2

RATIONALITY AND IRRATIONALITY

May I say that I have not thoroughly enjoyed serving with humans? I find their illogic and foolish emotions a constant irritant.

—Mr. Spock

Rationality is uncool. To describe someone with a slang word for the cerebral, like nerd, wonk, geek, or brainiac, is to imply they are terminally challenged in hipness. For decades, Hollywood screenplays and rock song lyrics have equated joy and freedom with an escape from reason. “A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free,” said Zorba the Greek. “Stop making sense,” advised Talking Heads; “Let’s go crazy,” adjured the Artist Formerly Known as Prince. Fashionable academic movements like postmodernism and critical theory (not to be confused with critical thinking) hold that reason, truth, and objectivity are social constructions that justify the privilege of dominant groups. These movements have an air of sophistication about them, implying that Western philosophy and science are provincial, old-fashioned, naïve to the diversity of ways of knowing found across periods and cultures. To be sure, not far from where I live in downtown Boston there is a splendid turquoise and gold mosaic that proclaims, “Follow reason.” But it is affixed to the Grand Lodge of the Masons, the fez- and apron-sporting fraternal organization that is the answer to the question “What’s the opposite of hip?”

My own position on rationality is “I’m for it.” Though I cannot argue that reason is dope, phat, chill, fly, sick, or da bomb, and strictly speaking I cannot even justify or rationalize reason, I will defend the message on the mosaic: we ought to follow reason.

Reasons for Reason

To begin at the beginning: what is rationality? As with most words in common usage, no definition can stipulate its meaning exactly, and the dictionary just leads us in a circle: most define rational as “having reason,” but reason itself comes from the Latin ration-, often defined as “reason.”

A definition that is more or less faithful to the way the word is used is “the ability to use knowledge to attain goals.” Knowledge in turn is standardly defined as “justified true belief.”1 We would not credit someone with being rational if they acted on beliefs that were known to be false, such as looking for their keys in a place they knew the keys could not be, or if those beliefs could not be justified—if they came, say, from a drug-induced vision or a hallucinated voice rather than observation of the world or inference from some other true belief.

The beliefs, moreover, must be held in service of a goal. No one gets rationality credit for merely thinking true thoughts, like calculating the digits of π or cranking out the logical implications of a proposition (“Either 1 + 1 = 2 or the moon is made of cheese,” “If 1 + 1 = 3, then pigs can fly”). A rational agent must have a goal, whether it is to ascertain the truth of a noteworthy idea, called theoretical reason, or to bring about a noteworthy outcome in the world, called practical reason (“what is true” and “what to do”). Even the humdrum rationality of seeing rather than hallucinating is in the service of the ever-present goal built into our visual systems of knowing our surroundings.

A rational agent, moreover, must attain that goal not by doing something that just happens to work there and then, but by using whatever knowledge is applicable to the circumstances. Here is how William James distinguished a rational entity from a nonrational one that would at first appear to be doing the same thing:

Romeo wants Juliet as the filings want the magnet; and if no obstacles intervene he moves toward her by as straight a line as they. But Romeo and Juliet, if a wall be built between them, do not remain idiotically pressing their faces against its opposite sides like the magnet and the filings with the card. Romeo soon finds a circuitous way, by scaling the wall or otherwise, of touching Juliet’s lips directly. With the filings the path is fixed; whether it reaches the end depends on accidents. With the lover it is the end which is fixed; the path may be modified indefinitely.2

With this definition the case for rationality seems all too obvious: do you want things or don’t you? If you do, rationality is what allows you to get them.

Now, this case for rationality is open to an objection. It advises us to ground our beliefs in the truth, to ensure that our inference from one belief to another is justified, and to make plans that are likely to bring about a given end. But that only raises further questions. What is “truth”? What makes an inference “justified”? How do we know that means can be found that really do bring about a given end? But the quest to provide the ultimate, absolute, final reason for reason is a fool’s errand. Just as an inquisitive three-year-old will reply to every answer to a “why” question with another “Why?,” the quest to find the ultimate reason for reason can always be stymied by a demand to provide a reason for the reason for the reason. Just because I believe P implies Q, and I believe P, why should I believe Q? Is it because I also believe [(P implies Q) and P] implies Q? But why should I believe that? Is it because I have still another belief, {[(P implies Q) and P] implies Q} implies Q?

This regress was the basis for Lewis Carroll’s 1895 story “What the Tortoise Said to Achilles,” which imagined the conversation that would unfold when the fleet-footed warrior caught up to (but could never overtake) the tortoise with the head start in Zeno’s second paradox. (In the time it took for Achilles to close the gap, the tortoise moved on, opening up a new gap for Achilles to close, ad infinitum.) Carroll was a logician as well as a children’s author, and in this article, published in the philosophy journal Mind, he imagines the warrior seated on the tortoise’s back and responding to the tortoise’s escalating demands to justify his arguments by filling up a notebook with thousands of rules for rules for rules.3 The moral is that reasoning with logical rules at some point must simply be executed by a mechanism that is hardwired into the machine or brain and runs because that’s how the circuitry works, not because it consults a rule telling it what to do. We program apps into a computer, but its CPU is not itself an app; it’s a piece of silicon in which elementary operations like comparing symbols and adding numbers have been burned. Those operations are designed (by an engineer, or in the case of the brain by natural selection) to implement laws of logic and mathematics that are inherent to the abstract realm of ideas.4

Now, Mr. Spock notwithstanding, logic is not the same thing as reasoning, and in the next chapter we’ll explore the differences. But they are closely related, and the reasons the rules of logic can’t be executed by still more rules of logic (ad infinitum) also apply to the justification of reason by still more reason. In each case the ultimate rule has to be “Just do it.” At the end of the day the discussants have no choice but to commit to reason, because that’s what they committed themselves to at the beginning of the day, when they opened up a discussion of why we should follow reason. As long as people are arguing and persuading and then evaluating and accepting or rejecting the arguments—as opposed to, say, bribing or threatening each other into mouthing some words—it’s too late to ask about the value of reason. They’re already reasoning, and have tacitly accepted its value.

When it comes to arguing against reason, as soon as you show up, you lose. Let’s say you argue that rationality is unnecessary. Is that statement rational? If you concede it isn’t, then there’s no reason for me to believe it—you just said so yourself. But if you insist I must believe it because the statement is rationally compelling, you’ve conceded that rationality is the measure by which we should accept beliefs, in which case that particular one must be false. In a similar way, if you were to claim that everything is subjective, I could ask, “Is that statement subjective?” If it is, then you are free to believe it, but I don’t have to. Or suppose you claim that everything is relative. Is that statement relative? If it is, then it may be true for you right here and now but not for anyone else or after you’ve stopped talking. This is also why the recent cliché that we’re living in a “post-truth era” cannot be true. If it were true, then it would not be true, because it would be asserting something true about the era in which we are living.

This argument, laid out by the philosopher Thomas Nagel in The Last Word, is admittedly unconventional, as any argument about argument itself would have to be.5 Nagel compared it to Descartes’s argument that our own existence is the one thing we cannot doubt, because the very fact of wondering whether we exist presupposes the existence of a wonderer. The very fact of interrogating the concept of reason using reason presupposes the validity of reason. Because of this unconventionality, it’s not quite right to say that we should “believe in” reason or “have faith in” reason. As Nagel points out, that’s “one thought too many.” The masons (and the Masons) got it right: we should follow reason.

