Between 1919 and 1935, the large naval airship dominated lighter-than-air aeronautics in the United States. But in 1920 the Navy had assumed responsibility for all rigid airship development. Thus, the commercial future of the rigid airship in America—assuming it was to have any—was likewise in the hands of the Navy Department. This twofold military and commercial emphasis is evident in the Navy’s operation of Los Angeles for “civil purposes.” Indeed, her flights to Bermuda and Puerto Rico in 1925 had been simulations to assess the airship’s commercial value over water routes. But most important for the future, delivery of LZ-126/ZR-3 (Los Angeles) marked the beginning of a close liaison between American and German airship men that would endure until the Second World War and benefit American commercial planning immeasurably. German technology and operational methods were keenly followed in American naval circles. Navy officers were welcomed aboard many of Graf Zeppelin’s pioneering flights. Later, in 1936, at least two officer observers and Goodyear-Zeppelin representatives accompanied each of Hindenburg’s crossings. For their part the German organization used the Lakehurst base and other facilities on their transoceanic crossings to America, and they were not too proud to adopt Navy ground-handling equipment and methods at home in Europe.

The 1928 contract for Akron and Macon had represented an effort by the Navy and Goodyear to found an airship-building industry. It was hoped that ensuing orders from private interests would sustain the art and thus secure a place for U.S. airships in world commerce. Moreover, the Navy’s own experience was expected to yield design, construction, and operational progress directly applicable to passenger- and cargo-carrying rigid airships.

By 1930 Germany’s record of success had stimulated American plans for commercial airship service. Two study organizations were chartered. The American International Zeppelin Transport Company proceeded to investigate all facets of airship travel over the Atlantic. Similarly, the Pacific Zeppelin Transport Corporation explored transpacific commercial possibilities. Each project included prominent representatives from America’s transportation, industrial, and banking communities.

The sum of these investigations confirmed the feasibility of scheduled flights between Europe and North America, 2½ days eastbound and 3 to 3½ days for the return. Weekly service between California and Hawaii was also projected, to be extended later across the Pacific to the Orient.1 Transatlantic plans would rely on a joint German-American organization and called for reciprocal use of hangars, masts, ground crews, and related facilities. Hugo Eckener, chairman of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, the German construction company, and one of the great men of his day, knew that transoceanic air transport would not be possible without American capital and participation. Beginning in 1928, in command of the newly completed Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127), Eckener set out to generate international interest and American backing for commercial air travel by airship. Graf Zeppelin barnstormed throughout Europe and to the Americas, her flights captivating the world’s press and public. Eckener’s aeronautical wisdom and his enormous gift for public relations would, by 1936, nurture worldwide Zeppelin service to a practical reality.

It is little appreciated today that the airship was the first commercial carrier to demonstrate, largely through Eckener’s efforts, the feasibility of transoceanic, intercontinental nonstop air transport. In the interwar years before the DC-3, airplanes of any appreciable payload rarely enjoyed an operating radius exceeding five hundred miles. Yet the airship of the 1920s had a useful lift measured in tons and a range of several thousand miles at fifty to seventy miles per hour. A transportation system that offered this performance could not be taken lightly. Bankers and industrialists of the day appreciated the potential of large airships and followed the German venture with more than casual interest between 1928 and 1937.2

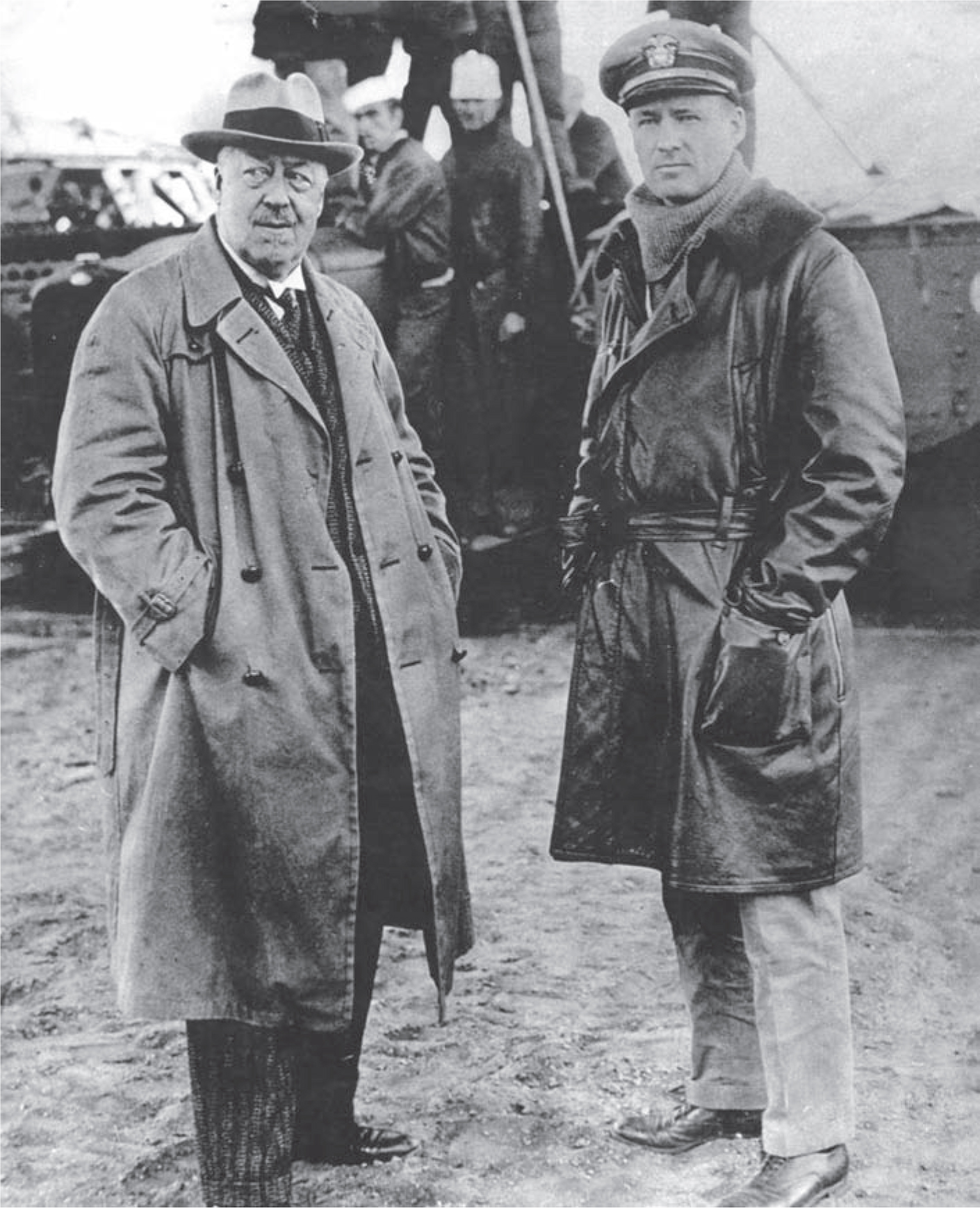

Dr. Hugo Eckener, left, and Cdr. Charles E. Rosendahl, USN. Airship operator par excellence, Eckener’s international prestige would nurture the commercial airship to the brink of public acceptance by demonstrating the feasibility of transoceanic air transport. “Rosie” was the most eminent officer in the LTA branch of the naval service. Tough, competent, and blunt, his contributions were the product of outstanding ability and incessant work. The liaison between American and German airship men was very close. NARA

Beginning in 1930 a series of U.S. merchant airship bills were introduced in Congress. Their passage would recognize the airship as a commercial carrier and thus provide subsidies similar to those already enjoyed by the domestic airlines. In the give-and-take of competing aviation interests in the 1930s, these bills came within a hair’s breadth of approval. Unfortunately for the airship, the lack of subsidies and the unsettled economic and social order undermined Depression-era plans for an American commercial service and would leave only the Navy to operate large airships in the United States.

