Japan had delivered a staggering blow. The American military and its industrial plant were unprepared for the profound demands now set before them. A fearful year lay ahead, months of furious reactions, intense preparations—and the first defeats on land and at sea. Slowly but inexorably, like a sleeping giant rudely disturbed, the new combined might of the Allies would turn the war against the Axis. The Battle of the Atlantic in the first half of 1942 raged with unremitting fury, but now American naval forces were formally and fully committed.

On 11 December, Germany declared war on the United States. Restrictions against attacks on American shipping along the Eastern Seaboard, an area closed to U-boats under Hitler’s order, were now removed. Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of all German undersea forces, orchestrated an early assault, which struck quickly and hard. The trade war against the Americans commenced on 15 January.

The overextended coastal defenses were fully exploited by Dönitz’s boats. In only two weeks fourteen Allied merchantmen—including nine tankers—were sunk by the first wave of five U-boats operating near the American East Coast. And this was but the beginning of a very grim six months for the defenders. Between January 1942 and that August, when a trans-coastal convoy system was initiated, 360 merchantmen were sunk, representing about 2.5 million gross tons. Countering, only eight U-boats were destroyed. These losses shook American confidence and alarmed Britain, an ally whose war effort depended utterly on a reliable stockpile of matériel and food. The flow of oil from the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies to Allied military operations in Europe and in the Far East was soon threatened.1

Washington’s defenses were thoroughly overwhelmed. President Roosevelt wrote ruefully to Prime Minister Churchill in March 1942, “My Navy has been definitely slack in preparing for this submarine war off our coast.”2 Air and sea patrols at this time were few and completely inexperienced. The merchant marine was equally unprepared. Single-ship traffic, for example, was far too plentiful for marauding submarines and the targets clumsily handled against possible attack. Merchantmen steamed fully lit and transmitted routing information in plain English over frequencies regularly monitored by the U-boats. A coastal blackout had yet to be imposed. The lights of seaside cities and resorts created a glow that silhouetted the hapless targets. A pleased and surprised Admiral Dönitz noted that conditions off the American East Coast were “almost of peacetime standards” and that “the American fliers see nothing.”3 Further waves of undersea raiders were therefore dispatched to take full advantage of conditions prevailing in U.S. waters and as far south as the Gulf and Caribbean.

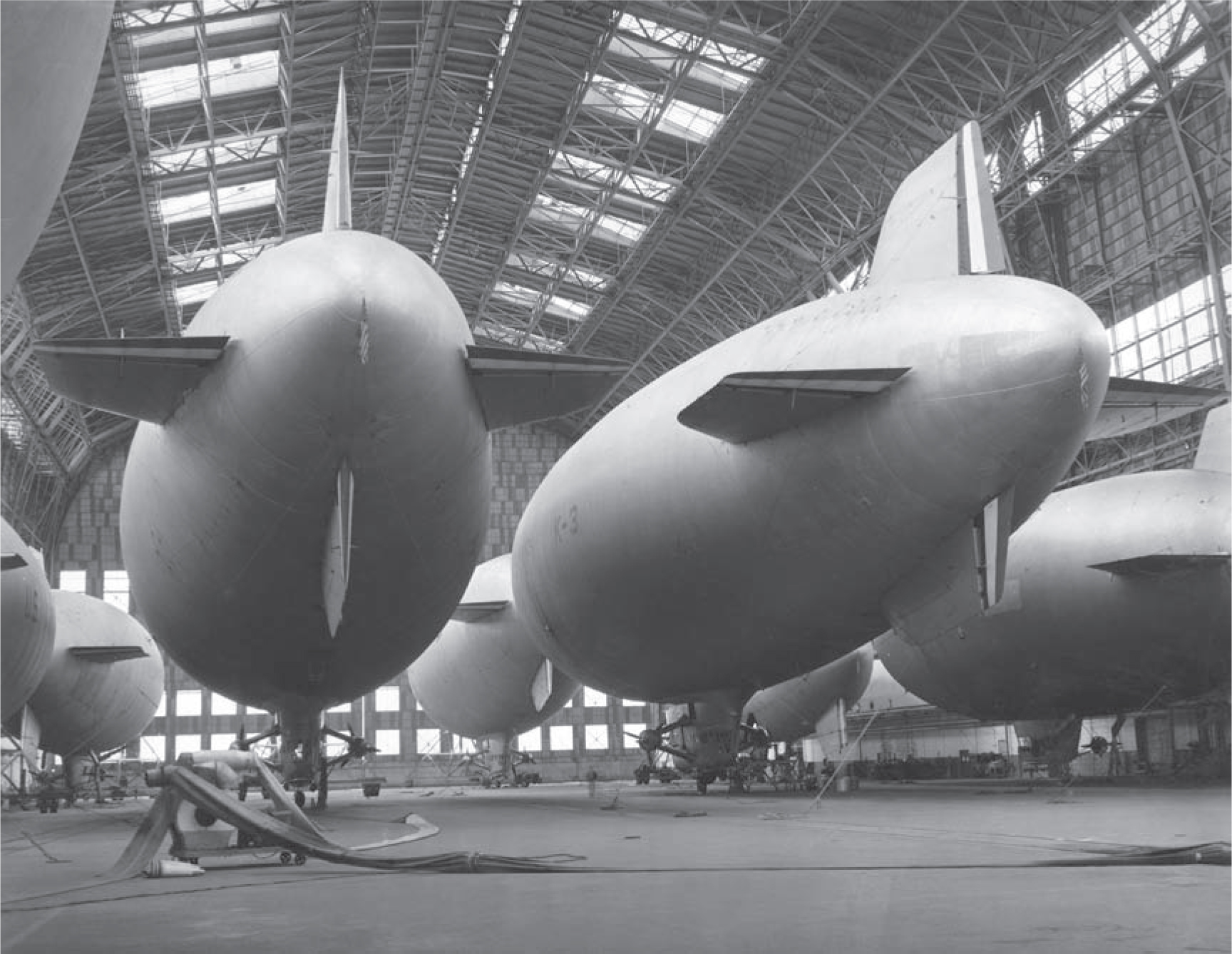

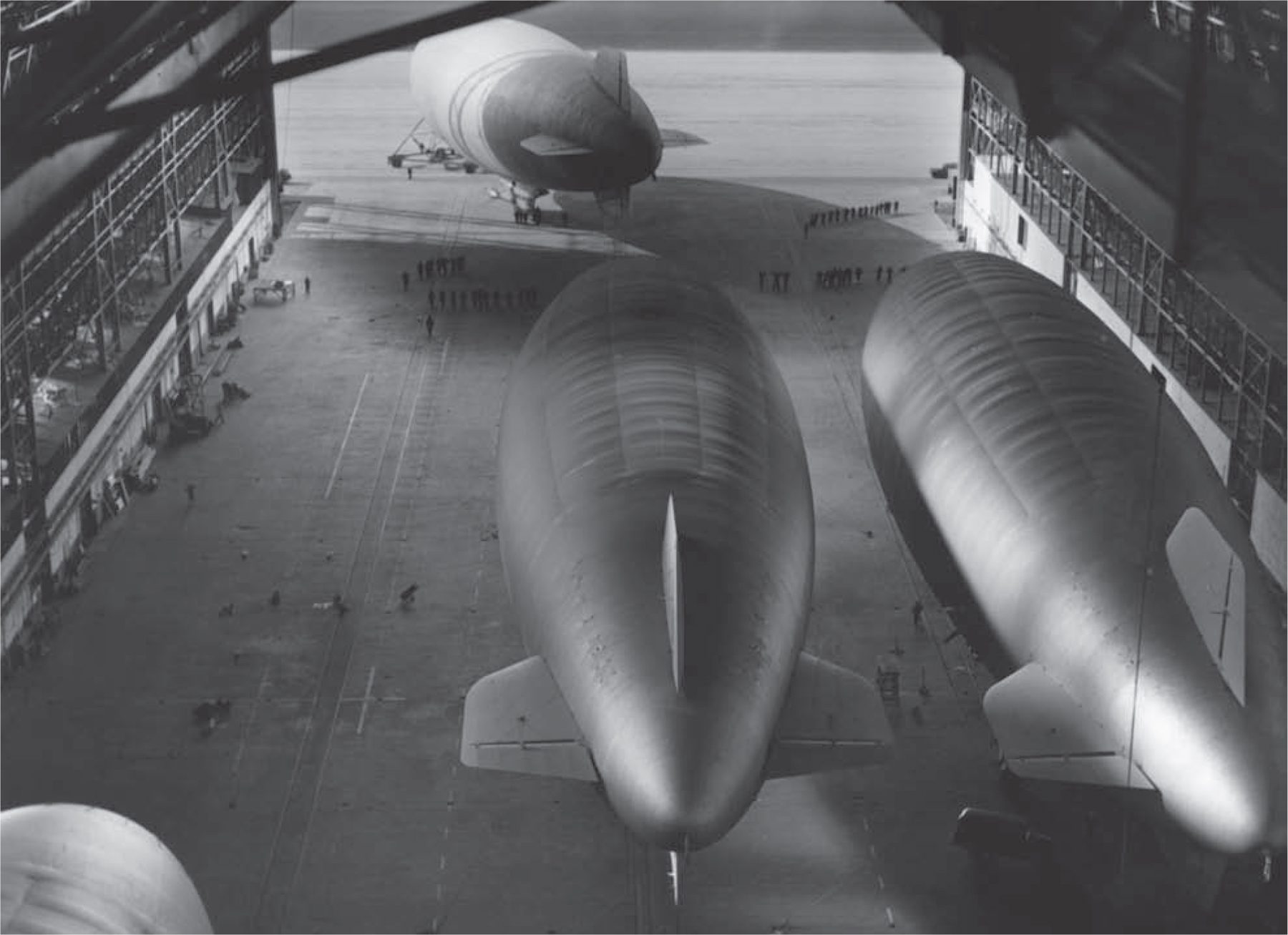

K-2, 16 December 1941. Upon word of Japanese attack, armed watches had been posted, the guard doubled, and “all possible precautions” taken to prevent sabotage. Hangar No. 2 was under construction, one element of a station-wide expansion to help meet the national emergency. Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

Navy lighter-than-air was pressed into the antisubmarine campaign. In this first winter of the American war, NAS Lakehurst remained the sole LTA base operational on the whole of the continental United States. The station was alive with frantic activity. Immediate plans focused on the additional shore facilities needed to support the forty-eight-ship fleet already authorized. Blimp squadrons had to be formed, new bases commissioned to support them, personnel trained, and the aircraft delivered and equipped.

Airship Squadron Twelve (ZP-12) made its inaugural flight on 3 January 1942. Patrol airships K-4 and K-5 were to escort a thirteen-ship convoy, including its lone surface escort, during daylight through the coastal area off New Jersey from Barnegat Lightship south to Five Fathom Bank Lightship. Southbound, standard escort procedure was to accompany a convoy a few hundred miles until the blimp was detached. The blimp then landed at the Elizabeth City naval air station in North Carolina (as yet unfinished). A northbound convoy was then escorted on the return leg to Lakehurst. For its part, Elizabeth City supported LTA patrol and escort coverage for the Cape Hatteras and Hampton Roads sector. Thus, as new stations were commissioned in the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coastal frontiers, an overlapping aerial coverage became possible for the length of these coastlines. But full air coverage remained unavailable until 1943.

