THE KEY TO SUCCESS in any business is marketing the products and services offered. Mail-order home companies were no exception. The primary marketing campaign consisted of the catalogs themselves. Since these are the only remaining artifacts from the mail-order companies, it would be easy to assume that these are factual historical documents. Far from it! When perusing the past in catalogs, it is important to remember that these are advertising materials and probably have about as much credibility as today’s junk mail. Even in 1916, Gordon-Van Tine warned readers to beware of “tricky phrases” found in competitors’ guarantees.

All the catalogs detailed how much money could be saved and emphasized that buying directly from the mill avoided the profits of middlemen (architects and suppliers of lumber, millwork, roofing, paint, and hardware). The precut systems claimed to save the buyer anywhere from 25 to 50 percent of the cost of labor. To guarantee the quality of their lumber, Aladdin Company in 1917 promised to pay the customer one dollar for every knot found in the red cedar siding. Unarguably, precut homes did save the buyer money, and an examination of the homes themselves testifies to the high quality of the materials.

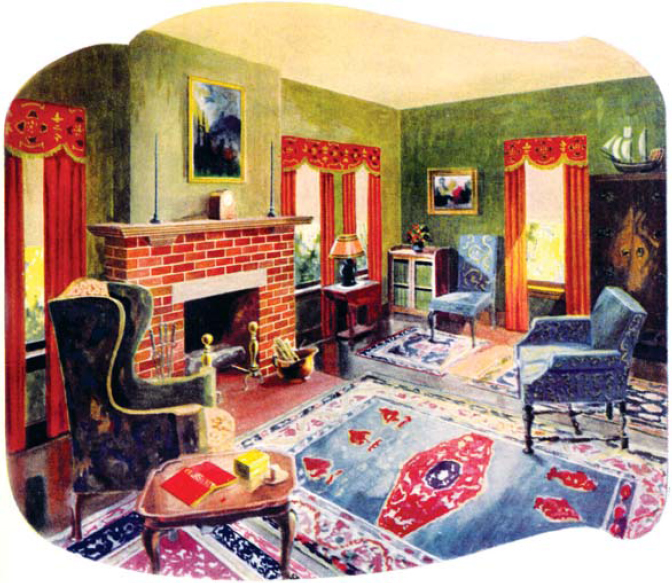

The catalogs also contained appealing but unsubstantiated descriptions of the homes, such as “Sterling Homes afford a thousand comforts and conveniences that ordinary plans cannot include.” Pictures of interiors were included especially to entice the woman of the house, who, it was supposed, would be less interested in construction details.

Most mail-order home suppliers sold different types of merchandise in other catalogs, thus, cross-marketing was a useful tool. In its 1929 publication Honor Bilt Modern Homes, Sears reminded homebuyers that “behind every Honor Bilt house stands the guarantee of the World’s Largest Store. We sell 35,000 different articles. We want to help you furnish that home.” Often, a few house catalog pages are devoted to items available at extra cost. The Aladdin 1925 catalog lists as extras special doors, grade cellar entrance, cellar windows, foundation posts, and green slate surfaced shingles. Aladdin advised readers to “send for the complete merchandise catalog,” which included heating, lighting and plumbing fixtures, and cabinetry. All the Sears specialty and general merchandise catalogs suggested obtaining the Modern Homes catalogs—for free, of course.

Hardware was not unique to a single company, except for this doorknob marked with the Aladdin logo, which entailed extra cost and so was not ordered by all purchasers.

Mail-order companies placed advertisements in leading popular magazines, such as National Geographic, Better Homes and Gardens, and Farm Journal, encouraging readers to send for their latest house catalogs.

To continually attract new customers, companies offered special deals. Usually, the buyer paid the freight, but from 1925–29, Aladdin stated “we pay the freight.” Chicago-based Harris Brothers, in 1928, also advised “We pay the freight to Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and western Pennsylvania.” Perhaps these were attempts to take business from Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, which were enticing buyers by offering mortgage financing.

In an effort to appeal especially to the woman of the family, Gordon-Van Tine catalogs included color plates showing interior views.