Now, arguments for truth, objectivity, and reason may stick in the craw, because they seem dangerously arrogant: “Who the hell are you to claim to have the absolute truth?” But that’s not what the case for rationality is about. The psychologist David Myers has said that the essence of monotheistic belief is: (1) There is a God and (2) it’s not me (and it’s also not you).6 The secular equivalent is: (1) There is objective truth and (2) I don’t know it (and neither do you). The same epistemic humility applies to the rationality that leads to truth. Perfect rationality and objective truth are aspirations that no mortal can ever claim to have attained. But the conviction that they are out there licenses us to develop rules we can all abide by that allow us to approach the truth collectively in ways that are impossible for any of us individually.

The rules are designed to sideline the biases that get in the way of rationality: the cognitive illusions built into human nature, and the bigotries, prejudices, phobias, and -isms that infect the members of a race, class, gender, sexuality, or civilization. These rules include the principles of critical thinking and the normative systems of logic, probability, and empirical reasoning that will be explained in the chapters to come. They are implemented among flesh-and-blood people by social institutions that prevent people from imposing their egos or biases or delusions on everyone else. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” wrote James Madison about the checks and balances in a democratic government, and that is how other institutions steer communities of biased and ambition-addled people toward disinterested truth. Examples include the adversarial system in law, peer review in science, editing and fact-checking in journalism, academic freedom in universities, and freedom of speech in the public sphere. Disagreement is necessary in deliberations among mortals. As the saying goes, the more we disagree, the more chance there is that at least one of us is right.

Though we can never prove that reasoning is sound or the truth can be known (since we would need to assume the soundness of reason to do it), we can stoke our confidence that they are. When we apply reason to reason itself, we find that it is not just an inarticulate gut impulse, a mysterious oracle that whispers truths into our ear. We can expose the rules of reason and distill and purify them into normative models of logic and probability. We can even implement them in machines that duplicate and exceed our own rational powers. Computers are literally mechanized logic, their smallest circuits called logic gates.

Another reassurance that reason is valid is that it works. Life is not a dream, in which we pop up in disconnected locations and bewildering things happen without rhyme or reason. By scaling the wall, Romeo really does get to touch Juliet’s lips. And by deploying reason in other ways, we reach the moon, invent smartphones, and extinguish smallpox. The cooperativeness of the world when we apply reason to it is a strong indication that rationality really does get at objective truths.

And ultimately even relativists who deny the possibility of objective truth and insist that all claims are merely the narratives of a culture lack the courage of their convictions. The cultural anthropologists or literary scholars who avow that the truths of science are merely the narratives of one culture will still have their child’s infection treated with antibiotics prescribed by a physician rather than a healing song performed by a shaman. And though relativism is often adorned with a moral halo, the moral convictions of relativists depend on a commitment to objective truth. Was slavery a myth? Was the Holocaust just one of many possible narratives? Is climate change a social construction? Or are the suffering and danger that define these events really real—claims that we know are true because of logic and evidence and objective scholarship? Now relativists stop being so relative.

For the same reason there can be no tradeoff between rationality and social justice or any other moral or political cause. The quest for social justice begins with the belief that certain groups are oppressed and others privileged. These are factual claims and may be mistaken (as advocates of social justice themselves insist in response to the claim that it’s straight white men who are oppressed). We affirm these beliefs because reason and evidence suggest they are true. And the quest in turn is guided by the belief that certain measures are necessary to rectify those injustices. Is leveling the playing field enough? Or have past injustices left some groups at a disadvantage that can only be set right by compensatory policies? Would particular measures merely be feel-good signaling that leaves the oppressed groups no better off? Would they make matters worse? Advocates of social justice need to know the answers to these questions, and reason is the only way we can know anything about anything.

Admittedly, the peculiar nature of the argument for reason always leaves open a loophole. In introducing the case for reason, I wrote, “As long as people are arguing and persuading . . . ,” but that’s a big “as long as.” Rationality rejecters can refuse to play the game. They can say, “I don’t have to justify my beliefs to you. Your demands for arguments and evidence show that you are part of the problem.” Instead of feeling any need to persuade, people who are certain they are correct can impose their beliefs by force. In theocracies and autocracies, authorities censor, imprison, exile, or burn those with the wrong opinions. In democracies the force is less brutish, but people still find means to impose a belief rather than argue for it. Modern universities—oddly enough, given that their mission is to evaluate ideas—have been at the forefront of finding ways to suppress opinions, including disinviting and drowning out speakers, removing controversial teachers from the classroom, revoking offers of jobs and support, expunging contentious articles from archives, and classifying differences of opinion as punishable harassment and discrimination.7 They respond as Ring Lardner recalled his father doing when the writer was a boy: “ ‘Shut up,’ he explained.”

If you know you are right, why should you try to persuade others through reason? Why not just strengthen solidarity within your coalition and mobilize it to fight for justice? One reason is that you would be inviting questions such as: Are you infallible? Are you certain that you’re right about everything? If so, what makes you different from your opponents, who also are certain they’re right? And from authorities throughout history who insisted they were right but who we now know were wrong? If you have to silence people who disagree with you, does that mean you have no good arguments for why they’re mistaken? The incriminating lack of answers to such questions could alienate those who have not taken sides, including the generations whose beliefs are not set in stone.

And another reason not to blow off persuasion is that you will have left those who disagree with you no choice but to join the game you are playing and counter you with force rather than argument. They may be stronger than you, if not now then at some time in the future. At that point, when you are the one who is canceled, it will be too late to claim that your views should be taken seriously because of their merits.

Stop Making Sense?

Must we always follow reason? Do I need a rational argument for why I should fall in love, cherish my children, enjoy the pleasures of life? Isn’t it sometimes OK to go crazy, to be silly, to stop making sense? If rationality is so great, why do we associate it with a dour joylessness? Was the philosophy professor in Tom Stoppard’s play Jumpers right in his response to the claim that “the Church is a monument to irrationality”?

The National Gallery is a monument to irrationality! Every concert hall is a monument to irrationality! And so is a nicely kept garden, or a lover’s favour, or a home for stray dogs! . . . If rationality were the criterion for things being allowed to exist, the world would be one gigantic field of soya beans!8

The rest of this chapter takes up the professor’s challenge. We will see that while beauty and love and kindness are not literally rational, they’re not exactly irrational, either. We can apply reason to our emotions and to our morals, and there is even a higher-order rationality that tells us when it can be rational to be irrational.

Stoppard’s professor may have been misled by David Hume’s famous argument that “reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”9 Hume, one of the hardest-headed philosophers in the history of Western thought, was not advising his readers to shoot from the hip, live for the moment, or fall head over heels for Mr. Wrong.10 He was making the logical point that reason is the means to an end, and cannot tell you what the end should be, or even that you must pursue it. By “passions” he was referring to the source of those ends: the likes, wants, drives, emotions, and feelings wired into us, without which reason would have no goals to figure out how to attain. It’s the distinction between thinking and wanting, between believing something you hold to be true and desiring something you wish to bring about. His point was closer to “There’s no disputing tastes” than “If it feels good, do it.”11 It is neither rational nor irrational to prefer chocolate ripple to maple walnut. And it is in no way irrational to keep a garden, fall in love, care for stray dogs, party like it’s 1999, or dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free.12

Still, the impression that reason can oppose the emotions must come from somewhere—surely it is not just a logical error. We keep our distance from hotheads, implore people to be reasonable, and regret various flings, outbursts, and acts of thoughtlessness. If Hume was right, how can the opposite of what he wrote also be true: that the passions must often be slaves to reason?