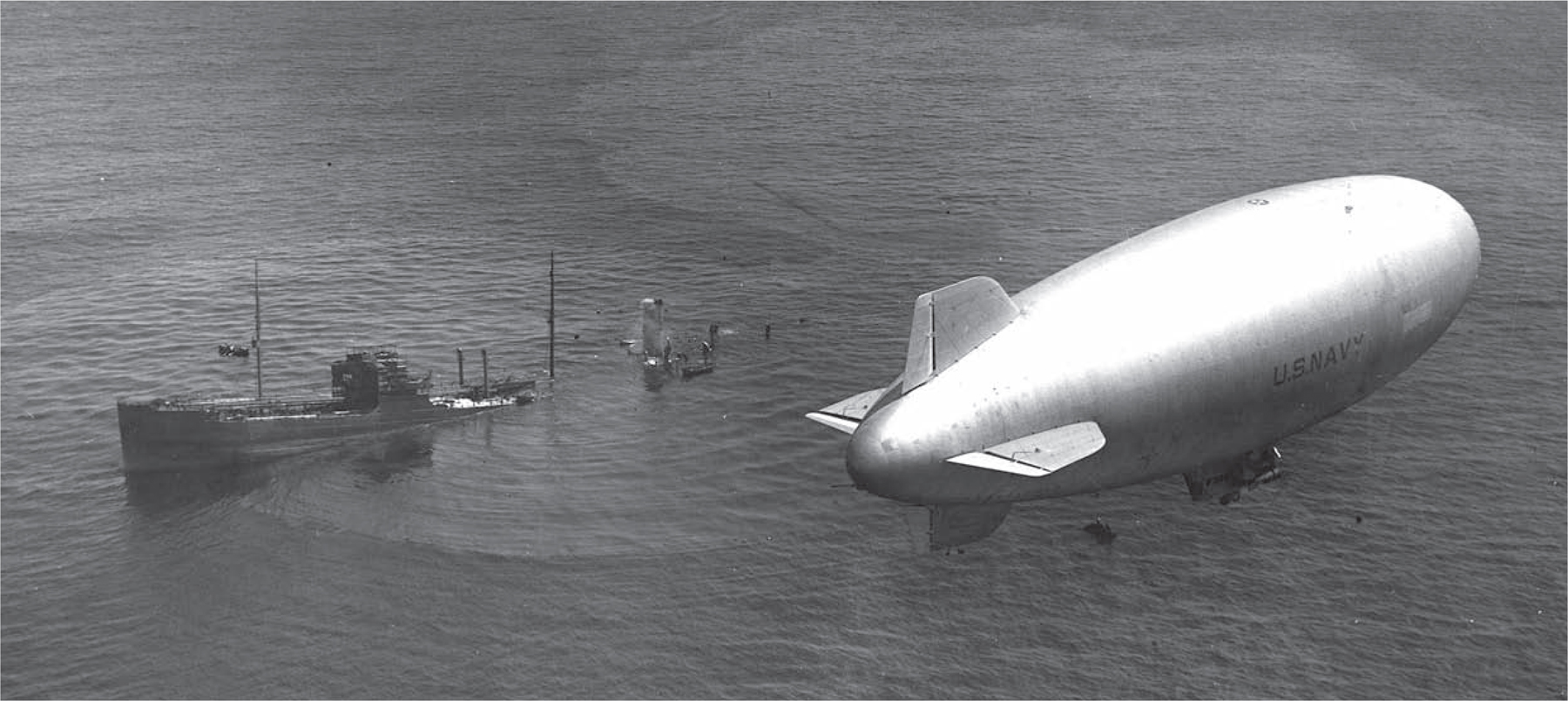

K-2 in company with ex-Army TC-13 and TC-14, a tiny force to help defend the inner sea lanes of the trade war. The image is emblematic: a prototype, hand-me-downs, and tactics ill-prepared for antisubmarine warfare. NASM, Smithsonian

NAS Lakehurst, 2 March 1942. By CNO directive, Airship Squadron Twelve (ZP-12) was commissioned on 2 January—a first for the U.S. Navy. The assignment was patrol-escort off New Jersey and the port of New York, the best natural deepwater harbor on the Atlantic Coast. Operational control: Commander, Eastern Sea Frontier, headquartered in lower Manhattan. Capt. J. C. Kane, USN (Ret.)

Escort missions were but one of many assigned. Submarine searches and patrols, rescue work, assistance in torpedo recovery and, somewhat later, calibration of direction-finding equipment on surface ships also were assigned by the Sea Frontier commander. But as the 1942 U-boat offensive intensified, missions consisted principally of submarine searches and development of U-boat contacts logged by blimp or by surface forces. The harassed Sea Frontier commanders required all possible naval air support. As the year progressed, these terribly engaged officers were among the airship’s biggest boosters. The demand for LTA-related services rose considerably.4

To seaward, the enemy was present in force. The first LTA rescue of the war was logged on 15 January, the opening day of the U-boat offensive against the Americans. The victim, the Norwegian Noress, was among the very first merchantmen to be torpedoed. The blimp K-3 was on ASW patrol near Nantucket Lightship where the presence of an enemy submarine was suspected. Shortly after dawn, the blimp was approached by an airplane that circled and then headed off. K-3 altered course and followed. Soon the lookout forward sighted an object ahead, which, upon approach, was found to be the bow of a ship. It was Noress; her stern was resting on the bottom. A search for survivors was begun immediately; a few miles from the wreck a raft with four men was sighted. The airship was headed into the wind and flown low over the raft where, with difficulty, an awkward communication was established by megaphone. Lakehurst was radioed and orders received to remain with the raft until surface assistance could arrive. In the meantime, hot soup, coffee, and sandwiches along with cigarettes and matches were lowered. A further search of the area yielded an overturned lifeboat but no additional survivors. Finally, at 1600, a ship arrived and the men taken aboard. K-3 continued the search with negative results until 1730, when the blimp returned to base.5

ZP-12 made its first sighting of the enemy on 16 January. On patrol, the K-6 sighted a surfaced submarine three thousand yards distant in the immediate vicinity of Barnegat Lightship. Battle stations were manned, and the blimp attacked at full speed. The target crash-dived, submerging completely in thirty seconds. One depth charge was dropped, but no traces of oil or debris were seen. The area was searched without further incident. Shipping was warned of the U-boat’s presence, and “King”-6 returned to Lakehurst. K-3 was ordered to the scene to locate the submarine with her new, highly classified Mark I magnetic airborne detector or MAD.

Merchant shipping is the heart of international trade and, in global war, overseas supply of strategic materials. One must appreciate the genuine urgency of war at sea, the year 1942 particularly grim: sea control contested in all Atlantic sectors and antisubmarine defenses overwhelmed. Here K-4 circles SS Persephone, 25 May. Inbound for New York, the tanker had taken two “fish” from U-593, likely making it the only vessel torpedoed while under LTA escort in two world wars. USN

The development of MAD—and airborne radar—during 1940–44 is a fascinating story in itself and one that underscores the tightening embrace between science and the business of war. When the European conflict began, optical methods alone were available for the detection of surfaced submarines. No means whatever existed for detecting submerged submarines from aircraft. Research on magnetic airborne detectors had begun late in 1940 for application to geophysical prospecting. But early in 1941 the newly created National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) assumed sponsorship of MAD development. Some of the early research was done at NAS Lakehurst by civilian scientists. In October 1941, successful tests were carried out in cooperation with the NDRC, conducted from a Navy PBY assigned to NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Not until the spring 1942, however, were the first satisfactory MAD sets, designated Mark II, delivered to Lakehurst for trials. The results were promising. Improved models were used in most operational theaters with varying degrees of success for the balance of the war.6 Coincidentally, the first microwave radars for surface search from aircraft also were being installed at this time. The Navy’s prewar development program had begun in October 1940. Again, the NDRC was the organizational sponsor. By summer 1941 ship-based and airborne radar were beginning to transform naval warfare.

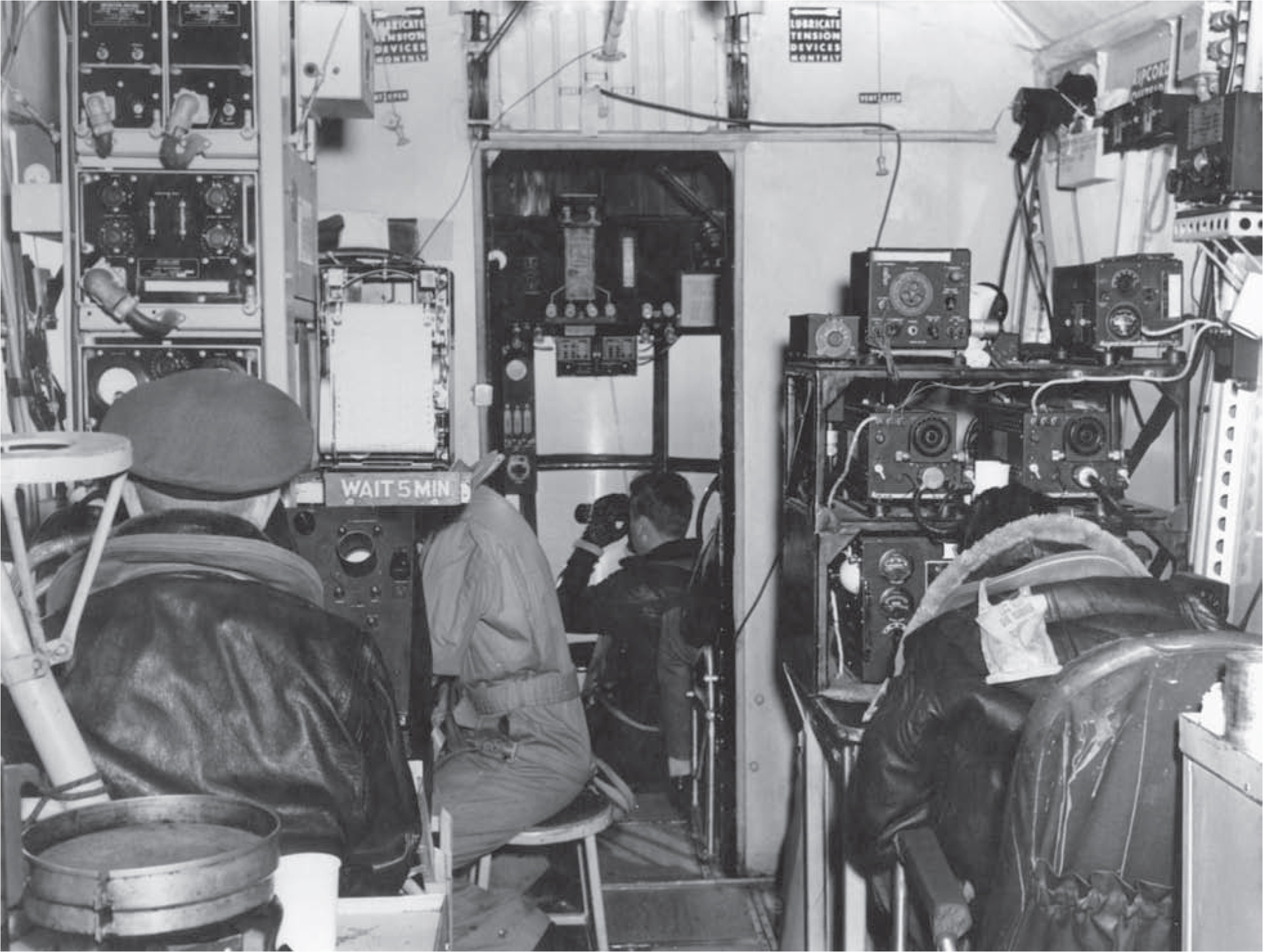

Lookout in the bombardier’s seat—in a “well” fitted with the releases. Combat aircrews (CACs) were granted a superb field of view, no obstructing wings. The advantage of low-speed search was pronounced, though blimps could not attack as fast as patrol planes. The radar MAD operator is nearest the camera portside, the navigator forward. The radioman is seated to starboard. At left, the recording chart for the magnetic airborne detector (MAD). George H. Mills Collection, NASM, Smithsonian

Lookout aft scans the sea while shipmates rest between watches. The mechanic (right) is monitoring his instruments. The command pilot saw to it that both mech and radioman also were lookouts. George H. Mills Collection, NASM, Smithsonian

Unfortunately for K-3, the MAD power supply failed on her 16 January patrol and her radar was operating poorly. No magnetic contacts were made on the sixteenth. The next day, a MAD contact was made by the airship, tracked, and then lost. Further search that night realized no further contact with the enemy.

A busy K-3 departed Lakehurst again at 0617, 18 January 1942, on convoy coverage and ASW patrol. Just before rendezvous, a MAD contact was logged. Immediately after, a submarine began to surface, then crash dived. The target was trailed and attacked without success, thanks in part to a depth charge that failed to explode—the first dud reported for the squadron. It was to be the first of many. Two bombs were dropped on a second contact that afternoon near Ambrose Lightship off New York City, one a dud, but no evidence of damage was observed.

Four days later, K-5 on routine ASW patrol observed two submarines emerging in the center of a turbulence of foaming water. After perhaps ten seconds both crash dived. The K-ship raced to the spot, where three depth bombs were released in succession from six hundred feet, but again, no definite evidence of wreckage appeared after the attack. The remaining bomb was dropped on suspicious bubbles, then the area was cleared for an Army bomber, which also attacked with no apparent damage inflicted. K-3 arrived on the scene to continue the hunt while K-5 set a course for home.

The fleet squadron based at Lakehurst remained the only LTA unit in the conflict until midyear. But in June, ZP-11 and ZP-14 were commissioned and based at NAS South Weymouth and NAS Weeksville, respectively. On 2 July 1942, ZP-12 completed its first six months of wartime operations with eight aircraft, K-3 through K-10. The four original ships had flown 5,393 hours, or an average monthly flying time of nearly 225 hours per aircraft. Operational demands would continue to intensify. The squadron flew another 134 flights that July alone, for a total of 1,747 hours aloft. The squadron was in the air each day of the month, nearly all flights logged over water. Only one casualty was sustained, when K-6 deflated at the mast during a severe thunderstorm at South Weymouth. No lives were lost.

At sea off the New Jersey coast and along the Eastern Seaboard, grim evidence of the escalating battle was becoming altogether too evident. The masts and smokestacks of torpedoed ships were multiplying alarmingly. Sightings of wreckage, oil slicks, and bodies increased. Along the resort beaches, grisly reminders of the war at sea were washing ashore.

U.S. aerial and surface forces were throwing all their limited resources into the struggle. But the aircrews sent to sea in these first months, both HTA and LTA, were unable to mount a truly effective retaliation. The lighter-than-air program was late in receiving the specialized equipment, intensive training, and research attention so crucial to a successful response. The naval nonrigid had become virtually nonexistent after the First World War. Now, in this new crisis, antisubmarine tactics had to be relearned, then honed through hours of practice aloft. Circumstances dictated that this vital experience be acquired during the battle.

