The program that led to the largest—and the last—rigid airships for the Navy began in 1924. The Bureau of Aeronautics initiated preliminary design calculations for a fleet-type scout airship capable of carrying airplanes, and a partnership was arranged between the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company and Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin. Goodyear’s president, Paul W. Litchfield, a strong proponent of airships, succeeded in forming a new, jointly owned company, the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation. This transferred North American rights for the Zeppelin patents and also made key Luftschiffbau personnel available. Thus, German expertise was brought to America and saved from a seemingly bleak future in postwar Germany. The arrangement went into effect upon delivery of Los Angeles.

All of Goodyear’s experience was added to the enterprise. The thirteen German engineers who came to America were headed by Karl Arnstein, chief engineer for Luftschiffbau and vice president in charge of engineering for Goodyear-Zeppelin. The latter immediately set to work planning for commercial airships and for the large scouting ships the U.S. Navy would soon order. But the contract was not awarded for another four years.

In November 1925, BuAer recommended to the Navy Department a comprehensive program of rigid-airship development. This included a request for two ZRs and an airship base on the West Coast, in California. The matter was referred to the General Board, which held hearings and submitted a report. It made a token recommendation of one airship, “provided an appropriation can be secured for it as entirely supplementary to the appropriations for other naval needs.”1 But Admiral Moffett wanted an airship program. Early in 1926, at his instigation, a House bill was introduced to authorize construction of an airship to replace Shenandoah that insisted that funds come from the regular Navy budget. This was Moffett’s way of forcing a showdown. A tangle of congressional hearings followed.

As a result, there evolved the Five Year Aircraft Program (H.R. 9690), which included two large rigid airships—what would become the ZRS-4 and ZRS-5. The program became law on 24 June 1926. But it held only an authorization, not an appropriation. Funds were not made available until 1927. That July Arnstein’s designs were selected in the bidding process. Negotiations dragged on. A second round of competition caused further delay; Goodyear-Zeppelin again won. On 6 October 1928, the contracts for two 6,500,000-cubic-foot airships with a fixed price of $8 million were signed in Washington. Goodyear would invest in its own hangar in order to avoid interfering with operations at Lakehurst—and, it was hoped, to lay the foundation of an airship industry in the United States.

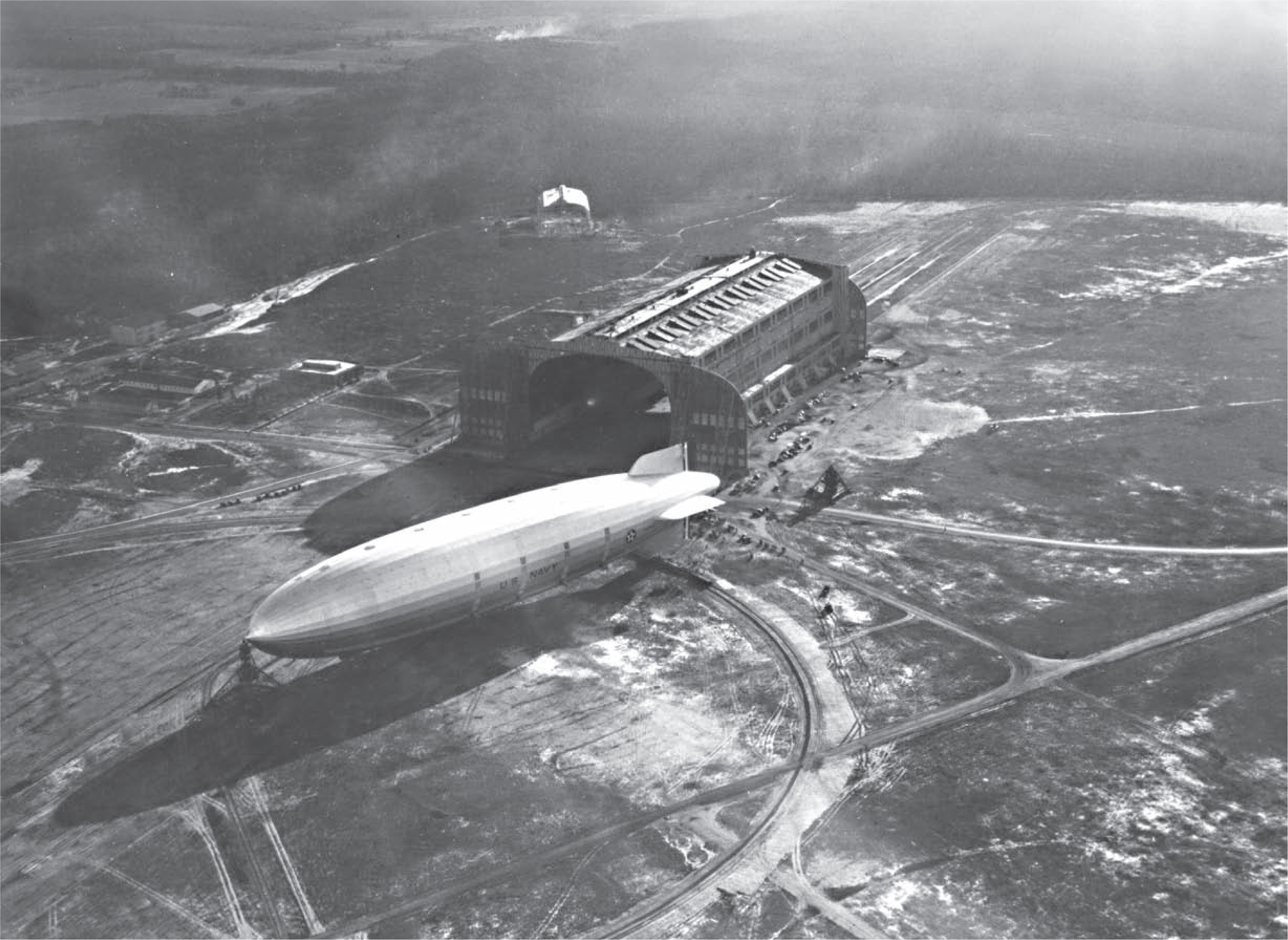

A factory and dock for the erection work was an immediate priority in Akron. Arnstein and his staff developed the basic design. The Goodyear-Zeppelin Airdock was of streamlined shape and equipped with “orange-peel” doors to minimize air turbulence—unlike those at Lakehurst. An investigation of sites for the West Coast station authorized in the Five Year Aircraft Program also began at this time. A site in the Santa Clara valley was selected; in August 1929, the Navy invited bids on construction of a hangar at Sunnyvale, California.

The dock at Akron was virtually complete on 7 November 1929 when thirty thousand persons watched Admiral Moffett officially begin construction of ZRS-4. Erection of the hull structure began in March 1930. In charge of the Navy’s small inspection force as inspector of naval aircraft (INA) in Akron was Lt. T. G. W. “Tex” Settle, USN.

Goodyear-Zeppelin Airdock, Akron, OH. The subsidiary company had invested in its own hangar—8.4 acres of floor space—to avoid interfering with operations at NAS Lakehurst and, as well, to found an industry in the United States. The Goodyear fleet of promotional blimps trained personnel for projected commercial airships. R. G. Mayer Collection courtesy Ian Ross

An immense aircraft gradually took shape. The ship’s main rings, and the intermediates spaced between them, were fabricated on the deck and raised upright into position. Then the individual corners of the rings (actually polygons) were connected by the keel girders and by longitudinal girders. The main frames for ZRS-4 and ZRS-5 were large enough to permit crewmen to climb the full circumference, if desired. This degree of accessibility was made possible through the use of inherently stiff, or “deep,” rings instead of the conventional wire-braced frames. The Navy had insisted that all parts of the structure be accessible in flight; deep rings and incorporation of three keels was Good-year’s engineering answer. The penalty was weight. But the breakup of R-38 and then Shenandoah had underscored the need for much greater hull strength and far more data relative to severe atmospheric forces, such as gust loading. This was a highly complex problem for designers; ample knowledge and understanding remained wholly incomplete in the 1920s and 1930s and, indeed, remains so today. The deep-ringed form was very rugged; the three keelways provided exceptional strength and stiffness.2

The three-keel arrangement was unique and a singular advance in design. Each was triangular in cross section and extended most of the length of the ship. One corridor ran along the top centerline, where all the valves for the gas cells were located. The other two were placed at forty-five degrees from the bottom of the hull. Here they provided access to eight engine rooms, all living quarters, galley and mess spaces, the airplane hangar, water recovery gear, the fuel, oil, and ballast tanks and lines, as well as the control cables. Access to the top catwalk was through the main rings via a series of ladders and steps. Access other than the keelways or ladders could be had by using the structure itself; transverse access by climbing the main rings; fore-aft access via the longitudinal girders in the lower part of the ship. Crewmen could now leave the corridors and walk the girders as part of their ceaseless patrols. And the design engineers were able to check their stress calculations by placing strain gauges throughout the structure—a first for any rigid airship.3

The great strength of ZRS-4 and ZRS-5 and their inflation with helium allowed the engines to be mounted inside the hull—a unique unprecedented innovation. Among the benefits was a significant reduction in drag. Four Maybach VL-2s, each delivering 560 horsepower, were installed in-line on each flank, with sixteen-foot drive shafts delivering power to sixteen-foot propellers mounted on outriggers.4 The challenge of the transmission and gearing was handled by the Allison Engineering Company, one of more than eight hundred manufacturers that supplied material or equipment for the project. The Maybach Motor Company in Friedrichshafen built and shipped the engines to Ohio, where each (dry-weight: 2,600 pounds) was bolted to its reinforced duralumin mounts. Internal engines offered safety for the on-duty mechanics, who no longer had to climb outside, and also permitted more spacious (eight-feet-square) and relatively comfortable engine rooms. The mechs on Akron and Macon found the arrangement more or less satisfactory. Finally, internal engines made possible swiveling of the propellers; each could be swung in a ninety-degree arc using a bevel gear outside and a hand wheel inside. This tilting capability, combined with the Maybach’s reversibility, gave thrust not only forward and astern but also vertically downward for heavy takeoffs or upward to help drive the ships down when landing light.

The control car, nose section, four huge fins—deep enough for the crew to enter—and tail cone were fabricated, hoisted into position, and joined to the framework. The control car was divided into three compartments. The ship’s maneuvering, gas and ballast controls, engine telegraphs, instruments, and related equipment were concentrated in the bridge area. Amidships was the chart room for the navigator and his worktable and instruments. The after space contained a ladder to the hull, the hatchway for entering and leaving the aircraft, two gun emplacements—and served as a convenient smoking room in-flight. Above the car, inside the hull, were the radio room with its Westinghouse set and rooms for the aerological officer, yeoman’s office, quarters for the commanding officer and a few fellow officers.

Living accommodations were concentrated amidships. Portside were the crew’s toilet, washroom, and a series of seven bunk rooms with four bunks each. Nonessentials were absent; only a single footlocker was provided for each man. The mess rooms for crewmen and CPOs, the officers’ wardroom, and two staterooms for officers with four bunks each were on the starboard side. Only the CO and the XO billeted alone; the others shared quarters. Two more bunk rooms were adjacent to the captain’s cabin, one with two bunks, the other with four. Living spaces were heated—an unprecedented luxury—by hot air piped in from the engine rooms.

Except for bunking, using the smoking rooms, and enjoying the sights from an auxiliary control room in the lower fin, off-watch activity focused on the wardroom and crew’s mess. The galley was equipped with a lightweight propane stove. This important appliance included a seven-gallon coffee urn, oven, two burners, and two twenty-five-quart stock pots. Designed to supply the mess needs for seventy-five men, the galleys on Akron and Macon performed admirably. Many of the off-watch section hung around the mess spaces between meal hours, reading, playing cards, or shooting the breeze.

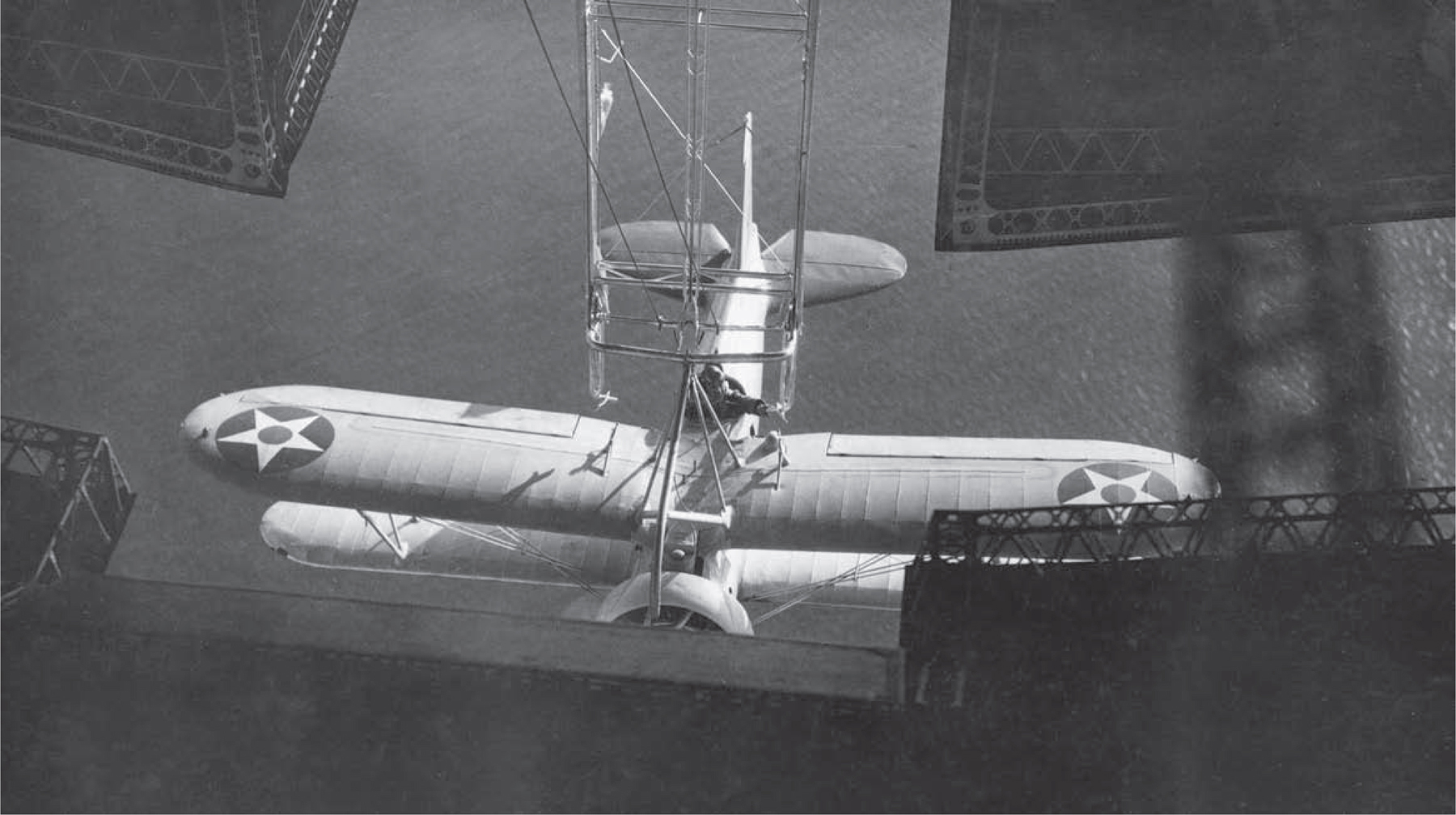

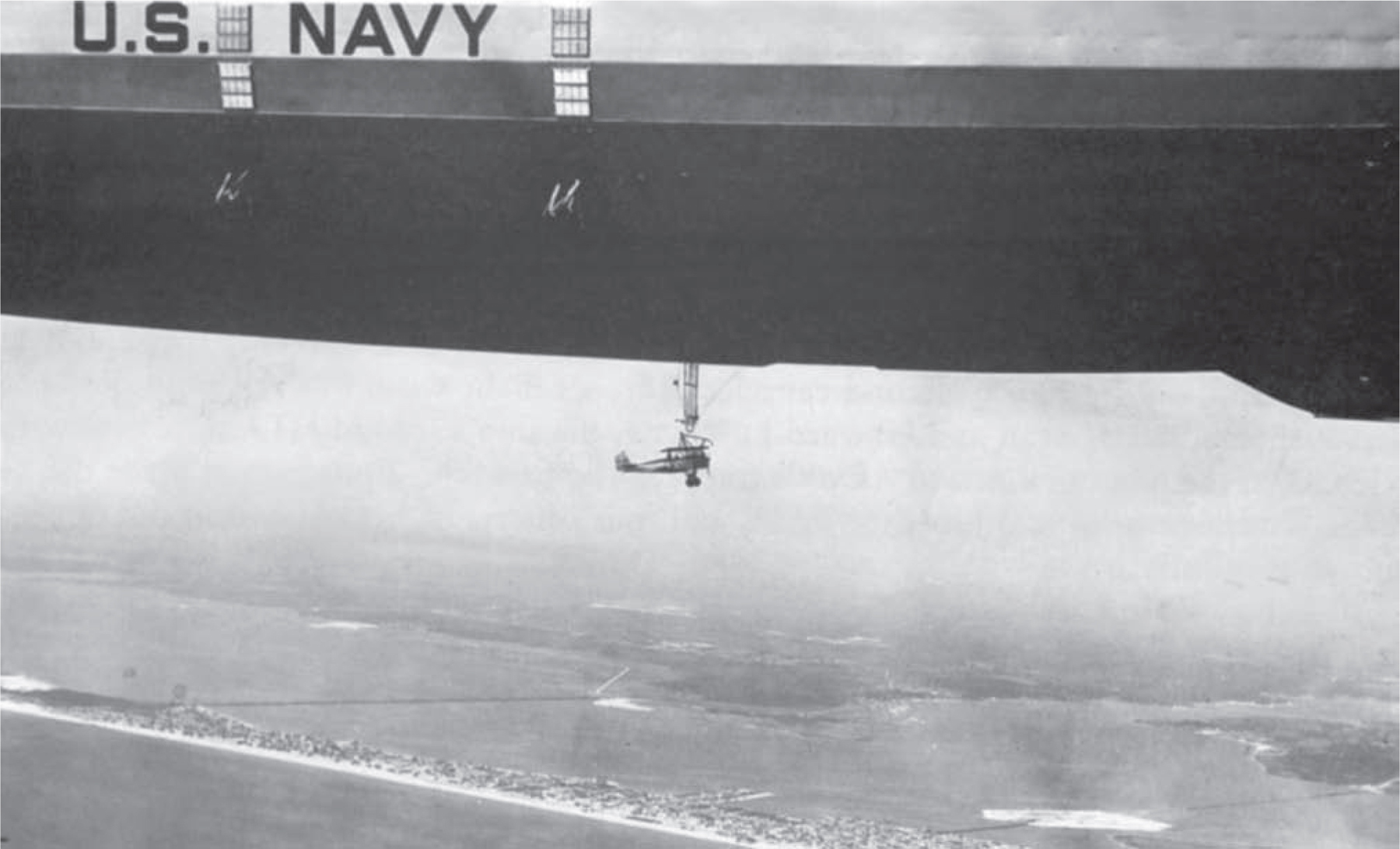

The ships’ wholly novel airplane hangar was located in the bottom of the hull just forward of amidships. The compartment, about seventy-five feet long, sixty feet wide, and sixteen feet high, was capable of stowing and servicing five planes. A trapeze, electrically operated, swung down through a T-shaped opening. The airplanes were shunted to the corners using the hangar’s X-shaped overhead trolley and monorail system; the fifth plane, if carried, remained on the trapeze.

