Four LTA wings were operational in January 1945—the largest lighter-than-air force ever. LTA would never again be as well integrated into the naval service. The immediate postwar years were marked by a precipitous demobilization. Airships were scrapped, sold, or placed in storage. These reductions paralleled similar actions throughout the Navy as surface ships were “mothballed” (retired to a reserve fleet). Airplanes were stored, shore stations deactivated, and military personnel discharged by the tens of thousands. Within a year the number of men in naval aviation had dropped to one-quarter of the wartime peak.

Why, given its wartime record, was the airship program again relegated to a subordinate status within the Navy? Some of the reasons remain unclear even today. Yet there are parallels with the embattled politics of the large military airship of the interwar years. Official skepticism and the chronic shortage of aviation funds had resulted in miserly budgets, which, in turn, had stunted overall development. Then, faltering commercial efforts and spectacular crashes soured public enthusiasm. Official confidence, always a fragile commodity where large airships were concerned, had by 1939 reached the vanishing point. The lowly blimp inherited this troubled legacy. When Los Angeles was dismantled in late 1939 and the two Graf Zeppelins destroyed a few months later, the rigid airship as a commercial and military entity vanished. Only the nonrigid remained—and it had benefited enormously from the combat experience and technological advances of the war. But so had heavier-than-air aeronautics. By 1945, it seemed that the airplane had progressed too far for the ZR to catch up. With the return of peacetime penury, moreover, the battle for the dollar was again joined. Now it was the blimp that had to justify itself as a legitimate part of modern naval warfare.

Following the Second World War the various constituencies of the U.S. military establishment began to promote their respective wartime achievements. Within the Navy, carrier aviation would dominate postwar naval policy and, thus, Navy politics. The airship’s contributions were largely ignored. Essentially a defensive weapon, the nonrigid lacked the glamour of more established naval hardware: surface ships, submarines, and aircraft made famous by years of global conflict. Published accounts of the Battle of the Atlantic seldom mention the airship; even official histories of the war at sea tend to ignore its contributions. Moreover, poorly prepared for war and comparatively low among competing budgetary and matériel priorities after Pearl Harbor, the program was deprived early on of the highly specialized equipment and developmental attention that might have produced dramatic combat successes. The raw fact was that no enemy submarines had been sunk by a nonrigid airship. No number of official “Well Dones” for its other services could possibly offset this apparent wartime failure.

The size of the LTA organization relative to the rest of the Navy continued to limit its political influence. The voice of lighter-than-air was always a tiny one. In total nearly five thousand pilots and enlisted aircrewmen had been trained between 1941 and 1945—less than the total complement of two carriers. Moreover, no flag-rank command concerned itself primarily with airships. Consequently, the shapers of postwar naval aviation had little incentive to work out a place in fleet operations that might exploit the special characteristics of this unique weapon system.

By mid-1946, the lighter-than-air organization was but a fraction of its wartime peak. All Fleet Airship wings had been decommissioned and the number of bases slashed to five. All overseas squadrons had retreated home for decommissioning. Only two ASW squadrons were in commission: ZP-31, headquartered at NAS Santa Ana and Lakehurst’s ZP-12. They were redesignated ZP-1 and ZP-2, respectively, and by year’s end had four ships operational. Another eight R&D airships were attached to Chief of Naval Airship Training and Experimentation (CNATE) at Lakehurst.

NAS Lakehurst flight line. The first postwar class convened on board in April 1946. The following year, training was integrated into the flight-training program at Pensacola. In 1954 LTA pilot training was shifted to NAS Glynco, Brunswick, GA. Capt. J. C. Kane, USN (Ret.)

The number of LTA personnel was slashed to approximately fourteen hundred officers and men. Nevertheless, in January 1946 the Bureau of Personnel announced that applications from regular Navy and reserve officers would be received for LTA flight training or refresher training. That April, the first postwar class convened at Lakehurst. And in concert with the newly activated Naval Air Reserve Program, a formal LTA reserve-training program was established in June with the formation of the Naval Air Reserve Training Unit (NARTU) operating a single squadron at Lakehurst, ZP-51. Reserve operations would persist into the latter 1950s, with Lakehurst the center of all training until 1954, when pilot training was transferred to NAS Glynco.

In August 1947, all squadron activity on the West Coast ended. The headquarters of ZP-1 was relocated to the Naval Air Facility (NAF) at Weeksville—the squadron’s three “Mike” and seven “King” ships ferried cross-country to new homeports. Though no one knew it at that time, operationally, LTA on the Pacific Coast was finished. (In 1951, a two-ship reserve training unit would be established at Santa Ana.) The three-thousand-mile transcontinental transfer was logged without mishap. The M-ships were flown to Lakehurst, the K-type ferried to Weeksville and to the Glynco detachment. Thus, on 30 June 1948, naval airship strength totaled eighteen aircraft: eight fleet units assigned to two ASW squadrons, another eight for R&D, and two ships for reserve training. No significant changes would occur until the Korean crisis and its associated buildup. U.S. Navy lighter-than-air was alive if hardly prospering.

A K-ship assigned to the Naval Air Reserve Training Unit, Oakland, CA. The fundamentals of operating submarine and airship are similar: both are submerged in a fluid, deriving buoyancy from the weight of fluid displaced. NARTU was established in 1947 with a single squadron, ZP-51, at Lakehurst. In 1947, all fleet squadron and Reserve activity on the West Coast was ended. That year also, the rigid airship vanished from official naval policy. Author

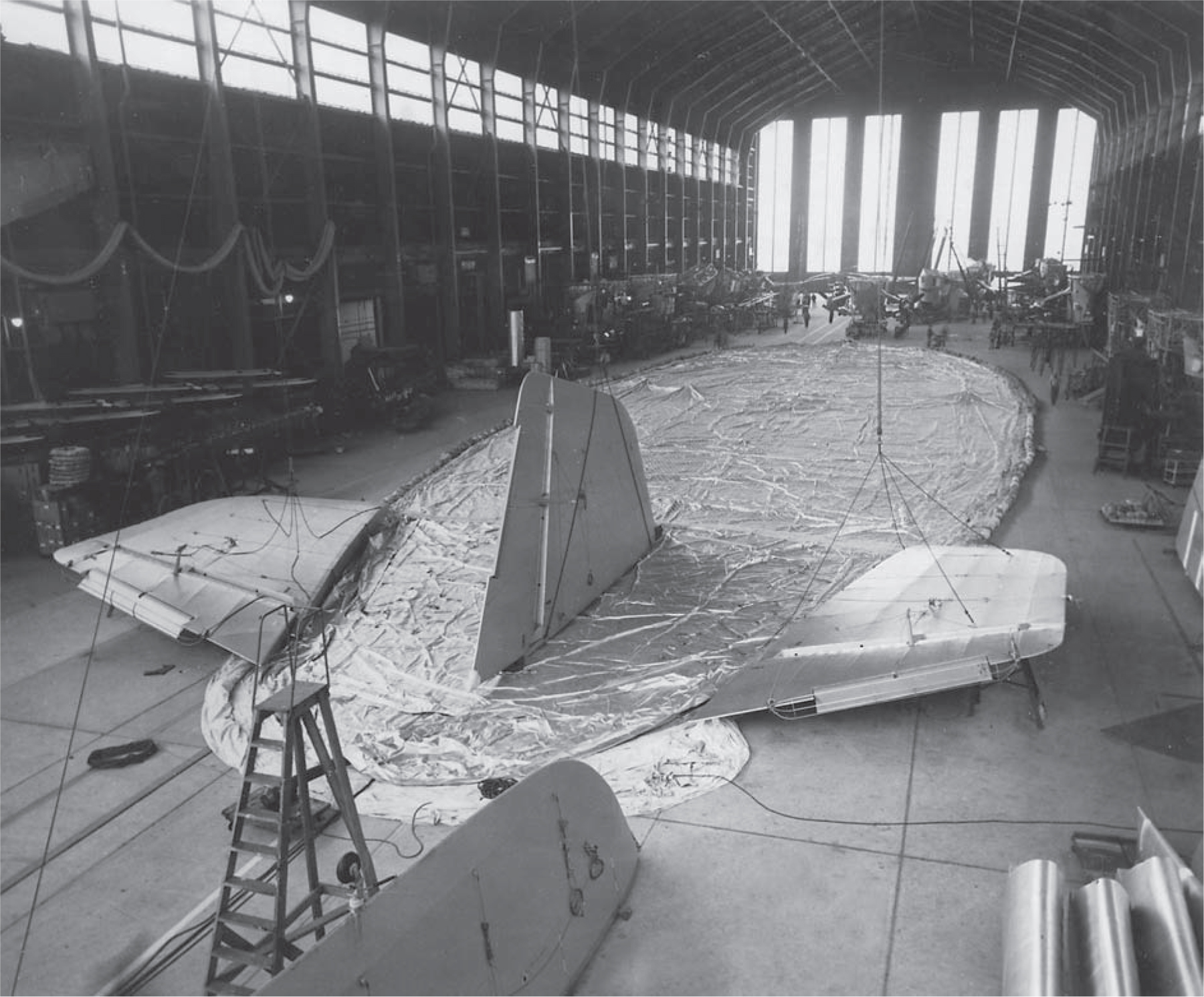

Ready for inflation, Hangar No. 2, Assembly and Repair Department. In July 1948 the department at Navy and Marine Corps stations was renamed Overhaul and Repair (O&R). Lakehurst was unique in servicing airplanes and helicopters as well as airships. In 1961 Lakehurst O&R would be decommissioned along with the last LTA squadrons in the Navy. USN courtesy Lt. H. R. Rowe, USN (Ret.)

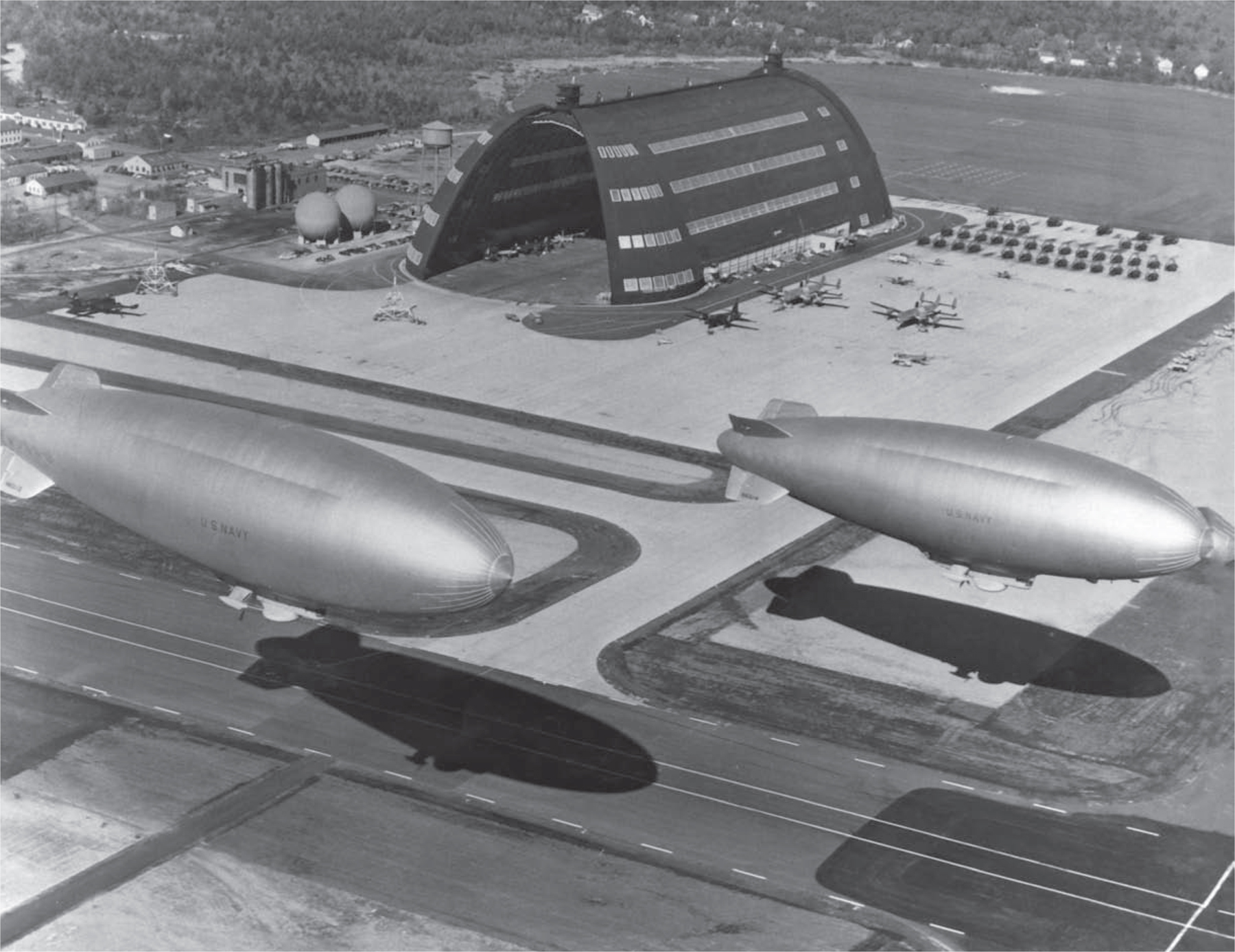

Two K-ships assigned to ZP-2 near takeoff, NAS Glynco, March 1953. Airship Squadron Three (ZP-3) was commissioned in 1950. Primary Mission: to conduct all-weather antisubmarine operations, that is, to detect, track, and destroy enemy penetrations—singly or in conjunction with other air, surface, or sub-surface forces. Due largely to the Korean emergency, the early 1950s seemed to portend a bright future for Navy lighter-than-air. The years 1948–55 saw buildup in organizational strength and operational aircraft—and authorization of a prototype ASW design: the “Nan” ship. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Official naval policy with respect to airships, last defined in July 1940, and as approved by the Secretary of the Navy on 23 January 1947, continued to include blimps, but all mention of the rigid type was deleted. The General Board after thirty years had formally scrapped the rigid airship.