Its design virtues notwithstanding, the K-type patrol ship fell short from an engineering and operational viewpoint. The nonrigid had received erratic development attention in the 1920s and 1930s. Now a full-scale production program was under way. K-1 had flown for the first time in 1931, ten years before Pearl Harbor. But testing and design improvements had been painfully slow. K-2, the true prototype for the K-series, did not fly until December 1938. As one result, refinements in the basic vehicle had yet to reach the drawing board, let alone be incorporated into standard production models at the factory.

Similar delays attended LTA-related equipment and ordnance. A depth bomb suitable for the airship platform did not reach production until 1944. In the interval, the program had to adapt and improvise. In these first frantic months all patrol ships were not yet equipped with MAD and radar. Moreover, the MAD gear tended to operate erratically when it operated at all. And the lack of training compounded all shortages and deficiencies. Inevitably, inexperience under pressure exacted its penalty. An overwhelming majority of the losses and major casualties suffered by lighter-than-air during 1941–45 were traced to personnel error.

Early in the war particularly, flight crews were unable to exploit the then-available equipment. The MAD gear is a primary example. Magnetic anomalies from submerged submarines could be detected reliably only by flying relatively close to the water—within about two hundred feet. Thus, the slow, low-flying blimp was an ideal aerial platform for MAD. But the majority of pilots were generally unaware of this low-altitude limitation. Flying near to the surface, moreover, demanded fine airmanship and was physically taxing, even for short intervals let alone an eight-hour patrol. Consequently, the first patrol ships were fortunate to obtain a reliable magnetic contact but ill-prepared to interpret the signals they did receive. Standardized tactics to track and then attack a submarine using MAD were unavailable in 1942. False contacts often were bombed, and genuine targets, as with K-3, were lost. Many wrecks were depth charged since charts showing locations of known wrecks were not yet generally available. In sum, early in the antisubmarine campaign, when targets were most prevalent, lighter-than-air was learning on the job. As one inescapable consequence, the program’s overall effectiveness as a weapon system was below what it might have been, and its wartime record diminished thereby.

As the winter of 1941–42 faded into spring, the pace of construction at Lakehurst accelerated. Work was completed on Hangar No. 2, next to Hanger No. 1. The dock was placed in operation as the Assembly and Repair (A&R) Department hangar on 13 May. Hangar No. 3 was completed in late June for the training ships. And on 31 July, the Bureau of Yards and Docks, the Navy’s construction arm, authorized another two hangars, each capable of housing six patrol ships. Additions to the station’s crew’s barracks, a General Services Building, and a new fifty-unit housing complex for married enlisted personnel, among other projects, were either begun or completed this anxious spring and summer. The urgent demands of war were transforming the station. But now it was the blimp that defined Lakehurst’s contribution within the shoreside naval establishment. For the duration, the big ships were relegated to nostalgia. This same summer, the grass and scrub landing field west of Hangar No. 1 gave way to the need for a paved surface. Wartime payloads were requiring the patrol ships to take off heavy, taxiing on their wheel like an airplane, the engines lifting the extra weight dynamically. Thus, the old docking rails and mooring circles for Los Angeles, Akron, and Hindenburg were torn up and the landing field paved.

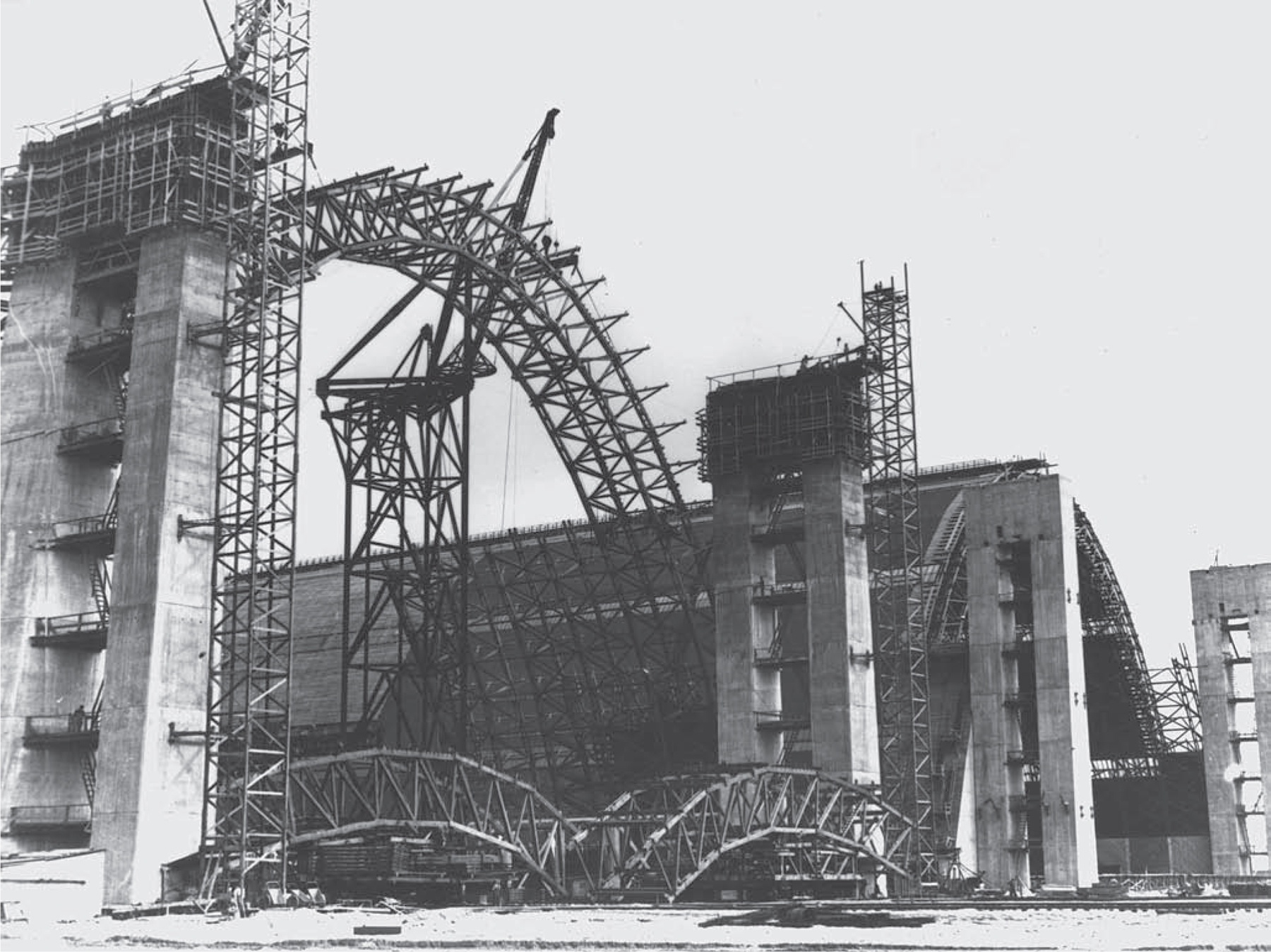

Hangars Nos. 5 and 6 under construction, April 1943. The concrete towers will support flat-leaf sliding doors that telescoped to each side. Coastal bases multiplying, standardized timber and concrete hangars were erected to support naval air stations authorized in Massachusetts, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Texas, California, and Oregon. Author

Paving Mat One under way, July 1942. The circle tracks have been cleared, though outlines remain. Sand and scrub is surrendering to a runway-like surface: airships lifting off heavy like a plane, the engines lifting combat payloads dynamically. Note the new and underway construction. NARA

Construction at South Weymouth and Weeksville moved toward completion. The original contract had called for facilities to support a single six-ship squadron: a steel hangar, helium storage and distribution lines, barracks for more than two hundred men, a power plant, a large landing mat and mobile mast. Both air stations were completed in the spring of 1942. Full support facilities were ready. Thus, on 1 June, ZP-14 was placed into commission at Weeksville, the second LTA squadron (or blimpron) of the war. The next day, at South Weymouth, ZP-11 was commissioned into the Navy.

The new squadron’s ASW capability at this moment was meager at best. Deliveries from Akron were still slow, and aircraft were to remain in chronically short supply for months. Three squadrons were now in commission to fight the enemy, but ZP-11 had no permanently assigned ships. Its only blimp, K-3, was on temporary loan from ZP-12. She made the squadron’s inaugural ASW patrol on 3 June. No airships would reach the Massachusetts unit until September, when, finally, K-11 was delivered. Airships continued to be assigned intermittently by the group commander at Lakehurst until October.

The forty-eight-ship program called for air stations on both the Pacific and Atlantic Coasts. Construction commenced on a new wartime base for LTA at Richmond, Florida, sited five miles inland and seventeen miles south of Miami. NAS Richmond was to become second only to Lakehurst as a primary overhaul base for airships assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. Its southern location, moreover, permitted operations within the Gulf Sea Frontier and within the sea area surrounding Panama as well, now increasingly threatened by U-boats. Work also began that spring on the first new West Coast station for LTA, near Los Angeles at Santa Ana, California. Both projects relied on the South Wey-mouth and Weeksville model, though shortages dictated changes. Wartime restrictions on steel necessitated substitution of a standardized timber and concrete hangar design, among the largest wood structures ever built. The fireproofed timber shells had a useful length of 1,000 feet and were 196 feet wide and 170 feet high at the centerline. Each contained more than 241,000 square feet of hangar floor. Ultimately, seventeen of these timber hangars were constructed during 1942–43 for lighter-than-air at coastal bases in Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Texas, California, and Oregon.

NAS Moffett Field. The station squadron, ZP-32, was commissioned on 31 January 1942. A fleet squadron comprised six patrol ships, though some units were assigned from four to as many as fifteen. Here a King, or K-ship is shunted into Hangar No. 1, authorized a decade before to berth Macon. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

A standard timber hangar, NAS Santa Ana, CA. The fireproofed shells had a useful length of 1,000 feet and a height of 170 feet at centerline. Note the blowers and inflation sleeves connected to ships’ ballonets to maintain envelope pressure. When docked, K-ships were trimmed 25 to 100 pounds heavy. The need to “fly” airships on the deck is one headache of LTA logistics. Cdr. C. A. Mills, USN (Ret.)

The Richmond air station was completed in the fall of 1942. Its squadron, ZP-21, was commissioned as a unit of the Atlantic Fleet on 1 November. Assigned aircraft: two K, or “King,” ships. The unit would operate within the Gulf Sea Frontier until December 1944, when a detachment from the squadron was established in Panama.

It is difficult now to appreciate the genuine urgency of the war at sea during 1940–42. During the first six months of 1942 especially, U-boat concentrations in U.S. coastal waters was very high. And 1942 would prove to be the most costly year of the war for shipping—454 sinkings in the Atlantic theater alone. A worried Prime Minister Churchill wrote to the American president that fall:

[The U-boat menace], I am sure, is our worst danger. It is horrible to me that we should be budgeting jointly for a balance of shipping on the basis of 700,000 tons a month loss. True, it is not as yet as bad as that. But the spectacle of all these splendid ships being built, sent to sea crammed with priceless food and munitions, and being sunk—three or four every day—torments me day and night.7

As part of the massive U.S. response, the LTA expansion plan was vastly enlarged. On 16 June 1942, the Seventy-seventh Congress authorized an increase in airship strength to two hundred aircraft. This same month, the Bureau recommended and the SecNav approved a 120-ship program. Also in June, a contract was awarded to the Goodyear Aircraft Corporation for a new prototype patrol airship, the M-1. The ship was to have an envelope volume of 625,000 cubic feet and a useful load in excess of 14,000 pounds.

The necessary planning for additional coastal bases was promptly realized, including the selection of sites and the letting of contracts. Construction commenced that summer. Stations were established inland from Galveston at Hitchcock, Texas, another at the Houma, Louisiana, Coast Guard base southwest of New Orleans, and at Glynco, Georgia. Seven stations—South Weymouth, Lakehurst, Weeksville, Glynco, Santa Ana, Moffett Field, and Tillamook (Oregon)—were enlarged by the addition of a second timber hangar each. And at Richmond, hangar space was increased to accommodate eighteen airships. Once these plans were approved, stateside construction initiatives slackened. Overseas bases were another matter. Authorization to establish LTA facilities outside the continental limits had been obtained in 1942. That December, the CinCUS directed that six patrol blimps (ZNPs) be operated in the Trinidad-Guiana area. The first squadron slated for duty overseas, ZP-51, was therefore commissioned at Lakehurst in February 1943 for transfer to the Caribbean Sea Frontier, with headquarters at Carlsen Field, Trinidad. Patrol operations (by K-17) began on 17 February 1943. Additional overseas bases, squadrons, and detachments would soon be established, notably along the Brazilian coast, and ASW patrol operations commenced over the South Atlantic.

The West Coast also was bracing for the submarine threat. With the declaration of war, attacks and sinkings by Japanese boats began. The SS Media was torpedoed and sunk off Eureka, California, less than two weeks after the Oahu attack. That February, a Japanese submarine shelled oil derricks at the Bankland Oil Refinery north of Santa Barbara.

On 7 December 1941, the U.S. Navy did not have a single airship on the whole Pacific Coast. But in April 1942, the Army finally vacated Moffett Field as per its 1940 agreement. Four Goodyear advertising L-ships were pressed into service. The Goodyear logo was replaced by “U.S. Navy” on the envelope, and, with minor modifications, the small ships became part of the Navy and began offshore patrols. That January, both TC-13 and TC-14 were deflated at Lakehurst and packed for rail shipment to California. Reassembled and reinflated, these two ex-Army blimps were the nucleus for the first West Coast LTA squadron of the war. But for this first winter, they remained the only LTA platforms assigned to the Pacific Fleet. Indeed, the Western Sea Frontier never had more than four airships on line in all of 1942.