Bunk space, USS Akron, ZRS-4. Note the portside keel corridor or catwalk: one of three running fore and aft granting access between all stations, including engine rooms nos. 1 through 8. R. G. Mayer Collection courtesy Ian Ross

The Akron’s hull was completed by the new year, and lacing on and doping of the ship’s outer cover—more than seven acres of fabric—was under way by February 1931. Work on outfitting the ship began, and the aircraft progressed toward completion.

The only significant alteration to the 1928 design was Change Order No. 2, which altered the configuration of the fins. This change was requested so the captain could see the lower fin’s auxiliary control room and visually check the trim of his ship. Unfortunately, this change invalidated the design loads calculated for the tails of ZRS-4 and ZRS-5, which as a result were too low. But this was not known until later—and by then the Navy had elected not to alter the design further.5 Goodyear-Zeppelin was obliged to defer.

With the airship nearly complete, Akron’s twelve gas cells were drawn inside through hatches, hoisted to the top of their respective bays, and painstakingly inflated. The Akron was the largest airship in the world in 1931. Despite their light weight, her twelve cells weighed more than twenty-five thousand pounds, including valves. Her largest gas cell, cell VI amidships, alone had a capacity of 970,000 cubic feet of helium—nearly 40 percent of the volume of Los Angeles.

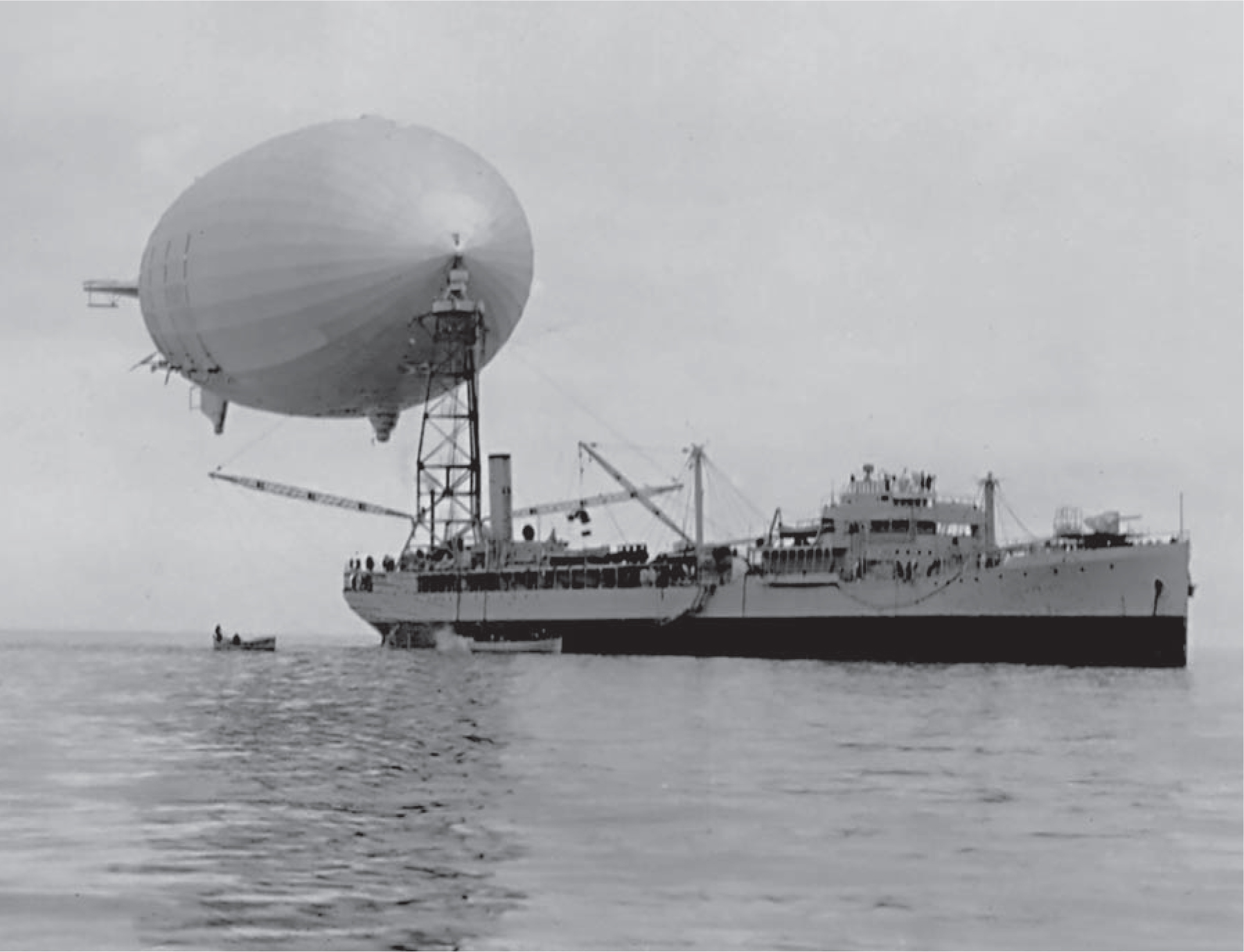

As the work proceeded in Akron, the need for search tactics for the fleet airship scout had become acute. But no airship had operated with the fleet since 1925. The State Department obtained permission from the Allied powers to use Los Angeles in military operations. As a result, she participated in Fleet Problem XII, which began on 16 February 1931 off the west coast of Panama. Los Angeles was now under the command of Lt. Cdr. Vincent A. Clarke, USN. Operating from Patoka, L.A. was exploited tactically as part of the defending White fleet. Flying the flag of the Honorable David S. Ingalls, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air, on the nineteenth Clarke succeeded in finding the main body of the “enemy” Black force, including its only carrier, Langley (CV-1). Through clever use of cloud cover, ZR-3 shadowed for several hours undetected. But the airship was found by Langley’s planes, and Los Angeles was ruled destroyed by the observer on board, Cdr. Alger H. Dresel, USN. Still, the sighting by L.A. and her two radio reports were the first reliable information as to the “enemy’s” whereabouts from any source, allowing her side to launch a highly successful attack.

Los Angeles at Guantánamo Bay, 4 February 1931. In command: Lt. Cdr. Vincent A. Clarke, USN. The ship was en route to maneuvers with the Scouting Fleet, off Panama and Costa Rica. With Akron nearing completion, search tactics for the fleet airship scout had assumed priority. Though ZR-3 was a civil ship, permission cleared her participation in Fleet Problem XII. Capt. C. W. Roland, USN (Ret.)

Los Angeles secured to Patoka, Panama Canal Zone, 7–20 February 1931. Among the units lying to anchor: USS Saratoga (CV-3) and USS Lexington (CV-2). Under Clarke, L.A. detected the main body of the “enemy” during strategic search, including its only flattop, USS Langley (CV-1). Still, disdain from fleet aviation led to scant improvement in the airship’s political prospects. In hindsight, the Navy was ceding primacy to the aircraft carrier as an offensive weapon. C. E. Rosendahl Collection/HOAC, University of Texas

The big-ship program would not be left alone to judge its own performance. In the fleet and ashore, Los Angeles’s participation in simulated war games provoked renewed controversy concerning the utility of airships. The fleet remained skeptical, and critical reports appeared in the national press, fed in part by certain factions within the Navy Department. The outstanding lesson of the 1931 fleet problem should have been that the airship itself was vulnerable and had little tactical value. The airplane-carrying airship had to exploit her planes to scout ahead while the carrier itself remained in the background, but this was not appreciated during Akron’s career and with Macon only in 1934.

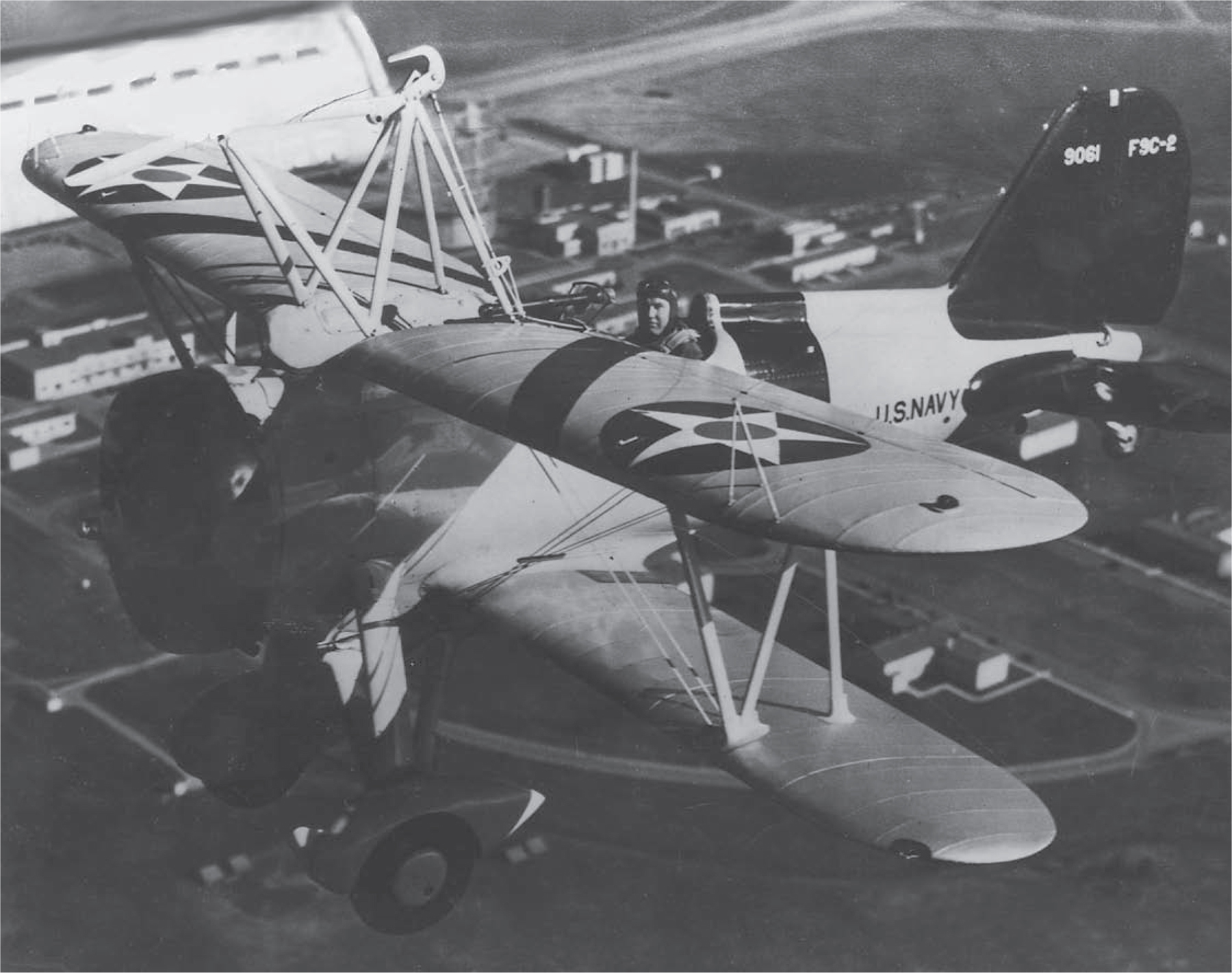

Trapeze experiments using Los Angeles were still under way, and BuAer was trying to find a hook-on plane for the Akron. A number of models were studied but the options were few. Akron’s hangar space and door dictated a small airplane, and no funds could be spared to design a special aircraft. It was finally decided to adapt the Curtiss F9C to the hook-on mission. The plane had been designed originally as a small, high-performance carrier fighter. In other words, the F9C was selected as an expedient, as were the others that operated with Akron. These were modified N2Ys and XJW-1s, used as utility planes, or “running boats,” the XF9C-1 and XF9C-2 prototypes, and the six F9C-2 squadron aircraft, procured and delivered in 1931–32. The F9C’s endurance and other characteristics as an airship plane were far from ideal, imposing restrictions on the airship-airplane scouting concept before Akron was even operational.

In September 1930 the CNO recommended to the Bureau of Navigation that hook-on training be made available to HTA pilots desiring such duty. As one result, Lt. Daniel Ward Harrigan, USN, was ordered to report to NAS Lakehurst to assist in hook-on development. He did a superb job and was instrumental in helping define the operational doctrine of the LTA carrier. And until detached in fall 1933, he was the first squadron leader of the Akron-Macon HTA units.

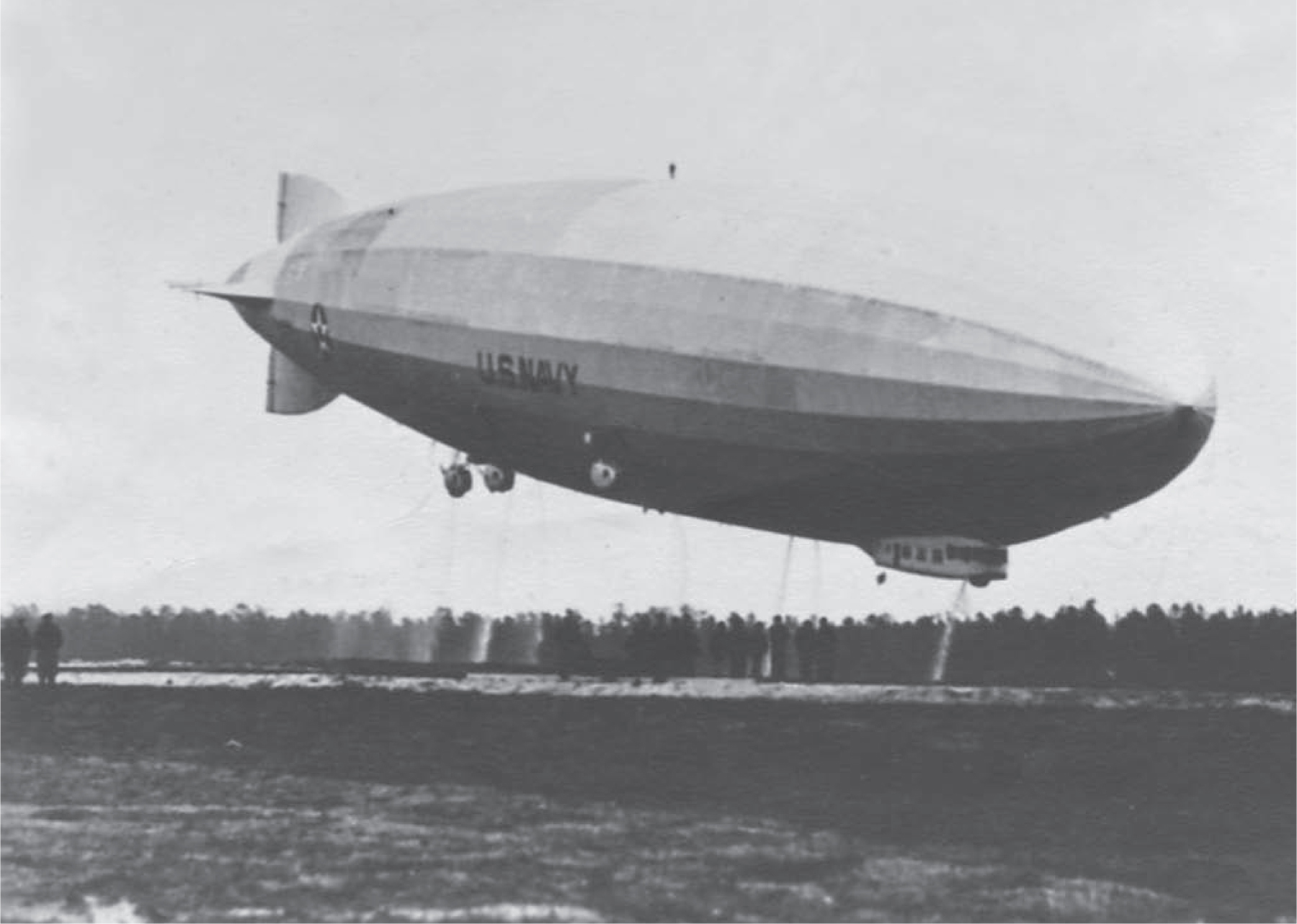

On 5 August 1931, ZRS-4 was christened before a crowd of more than a quarter of a million persons. Seven weeks later, on 23 September, with Lieutenant Commander Rosendahl in command, USS Akron was undocked for the first trial flight. The airship was weighed off on the field and, at 1537, the order “Up Ship!” was given. Akron rose statically to two hundred feet before excited spectators. Then her engines roared to life, and Akron moved off under her own power. This was the first of ten trials totaling 124 hours and 11 minutes, including a 13-hour delivery to Lakehurst, where she arrived at sunrise, 22 October. Here she was secured to the air station’s new ground-handling equipment and shunted inside next to Los Angeles. One week later (Navy Day at Lakehurst), Akron was commissioned as a vessel of the United States Navy.