Opposition, mistakes, bad planning, and bad luck would foreclose commercial operations in America. Yet Germany continued to improve upon its excellent commercial record, an enterprise that began in 1909. In November 1909, nine years after the first flight of a Zeppelin, the Deutsche Luftschiffart A.G., or German Aerial Transportation Company, was founded by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. DELAG, as it was known, represented the world’s first commercial aerial transport company.

A passenger excursion service was inaugurated in 1910. Contrary to the austere conditions prevailing on airplanes of the day, these early airships already boasted an unusual degree of comfort for the paying passenger. The cabin spaces were richly paneled, the floor carpeted, and large sliding windows provided a marvelous aerial view from comfortable wickerwork furniture.3

When the First World War began in 1914, the Zeppelin organization and its assets were promptly integrated into the national war effort. Construction facilities were expanded, and the number of army and navy airships soared. Improved and progressively larger ships were designed and built on a furious schedule using standardized production techniques. Luftschiffbau Zeppelin and its subsidiary companies designed and built eighty-eight airships at four construction plants between 1914 and 1918.

After the armistice, the company was forced to suspend operations and to surrender its surviving aircraft to the Allied powers in compensation for those destroyed by their crews. It was a time of acute crisis for the firm. Struggling to remain viable, the Zeppelin Company turned to the manufacture of aluminum cookware and other items. Its aeronautical expertise remained, however, ready for application.

America had been an interested observer of the rigid airship in Europe. Negotiations between the U.S. Navy and Luftschiffbau Zeppelin to build an airship for the American government had produced Los Angeles. Eckener’s achievement would profoundly influence intercontinental air travel in the period between the wars.

Eckener skillfully exploited this success and the international enthusiasm it had aroused. He had given the German national psyche a tremendous boost. International negotiations to lift restrictions on German civil aviation were deeply affected by his achievement. In 1926, Germany again was permitted to compete in international aviation, including the building and flying of Zeppelins. Work on a new passenger airship for transoceanic service could commence.

LZ-127 was christened Graf Zeppelin on 8 July 1928; the maiden flight was logged on 18 September, Eckener in command. Anticipation of the first transatlantic crossing to America began to build. Finally, on 11 October, the “Graf” rose from the Friedrichshafen airfield for the United States and Lakehurst. Newspapers worldwide headlined the departure. Aboard the 787-foot ship were a crew of forty and twenty passengers, including Lieutenant Commander Rosendahl and six journalists. Ten of the twenty had paid for their flight to the New World—the first ever transatlantic air fares.

The first commercial transit of the North Atlantic proceeded uneventfully—until the morning of the thirteenth. When the ship passed through a squall line, she was pushed upward in violent updrafts. Passengers in the lounge found their breakfasts in their laps. More importantly, the outer fabric of the port horizontal stabilizer was torn away. This was a genuine emergency since fabric tatters could jam the elevators. Speed was reduced, and dramatic emergency repairs were carried out by volunteer crewmen who climbed out into the damaged fin.

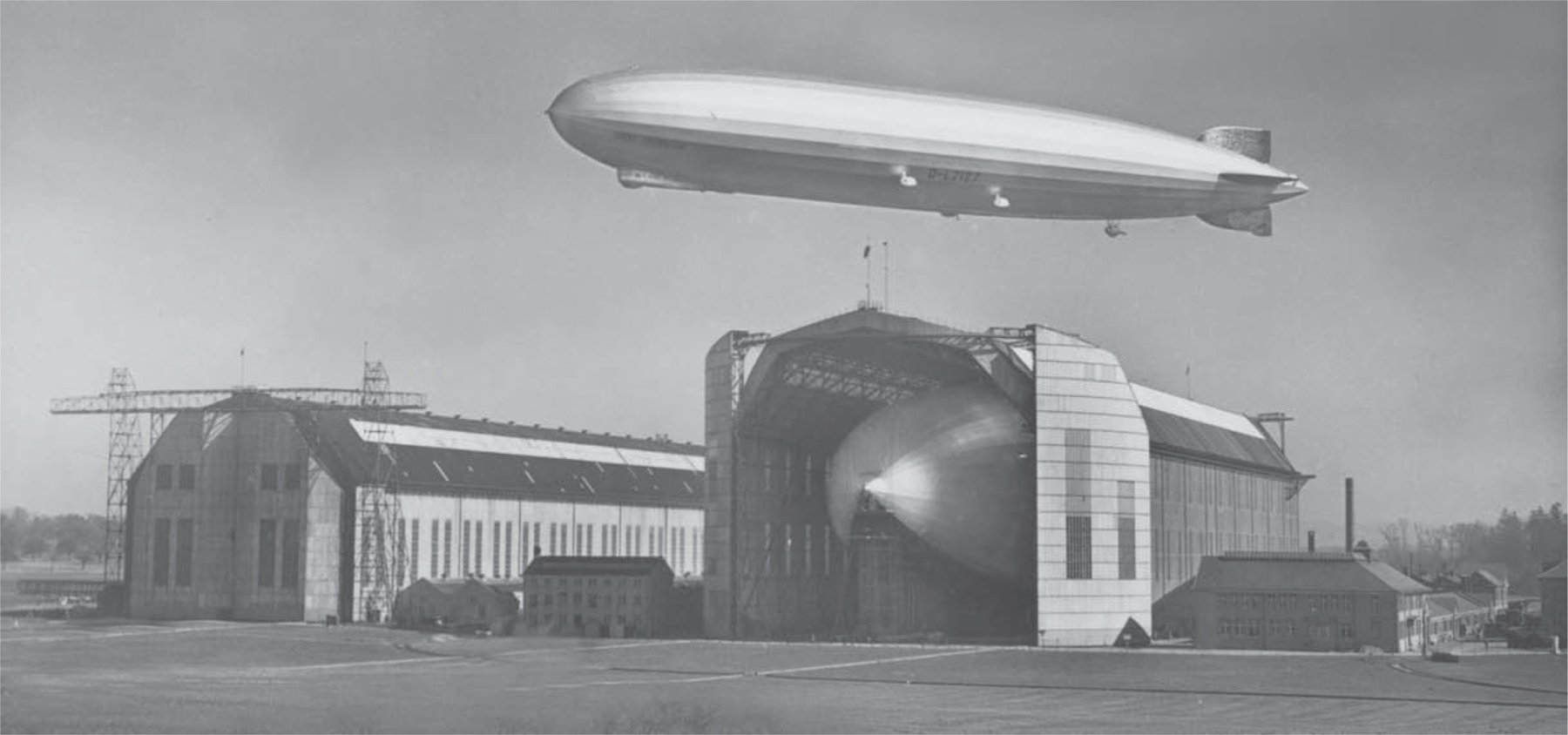

Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127) over Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, Friedrichshafen. DLZ-129 (Hindenburg) was under construction. Graf Zeppelin would call at Lakehurst once in 1928, twice in 1929, and once in 1930 during a celebrated career (1928–37) exceeding one million miles. With Hugo Eckener in command, “127” pioneered the first scheduled air passenger, mail, and cargo service across the Atlantic, logging 143 crossings. Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

News of the damage and radio reports from Graf Zeppelin overheated interest in the crossing. This was genuine drama. Headlines screamed the “life and death struggle” far at sea. For tens of thousands, the impulse to see the airship became irresistible. Cars, buses, and special one-day excursion trains direct to the hangar descended on NAS Lakehurst. Parking inside the gates quickly ran out. Those unable to get inside stopped instead along the roads around the base or began filling spaces rented by Lakehurst residents in their yards and driveways.

The scheduled arrival had been Sunday morning, the fourteenth, so visitors had been collecting since late Saturday. By Sunday, at least sixty-five thousand people were jamming the base—and waiting. Some visitors killed time by inspecting Los Angeles in the hangar. By noon, all available food had been exhausted. And still no official news came from Graf Zeppelin as to its position. By afternoon all roads to and from the beleaguered station were completely blocked as far away as fifteen miles. Sunday waned, and would-be visitors began to camp out. That night, fires could be seen along Lakehurst area roads in every direction.