The first West Coast LTA squadron, ZP-32, was commissioned at Moffett Field on 31 January 1942. TC-14 made the unit’s inaugural flight nine days later. Thirty-two flights were logged that February: twenty-seven for patrol and escort, three for training, and two experimental flights. By June, their number had tripled and hours in the air per month had roughly doubled. ZP-32 would make more than a thousand flights in 1942, totaling 6,410 hours.

The scale and pace of West Coast construction paralleled that along the Atlantic and Gulf. A building program was begun at Moffett to better adapt the station for ZNP operations. The station became the headquarters for the commander, fleet airships, Pacific, the main support facility for ZP-32, and the principal overhaul base for all Pacific Coast lighter-than-air craft. An Airship Training Center was established. Work also commenced that summer on an LTA station for the Pacific Northwest at a site west of Portland, at Tillamook, Oregon. Frequent fog and rain increased construction costs. And flying weather would prove far from ideal. Neither Santa Ana nor Tillamook contributed significant antisubmarine support in 1942. Operational experience was scarce, and night patrols were as yet too risky; only one night sortie was logged in all of 1942 along the entire West Coast. As well, evaluation of early contacts was slow in being standardized, as flight crews were new to ASW. The machinery for collecting information and intelligence, much less its evaluation, also was slow in being established.

An arduous year was ending. The twelve months since Pearl Harbor had witnessed horrific losses to submarines, a stumbling recovery by U.S. naval forces, and, in lighter-than-air, a frantic effort to equip, train, and deploy its few squadrons. Nonetheless, the wartime program had begun to assume specific outlines.

In December 1941 not a single fleet airship unit had been in commission. However, as 1943 opened, headquarters for a small but thriving Atlantic and Pacific Fleet organization had been created. NAS Lakehurst and NAS Moffett Field were homeports for one squadron each and, as well, serving as the main overhaul and fitting out bases for their respective coasts. New air stations and additional squadrons and detachments were either in commission or in planning. The Gulf operational command had one squadron assigned; another three would be commissioned. After one full year of wartime operations, the East Coast boasted three naval air stations in support of fleet airship activities. And three West Coast stations and their squadrons were operational—in sum, six antisubmarine squadrons in commission against the undersea threat.

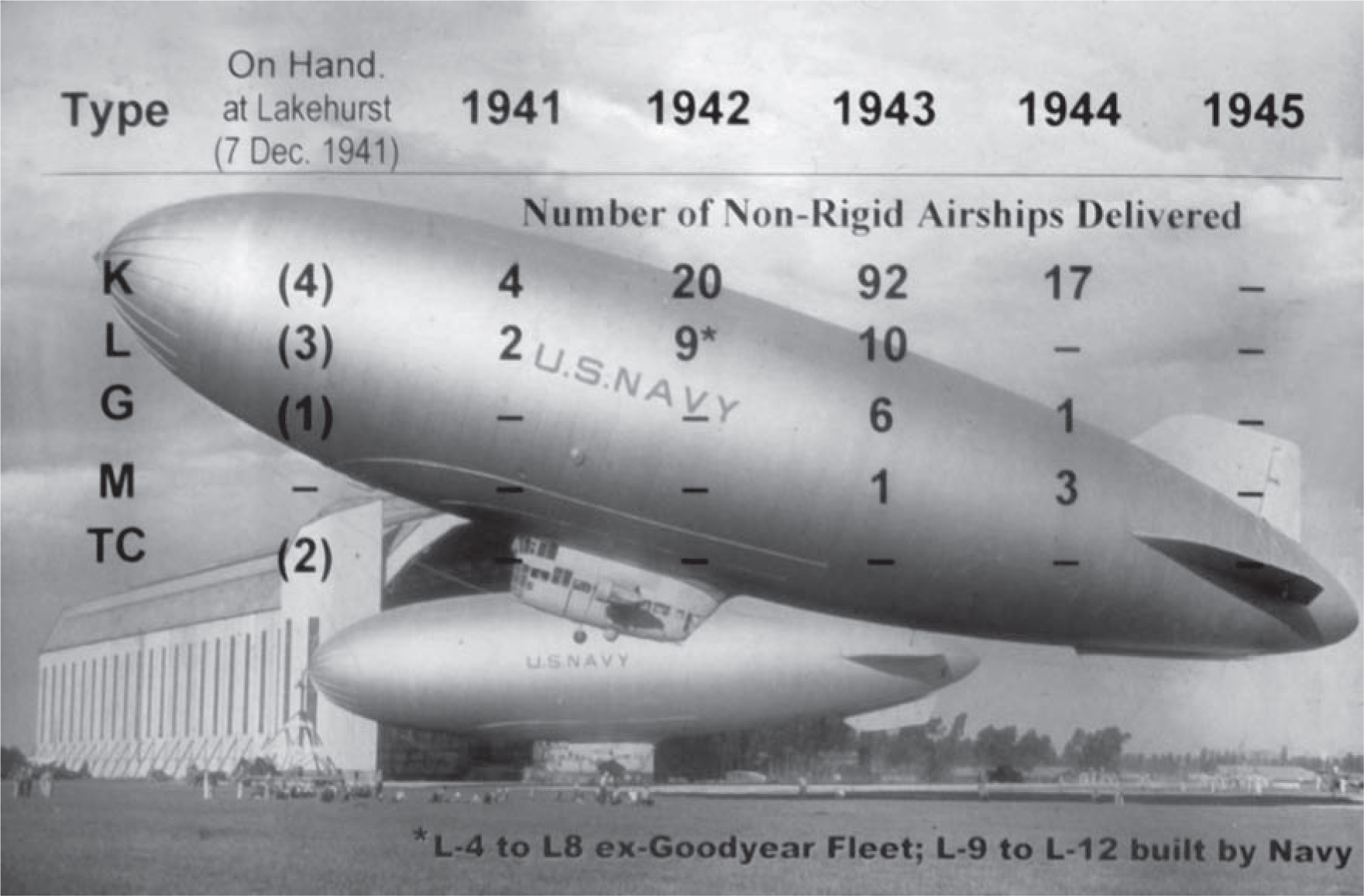

But the available aircraft were yet few. The Atlantic Fleet had only thirteen airships assigned; the Pacific, three. Another six were assigned to shore commands—a total of twenty-two aircraft on line. On 31 December 1942, the Navy had thirty-three airships in inventory: twenty-three K-types, the old TCs, and eight L-ships for training. In 1943 the number of K-ships in service would multiply nearly fivefold. Ten L-ships, seven of the new G-type, and the prototype M-1 also reached the operators. The LTA fleet was to increase nearly four times the number of aircraft on hand during the war’s first year. In 1942, Atlantic Fleet airships compiled more than twenty thousand hours in the air during 1,544 flights. Pacific squadrons logged nearly sixty-eight hundred hours. Atlantic units had flown a respectable two hundred fifty hours per airship per month.

Casualties were inevitable. Eight accidents had cost three aircraft and fifteen men in 1942. The first major accident had taken a dozen men. On the night of 8 June, Lakehurst’s L-1 and G-1 collided in midair during a research flight. Both crashed into the sea off Manasquan Inlet, killing four officers, three enlisted men, and five civilian scientists. That July, K-6 broke away from its mast. No lives were lost, but the ship was badly damaged and stricken from inventory. And that August, L-8 out of Moffett crash-landed without her two-man crew. The cause remains undetermined. On the ground, one crewman was killed in a handling accident.

The year 1943 proved to be a watershed in the war against the U-boat. That January, Roosevelt and Churchill met in Casablanca to discuss their future plans. A number of critical decisions were reached, among them an agreement that the campaign against the U-boat menace would have first priority. The shortage of shipping, aggravated by continued losses to submarines, was hampering all military operations. The Allies therefore proceeded to step up their ASW activities. From an increasing number of bases along the North and South Atlantic and from Britain, Iceland, the Azores, and the Caribbean, Allied aircraft and surface forces sought out the U-boat. The number destroyed now rose sharply. Heavy convoy losses persisted, but the overall situation in the western Atlantic improved. The grim total for Allied shipping had peaked, at 7.7 million tons. Sinkings along the East Coast dropped from its terrible high of 454 to 65 ships in 1943. The undersea enemy withdrew from the Eastern Sea Frontier into safer mid-ocean waters, away from patrolling ASW aircraft, now the U-boats’ greatest threat.

On word from the flight officer, the watch notified the ship’s rigger and mechanic to prepare for flight. Engines warmed, last-minute checks were run, gear and provisions put aboard, and the airship trimmed. With ground-handling personnel on the lines and car rails, the flight crew climbed aboard, and the ship turned over to the ground handling officer (GHO). Following weigh off, undocking commenced. Note the men grouped on the tail lines. When published in 1943, this image identified the NJ station only as a “coastal airship base.” NARA

Responsibility for the ship’s safety on the deck rested with the GHO until line release. Ops were flown by a CAC: command pilot, two copilots, and six or seven enlisted men as the basic crew. Armament: one Browning .50-caliber aircraft machine gun in the forward turret (early armament two .30-caliber) and four 325-pound depth bombs. The bombs were locked until over water, the gun loaded upon crossing the coast. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

The Battle of the Atlantic was far from won. But the prodigious scale of the Allied effort, as well as improved antisubmarine tactics, training, and equipment, mistakes by the enemy and myriad other factors had turned the battle against the Axis. The appalling drama at sea was to persist into 1945. Tens of thousands of sailors fought, and thousands of men died horribly amid the cold, unforgiving expanse of the vital Atlantic lifeline.

A wartime airship patrol was demanding duty for all hands. Preparations were exacting. By 1943, a familiar routine had developed. The flight crew reported for briefing and weather information and the latest intelligence summary. Included were the areas to be patrolled or the size and disposition of the convoy requiring escort. Points of rendezvous were studied and communication methods reviewed.

Ready Room, Blimp Squadron Eleven (ZP-11), NAS South Weymouth, MA, June 1944. Author

While the crew readied for flight, the hangar and ground handlers prepared the ship for departure. The K-ship and her engines were given preflight checks, and the aircraft was fueled, provisioned, and equipped for its mission. The envelope was topped off to give the desired lift. The ship’s armament was moved from the magazines into the hangar where it was carefully stowed on board: depth charges, machine guns and ammunition, Very pistol and star shells, smoke floats, and dye slicks. The predawn departure time approached quickly, and the black sky began to pale.

The blimp was trimmed for undocking. Her two Pratt and Whitney Wasp engines were warmed and the ship’s bow secured to a mobile mast. The ground crew manned the car rails and handling lines, and the flight crew was ordered on board after the command pilot had conducted his preflight check. A combat aircrew (CAC) consisted normally of the command pilot, copilot and navigator, and six or seven enlisted men: two mechs, two radiomen, and two riggers. Finally, with all preparations complete, the ship was weighed off, and, on signal, the mast began to roll toward the doors. Line handlers marched alongside as the ship was towed over the sill well out onto the apron. There the tail lines were cast off and the aircraft allowed to swing into the wind as the assembly was towed to the takeoff point.

When his ship was ready and cleared by the tower, the pilot gave the signal. The airship was cast off the mast, and the ground crew walked her astern as the mast was pulled aside. “Clear the car” was ordered, and the car party moved away.

The pilot advanced his throttles slowly to full power. It had become routine to take off about 10 percent heavy by taxiing down the mat like an airplane. Gradually, the aircraft accelerated. The pilot kept a slight “down elevator” during his roll to keep the bow from rising too abruptly and to allow the ship to build up air speed while holding her on the wheel. When the load was being carried dynamically the pilot eased back on the elevator, and the K-ship left the ground.

Flight crew at their stations ready for takeoff, the pilot signals. The mast is pulled aside, the ship’s lines released. The ZNP pilot held responsibilities comparable to those of a surface vessel commanding officer: operating at sea, he had to know wind, weather, and seagoing practices. Note the camouflaged water tank. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

When flying altitude—only a few hundred feet—was reached, the field was circled until the pilot was satisfied everything was in good working order. A course was then set out of the traffic control area. Life jackets were donned by all hands on approach to the coast. The bombs were kept locked until over the water, and the guns loaded only after crossing the beach. The lookouts went to their windows—but all aboard would act as lookouts in addition to their regular duties. All sightings were reported to the pilot.

Under way, the pilot was primarily concerned with maintaining a constant internal pressure. Envelope shape was maintained by the pressure of the helium and partly by internal air. The latter system consisted of two ballonets within the bag, one forward and one aft, along with the connecting lines, scoops on the engine outriggers, an auxiliary blower, and various valves and controls. A constant envelope pressure, especially during changes in altitude, was essential, not only to maintain shape but also to provide the best suspension for the car and operation of the controls. In normal straight flight, the ship usually was flown automatically, that is, pressure was maintained by a continuous circulation of air to and from the ballonets. Manual operation, or “pumping air,” was required in turbulent conditions and during severe maneuvering—such as attacking a submarine. “The real test of a nonrigid pilot’s skill is his ability to fly his ship in turbulent gusty air and still maintain altitude within reasonable limits and with a minimum of pitching.”8

The men settled in for a long patrol. Just aft of the pilot’s compartment were the spaces and equipment for navigation and radio. The mechanic’s station was farther aft in the center section of the forty-two-foot car, portside. His panel included all engine controls and instruments needed for operation of the power plants. Atop the panel cabinet a mechanical gong enabled the pilot to signal his mech, one of whom was always on duty monitoring the power system and reporting hourly fuel readings to the pilot. The on-duty mechanic also was responsible for shifting gasoline to the overhead tanks, which directly fed the engines.

