Is there a future for LTA vehicles in the United States Navy?

Since the program’s demise there has been no end of proposals to reevaluate the airship as part of the defense team—for antiship missile defense (Aegis airborne adjunct), as an antisubmarine platform, as an airborne command and control center of unequalled endurance. The attraction persists, as indicated by cyclical interest in national security circles. As long as air weighs eighty pounds per thousand cubic feet and helium eleven pounds for the same quantity, the principle of lighter-than-air aviation will remain fundamentally sound. Most of the total weight is supported courtesy of static lift—the buoyant force of the contained helium. Accordingly, LTA vehicles can move huge payloads (or very large antennas), yet are comparatively fuel efficient because a relatively small fraction of engine power is required for dynamic lift.

The 1980s sponsored a near-renaissance of the platform: the U.S. Navy assessed the surveillance airship yet again with the Patrol Airship Concept Evaluation (PACE). Generous defense budgets delivered the concept to the brink of revival.

Seeking a 600-ship Navy, the Ronald Reagan administration (1981–89) spent well over half a trillion dollars. But the emerging threat of the high-speed, low-flying cruise missile pressed the question of fleet defense, in particular the refurbished Iowa-class battleship-based groups lacking airborne radar. The Falkland Islands War (1982) and the attack on USS Stark in the Persian Gulf (1987) proved that a stealthy, comparatively inexpensive “bird” could disable high-technology warships absent high-resolution, over-the-horizon radar. Detection and engagement ability increases with altitude: air defense lifts the radar (and communications) horizon of surface ships. In response, U.S. battle groups adopted strategies against these lethal sea skimmers: surveillance HTA, the Aegis cruiser, the Phalanx machine gun. One component of a possible solution to ship defense in the age of stealth: the early warning airship. Mission: to provide over-the-horizon capability over, near, or in advance of battle groups, the farther the better.

Studies were sought late in 1984.1 The Navy and U.S. Coast Guard were working jointly—the latter service pursuing its own LTA program. During that fiscal year, the Coast Guard sought bids to lease a blimp (in 1985) for training. Projected applications: drug interdiction, military readiness, an aid to search-and-rescue. (Reliable communications are critical in at-sea emergencies.) Further, the U.S. Air Force was examining the platform’s potential for transport of maintenance personnel to remote facilities—an economic alternative to the short-range, high-maintenance helicopter.

By 1986, high-level sentiment was decidedly positive. In testimony before a House Armed Services subcommittee, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for research, engineering, and systems called the airship “a high leverage payoff” and a “simple solution which can provide cost-effective, long-endurance early-warning capability.” Evidently, LTA offered an ideal escort for naval surface forces. A request-for-proposal for an operational development model (ODM) was issued. And in June 1987, after three years of study, the Navy awarded a $168.9 million contract to Westinghouse/Airship Industries, a consortium, to develop and build one full-scale prototype at Elizabeth City, North Carolina.2 The program called for a sixty-month start-to-delivery schedule, with the ship airborne by 1990, with an existing E-2C airplane avionics suite, to evaluate operational feasibilities. The prototype would be 425 feet long and inflated with 2.5 million cubic feet of helium—the largest nonrigid yet built. Designated YEZ-2A by the Defense Department, the new ship held the hope for a naval revival. (Budget cuts forced the Coast Guard to cancel its program following tests with Goodyear’s Enterprise.) As well, it represented the first military airship slated to fly in nearly three decades:

Supporters of the ship say it will combine some of the most useful surveillance features of satellites, airplanes and surface ships, and that because it is made mostly of non-metal substances, it will be nearly invisible to enemy radar. . . . Its own radar antenna, mounted inside the gas bag, will be capable of giving timely warning of the approach not only of low-flying smugglers’ aircraft, but also of bombers, ships, and even supersonic cruise missiles hugging the waves.3

Proof-of-concept trials and sensor evaluation were to follow to convince fleet commanders that the platform was mission-capable. If successful, the service would seek bids for a fleet of surveillance airships for missile detection and for secondary missions, such as antisubmarine warfare and other requirements—a new generation of lighter-than-air craft.

