BY THE LATE 1920S, mail-order homes were securely established as an affordable way to build new homes. The evolution of commuter rail lines created suburbs on the edges of major urban centers, and the new commuter class was a ready-made market for precut kit manufacturers.

Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward reported their highest home sales in the year 1929. With no idea of the length and depth of the impending Great Depression, mail-order home companies continued to produce new catalogs after the stock market crash of October 29, 1929, presenting new designs embodying the increasingly popular Tudor and Colonial Revival styles.

Considered as a whole, the eight major mail-order home companies had achieved truly nationwide distribution capabilities. Lewis had mills in Bay City, Michigan; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; Jacksonville, Florida; and Bristol, Tennessee. In 1927, Gordon-Van Tine listed as locations Davenport, Iowa; Chehallis, Washington; St. Louis, Missouri; and Hattiesburg, Mississippi. On the back cover of its 1928 catalog, Montgomery Ward listed several sales office locations: Chicago; Kansas City, Missouri; St. Paul, Minnesota; Baltimore, Maryland; Oakland, California; and Fort Worth, Texas. By 1929, Sears, Roebuck had established a total of sixty-five Modern Homes sales offices in thirteen states and Washington, D.C.

Companies and contractors sometimes built speculation models of mailorder homes in new housing developments. This strategy certainly would have brought a large number of sales, but for the intervention of the Great Depression. By 1931, the spreading ripples of the stock market crash had devastating effects on housing in the United States. New housing starts were down 52 percent from 1929. Acres of newly platted developments in cities and towns sat empty of houses.

Mail-order home producers certainly were not immune to the disastrous economic effects of the Great Depression. In 1931, Montgomery Ward permanently closed its housing division. By 1932, Harris Brothers offered only a handful of precut homes and farm buildings in its general merchandise catalogs. In spring 1933, Sears, Roebuck closed its Modern Homes Division after suffering a loss of more than $8 million in uncollectible mortgages. Although the Modern Homes Division reopened in autumn 1933 offering fewer designs and no mortgage financing, sales never again reached the former profitability, and the division finally closed for good in 1940.

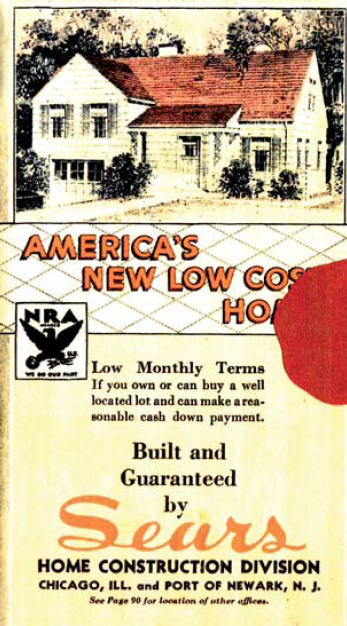

The damaged cover of Sears, Roebuck’s 1934 catalog bears the National Recovery Act logo.

F. K. Wheeler, plant manager of the Sears, Roebuck lumber mill in Cairo, Illinois, from 1925–56, wrote that the mill worked “on Sears orders almost exclusively” until the financial crash of 1929 when Sears “virtually stopped selling houses.” The mill then turned to making crates and selling bulk lumber. In 1937, they received a government contract for eighteen prefabricated Civilian Conservation Corps camps. In 1940, Sears, Roebuck sold the plant.

Mail-order home companies employed cost-saving measures such as printing separate price sheets, enabling them to adjust prices without the expense of designing and printing an entire new catalog. The Sears, Roebuck Fall 1933 and Spring 1934 catalogs were reduced to half-size pages in order to save on printing costs.

Desperate to remain in business, mail-order home producers explored new marketing strategies. In an effort to reach buyers in a higher economic class, Sears, Roebuck and Gordon-Van Tine began to offer custom design services. “We will prepare a home plan for you FREE,” offered Gordon-Van Tine in 1932. “We will take your ideas from photograph, picture, rough pencil sketch or just a written description and develop a plan.” In the 1933 publication America’s New Low Cost Homes, Sears, Roebuck offered to build “from any plans you already have, or from plans prepared by your own architect.”

In 1932, Gordon-Van Tine introduced its “Master Plan” homes, a series of homes with the same floor plan but slightly altered exterior appearance. This was a cost-saving strategy for the company, decreasing the architect’s fees and allowing most of the lumber to be standardized.