K-car interior. View from the mechanic’s panel forward into the pilots’ compartment. The Rigger’s cabinet is at right, and, immediately forward, the radio operator’s chair. The radio table with its transmitters, receivers, and related gear is aft the partition to the pilots’ space. Portside, the galley area with its hinged shelf is nearest camera. Forward, portside is the navigator’s table with its instrument panel. NARA

Depending on its mission, a patrol blimp might operate close inshore or a few hundred miles out to sea. The objectives of patrol duty were explicit: to seek out enemy submarines, report their position, keep them under surveillance, and destroy them if the opportunity presented itself. Rarely however did the blimp operate alone. Instead, she might be assigned to join a “hunting” group—forces engaged in an ASW search—or to assist a “killer” group—air and surface forces in contact with and attacking a submarine. Most escort missions, in contrast, were within a hundred miles of the coast. Convoys usually held close inshore, along established sea-lanes and within easy air cover, individual ships shunting in or out of coastal ports until the assembled freighters and tankers along with their surface escorts turned seaward for another long and dangerous crossing.

The K-ship was an ideal surveillance platform. Large plastic windows nearly encircled the control car—providing superb visibility for search, with no obstructing wings. Lookouts were always at their stations and reported everything they saw: suspicious bubbles, unusual ripples, large oil patches, or the feathered spray of a periscope. Granted a measure of luck and unusual sea conditions, aerial observers might even see their quarry submerged.

A U.S. destroyer “somewhere in the Atlantic.” A year after Pearl Harbor, 200 airships stood authorized, with 120 contracted. U-boat attacks bred searches for survivors, dropping of emergency rations, and standing-by. LTA’s priority mission: escort of inshore convoys and antisubmarine patrol. The range of the early ZPK-type was about 1,900 miles at 40 knots. Wide World

Patrols were a ceaseless, exhausting vigil. Detection of submarines from aircraft is more demanding than it might appear. A host of factors affected the search: the color and depth of the water, the state of the sea, prevailing visibility and light conditions, and the wind. Together, these could combine to either hinder or enhance the hunt. A smooth or glassy sea, for example, allowed the wake of a periscope to be visible from three or four miles at one thousand feet under average conditions. But if the submarine slowed to bare steerageway, its wake practically disappeared. A choppy sea or reduced visibility owing to light, haze, or mist made it more difficult to sight and track the enemy. An experienced U-boat captain showed his periscope only briefly as he stalked. Thus, even the most intensive search might realize no sign of the enemy. One of the pilot’s decisions, therefore, was to select his search altitude to best meet the conditions prevailing in his sector. Crewmen aboard the U-boats, intended victims of this hunt, faced similar demands as they prowled for targets and greater dangers. A U-boat crewman wrote of his lookout duty in the stormy North Atlantic,

Four straight hours [on a bridge watch] of incessant vigilance—it can seem an eternity in any kind of bad weather. Every sea gull will turn into an attacking aircraft, every scrap of cloud rising above the horizon will look like a trail of smoke, the contours of distant waves will seem outlines of ships. . . . Some threat to the boat may lurk on every side, come hurtling out of every cloud.9

Sophisticated electronic “eyes” now augmented the airship’s visual search. Radar and MAD together helped master the U-boat threat. Evolving airship doctrine showed a trend to discredit oil slicks that produced no MAD contacts or other evidence substantiating a genuine contact, and to consider as routine the investigation of disappearing radar contacts. A disappearing or suspicious radar contact produced an immediate report to base as the blimp sped to the location, thereafter thoroughly developing the area with her MAD. On night patrol in 1944, for example, K-82 out of Lakehurst received a disappearing radar blip from seven miles away. The war diary for ZP-12 records the frequent inconclusive result of such contacts.

On patrol. Among the biggest boosters of LTA were the Sea Frontier commanders responsible for assembling convoys, coastal shipping, and coordinating the day-to-day requirements for naval air. Air ops were controlled from the operational office of each Sea Frontier, for Lakehurst, the New York office of the Fourth Naval District. USN

While the airship was proceeding on a course toward the blip, the contact was lost at 5 miles after being held on the scope about two minutes. The contact was strong and clear and the airship made a search of the area for three hours before it resumed patrol; no more contacts were received.10

The K-type nonrigid was a superb visual and electronic ASW platform. A long-endurance vehicle, the K-ship, as modified toward war’s end, possessed a fifty-nine-hour cruising endurance granting a range of 1,460 miles. This capability permitted a methodical search of large sea areas and, if necessary, allowed the ship to remain on the scene until the likelihood of detecting the enemy was exhausted. In contrast to the speeding patrol plane, the ZNP was a comparatively steady and vibration-free platform for accurate visual observation and for the new electronic aids. A blimp, moreover, could slow down or hover over suspicious wreckage for a lingering examination. This ability proved indispensable for air-sea rescue work. Helicopters, it should be recalled, were still something of a novelty and not yet at sea with the fleet. By the war’s end, airships had participated in hundreds of rescues and special assistance errands. These varied from the delivery of charts to merchantmen and guiding stragglers back to their convoys to lowering food and provisions to survivors or hoisting them aboard. In one instance, a doctor was lowered to a surface unit to attend a seriously ill seaman.

The length of the average mission grew as the war progressed. An eight-hour patrol was typical the first year or so. Later, however, flight crews would return at dusk or well after dark as missions increased to fifteen or twenty hours or longer. Fortunately for these naval aviators, a K-type control car was—by aviation standards—comparatively roomy and comfortable. Fighter pilots were confined to cramped cockpits; patrol planes were somewhat less confining. But the patrol blimp was equipped with a large and streamlined car, which offered living as well as individual work spaces.

The control car was a straightforward structure, simple, strong, and lightweight. A K-car was simply a welded framework of chrome molybdenum steel tubes comprising ten transverse frames with connecting longerons above and below the floor level. Bracing was provided where necessary. Aluminum alloy sheeting was riveted to the framework as a covering or skin. Plexiglas windows provided all-around vision. The car was crammed with electronic equipment, small tables and instrument panels, storage drawers and racks, cables and chairs. The fuel tanks were overhead, the slip tanks and bomb hatch beneath the floor. The aft section contained chairs and bunks. A galley was built in and, at the extreme aft end, toilet facilities. Since in-flight watches were rotated, the men coming off duty could stretch their sea legs aft, read or doze in one of the three reclining chairs set into the deck, or sleep in one of the bunks. Hot food was available for all hands.

Primary responsibility during landing belonged to the GHO. Long lines in hand, ground handlers then secured the short lines. In addition to having radio (pigeons for radio silence), the King-ships were fitted with early radar, floating markers, sonobuoys, and hastily adapted ordnance—plus the all-important MAD for detecting, tracking, and attacking the U-boat. Mrs. F. J. Tobin

If the mission were convoy duty, the K-ship would rendezvous with her charges, “check in” with the convoy commander, and take up station to windward. From this vantage she could reach any point around the convoy in the least possible time.