The total naval aviation budget for 1948 included nearly $4 million for lighter-than-air, less than 1 percent of the total. Significantly for the future, however, this figure included $1.5 million for a new prototype, the N-class—the first such initiative since the war. The N-ship (later designated ZPG-2) would prove to be an excellent design—the basic and most versatile LTA airship platform of the postwar program.

It should not be assumed that the Navy was the only operator of lighter-than-air craft in postwar America. The Goodyear Aircraft corporation had resumed its aerial operations in 1946–47, beginning where the Goodyear Fleet had left off in 1942. Components from seven L-ships were purchased from the War Assets Administration and the former K-28 acquired outright from the government. Public relations flights resumed with six aircraft. But for the first time Goodyear had competition. Howard Hughes was using a surplus Navy blimp to promote his new film The Outlaw. The most determined enterprise, however, was the Douglas Leigh Sky Advertising Corporation. Leigh was a well-known name in outdoor advertising, most notably for his animated signs along New York’s Times Square. In February 1947 the young executive purchased twenty-nine surplus blimps for aerial promotion. About half (K- and L-ships) were cannibalized for spare parts. Hangar space was leased from the Navy and an East Coast headquarters established at Lakehurst. Effectively, Leigh’s operation was a reserve-training program for the Navy at an excellent price.

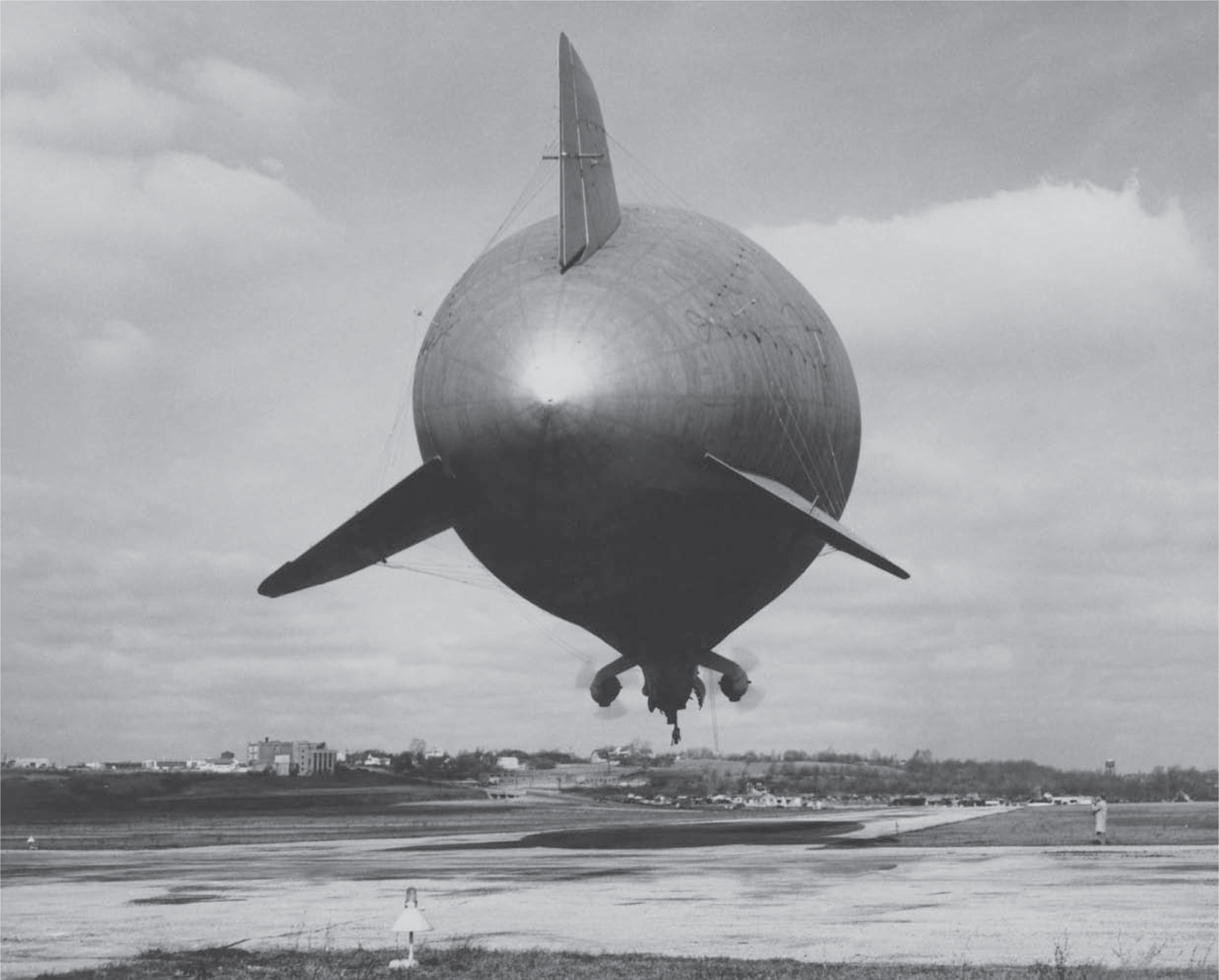

N-1 arrives at Lakehurst, 17 June 1952, prototype for the N, or “Nan,” series. Deploying superb detection and tracking gear, the ZPG-2 (final designation) would prove to be the most versatile ASW platform in the larger naval background of the 1950s. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

In September 1946, the actress Elizabeth Taylor christened the first Leigh airship at ceremonies in the Lakehurst hangar. The next day, the “MGM Airship” inaugurated aerial operations. A second ship promoting the Ford Motor Company was launched, and a third, the “Tydol Airship” (ex-K-76), was pressed into service early in 1947. East Coast operations were promising, so a similar enterprise was organized in California, with headquarters at Moffett Field. Flights using an L-ship for promotion commenced in spring 1947. Long-range plans called for about four blimps on each coast as well as barnstorming using a truck unit and extra crew for support on the ground.

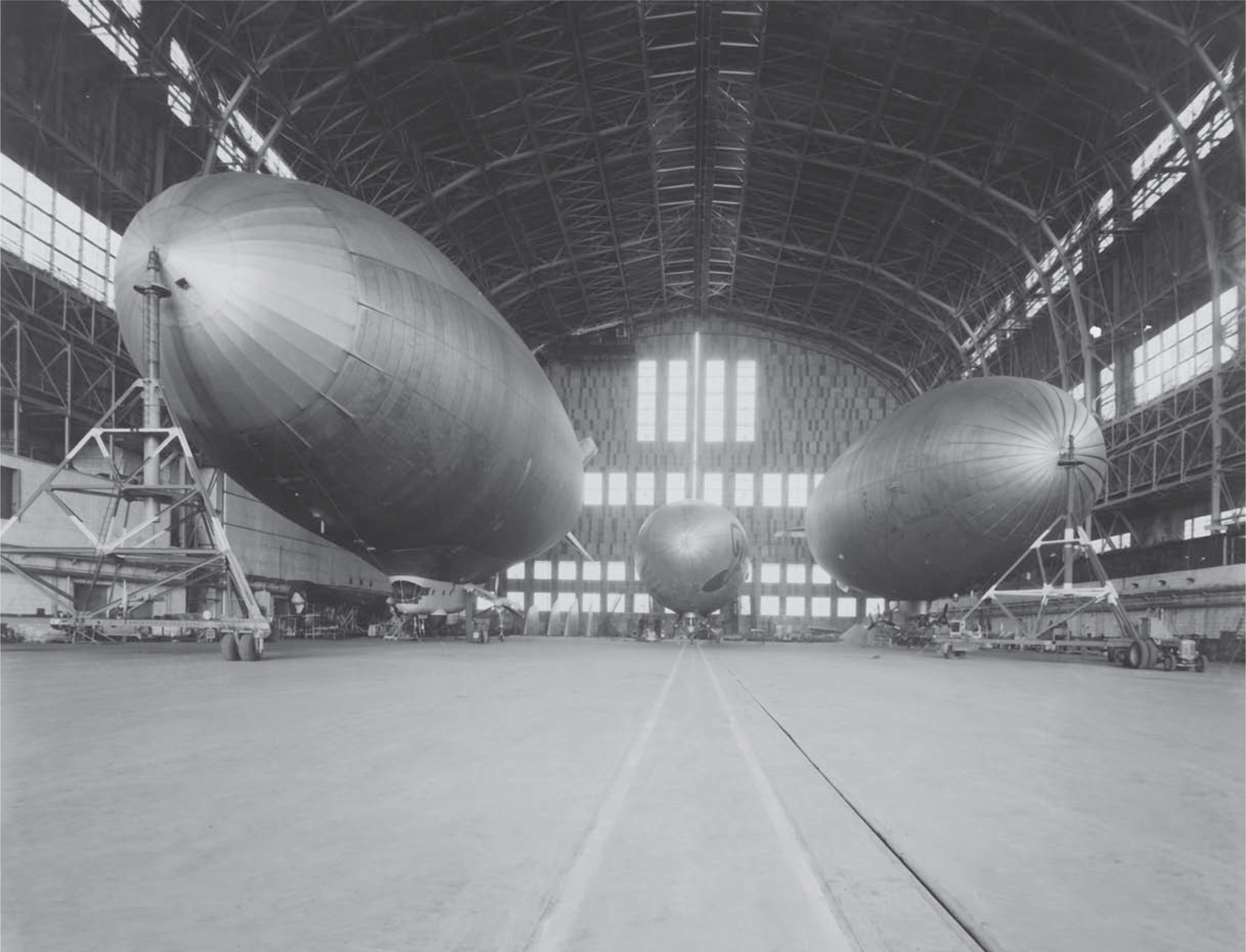

N-1 at Lakehurst, 18 November 1952. Preliminary ground and flight tests for the prototype were disappointing, mandating further evaluation to explore improvements. The Board of Inspection and Survey (BIS) trials for N-1 persisted into 1953. Here the new ship dwarfs a K-type. Docked near the doors is an L-ship operated by the Douglas Leigh Sky Advertising Corporation—a Ford logo on the bag. Leasing space and operating surplus blimps, Leigh would operate from Lakehurst into the early 1950s. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

The years 1948–53 were active ones for Navy lighter-than-air. A healthy if not to say dramatic buildup in aircraft and organizational strength was authorized, largely in response to the Korean emergency. The number of operational ships doubled, two ASW squadrons commissioned. In addition, in 1949 Fleet Airship Wing One was recommissioned at Lakehurst. As well, contracts for the new N-ship were signed in May 1948. Design and performance specifications for the prototype helped generate a renewed sense of anticipation and vitality throughout the organization.

Development efforts to assess and improve the range, endurance, and overall performance of the airship platform had begun almost immediately after the war. The first M-ship, XM-1, attached to the CNATE command, began a series of extended test flights to collect data. The longest flight of XM-1 set an unrefueled endurance record for all aircraft types that remained unbroken for eight years, until an N-ship, only a paper prototype in 1946, broke the record during its acceptance trials in 1954. On 27 October 1946, XM-1 departed Lakehurst with a flight crew of thirteen. Slowly, the big ship proceeded south along the coast to Georgia, then seaward to the Bahamas, west to Florida, then to Cuba and the Gulf of Mexico before returning north and landing at Glynco on 3 November. The ship had been in the air 170.3 hours—more than seven days—and had not yet reached its limit of endurance. Much of the flight was made on one engine with the other secured and the propeller feathered in order to achieve the best possible fuel economy.