The great airship made landfall on Monday morning over the Virginia coast. She then steered north over Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Trenton, then to New York City in triumph, a dark hole in the fin plainly visible. That afternoon, as she circled over New York, the metropolitan area became paralyzed. Finally, the Zeppelin flew the sixty air miles south to Lakehurst, arriving at dusk. Thousands of well-wishers were still on the station and watched as four hundred ground-handlers met the ship while dozens of media visitors recorded this singular arrival in America. Finally, after 6,200 miles, 111 hours and 44 minutes, the bumper beneath the control car touched U.S. soil. The Graf Zeppelin was walked under roof and berthed next to Los Angeles.

Graf Zeppelin at Philadelphia, 15 October 1928. Like the space program, the big airships of the 1920s and 1930s were an alluring technology and hence a cultural everyday of the era featured in newspapers, magazines and books, film, radio, and the newsreels, and made into toys. The Graf’s arrival was one of the biggest news stories of 1928. P. Kurisko

An impromptu press conference was held with Eckener in one of the hangar spaces. A tumultuous official welcome followed: a ticker-tape parade up Broadway, a reception by President Coolidge in the White House, other banquets and receptions, and a flood of invitations for the old airman and his ship. It was one of the biggest news stories of 1928. Repairs to the damaged fin and preparations for return to Europe occupied twelve days. Requests for the return passage poured in. And an average of twenty thousand people a day came to Lakehurst to file through the big room and see Graf Zeppelin for themselves.

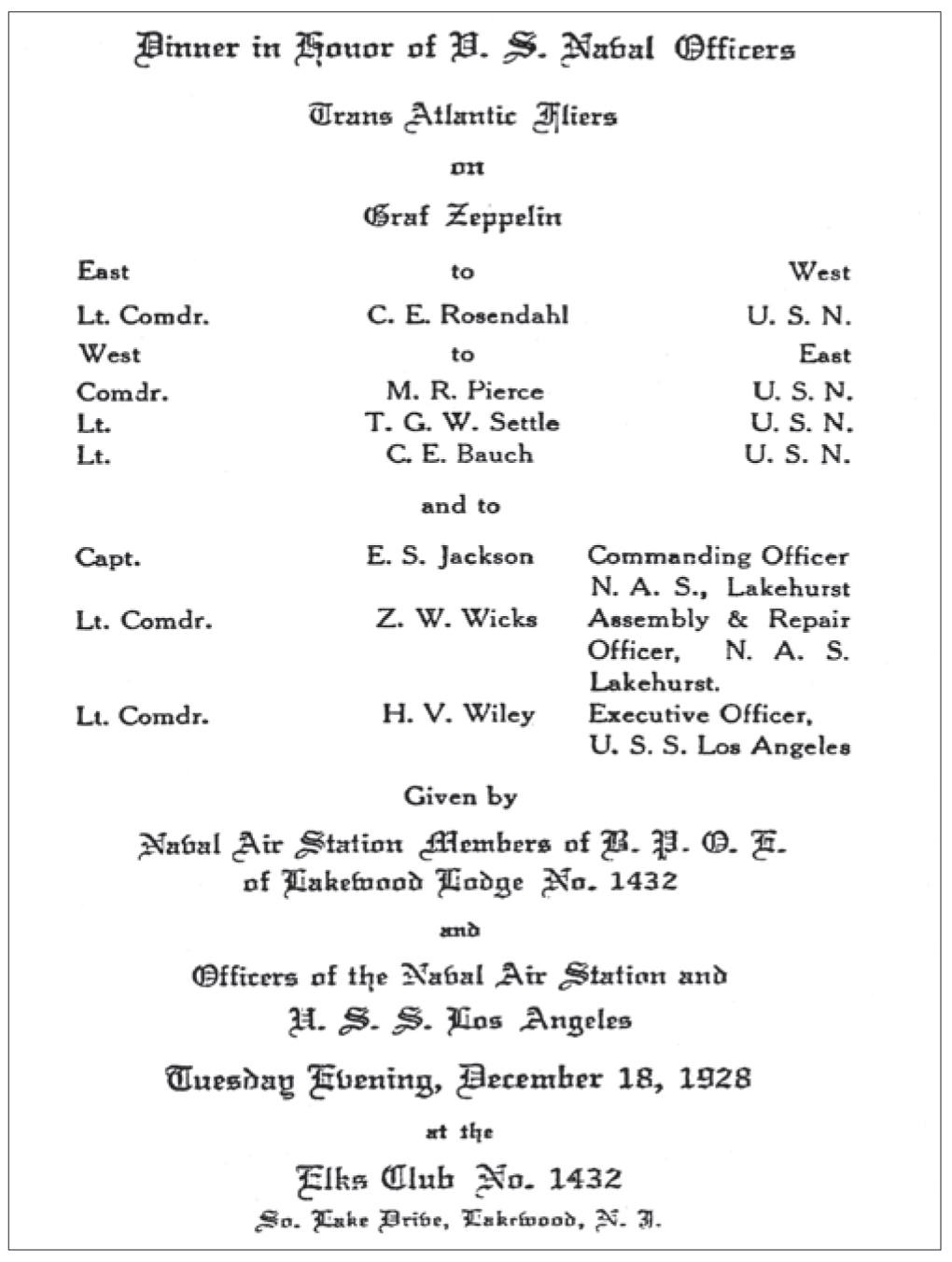

Dinner to honor fellow officers ordered to temporary duty aboard Graf Zeppelin, October 1928. Lt. Cdr. Charles E. Rosendahl was then CO, USS Los Angeles. In addition to developing the ZR’s military potential, the Navy had accepted responsibility for furthering its commercial purposes, the airplane yet unable to transit oceans on a paying basis. Lt. (jg) H. H. O’Clare, USN (Ret.)