In fact, it’s not hard to reconcile them. One of our goals can be incompatible with the others. Our goal at one time can be incompatible with our goals at other times. And one person’s goals can be incompatible with others’. With those conflicts, it won’t do to say that we should serve and obey our passions. Something has to give, and that is when rationality must adjudicate. We call the first two applications of reason “wisdom” and the third one “morality.” Let’s look at each.

Conflicts among Goals

People don’t want just one thing. They want comfort and pleasure, but they also want health, the flourishing of their children, the esteem of their fellows, and a satisfying narrative on how they have lived their lives. Since these goals may be incompatible—cheesecake is fattening, unattended kids get into trouble, and cutthroat ambition earns contempt—you can’t always get what you want. Some goals are more important than others: the satisfaction deeper, the pleasure longer lasting, the narrative more compelling. We use our heads to prioritize our goals and pursue some at the expense of others.

Indeed, some of our apparent goals are not even really our goals—they are the metaphorical goals of our genes. The evolutionary process selects for genes that lead organisms to have as many surviving offspring as possible in the kinds of environments in which their ancestors lived. They do so by giving us motives like hunger, love, fear, comfort, sex, power, and status. Evolutionary psychologists call these motives “proximate,” meaning that they enter into our conscious experience and we deliberately try to carry them out. They can be contrasted with the “ultimate” motives of survival and reproduction, which are the figurative goals of our genes—what they would say they wanted if they could talk.13

Conflicts between proximate and ultimate goals play out in our lives as conflicts between different proximate goals. Lust for an attractive sexual partner is a proximate motive, whose ultimate motive is conceiving a child. We inherited it because our more lustful ancestors, on average, had more offspring. However, conceiving a child may not be among our proximate goals, and so we may deploy our reason to foil that ultimate goal by using contraception. Having a trusted romantic partner we don’t betray and maintaining the respect of our peers are other proximate goals, which our rational faculties may pursue by advising our not-so-rational faculties to avoid dangerous liaisons. In a similar way we pursue the proximate goal of a slim, healthy body by overriding another proximate goal, a delicious dessert, which itself arose from the ultimate goal of hoarding calories in an energy-stingy environment.

When we say someone’s acting emotionally or irrationally, we’re often alluding to bad choices in these tradeoffs. It often feels great in the heat of the moment to blow your stack when someone has crossed you. But our cooler head may realize that it’s better to put a lid on it, to achieve things that make us feel even greater in the long run, like a good reputation and a trusting relationship.

Conflicts among Time Frames

Since not everything happens at once, conflicts between goals often involve goals that are realized at different times. And these in turn often feel like conflicts between different selves, a present self and a future self.14

The psychologist Walter Mischel captured the conflict in an agonizing choice he gave four-year-olds in a famous 1972 experiment: one marshmallow now or two marshmallows in fifteen minutes.15 Life is a never-ending gantlet of marshmallow tests, dilemmas that force us to choose between a sooner small reward and a later large reward. Watch a movie now or pass a course later; buy a bauble now or pay the rent later; enjoy five minutes of fellatio now or an unblemished record in the history books later.

The marshmallow dilemma goes by several names, including self-control, delay of gratification, time preference, and discounting the future.16 It figures into any analysis of rationality because it helps explain the misconception that too much rationality makes for a cramped and dreary life. Economists have studied the normative grounds for self-control—when we ought to indulge now or hold off for later—since it is the basis for interest rates, which compensate people for giving up money now in exchange for money later. They have reminded us that often the rational choice is to indulge now: it all depends on when and how much. In fact this conclusion is already a part of our folk wisdom, captured in aphorisms and jokes.

First, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. How do you know that the experimenter will keep his promise and reward you for your patience with two marshmallows when the time comes? How do you know that the pension fund will still be solvent when you retire and the money you have put away for retirement will be available when you need it? It’s not just the imperfect integrity of trustees that can punish delay of gratification; it’s the imperfect knowledge of experts. “Everything they said was bad for you is good for you,” we joke, and with today’s better nutrition science we know that a lot of pleasure from eggs, shrimp, and nuts was forgone in past decades for no good reason.

Second, in the long run we’re all dead. You could be struck by lightning tomorrow, in which case all the pleasure you deferred to next week, next year, or next decade will have gone to waste. As the bumper sticker advises, “Life is short. Eat dessert first.”

Third, you’re only young once. It may cost more overall to take out a mortgage in your thirties than to save up and pay cash for a house in your eighties, but with the mortgage you get to live in it all those years. And the years are not just more numerous but different. As my doctor once said to me after a hearing test, “The great tragedy in life is that when you’re old enough to afford really good audio equipment, you can’t hear the difference.” This cartoon makes a similar point:

These arguments are combined in a story. A man is sentenced to be hanged for offending the sultan, and offers a deal to the court: if they give him a year, he will teach the sultan’s horse to sing, earning his freedom. When he returns to the dock, a fellow prisoner says, “Are you crazy? You’re only postponing the inevitable. In a year there will be hell to pay.” The man replies, “I figure over a year, a lot can happen. Maybe the sultan will die, and the new sultan will pardon me. Maybe I’ll die; in that case I would have lost nothing. Maybe the horse will die; then I’ll be off the hook. And who knows? Maybe I’ll teach the horse to sing!”