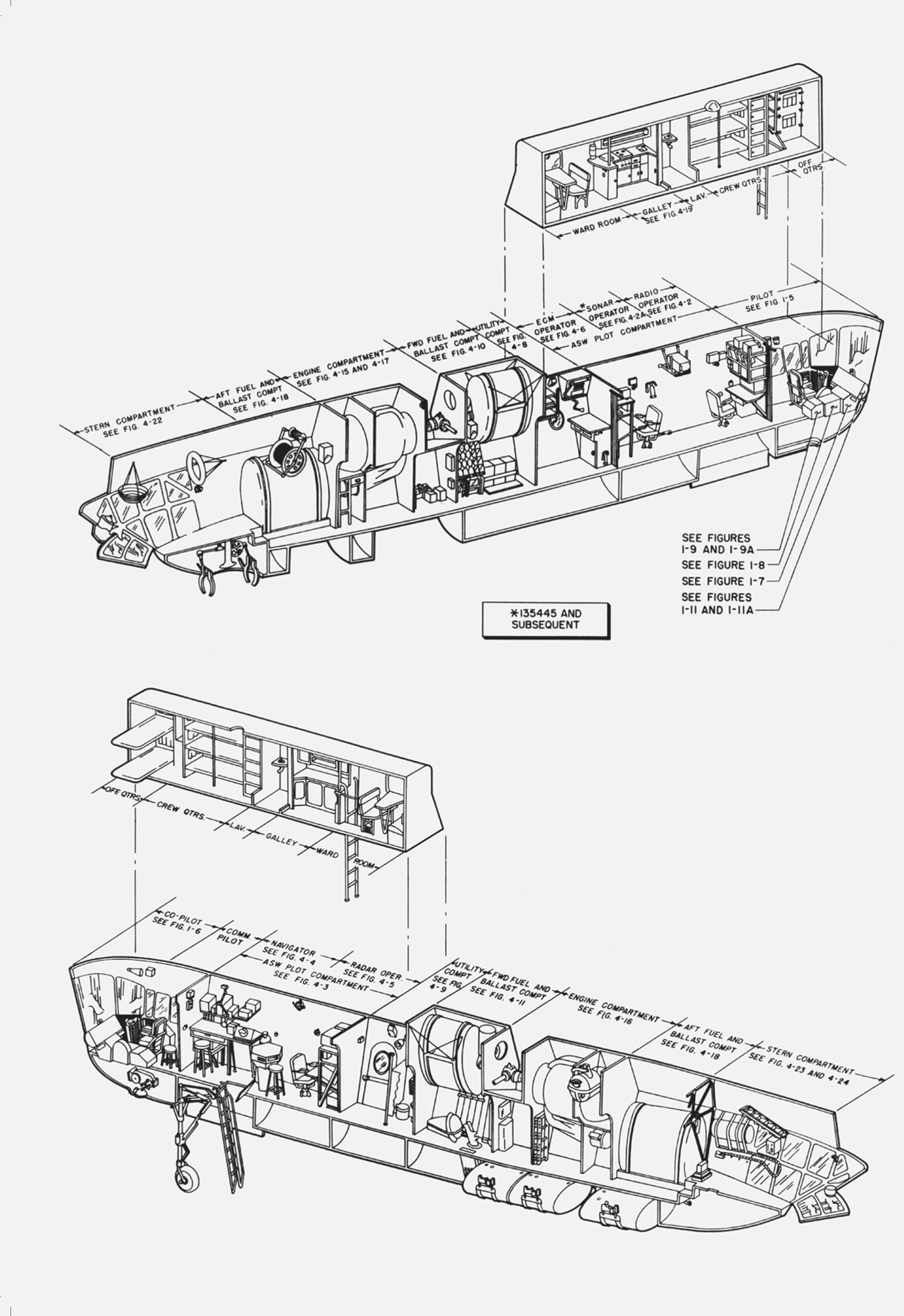

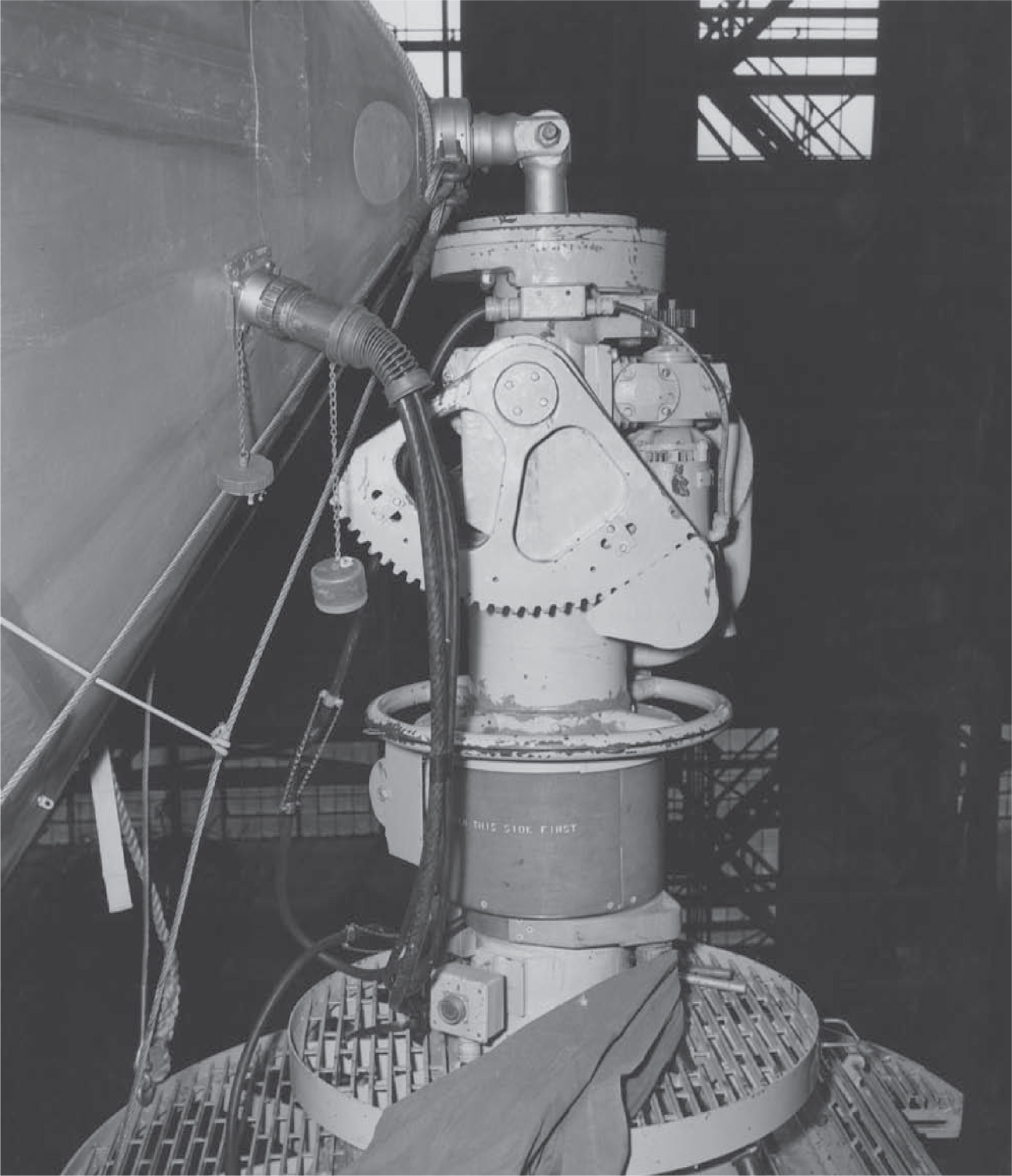

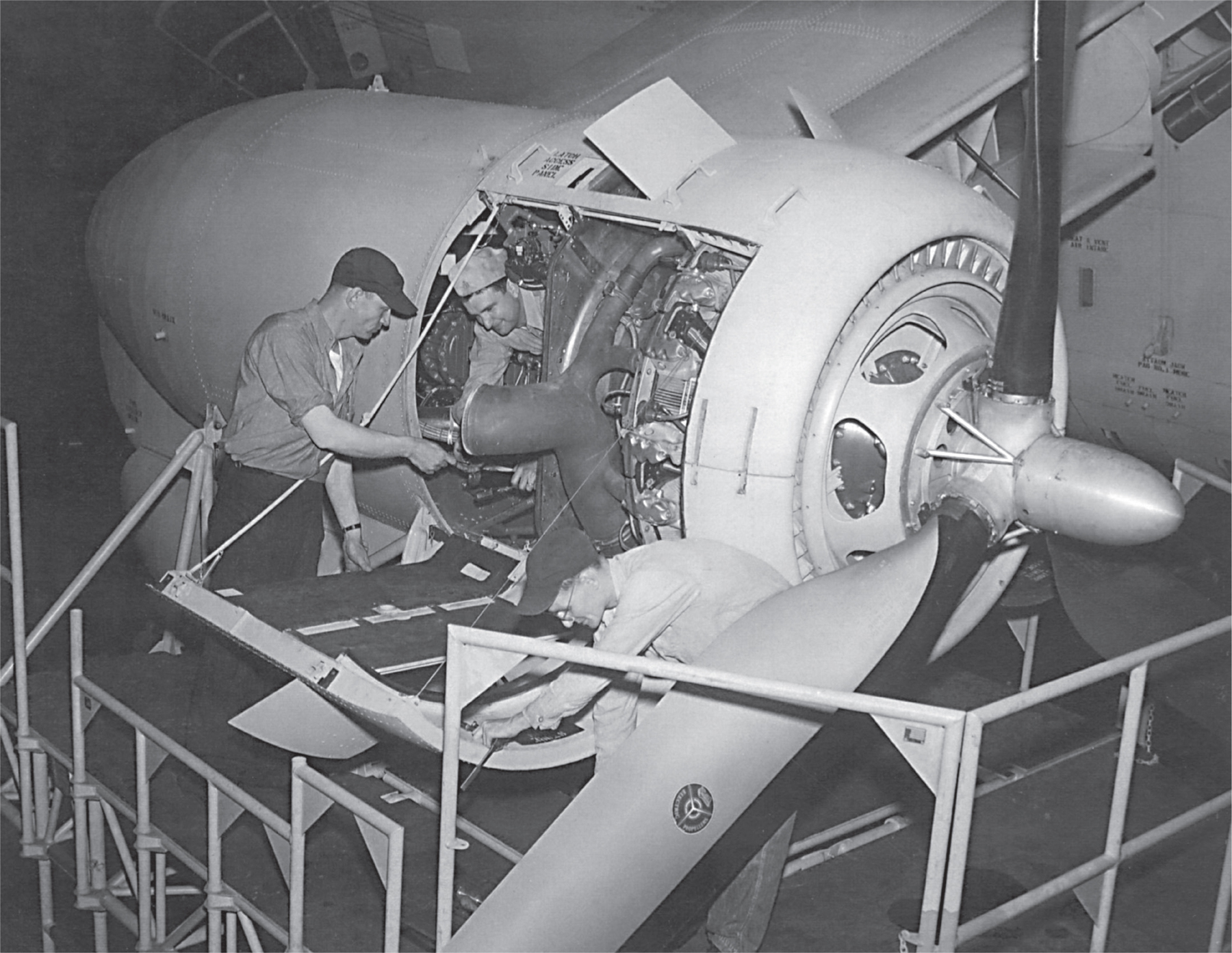

In 1947 the M-type nonrigid was the largest airship in the world. But BuAer had initiated a design competition that May for a larger, long-endurance ASW vehicle. On 18 May 1948, a contract was signed with Goodyear Aircraft for the new ship. Prototype specs called for an envelope 324 feet long with an envelope capacity of 875,000 cubic feet. As the design engineering evolved, a number of innovations were incorporated, including a two-deck control car. Off duty, crewmen could mess and bunk on the upper deck—a refreshing physical and psychological remove from all the working spaces on the lower deck. The familiar mechanics panel was eliminated and, as well, all engine instruments moved forward to the pilot’s compartment: a roomy Plexiglas-enclosed flight deck at the forward end of the eighty-three-foot-long car. A large radar radome was hung below the control car. The N-1 would be powered by two air-cooled Wright R-1300-2 engines rated at eight hundred horsepower each. Their location, however, was the most novel feature of the new model. Both power plants were mounted inside the car instead of outboard. As a result, the engines were readily accessible for in-flight maintenance and repair. Two reversible-pitch propellers were mounted on outriggers, with only small-diameter nacelles to accommodate the propeller hub and gearbox—a feature that enhanced streamlining. This singular aircraft was designed specifically for one-engine operation for optimum fuel economy. Using interconnecting clutches and transmissions, either engine could drive both propellers.