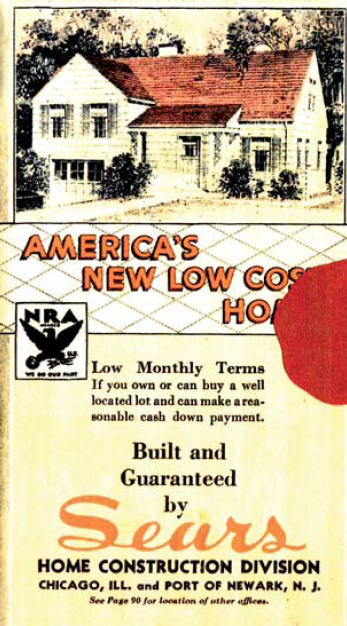

The Sears, Roebuck 1932 catalog featured photographs of six custom models, including this handsome Anderson, Indiana, home.

No mail-order home company was able to survive the Great Depression solely by selling houses. All opted for strategies such as securing Civilian Conservation Corps contracts, selling pallets and packing crates, and concentrating on sales of bulk lumber and building materials.

Purchasing plans and bulk materials instead of precut lumber had always been a money-saving option for mail-order homes. For example, the four-room Sears “Dundee” model was offered in 1921 for $1,138 already cut, and for $831 not cut and fitted, a savings of 27 percent.

During the 1930s, as evidenced by the higher percentage of homes lacking part numbers, it appears that a larger number of purchasers chose this cheaper option. As shown in the table below, the decrease in total number of models offered each year graphically depicts the challenges faced by mail-order home companies:

| Company | 1928–29 | 1938–39 |

| Sears | 82 | 39 |

| Gordon-Van Tine | 83 | 41 |

| Harris Brothers | 95 | 0 |

| Montgomery Ward | 62 | 0 |

| Aladdin | 30 | 43 |

| Lewis | 20 | 25 |

| Sterling | 35 | 35 |

| TOTALS | 407 | 183 |

In 1930, an Elgin, Illinois, resident decided to build himself a new home on the vacant lot he owned next door. He built this Sears, Roebuck “Strathmore” model, a substantial two-story Tudor Revival home. By the time he finished construction in 1933, however, he could not afford the home and was forced to sell it before he ever moved in.

During the Great Depression, thousands of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward houses were repossessed nationwide even though determined homeowners did all they could to avoid losing their homes. In an Elgin, Illinois, study, the son the original owner of a modest Sears, Roebuck five-room “Rodessa” model reported that his family was able to keep the house only because the bank agreed to accept payments of interest only. His mother went to work at the local five-and-ten store in order to save the house.

The Elgin owners of a three-bedroom Sears, Roebuck “Lynnhaven” model kept their house by renting the upstairs to another family. The parents then slept in the dining room, and their son slept in the breakfast nook. And five of Matthew Warner’s six sons were able to keep the Sears, Roebuck homes they built because a wealthy relative was willing to hold the mortgages on all five properties. One of the Warner children remembers trudging down a dusty country road south of Elgin to bring the monthly payment to the relative’s farm. Another family ordered a Gordon-Van Tine home. When it arrived, the buyer determined he could use the lumber intended for one house to build two homes by spacing boards farther apart and making a few other changes.

The Minimal Traditional Sears “Carver” in West Chicago, Illinois, has no decorative detail.

No sooner had the United States achieved a measure of recovery from the Great Depression than the country entered World War II, further depressing the market for new homes. Mail-order home companies tried to survive the war by building army barracks and making packing crates.

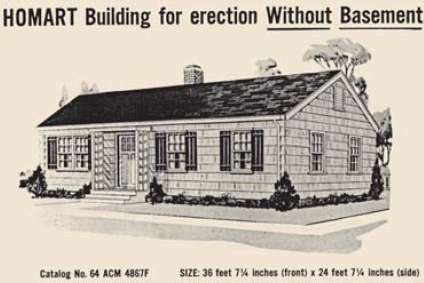

In 1949, Sears reentered the housing market with twelve prefabricated sectional models using the brand name “Homart” (from Homan and Arthington streets where the main Chicago office was located). The Minimal Traditional homes were so lacking in architectural detail as to appear institutional. The construction details were similar to the sectional cottages offered by Sears, Roebuck, Harris Brothers, and Gordon-Van Tine prior to World War I. Available either with or without a basement, they consisted of four-foot wide preconstructed panels that could be bolted together at the building site, quickly providing basic housing at minimal cost.

Perhaps this idea would have met with more success a few years earlier, when, under subsidies from the U.S. Government, numerous companies offered prefabricated homes to meet the immediate postwar housing needs. However, low sales of Homart models are evidenced by the small number of these homes that have been located to date, as well as by the discontinuation of these models by 1952.

A Sears, Roebuck “Homart” model as shown in the 1951 catalog.