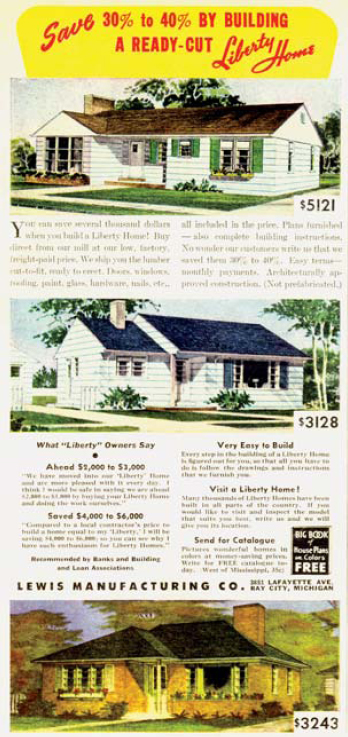

This advertisement for Lewis/Liberty homes, torn out of a Farm Journal magazine, was found tucked into a 1935 Gordon-Van Tine catalog, showing that buyers compared products.

Even the names of the companies themselves were used as marketing tools. Company names such as “Aladdin” and “Sterling” clearly were intended to appeal to customers. Model names also could evoke positive emotional responses. In 1920, Sterling models included the “Winsome,” the “Miracle,” and the “Charmcote.” In reality, these homes with charming names had no more curb appeal than the similar Harris Brothers’ models known as #1018, #1025, and #60.

Homes named after states and large towns might attract buyers from those locations. In 1917, Aladdin models included “Albany,” “Detroit,” “Burbank,” “Charleston,” and “Tucson.” Some Lewis names from 1917 have a more international appeal: “Alameda,” “Alpine,” “Cadiz,” and “El Dorado.”

When Montgomery Ward began subcontracting its homes from Gordon-Van Tine, they marketed their own designs as well as renamed Gordon-Van Tine models. Later, as these two companies sought to update their catalogs, they simply renamed the same old models in keeping with current fashion in real estate. The Gordon-Van Tine #613 (1924–28) became the “Redwood” in 1929 and the “Emerson” in 1932. Montgomery Ward sold the same house as the “Dresden” (1924–28) and the “Webster” (1929–31). Thus, it is possible that a single house design may bear a model number plus up to five different names. To add to the confusion, Lewis in 1917 named one of its homes the “Sterling.”

And, of course, companies used names from their competitors’ catalogs. In fact, aficionados of mail-order homes sometimes are confused by models from different companies with the same name that look nothing like each other.

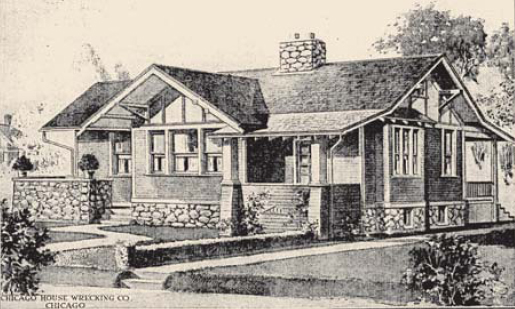

The 1920 Sterling “Charmcote” is certainly designed to charm with its many windows and inviting porch.

Sears and Gordon-Van Tine liberally sprinkled their mail-order home catalog pages with comments and letters from satisfied customers. The 1927 Gordon-Van Tine catalog has a testimonial on nearly every page. Montgomery Ward, especially in later years, included numerous letters of praise in the catalogs. In addition, Sears, Roebuck (1912–14), Gordon-Van Tine (1927), and Montgomery Ward (1931) each printed an entire booklet of nothing but testimonials from all over the country, including many photographs of completed homes. Of course, they never printed the communications from customers with grievances.

Rather than use catalog space to print testimonials, Pacific Homes contented themselves with this 1918 statement: “When you come to our office, we will be glad to show you any number of letters from customers.” The Bay City companies also tended to avoid cluttering the catalogs with notes from satisfied buyers. Harris Brothers included testimonials in their catalogs and also advised readers to request a folder of letters from their own state.

Harris’s #60 is nearly identical to the “Charmcote” and appears even more charming.

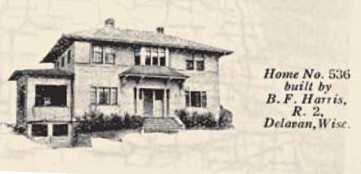

This Gordon-Van Tine testimonial includes a photograph of a finished Model #535 built in Delevan, Wisconsin.

Testimonials are a delight to historical architectural researchers as they provide, if not street addresses, at least model names, city and state locations, and often names of buyers. This information can be used to find the houses. Much research is in fact devoted to locating homes, and since only Aladdin preserved its sales records, testimonials for the other companies provide the only primary information available.