Another new feature of the prototype was an X-type empennage. Four ruddervators, which combined the functions of rudders and elevators, were moved to a forty-five-degree position about the stern to facilitate heavy takeoffs.1 Retractable, tricycle-type landing gear was yet another innovation, one which had been tested and approved by CNATE on the M-2 in 1947.

A mock-up of N-1 was completed at the Goodyear plant and ready for Navy inspection early in 1949. The CNATE command found it “impressive.” But a number of engineering problems nagged the prototype. The power-transmission system, heretofore untried, proved especially troublesome. The fin design, ballonets, the new neoprene-coated rayon envelope, and the ship’s control system all generated problems for the engineers. ZPN-1 did not make its inaugural flight at Akron until 18 June 1951. Further tests and improvements were needed before the ship was ferried to Navy Lakehurst, where N-1 landed on 17 June 1952 after an uneventful delivery. The Navy’s preliminary evaluation of the new ship began in July. Performance was something of a disappointment, so added tests to explore specific improvements were necessary.

General arrangement of ZPG-2. Capabilities included the latest search systems adaptable to aircraft: best ASW radar extent, Loran, sonobuoys, MAD, and other sensors. Unique to LTA is the variable-depth towed sonar. In the first nonrigid with two decks, berthing and messing were topside—a short physical yet refreshing remove from the operating and ASW gear on the lower. Goodyear Aircraft Corporation

The new ship brought her teething problems to a busy naval air station. By June 1952 station complement had climbed from a postwar low to just under 3,750 naval and civilian personnel, including 229 officers. NAS Lakehurst was providing housekeeping and logistic support for two fleet squadrons: ZP-3 and Helicopter Utility Squadron 2, which had arrived in 1947. Also aboard were three LTA reserve squadrons, or “Weekend Warriors,” the Aerographers’ and Parachute Riggers’ Schools of the Naval Air Technical Training Unit, and a detachment of Marines. The Overhaul and Repair Department was handling major work for all airship models and for several helicopters types. The helium plant was supporting the requirements of LTA and other activities in need of helium. The Airship Training Center (established that March), had consolidated all training. And the CNATE command was engaged with tests and various experimental projects.

Airship Squadron Three (ZP-3) was an operational unit of the Atlantic Fleet. The squadron was manned by 282 officers and enlisted personnel, with five aircraft assigned. The entire program at this time—ASW, training, experimental, and R&D—comprised three dozen blimps operating from seven bases. Except for a single reserve unit divided between Oakland and Santa Ana, all LTA operations were confined to the Atlantic Coast.

Aircraft assigned to Helicopter Utility Squadron Two (HU-2), Hangar No. 3 Lakehurst. Helicopter Development Squadron VX-3 was first to arrive, in 1946. Units of the Atlantic Fleet, the two helo squadrons exemplified the diversity of station functions following the Second World War. C. E. Rosendahl Collection, HOAC/University of Texas

A K-ship strains against men on the handrails, about 1950. Capt. F. N. Klein Jr., USN (Ret.)

A variety of airships were operating. The older L- and G-ships were still in service, as were the standard ZPK, the modernized ZP2K and ZP3K versions, the XM-1, and the M-2, M-3, and M-4.2 The prototype N-1 was undergoing flight tests. As well, nonfleet activities underscore the variety of Lakehurst’s responsibilities in the early 1950s. In the six months between January and June 1952, the Airship Training Center had flown five airships 1,300 hours. The Experimental Center logged another 389 hours aloft. The Operations Department’s six airplanes had flown nearly 1,000 hours. Test drops of dye markers had been made for the Bureau of Ordnance. A final report was submitted on in-flight engine accessibility of the ZP2K, and radar interference was investigated for the same model. A Coast Guard detachment had been trained and equipped for special duty involving barrage balloons to assist Voice of America broadcasts. Weight distribution on the M-3 also had been investigated and preliminary flight tests conducted of a limited airborne Combat Information Center—the first use of an airship as a Distant Early Warning (DEW) system. In fall 1951, ZP2K-85 assisted the Bureau of Ordnance in the development of air stabilizing accessories for its Mark 43-0 and 43-1 torpedoes.

In short, the skies over Lakehurst were busy with helicopters, blimps, and airplanes. NAS Lakehurst in 1952 was the oldest and largest LTA base. Now a vigorous construction program again was under way. Landing mats were extended to increase the area available for airships. Landing strips were cut through the scrub pine to accommodate larger airplanes. Additional helium storage was constructed. The station celebrated Armed Forces Day on 17 May with five thousand visitors. In June, the newly commissioned passenger liner SS United States received an airship escort. Finally, a sign of the Cold War and its preoccupations, a statewide air raid drill was held. All personnel had to proceed to an assigned “trench area” as part of the exercise.

Lighter-than-air training continued to intensify. The first postwar class had convened in 1946. Now, during the first half of 1952, four classes totaling fifty-one students had been graduated as naval aviators (airship), with another fifty students (nonpilot). Over the next five years approximately five hundred aviators would graduate before all LTA training was discontinued in 1959.

Prior to and throughout the Second World War, the LTA training program had been distinct from HTA. That is, airship pilots were trained only in blimps. In 1947, however, LTA was integrated into the overall naval aviation organization. All pilots with the rank of commander and below were now sent through heavier-than-air flight training as well. Airship men began to arrive at Pensacola. Lakehurst, for its part, closely monitored the progress of its aviators.

Beginning in 1948, all new LTA pilots were qualified HTA aviators who had been given a four-month transitional course followed by a two-year fleet tour of LTA duty. The course included two weeks of ground school on the design and construction of airships, their controls, and the aerostatics and aerodynamics of lighter-than-air flight. Electronics, meteorology, navigation, and the essentials of ASW also were covered. Free balloon training was part of the syllabus and was, as always, a popular component of the program. Nonetheless, the expense of the helium lost “overboard” was becoming increasingly unacceptable. Free balloon time was reduced, except for some primary and occasional refresher training. By 1958, free balloons were no longer a regular part of the curriculum.

The airship requires a skillful combination of conventional airplane handling and the science of ballooning. The heavier-than-air pilot found that the controls resembled those of an airplane except that no ailerons were required, and there were two control wheels. (With the introduction of the ZPG-2, the necessity for two pilots to operate the ship and the familiar rudder wheel were eliminated.) Formerly, one pilot controlled both rudders and elevators alone or, in cooperation with his copilot, divided the responsibility for altitude and direction control. In contrast, the N-class and later models had their controls combined through the single column, duplicated at each seat, that could be operated manually or automatically. Standard aircraft instruments provided flight and engine performance information for the pilot, with duplicate instruments as needed for copilot and navigator. There were, however, additional instruments peculiar to lighter-than-air: superheat and ballonet fullness indicators and a helium low-pressure warning system. A Sperry Autopilot was installed for automatic flight control, greatly improving stability over earlier models and reducing the airship’s tendency to “porpoise.” Trim and pressure were controlled by adjusting the volume of air in the internal ballonets in response to temperature and pressure variations. These fabric compartments were analogous to trim tanks on submarines: more air forward made the ship nose heavy; more air aft caused the tail to drop. The most difficult adjustment for the novice HTA aviator was the airship’s relatively slow or “mushy” response to the controls.

Under specific conditions, airships are literally lighter-than-air.3 For flight operations, however, the aircraft were normally loaded heavy and made a rolling takeoff similar to an airplane’s. Takeoff speeds were a leisurely twenty to thirty knots, depending on heaviness. Cruising speed was about forty-five knots. Once under way, most of the ship’s weight and payload was supported by the static lift within the envelope. This resulted in unusual fuel economy for an aircraft, since a relatively small portion of engine power was required for dynamic lift, the balance being available for forward speed. A maximum speed up to seventy knots was sustainable with the N-type for short intervals, but it was more economical to use a cruising speed consistent with mission. Flights of several days’ duration were practicable. The crew usually rotated on long flights, four hours on watch, four hours off.

Flight deck of the ZPG-2/2W. The flight engineer’s panel (K-type) was eliminated. All standard instruments for in-flight information and engine performance now were ceded to the pilot, with duplicate instruments for copilot and aft for ship’s navigator. USN

Under way, the pilot could adjust his heaviness by a gain or loss of seawater ballast. Helium could (of course) be valved to reduce static lightness. A normal landing was made about two hundred to four hundred pounds heavy, the aircraft touching down and rolling out toward the ground crew with power just ample for control. Once well in hand, the ship was hauled in to a mobile mast, then shunted to a mooring circle or towed to hangar berth.

The 1951–53 flight trials of the ZPN-1 highlighted the need for a number of design improvements. These were incorporated into the production ships, designated ZP2N-1 (ZPG-2). The most notable changes were a larger envelope to accommodate heavier electronics and armament loads and improved radar gear. The first production version flew at Akron on 1 April 1953. As finally configured, the Nan ship had a length of 343 feet and a height of 97 feet, with an envelope volume of 1,011,000 cubic feet. Normal crew complement was fourteen. Cruising speed was forty-five knots with a fifty-five-hour endurance at forty knots. The first production ship reached Lakehurst on 6 October 1953; another two arrived by year’s end. The first fully equipped ZPG-2 was delivered from the factory in July 1954. Three aircraft reached the Navy in 1954, one in 1955, and the final allotment of four in 1956. Total procurement costs for twelve aircraft was $64.5 million.

NAS South Weymouth, MA. Following extended trials, the first fully equipped ZPG-2 was delivered to the fleet in July 1954. Assigned for all-weather tests (emphasizing winter), here two pass in formation. Equipped with sophisticated electronic and detection gear, cabin spaces were a stable, vibration-free platform hospitable to equipment and crew, particularly on extended searches. H. J. Applegate

The ZPG-2 ASW airship of the 1950s was a formidable weapon system. Its gross lift (static plus dynamic lift, approximately 64,500 pounds) allowed a full range of electronic capability. The aircraft was crammed with an array of highly classified electronics and detection equipment. Generous cabin spaces provided ample room for plotting and control facilities. Moreover, its stable, vibration-free environment and relatively slow speed were ideal for the sophisticated, delicate electronic gear essential to its military mission. And the airship’s size and low noise levels provided a hospitable, relatively comfortable in-flight environment for the crew, particularly on extended searches.

Testing continued through the 1950s. Early in 1955, for example, the research and development unit at NAS Key West, ZX-11, began extended operational trials while a second ship was flown to the Naval Air Development Unit (NADU) at South Weymouth for intensive all-weather tests, emphasizing winter operations. But it remained to be seen how the surface fleet would make use of the platform.

The endurance capability of this singular aircraft was verified in a spectacular demonstration. BUNO 126716, the first production ship to reach Lakehurst, arrived in October 1953 to begin its trials for acceptance. Chief staff officer for CNATE at this time was Cdr. M. H. Eppes, USN. Many local test flights were logged and, as data accumulated, it appeared possible to increase endurance well beyond that guaranteed by Goodyear. The idea of a maximum endurance flight was born.

After an abortive try in April 1954, which had the ship in the air for 77.1 hours, ZPG-2 BUNO 126716 departed Lakehurst at 0632, 17 May 1954, with a crew of fourteen. Eppes was in command. Altogether, 15,800 pounds (about 2,650 gallons) of fuel were aboard. The ship’s flight track took “716” northeast to Cape Cod, then slowly south over the Atlantic, past Bermuda toward Puerto Rico and the Caribbean—finally island hopping northwest to Florida. Fuel consumption, a critical factor throughout the flight, was reduced to a minimum by using one engine for sustained periods, throttled back, the mixture leaned out for optimum economy.