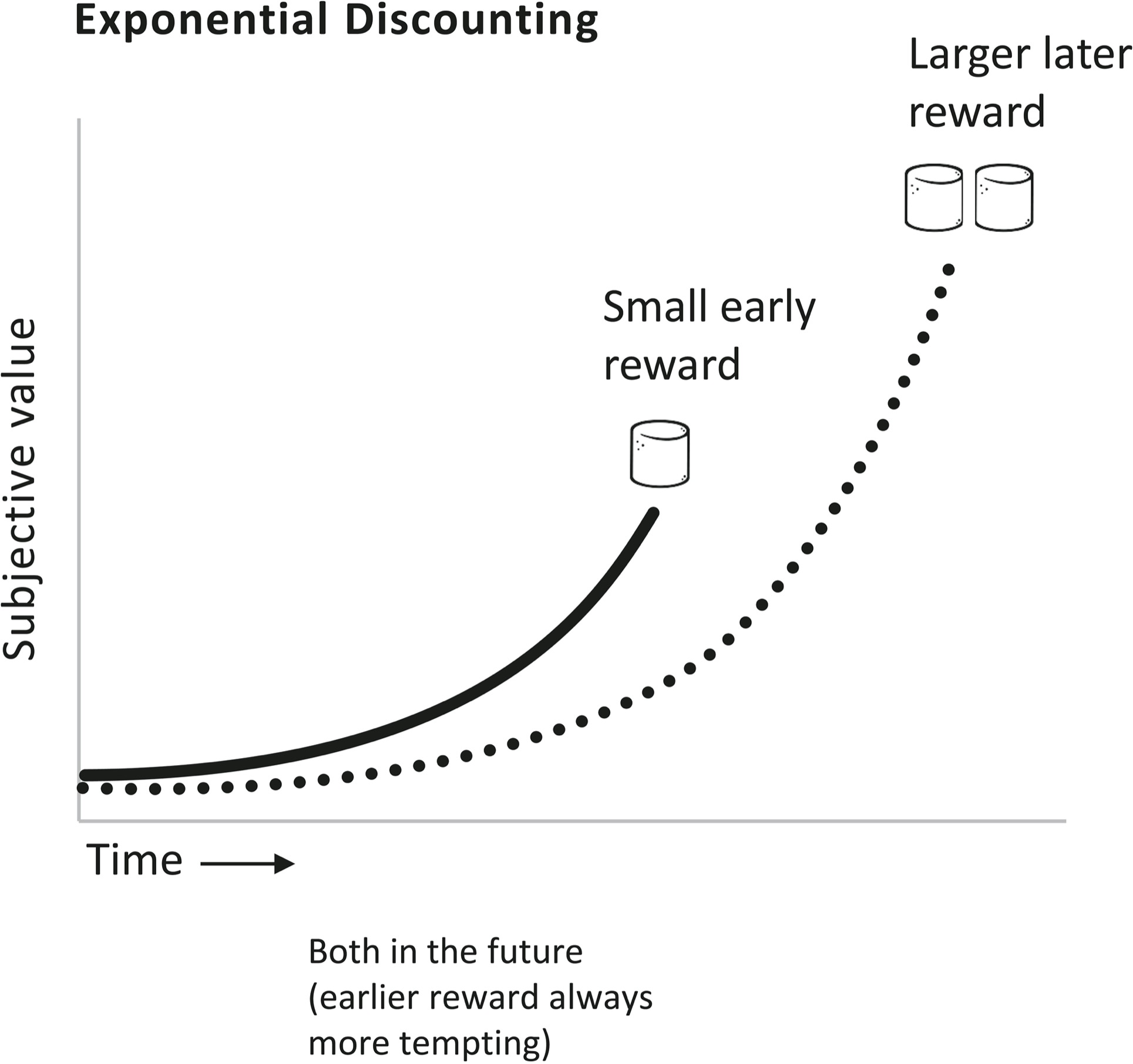

Does this mean it’s rational to eat the marshmallow now after all? Not quite—it depends on how long you have to wait and how many marshmallows you get for waiting. Let’s put aside aging and other changes and assume for simplicity’s sake that every moment is the same. Suppose that every year there’s a 1 percent chance that you’ll be struck by a bolt of lightning. That means there’s a .99 chance that you’ll be alive in a year. What are the chances that you’ll be alive in two years? For that to be true, you will have had to escape the lightning bolt for a second year, with an overall probability of .99 × .99, that is, .992 or .98 (we’ll revisit the math in chapter 4). Three years, .99 × .99 × .99, or .993 (.97); ten years, .9910 (.90); twenty years, .9920 (.82), and so on—an exponential drop. So, taking into account the possibility that you will never get to enjoy it, a marshmallow in the hand is worth nine tenths of a marshmallow in the decade-hence bush. Additional hazards—a faithless experimenter, the possibility you will lose your taste for marshmallows—change the numbers but not the logic. It’s rational to discount the future exponentially. That is why the experimenter has to promise to reward your patience with more marshmallows the longer you wait—to pay interest. And the interest compounds exponentially, compensating for the exponential decay in what the future is worth to you now.

This in turn means that there are two ways in which living for the present can be irrational. One is that we can discount a future reward too steeply—put too low a price on it given how likely we are to live to see it and how much enjoyment it will bring. The impatience can be quantified. Shane Frederick, inventor of the Cognitive Reflection Test from the previous chapter, presented his respondents with hypothetical marshmallow tests using adult rewards, and found that a majority (especially those who fell for the seductive wrong answers on the brainteasers) preferred $3,400 then and there to $3,800 a month later, the equivalent of forgoing an investment with a 280 percent annual return.17 In real life, about half of Americans nearing retirement age have saved nothing for retirement: they’ve planned their lives as if they would be dead by then (as most of our ancestors in fact were).18 As Homer Simpson said to Marge when she warned him that he would regret his conduct, “That’s a problem for future Homer. Man, I don’t envy that guy.”

The optimal rate at which to discount the future is a problem that we face not just as individuals but as societies, as we decide how much public wealth we should spend to benefit our older selves and future generations. Discount it we must. It’s not only that a current sacrifice would be in vain if an asteroid sends us the way of the dinosaurs. It’s also that our ignorance of what the future will bring, including advances in technology, grows exponentially the farther out we plan. (Who knows? Maybe we’ll teach the horse to sing.) It would have made little sense for our ancestors a century ago to have scrimped for our benefit—say, diverting money from schools and roads to a stockpile of iron lungs to prepare for a polio epidemic—given that we’re six times richer and have solved some of their problems while facing new ones they could not have dreamed of. At the same time we can curse some of their shortsighted choices whose consequences we are living with, like despoiled environments, extinct species, and car-centered urban planning.

The public choices we face today, like how high a tax we should pay on carbon to mitigate climate change, depend on the rate at which we discount the future, sometimes called the social discounting rate.19 A rate of 0.1 percent, which reflects only the chance we’ll go extinct, means that we value future generations almost as much as ourselves and calls for investing the lion’s share of our current income to boost the well-being of our descendants. A rate of 3 percent, which assumes growing knowledge and prosperity, calls for deferring most of the sacrifice to generations that can better afford it. There is no “correct” rate, since it also depends on the moral choice of how we weight the welfare of living people against unborn ones.20 But our awareness that politicians respond to election cycles rather than the long term, and our sad experience of finding ourselves unprepared for foreseeable disasters like hurricanes and pandemics, suggest that our social discounting rate is irrationally high.21 We leave problems to future Homer, and don’t envy that guy.