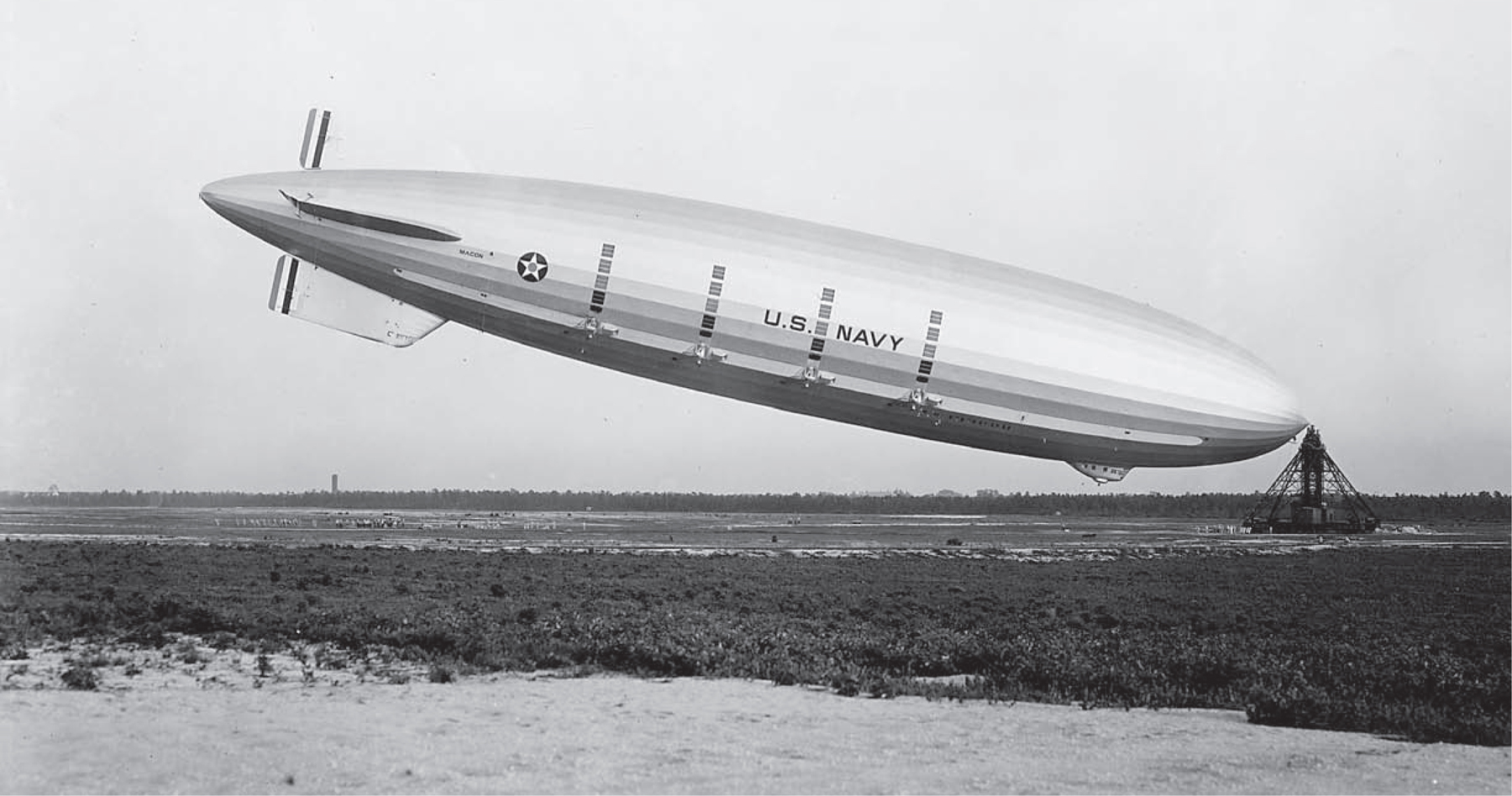

ZRS-4, USS Akron, is shunted out, 23 September 1931. The low, mobile mast was one element in the evolution in mechanical handling to provide more certain control on the deck. The ship’s commanding officer was Lt. Cdr. Charles E. Rosendahl, USN—his stature underscored by his new orders. Akron was commissioned as a vessel of the United States Navy on 27 October 1931, at Lakehurst. Goodyear

Akron is delivered, 22 October 1931. With the bow locked to a rail-mounted mooring mast, the ship’s lower fin is secured by an 85-ton stern beam riding Lakehurst’s hauling-up circle. When Akron was brought parallel to the wind, and the beam transferred to tracks leading from the hangar, the mast would shunt her into the south berth next to L.A. For takeoffs, the mast towed the assembly farther on the field to a mooring-out circle. The rail masts, beams, and circles provided control, eliminating the need for 250-man ground crews. Still, ground handling remained an unresolved operational headache. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Naval aeronautics now had a large airship, a formidable vehicle of the air, designed to join the fleet. The bitter pioneer years were astern and invaluable experience accumulated. The largest, most modern rigid airship ever designed was operational. As Akron made her inaugural flights over Ohio and from her home port in central Jersey, the airship community was alive with excitement and portent.

The interval between 1928 and 1933 was one of NAS Lakehurst’s most active and among its happiest. In anticipation of the new ships, LTA training reached a prewar high. New construction was authorized, civilian support expanded, and the number of naval personnel climbed dramatically. About twelve officers and nearly three hundred men ran the station itself. Los Angeles’s complement added twelve officers and seventy enlisted men. The Akron brought another sixteen and seventy-five, respectively, plus her pilots and airplane mechanics. And these totals did not include the large influx of student officers and enlisted trainees. NAS Lakehurst was bustling.

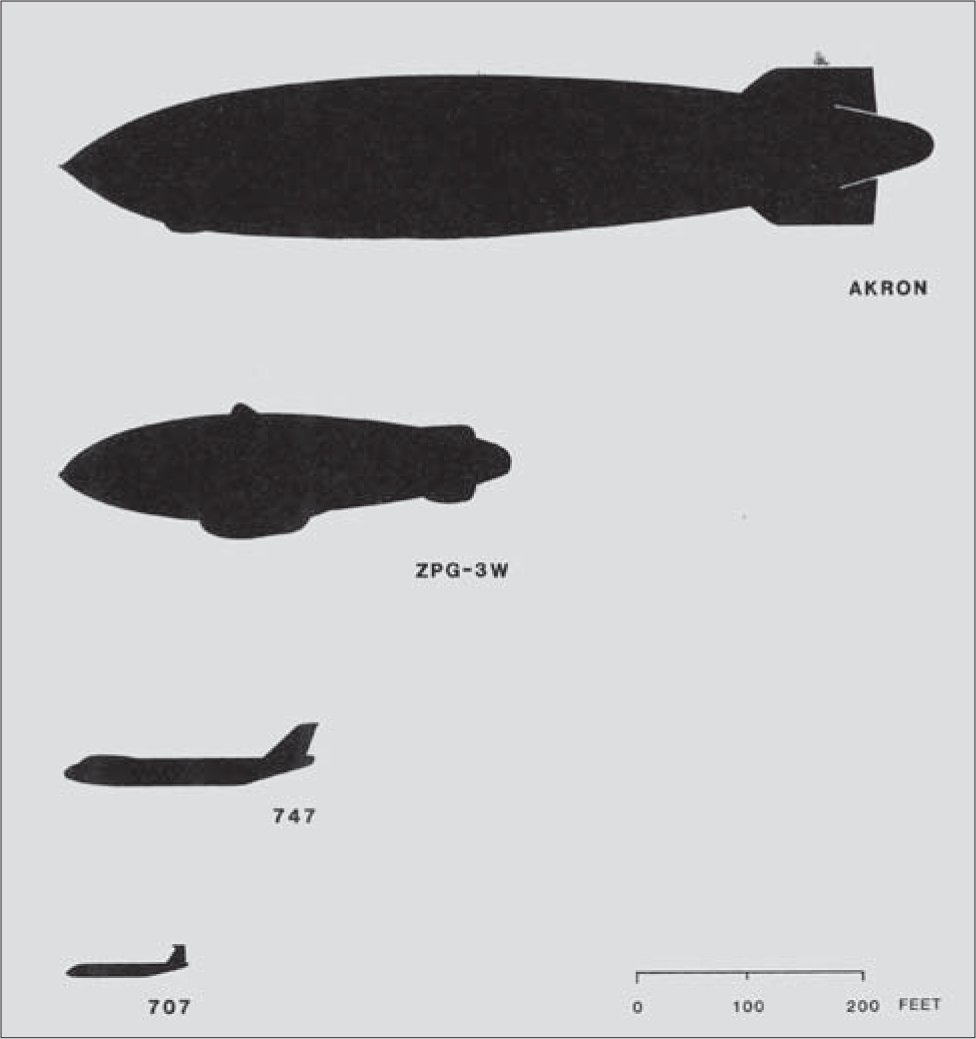

Akron compared to modern aircraft. USS Akron (1931–33) and USS Macon (1933–35) rank among the largest machines ever to navigate the air. Only Hindenburg and sister ship DLZ-130 were larger. Author

Among the most obvious changes were those for ground handling Akron. A purely mechanical system to replace that for Shenandoah and Los Angeles was essential. The problem of holding and moving the huge but relatively fragile ship in strong crosswinds dictated a system that traveled on rails. Consequently, the old docking rails and trolley slots were replaced by tracks for a rail-mounted mooring mast. A request for bids had gone out in 1930 for a mobile mast with a rectangular base riding on four railroad trucks. The work was completed within six months.

In the new system, Akron’s lower fin rested on an eighty-five-ton stern beam, or “Bolster beam,” an invention of Lt. Calvin Bolster (CC). Attached by a bridle arrangement to reinforced points on the Akron, the beam resembled a very long flatcar that traveled broadside with the ship and provided mechanical control at the stern.

The rail mast and beam undocked Akron to a “hauling up circle” immediately west of the hangar. When the mast reached its center, the beam was transferred from the hangar’s tracks to those of the circle. A small locomotive then towed the beam around until Akron was parallel to the wind. The beam was removed and the airship (usually) pulled by the mast to the center of a mooring-out circle farther out for takeoff, a taxi wheel substituting for the bumper on the lower fin. This scheme was a great advance over the old method of manhandling. It eliminated the small army formerly required on the ground, and it provided security against severe side loads in high winds.

The new system was effective but cumbersome—and it could not eliminate the human factor. On 22 February 1932, Akron broke loose from the beam. Freed at the stern, the 785-foot ship vaned about her nose-hold as the lower fin banged its way around the field until Akron pivoted and came to rest parallel to the wind. The fin was heavily damaged, and ZRS-4 did not fly again for two months.

On 2 November 1931, Akron made her first flight as a commissioned vessel. Admiral Moffett and a party of aviation journalists and NBC men embarked as passengers for a flight down the Jersey coast to Washington. On the return leg, Los Angeles and Akron flew in formation to New York City—the Navy’s sole two-ship operation with the rigid type. Earlier, too little helium had been available for both ZR-1 and ZR-3; now Akron would be lost less than three weeks before her sister ship’s maiden flight; and Los Angeles would be decommissioned at the end of fiscal year 1931.

The next day, Akron made a short flight with 207 persons on board—a world record for a single aircraft. One of her officers recalled that “the passengers sat on the catwalks, hung on the girders and were stacked in the bunk rooms. Luncheon was cold roast beef sandwiches and coffee for all.”6 The motive, again, was public relations. The flight was made to demonstrate that in an emergency, large airships could provide a high-speed airlift of troops.

Lakehurst, 22 February 1932. Broken free from the stern beam and held to the mast, Akron encountered a brisk northwest wind—her lower fin banging around until the ship was parallel with the wind. A flight to the West Coast to join the fleet had to be cancelled, and Akron did not fly again for two months. “Zero hours” required all personnel involved with flight ops to be at the hangar ready for duty. Typically, these were early for best wind conditions. Akron’s departure for Panama on 11 March 1933 would realize several close calls, exasperating the then-skipper, Cdr. Frank C. McCord: “After standing by nearly all night we finally got out of the hangar [into an 18-to-25-knot cross-hangar wind] about 0230 and away from the vicinity at 0400. It was bitter cold.” U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