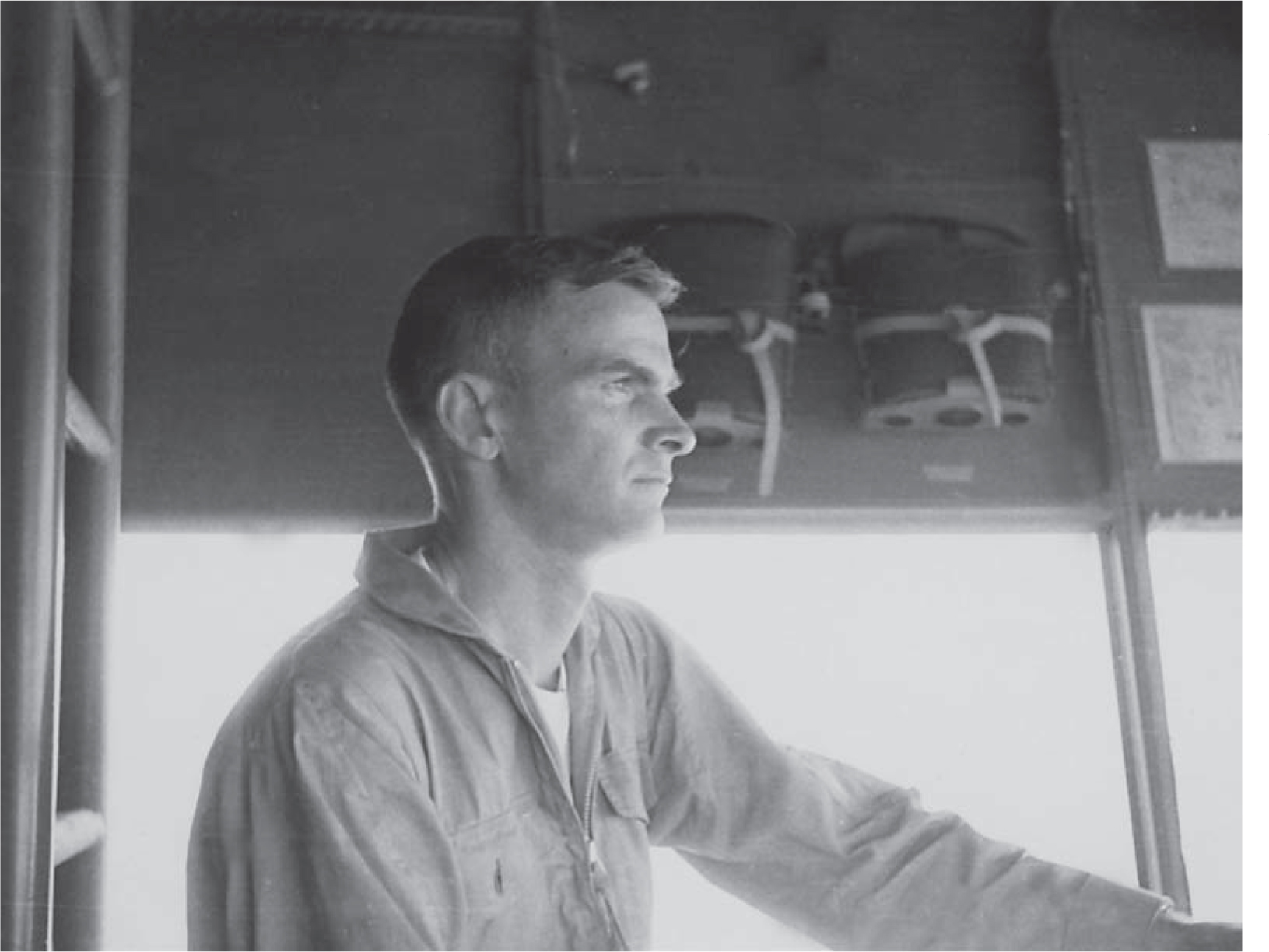

Cdr. M. H. Eppes, command pilot, at the controls BUNO 126716, 17–25 May 1954. BIS trials had suggested an unusual endurance capability for the ZPG-2. Fuel economy—a critical factor—was adroitly exploited (as low as 42 pounds/hour), thus granting a new record for self-sustained flight: 200.2 unrefueled hours. In March 1957 the achievement would be bested by another N-ship. E. L. Moore

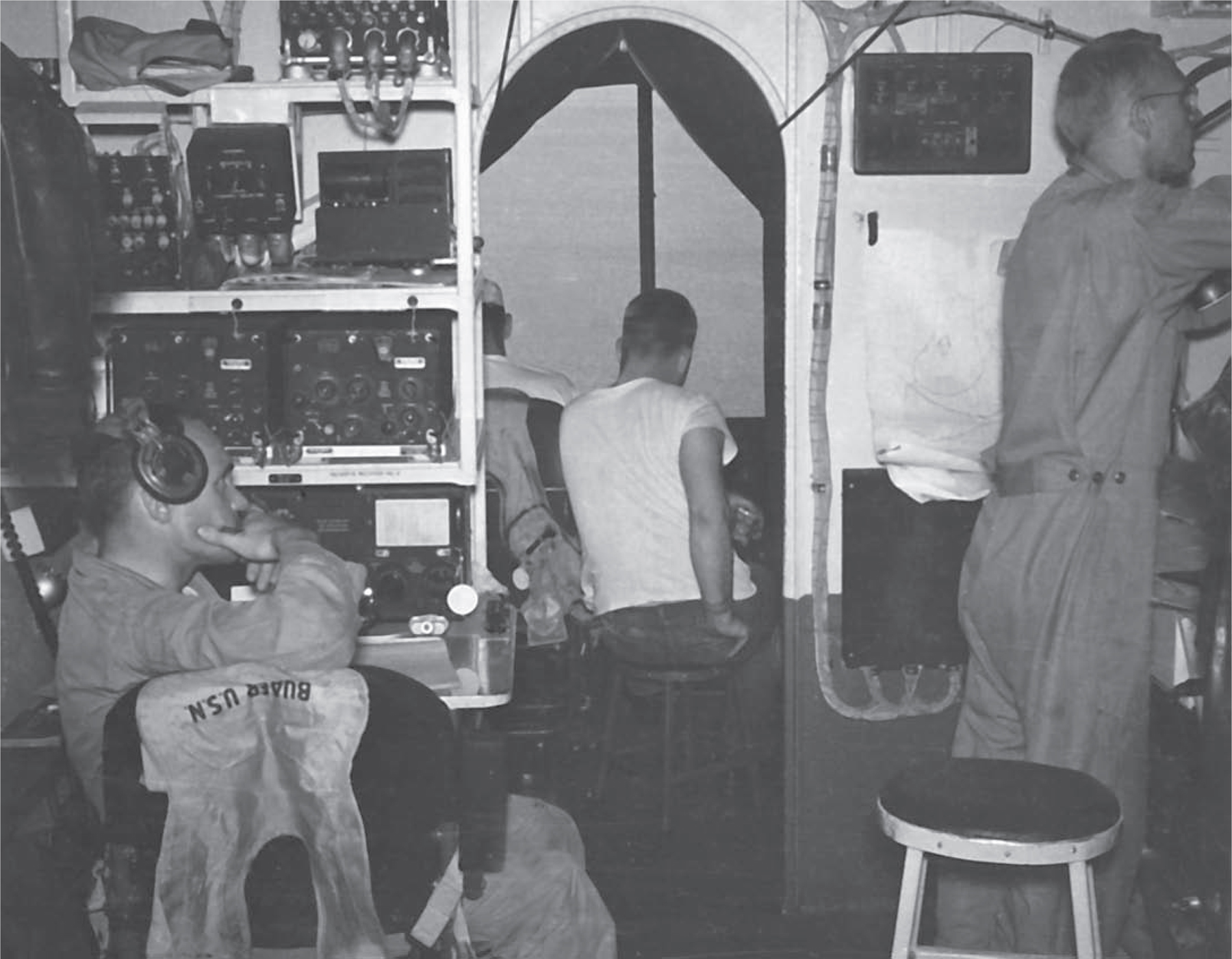

View forward from the ASW compartment into the cockpit of “716,” somewhere over the Atlantic. Chief Paul G. Richter (left) is on watch “manning the circuit” at the radio operator’s station; Chief William P. Koll is fussing with the temperamental Loran at the navigator’s station. ATC P. G. Richter, USN (Ret.)

On 25 May, at 1436, the airship touched down at NAS Key West to a rousing welcome. Official flight time: 200.20 unrefueled hours in the air, or 8.3 days. Photographs, speeches, a press conference, and telegrams of congratulations followed. Commander Eppes was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and, in 1955, the Harmon International Trophy for Aeronauts, presented by Vice President Richard M. Nixon. Each crewman was awarded the Air Medal.

In 1957, this astonishing performance was exceeded by another ZPG-2. Departing South Weymouth on 4 March, Cdr. Jack R. Hunt, USN, in command, BUNO 141561, nicknamed “Snowbird,” completed a transatlantic circuit east to Europe, thence Africa and back across to North America at NAS Key West, a distance of 8,216 miles without refueling. This eclipsed the distance record set by Graf Zeppelin between Friedrichshafen and Tokyo in 1929 and established a longstanding world record for sustained, unrefueled flight by any type of aircraft—264.20 hours aloft (11 days).

Lt. Stanley W. Dunton at the navigator’s station, ZPG-2 BUNO 141561, during the 1957 record-endurance flight, 4–15 March 1957. Note flight gear, Loran chart, and navigator’s instruments. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

“561” over Miami, 15 March 1957, en route to NAS Key West. Command pilot Cdr. Jack R. Hunt and his crew are about to establish an unrefueled endurance record of 264:20 hours—eleven days aloft. As well, a new distance record was set: 9,448 nautical miles. Having more critics than supporters (and never mind capabilities), reductions in LTA forces are imminent. K. Pace

An advertisement by Goodyear, 1957. Goodyear Aircraft Corporation

The N-ship was becoming the primary LTA platform of the 1950s, but it was not the Navy’s only airship. Thanks to modernizations, the K-ship was still providing excellent service. The type would endure until 1959. In August 1950, the first postwar modification, the ZP2K-1 (redesignated ZSG-2), was delivered. Envelope volume was now 456,000 cubic feet for all units and the control car thoroughly modernized. Major improvements included the installation of a sonobuoy receiver, upgraded radio and radar gear, and provision of an automatic pilot. The airship was equipped for in-flight refueling and for taking on water ballast at sea. The normal flight crew was six men: pilot (elevatorman) and copilot (rudderman), a radio operator, one mech, a rigger, and the navigator. Gross static lift was 27,450 pounds with a total empty weight of 21,650 pounds. Useful lift (5,800 pounds) represented nearly 21 percent of the aircraft’s gross lift.

As part of its policy of progressive modernization, in 1949–50 the Navy invited bids for a proposed ZSG-3 ASW airship. This modification called for better landing gear for carrier landings, new electronic equipment, and improved overall operational characteristics. In November 1952, the ZSG-3 was flown and accepted at Lakehurst. Essentially a ZSG-2 renovated to permit installation of new, more modern equipment, the ZSG-3 design was intended for carrier-based operations. An electric winch aft provided a hoisting and sonar towing capacity. Like its predecessor, the ZSG-3 was equipped for in-flight refueling and reballasting. Both internal and external bomb racks were carried; droppable fuel tanks also could be used for extended operations. Envelope volume was increased to 543,000 cubic feet. Thirty units were procured and nearly $13 million expended for conversion of the ZSG-2 to the ZSG-3.

Indoctrination exercises to sustain airships from carriers, here a joint operation with USS Mindoro (AKV-20), March 1950. At-sea touchdowns, deck handling, and replenishment called for skilled airmanship and a great deal of experimentation to establish and standardize techniques. Unlike carrier aviation and the hardware of a “new” nuclear Navy (and appearances to the contrary), LTA had yet to integrate into fleet forces, operations, and the naval aviation organization. DOD

The ZSG-3 was intended specifically for operations with carrier forces, one of the program’s most significant postwar developments. In a test of refueling, the first successful carrier landing by a U.S. nonrigid airship had been logged in February 1944 by K-29, attached to ZP-31 out of Santa Ana. The escort carrier Altamaha (CVHE-18) had King-29 aboard off San Diego. Six months later, in August, K-111 under the command of Lt. Cdr. F. N. Klein Jr., USN, demonstrated the feasibility of refueling and replenishing airships from carriers. During a seventy-two-hour operation, the airship’s crew was relieved every twelve hours; for one evolution, K-111 was held to the deck of the escort carrier Makassar Strait (CVU-91) for thirty-two minutes.4

These exercises were the first tentative efforts to explore the practicability of airship-carrier operations. The blimp might then be deployed with the U.S. Fleet in the western Pacific for mine spotting and for antisubmarine work against Japanese submarines, using carriers as bases. No airships were ever so deployed. But the concept of increasing an escort airship’s range and endurance was explored in the period 1945–56. The advantages were clear. Refueled, rearmed, and replenished from carriers and oilers, the blimp’s at-sea, on-station time—thus, its ASW services—could be extended. The exchange of fresh crews and minor maintenance also might be conducted at sea. In sum, feasibility and development tests were aggressively explored.