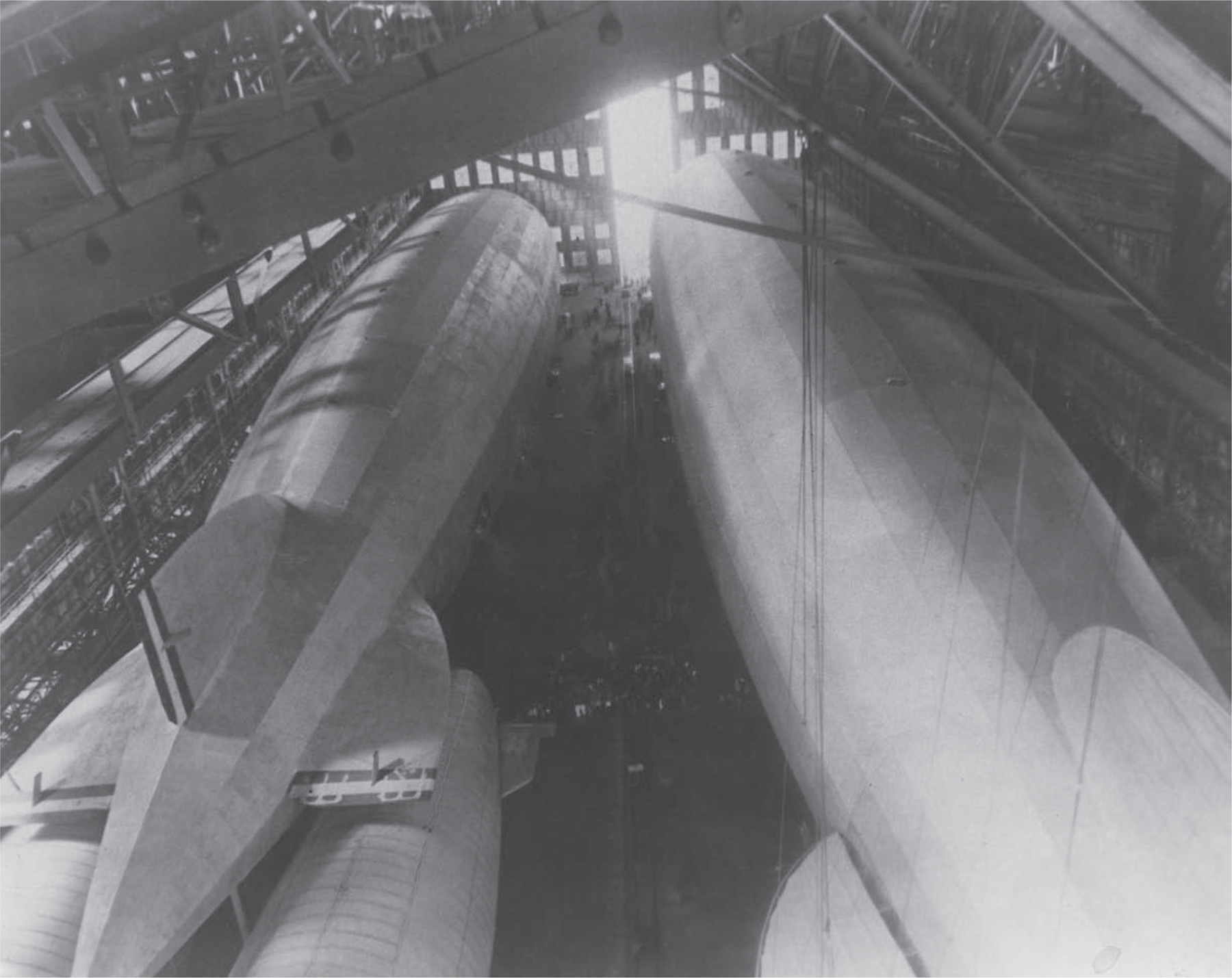

Los Angeles (left) sharing hangar space with Graf Zeppelin at NAS Lakehurst, 1928. Lines to the overhead are being used to repair Graf Zeppelin’s port stabilizer, damaged during crossing. Around 1916, airships and airplanes had stood in approximately the same relative position with respect to technology. In the interwar period, the effort and influence applied to HTA aeronautics would overshadow LTA, including plans for a German-American transoceanic service. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

In the very early hours of 29 October, Graf Zeppelin was undocked from Hangar No. 1 for the first return trip to Europe. On board to complete this first round-trip crossing of a commercial airliner were 25 passengers, 551 pounds of freight, and more than 2,100 pounds of mail. Seventy-two hours later the ship had completed the crossing and arrived at Friedrichshafen.

Thus began the remarkable career of one of the most successful aircraft ever built, a career spanning nine years, 590 flights, and more than 1 million miles. Between 1928 and 1937, Graf Zeppelin would visit five continents, dozens of cities, and cross the oceans 144 times. The ship pioneered the first scheduled air passenger, mail, and cargo service across the Atlantic—in the process generating immense popular enthusiasm that kept Graf Zeppelin in the world’s headlines. This was Eckener’s intention. By late 1934, he was prepared to request American participation in a demonstration service over the North Atlantic.

Eckener took his case to the U.S. government. On 29 October 1934, he made formal application in a statement before the Federal Aviation Commission. In his estimate, service over the North Atlantic was now possible with the same record of safety and reliability established by LZ-127 during the previous four years. The new LZ-129 (Hindenburg), nearing completion in Friedrichshafen, would soon be pressed into service. On the matter of helium, that vital American asset, Eckener considered it “imperative” that the gas be made available to all companies engaged in transoceanic airship service. For their part, the Germans would train U.S. personnel for a joint German-American line and provide every opportunity to acquire the necessary experience over the North Atlantic.

J-3 and J-4 sharing the south berth. Graf Zeppelin concluded a world circumnavigation 29 August 1929. A fantastic demonstration, the flight altered air transport thinking, underscoring the potential of long-distance navigation by airship. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Station personnel and visitors look on as U.S. Department of Agriculture, Customs, Immigration, and Public Health Service officials (Philadelphia district) board Graf Zeppelin to clear the ship. Inspections included passengers’ passports, staterooms and baggage for undeclared merchandise, contraband, and plant pests. A USDA plant quarantine inspector recalled Zeppelin arrivals as “a time of excitement for it was different from the everyday boarding and clearing of ships at the port of Philadelphia.” W. W. Chapman

Graf Zeppelin shimmers like an ethereal machine, 30 May 1930—fourth arrival at Lakehurst. Following a two-day refueling and provisioning, LZ-127 weighed off for Central Europe. Lt. H. R. Rowe, USN (Ret.)

There was of course no privately owned airship terminal in the United States. Application was therefore made to use the Navy’s facilities at Lakehurst on a temporary basis. The American government agreed—with restrictions. The United States would assume no liability or expense whatsoever; the Lakehurst base would be used entirely at the risk of the German operators. Politics confounded these arrangements. Intense domestic resentment against the Nazi government dictated that the Germans pay their way in every respect if charges of special consideration to the regime in Berlin were to be avoided.4 A contract was signed on 11 October 1935.

Plans to receive Hindenburg had commenced at Lakehurst as early as November 1934. For their part, the German builders made several alterations to the nearly completed Zeppelin to adapt it to the U.S. Navy’s handling and mooring equipment installed at Lakehurst. Responsibility for clearing a foreign vessel and its passengers, mail, and cargo fell to the Port of Philadelphia. Arrangements were concluded with the Departments of Agriculture, Customs, Immigration, and Public Health. When the 1936 transatlantic season began, about twenty or so U.S. officials made the fifty-mile drive in time to meet and clear the German airship, a ritual repeated for each of Hindenburg’s ten arrivals from Europe that year.5