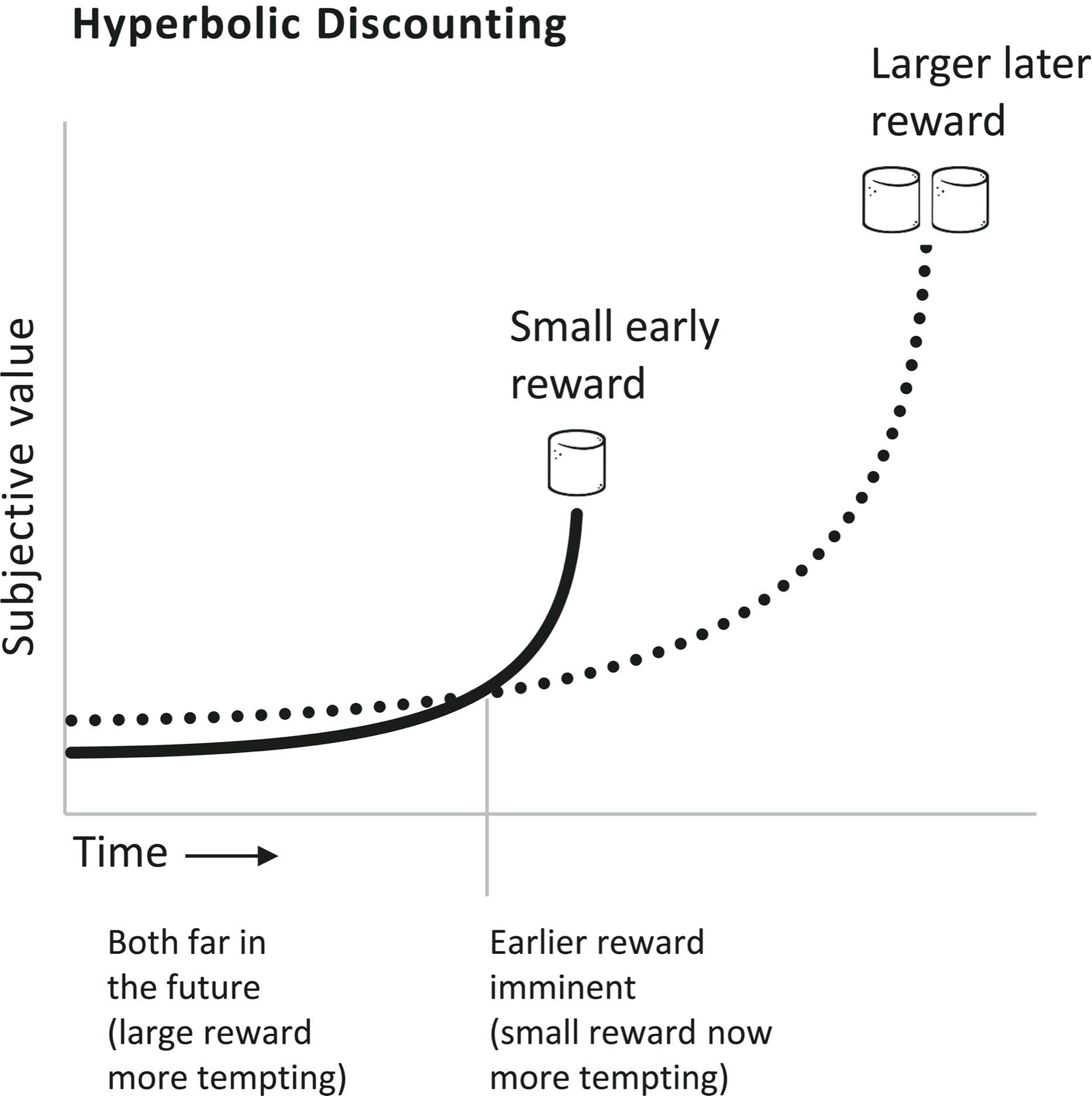

There’s a second way in which we irrationally cheat our future selves, called myopic discounting.22 Often we’re perfectly capable of delaying gratification from a future self to an even more future self. When a conference organizer sends out a menu for the keynote dinner in advance, it’s easy to tick the boxes for the steamed vegetables and fruit rather than the lasagna and cheesecake. The small pleasure of a rich dinner in 100 days versus the large pleasure of a slim body in 101 days? No contest! But if the waiter were to tempt us with the same choice then and there—the small pleasure of a rich dinner in fifteen minutes versus the large pleasure of a slim body tomorrow—we flip our preference and succumb to the lasagna.

The preference reversal is called myopic, or nearsighted, because we see an attractive temptation that is near to us in time all too clearly, while the faraway choices are emotionally blurred and (a bit contrary to the ophthalmological metaphor) we judge them more objectively. The rational process of exponential discounting, even if the discounting rate is unreasonably steep, cannot explain the flip, because if a small imminent reward is more enticing than a large later one, it will still be more enticing when both rewards are pushed into the future. (If lasagna is more enticing than steamed vegetables now, the prospect of lasagna several months from now should be more enticing than the prospect of vegetables several months from now.) Social scientists say that a preference reversal shows that the discounting is hyperbolic—not in the sense of being exaggerated, but of falling along a curve called a hyperbola, which is more L-shaped than an exponential drop: it begins with a steep plunge and then levels off. Two exponential curves at different heights never cross (more tempting now, more tempting always); two hyperbolic curves can. The graphs on the next page show the difference. (Note that they plot absolute time as it is marked on a clock or calendar, not time relative to now, so the self who is experiencing things right now is gliding along the horizontal axis, and the discounting is shown in the curves from right to left.)

Admittedly, explaining weakness of the will as a reward gets closer by hyperbolic discounting is like explaining the effect of Ambien by its dormitive power. But the elbow shape of a hyperbola suggests that it may really be a composite of two curves, one plotting the irresistible pull of a treat that you can’t get out of your head (the bakery smell, the come-hither look, the glitter in the showroom), the other plotting a cooler assessment of costs and benefits in a hypothetical future. Studies that tempt volunteers in a scanner with adult versions of marshmallow tests confirm that different brain patterns are activated by thoughts of imminent and distant goodies.23

Though hyperbolic discounting is not rational in the way that calibrated exponential discounting can be (since it does not capture the ever-compounding uncertainty of the future), it does provide an opening for the rational self to outsmart the impetuous self. The opening may be seen in the leftmost segment of the hyperbolas, the time when both rewards lie far off in the future, during which the large reward is subjectively more appealing than the small one (as rationally it should be). Our calmer selves, well aware of what will happen as the clock ticks down, can chop off the right half of the graph, never allowing the switchover to temptation to arrive. The trick was explained by Circe to Odysseus:24

First you will reach the Sirens, who bewitch

all passersby. If anyone goes near them

in ignorance, and listens to their voices,

that man will never travel to his home,

and never make his wife and children happy

to have him back with them again. The Sirens

who sit there in their meadow will seduce him

with piercing songs. Around about them lie

great heaps of men, flesh rotting from their bones,

their skin all shriveled up. Use wax to plug

your sailors’ ears as you row past, so they

are deaf to them. But if you wish to hear them,

your men must fasten you to your ship’s mast

by hand and foot, straight upright, with tight ropes.

So bound, you can enjoy the Sirens’ song.

The technique is called Odyssean self-control, and it is more effective than the strenuous exertion of willpower, which is easily overmatched in the moment by temptation.25 During the precious interlude before the Sirens’ song comes into earshot, our rational faculties preempt any possibility that our appetites will lure us to our doom by tying us to the mast with tight ropes, cutting off the option to succumb. We shop when we are sated and pass by the chips and cakes that would be irresistible when we are hungry. We instruct our employers to tithe our paycheck and set aside a portion for retirement so there’s no surplus at the end of the month to blow on a vacation.

In fact, Odyssean self-control can step up a level and cut off the option to have the option, or at least make it harder to exercise. Suppose the thought of a full paycheck is so tempting that we can’t bring ourselves to fill out the form that authorizes the monthly deduction. Before being faced with that temptation, we might allow our employers to make the choice for us (and other choices that benefit us in the long run) by enrolling us in mandatory savings by default: we would have to take steps to opt out of the plan rather than to opt in. This is the basis for the philosophy of governance whimsically called libertarian paternalism by the legal scholar Cass Sunstein and the behavioral economist Richard Thaler in their book Nudge. They argue that it is rational for us to empower governments and businesses to fasten us to the mast, albeit with loose ropes rather than tight ones. Informed by research on human judgment, experts would engineer the “choice architecture” of our environments to make it difficult for us to do tempting harmful things, like consumption, waste, and theft. Our institutions would paternalistically act as if they know what’s best for us, while leaving us the liberty to untie the ropes when we are willing to make the effort (which in fact few people exercise).