An ordnance crew secures a Mark XXIV acoustic antisubmarine homing torpedo onto an external bomb rack on a modernized K-type (ZSG-2), April 1949. A carrier could refuel, rearm, and reman airships at sea and, thus, sustain their ASW services to surface units. USN courtesy Mrs. E. P. Moccia

As one example, in January 1949 a series of operations were conducted with two squadrons of Fleet Airship Wing One that demonstrated that the airship could be safely sustained from carriers for “reasonable periods.” These exercises reached a peak during 1949–52, with the surface fleet cooperative if not to say enthusiastic. All LTA flight personnel became familiar with the intricacies of the operation—no mean effort given two craft moving independently in different elements. There were accidents, most of which involved damage to the airship from hard landings or coming into contact with some part of the carrier. By the time the last carrier landings were logged in spring 1956, each model from the ZPK through the ZS2G-1 had demonstrated its ability to land and to resupply from surface units. The introduction of the ZPG-2 ended all such exercises: the airship had become too unwieldy for safe handling on a heaving deck. The N-ship’s inboard engines, moreover, were serviceable in flight, a relief crew was aboard, and development of in-flight refueling had eliminated the need to land at sea for fuel.

Takeoff from the deck of USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVS-42), 20 June 1949. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

In-flight refueling from surface units was a major postwar development. This effort to extend the airship’s tactical range and endurance was vigorously explored in the 1950s. The first technique to be tested was the hose method: a carrier, a fleet oiler, or a destroyer exploited as “mother.” Little special equipment was required: a hose, fuel pump, reel, and storage. A winch and hoisting cable on the airship for retrieving the hose was standard gear. For pilots, maintaining station above a surface unit while refueling called for skilled airmanship. In the “alongside method” from an oiler, for example, both vessels had to maintain a heading about twenty degrees off a stiff breeze, the blimp approaching from astern to retrieve the hose when abeam of the ship’s windward side. Here it remained throughout the transfer, perhaps a hundred feet to windward of the vessel below.

In-flight fueling tests, 1951–55: here a ZSG-3 in position (alongside method) with a standard fleet type tanker. At-sea fueling, reballasting, and provisioning were major postwar developments. The enhanced capabilities of LTA had yet to be worked into the overall scheme of naval operations, nor were they destined to be. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

A “bag method” also was perfected. The airship retrieved a floating fuel cell. Sea trials between November 1958 and March 1959 demonstrated the utility of this technique. The rubberized cells could be dropped into the sea for later retrieval by a surface unit or by parachute from an airplane or airship. The receiving aircraft trolled for the bag’s line and float assembly, using its utility cable played out from the after compartment. Once intercepted, the cell was winched up through the after hatch and the transfer completed.

The final K-ship configuration was the ZSG-4. Forty million dollars were authorized for fifteen aircraft delivered between August 1954 and July 1955. Overall length was 266 feet with envelope capacity of 527,000 cubic feet. For the first time the K-type was fitted with a flight-control system for either dual rudder and elevator control or conventional (divided between pilot and copilot). Armament was carried in a bomb bay and on the lower outrigger struts. Ordnance could be replaced by extra fuel carried in the bomb bay and in drop tanks. The normal flight crew consisted of eight airmen: pilot and copilot, navigator, radio and sonar men, electronics-countermeasures operator, radarman, and one man for the after winch. The ZSG-3 was flown until 1955, when all were decommissioned. The ZSG-4 model would remain in service until March 1959, when the last King-ship in inventory, K-43, was retired in a brief ceremony at Lakehurst.

A wholly new ASW airship was designed and delivered in the mid-1950s: the ZS2G-1. Somewhat larger (670,000 cubic feet) than the ZSG-4, the new model was designed to provide long-endurance convoy capability and configured to carry an integrated system of ASW equipment and weapons. The singular feature of this new “blue water” aircraft was its inverted Y empennage.5 Cruising speed was forty-five knots, with a twenty-seven-hour endurance at forty knots. Flight crew consisted of five officers and six enlisted men. Refueling, reballasting, and rearming features were incorporated, including gear for towing or dipping sonar. A total of eighteen ZS2Gs were procured between 1955 and mid-1958. The first was delivered to Navy Lakehurst from the contractor on 26 May 1955.

A ZSG-4, 1957. Peace brought declining military dollars. The early 1950s saw stirrings as to rigid airships for air transportation, which came to nothing. The naval nonrigid was upgraded to augment an accelerating Cold War defense, the ZSG-2 and ZSG-3. The ZSG-4 (527,000 cubic feet) was a new airship: final configuration of the basic wartime patrol platform. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

ZS2G-1 landing at Akron. Note the inverted “Y” control system. This model—“a little bit of a dog”—was intended to replace the K-type, a “blue water” ship for ASW and operations with carriers. Eighteen were delivered during 1950–58. Its operational history proved brief; by March 1960, all but one was in “live storage.” U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

The operational life of the ZS2G-1 aircraft was brief, all but one placed into war-reserve storage in spring 1959. The lone ship remained in service until program termination in 1961.

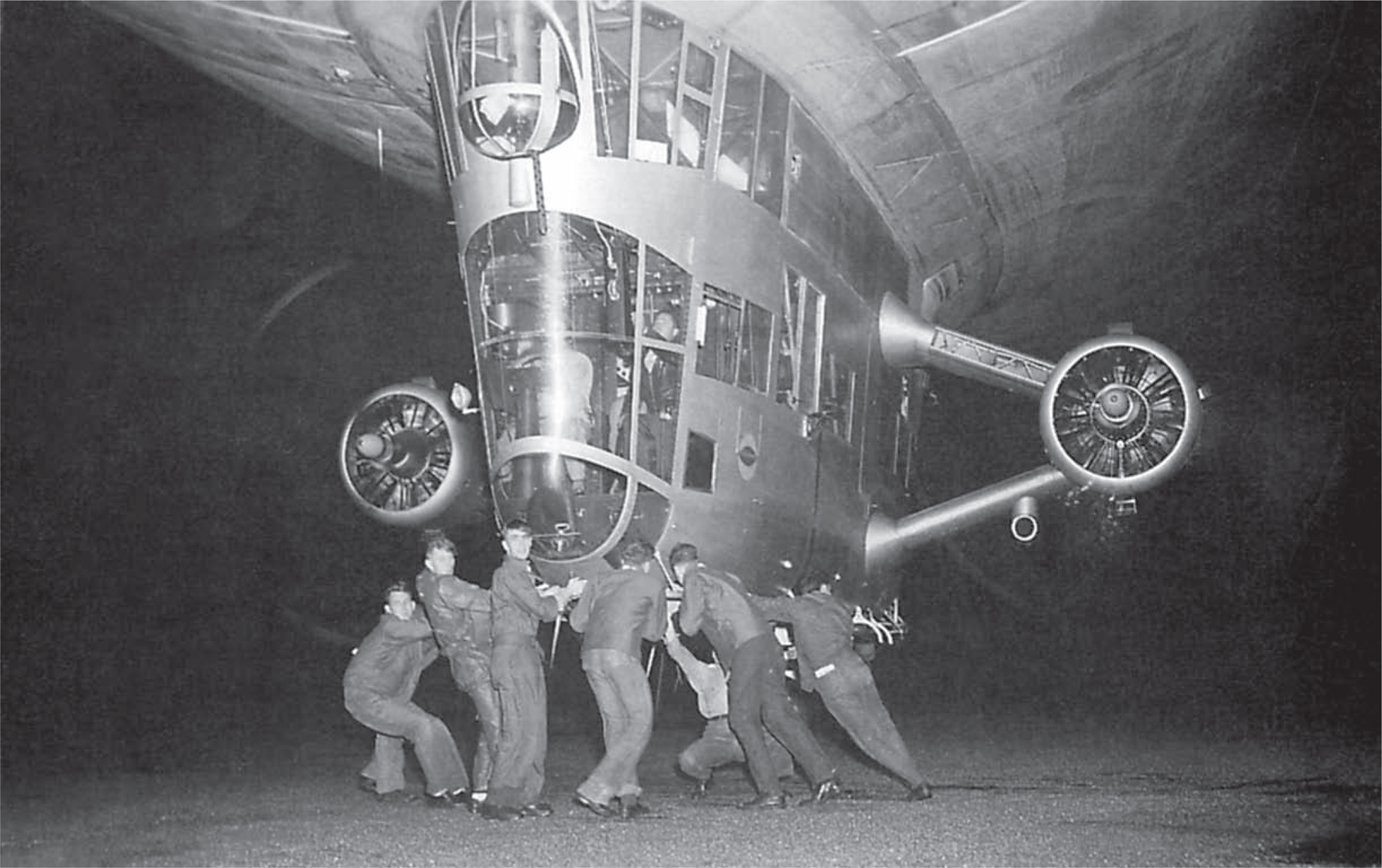

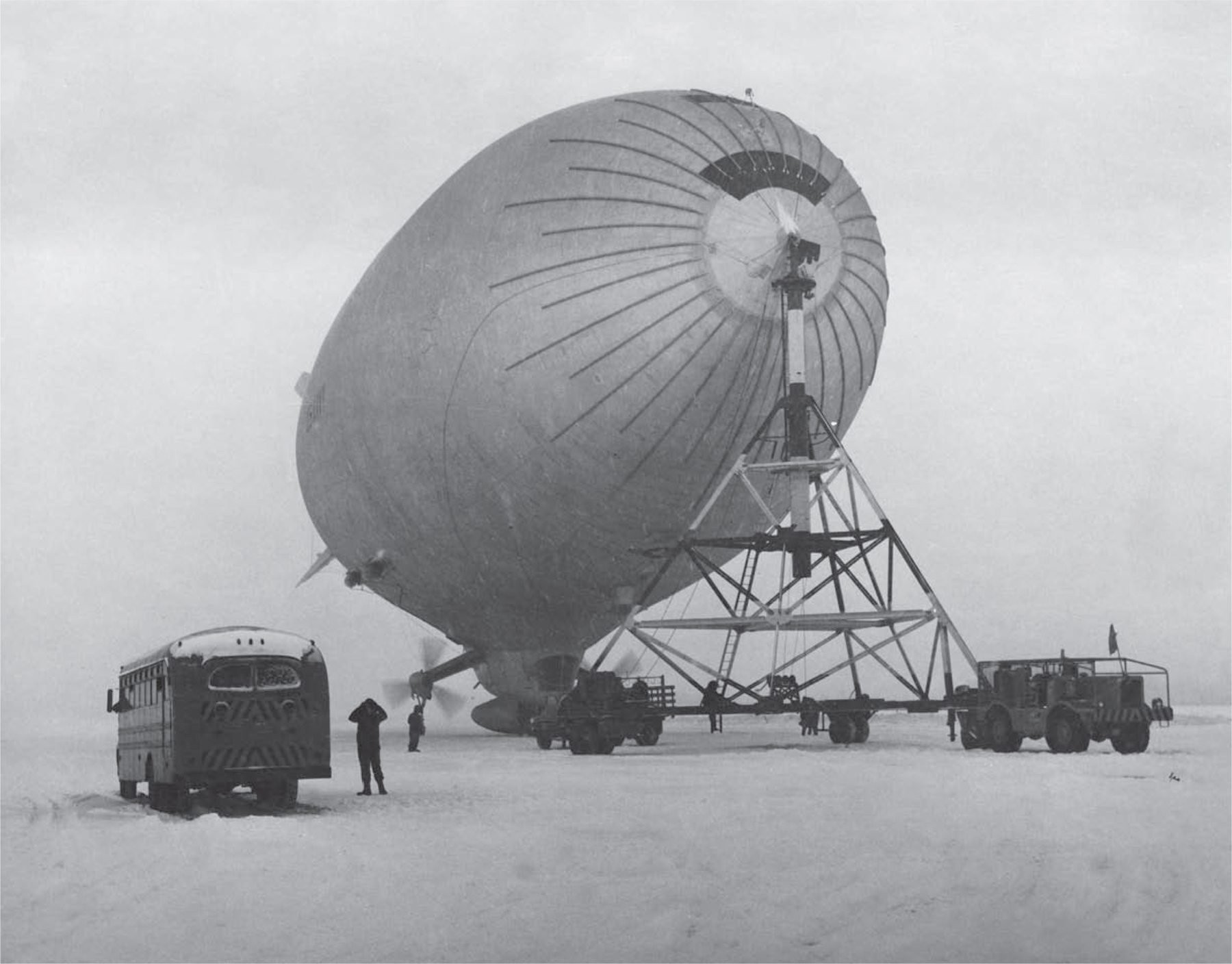

In brief, the years 1945–60 were remarkably fruitful in terms of technological advances and hence capability. Not all progress involved the aircraft. Mechanization of ground handling experienced a virtual revolution in this interval. The mobile mooring mast was brought to a high state of refinement. And because of the ships’ increased size, masts grew larger and more complex. The Type V mast, introduced with the ZPG-3W in the late 1950s, weighed nearly 129,000 pounds and carried its own power unit. Thus, the mast could now supply electricity to the airship for lights, heaters, blowers, power to start the engines, and supply its own requirements. Despite its size, the Type V could be disassembled for transport. And air-transportable aluminum stick masts—supported by steel cables and anchors—were so designed that sections could be added or removed to accommodate whatever class of ship was assigned to expeditionary sites.