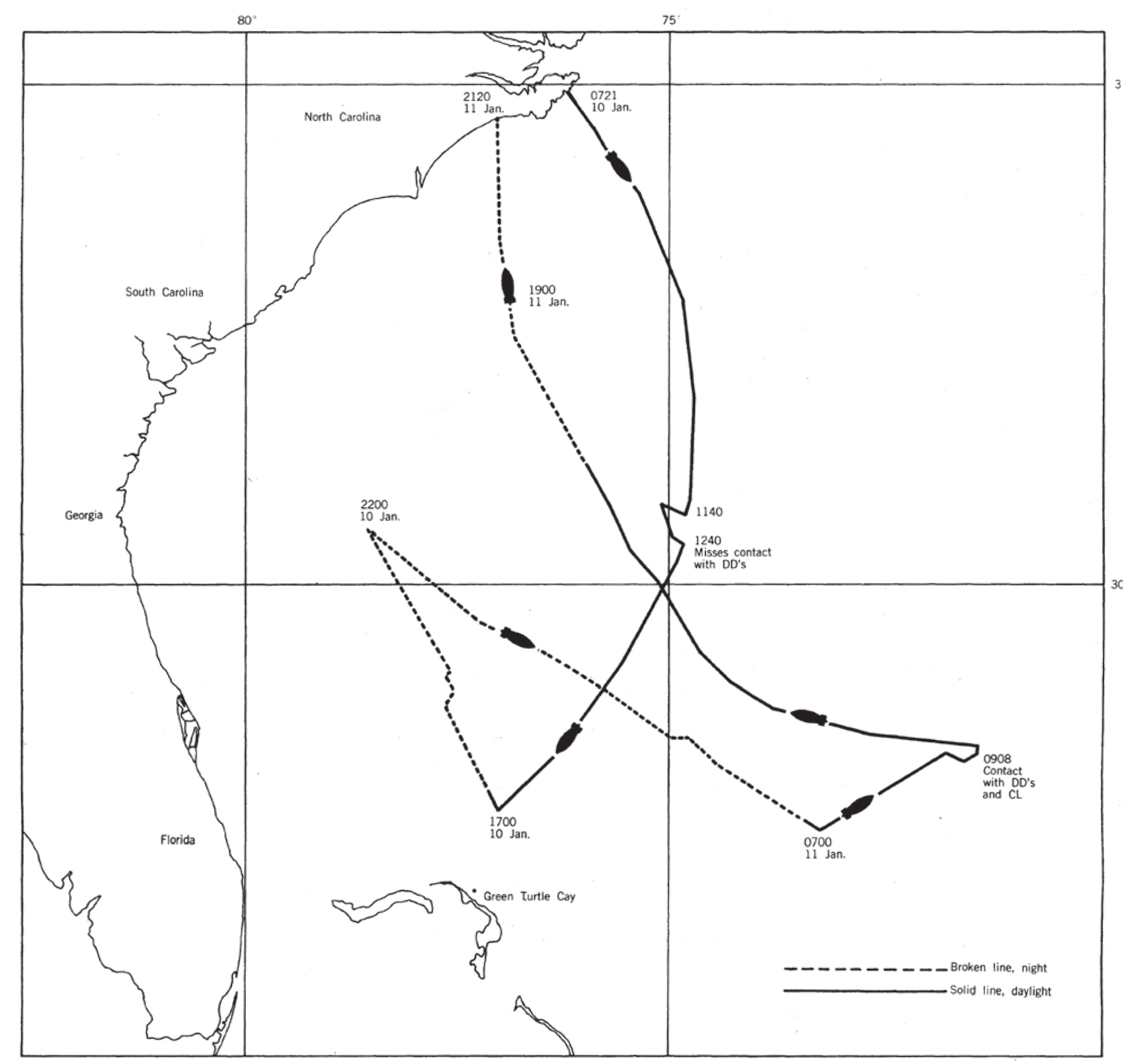

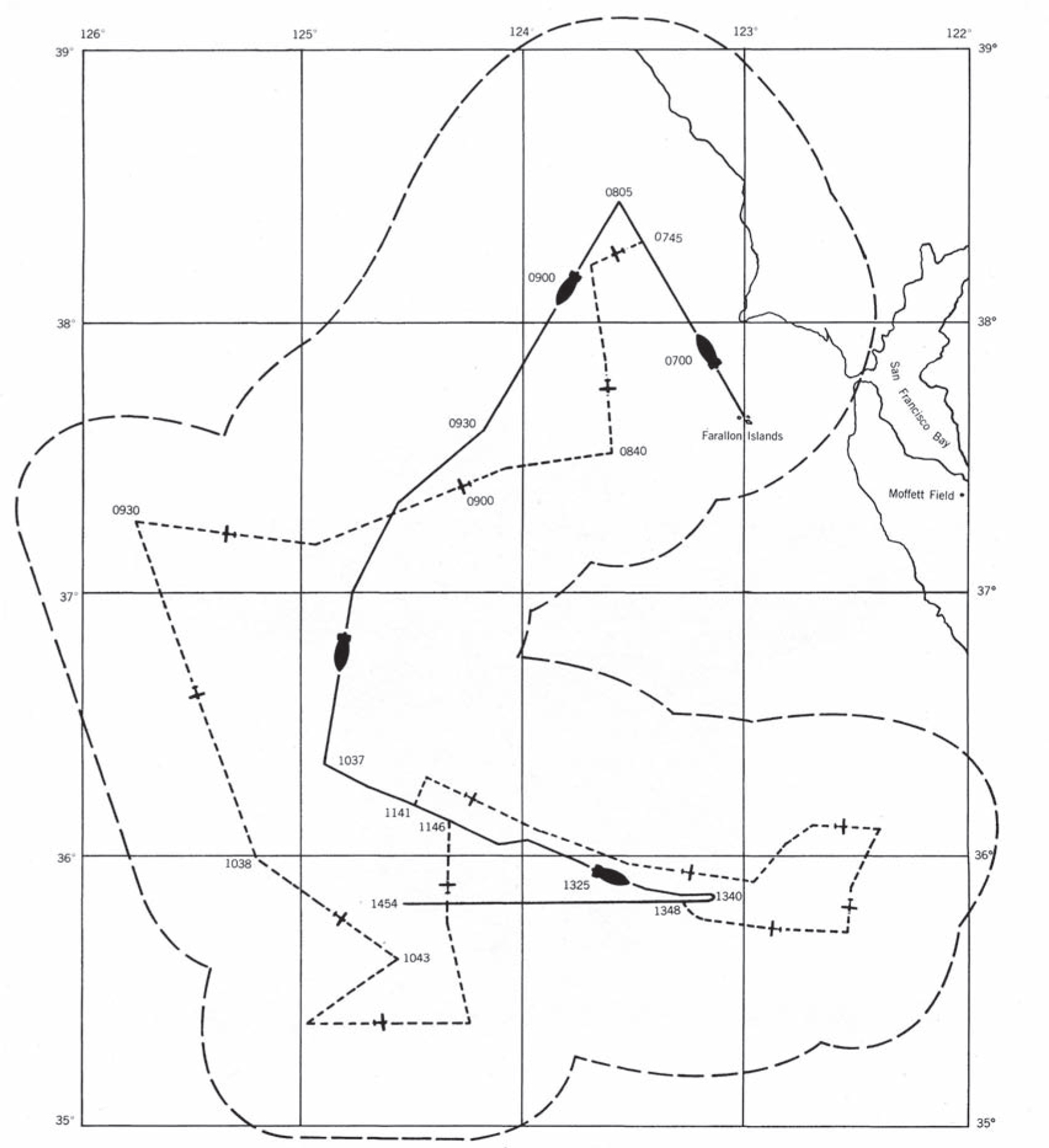

Akron’s most important hours were those with the fleet. In January 1932, the new ship conducted her first strategic exercise. The Akron had orders to be off Cape Lookout, North Carolina, at daylight on the tenth and begin a search for a squadron of destroyers from the Scouting Force. She was to find and shadow this “enemy” force and keep the commander of the Scouting Force informed by radio of its position, course, speed, and disposition. Akron departed Lakehurst in miserable weather on the ninth; the next morning, battle lookouts posted, she steered out to sea. Her trapeze had yet to be installed, so Akron carried no planes and conducted her search like a Great War Zeppelin. Her sailors stationed as lookouts did not sight the destroyers—and the “enemy” was present. Akron in fact passed within fifteen miles of the surface units. Resuming her search at daylight on the eleventh, Akron found the destroyer force two hours later, and, soon after, she was released from the exercise.7

Akron should have discovered the enemy the first day. Her hook-on planes would have extended her range of reconnaissance, and the enemy would not have gone unseen and unreported. Airship proponents had been promising a stunning performance since 1925. Thus, Akron’s first operation with the Scouting Fleet was only a qualified success and, in certain quarters, viewed as something of a disappointment given sixty-two hours in the air and the vast area of ocean covered. In 1932 no military airplane in the world was capable of such a performance. Akron had yet to prove herself or and the notion of a ZRS scout for the fleet.

Track of USS Akron operating with the Scouting Fleet, 9–12 January 1932. With the trapeze not yet installed, no planes were aboard. Akron was in the air sixty-two hours; in 1932, no military airplane in the world was capable of such a performance. ZRS-4 would work with the fleet only twice before foundering. Adapted from Smith, 1965

Cast off from her mobile base, ZRS-4 is steaming for Lakehurst and the “barn.”

Akron moored to Patoka off Hampton Roads, 17 January 1933, following her exercise with the Scouting Fleet. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Completion of Akron’s hook-on gear and receipt of her airplanes was very slow. No planes had been aboard in January; now, with Akron again due to join the fleet on the West Coast, her trapeze was rush ordered from the Naval Aircraft Factory, delivered to Lakehurst in February, and installed only days before her scheduled departure. But the tail smashing had canceled Akron’s flight west. It was not until 3 May that Lieutenants Harrigan and Howard L. Young, USN, flew the XF9C-1 to the first hook-ons. The first F9C-2 production plane did not reach Lakehurst until late June; four additional officers for her HTA unit did not join Akron until July.

Hook-on operations with Los Angeles had long since been routine; hence, scant difficulty was encountered with Akron as a carrier, especially after the skyhook was redesigned by Bolster to give the pilot maximum vertical tolerance during approach. Indeed, it was the consensus among the hook-on pilots that a trapeze “landing”—both aircraft navigating the same medium—was unusually simple compared to a conventional landing, let alone one on a flight deck.

Harrigan and fellow officers of the HTA unit were soon convinced that the hook-on planes’ primary mission was scouting. The airship itself was a carrier that supported her planes and acted as the service and communications center for them. Contact with the enemy by the carrier was deemed highly undesirable. This view was not popular with most of the airshipmen. In 1932, with Akron operational, the airship’s proponents and publicists still emphasized the protective and defensive role of the hook-on capability, and the threat of airplane attack on the airship had yet to be appreciated. In sum, Akron was not to be a lighter-than-air carrier but, instead, a scouting airship that happened to carry airplanes.

Flying the XF9C-1. Lt. Howard L. Young closes his approach and hooks onto Akron’s trapeze with his skyhook, 3 May 1931. When locked onto the trapeze’s yoke, Young idled his engine as the plane was swung up and into Akron’s hangar compartment. This was the first day that planes were operated on Akron’s trapeze. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

A Consolidated N2Y-1 running boat on approach to Akron. Introduced to the trapeze, hook-on pilots found it easier to “land” there than on a hard runway, much less a carrier flight deck. Search tactics exploiting Akron’s hook-on F9Cs, to extend the airship’s scouting line, had yet to be drilled into doctrine. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Akron’s HTA unit, June–July 1932. From left to right, Lt. (jg) Robert W. Larson, Lt. (jg) Harold B. Miller, Lt. Frederick M. Trapnell, Lt. Howard L. Young, and Lt. (jg) Frederick N. Kivette. Not pictured, Lt. D. Ward Harrigan, senior naval aviator. R. G. Mayer Collection courtesy Ian Ross

Squadron insignia for the HTA units assigned to Akron and Macon, the “men on the flying trapeze.” Capt. G. Fulton, USN (Ret.)

Akron (ZRS-4) and sister ship Macon (ZRS-5) were the only aircraft of any type originally designed for an airplane-carrying mission. Operationally, both were fleet-type strategic scouts, prototypes for a projected squadron of very long-range LTA carriers that were never authorized. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Magazine, May 1932

The Navy Department was determined to send Akron west. Rigid airships were low-altitude aircraft intended for reconnaissance over water, not continental land masses with their turbulent air masses and thermals. ZRS-4 was particularly ill-suited for transiting ten-thousand-foot mountain terrain. Nevertheless, Akron and her sister ship would be ordered to cross the continental United States five times, although a safer but longer route was available. Thus, on 8 May 1932, the airship departed Lakehurst for California. Stowed aboard were the XF9C-1 and the N2Y—hardly the best aircraft for fleet exercises. Eighty-eight hours later, on 11 May, Akron arrived at Camp Kearney, an auxiliary base near San Diego to refuel. The still-incomplete naval air station at Sunnyvale was logged on the thirteenth.

Most of Akron’s sorties along the West Coast consisted of exhibition or handwaving flights to satisfy insistent public demands to see her. And a much-hurrahed moor to Patoka in San Francisco Bay was logged. Akron’s crew was accumulating much-needed experience with their ship, but vital work with the units of the fleet was little served by these excursions.

During 1–4 June, Akron took part in tactical exercises with the Scouting Force, her planes not aboard. On 2 June, less than twenty-two hours out of Sunnyvale, Akron found the fleet and took up station in its wake. But the cruisers below had planned a reception, using their seaplanes to “attack” the airship as she held to her contact. In one instance Akron was attacked within an hour of her sighting the enemy; within a half hour in another. Rosendahl deemed it perfectly apparent that his hook-on planes could have repelled his attackers with his own armament and, if carried, could have expanded the airship’s scouting line. Akron landed after 75.5 hours in the air.

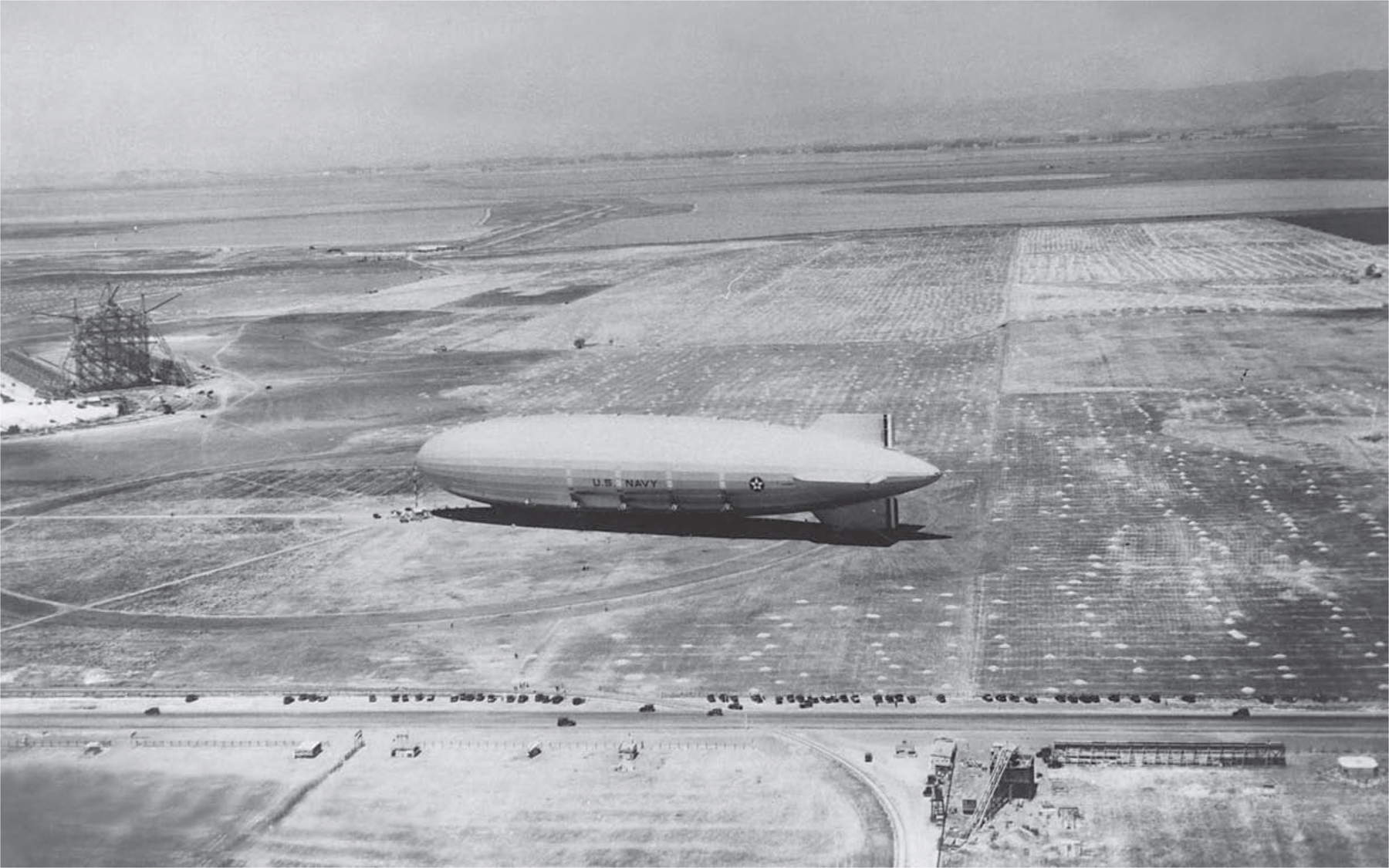

Akron at Sunnyvale, CA, June 1932. Exploiting a stick mast, ZRS-4 conducts her second exercise with the Scouting Fleet. Away from homeport for five weeks, the ship’s crew was logging valuable experience in what was still a new ship. No one could know that Akron had participated in her last fleet exercise or that the ZR had logged its last strategic search with the fleet. Note hangar construction. Cost for the West Coast naval air station: nearly $5,000,000. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

Commander in chief, U.S. Fleet, in his report to the CNO, found little positive to note. Adm. Frank H. Schofield, USN, was a bitter critic of the airship. He reiterated his view “which I have long held” that the rigid airship was entirely unsuitable for naval service in terms of cost, of excessive dependence on kindly weather and hangar facilities, and its “extreme vulnerability” to airplanes. He conceded a possible use in locating commerce raiders during daylight—prescient in light of the havoc caused by German surface raiders during the Second World War. The admiral concluded his report with the recommendations that no more rigid airships be built, that the contract for Macon be canceled, Patoka be returned to general service, and that Akron operate as part of the fleet under the command of an officer afloat.8

Akron departed for the East Coast and reached Lakehurst on the evening of the fifteenth. She had been away from her home base for five weeks—“a fact appreciated only by the airship men.”9 This was Rosendahl’s last flight as commanding officer of Akron, and his last in command of any Navy airship. Cdr. Alger H. Dresel relieved Rosendahl on 22 June. Cdr. Frank C. McCord reported to the Akron for duty under instruction as her prospective commanding officer. Although no one could have known, Akron had participated in her last exercise with the fleet, and the rigid airship had enjoyed its last strategic search with the fleet.

Naval aviator (airship) no. 3174, Lt. Cdr. Charles E. Rosendahl, USN, disembarking from the after-end of Akron’s control car. Holding a near-theocratic belief in airships, “Rosie” exercised resolute-to-ruthless control, his tireless advocacy and influence earning enemies. A steely, exacting officer, he wrote reports as Akron’s commanding officer (1931–32) that suggest that drilling to integrate the hook-on concept into scouting doctrine had yet to commence. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

The spring of 1932 was a turning point in the careers of both Los Angeles and Akron. From a pinnacle of prosperity in 1929, the United States had descended into the depths of depression. The national mood demanded frugality from all sectors, including the armed forces. By early 1932 Congress had little inclination to fund three operational rigid airships. In view of Washington’s firm attitude, the Navy Department decided as a matter of policy to operate only two ZRs simultaneously, and, on 9 May, the BuAer recommended to the Secretary of the Navy (SecNav) that Los Angeles be decommissioned on 30 June. Two days later, the airship’s commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. Fred T. Berry, USN, was warned of the prospective decommissioning.

On 13 May 1932, the CNO ordered Lakehurst to decommission Los Angeles no later than 30 June. The ship was to be docked and preserved such that she could be recommissioned “at some future date.” This was the first—and destined to be the only—time that a Navy rigid airship was placed out of commission, so BuAer emphasized a careful program of preservation. Berry was advised to assume an indefinite period of deactivation but certainly not less than one year. Recommissioning was to be made practicable on thirty days’ notice and demand a minimum of funds and effort. In the meantime, a nucleus crew of fifteen men was authorized for Lakehurst for inspection and upkeep.10

Los Angeles streams emergency ballast during heavy landing. In May 1932 the CNO ordered Lakehurst to decommission ZR-3 no later than 30 June to save funds. Returning inland, landing stations were piped at 0430 24 June; at 0448, trail ropes and the main cable were dropped. Docking was immediate. At 0552 L.A. was moored. Service totals: 4,126 hours and 36 minutes (336 flights). Formal decommissioning: 30 June—consigning ZR-3 to air station custody. Note the figure inspecting maneuvering valves. ADC J. A. Iannaccone, USN (Ret.)