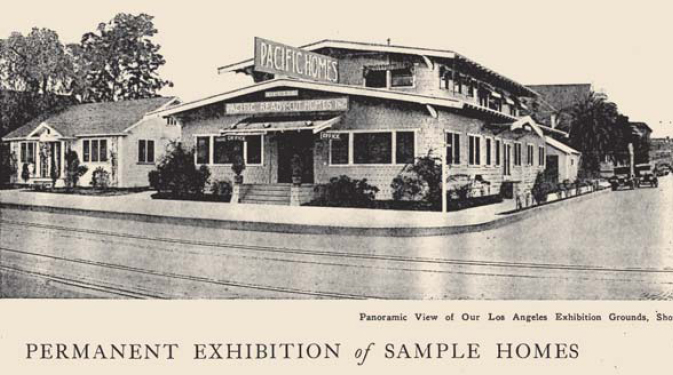

Print advertising is all well and good, but what if customers could actually see completed homes before making a selection? With that in mind, two companies built permanent display models, and others featured homes at national and regional fairs. Aladdin built examples of most of its homes in Bay City. Visitors to the company offices were given the addresses so they could view them. Pacific Homes put up a permanent exhibition of sample homes at 1220 South Hill Street, Los Angeles. Harris exhibited sectional buildings at their Chicago plant. Sears had a large showroom of building materials, but no complete homes, at its Chicago headquarters.

The Pacific Homes office and all its model homes, advertised in the 1923 catalog, are no longer standing.

To advertise his company’s wares, Aladdin chief executive William Sovereign lived in this modified “Villa” model in Bay City, Michigan, from 1922–68. (Photograph by Dale Wolicki)

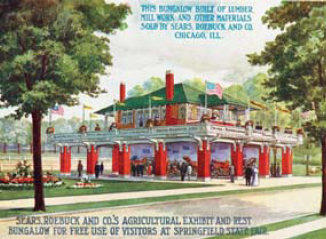

Aladdin Company erected its “Ideal” cottage at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California. Sears built two replicas of George Washington’s home, Mount Vernon: one for the 1931 Paris World’s Fair and the second for the Washington Bicentennial Celebration in Brooklyn, New York. Warner Brothers Picture Corporation chose Sears to build a “dream home” for a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, advertising campaign.

Over the years, mail-order home companies offered mortgage financing in order to take business from competitors whose terms were cash on delivery. The first was Sterling, which, in 1916, offered “Wide-Open Credit:” the buyer could pay half down, with the remainder distributed over two years in monthly payments.

In 1917, Sears initiated mortgage financing and soon discovered that the mortgage business was even more profitable than the housing business. Montgomery Ward entered the mortgage business in 1926 and by 1929 claimed that 95 percent of its homebuyers were taking advantage of this program. In 1938, Lewis/Liberty boosted orders by introducing a mortgage program approved by the Federal Housing Authority.

The large Sears pavilion at the 1910 Illinois State Fair, displaying Sears, Roebuck’s latest merchandise, was topped with a full-size example of model #151, the “Avondale.” (Postcard image courtesy of Lincoln Library, Springfield, Illinois)

The Montgomery Ward credit application was a model of simplicity, asking only a few questions: Do you own the lot? How much unpaid? What utilities? How much cash do you have? How much can you pay each month? What work can you do yourself? Occupation was requested, but it apparently was not important whether the applicant was actually employed. Mortgage payments could be as low as $20 per month. Loans typically were made for a term of five to fifteen years.

Gordon-Van Tine offered financing on a very limited basis from 1924–31, apparently only in the Davenport, Iowa, area. Pacific Homes offered no financing, but suggested that their financial department would be able to assist homebuilders in negotiating bank loans.

In 1928, Harris Brothers offered “most liberal terms:” no cash in advance with five days’ inspection time allowed before payment, a 2 percent discount if one quarter of the total was paid with the order, or a 5 percent discount for advance payment in full.

Financially conservative Aladdin’s terms were a down payment with the order and the balance COD. This lasted until the 1960s, when they offered two payment plans: send full cash with the order and deduct 2 percent or pay 10 percent with the order and the balance within six months after shipment.

Mortgages to mail-order companies most typically are found in larger urban areas, especially those where mail-order company sales offices were located. Mortgages seldom were found in small towns, where the preference was for local financing.