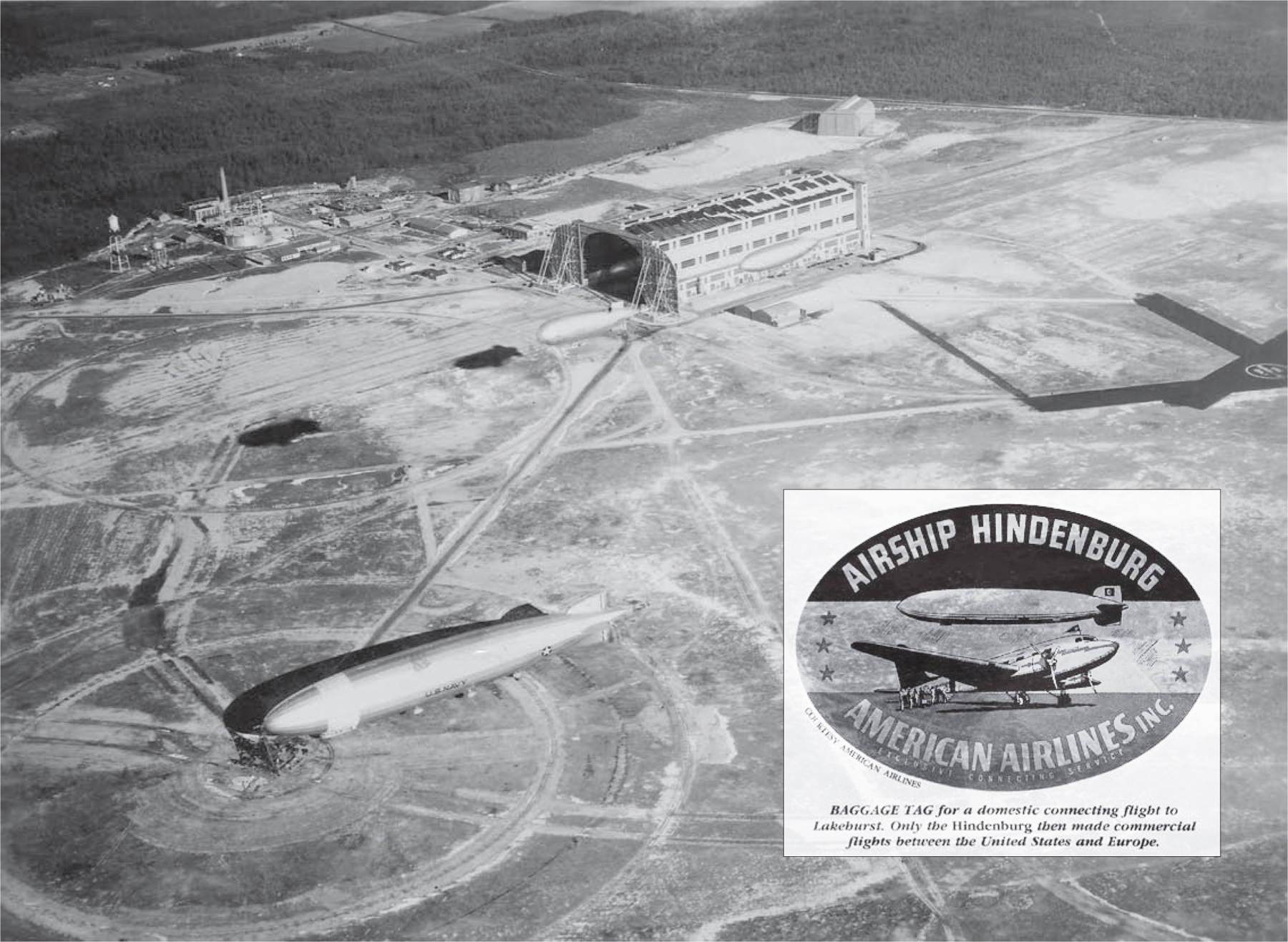

L.A. at circle no. 1, 1935. When the site was modified to receive Hindenburg, another circle and rail connection were graded for her mooring-out program. Note the surfaced runways to accommodate American Airlines’ shuttle connection for passengers arriving by Zeppelin. Mrs. C. M. Ruth

On 6 May 1936 Hindenburg rose silently from the Friedrichshafen airfield to begin the first of ten round-trips to the United States. There were fifty passengers and fifty-five crewmen on board, including three American observers on temporary duty. The ship carried 2,255 pounds of mail and 295 pounds of freight. Total payload on this first North American trip: 13,550 pounds.

The passengers were captivated by this new aerial experience. Several were probably unaware that their flight had even begun. One passenger later recalled that on takeoff “the ground actually seemed to be leaving us, rather than we leaving it; there was no motion. A few minutes in the air and the motors were turned on. There was a very slight incline as we ascended higher and higher.”6 Time seemed to pass quickly; by the very early hours of Saturday, the third day out, and thanks to a tail wind, the ship was fast approaching the American coast.

At Lakehurst, word began to circulate among tired reporters, broadcasters, photographers, and an estimated five thousand hearty visitors that the new Zeppelin would land at approximately sunrise. The airship crossed inland at about eight hundred feet and reached lower Manhattan around 0400 hours. She then cruised uptown past Times Square, Columbus Circle, and Central Park before turning west to the Hudson River and then south past the Statue of Liberty, over Staten Island—and on to Lakehurst. Ships in the harbor blasted a noisy greeting while sleepy thousands made for their windows to see her pass.

About forty minutes later, she was sighted behind the aluminum water tank at the far end of the field. It was then slightly more than sixty-one hours after she had left Germany. She glided over the field and started toward the mooring mast. Hindenburg weighed off to check her equilibrium and gradually descended. At about two hundred feet, the bow mooring cable was dropped. As the ship continued to settle, the after engines were reversed, and the airship eased expertly onto its landing wheel only two hundred feet from the mast.7 After several anxious minutes, the airship’s nose was safely locked into the “flowerpot” at the masthead. She was then towed toward the hangar’s west end. The rail-mast eased the huge ship slowly into berth. At 0624—an hour and sixteen minutes after the mooring line had touched U.S. soil—Hindenburg was safely inside and secured. Minutes later the gangway was down; the first passenger disembarked. At 0741 hours the first of three American Airlines DC-3s roared off with Hindenburg passengers bound for Newark Airport.

For the next three days, Lakehurst held an open house with an estimated seventy-five thousand visitors coming to stare at the famous visitor. While the public admired the ship and the print and radio media generated endless copy regarding the implications of the visit, Navy personnel began cleaning, servicing, and loading Hindenburg for the eastbound leg.

At 2227, Monday, 12 May 1936, Hindenburg rose from the Lakehurst field for the first return flight to Europe. There were 108 persons on board and more than 1,800 pounds of mail. After giving the fifty-three passengers an aerial view of New York City, the ship headed northeast over Long Island Sound, past the Connecticut and Rhode Island shores to Cape Cod on the great circle route for Newfoundland, thence east to southern Ireland. The ship continued to receive all possible weather information throughout the crossing. As the flight progressed, this data was plotted on the navigation chart before a favorable course was chosen. Course might be altered to avoid heavy showers, thunderstorms, and to locate favorable openings along weather fronts (to minimize disturbance to the passengers).8 Altitude over water was usually about two hundred to three hundred meters, but the ship might climb as high as fourteen hundred meters, her pressure height (gas cells full), in search of more favorable winds. The officer observers spent much of their time in the control car noting German operational routine for their subsequent reports, particularly the airship’s navigation from a meteorological point of view. While the U.S. Navy made its notes and kept a studious (and envious) eye on the bridge, the passengers aft enjoyed the splendid accommodations and service.

Hindenburg about to be secured at NAS Lakehurst, 9 May 1936. The first arrival of the North Atlantic season made a deep impression on press and public. The year’s schedule was intended to win support for a joint German-U.S. consortium, building upon the record of Graf Zeppelin. Air station facilities were used under a revocable permit and at the operator’s own risk. The aeronautical question of the hour: Is it possible to inaugurate regular service across the North Atlantic? Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