On 30 June 1932, the ship’s officers and crew mustered in formation along with that of Akron, Berry read his orders, the commission pennant and colors were hauled down, and Los Angeles formally decommissioned. The painstaking work of laying up the aircraft proceeded. The hull was carefully docked on shores and cradles in a new docking position on the north side of Hangar No. 1, and cable suspensions to the overhead attached topside and tensioned. The fourteen gas cells were partially deflated (later, they were removed), all the engines were unshipped for storage, and the power cars closed off with tarpaulins. All the ship’s instruments, equipment, storage batteries, generators, papers, and other items were removed. Ballast bags and fuel tanks were removed, cleaned, then reinstalled. The fuel and water lines were drained and the airship’s essentials cleaned, lubricated, greased, lashed down, sealed, or removed and stored as required. The airship would remain docked and immobile for the next eighteen months.

Akron was formally detached from fleet duty as of 1 July and assigned to the Rigid Airship Training and Experimental Squadron. Akron thus replaced Los Angeles in training the Macon detail organized soon after the decommissioning. Each section of the Macon crew flew with the Akron crew. The two ships were similar, so the men slated for the new ship became fully familiar with Macon well before her trials. Akron also was used for airship development and experimental work. Many extended flights to sea were made to drill her lookouts. Hooking on was intensively practiced. A new method of navigating her planes beyond the horizon was tested and, most important, the first steps taken toward improving radio communications and homing gear for use between the carrier and her aircraft.

On 3 January 1933, Cdr. Frank C. McCord, USN, read his orders as commanding officer, USS Akron. McCord wasted no time. Less than five hours after the change of command ceremony, Akron was weighed off, undocked, and en route to Florida and the expeditionary mast at the Naval Aviation Reserve Base at Opa-Locka, near Miami. The airship then jumped off for Cuba. The purpose of this, and a second flight to Panama that March, was to explore possible mooring sites for operations away from the northeastern winter. On the flight to Cuba ZRS-4 did not land but, instead, circled while ferrying inspecting officers down to Guantánamo Bay with her airplanes.

McCord was delighted with his results. Akron was away from home port for ten days, including six days spent at Opa-Locka exploiting perfect flying weather for local training flights. The Opa-Locka base was slated as a winter operating base for Akron. The layover gave the ship’s crew and ground personnel practical experience for future operations.

In the evening of 3 April 1933, Akron departed Lakehurst on a routine training mission. It was the airship’s seventy-fourth flight. In addition to the ship’s regular flight crew of ten officers and fifty enlisted men, Admiral Moffett and his aide Cdr. Fred Berry, Lakehurst’s executive officer, and one guest also were on board. The Akron and nearly all aboard were never seen again.

Lakehurst’s aerologist and Akron’s aerological officer saw no unusual threat in their data that morning. McCord and Lieutenant Commander Wiley, Akron’s executive officer, conferred with the latter officer, and the decision was made for flight. Akron cast off the mast at 1928. Within hours, however, Akron was flying ahead of an extremely intense cold front, which soon enveloped her. McCord headed Akron east to ride out the storm at sea. Minutes after midnight, the air became very turbulent, and Akron was carried downward. Full speed on all eight engines and emergency ballast forward stopped the descent at seven hundred feet, and Akron returned rapidly to her cruising altitude at sixteen hundred feet. Two to three minutes later the air became exceedingly turbulent, and Akron was caught in a descending current. Wiley realized that the ship must be near the storm center. She fell rapidly, inclined by the stern by as much as twenty-five degrees. The first lieutenant sang out, “Eight hundred feet!” The ship lurched sharply, and the rudder man reported no response from his wheel. Wiley had time to unclutch the lower rudder before the cable to the upper rudder also carried away. The ship’s angle climbed to forty-five degrees, and the men had to hang on to remain on their feet. Wiley braced himself for impact with the water.

[But] the Akron was already in the sea. The unusually violent “gust” which shook the airship so severely and carried away the lower rudder’s controls was not a gust. It was the impact of the Akron’s lower fin striking the sea. And the strange gusty and bumpy air which Wiley felt was the action of the sea pouring into the fin and lashing at the airship’s after-hull areas, dragging her stern into the ocean. The Akron’s eight engines labored to make her airborne again, but they could not prevail against the submerged fin’s sea-anchor effect; they could only drag her floundering through the water and pull her nose up in a grotesque attitude-where the Akron stalled and surrendered to the sea.11

Someone called out, “Three hundred feet!” Wiley sighted the waves and shouted, “Stand by for a crash!” When the control car hit the sea, Wiley was swept out a window. When he came to the surface, he started to swim toward the foundering airship. Most crewmen could not escape the sinking wreckage; of those who did, most succumbed to the frigid water. The German motorship Phoebus, nearby, noticed lights falling toward the water and raced to the scene. Wiley was hauled aboard, and three more men found clinging to a fuel tank, including the chief radioman, who died on board the Phoebus. There were but three survivors.

Seventy-three men had been lost—the worst aviation disaster to date. Tragedy was compounded when, on 4 April, the blimp J-3 crashed off Beach Haven while assisting the search for Akron survivors. Two more lives were lost. Again the nation’s press headlined an airship disaster; the New York Times front page was crowded with the story:

73 LOST IN AKRON CRASH, 3 SURVIVORS HERE; SHIP DRIVEN DOWN IN STORM, CAUSE IS UNKNOWN; RESCUE BLIMP FALLS, 2 DROWN, 5 ARE SAVED12

Bewilderment prevailed at the Navy Department, particularly at the office of Chief, Bureau of Aeronautics. Rear Admiral Moffett was removed from the helm of naval aviation. Many members of Congress foresaw the end of lighter-than-air construction for national defense. Others, including SecNav Claude A. Swanson and the House Committee on Naval Affairs, refrained from predictions. At Lakehurst, the wives and families of the lost men waited stoically for hopeful bulletins that never came. And the officers and crew of Macon waiting in Akron were in shock. So many of their small family had been taken away.

The naval court of inquiry implicitly censured Commander McCord for not having avoided the severe conditions Akron encountered. But this was too easy. The severity and extent of the general storm conditions on 3–4 April were a surprise to the Weather Bureau and, thus, likewise to Lakehurst and to Akron. The decision to take off that night must remain a point of argument. But for whatever reasons, a powerful down draft or a false reading on Akron’s barometric altimeter, or both, Akron was flying too low. Inclined by the tail, moreover, her lower fin was even closer to the sea. Indeed, at an angle of twenty degrees, the control car would still be about one hundred sixty feet above the water if her lower rudder were touching the surface. The Akron had literally flown into the sea. The fact that there were no life jackets and only one rubber raft on board doubtlessly contributed to the heavy loss of life. A few sensed it at the time: the Akron disaster was the beginning of the end for the naval rigid airship.

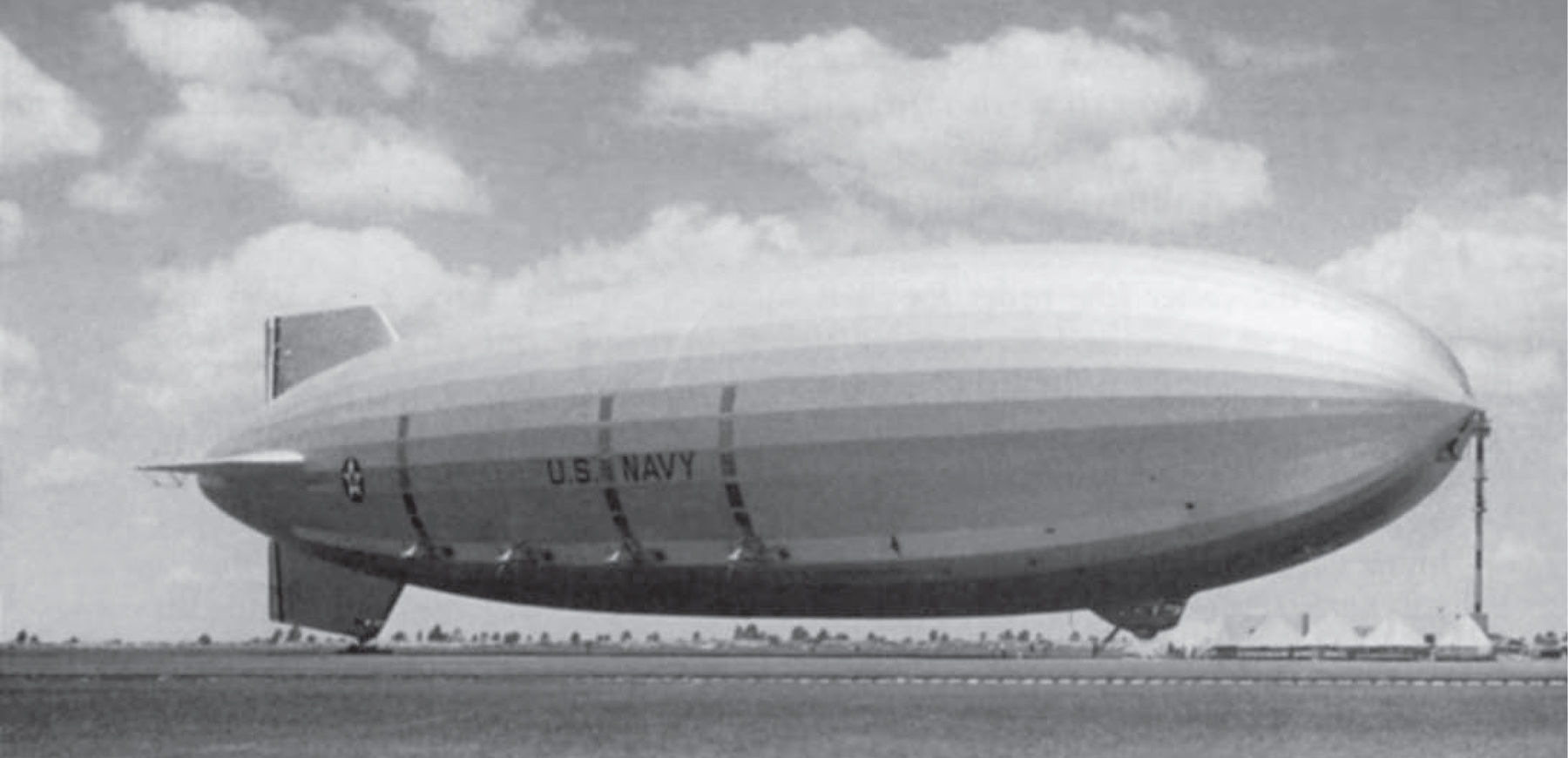

The main structure of USS Macon had been completed by the summer of 1932; the ship was christened on 11 March 1933 by Mrs. William A. Moffett, wife (and soon-to-be widow) of the chief of BuAer. To all outward appearances Macon was virtually a copy of her sister ship. In length, height, volume, and power plant, the two ships were identical. The external differences were very few. Macon’s radiators and water recovery gear were streamlined into the hull to reduce drag. (The radiators on Akron had been mounted on the propeller outriggers.) And Macon’s outriggers were equipped with a cowling, again to reduce drag.

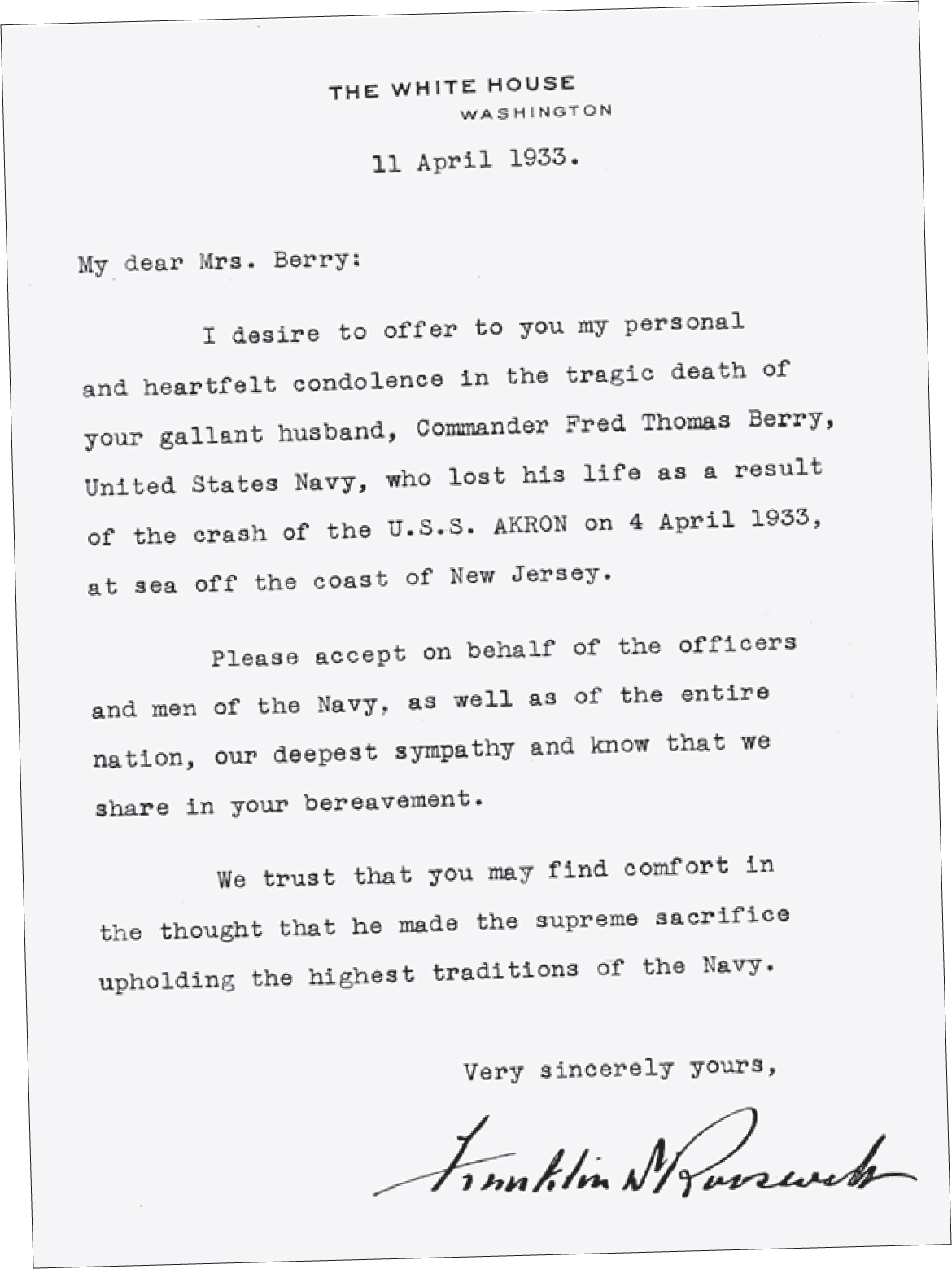

Letter from FDR. Loss of Akron, Admiral Moffett, and the talents and skills of seventy-two other personnel were to prove irreparable, the beginning of the end for large-ship development, naval and commercial. L. Berry

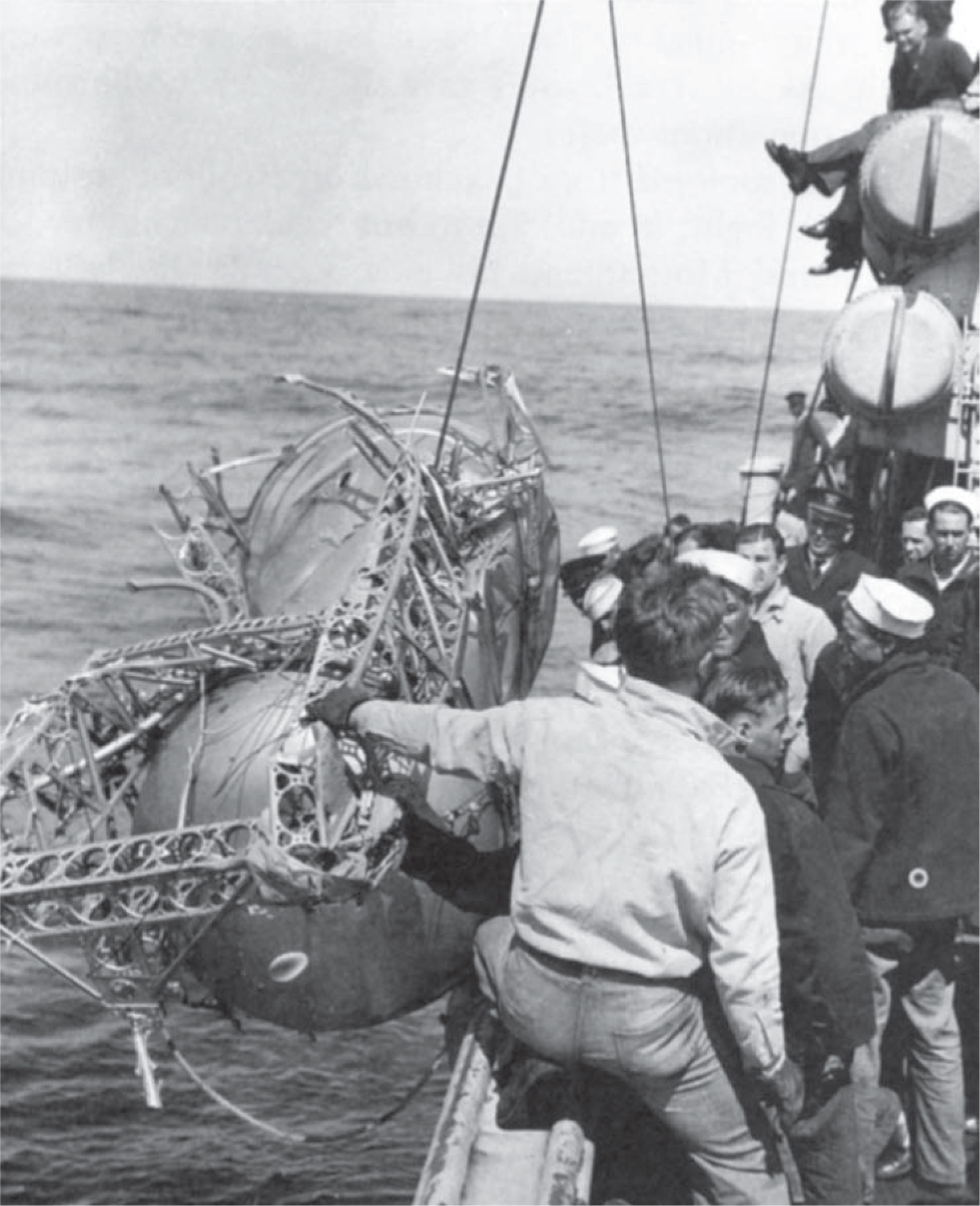

Wreckage from ZRS-4 is hauled aboard USS Falcon, April 1933. Akron went down in 105 feet of water about thirty miles seaward of New Jersey. That all but three shipmates had died “had a [sobering] effect that is difficult to describe” for those with orders to Macon. The psychological damage in Depression-era America was incalculable. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

However, many alterations had been worked into the structure to increase efficiency and to save weight. These ranged from changes in the radio system, telephones, and electrical generating system to rearrangement of Macon’s bunk rooms. Indeed, Macon was approximately eight thousand pounds lighter than her predecessor and, thanks to cleaning up of her hull lines and new propellers, three knots faster. Her trapeze was an advance over Akron’s and, unlike Akron, her hangar and trapeze were complete when she left the factory.

