attract buyers for suburban homes was that of Grover C. Elmore and his Poultry Farm Colony. Elmore, a Chicago entrepreneur, platted six subdivisions thirty miles southwest of Chicago in Tinley Park, all with double-length lots. He advertised a tempting package: the buyer would get the house model of their choice, a chicken coop, and a hundred chickens. Once the house was ready, the family would move out of polluted Chicago. The husband, using the new commuter rail service, could continue his employment in the city. Meanwhile, the wife and children would enjoy the fresh air and sunshine of Tinley Park. The wife could care for the chickens and gather their eggs. These she would sell, supposedly earning enough money to pay the mortgage on the house. All twenty-one of the identified mail-order homes in Tinley Park are in Elmore subdivisions, some with the chicken coop still in evidence on the back of the lot.

This Sterling “Miracle” was built in Sylvan Lake, Michigan. (Photograph by Dale Wolicki)

In its 1928 catalog, Harris Brothers offers two ways to build:

“1. Buy the materials for your Harris Plan-Cut Home at the low freight paid prices shown and build it yourself with the guidance of our easily read and readily understood blue print plans, itemized material list and construction details.

2. Select your Harris Plan-Cut Home and let us send you all the materials we furnish for its construction. Then secure a reliable builder in your locality, arrange a contract for construction and supervise the erection from start to finish as the work progresses.”

We will never know for sure what percentage of purchasers assembled their precut homes themselves. Most probably hired a contractor or carpenter, unless they had carpentry skills.

Some contractors specialized in putting up precut homes. To encourage this, Aladdin took out advertisements in building trade magazines, offering to refer customers and advising builders that they would select one carpenter in each city to handle their orders. Sears published a letter from Des Plaines, Illinois, contractors Elmer and Oscar Blume, who stated they had built 104 mail-order homes. Russell Byrum, a popular local builder, assembled most of the 127 known mail-order homes in Anderson, Indiana. Byrum put up homes primarily from Sears, but also a number from Aladdin and Gordon-Van Tine.

After discontinuing the Modern Homes catalogs in 1940, Sears developed the “Club Plan of home purchase”, working through contractors to produce tract housing. Cranford, New Jersey, was the experimental site for the first development, Sunny Acres. Construction of the 172 homes began in 1940. (Photograph courtesy of Sunny Acres Civic Association)

Sears applied “mass production methods to the marketing of complete homes” such as this example in a development of ninety-four homes in Sidney, New York. The homes in each development were sold prior to construction and built simultaneously. The purchaser was not permitted to make any modifications. (Photograph by Anna Blinn Cole)

Although contractors built most mail-order homes, some were, indeed, built by the homeowners themselves. Stories about people who built and lived in mail-order homes have been transmitted by oral tradition. Children whose parents assembled mail-order homes invariably report that their job was to sort the numbered precut lumber. In Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, owners of a 1933 Sears “Laurel” model were visited by a man whose grandfather built the house. He told them that it had been delivered to the back yard by train on a track that is no longer in use.

House plans for the 1940–42 Sears developments were drawn up by architect Randolph Evans of New York. Each house had four rooms and a bath, and an attic which could later be finished. This is one of thirty homes built on a single block in Elyria, Ohio.

The son of one of the original Harris Brothers, Samuel Harris, Jr., recalled in his memoirs that as an added enticement to buyers who were moving west to build and settle, Harris Brothers allowed them to camp out with their families and livestock on the company premises while the materials for their homes were being loaded. When the train was ready to depart, the buyers rode on the boxcars with their new homes.

After World War I, a nationwide housing shortage induced employers to build or subsidize industrial housing, hoping to attract and keep good factory workers or miners. Large tracts of company-built housing became known as “company towns.”

All the major producers of mail-order housing, except Montgomery Ward, at one time or another offered industrial housing. A typical company town contained a limited number of home styles, giving the community a homogeneous appearance. For example, the 152 Sears homes put up in 1917 in Carlinville, Illinois, for Standard Oil Company coal miners included only eight models, with some minor changes to give variety to the neighborhood.

This Sears model #119 was built in 1913 by Peter Larson on a farm in Eagle Grove, Iowa. In 2008, it was purchased at a farm auction and can be seen on the move to nearby Ware, Iowa. (Photograph by Jane Hartsock)

The 252 Aladdin homes built in Birmingham, England, by the Austin Motor Company as a “Garden Community” to house its factory workers consisted mostly of identical one-story homes with identical two-story homes on the corners of each block.

A few of the many employers known to have used mail-order homes for their company towns were:

• 1915: Dupont, Hopewell, Virginia, by Aladdin

• 1915: American Zinc and Chemical Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, by Gordon-Van Tine

• 1917: Inland Collieries, Detroit, Michigan, by Lewis

• 1918–21: General Motors, Flint, Michigan, by Sterling

• circa 1923: Southern Pacific Railroad, by Pacific Homes

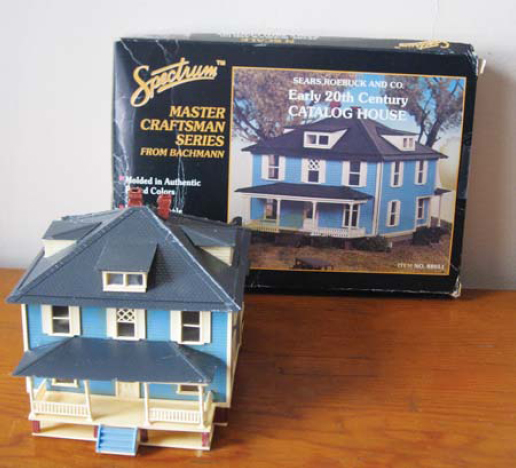

Bachmann Model Railroad Company copied this Sears American Foursquare style farmhouse. The Sears home was sold from 1908–18. Initially identified as model #102, in 1917 it was renamed the “Hamilton.”

To catch the interest of buyers, the cover of the 1925 Lewis catalog used the appellation “Homes of Character.”