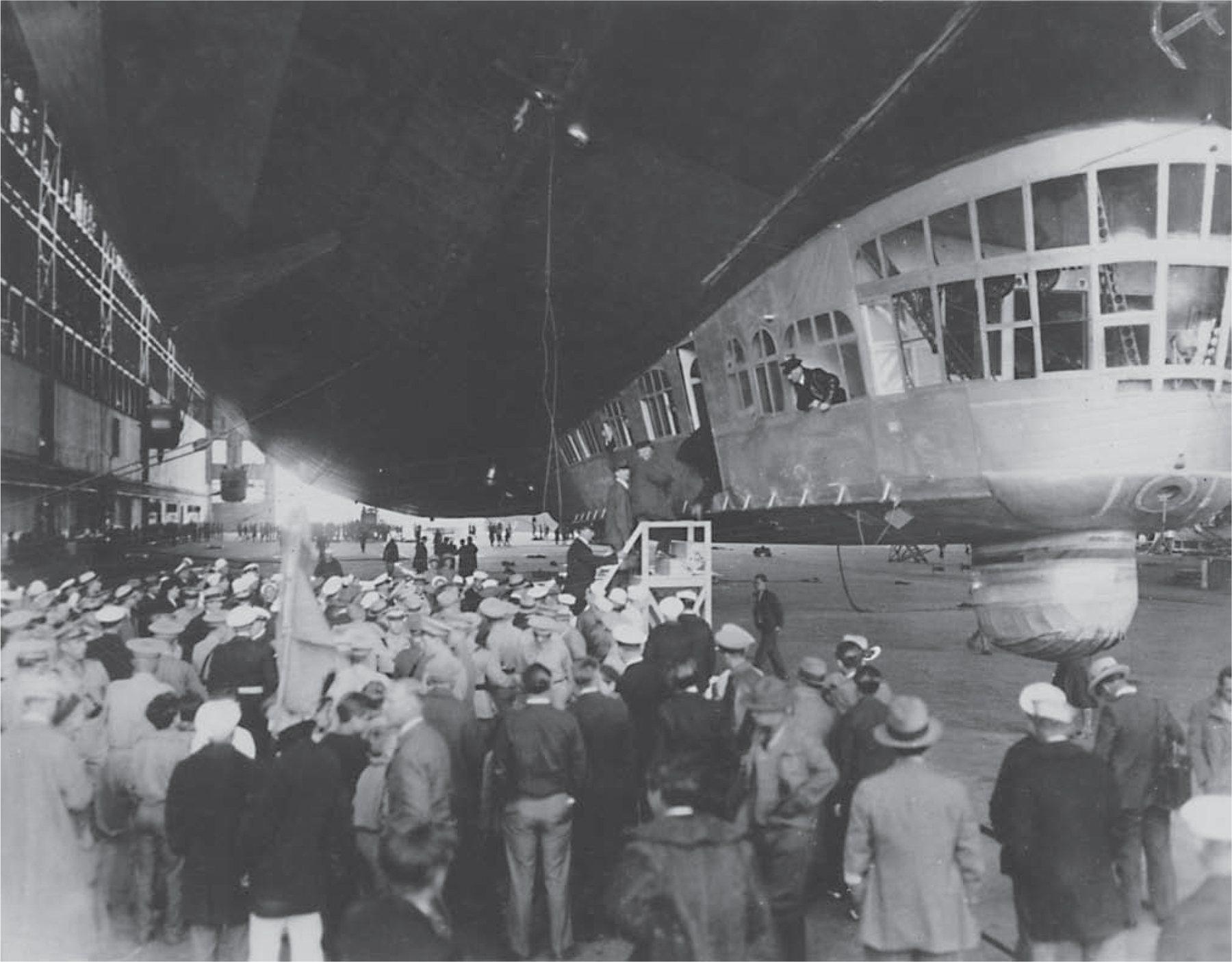

Gripped by the rail mast, stern beam, and handlers, LZ-129 is shunted under roof. Hindenburg would use the barn twice, her operators preferring their ship riding to a circle on the field. USN courtesy ADC J. A. Iannaccone, USN (Ret.)

By Wednesday, 13 May, helped along by the prevailing winds, Hindenburg was approaching the European continent. At midnight, 13–14 May, Hindenburg was thirty miles north of London, forty-four hours after leaving New York. The North Sea was crossed to Holland, thence to Frankfurt and the new Zeppelin terminal. The ship landed at 0541, 14 May, at the east end of the new hangar. Total elapsed time from Lakehurst: 48.5 hours.

Hindenburg’s first round-trip was a public relations triumph. As the season progressed the demand for tickets exceeded the available accommodations. Most important for the immediate future, American financial and political circles were following her progress with growing interest. And Hindenburg’s comforts and punctuality were having a very healthy effect upon public and naval opinion. Hindenburg’s 1936 arrivals and departures were printed in the New York Times steamship section—an indication that the American public had promptly accepted Hindenburg as a transoceanic transportation system.9

Germany had brought the passenger-carrying airship to the brink of public acceptance. Germany’s plans for the new year would have made 1937 the busiest in transatlantic history. A total of twenty crossings to South America were planned, while Hindenburg would depart Frankfurt for Lakehurst eighteen times. In all, the schedule called for seventy-six Zeppelin transits of the Atlantic between March and December.

Two additional elements heightened the prevailing optimism. A sister ship of Hindenburg would be launched in September, and a joint German-American consortium, formed that winter, would operate four airships for transatlantic service. The new sister ship, LZ-130, had been laid down in June 1936 at Friedrichshafen and was slated to make her maiden transatlantic flight to Rio de Janeiro on 27 October with about one hundred passengers.

Hindenburg being serviced with hydrogen, fuel oil (diesel), lubricating oil, provisions, and the discharge and embarking of fare-paying passengers and freight. On North Atlantic service—“Europe by Air in 2½ Days”—Lakehurst would log Hindenburg ten times during May–October 1936. Germany had mastered the problems of distance, navigation, weather, and public acceptance attending transoceanic air travel—or so it seemed. Mrs. C. M. Ruth

Close-up of LZ-129 on the landing field, NAS Lakehurst. Note the retractable stairway and lounge windows along the hull. K. Pace

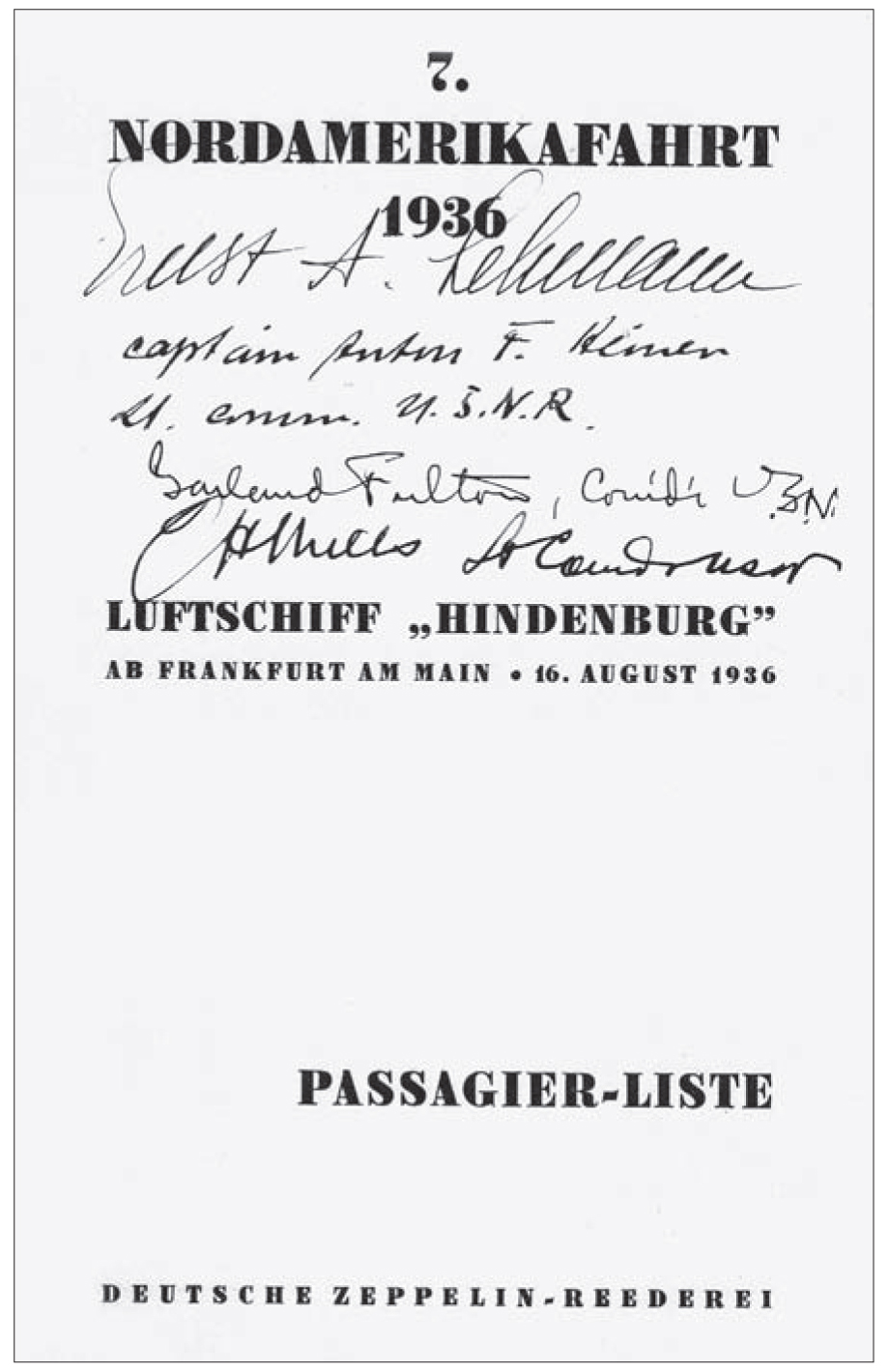

Passenger list insert for the seventh crossing via Hindenburg, August 1936. Signatures are those of Capt. Ernest Lehmann, in command, plus a trio of U.S. Navy officers taking passage as temporary duty to observe German practice. On return or arrival in Frankfurt, they were required to stow their Navy uniforms before disembarking. Mrs. Elsie C. Harwood

World’s largest airship walked to the mast. Hindenburg announced scheduled transoceanic air travel. For both airplane and airship, a practicable service depended in part on accurate weather information. Here the venerable L.A. is moored out for tests. Wide World courtesy Navy Lakehurst Historical Society

Eyewitnesses, NAS Lakehurst, 6 May 1937. The two at left are unidentified; the woman is Jean Rosendahl, wife of the station CO. The assistant ground-handling officer directly below Hindenburg recalled being “somewhat doubled up” by the downward force of the explosion. “It was not a night of rest for anyone.” C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

The 1937 transatlantic season opened with a round-trip crossing by Hindenburg to Rio between 16 and 27 March, followed in April by Graf Zeppelin. After a three-day turnaround, the older ship again departed for the Brazilian capital on 27 April. On 3 May Hindenburg lifted off the Frankfurt airfield for Lakehurst on the first of eighteen scheduled visits to North America. Aboard the ship were thirty-six passengers and a crew of sixty-one, some of whom were under training for LZ-130. Delayed by persistent head winds, Hindenburg did not reach the Lakehurst area until late afternoon on the sixth, hours behind schedule.