In the predawn hours of 21 April 1933, Macon crewmen prepared her first flight. The doors of the Airdock opened at 0510; minutes later, the new ZR was undocked into a chilly wind. At 0602, as reporters, photographers, radiomen, Goodyear publicity men, and well-wishers watched eagerly, Commander Dresel gave the order, “Up Ship!”

This was the first of four test flights before commissioning. On 23 June the INA notified Dresel that on behalf of the United States, he had preliminarily accepted the ship and given the contractor a receipt for the vessel. At 1403 Rear Adm. Ernest J. King, the new chief of BuAer, read the order placing the ship in full commission. Dresel then read his orders placing himself in command, and the ship’s colors and commission pennant were broken and the watch set.

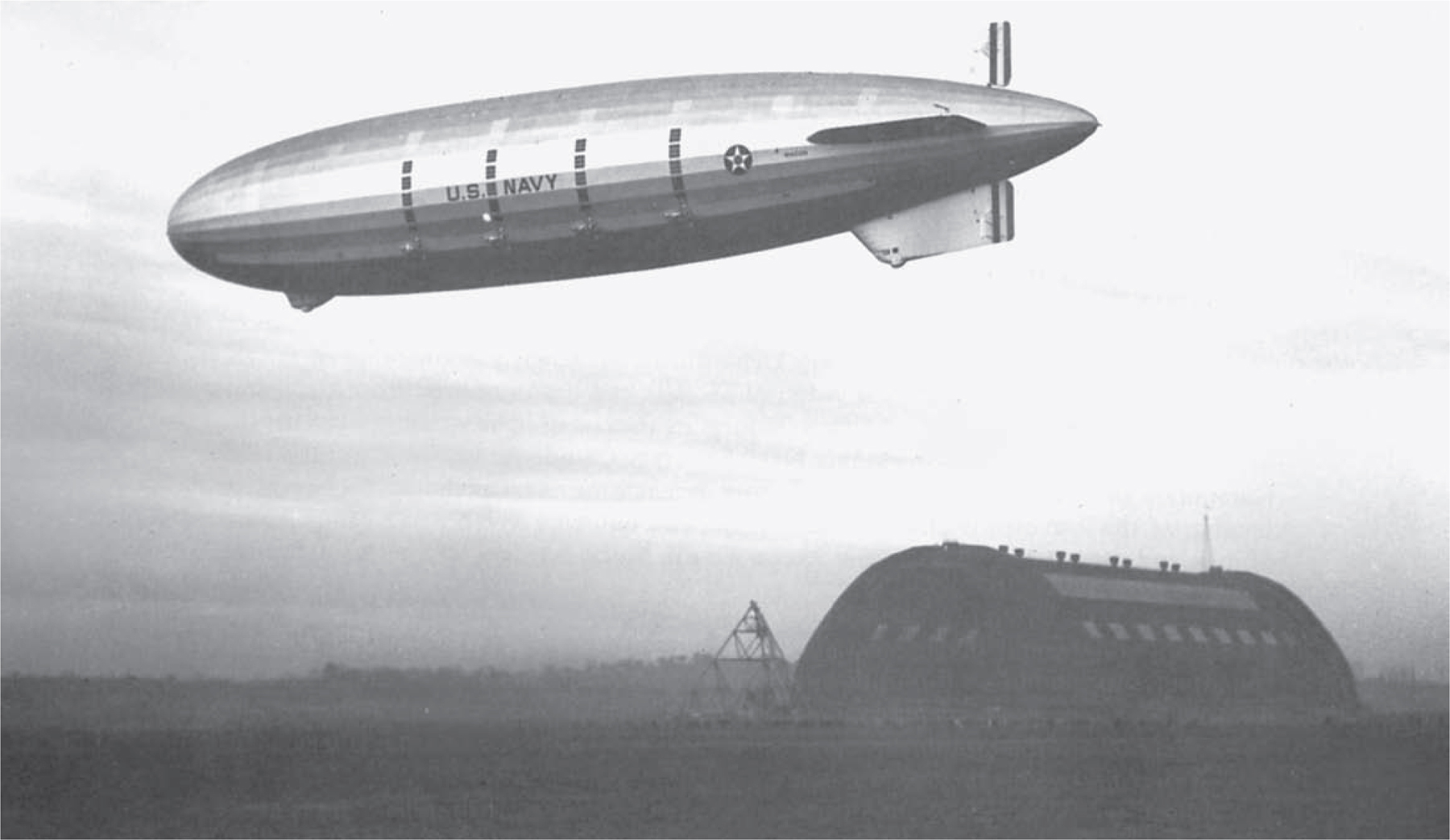

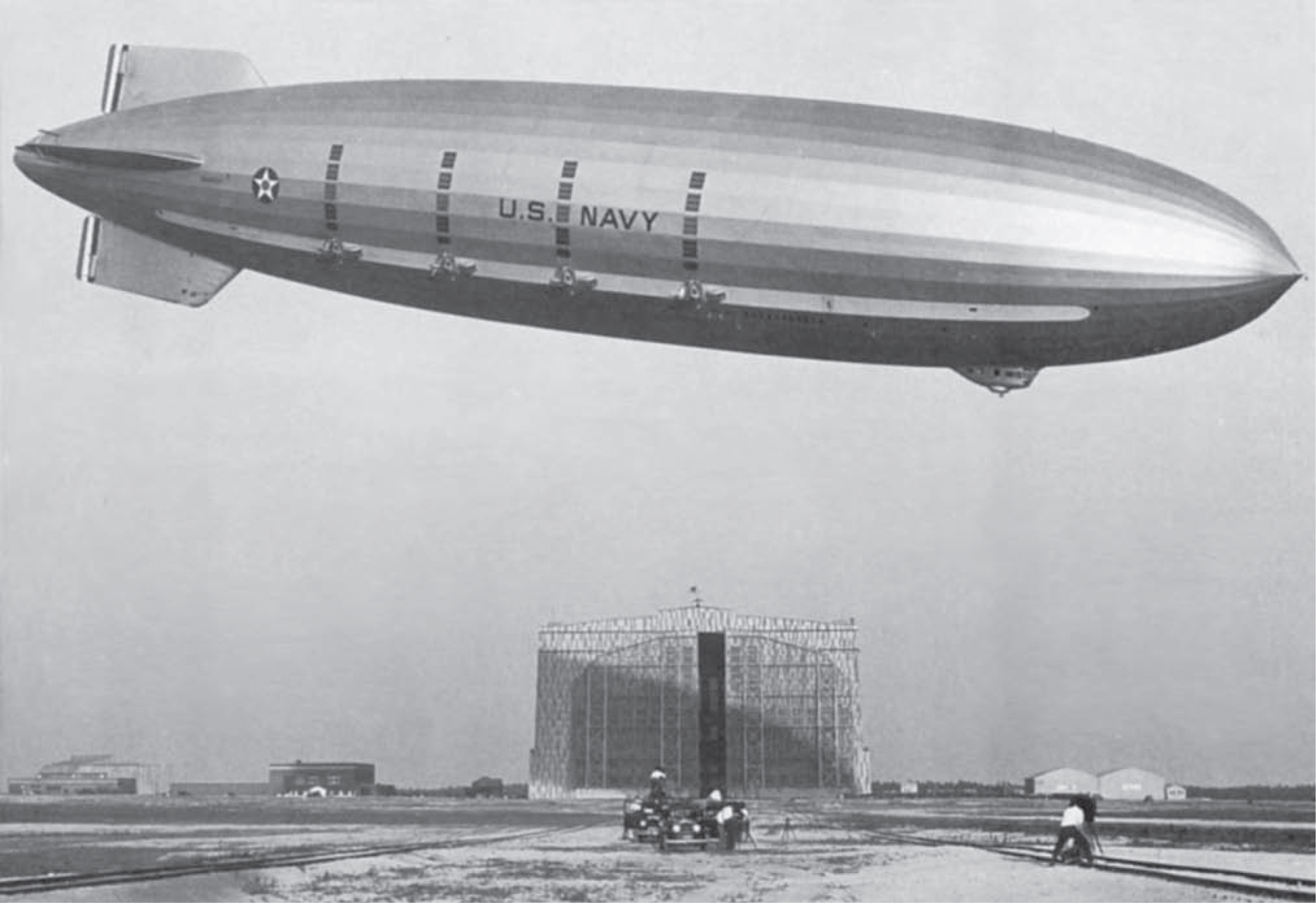

Macon, ZRS-5, takes to the air, 21 April 1933. In significant particulars—length, volume, power plant—Macon was identical to Akron; the external differences were few. Still, alterations had been worked into the new ship to enhance efficiency and to save weight. On board, the flight crew was gratified at the improvements based on experience with Akron. Capt J. C. Kane, USN (Ret.)

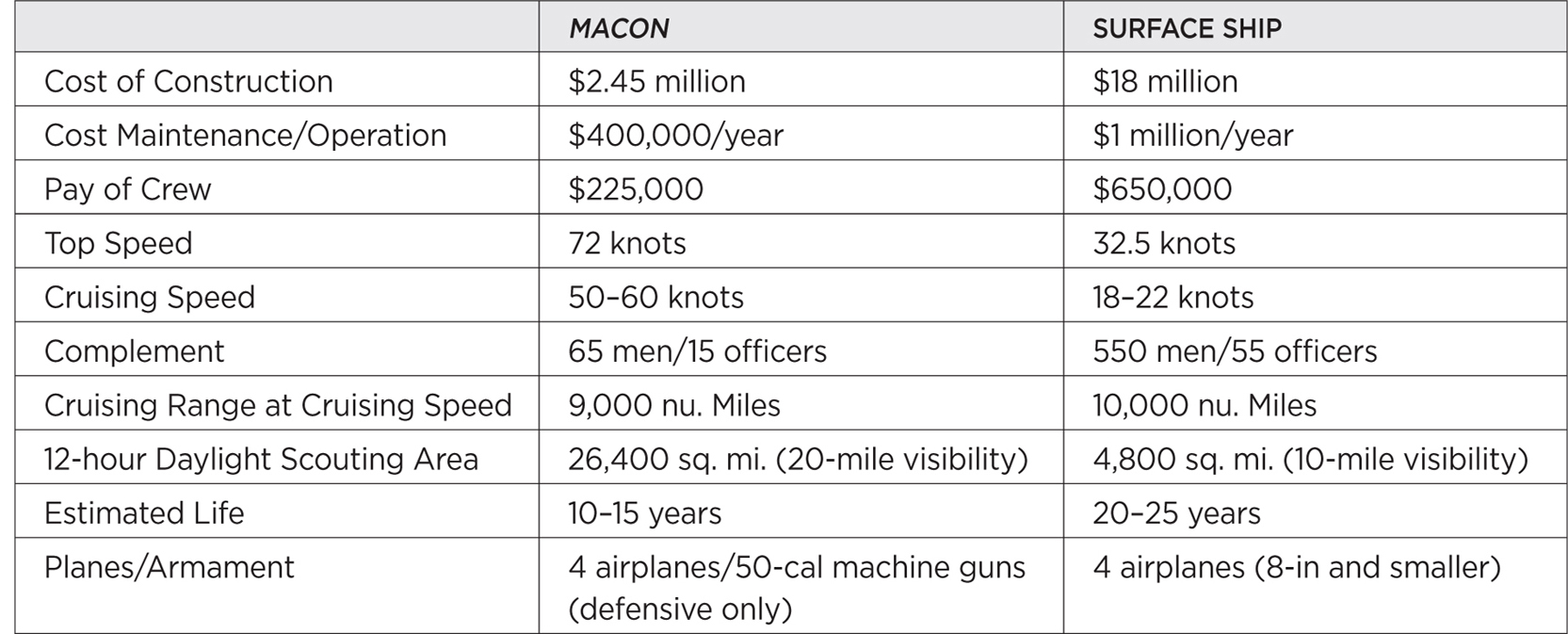

The fleet-type airship scout ZRS-5 compared to a new 10,000-ton treaty cruiser. Surface cruisers were the conventional scouts for the fleet. Though relatively fast-ranging to scout oceanic distances in search of an enemy force, the ZR was no substitute for a cruiser’s gun power. Capt. G. Fulton, USN (Ret.)

Macon’s bridge, portside. Above and left of the elevator wheel and its instruments is the master wheel for all eight maneuvering gas valves and, just below, the toggles for opening and closing individual valves. The water ballast board is at upper right, service toggles just below, and, somewhat lower, the emergency ballast toggles. The two instruments at right are an air temperature meter and a superheat meter. Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

Macon was ready for Lakehurst. The flight crew embarked at 1900; at 2021 Macon was unmoored. She was soon at forty-five hundred feet, cruising along the Pittsburgh-Philadelphia airways en route to Lakehurst. At 0320, 24 June 1933, Macon arrived over the naval air station.

A series of local trial flights followed her delivery including, on 7 July, a rendezvous over New Egypt, New Jersey, with four of her F9Cs. The HTA pilots were then drilled in hooking on to Macon’s trapeze for the first time. The airship’s official trials took place at the end of August, and ZRS-5 was formally accepted. But Macon remained at Lakehurst less than four months. By October the ship was ready for the West Coast and her new home port at Sunnyvale, California. Experimental projects were under way or anticipated with Akron, so BuAer had wanted her close by. Moreover, Macon represented an improvement over her sister ship, and thus she would be more suitable for operations with the fleet. Consequently, on 12 October 1933 Macon departed Lakehurst for the last time. The ship climbed to cruising altitude. On the ground, the drone of her Maybachs faded on the crisp evening air. The air station would never again handle a commissioned rigid airship of the United States Navy.

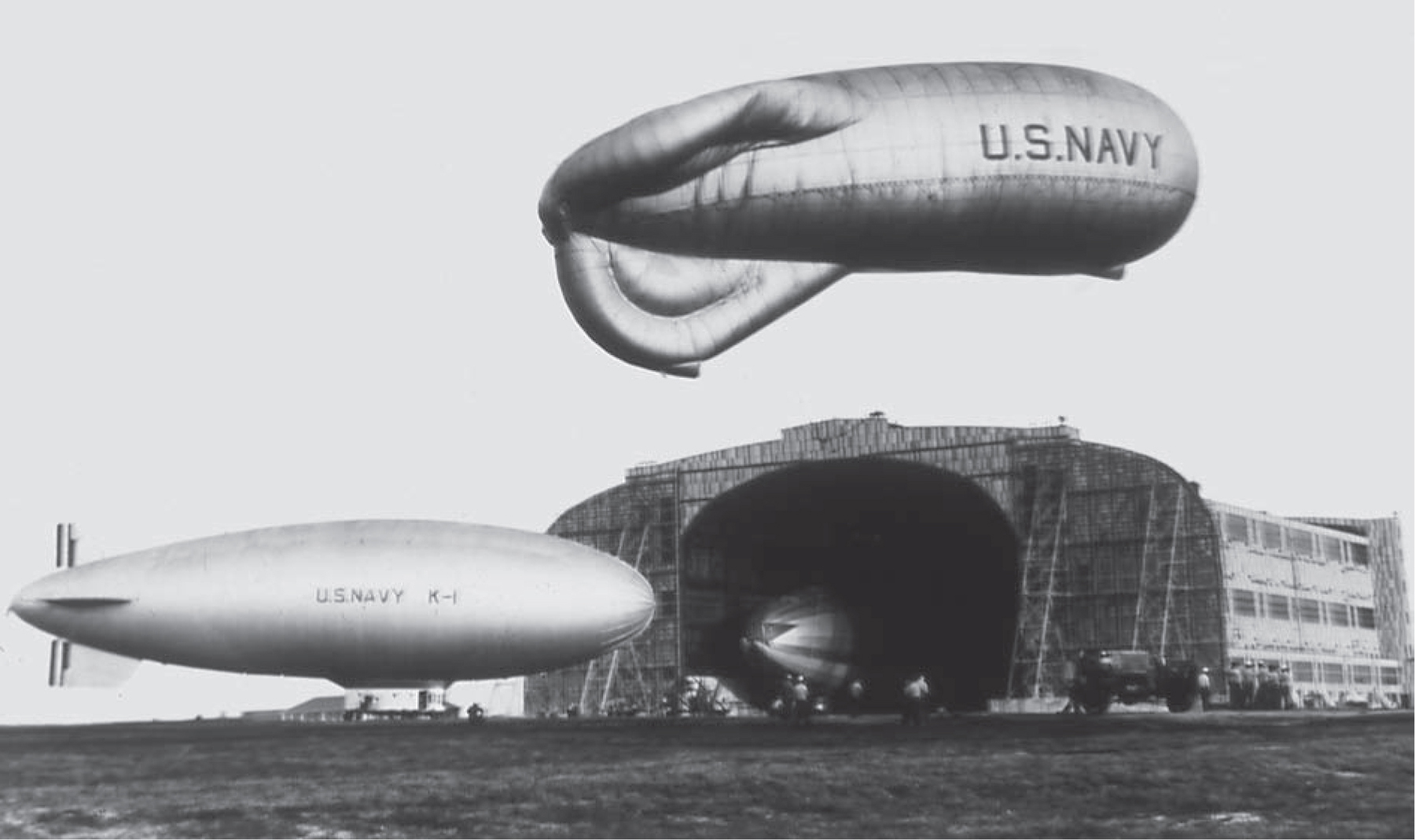

Lakehurst was placed on a restricted operating status by order of the CNO, and all operating expenses were reduced to a minimum. NAS Lakehurst descended into a protracted somnolence. Lighter-than-air activity persisted. K-1, ZMC-2, and free and kite balloons were flown for training. J-4 had already been transferred to Sunnyvale, where she was reinflated and operated until after the loss of Macon. This meager inventory would not increase one cubic foot until G-1 was delivered to NAS Lakehurst in October 1935.