The introduction of mobile winches, or “mules,” was a fundamental advance. These vehicles held ships’ yaw lines and maneuvered to keep them steady when off the mast. Mechanical mules simplified ground-handling, enhanced safety, and reduced the large teams of men on the lines. Airship ground handling had become an intricate and demanding operation, especially during docking and undocking, masting and unmasting, taxiing, and mooring out. By 1961, the Handbook of Airship Ground Handling Instructions, issued by the Bureau of Weapons, had grown to fifty-odd pages of well-worn operational experience.

Type V mooring mast—the program’s largest. The power cables provide electricity for ship’s lights, heaters, blowers, and for power to start the two Wright Cyclone engines. The tilting assembly allowed the airship to kite while secured. USN courtesy Mrs. E. P. Moccia

During January 1957 Lakehurst and the NADU command (South Weymouth) flew a joint all-weather barrier for ONR. Here BUNO 141561 readies for takeoff. Rotating seaward, LTA held station for ten consecutive days in unusually severe winter weather. Note the ground-handling mule, “the best thing since reverse-pitch propellers—even better.” Crew: driver and winch operator. Capt. H. B. Van Gorder, USN (Ret.)

Technical advances did not end here. Modern antisubmarine ordnance was adapted to the platform and refinements in ASW tactics worked out and practiced, including the use of towed sonar—a particularly effective aerial ASW tool. This equipment multiplied the airship’s overall potential as a submarine detector. Quantum improvements also were made in electronic detection and identification equipment, all of which enhanced military effectiveness. The airship’s unique characteristics—endurance, large lift, advanced communications, excellent radar performance, and overall operating economy—produced a new mission for the military airship in the unsettled international environment of the 1950s: Airborne Early Warning (AEW).

AEW was a product of the nuclear age and Cold War tensions. The atomic monopoly enjoyed by the United States in 1945 was shattered only four years later when, in August 1949, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. The impact on American public opinion and on national policy was profound. The military resolve of both countries hardened. Defense spending escalated, and development of a thermonuclear weapon was made a priority by both sides. By the early 1950s the increased speed and range of Soviet bombers and the nascent threat from the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) had made the problem of defending the United States one of utmost national priority.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was plainly worried by the global potential of modern weaponry and the growing danger of surprise attack. In 1954, some of the nation’s best minds were enlisted to study the technological facets of a new Cold War problem: preventing an atomic-age Pearl Harbor. James R. Killian Jr. was named to head a Technological Capabilities Panel (TCP) to make recommendations to the president and the National Security Council relative to military technology. What has come to be known as the Killian Report dictated to a large degree the course of American military preparedness through the 1950s.

The Killian panel believed that the United States was vulnerable to surprise attack. This danger resulted from the lack of a reliable early warning system, an inadequate air defense, and a growing Soviet long-range bomber force. Upgraded air defenses were deemed vital. These would have to be in place, moreover, before new Soviet bombers and missiles became operational later in the decade. The report called for an increase in the quantity of defensive weapons and a vigorous commitment to a continental defense system against both the ICBM and the long-range bomber. In sum, the immediate threat was the manned bomber. Missiles were on the horizon but not yet a significant threat to North America.

An early warning line cutting across all possible bomber approach routes to the continental United States was recommended, including rapid construction of a DEW line across the Arctic approaches to North America. One component of this radar net would consist of “seaward extensions” of a defensive line out over both the Atlantic and Pacific, providing maximum warning of impending attack and tracking information upon which to base deployment of defensive forces.

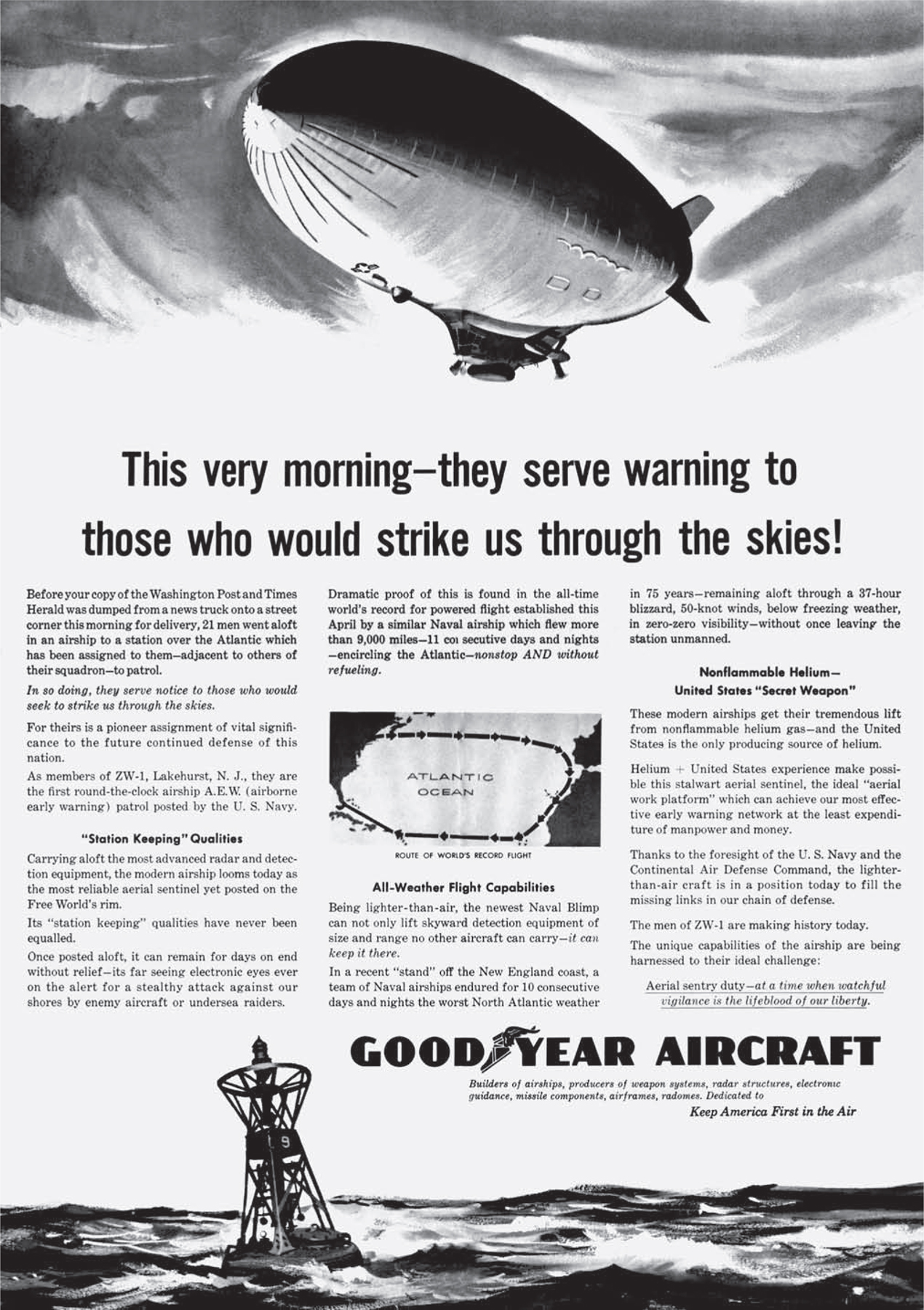

Thus, the Navy was a partner in the overall aerial defense of the continent. The LTA component of the operational plan envisaged one base for AEW airships on each coast. The inaugural AEW squadron, ZW-1, was commissioned at Lakehurst in January 1956. One year later, in February 1957, the U.S. Air Force announced that an AEW blimp squadron would go into service over the Pacific. But a second squadron was never commissioned.

The AEW airship had had its genesis during the Second World War. When radar was installed, it was discovered that the airship was an ideal aerial platform for the equipment. Compared to airplanes, the blimp represented a stable and vibration-free environment in which radar appeared to provide a consistently superior performance. Since aerodynamic shape was relatively unimportant for the airship, experimentation was conducted using antennas much larger than conventional aircraft could carry. Early results proved encouraging.

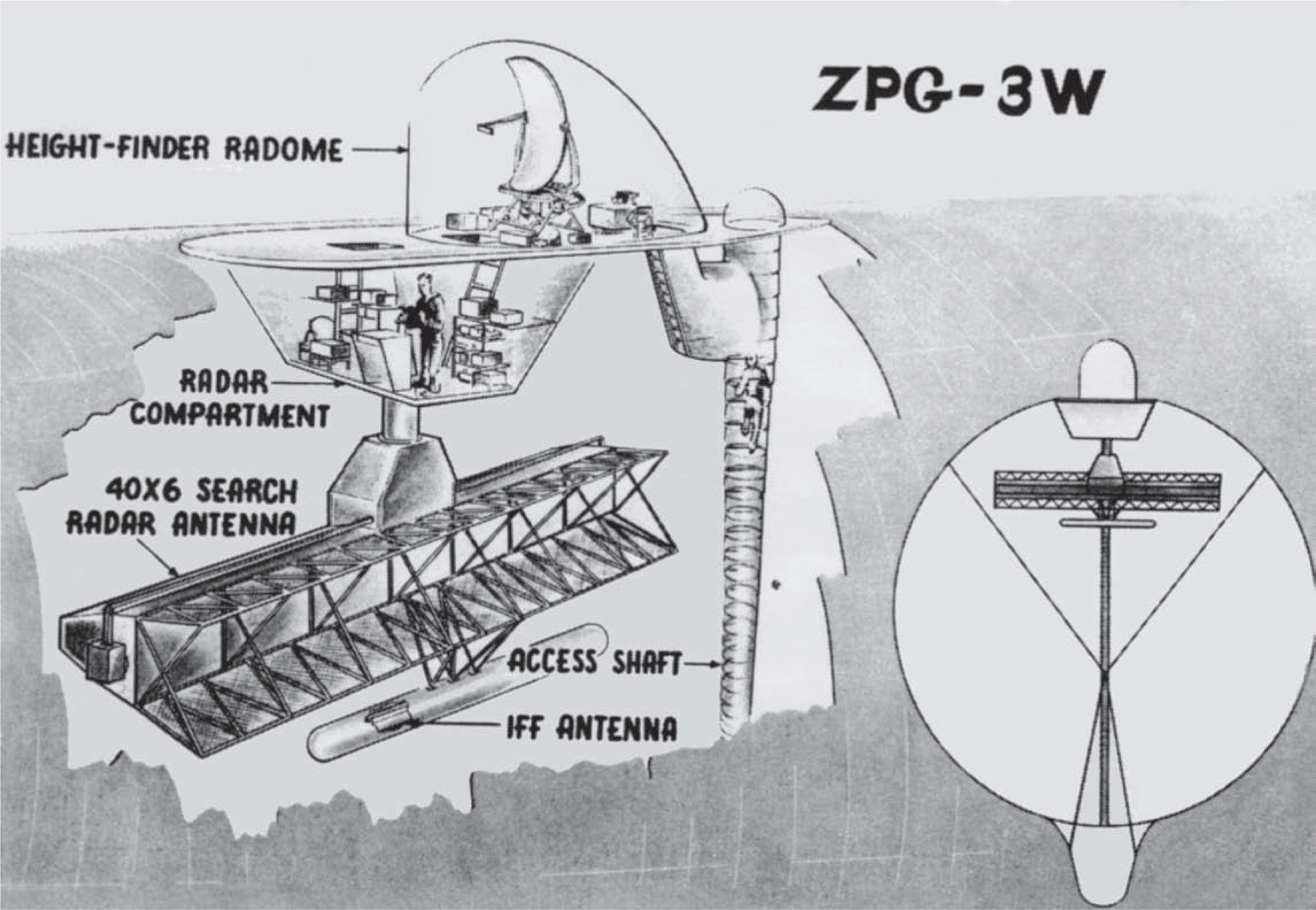

The basic AEW vehicle that emerged in the 1950s was the ZPG-2W. A modification of the ZPG ASW configuration, the “2W” was essentially the same aircraft, with structural changes limited to those essential to the new AEW electronics. Length, envelope volume, and power plant were identical. Static lift of the new ship was 60,400 pounds; gross lift was 66,400 pounds. Given an empty weight of 47,608 pounds, the ZPG-2W had a useful lift of nearly 19,000 pounds–9.5 tons. Maximum speed of the aircraft was 68.5 knots. The distinguishing features of the design were the height-finder radome atop the envelope and an oversized antenna mounted in a radome below the control car.6 The topside radome was reached via a vertical access shaft through the envelope from the control car.