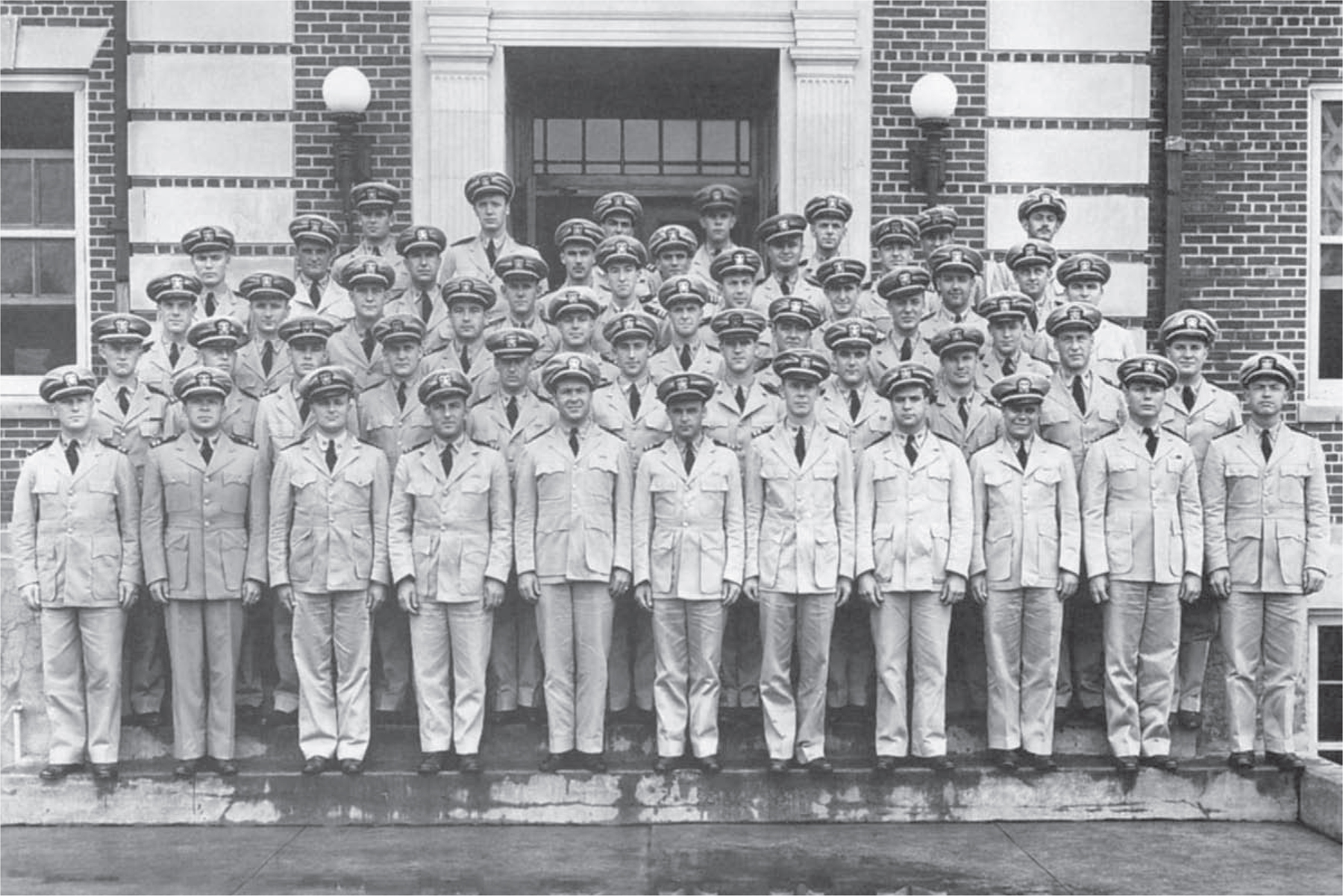

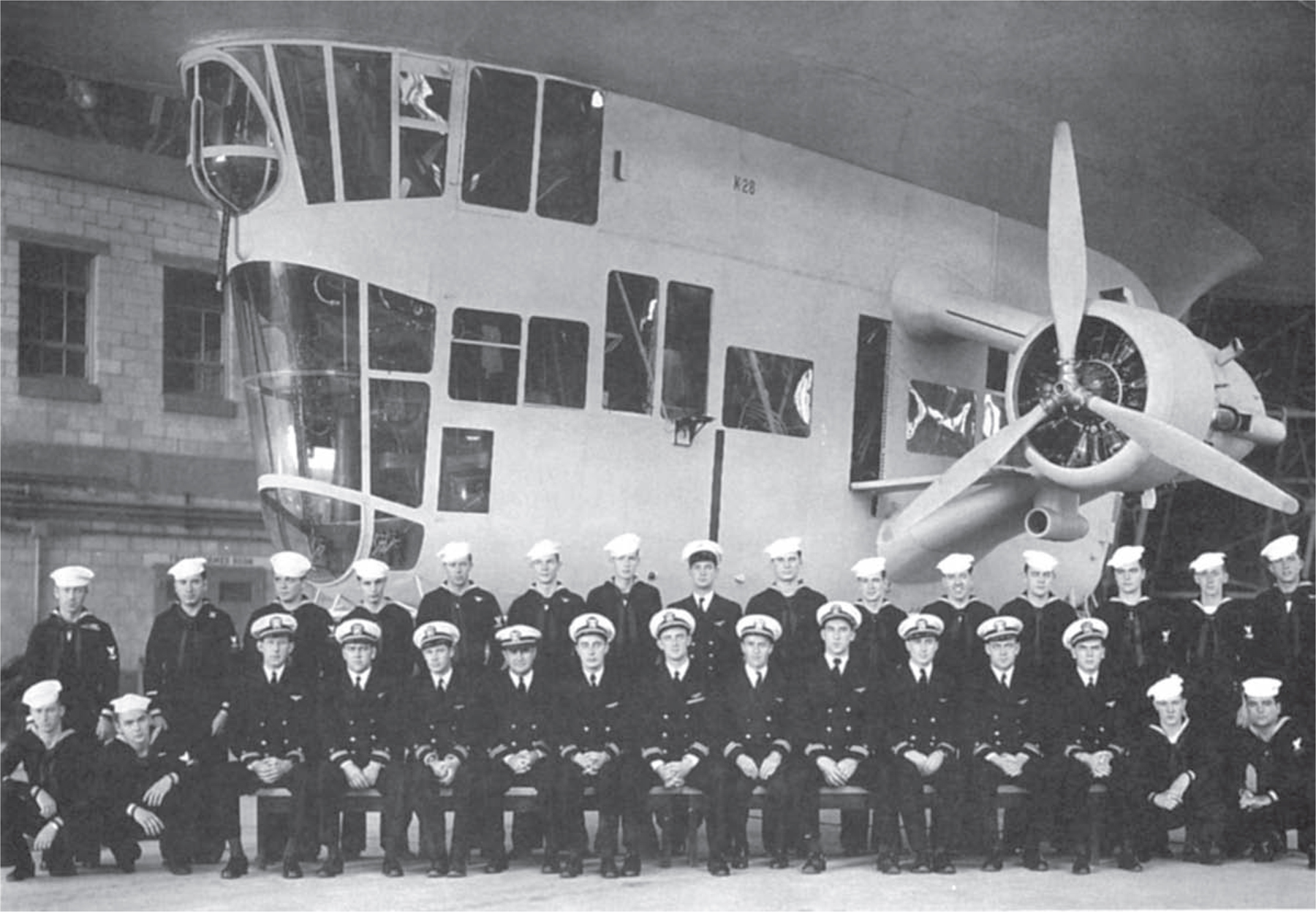

Airship Squadron Twenty-three (ZP-23), NAS Hitchcock, TX, 6 November 1943. Commanding officer: Lt. Cdr. M. H. Eppes, USN, front row, center. The squadron was commissioned at Lakehurst on 1 June 1943 for transfer to Hitchcock, where it operated within the Gulf Sea Frontier until decommissioned. Maximum ships assigned: five. Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

A convoy’s speed was dictated by its slowest vessel; evasion tactics slowed it still further. Surfaced, a U-boat’s diesels could drive a Type IX boat a maximum speed of nineteen knots. This exceeded any standard convoy speed. Submerged, however, the U-boat was capable of a maximum speed of about nine knots; usually it ran at about four. Its strategy therefore was to move into a favorable position directly ahead of and within about fourteen thousand yards of the convoy to mount an effective attack. The boat’s commander used his periscope sparingly (for a few seconds) as he stalked or as the convoy approached. Therefore, an airship’s lookouts had to be alert to recognize and report a periscope. An exhaustive search surrounding the convoy, and thorough investigation of all suspicious objects and sea conditions was essential if the attacker was to be detected before he struck.

Herein lies a fundamental premise of antisubmarine warfare during the Second World War: “keeping the submarines down,” especially with friendly shipping in the area. Forced underwater, pursuing U-boats were prevented from keeping pace with potential targets. Thus, it was not necessary to destroy or even to sight the enemy. By their presence, surface escorts and aircraft obliged their adversary to submerge; there, the speed and the difficulties inherent in tracking were such that the U-boat lost ability to reach a favorable position for attack or lost contact altogether.

If the escort airship sighted a periscope, a smoke flare was dropped to indicate a contact and a report made to the escort commander over the scene-of-action frequency. Aboard the blimp the crew responded to general quarters as all hands proceeded to their assigned stations. The command pilot would take over the elevator, one copilot manning the rudder. The second copilot took the bombardier’s seat, in the space directly in front of the two pilots; there, he armed his bombs. As the ZNP sped to target, the navigator prepared a contact report for the radioman and then made ready to record and photograph the approach, the attack, and the results. The radioman, meanwhile, had opened the bomb bay doors and transmitted the contact report to base. The mech, for his part, had set the fuel mixture to full rich, the pilot taking over the throttles. At sixty knots the charging aircraft was pressed to performance limits. Hence, a wary eye was kept on internal pressure. The assistant mech climbed into the machine gunner’s station above the bombardier.

On escort, an airship attacked a surface target immediately. On patrol, however, the blimp remained just outside anti-aircraft range and maneuvered to windward. At the first sign of the submarine’s diving, a ZNP attacked at full speed, the pilot diving his ship toward the spot. As he approached, the pilot used his “seaman’s eye” to integrate a number of critical variables: the distance, speed, and track of his target; the time of fall and depth setting for his ordnance. The attack was delivered at a minimum safe altitude—about one hundred fifty feet. It was standard to attack thirty degrees to a surfaced submarine’s track, releasing so that the bomb exploded just ahead of the conning tower.

A MAD contact presented a more difficult problem. The equipment’s inability to distinguish true targets from wrecks and geologic anomalies doubtless realized fruitless calls to General Quarters. Enemy below, the ZNP would deliver immediate attack if the target had been submerged less than about thirty seconds. But if the boat had been under too long, the contact had to be laboriously developed. A crisscross pattern might be flown to cover the area in which the U-boat could have traveled. Adopted as standard procedure, however, was the “trapping circle,” used to obtain a magnetic contact. A flare or marker was dropped a thousand yards before arriving at the point of submergence. Where the sub went down also was marked and, along the same course, a point a thousand yards beyond. A circle was then flown of a thousand-yard radius with the point of submergence as its center, dropping a marker every forty-five degrees of arc. This pattern was flown until the contact was obtained, or the radius was expanded to continue the hunt. When contact was established, the ZNP began tracking its quarry using MAD to determine the boat’s course and speed. A “clover leaf” pattern established the track of the evading target. Then “lazy eights” were flown across this track, dropping markers at each MAD contact. If an accurate plot were maintained, the approximate location and target heading was defined by the alignment of floating markers. A bombing run commenced.

The blimp attacked the contact in alignment with her markers, using a strong MAD signal to decide the point of release. The MAD gear later in the war, the Mark VI equipment for example, could automatically actuate the airship’s bomb-release mechanism. Accurate bombing was essential. To sink a U-boat, the depth charges had to explode within about fifty feet of the hull. But a near-miss also would yield results. A severe shaking up could break instruments, damage diving planes, jam machinery, or start a leak—any of which could reduce the fighting efficiency of the boat, not to mention frightening the crew and lowering morale.

After the attack, tracking was continued to maintain contact. The blimp might direct surface vessels or patrol planes to the scene and transmit information to forces joining the attack. The airship remained on scene until relieved or until the enemy had either been destroyed or had escaped.

There were innumerable variations on the conceptual situation outlined in the above paragraphs. If, for example, the blimp arrived too late at the point of submergence to use the MAD trapping pattern, sonobuoys were dropped to detect the underwater sound of a submarine.11 The tactical procedure resembled that for MAD trapping. A slow-speed platform, blimps found few opportunities to attack a surfaced U-boat. Moreover, the ability to track a submerged target and drop ordnance by instrument—on MAD signal—was realized only belatedly.

For Dönitz, the tide was ebbing. The answer to the threat had been found: convoys (as opposed to independent traffic) protected by experienced surface and air escort equipped with proper ordnance and special devices (radar, magnetic detectors, radio sonobuoys). No single panacea won the Atlantic campaign for the Allies. It was the combined weight of multiple elements—platforms, sensors, ordnance, training, coordinated experience—that would defeat Dönitz and his determined commanders. The mid-Atlantic “air gap” grew ever narrower until, in 1943, it was closed altogether. Now the submerged enemy could not operate without threat from the air. That spring, for the first time in the war, the U-boats failed to press home their attacks on convoys when favorably positioned to do so. The Allies’ defenses were beginning to prevail. German losses climbed, and morale dropped correspondingly. Compounding their dilemma, the U-Boat Command in most cases did not know how or why the boats were lost. This fed speculation, which bred rumors of secret Allied weapons and bizarre ruses.

By 1 May 1943, the U-Boat Command had more than 200 boats operating in the North Atlantic. Dönitz’s new building program called for 27 units per month. But the loss rate averaged 15 boats a month between February and April. In May, 10 were sunk in the first five days alone, and 31 more were sunk in that same month. By July, 113 U-boats had been sent to the bottom; by the end of 1943, 237 had been sunk—nearly three times the 1942 total. The Allies lost 597 ships that year, totaling 3.2 million tons.

For lighter-than-air, thirteen squadrons were operational by late 1943. Four operated within the Eastern Sea Frontier, three along the Pacific Coast, another three within the Gulf area, one in Caribbean waters, and two in Brazil. A number of overseas auxiliary bases had been constructed as refueling stops for ships being ferried to remote bases. The year ended with a naval airship fleet totaling 132 aircraft. The United States Navy was now operating the largest airship fleet ever constructed.

Operational statistics for 1943 were without precedent in the history of lighter-than-air aeronautics. Airships made more than 17,500 flights in the Atlantic and Pacific, totaling nearly 180,000 hours in the air. This included patrol and escort flights during daylight and also night missions, experimental flights, training hops, and the ferrying of ships between bases and commands. The Gulf Sea Frontier contributed another 48,800 hours aloft. Operations in the Caribbean Sea Frontier totaled 11,800 hours in 1943; the Brazilian theater compiled nearly 4,400 hours.12

“Number of Non-rigid Airship Delivered.” The Battle of the Atlantic was the one campaign that persisted from the first day of the war to the last, the U-boat threat unending. Goodyear

K-ships assigned to the detachment at Santa Cruz, Brazil. The hangar had been erected for South Atlantic service by Graf Zeppelin. Detachments deployed to forward areas such as South America and the Caribbean provided antisubmarine coverage for coastal shipping, including the bauxite trade from the Guianas. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

The year ended with a total of seventy-one Kingships operational under Fleet Airships Atlantic. These were distributed among ten squadrons—three of which were operating outside the continental United States. Lighter-than-air was logging ASW and convoy escort patrols from the Canadian border to southern Brazil, covering the three American coasts (East, West and Gulf) and the entire Caribbean basin.

Casualties in men and aircraft had mounted. Thirty-five accidents had taken twenty-one lives, nine airships, and one free balloon. A midair collision, the worst incident, had killed nine when K-64 from ZP-12 and the training ship K-7 collided in poor visibility off Barnegat Inlet, New Jersey. K-7 returned to base, but the squadron ship crashed and sank with but one survivor. Enemy action also had added casualties—for the first time in the history of the U.S. program. On the night of 30 October 1943, K-94 mysteriously burned and sank off Puerto Rico, taking eight crewmen with her. The cause remains unknown, but is listed as “possible enemy action,” since an Army B-25 was similarly lost in the same location only a few hours later. And one ZNP was lost to enemy gunfire. This unique drama occurred when, on the night of 18 July 1943, the K-74 was victim to a German submarine. On night patrol over the Florida Straits, the blimp made radar contact with an unknown object. Battle stations were manned. Making visual contact, the blimp engaged the U-boat, which was cruising on the surface. The target was the U-134 en route to Cuban waters. A gun duel ensued. Following an exchange of fire between K-74’s .50-caliber machine gun and the U-boat’s five-inch deck gun, the blimp was brought down by enemy fire into the envelope, engines, and flight controls. The wreck remained afloat until morning. The flight crew was rescued, but one man was lost to marauding sharks.13

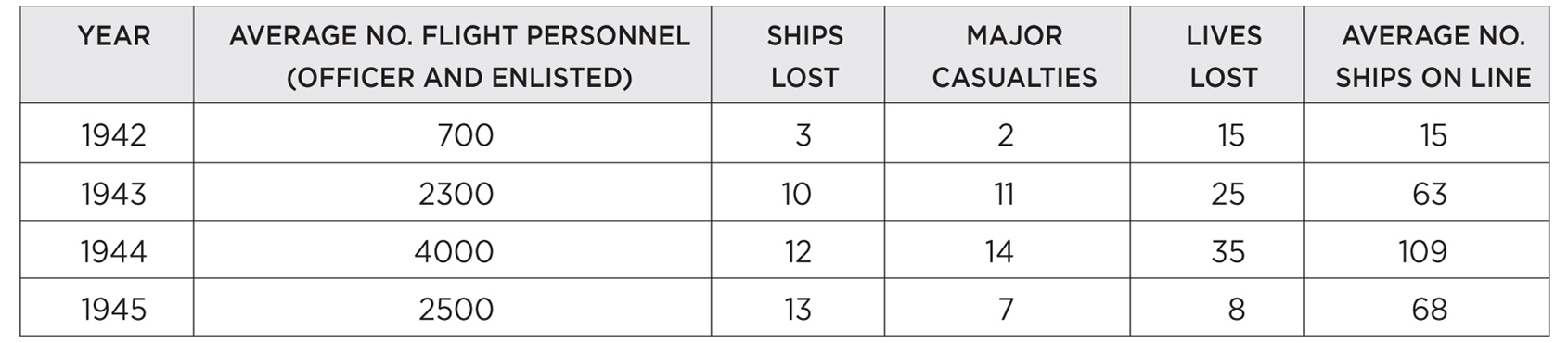

The nucleus of experienced officer and enlisted personnel was inadequate in number and distributed throughout the Naval Service when war was declared. With the training syllabi reduced, one officer student from Class XIX graduated with 123 flight hours, including one free balloon flight. Class XIX promptly assumed command responsibility throughout the organization. On 7 December 1941, Navy LTA had barely 200 officer and enlisted flight personnel. This multiplied to about 700 in 1942, 2,300 in 1943, and about 4,000 in 1944. Capt. F. N. Klein Jr., USN (Ret.)