The Navy’s visionary requirement was for a coherent air and sea surface picture and an extra-high level of situational awareness—essential for combat in the littorals where distances are short and time is compressed. The candidate solution, a battle surveillance airship, was selected because it could live with the force for extended periods.4

Luck is ever a factor, in any campaign. Within the Pentagon bureaucracy, termination of the ODM airship was recommended more than once; finally, it was dropped from the proposed 1989 budget. This reflected the need to save money, not the merit of the concept. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency assumed management—the Navy acting as its contractual agent. A scale demonstrator, the “Sentinel 1000,” was created by mating an enlarged envelope to an Airship Industries Skyship-600 car. As the 1990s opened, the YEZ-2A program was still afloat, but barely; limited funds realized continued delays.5 In the end, the new fiscal environment killed it—a casualty of budgetary squeeze, opposition to lavish defense expenditures, and competing factions wary of the airship’s impact on related aviation projects.6 Learning to live with less, each of the military services saw programs trimmed, sharply cut, or killed outright. With Congress determined to maintain the pressure, the naval airship—politically fraught, absent a sponsor—proved vulnerable. On the eve of promising tests with the USS Eisenhower carrier group, the hangar at Weeksville burned—destroying the demonstrator. In 1994, the Navy decided against a manned-airship program.

The military environment also had changed. The end of the Cold War in 1991 led to neglect of ASW. The absence of Soviet submarines, the primary threat to U.S. naval forces, had (it was thought) nullified the need for robust antisubmarine capabilities. The number of ASW platforms declined. Today, a new generation of quiet submarines armed with ultra-high-speed torpedoes holds major implications for control of the sea-lanes. Pentagon interest revived in 2003—a response to the growing threat of quiet, conventional, hydrogen-powered and nuclear-powered submarines, especially in the littorals.

Discarded nearly six decades ago, a naval airship may yet return as part of the national defense team—with help from modern technologies.

In 2006 the U.S. Navy acquired its first nonrigid since 1962: a small demonstration ship (MZ-3A) built by the American Blimp Corporation. The nonrigid was used in 2010 during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. “Having something at low altitude that can stay on scene a very long time is extremely valuable,” a Coast Guard admiral noted. “We are anxious to see how it works.”7 It did—as in the Second World War and in Cold War defense. Nonetheless, budgetary, political, and technical uncertainties obliged grounding following tests that included ASW sensors and after that deflation in 2015.

The dream persists; indeed, it never vanished. In 1998 about twenty-five airships were in service worldwide. This included Germany, which notably reentered the airship business. The Zeppelin NT airship built by Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH was a wholly innovative semirigid design.8

Thanks to their low fuel consumption, airships are enjoying renewed attention as an alternative in an era of high fuel prices. But while zeppelins inspire enormous loyalty among those who work on them and a sense of wonder among all who watch them soar, the financial returns have barely gotten off the ground.9

Since the prototype (1997), Zeppelin NTs have logged more than 100,000 “Flight Seeing” passengers as well as event marketing and special mission applications over Western, Northern, and Eastern Europe, Italy, South Africa, Japan, and in the United States.10

Periodically, governments, corporations, and entrepreneurs reexamine the potential of lighter-than-air: for heavy lift of outsized cargo; for resupply of remote sites of military or scientific or economic interest; for promotion campaigns; as platforms for research; as an adjunct to law enforcement in customs and illegal entry, harbor protection, drug interdiction, pollution, and fishing rights. There is also the potential as one element in national defense, that is, for military surveillance and deterrence.11 The Northrop-Grumman Long Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicle (LEMV), designed for the U.S. Army (2010–12), is the most recent project to tease success ($517 million contract) and then falter. Funding was cancelled after one flight of the RZ-4A prototype, which was then sold back to the designer. In parallel, the U.S. Air Force funded the Blue Devil II intelligence-gathering airship and then canceled it just before first flight. Intended missions: to provide persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