By 1950, the nearly 13 million servicemen and women who had returned from the war with the dream of raising their families in peace desired new homes. They wanted something new and possessed sufficient funds to invest in better housing.

With the return of prosperity, architects took a new direction in design: the Western Ranch style. Like other architectural styles, it has roots in the past, representing a revival of the nineteenth-century “rancho” homes built in the Southwest by Spanish-speaking settlers.

The one-story rambling plans characterized by a long, low profile became the most popular postwar house design. To add visual interest, architects used a variety of cladding materials such as cedar siding, brick, and Permastone, a type of simulated masonry. Massive chimneys were located centrally or on the front elevation, and a picture window was almost obligatory.

Mid-Century Modern took the country by storm. Due to increased automobile ownership, suburbs no longer were limited to the extent of commuter train, bus, or streetcar lines. The new suburbs offered large lots to accommodate ranch designs.

By the end of World War II, only three of the original mail-order home companies were still in business—Aladdin, Lewis/Liberty, and Sterling—all headquartered in Bay City, Michigan. In the face of increasing competition from makers of prefabricated housing, the Bay City companies continued to do what they knew best: produce precut homes. The cover of the 1954 Aladdin catalog pointed out that the Readi-Cut homes were not prefabricated.

The cover of Sterling’s 1948 catalog foreshadowed the new, soon-to-be dominant Western Ranch designs; however, most of the homes in this catalog were Minimal Traditional designs.

Of course, the designs of mail-order homes followed popular trends. Typically, providers of precut homes were cautious about abandoning the tried and true, best-seller models of the past. Although Aladdin’s 1948 catalog featured the “Palm Springs” Western Ranch on the cover, it offered only one additional ranch design; the remainder of the catalog consisted of more traditional homes, many continued from earlier catalogs. As it became clear that the ranch was here to stay, mail-order home catalogs contained increasing numbers of ranch models.

Waunakee, Wisconsin, is the home of this Aladdin “Alamo” model. Note the different heights of roof sections, emphasizing the horizontal line.

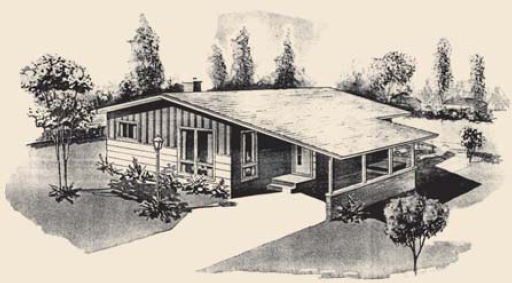

The Mid-Century Modern Contemporary Style, with its front-facing gable, asymmetrical roof, and angular lines was uncommon in mail-order catalogs. Lewis/Liberty offered this “Carlton” model in 1962–63.

In the mid-1950s and 1960s, Sears, Roebuck again entered the housing market, offering models under the tradename Homart. No catalogs advertising these have been unearthed as of 2010. Blueprints bear the names Homart and Sears, Roebuck but do not indicate whether the buildings were prefabricated, built from kits, or built by standard construction.

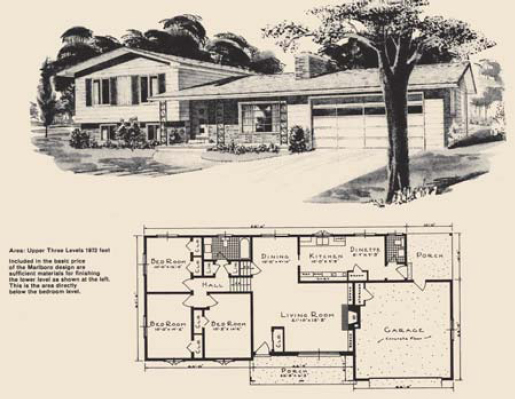

As land gradually became more scarce and costly, ranch designers developed split-level and two-story versions of the new style. An attached garage became a standard feature on larger models. The main mail-order home enthusiasts of the new styles were Aladdin and Lewis/Liberty; Sterling never embraced the ranch home to the same extent, offering only one-story models and continuing to market Minimal Traditional designs through 1974.

This 1954 Minimal Traditional concrete block Sears, Roebuck Homart home in Warrenville, Illinois, complete with blueprints, is so far the only known example of its kind.

The conservative Sterling 1971 “Graystone” was designed “with an eye toward economy and yet embodying that modernistic trend.”

A row of three identical 1965 Sears Homart models stands in the 3400 block of North Pittsburg Street in Chicago. These bungalows were designed to fit on a narrow city lot.

Lewis/Liberty’s 1962 “Marlboro” is a cross-gabled home that blends “the beauty of the ranch house and the flair and compactness of the split-level.”