LTA-qualified enlisted personnel supported the commissioned ranks. From barely 100, their number climbed to 3,000 by war’s end. Flight and ground crews were absorbed into a naval air organization that by 1945 was operating from bases along the East, Gulf, and West Coasts, the Caribbean, and as far away as Brazil and the Straits of Gibraltar. Here, the chief boatswain’s mate is emblematic of the rate. Lt. Cdr. L. E. Schellberg, USN (Ret.)

L-ships over the Santa Clara Valley. To ease the burdens at Lakehurst, Moffett Field became the center for primary flight instruction, Lakehurst the advanced school, allowing each to specialize. As well, Moffett was headquarters for commander, Fleet Airships Pacific, and the principal overhaul base for all Pacific Coast lighter-than-air. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Rosendahl, Chief of Naval Airship Training and Experimentation (center) on the mat at Lakehurst, 28 May 1943. In April, SecNav had approved a “126 operating ship” program plus spares. Established to increase program effectiveness, the CNATE command was responsible for training and for all experimental projects well into the postwar years. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

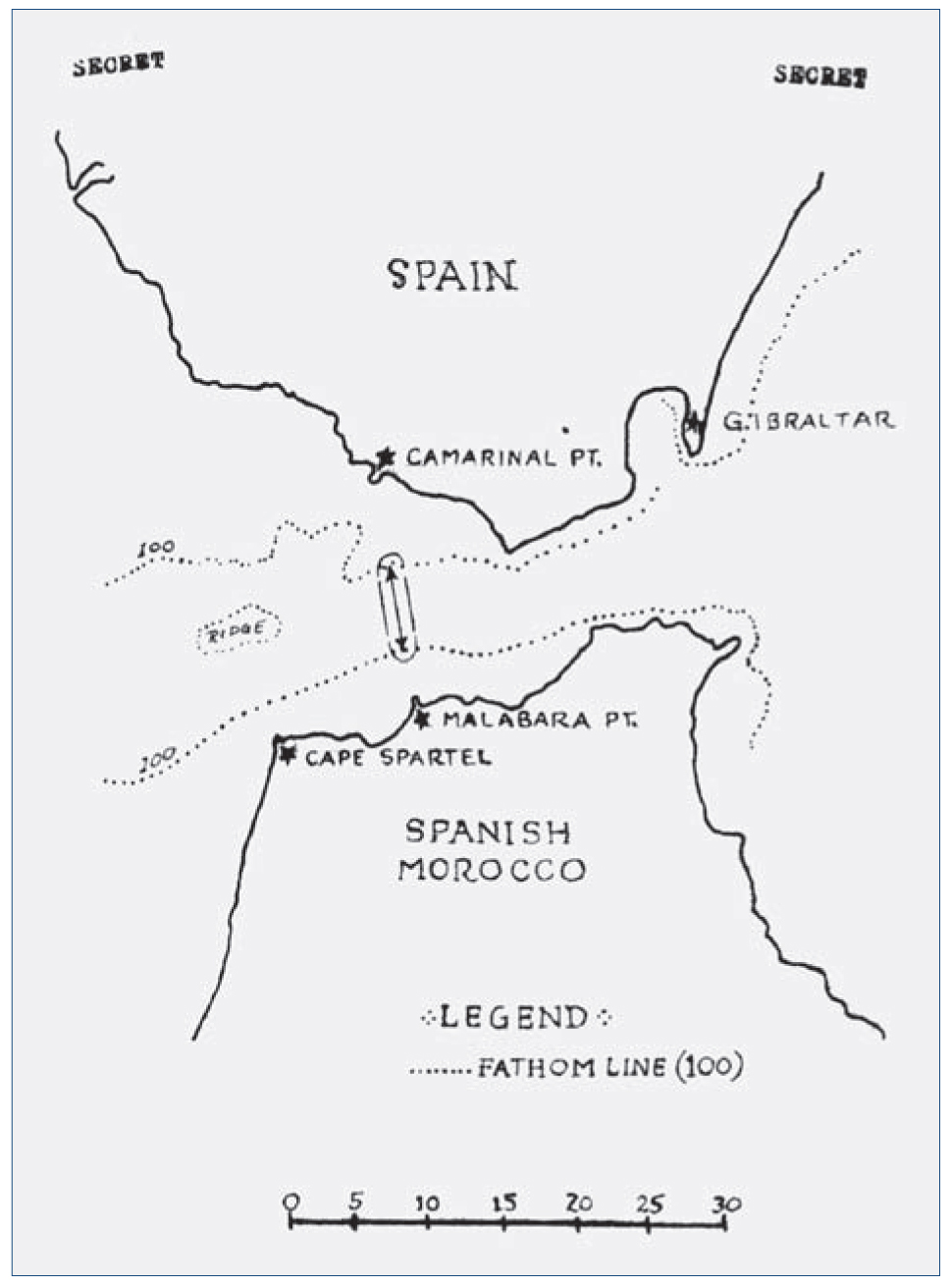

Possible reductions within lighter-than-air were already under consideration in August 1943—despite the first of repeated requests for additional antisubmarine assets in the Eastern Atlantic. In May 1944, ZP-14 would be ordered to move its area of operations to northwest Africa (Port Lyautery, Morocco) to augment the Allies daylight MAD barrier across the Strait of Gibraltar—entrance to the Mediterranean basin. Six King-ships were ferried across—the first nonrigids to log a transoceanic transit. Under the operational control of commander, Eighth Fleet, ZP-14 would log a singular record: low-level, dusk-to-dawn MAD barrier patrols across the “slot” as well as mine spotting both during and after VE day. Basing at expeditionary masts installed as far east as Sardinia and in Italy, detachments of ZNPs assisted Allied air and naval forces to clear the western Mediterranean.14

Strait of Gibraltar. Note the “race track” across the most narrow portion of the deep channel. The MAD gear was limited in its vertical range—the distance from detector to (submerged) target. For maximum penetration, low-level barrier patrols were flown from January 1944 to VE day to detect U-boats negotiating the slot. A pair of PBY-5As flew a daylight barrier; at dusk, the “MadCats” were relieved by two airships. NARA

ZPK-109 is cast off at Cuers, southern France. Note the radar “hat” below the car and MAD detector affixed to the envelope. The twin hangars were re-erected spoils from the First World War. Basing as far east as Italy, ZP-14 assisted efforts to clear the Mediterranean, pinpointing mines and directing sweepers to them. On its first three flights out of Sardinia, for example, King-109 spotted 268 mines. Airships would sweep ahead of President Roosevelt’s taskforce en route to Yalta. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

In the meantime, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO) had requested recommendations as to the advisability of cutbacks. The Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, Air (DCNO [Air]) responded on 27 August. Many of the as-yet undelivered airships, it was noted, were so far along in construction (or material ordered for them) that the department would be obliged to take them off Goodyear’s hands even if the contracts were canceled. At this time the Navy had sixty-nine K-type fleet airships on hand, another fifty-seven on order. And all the M-ships had yet to be delivered. Further, another thirteen training blimps were on order. In addition, more than 74 percent of the cost of expanding the LTA shore establishment had been obligated. Given this, only minor reductions seemed advisable. Accordingly, no change was recommended in the authorized program of 126 operating fleet airships and 21 spares. No further orders were to be authorized to cover attrition “at this time.” In short, the last wartime airships had been ordered.

A number of mast bases were dropped, however. Airship bases were to be limited to those “essential” for the deployment already approved. And personnel were restricted to the number necessary for the administration, maintenance, and operation of the program as then approved. Pilot training would be based on two crews for each ship within the continental United States and on three crews for each blimp operating overseas.

The first of the new M, or “Mike,” ships reached NAS Lakehurst on 29 November 1943. About half again as large as the K-type, M-1 represented the largest nonrigid airship ever constructed in the United States. The M-type, moreover, would retain this distinction until 1951.

Lakehurst at war. Mission: to provide a base and facilities for LTA units of the fleet; to serve as a major overhaul and fitting out base for airships; to support training and experimentation; and to serve as a major supply point for LTA logistics. At its peak, about 2,500 Navy, Marine, and civilian personnel were manning the naval air station. Mrs. E. P. Moccia

M-3 at Akron, 15 January 1944. Intended for operations in the tropics, the M-class was the largest blimp of the war, with a turret for the machine gunner and bombardier. Useful load was over 11,000 pounds, including eight depth bombs. M-1 was assigned to the Naval Airship Training and Experimental Command at Lakehurst; M-2, M-3, and M-4 to ZP-31, NAS Richmond, Florida. Although a formidable weapon of ASW, the “Mikes” arrived too late to realize a convincing contribution to war at sea. Goodyear

The control car consisted of a welded steel tubular framework built in three sections, which, due to the unusual length of the car, were articulated with universal joints. Light-gauge aluminum alloy and fabric skin covered the framework. TheM-type quickly became a favorite among pilots. The 117-foot-long car was roomy, comfortable, and unusually quiet since the engines were well aft of the forward section. Four bunks, cooking facilities, lockers, and sanitary equipment were provided for the convenience of the twelve- to fourteen-man flight crew.

Envelope volume for the prototype was 625,500 cubic feet, but this was increased to 647,000 cubic feet for the units that followed, then increased further to 725,000 cubic feet. Upon delivery, M-1 was assigned to the Naval Airship Training and Experimental Command. The useful load for M-4, delivered in April 1944, was 11,900 pounds. The airship’s two Pratt & Whitney Wasps gave a maximum speed of 69 knots for a 42-hour endurance at 50 knots or a range of 2,100 nautical miles in still air.15

Armament for the squadron ships consisted of eight bomb racks in two bomb bays, operated with electric remote releases from the bombardier’s instrument panel. A Plexiglas gun turret was located forward and was manually operated. A .50-caliber machine gun was mounted.

The M-ship was a formidable weapon of antisubmarine warfare. But it arrived too late to make a significant contribution to the war at sea. Twenty-two were ordered from the contractor; eighteen would be canceled. Only three Mike ships—M-2, M-3, and M-4—were therefore completed and delivered to Lakehurst between January and April 1944. On 6 April 1944, K-113, K-135, and M-4 reached the New Jersey station—the last LTA deliveries of the war.

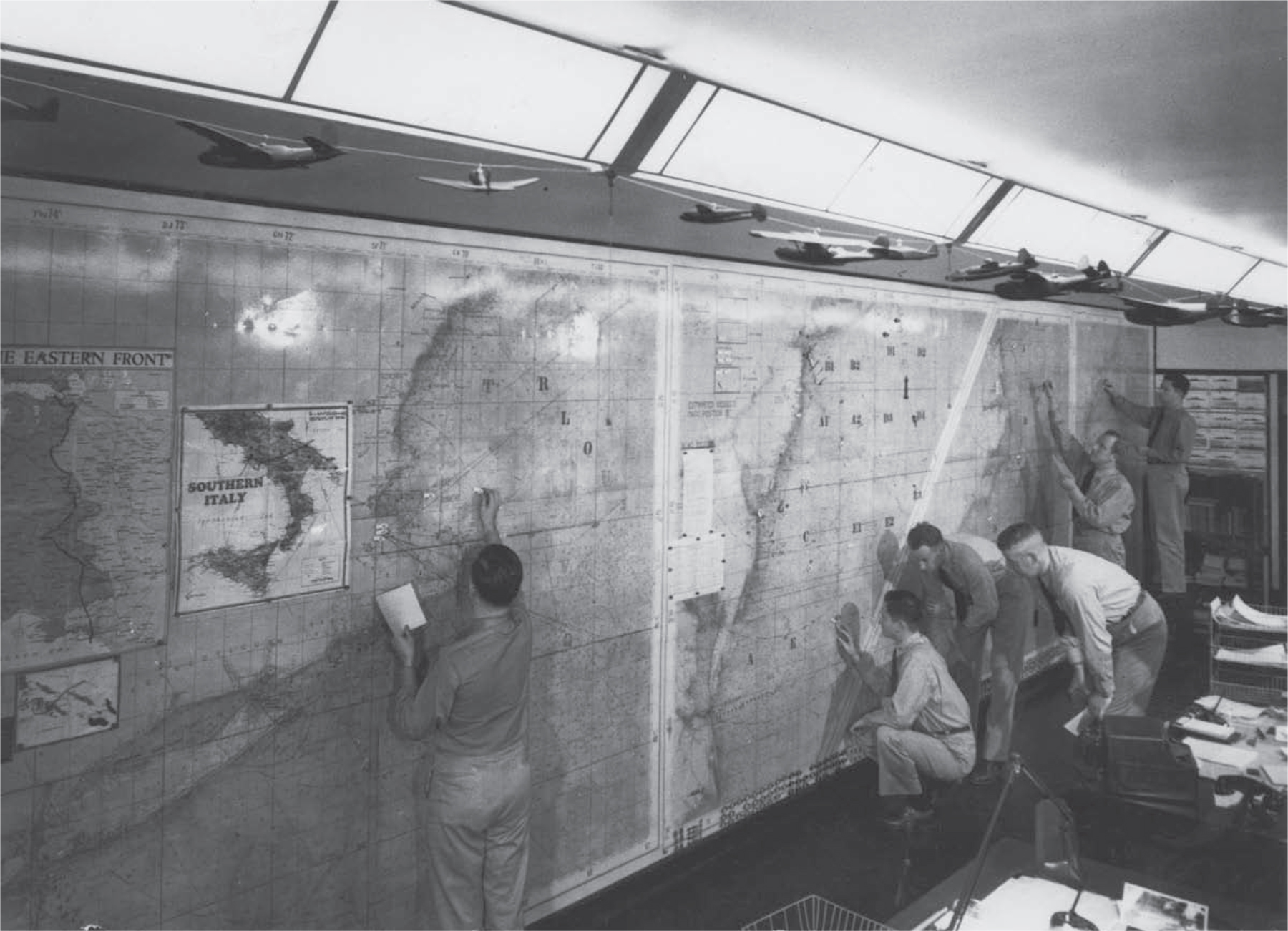

The Lakehurst operations room, 18 September 1944, nerve center of Fleet Airship Wing One. Under the authority of Fleet Airships, Atlantic, also headquartered on station, Wing One (four squadrons) was commissioned on 15 July 1943, Captain Raymond F. “Ty” Tyler (bending) commanding. C. E. Rosendahl/HOAC, University of Texas