USS Macon moors at Lakehurst, having drilled her planes for the first time on her trapeze, 7 July 1933, two weeks after commissioning. The rigid airship was plagued with the necessity of replacing the weight of fuel consumed. The window-like features above the engines are condensers for water recovery to reduce helium losses through valving. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Macon would base in California; she therefore held to Lakehurst only for her commissioning and official acceptance trials. At 1805, 12 October 1933, Macon was cast off. The naval air station never again handled a commissioned rigid airship of the United States Navy. An era of naval aeronautics had ended at Lakehurst. Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

K-1 and the kite balloon on the West Field, summer 1934. Delivered in 1931, K-1 was the Navy’s first nonrigid with its car suspended flush with the bag. Grounded in 1940 and used as a “dummy” for mooring-out tests, the ship was deflated in October 1941. Shored in the north berth, Los Angeles was being reconditioned for experimental development not involving flight. K. Pace

Overall activity, LTA training included, was cut back. When Class IX graduated in 1932, no entering class was formed for 1933. And in 1934 the Airship Training School (Enlisted Men) was closed. The authorized complement of personnel was reduced that fall from about four hundred to approximately two hundred officers and men and would remain around two hundred fifty at least through 1936. The number of civilian employees also was sharply reduced to save funds.

These were very lean years. Within weeks of Akron’s loss, BuAer had tried to obtain a replacement airship. There was some congressional support for this. A special joint committee, after having probed the loss of Akron and all airship disasters, released its 944-page report in June 1933. Among its recommendations were the immediate construction of an airship to replace Akron and a ship of moderate size for training and research. In the meantime, Los Angeles should be recommissioned for training purposes. But the committee was not Congress. The future would provide very little indeed in the way of funds for the rigid airship. A replacement fleet-type airship to fulfill the requirements of the Five Year Aircraft Program, or a new training ship, were never built.

Navy Day, 27 October 1934. With Akron stricken, the Great Depression deepening, and Macon on the West Coast, Lakehurst remained open on a restricted basis by order of the CNO—operating expenses reduced “to the minimum.” D. Brandemuehl

On 15 June 1933, BuAer recommended that a Board of Inspection and Survey (BIS) evaluate Los Angeles’s material condition. Two months later, the bureau recommended that the nine-year-old ship be placed back in service for training—as recommended by the congressional committee. Thus, in the unhappy summer of 1933, Los Angeles precipitated a paper fracas within the bureaucracy of the Navy Department. One year after decommissioning, on 12 July, the BIS met at Lakehurst “to determine the material condition of the USS Los Angeles and to report on her readiness to resume operations for training service.”13

The report, submitted that September, was generally unfavorable to resumption of flight operations but failed to find any specific evidence of structural deterioration. Nonetheless, after citing limited returns that might be expected from her use merely as a training craft, the BIS concluded that further expenditures on Los Angeles were not justified. The airship’s value for experimental projects in either a flying or nonflying status was not considered, and her disposal for sale or scrapping was recommended.

With benefit of hindsight, it is possible to see the 1933 BIS report as an instrument to help dispose of naval airships. BuAer took issue on nearly every point and insisted on its recommendations that Los Angeles be recommissioned. The Navy Department, indifferent-to-hostile regarding airships, continued to beg off by citing the 1933 findings as to her material condition and usefulness.

On October 13, Admiral King was advised that Los Angeles was to be disposed of by sale or by scrapping after removal of useful items from the aircraft. It seemed that time had run out on Los Angeles. But she possessed remarkable powers of survival and even as a grounded aircraft held off destruction for another six years.

Throughout his tenure as chief of BuAer, Admiral King believed that the rigid airship retained a useful naval function. While the department pondered final disposition of the ship, the bureau, through King, pressed for renewed operations with Los Angeles. In February 1934, SecNav relented somewhat and granted authority “to use the Los Angeles for experimental development to as great an extent as is practicable in a nonflight status.”14 That March, the bureau called for detailed suggestions regarding experimental uses for the grounded ship. By June, Lakehurst’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Rosendahl, was studying and correlating the responses. In July, an experimental program was outlined to the Bureau.

King quickly endorsed Rosendahl’s program, but he again recommended resumption of flight operations. Flight status would ensure maximum scientific return from the experimental program already approved and gain also appreciable training and experience. The cost for one year’s activities: less than $85,000. It was not to be. That same autumn the Navy Department decided against renewed flight operations with Los Angeles, primarily for reasons of “the unjustifiable hazard entailed.”15

But the experimental program was still on the books. In mid-August 1934 a project order for reconditioning Los Angeles for a non-flight program of experimentation was granted. The work was under way by early September. Reinflation was deemed essential. The reconditioning consisted of a thorough inspection and refurbishing; upon completion, Los Angeles was close to ready-for-flight condition. This was desirable in terms of scientific return from the test program, but it was not without calculation. The bureau retained its desire to again fly the ship. It was a hope never realized. The reconditioning and reinflation cost the Navy about $35,000 (including all helium) and was completed by mid-December 1934.

On 18 December—for the first time in two-and-a-half years—Los Angeles was undocked and towed onto the West Field for a brief test of her mooring-out equipment. Beginning in March 1935 and at irregular intervals during 1935–37, Los Angeles was out on the field for a host of experiments, tests, and measurements as the venerable ship swung to the mast. Los Angeles continued to serve—this time as a grounded, full-scale test bed and classroom. But on the morning of 18 November 1937, ZR-3 was moored out for gust-structure measurements and berthed again late that afternoon. Los Angeles never again left the hangar.

ZR-3 is the sole aircraft to have had all the naval traditions of decommissioning. Concluding a thirty-month hiatus, here L.A. is undocked 18 December 1934. Throughout 1935–37, the ship would be shunted onto the field for full-scale tests, checks, studies, and measurements deemed useful to the lighter-than-air branch of the naval service. NARA

NAS Lakehurst was not now center stage. The years 1933–35 were focused on the West Coast and on Macon. Indeed, as the only commissioned rigid in the Navy, the future of the large naval airship was riding with her.

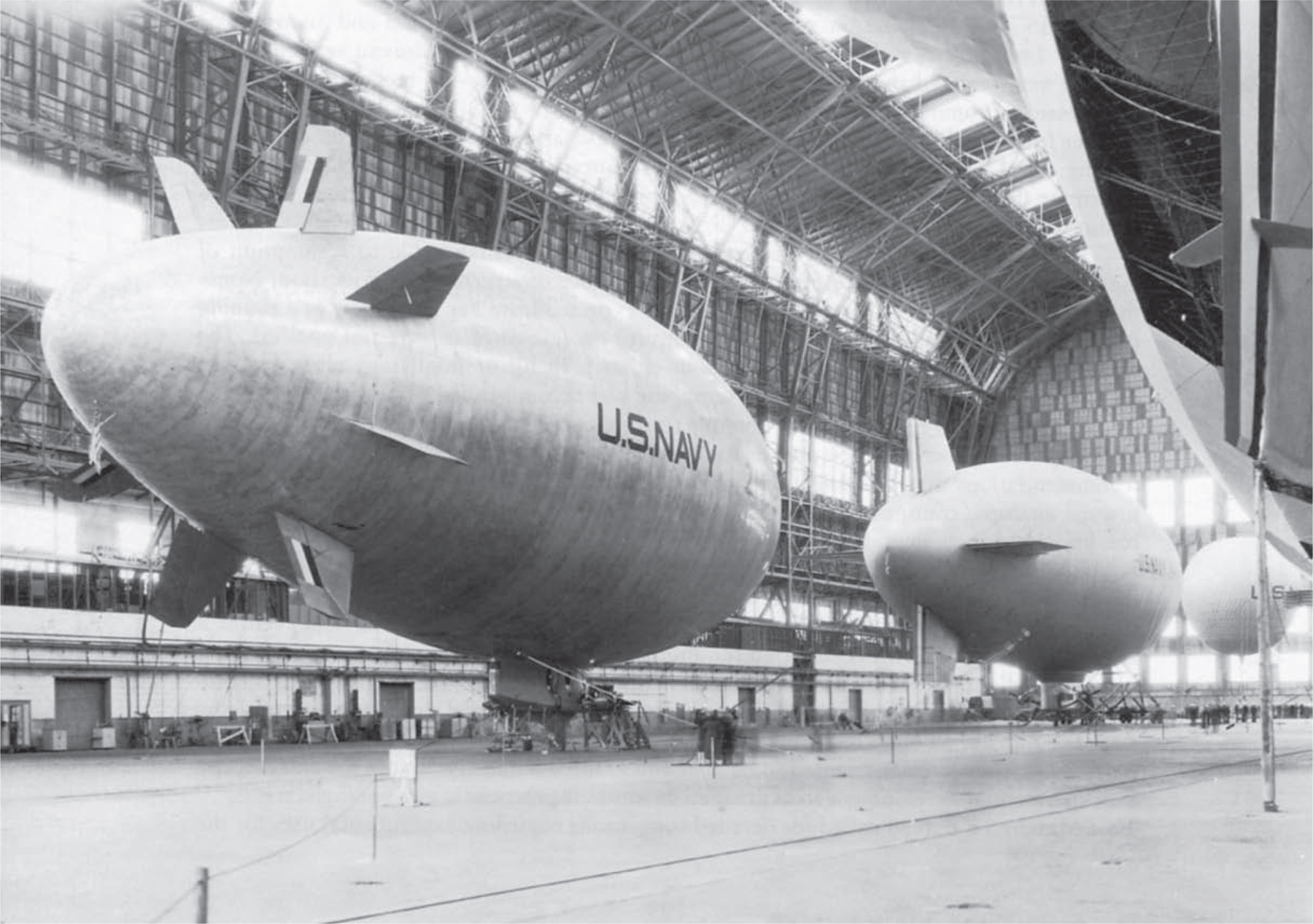

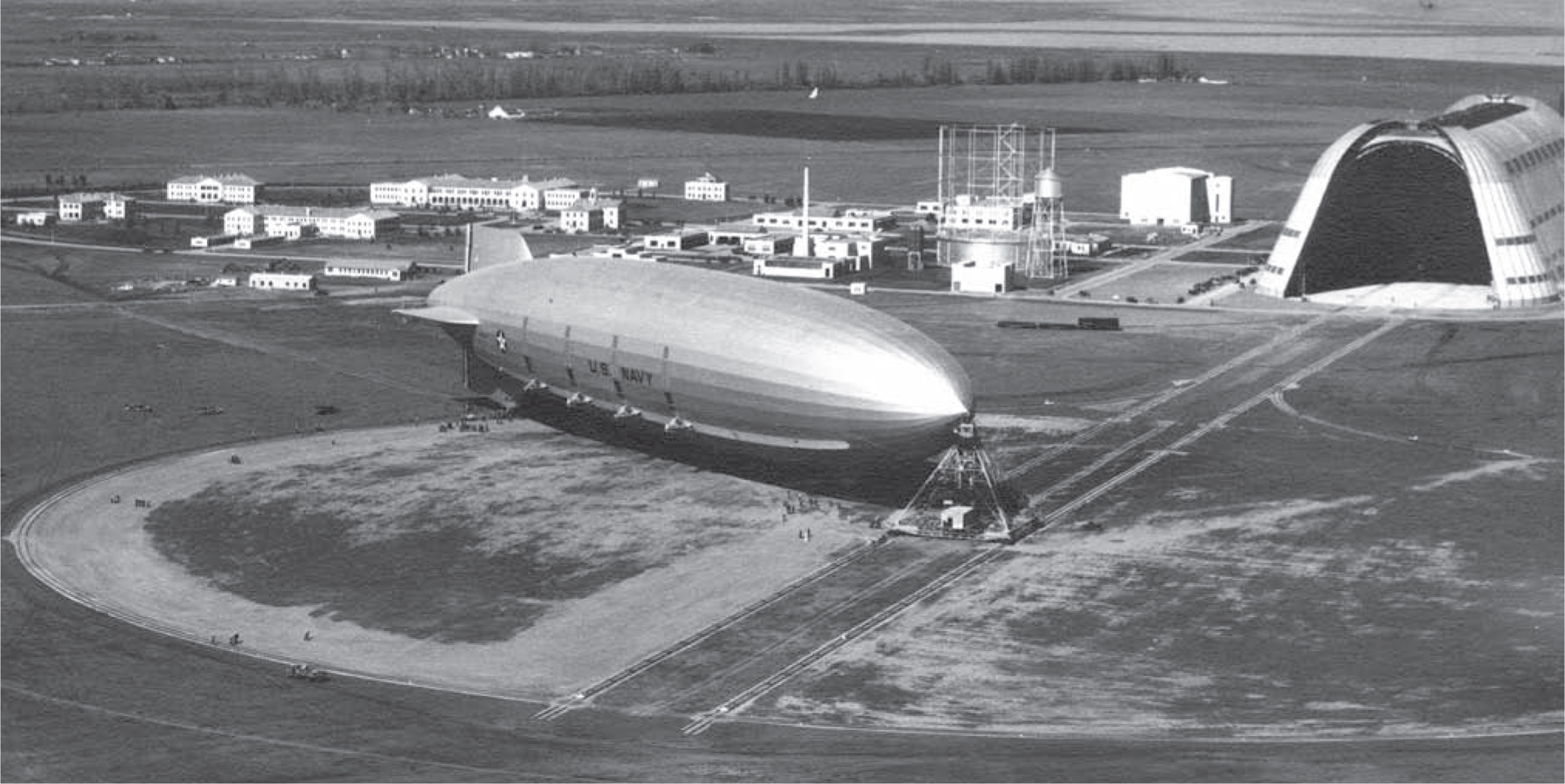

Macon had departed Lakehurst on 12 October 1933. After a demanding 73.5-hour transcontinental passage, ZRS-5 hung over the U.S. Naval Air Station Sunnyvale, California. Macon’s new, modernistic home port was probably the finest lighter-than-air base in the world. The latest word in berthing and ground-handling gear were available here: a sleek hangar with orange-peel doors similar to the Airdock in Akron, a single mooring circle at each end, a stern beam, rail mast, and docking rails through Hangar No. 1. Unlike that at Lakehurst, Hangar No. 1 here had been built with its axis parallel to the prevailing winds, thus eliminating the cumbersome double-circle system needed in New Jersey. Three runways were provided for HTA operations. Weather conditions for mooring and ground handling proved to be ideal compared to those prevailing at Lakehurst.

NAS Sunnyvale, (renamed Moffett Field). Concluding a 73.5-hour flight west, USS Macon arrived over her new homeport on 15 October 1933—one of her F9Cs flown aboard as ballast to assist the landing. The future of the large naval airship was riding with her. From the day Macon arrived, Moffett Field had only sixteen months in which to serve its planned function—a complete servicing facility for rigid airships. R. G. Mayer Collection courtesy Ian Ross

Ground handlers on “spider” lines as Macon’s lower fin is secured to the stern beam, 19 June 1934. Preparatory to docking, the beam would be transferred from the track of the mooring circle to that leading into the hangar. Note the size of the aircraft and the auxiliary control room in the fin’s leading edge. Capt. J. C. Kane, USN (Ret.)

Ship’s crew, USS Macon, commanding officer Cdr. Alger H. Dresel, USN. The flight list typically was made up of ten officers and fifty enlisted men: officers, deck force, engineers force, administration personnel (radiomen, cooks, mess boys), and the HTA unit. USN

On orders from the CNO, Macon was pressed into fleet exercises created to simulate war situations along the California coast. The airship was to be employed to the fullest extent possible in order to determine her military value.16 Thus, in the eight months between Macon’s arrival at Moffett Field and summer 1934, the ship participated in seven fleet exercises, including Caribbean waters that April and May. This required a perilous west-to-east transcontinental trip during which Macon suffered structural damage, including signs of progressive girder buckling aft, near the port fin. Emergency repairs and reinforcements were completed while under way; likewise, on the expeditionary mast at Opa-Locka, Florida, more permanent repairs were effected to damaged girders prior to carrying out assignments to seaward. Upon return to California and homeport, via official channels, a dry-docking was recommended to the CNO to allow for extensive overhaul and for installation of reinforcements in certain parts of the ship’s structure, aft. CNO disapproved these recommendations.