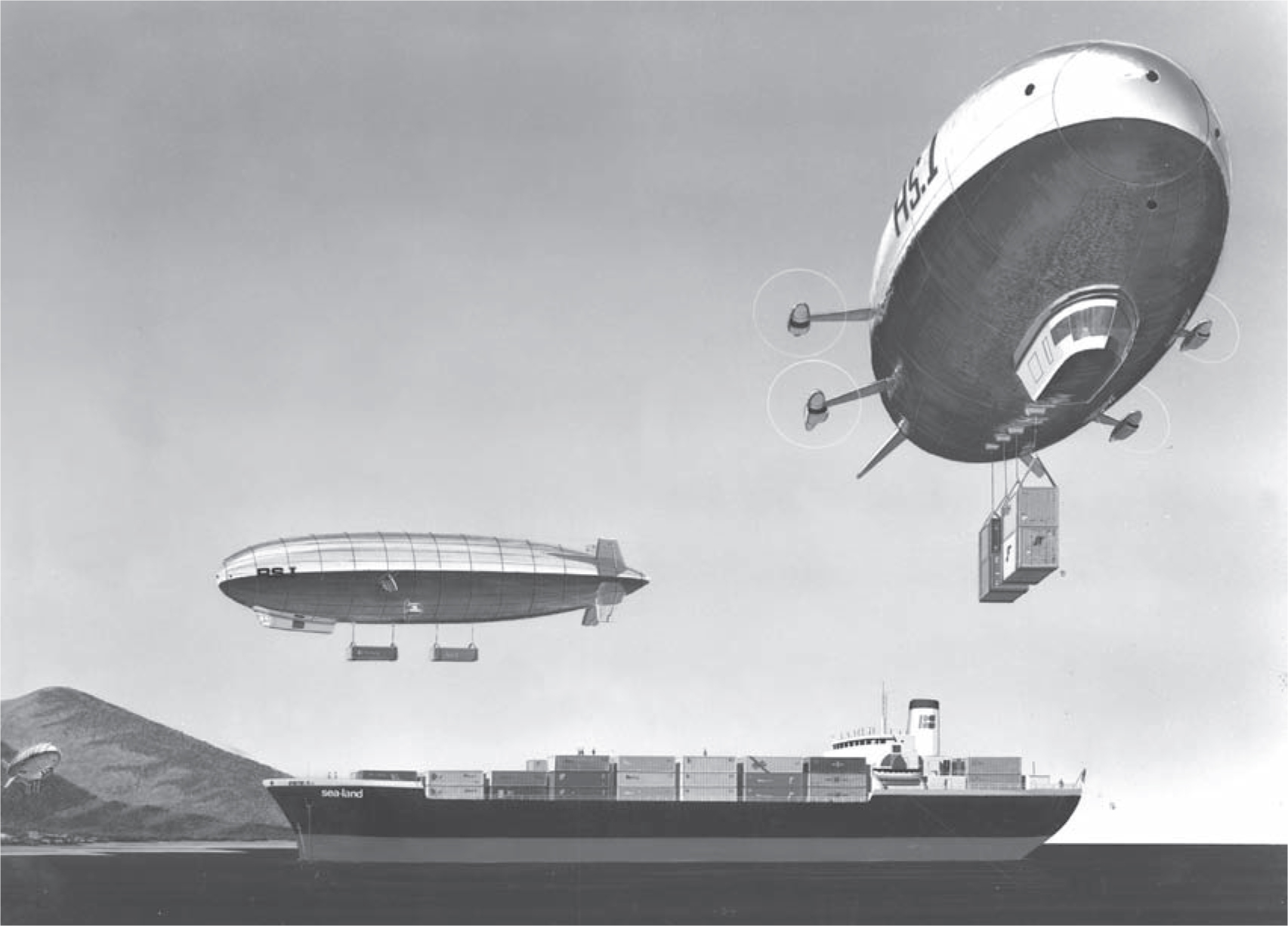

One of myriad proposals for LTA revival since disestablishment. Relatively fuel efficient and a heavy-lift platform, the modern military or commercial airship has puttered along in prototype for five decades. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Combining higher speed with heavy lift is an alluring engineering challenge. Goodyear, for one, tendered proposals both before and after disestablishment of naval LTA for transport of fully assembled missile boosters using a modified ZPG-3W (1959) and, in the 1980s, a modernized 3W as an adjunct to the fleet for AEW detection of stealthy cruise missiles. In addition, a hybrid platform, equipped with helicoptertype rotors for lift plus conventional props (for forward motion), was offered. All died on paper. A comparable hybrid—the Piasecki Heli-Stat—failed structurally during its inaugural trial in 1986 at Lakehurst.

In 2006 a further contender came forward. Lockheed Martin, the Pentagon’s largest defense contractor, publicly flew its Skunk Works P-791 prototype. Proposal: to gain agreement for a very large hybrid airship that, if practicable, could revolutionize the transport of heavy equipment used by petroleum and mining companies operating in remote terrains. In 2014 an “Aeroscraft” had been under development in California until the hangar roof collapsed.

The allure persists. Still, lighter-than-air has puttered along largely as prototype—the power of an idea. Impractical, exaggerated claims outnumber solid engineering assessments. Still, the airship’s raison d’être is extraordinary lift, range, and endurance. Comparatively economical to operate, airships have enjoyed renewed (if oft-failed) consideration in a new century fraught with the national security threats of shadowy militarylike insurgencies, rising fuel costs, strategic materials from insecure sources, and alterations to the natural systems of global climate.