Operating area chart (portion) for ZP-12, Operations Room for Fleet Airship Wing One, headquartered at Lakehurst. Patrol sectors “A” (Able) and “B” (Baker) were divided at latitude 40° north. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

By 1944 the Allies had reversed the balance of power at sea. But the submarine campaign by Germany was hardly over. To counter the Allied advantage, the Germans adopted a number of measures. Conning towers were rebuilt and fitted with machine guns against ASW aircraft; an acoustic torpedo was made available for use against escorts; a breathing pipe, or Snorchel, was fitted to supply fresh air at periscope depth. And work was under way to devise a way to reduce or jam enemy radar waves. Despite ever-decreasing resources, the U-boat building program persevered. The successes of the past were no longer sustainable, but the Allied forces tied up by the U-boat precluded their development elsewhere against Germany. “A let-up in the U-boat war is quite out of the question,” Hitler declared to Dönitz.16 Germany would carry on, even if it meant throwing away more boats and their courageous but increasingly inexperienced and dispirited crews.

In March 1944, the number of operational blimps reached 119—the high-water mark of the program. Never before had so many military airships been flown, nor would a fleet of comparable size ever again be deployed. Reductions begun in 1944 would, with temporary respites, persist for the next two decades, until the end of the program.

Overhaul on a Pratt & Whitney Wasp. K-ship engines were given a 30-hour and 100-hour check and were fully overhauled after 800–1,000 hours. The engineering officer was responsible for the maintenance and repair of the two 425-horsepower units for his ship. Capt. F. N. Klein Jr., USN (Ret.)

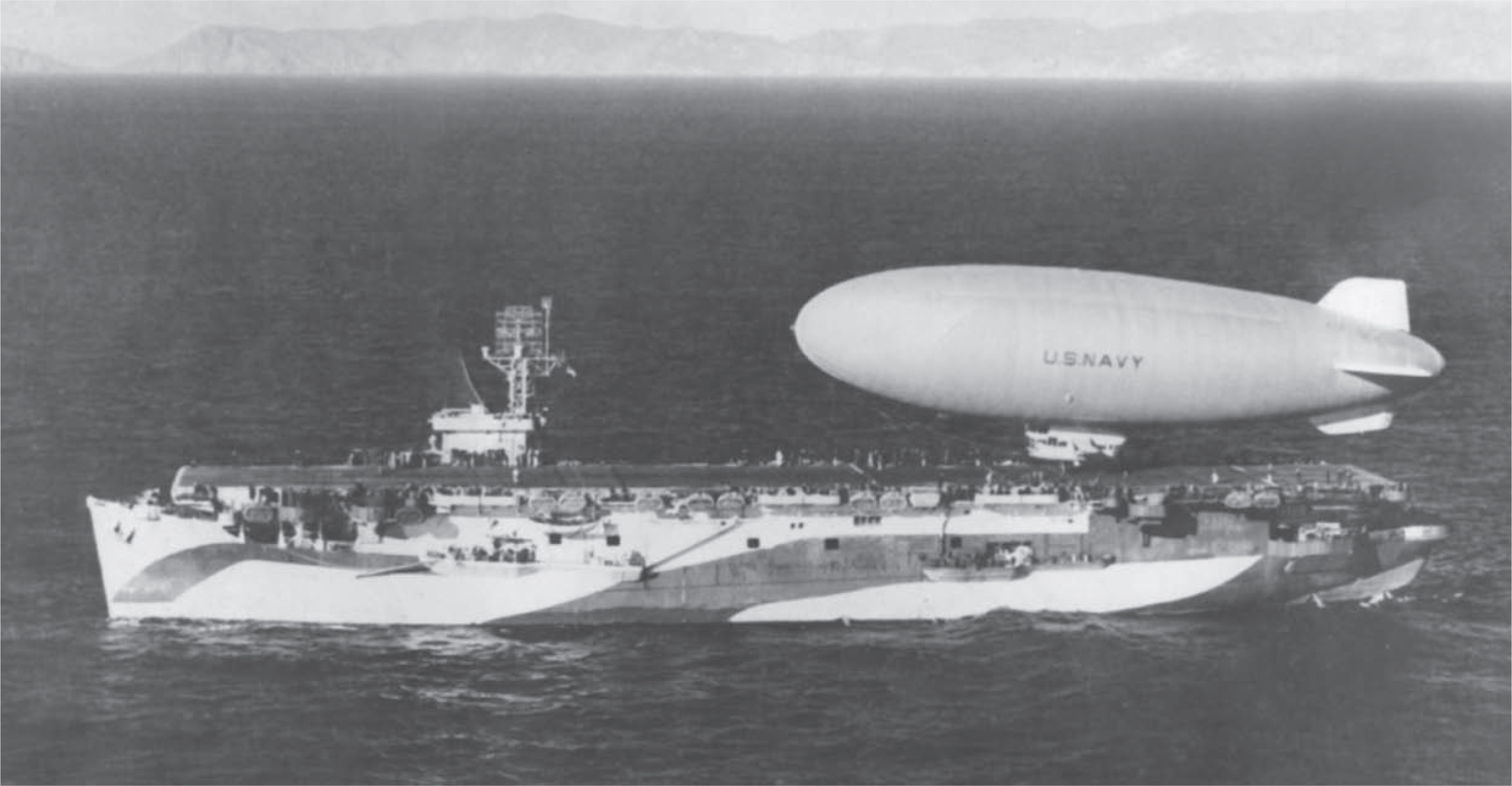

ZPK-29 (ZP-31) and escort carrier Altamaha (CVE-18) off San Diego, 4 February 1944. The Pacific war had shifted half an ocean away. In a test of joint operations to open the door to deployment into the West Pacific, this was the first such touchdown by U.S. Navy LTA. That August, a six-landing exercise demonstrated refueling/replenishment. Feasibility notwithstanding, no ZNP accompanied U.S. naval forces for mine spotting or for ASW against Japanese forces. Author

The war entered its final months. The year 1944 proved to be a costly one for the program, the worst of the war. Nearly forty accidents involving loss of aircraft and major casualties had cost twelve patrol ships and thirty-five men. Lakehurst had witnessed the most tragic accident, when the training ship K-5 failed to clear the west end of Hangar No. 1 during practice takeoffs and landings. The car crashed into the upper ledge, causing the bag to rip and the car, after hanging for a moment, to crash to the mat. Six officers and four enlisted men were killed. On the West Coast, K-111 out of Del Mar struck the heights of Santa Catalina Island in dense fog. Her gasoline and four depth charges exploded, killing six of the eight men on board. The two survivors were blown clear. Oddly, sixteen men were lost in six separate incidents when their patrol ships flew into the water.

An Allied victory in 1945 was inevitable. But the routines, the engagements, and the casualties continued. Between January and May 1945, nearly 100 merchant ships and another 153 U-boats were sunk. Lighter-than-air lost four aircraft and eight officers and men before VE day was proclaimed by the new president, Harry S. Truman.

ZPK-53 in the sea off Jamaica, 7 July 1944, having flown into the water. One crewman was killed. The year 1944 saw the most casualties: thirty-five lives along with twelve patrol ships. In all, LTA would lose seventy-seven officers and crewmen, plus there were six fatal accidents involving ground handlers. The majority of losses and major casualties were traced—as with this accident—to personnel error. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

Airship Utility Squadron One (ZJ-1), 15 June 1945. Commissioned in 1944, it provided photographic, calibration, torpedo recovery, and other utility services to the Atlantic Fleet. ZJ-1 logged nearly 7,000 hours during 1944–45 before the unit was decommissioned. By September 1945, indeed, most of the wartime program stood dismantled. Mrs. E. P. Moccia

The cutbacks in Atlantic Fleet pilots and aircraft climbed dramatically. In mid-June, Fleet Airship Wing Two at NAS Richmond was formally decommissioned; one month later, Fleet Airship Wing Four at Recife (Brazil) also was decommissioned. The United States was still at war with Japan. The Western Sea Frontier flew more than forty-seven thousand LTA hours between January and the end of August, but the number of patrol and escort flights dropped sharply that summer. Indeed, no patrols were made within the entire Sea Frontier after June 1945. On 2 September 1945, Japan formally surrendered on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Today, the wartime contribution of the nonrigid airship is virtually unknown. Its record is commendable nonetheless. Within the Atlantic theater of operations, 22,155 operational flights (excluding training, experimental, utility, ferry, and other nonmilitary flights) were flown by U.S. Navy lighter-than-air in the Second World War. Another 13,800 flights were logged over the Pacific. Combined, 57,710 sorties of all types were made in Atlantic and Pacific areas, a total of 545,529 hours in the air, or nearly 23,000 days. This does not include the 280,000 hours flown by training ships assigned to NAS Lakehurst and NAS Moffett Field. An estimated 89,000 surface vessels were escorted by blimps during the war—most in the Atlantic. Fifty thousand of these were in areas where enemy submarines were known to be present. With one possible exception, not a single vessel under escort was lost to attack. Airships had participated in a number of joint actions resulting in a possibly damaged or positive U-boat sinking—a “kill.” But no enemy boats were recorded as “sunk” by LTA alone—a commendable if stumbling performance.17 In the joint battle space of the trade war, conventional operating forces—destroyers, carriers, fleet HTA units—had proven more consequential.

On VE day, Navy LTA was operational in North, Central, and South America, Mediterranean Europe, and from northwest Africa—in action to seaward off four continents. The problem of harborage away from base had proven formidable: airships require a mast, flight and ground personnel, plus housing and helium storage. Still, operational facilities had ranged from complex hangar bases to expeditionary sites in jungle clearings. Author

Success in war is a weave of variables: training and experience, contingency and coincidence, organizational politics, priorities, personalities. Much depends on chance—a factor in any profession. When antisubmarine opportunities were ripe, airships were few—their sensors (as yet) quirky laboratory prototypes. When blimps were deployed in strength by personnel adapted to the latest systems, tactics, and weapons, few U-boats were raiding coastwise shipping.

The number of available aircraft had fluctuated wildly, indeed. When the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor, the LTA program had ten airships of all types in inventory and one naval air station—Lakehurst. One month later, six airships were operational in all areas of command. The number climbed slowly to 28 within a year of the outbreak of hostilities, peaked at 119 ships in March 1944, then reduced to about 81 by VE day, and finally fell to 30 aircraft in September 1945. The year 1944 was the most active of the war: an average of 109 airships on line for a total of 252,822 hours in the air.

Proportionally, the LTA program suffered significant wartime losses. Thirty-eight aircraft, including thirty-four K-ships, had been lost. Major accidents involved another thirty-four aircraft. Seventy-seven officers and men were killed; ground handlers were involved in six fatal accidents. Enemy action had accounted for at least one fatality, equipment design and matériel for considerably more. Personnel error was deemed responsible for most of the losses and major casualties incurred during nearly four years of hostilities.

NAS Richmond after the general collapse and fire of 15 September 1945. A major overhaul base for the Atlantic Fleet, hurricane-force winds and uncontrolled fires consumed three timber hangars sheltering 367 planes and 25 airships—thirteen inflated, twelve in storage. A complete loss, Richmond vanished from the list of naval air stations. NAA/R. G. Van Treuren

U.S. Navy lighter-than-air had benefited from unprecedented official attention in terms of appropriations, aircraft, equipment, personnel, and support facilities. The contrast with the fiscally moribund 1930s is startling. The wartime program cost the taxpayers about $227,831,000 altogether. Of this expenditure, slightly more than $58,000,000 was for aircraft, another $14,500,000 for helium.18 The principal outlay, however, had gone for shoreside infrastructure, that is, for air station support and related costs. However generous the totals might have appeared at the time, such outlays were dwarfed by the United States’ prodigious spending to fight the Second World War—39 percent of the gross national product on defense. The official recognition that had come to naval air power would not endure in the postwar period. The interval 1940–45 would prove to be a high-water mark for the program.19

Airship Statistics for the Second World War

Aircraft and personnel losses were the result of ground handling accidents, material failure, pilot error, weather, and other causes. One ship, possibly two, was lost to enemy fire.