Libertarian paternalism, together with other “behavioral insights” drawn from cognitive science, has become increasingly popular among policy analysts, because it promises more effective outcomes at little cost and without impinging on democratic principles. It may be the most important practical application of research on cognitive biases and fallacies so far (though the approach has been criticized by other cognitive scientists who argue that humans are more rational than that research suggests).26

Rational Ignorance

While Odysseus had himself tied to the mast and rationally relinquished his option to act, his sailors plugged their ears with wax and rationally relinquished their option to know. At first this seems puzzling. One might think that knowledge is power, and you can never know too much. Just as it’s better to be rich than poor, because if you’re rich you can always give away your money and be poor, you might think it’s always better to know something, because you can always choose not to act on it. But in one of the paradoxes of rationality, that turns out not to be true. Sometimes it really is rational to plug your ears with wax.27 Ignorance can be bliss, and sometimes what you don’t know can’t hurt you.

An obvious example is the spoiler alert. We take pleasure in watching a plot unfold, including the suspense, climax, and denouement, and may choose not to spoil it by knowing the ending in advance. Sports fans who cannot see a match in real time and plan to watch a recorded version later will sequester themselves from all media and even from fellow fans who might leak the outcome in a subtle tell. Many parents choose not to learn the sex of their unborn child to enhance the joy of the moment of birth. In these cases we rationally choose ignorance because we know how our own involuntary positive emotions work, and we arrange events to enhance the pleasure they give us.

By the same logic, we can understand our negative emotions and starve ourselves of information that we anticipate would give us pain. Many consumers of genetic testing know they would be better off remaining ignorant of whether the man who calls himself their father is biologically related to them. Many choose not to learn whether they have inherited a dominant gene for an incurable disease that killed a parent, like the musician Arlo Guthrie, whose father, Woody, died of Huntington’s. There’s nothing they can do about it, and knowledge of an early and awful death would put a pall over the rest of their lives. For that matter most of us would plug our ears if an oracle promised to tell us the day we will die.

We also preempt knowledge that would bias our cognitive faculties. Juries are forbidden to see inadmissible evidence from hearsay, forced confessions, or warrantless searches—“the tainted fruit of the poisoned tree”—because human minds are incapable of ignoring it. Good scientists think the worst of their own objectivity and conduct their studies double blind, choosing not to know which patients got the drug and which the placebo. They submit their papers to anonymous peer review, removing any temptation to retaliate after a bad one, and, with some journals, redact their names, so the reviewers can’t indulge the temptation to repay favors or settle scores.

In these examples, rational agents choose to be ignorant to game their own less-than-rational biases. But sometimes we choose to be ignorant to prevent our rational faculties from being exploited by rational adversaries—to make sure they cannot make us an offer we can’t refuse. You can arrange not to be home when the mafia wiseguy calls with a threat or the deputy tries to serve you with a subpoena. The driver of a Brink’s truck is happy to have his ignorance proclaimed on the sticker “Driver does not know combination to safe,” because a robber cannot credibly threaten him to divulge it. A hostage is better off if he does not see the faces of his captors, because that leaves them an incentive to release him. Even misbehaving young children know they’re better off not meeting their parents’ glares.

Rational Incapacity and Rational Irrationality

Rational ignorance is an example of the mind-bending paradoxes of reason explained by the political scientist Thomas Schelling in his 1960 classic The Strategy of Conflict.28 In some circumstances it can be rational to be not just ignorant but powerless, and, most perversely of all, irrational.

In the game of Chicken, made famous in the James Dean classic Rebel Without a Cause, two teenage drivers approach each other at high speed on a narrow road and whoever swerves first loses face (he is the “chicken”).29 Since each one knows that the other does not want to die in a head-on crash, each may stay the course, knowing the other has to swerve first. Of course when both are “rational” in this way, it’s a recipe for disaster (a paradox of game theory we will return to in chapter 8). So is there a strategy that wins at Chicken? Yes—relinquish your ability to swerve by conspicuously locking the steering wheel, or by putting a brick on the gas pedal and climbing into the back seat, leaving the other guy no choice but to swerve. The player who lacks control wins. More precisely, the first player to lack control wins: if both lock their wheels simultaneously . . .

Though the game of Chicken may seem like the epitome of teenage foolishness, it’s a common dilemma in bargaining, both in the marketplace and in everyday life. Say you’re willing to pay up to $30,000 for a car and know that it cost the dealer $20,000. Any price between $20,000 and $30,000 works to both of your advantages, but of course you want it to be as close as possible to the lower end of the range and the sales rep to the upper end. You could lowball him, knowing he’s better off consummating the deal than walking away, but he could highball you, knowing the same thing. So he agrees that your offer is reasonable but needs the OK from his manager, but when he comes back he says regretfully that the manager is a hard-ass who nixed the deal. Alternatively, you agree that the price is reasonable but you need the OK from your bank, and the loan officer refuses to lend you that much. The winner is the one whose hands are tied. The same can happen in friendships and marriages in which both partners would rather do something together than stay home, but differ in what they most enjoy. The partner with the superstition or hang-up or maddeningly stubborn personality that categorically rules out the other’s choice will get his or her own.

Threats are another arena in which a lack of control can afford a paradoxical advantage. The problem with threatening to attack, strike, or punish is that the threat may be costly to carry out, rendering it a bluff that the target of the threat could call. To make it credible, the threatener must be committed to carrying it out, forfeiting the control that would give his target the leverage to threaten him right back by refusing to comply. A hijacker who wears an explosive belt that goes off with the slightest jostle, or protesters who chain themselves to the tracks in front of a train carrying fuel to a nuclear plant, cannot be scared away from their mission.

The commitment to carry out a threat can be not just physical but emotional.30 The narcissist, borderline, hothead, high-maintenance romantic partner, or “man of honor” who considers it an intolerable affront to be disrespected and lashes out regardless of the consequences is someone you don’t want to mess with.

A lack of control can blend into a lack of rationality. Suicide terrorists who believe they will be rewarded in paradise cannot be deterred by the prospect of death on earth. According to the Madman Theory in international relations, a leader who is seen as impetuous, even unhinged, can coerce an adversary into concessions.31 In 1969 Richard Nixon reportedly ordered nuclear-armed bombers to fly recklessly close to the USSR to scare them into pressuring their North Vietnamese ally to negotiate an end to the Vietnam War. Donald Trump’s bluster in 2017 about using his bigger nuclear button to rain fire and fury on North Korea could charitably be interpreted as a revival of the theory.

The problem with the madman strategy, of course, is that both sides can play it, setting up a catastrophic game of Chicken. Or the threatened side may feel it has no choice but to take out the madman by force rather than continue a fruitless negotiation. In everyday life, the saner party has an incentive to bail out of a relationship with a madman or madwoman and deal with someone more reasonable. These are reasons why we are not all madpeople all the time (though some of us get away with it some of the time).

Promises, like threats, have a credibility problem that can call for a surrender of control and of rational self-interest. How can a contractor convince a client that he will pay for any damage, or a borrower convince a lender that she will repay a loan, when they have every incentive to renege when the time comes? The solution is to post a bond that they would forfeit, or sign a note that empowers the creditor to repossess the house or car. By signing away their options, they become trustworthy partners. In our personal lives, how do we convince an object of desire that we will forsake all others till death do us part, when someone even more desirable may come along at any time? We can advertise that we are incapable of rationally choosing someone better because we never rationally chose that person in the first place—our love was involuntary, irrational, and elicited by the person’s unique, idiosyncratic, irreplaceable qualities.32 I can’t help falling in love with you. I’m crazy for you. I like the way you walk, I like the way you talk.