Finally, at 1900, an immediate landing was recommended. The first line thumped to earth at 1921 and the high mooring operation began. The air station log matter-of-factly records the events that began four minutes later:

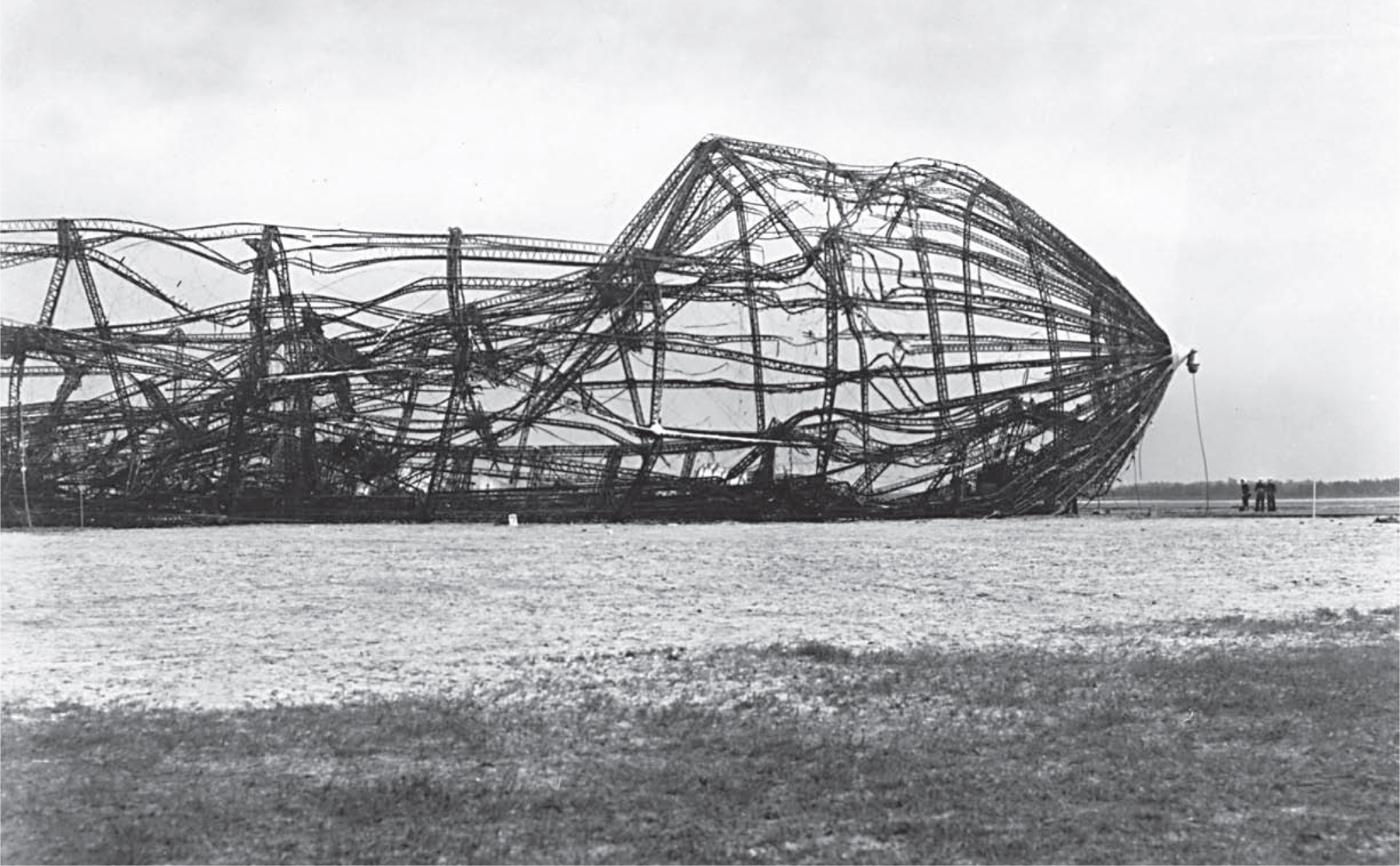

During the landing operation, the Airship Hindenburg burst into flame at an altitude of about 200 feet and was burned to destruction by hydrogen fire originating at or near the stern. The ship fell to the ground on the north side of number one mooring out circle approximately 232 yards from the mooring mast. Out of ninety-seven persons aboard about twelve passengers are known to be saved and thirty-seven of the crew are alive, some injured to various degrees. . . . The fire in the wreck was put out as soon as possible by the Naval Air Station and several nearby city fire departments. Rescue work was commenced immediately, ambulances and doctors from several nearby hospitals answering the call for first aid assistance. Sentry posts were established and manned to keep all visitors and unauthorized persons clear of the Hindenburg wreckage.10

Thirty-six lost their lives: thirteen passengers, twenty-two crewmen, and one civilian member of the ground crew. Germany’s perfect record of safety had been shattered in a spectacular tragedy before the assembled media and public. The commercial airship would never recover.