The American Southwest from a portside engine room, USS Macon, April 1934. The ship is en route to Florida for fleet exercises in Caribbean waters. At midday, 21 April, negotiating a mountain pass in west Texas, the ship, heavy with all engines rung-up full power, was hit by a gust of terrific force that broke two girders aft and buckled others. Temporary repairs and reinforcements were made, but the weakness revealed in her tail would end Macon’s career. Mrs. W. F. Bucher

Macon at Opa-Locka, FL, base of operations during Caribbean maneuvers, 8 May 1934. Here Goodyear personnel and the ship’s crew worked to affect a more permanent repair to damaged structure. Akron had moored here in 1933 for flights to Cuba (January) and to Panama (March), as it was a prospective winter base. Skipper Cdr. Frank McCord, USN, remarked “The weather here is perfect for flying.” Squalls and abrupt wind shifts kept the mast watch busy. Note the tents for officers and crew (right). Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

Macon had logged an exceedingly busy, indeed intensive, operational schedule altogether and compared to the past. A great deal of experience and insight had been gained. Macon had taken her first steps toward operating as a true lighter-than-air carrier. Now very long-range operations would be recommended. Nonetheless, the Navy’s upper echelons would conclude that Macon—and thus the naval airship in general—had failed to demonstrate her usefulness as a unit of the fleet.

There is an instructive comparison here with Akron. Although ZRS-4 had operated only twice with the fleet, Akron had been assigned strategic search problems over trackless, empty ocean—operations exactly suited to her extraordinary range and endurance. The presence of an enemy force was not known, only suspected. It was Akron’s mission to scout for her own forces and locate the enemy if present. The Macon, in contrast, was thrown into a series of crowded tactical situations involving relatively restricted areas of ocean. Not only was the enemy known to be present, but also his general military intentions. This was much to Macon’s disadvantage, but it was in this environment nonetheless that she was supposed to demonstrate military value.

Moreover, despite pleas from Admiral King for a more strenuous operating schedule and for special problems arranged for Macon between exercises, there is little to suggest that the CNO, his staff, or the commander in chief, U.S. Fleet were sympathetic to the difficulties confronting Macon in this crucial trial period. The airship was simply thrown in, with orders to “scout tactically” for whichever force received her services. And she was performing before an audience not favorably disposed toward her. Despite the fleet’s obvious prejudices, these early exercises were an educational experience for ship’s officers. They clearly pointed the way toward improvements in operational doctrine, equipment, and their application to the airplane-carrying airship.

Navigation, and vulnerability in close contact with enemy forces—carrier forces particularly—were the most urgent problems crying for solution. Radical alterations from past practices were required. Under Dresel’s command, Macon’s hook-on planes experienced only limited use and did not operate beyond visual contact with the carrier. Given the then-rudimentary state of radio technology and aerial navigation, this was a prudent necessity. Communication between the ZR and her planes was as yet deficient; nor could the planes be navigated away from the airship. As one result, the scouting front advanced by the platform was a restricted one. If her planes were operating within constant visual contact of the carrier, they were providing little advance warning of enemy surface forces or aircraft. Thus, improvements in radio communications, navigation, and development of a reliable means of homing her planes back to the trapeze were essential. Once these aids became available, the ZR carrier would be able to control her scout planes, which then would be free to operate well out in front of the airship or on its flanks, thereby permitting both carrier and planes to maneuver in response to friendly forces and in reaction to movements by the enemy.

With regard to vulnerability, there emerged only one solution. The lighter-than-air carrier had to remain out of sight when contact with enemy forces was likely and let her planes do the scouting. In such circumstances, the airplanes could best protect the airship by giving her ample warning of enemy approach. Here again, improved in-flight communications and navigation were vital. The Macon and her crew were going full out to demonstrate her scouting capabilities. Under Dresel’s command, deployment of the F9Cs had corresponded to his conservative view of the LTA carrier concept. The airship did the preliminary scouting then broke off to permit her hook-on aircraft to maintain and to develop the contact. Early exercises demonstrated the bankruptcy of the airship itself doing the scouting. Macon had been ruled “shot down” nine times in seven fleet exercises. In her inaugural exercise in November 1933 alone she had been ruled “destroyed” three times, resuming participation as a hypothetical sister ship. By summer 1934 it had become clear that the ZRS should act as a platform from which her planes did most of the scouting. The senior pilots of the HTA unit had always seen the airship for what she was—the means of extending the range of their airplanes. But with few exceptions airship aviators were not about to accept this view. Gradually, however, this concept became the operating doctrine. Under Dresel, valuable if still tentative search tactics had been studied. Several methods of search with Macon’s planes were tried, the first efforts explored to control her airplanes from the airship, and experiments begun with a true radio-direction-finding (RDF) device for Macon and her aircraft. All the elements to forge Macon into an effective lighter-than-air carrier were at hand. It remained to consolidate these elements through an aggressive schedule of operations and command. This transition was signaled on 8 July 1934, when Lt. Cdr. Herbert V. Wiley, USN, read his orders for USS Macon.

Lt. (jg) Leroy C. Simpler at the controls of his F9C. Note the skyhook mounted on the upper wing. “He [Wiley] appreciated what HTA could do,” hook-on pilot Lt. Harold B. “Min” Miller recalled, “and was very quick at all times to go along with any suggestions we had to make. He was receptive to anything that could enhance the value of the airship.” The performance achieved after mid-1934 was never tested in exercises west of Hawaii—a logical place from which to operate. Author

Cdr. Alger H. Dresel, (left), CO, USS Macon (1933–34), with his successor, Lt. Cdr. Herbert V. Wiley, CO, USS Macon (1934–35) at the change-of-command ceremony. In retrospect, the airship’s military trials were neither realistic nor conclusive. Still, the decision against the naval and commercial rigid would prove final. Mrs. F. J. Tobin

“Doc” Wiley had entered lighter-than-air in 1923 and been executive officer to Rosendahl, Dresel, and McCord. His recent experience at sea with the fleet was unusual among senior airship officers, who as a group were rather isolated from the surface Navy and rotated back to Lakehurst after their mandatory sea duty. Thus, he knew firsthand of the fleet’s ridicule of airships and of the Macon’s uneven performance in tactical exercises. Wiley was a man committed to a belief in the efficacy of the rigid airship carrier in the interwar Navy. He therefore was willing to try any proposal that might serve to improve Macon’s performance. This included full exploitation of the F9Cs.

And Wiley was a man in a hurry. On 12 July Macon was unmoored from the north circle for a thirty-four-hour flight to assess his new command. The F9Cs were drilled in hooking on. A search exercise was run with the planes and several tests conducted with an experimental radio homing device. Six days later, at 0925, 18 July, Macon took off from Moffett Field for what was to be her longest flight—eighty-two hours and forty minutes over the Pacific. While maintaining radio silence throughout, the mission was independent long-range navigation and a search to intercept two cruisers en route from the Panama Canal Zone to Hawaii with the vacationing President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard USS Houston. Preparations, including practice dropping packages by the F9Cs, were made in advance and in secrecy. At 1015, 19 July, fifteen hundred miles to sea, six engines were run up to two-thirds speed for release of her hook-on planes to scout ahead.

Around noon the F9Cs identified the cruisers as USS Houston and USS New Orleans. Two tiny aircraft appearing out of the overcast so far at sea was something of a shock to those aboard the cruisers. At 1204 Macon sighted the surface ships and took aboard her planes, which were swung out again to drop two waterproofed mail packages to Houston. As Macon retrieved her planes, then hovered over Houston maintaining the same speed (and lowering the latest newspapers), the president radioed a “Well Done” for a “Fine Performance and Excellent Navigation.” Macon landed at Moffett Field on the evening of 21 July—concluding an admirable demonstration of both men and machine. It was not the last Lt. Cdr. Wiley had in store for his crew and the men on the flying trapeze.

The presidential sortie had inaugurated yet another innovation. En route to interception, Macon’s hangar crew had removed the landing gear from two F9Cs. Under consideration since 1930, this was the first time it had been tried. When Lt. Harold B. “Min” Miller, USN, had himself lowered away and unhooked, he found that the plane reacted “in a most normal manner. It made no difference whatsoever as far as the controls were concerned and it gave us every advantage.”17 The pilot was referring to the removal of about 250 pounds and the drag of the undercarriage, which increased top speed from 176 to 200 miles per hour. Moreover, a dead stick sea landing without wheels would be far safer. A thirty-gallon auxiliary fuel tank replaced the undercarriage, which increased the F9C’s endurance by nearly an hour. From the rendezvous flight on, it was a routine procedure to fly Macon’s aircraft without their landing gear during overwater operations.

The fleet was in the Atlantic that summer and fall, so the interval was devoted to a rigorous schedule of training. Macon logged nearly 150 hours that July alone. Between July 1934 and the first of the year she logged another 789 hours for an average monthly flying time of 131 hours. The intensity of training, drilling, and experimentation in this period was without precedent. Simulated scouting missions were flown repeatedly by the F9Cs. Macon’s lookouts were intensively drilled at battle stations and tactics developed against attacking aircraft. Here the F9Cs simulated dive-bombing attacks while the gun crews trained with camera guns and Macon herself practiced taking evasive action. Frequently, the airship was left out on the field at night to keep the crew familiar with mast operations. Experimental projects included rescue gear for retrieving a downed pilot, a device for picking up water ballast, investigation of a service and utility plane for refueling the airship, and revived tests with the observation car, or “sky basket” device, used but once on Akron. Development work on a low-frequency radio homing device, begun in early 1934, proved to be the answer to most of the communication and navigation problems for Macon and her hook-on F9Cs. The antenna for the set on Macon was installed in the bumper beneath the control car and a combined homing set and radio receiver installed in the F9Cs, its antenna looped around the upper and lower wings. In brief, Macon’s navigation was improved dramatically; soon, the hook-on planes were operating at the limit of their radii, far on the flanks of the ZR carrier, thereby extending its strategic reach until rendezvous with the trapeze.

By 1935 and her final flight, Macon was performing as a true lighter-than-air carrier. With her F9Cs stationed sixty miles on each beam, the ZRS could advance a high-speed, high-endurance scouting front approaching two hundred miles—an extraordinary performance for the time. In 1935 there was not a military airplane in the world that could provide a comparable capability. Discussed among the officers about the ship’s potential: a non-stop round-trip flight from Sunnyvale to Hawaii. After repeated pressure from Admiral King, the CNO reluctantly recommended that Macon prepare a schedule of flights between the West Coast and Hawaii. Fleet Problem XVI, slated for spring 1935, would deploy the fleet west of the island chain. There ZRS-5 could fully exploit her unique (strategic) capabilities. Unfortunately for the naval airship, this hopeful picture was riding solely on Macon.18

Chief Aviation Machinist’s Mate (ACMM) C. S. “Chick” Solar, survivor of the ZR-2 detachment, at a dial-system phone, station frame 170, port keel, USS Macon. Note ship’s box-girders, cell no. 8 overhead, a 2,000-pound-capacity fuel tank and, forward, a cell repair kit. Daylight illumination is courtesy of the translucent (unpigmented) outer cover. Standing by is Edward H. Morris, AMM/1c, and squatting is S1c William H. Herndon. Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

Ship’s Cook (1C) William F. Bucher, USS Macon. Crewmen recalled in-flight mess aboard Los Angeles, Akron, and Macon as excellent. Bucher logged virtually every flight of Akron and Macon; transfer to the newer Macon probably saved his life. Note the perforated box girders of the ship’s structure, holes punched to lighten weight, edges flanged to add strength. Mrs. W. F. Bucher

Searches flown by Macon during the fleet exercise of 7 December 1934. The LTA carrier concept represented an instrument of very long-range reconnaissance unavailable by any other means. “We had made great strides,” Macon’s communication’s officer remarked, “in further improving our communications and navigational techniques in connection with operations of our scouting airplanes.” Despite the strategic capability of this expensive machine, Macon was obliged to demonstrate its value to naval warfare in close-range (tactical) exercises. Adapted from Smith, 1965

Since April 1934, Macon had been flying without the tail reinforcements recommended after a near-disastrous structural failure en route to Opa-Locka for Caribbean exercises. Her seventy-four-hour transcontinental trip had presented the usual hazards. But violent air conditions compounded aerodynamic loads imposed by running at full power with the ship heavy through the mountain passes of Arizona and Texas. Over west Texas, Macon found extremely rough air. The men on the elevator wheel had to be relieved at ten-minute intervals, and those on the catwalks were obliged to hold on. One officer in the starboard keel amidships could see the structure twisting in one direction forward and in the opposite direction aft.19 Shortly after noon, 21 April, two diagonal girders broke at frame 17.5 port and another buckled in the main ring in the same area—where the port fin was bolted to the frame. Emergency repairs and reinforcements probably saved the ship. Macon proceeded on to Florida.

More permanent repairs were effected at Opa-Locka before Fleet Problem XV. But after Macon’s return to Moffett Field, on 18 May, fin strength was investigated in depth. It was decided to reinforce frame 17.5 at each of its four fin junctions. But the work was deemed “not urgent” by BuAer. No one was especially concerned. During overhauls between November and February, the reinforcement was carried out, except for the upper parts of frame 17.5 where the upper fin was attached. This was slated for Macon’s overhaul in March. Superb military readiness in early 1935 had been gained at the expense of material condition. The penalty for this trade-off was at hand.

The siren for general assembly on the morning of 11 February 1935 was sounded at 0600. Men tumbled out of their bunks, donned flight gear, and proceeded through the crisp, dreary dawn to the Sunnyvale hangar, already ablaze with light. Inside, Macon awaited her flight crew. The eight engines were warmed. At 0620, the 200-foot-high hangar doors rolled back. Two hundred men and 400 tons of mooring equipment towed the 785-foot airship through the south doors at 0630 to the center of the circle. Takeoff was the last ever logged by a U.S. Navy rigid airship.

During 11–12 February, the fleet was steaming from San Diego and Long Beach north to San Francisco. Macon had orders to use this movement for training in strategic scouting. She was to search for all fleet units, identify them, and maintain a plot of their movements while she and her F9Cs remained unobserved. This operation was exactly suited to her. Indeed, Macon executed her most effective military performance—but this was soon overshadowed.

At 1310, 12 February, Macon received word that she was released from the exercise and was at liberty to head for the “barn.” At 1547, her planes returned from a sweep to the north with Macon following and were secured aboard. Macon continued north.

The watch changed at 1600. Throughout the ship, crewmen shuttled to duty stations as shipmates just off watch sought out a cigarette, a meal, or a card game. There was no indication of trouble. At 1704, the Point Sur Light was nearly abeam. Wiley observed a peculiar cloud condition on the starboard bow and gave the order, “Left rudder.” Coxswain William H. Clarke put his wheel over. At that instant, a strong gust struck, turning and rolling Macon to starboard. The helm was wrenched from Clarke’s hands, and the elevator wheel was torn loose from the grasp of Aviation Metalsmith 1st Class Wilmer M. Conover. The next thirty-four minutes have been described by the commanding officer.

Immediately thereafter [the order for “left rudder”] the ship lurched suddenly as if in a powerful gust of wind, and the control wheels were spun out of the hands of both the rudderman and the elevatorman. The effect of this supposed gust was of very short duration, and for a few seconds it seemed that the men on the controls had recovered control. I asked the elevatorman if his control cables were broken and he replied that he thought that he had control. Within a minute the ship began to incline up by the bow and ascend rapidly. . . . Immediately, word was received in the control car by telephone that number one gas cell was gone. Orders were given and executed immediately to drop all ballast and dropable fuel abaft of amidships. The engines were idled to reduce the strain on the structure of the after part of the ship and to slow the rate of rise. In spite of the dropping of ballast, the inclination upward increased to at least twenty-five degrees and altitude finally reached almost 5,000 feet by altimeter. Upon receiving information that number two gas cell was deflating, the Commanding Officer directed the radioman to send out an SOS.20

What had happened? The officers in the control car and men near the stern knew that there was a problem aft, but no one knew exactly what had occurred. The upper part of frame 17.5—which had yet to be reinforced—had in fact failed, tearing gashes in cell nos. 1 and 2. With its support weakened, the Macon’s upper fin carried away suddenly, damaging cell zero and inflicting further damage on cell nos. 1 and 2. All three deflated rapidly. The Macon retained a nose-up attitude despite lengthy valving from the forward three cells, the dropping of all ballast and disposable fuel aft, and orders for all hands off watch to proceed to the bow in a futile attempt to regain trim. The engines were exploited to obtain a measure of flying control and to steer, but with little success.

It was physically impossible to keep the ship in the air and the Commanding Officer decided to land upon the sea. . . . The surface of the water was sighted from about 1,700 feet, and the crew was warned to stand by to abandon ship, although by this time all hands had donned life-jackets and carried on their duties . . . available ballast was dropped to ease the impact with the water. . . . The inclination of the ship was about twenty degrees bow up at this time. At about 700 feet the engines were backed briefly to stop headway, and by prearrangement this was the signal to the engine tenders to abandon their stations.21

Macon’s tail hit the sea at 1739. As she gradually sank by the stern, her crew abandoned ship and swam to life rafts thrown overboard during the descent. The USS Macon was observed to sink from view at about 1820. Of the eighty-three persons on board, two were lost. None of the survivors was seriously injured.