The paradoxical rationality of irrational emotion is endlessly thought-provoking and has inspired the plots of tragedies, Westerns, war movies, mafia flicks, spy thrillers, and the Cold War classics Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove. But nowhere was the logic of illogic more pithily stated than in the 1941 film noir The Maltese Falcon, when detective Sam Spade dares Kasper Gutman’s henchmen to kill him, knowing they need him to find the jewel-encrusted falcon. Gutman replies:

That’s an attitude, sir, that calls for the most delicate judgment on both sides, because as you know, sir, in the heat of action men are likely to forget where their best interests lie, and let their emotions carry them away.33

Taboo

Can certain thoughts be not just strategically compromising but evil to think? This is the phenomenon called taboo, from a Polynesian word for “forbidden.” The psychologist Philip Tetlock has shown that taboos are not just customs of South Sea islanders but active in all of us.34

Tetlock’s first kind of taboo, the “forbidden base rate,” arises from the fact that no two groups of people—men and women, blacks and whites, Protestants and Catholics, Hindus and Muslims, Jews and gentiles—have identical averages on any trait one cares to measure. Technically, those “base rates” could be plugged into actuarial formulas and guide predictions and policies pertaining to those groups. To say that such profiling is fraught would be an understatement. We will look at the morality of forbidden base rates in the discussion of Bayesian reasoning in chapter 5.

A second kind is the “taboo tradeoff.” Resources are finite in life, and tradeoffs unavoidable. Since not everyone values everything equally, we can increase everyone’s well-being by encouraging people to exchange something that is less valuable to them for something that is more valuable. But countering this economic fact is a psychological one: people treat some resources as sacrosanct, and are offended by the possibility that they may be traded for vulgar commodities like cash or convenience, even if everyone wins.

Organs for donation are an example.35 No one needs both their kidneys, while a hundred thousand Americans desperately need one. That need is not filled either by posthumous donors (even when the state nudges them to consent by making donation the default) or by living altruists. If healthy donors were allowed to sell their kidneys (with the government providing vouchers to recipients who couldn’t afford to pay), many people would be spared financial stress, many others would be spared disability and death, and no one would be worse off. Yet most people are not just opposed to this plan but offended by the very idea. Rather than providing arguments against it, they are insulted even to be asked. Switching the payoff from filthy lucre to wholesome vouchers (say, for education, health care, or retirement) softens the offense, but doesn’t eliminate it. People are equally incensed when asked whether there should be subsidized markets for jury duty, military service, or children put up for adoption, ideas occasionally bruited by naughty libertarian economists.36

Taboo tradeoffs confront us not just in hypothetical policies but in everyday budgetary decisions. A dollar spent on health or safety—a pedestrian overpass, a toxic waste cleanup—is a dollar not spent on education or parks or museums or pensions. Yet editorialists are unembarrassed to make nonsensical proclamations like “No amount is too much to spend on X” or “We cannot put a price on Y” when it comes to sacred commodities like the environment, children, health care, or the arts, as if they were prepared to shut down schools to pay for sewage treatment plants or vice versa. Putting a dollar value on a human life is repugnant, but it’s also unavoidable, because otherwise policymakers can spend profligate amounts on sentimental causes or pork-barrel projects that leave worse hazards untreated. When it comes to paying for safety, a human life in the United States is currently worth around $7–10 million (though planners are happy for the price to be buried in dense technical documents). When it comes to paying for health, the price is all over the map, one of the reasons that America’s health care system is so expensive and ineffective.

To show that merely thinking about taboo tradeoffs is perceived as morally corrosive, Tetlock presented experimental participants with the scenario of a hospital administrator faced with the choice of spending a million dollars to save the life of a sick child or putting it toward general hospital expenses. People condemned the administrator if he thought about it a lot rather than making a snap decision. They made the opposite judgment, esteeming thought over reflex, when the administrator grappled with a tragic rather than a taboo tradeoff: whether to spend the money to save the life of one child or the life of another.

The art of political rhetoric is to hide, euphemize, or reframe taboo tradeoffs. Finance ministers can call attention to the lives a budgetary decision will save and ignore the lives it costs. Reformers can redescribe a transaction in a way that tucks the tit for tat in the background: advocates for the women in red-light districts speak of sex workers exercising their autonomy rather than prostitutes selling their bodies; advertisers of life insurance (once taboo) describe the policy as a breadwinner protecting a family rather than one spouse betting that the other will die.37

Tetlock’s third kind of taboo is the “heretical counterfactual.” Built into rationality is the ability to ponder what would happen if some circumstance were not true. It’s what allows us to think in abstract laws rather than the concrete present, to distinguish causation from correlation (chapter 9). The reason we say the rooster does not cause the sun to rise, even though one always follows the other, is that if the rooster had not crowed, then the sun would still have risen.

Nonetheless, people often think it is immoral to let their minds wander in certain make-believe worlds. Tetlock asked people, “What if Joseph had abandoned Mary when Jesus was a child—would he have grown up as confident and charismatic?” Devout Christians refused to answer. Some devout Muslims are even touchier. When Salman Rushdie published The Satanic Verses in 1988, a novel containing a narrative that played out the life of Mohammad in a counterfactual world in which some of Allah’s words really came from Satan, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for his murder. Lest this mindset seem primitive and fanatical, try playing this game at your next dinner party: “Of course none of us would ever be unfaithful to our partners. But let’s suppose, sheerly hypothetically, that we would. Who would be your adulterous paramour?” Or try this one: “Of course none of us is the least bit racist. But let’s just say we were—which group would you be prejudiced against?” (A relative of mine was once dragged into this game and dumped her boyfriend after he replied, “Jews.”)

How could it be rational to condemn the mere thinking of thoughts—an activity that cannot, by itself, impinge on the welfare of people in the world? Tetlock notes that we judge people not just by what they do but by who they are. A person who is capable of entertaining certain hypotheticals, even if the person has treated us well so far, might stab us in the back or sell us down the river were the temptation ever to arise. Imagine someone were to ask you: For how much money would you sell your child? Or your friendship, or citizenship, or sexual favors? The correct answer is to refuse to answer—better still, to be offended by the question. As with the rational handicaps in bargains, threats, and promises, a handicap in mental freedom can be an advantage. We trust those who are constitutionally incapable of betraying us or our values, not those who have merely chosen not to do so thus far.

Morality

One more realm that is sometimes excluded from the rational is the moral. Can we ever deduce what’s right or wrong? Can we confirm it with data? It’s not obvious how you could. Many people believe that “you can’t get an ought from an is.” The conclusion is sometimes attributed to Hume, with a rationale similar to his argument that reason must be a slave to the passions. “ ’Tis not contrary to reason,” he famously wrote, “to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.”38 It’s not that Hume was a callous sociopath. Turnabout being fair play, he continued, “ ’Tis not contrary to reason for me to chuse my total ruin, to prevent the least uneasiness of an Indian or person wholly unknown to me.” Moral convictions would seem to depend on nonrational preferences, just like the other passions. This would jibe with the observation that what’s considered moral and immoral varies across cultures, like vegetarianism, blasphemy, homosexuality, premarital sex, spanking, divorce, and polygamy. It also varies across historical periods within our own culture. In olden days a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking.