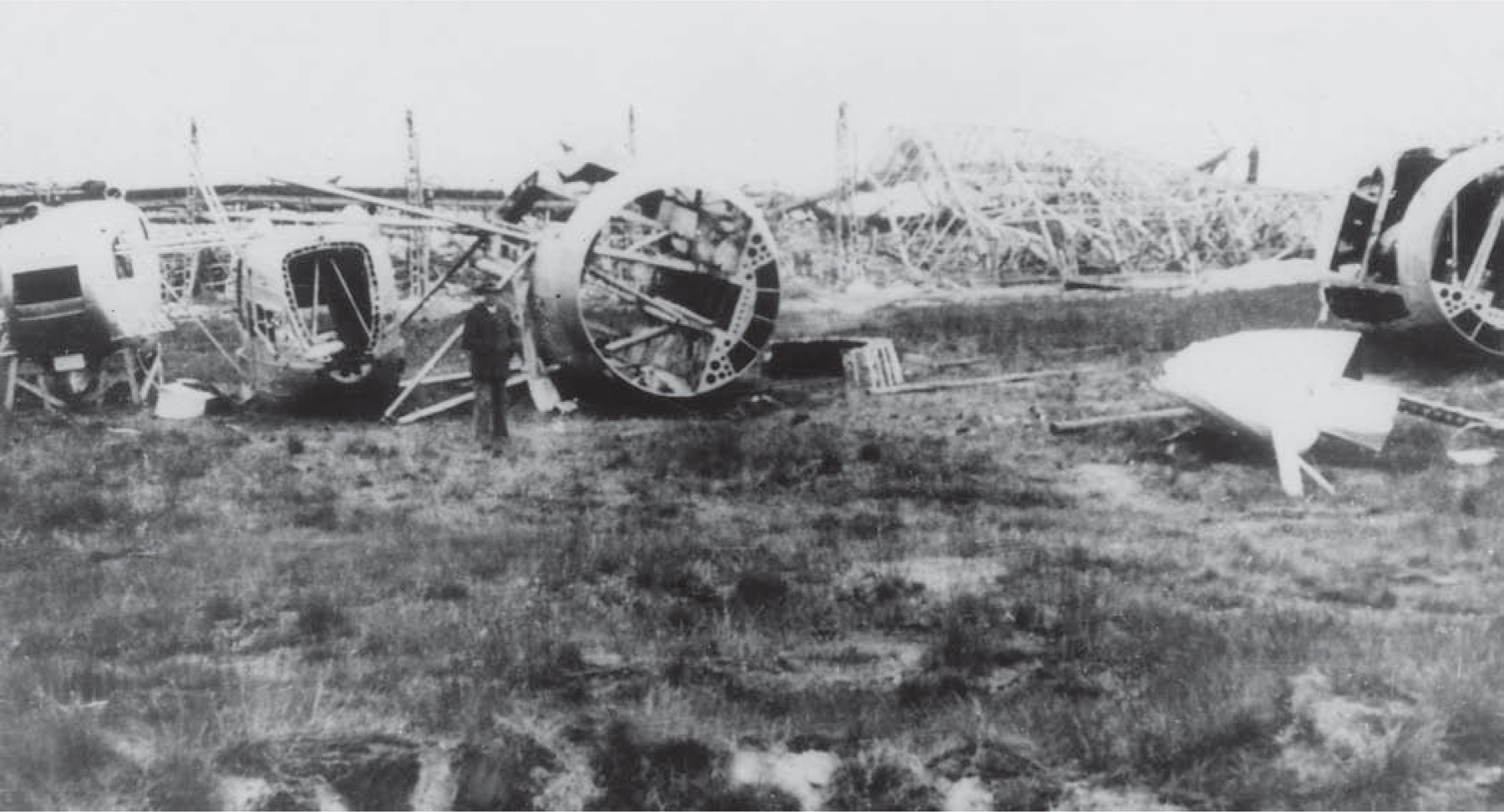

Skeleton of Hindenburg and a watch set over the wreck. A “quiet of disbelief” descended on NAS Lakehurst. Commercial hopes rested now on Germany’s access to U.S. helium. The domestic airlines—still small—had their own transoceanic plans; the DC-3 was flying, service by Pan American “Clipper” an operational fact. Given the unsettled international politics of the late 1930s and lobbying by airline interests, the commercial airship was finished. NARA

The facts remain inconclusive, and the cause is much debated. Yet there are only two plausible explanations for the Hindenburg’s end: accident or sabotage. The theory of sabotage, a sensitive matter in 1937, has been the source of endless speculation and has provided interesting (and saleable) drama. Even experienced airshipmen came to believe this interpretation. Yet no conclusive evidence of sabotage was ever uncovered.

There is ample evidence, however, that the ship was tail-heavy during the fateful landing—suggesting a hydrogen leak aft. Special Representative F. W. von Meister, an eyewitness, noted that water ballast was dropped aft three times during the approach, an action he considered unusual. A “rosy glow” was noticed by at least one Navy enlisted man immediately before a flame appeared. Others on the ground noted a flutter in the outer cover aft. Moreover, several crewmen were in the tail near the origin of the fire yet survived the crash. One, the chief engineer, happened to be looking up the ventilation shaft between cell nos. 4 and 5 when he saw a flash blossom from the top downward toward him.11 It was the flame from this ignition that appeared atop the hull and signaled the end to those on the ground.

It is probable that, for whatever reason, a mixture of air and hydrogen was present and, for the first time in the history of German commercial operations, was somehow ignited by a static discharge. One fact is indisputable: the fire could not have occurred if Hindenburg had been helium inflated.

Hydrogen would never again be used to carry passengers. The future of the transoceanic airship rested now on the availability of American helium—and that vital helium was not forthcoming. Without it, the commercial transoceanic airship was finished. On 14 September 1938, LZ-130, the most modern rigid airship ever designed, made her first flight and was christened Graf Zeppelin. She never carried a paying passenger. Europe was soon at war, and the large airship shunted aside—an aerial anachronism in a preoccupied world. War declared, the newest ship was immediately grounded, joining the veteran LZ-127—retired since June 1937—in a Frankfurt hangar. Considered to have no military value, in March 1940 both Graf Zeppelins were unceremoniously dismantled by the Nazi government and the Frankfurt hangars destroyed.

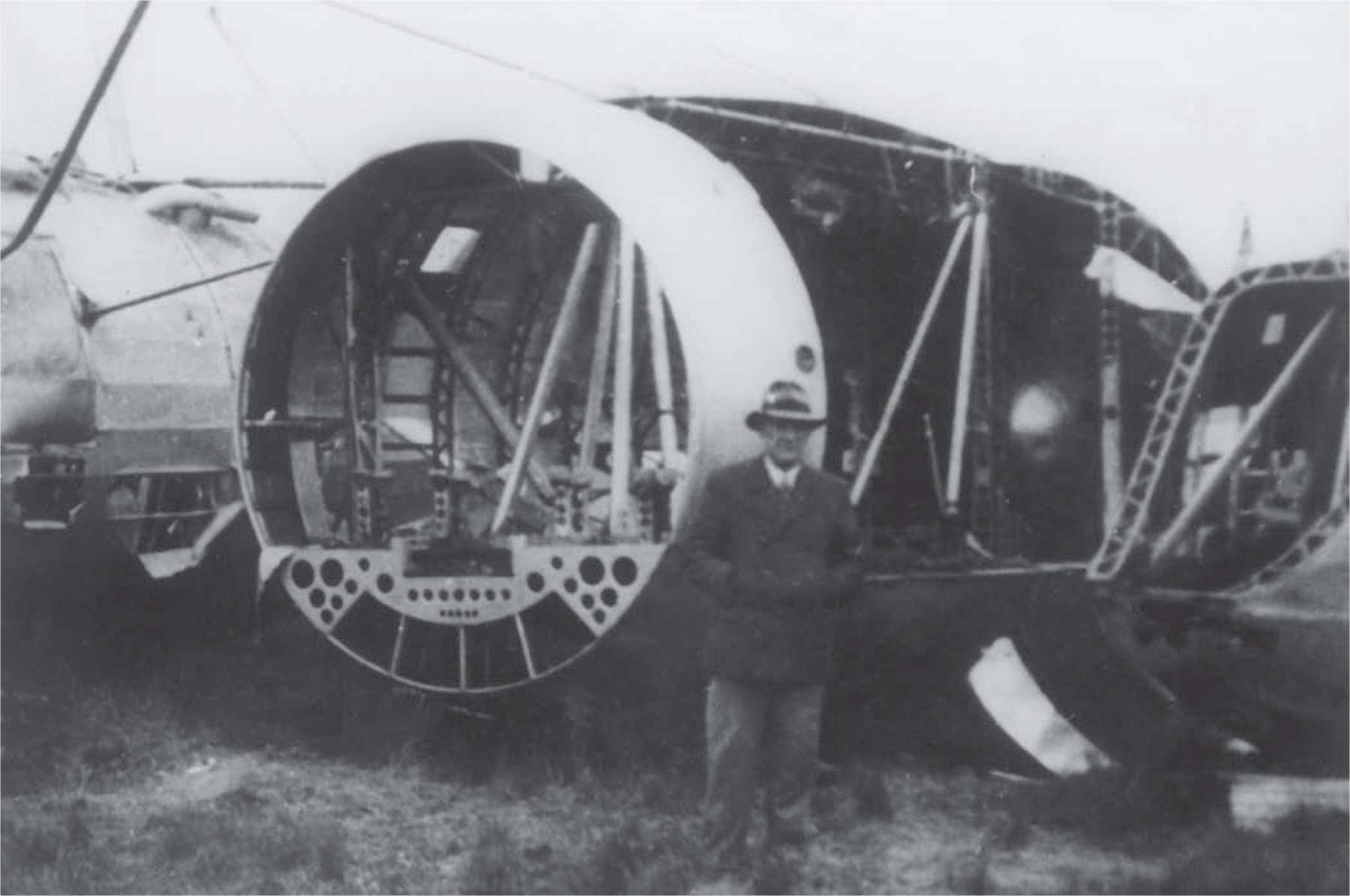

Power cars from LZ-130 and LZ-127 at Frank-am-Main, March–April 1940. As late as February 1938 Berlin still planned to resume transatlantic service with LZ-130, assuming sale of U.S. helium. The Air Ministry had ordered the dismantling. The figure is Anton Wittemann, one of Hugo Eckener’s cadre of Zeppelin commanders. The world at war, there would be few eulogies. Friedrich Moch courtesy D. H. Robinson