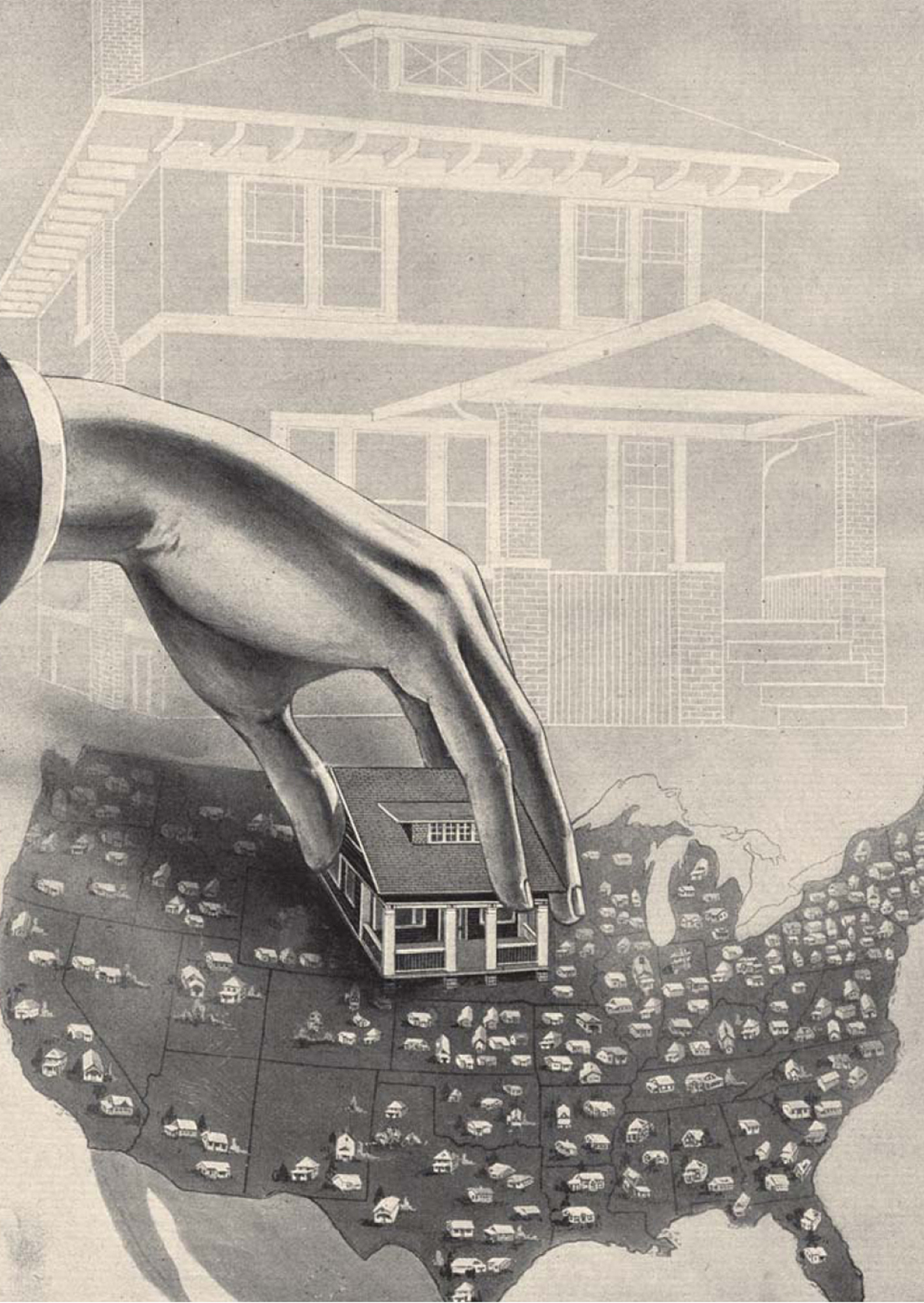

Mail-order companies sought to improve their credibility by boasting about total sales. Most of these claims are deliberately vague and easily open to misinterpretation.

For example, during its second year of selling homes, Aladdin advertised that “We have sold these homes to hundreds of business men, professional men and farmers.” Of course, this begs the question of how many hundreds. In 1925, Aladdin mentioned that “tens of thousands of Americans live in Aladdin homes.” Is this the same as saying ten thousand homes have been sold? Of course not: several people typically occupied each home. But readers of the catalog would remember the number “ten thousand” and suppose that was the number of homes sold.

This Sears sales office model of the “Puritan” was discovered on eBay advertised as a dollhouse. (Photograph by Dale Wolicki)

Books published since 1986 state that Sears sold 100,000 homes. However, sales figures do not support this claim. Sears does bandy about the number 100,000, but a careful reading of various catalogs reveals that Sears does not claim to have built 100,000 homes. In 1934, the catalog said “more than 100,000 homes have been built the Sears way.” But what was the “Sears way” exactly?

Sterling Company’s 1916 catalog graphically demonstrates the company’s nationwide delivery system.