Moral statements indeed must be distinguished from logical and empirical ones. Philosophers in the first half of the twentieth century took Hume’s argument seriously and struggled with what moral statements could possibly mean if they are not about logic or empirical fact. Some concluded that “X is evil” means little more than “X is against the rules” or “I dislike X” or even “X, boo!”39 Stoppard has fun with this in Jumpers when an inspector investigating a shooting is informed by the protagonist about a fellow philosopher’s view that immoral acts are “not sinful but simply anti-social.” The astonished inspector asks, “He thinks there’s nothing wrong with killing people?” George replies, “Well, put like that, of course . . . But philosophically, he doesn’t think it’s actually, inherently wrong in itself, no.”40

Like the incredulous inspector, many people are not ready to reduce morality to convention or taste. When we say “The Holocaust is bad,” do our powers of reason leave us no way to differentiate that conviction from “I don’t like the Holocaust” or “My culture disapproves of the Holocaust”? Is keeping slaves no more or less rational than wearing a turban or a yarmulke or a veil? If a child is deathly ill and we know of a drug that could save her, is administering the drug no more rational than withholding it?

Faced with this intolerable implication, some people hope to vest morality in a higher power. That’s what religion is for, they say—even many scientists, like Stephen Jay Gould.41 But Plato made short work of this argument 2,400 years ago in Euthyphro.42 Is something moral because God commands it, or does God command some things because they are moral? If the former is true, and God had no reason for his commandments, why should we take his whims seriously? If God commanded you to torture and kill a child, would that make it right? “He would never do that!” you might object. But that flicks us onto the second horn of the dilemma. If God does have good reasons for his commandments, why don’t we appeal to those reasons directly and skip the middleman? (As it happens, the God of the Old Testament did command people to slaughter children quite often.)43

In fact, it is not hard to ground morality in reason. Hume may have been technically correct when he wrote that it’s not contrary to reason to prefer global genocide to a scratch on one’s pinkie. But his grounds were very, very narrow. As he noted, it is also not contrary to reason to prefer bad things happening to oneself over good things—say, pain, sickness, poverty, and loneliness over pleasure, health, prosperity, and good company.44 O-kay. But now let’s just say—irrationally, whimsically, mulishly, for no good reason—that we prefer good things to happen to ourselves over bad things. Let’s make a second wild and crazy assumption: that we are social animals who live with other people, rather than Robinson Crusoe on a desert island, so our well-being depends on what others do, like helping us when we are in need and not harming us for no good reason.

This changes everything. As soon as we start insisting to others, “You must not hurt me, or let me starve, or let my children drown,” we cannot also maintain, “But I can hurt you, and let you starve, and let your children drown,” and hope they will take us seriously. That is because as soon as I engage you in a rational discussion, I cannot insist that only my interests count just because I’m me and you’re not, any more than I can insist that the spot I am standing on is a special place in the universe because I happen to be standing on it. The pronouns I, me, and mine have no logical heft—they flip with each turn in a conversation. And so any argument that privileges my well-being over yours or his or hers, all else being equal, is irrational.

When you combine self-interest and sociality with impartiality—the interchangeability of perspectives—you get the core of morality.45 You get the Golden Rule, or the variants that take note of George Bernard Shaw’s advice “Do not do unto others as you would have others do unto you; they may have different tastes.” This sets up Rabbi Hillel’s version, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow.” (That is the whole Torah, he said when challenged to explain it while the listener stood on one leg; the rest is commentary.) Versions of these rules have been independently discovered in Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Islam, Baháí, and other religions and moral codes.46 These include Spinoza’s observation, “Those who are governed by reason desire nothing for themselves which they do not also desire for the rest of humankind.” And Kant’s Categorical Imperative: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” And John Rawls’s theory of justice: “The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance” (about the particulars of one’s life). For that matter the principle may be seen in the most fundamental statement of morality of all, the one we use to teach the concept to small children: “How would you like it if he did that to you?”

None of these statements depends on taste, custom, or religion. And though self-interest and sociality are not, strictly speaking, rational, they’re hardly independent of rationality. How do rational agents come into existence in the first place? Unless you are talking about disembodied rational angels, they are products of evolution, with fragile, energy-hungry bodies and brains. To have remained alive long enough to enter into a rational discussion, they must have staved off injuries and starvation, goaded by pleasure and pain. Evolution, moreover, works on populations, not individuals, so a rational animal must be part of a community, with all the social ties that impel it to cooperate, protect itself, and mate. Reasoners in real life must be corporeal and communal, which means that self-interest and sociality are part of the package of rationality. And with self-interest and sociality comes the implication we call morality.

Impartiality, the main ingredient of morality, is not just a logical nicety, a matter of the interchangeability of pronouns. Practically speaking, it also makes everyone, on average, better off. Life presents many opportunities to help someone, or to refrain from hurting them, at a small cost to oneself (chapter 8). So if everyone signs on to helping and not hurting, everyone wins.47 This does not, of course, mean that people are in fact perfectly moral, just that there’s a rational argument as to why they should be.

Rationality about Rationality

Despite its lack of coolth, we should, and in many nonobvious ways do, follow reason. Merely asking why we should follow reason is confessing that we should. Pursuing our goals and desires is not the opposite of reason but ultimately the reason we have reason. We deploy reason to attain those goals, and also to prioritize them when they can’t all be realized at once. Surrendering to desires in the moment is rational for a mortal being in an uncertain world, as long as future moments are not discounted too steeply or shortsightedly. When they are, our present rational self can outsmart a future, less rational self by restricting its choices, an example of the paradoxical rationality of ignorance, powerlessness, impetuousness, and taboo. And morality does not sit apart from reason but falls out of it as soon as the members of a self-interested social species impartially deal with the conflicting and overlapping desires among themselves.

All this rationalization of the apparently irrational may raise the worry that one could twist any quirk or perversity into revealing some hidden rationale. But the impression is untrue: sometimes the irrational is just the irrational. People can be mistaken or deluded about facts. They can lose sight of which goals are most important to them and how to realize them. They can reason fallaciously, or, more commonly, in pursuit of the wrong goal, like winning an argument rather than learning the truth. They can paint themselves into a corner, saw off the branch they’re sitting on, shoot themselves in the foot, spend like a drunken sailor, play Chicken to the tragic end, stick their heads in the sand, cut off their nose to spite their face, and act as if they are the only ones in the world.

At the same time, the impression that reason always gets the last word is not unfounded. It’s in the very nature of reason that it can always step back, look at how it is being applied or misapplied, and reason about that success or shortcoming. The linguist Noam Chomsky has argued that the essence of human language is recursion: a phrase can contain an example of itself without limit.48 We can speak not only about my dog but about my mother’s friend’s husband’s aunt’s neighbor’s dog; we can remark not only that she knows something, but that he knows that she knows it, and she knows that he knows that she knows it, ad infinitum. Recursive phrase structure is not just a way to show off. We would not have evolved the ability to speak phrases embedded in phrases if we did not have the ability to think thoughts embedded in thoughts.

And that is the power of reason: it can reason about itself. When something appears mad, we can look for a method to the madness. When a future self might act irrationally, a present self can outsmart it. When a rational argument slips into fallacy or sophistry, an even more rational argument exposes it. And if you disagree—if you think there is a flaw in this argument—it’s reason that allows you to do so.