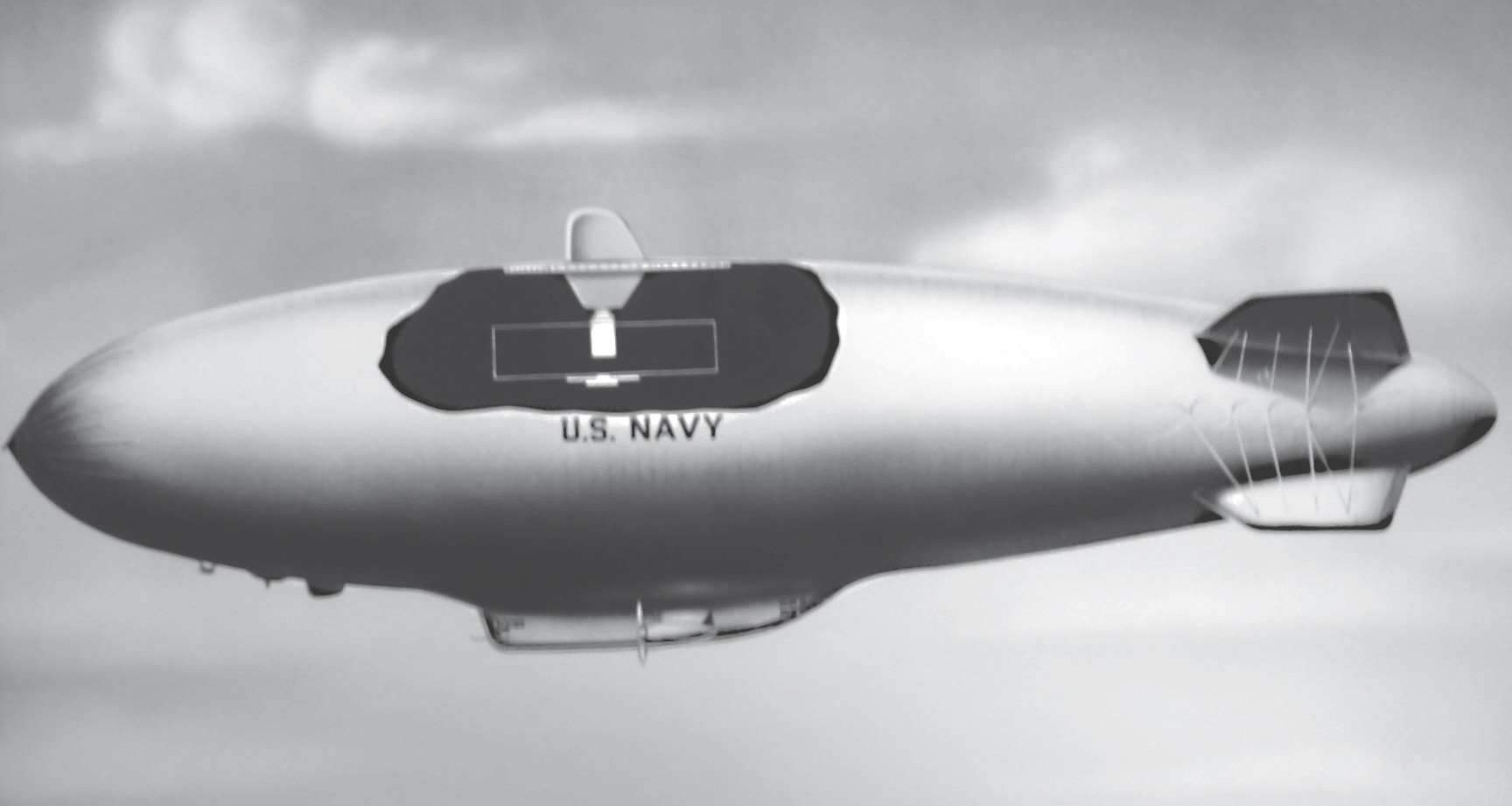

ZPG-2W. A modification of the ZPG-2, its structural changes were limited to those essential to the electronics suite and, topside, height-finder radar. When the Navy committed to seaward extensions of the continental network, Airborne Early Warning Squadron One (ZW-1) was commissioned—unique in the North American Defense Command. Operational in July 1957, ZW-1 provided sustained radar surveillance to seaward. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

The first 2W was delivered to Lakehurst on 26 May 1955. A second reached the station that December, another two in 1956, and the fifth aircraft in May 1957. Total procurement cost for five commissioned ships was $23.5 million. Each flight crew consisted of thirteen officers and men, the AEW crew of eight personnel. The twenty-one-man crew was divided into two groups, each with a separate but interconnected communications system. Height-finder gear automatically transmitted the target altitude to the search operators, who were also receiving range and bearing data displayed on radar consoles and plotting boards. In effect, the airship was an airborne tactical control center capable of directing fighter interceptors to enemy targets.

The electronic suite on board the ZPG-2W was substantially the same as that installed in AEW planes of the period. But the airship offered proven reliability, superior on-station endurance, and a relatively large combat information center, or CIC—among the best working conditions in a military aircraft. Operational costs also were favorable. A 1956 estimate indicated that maintaining an AEW airship on radar barrier cost from one-half to one-third the total cost of an airplane on the same station.

Fleet Week at Hampton Roads, 12 June 1957. USN/U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Airship Airborne Early Warning Squadron One (ZW-1) was commissioned on 3 January 1956 at Lakehurst, the first LTA squadron of its kind. In July 1957, the unit became operational. The commanding officer was responsible initially for a nucleus crew of eight officers and forty-five enlisted personnel; however, the squadron would grow to more than eighty officers and three hundred men by 1960.

Furthermore, a wholly new AEW airship was under construction: the ZPG-3W. A redesign of the 2W aircraft, the new model was structurally very similar. The “3W” was 60 feet longer (403 feet) and had an envelope volume of 1,516,000 cubic feet—the largest nonrigid airship yet built. Its lift permitted a greatly improved AEW installation, nearly twelve thousand pounds of sophisticated electronics. And mounted within the envelope was a forty-foot revolving radar search antenna, the largest antenna ever airborne. The finder radome was mounted topside, as in the 2W, the radome below the control car eliminated. Two Wright Cyclone 1,275 horsepower engines drove three-bladed, reversible, full feathering propellers, which gave a cruising speed of forty-five knots. Crew complement totaled ten officers and fifteen enlisted men. With projected in-flight endurance of sixty-nine hours at thirty-five knots, it began to appear that the reliability of the electronic gear and the physical tolerance of the flight crew might become the limiting factor in defining the overall endurance of the modern lighter-than-air platform.

Navy mechanics inside engine nacelle of a ZPG-3W, May 1959, during Navy Preliminary Evaluation (NPE), Goodyear Airdock. Cdr. R. W. Widdicombe, USN (Ret.)

The mock-up of the ZPG-3W was completed by the end of 1955, but the first ship did not fly until 21 July 1958. There were repeated delays with the 3W development program and efforts made to cancel the aircraft. Finally, on 19 June 1959, the first ship was delivered to NAS Lakehurst for preliminary evaluation. Four ZPG-3Ws were procured and commissioned at a cost of slightly more than $54 million. The final ship reached the naval air station in April 1960—the last airship accepted by the United States Navy.

The ZPG-3W was the descendent of a long series of ships beginning with the K-type designed in the middle of the 1930s. Directly, it was a vastly improved ZPG. All that had been learned by the Navy and Goodyear Aircraft on the past programs came together on this ship. All of the troublesome things were eliminated, and all of the best in improvements were incorporated. The enlargement to 1,500,000 cubic feet resulted in much greater endurance, air worthiness, and habitability. It also provided the necessary payload and space for the 42-foot internal antenna for the APS-70 radar.7

Cdr. Walter Ashe, O-in-C of Airship Test and Development (AT&D) Department, NAS Lakehurst; Lt. Cdr. R. W. Widdicombe, chief Navy test pilot for the 3W, and Walter Massic, manager of airship operations, Goodyear Aircraft, 14 May 1959. Cdr. R. W. Widdicombe, USN (Ret.)

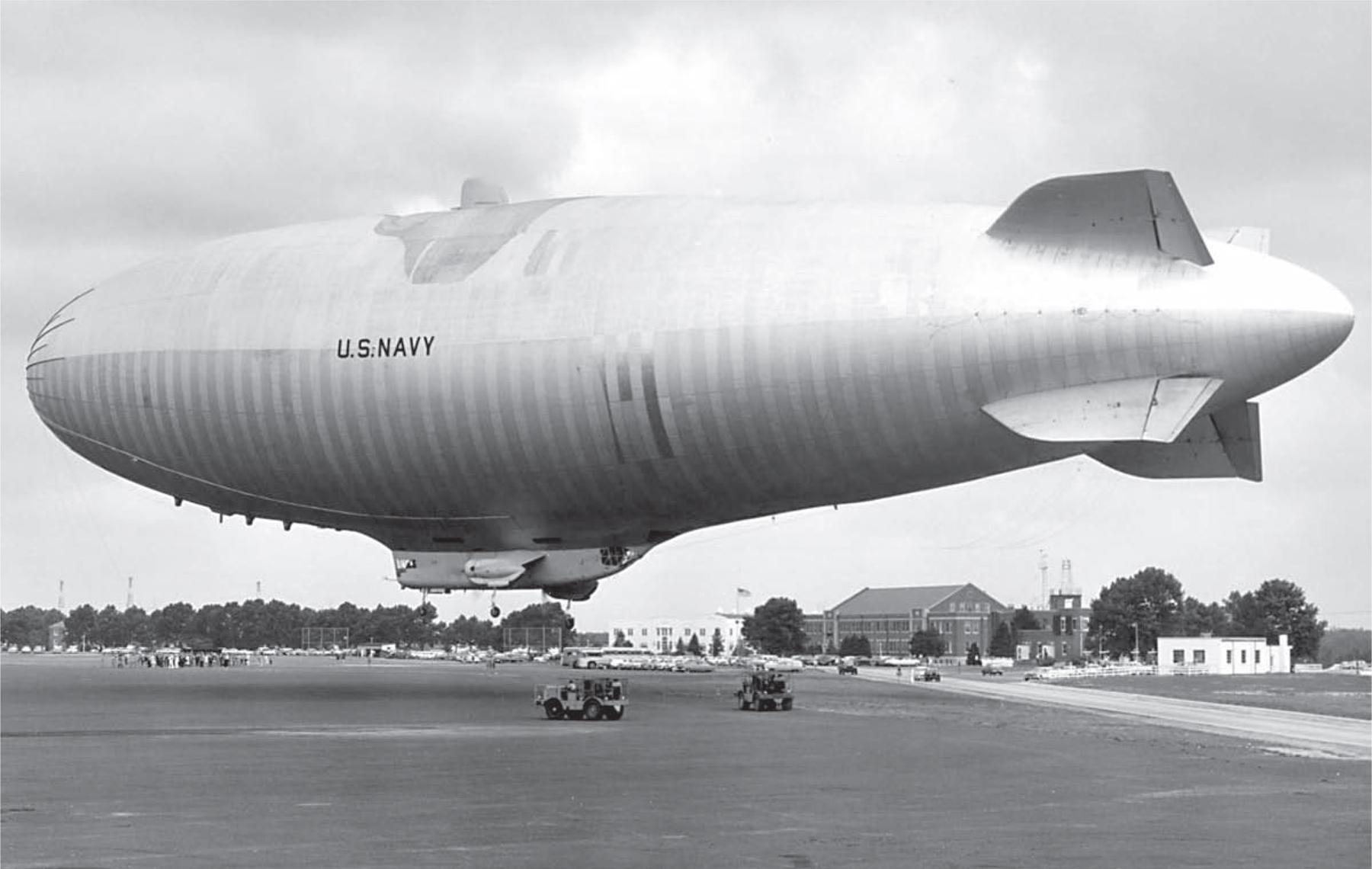

ZPG-3W at Akron, circa 1958. In general built from a new design, the aircraft had a gross weight (empty) of approximately 71,000 pounds—the largest nonrigid airship yet flown and the last LTA platform in naval service. Ground-handling mule at right. Cdr. R. W. Widdicombe, USN (Ret.)

The lighter-than-air program to all outward appearances was thriving. ZW-1 had undergone extensive training and outfitting and by June 1957 was about to become operational. A second AEW squadron was anticipated. The world’s newest and largest nonrigid airship was under construction at the Goodyear Aircraft facility in Ohio. Delivery of the first 3W was imminent. In March 1957, a ZPG-2 had captured the record for unrefueled sustained flight by any type of aircraft. Naval airship strength had reached a postwar peak of forty-four aircraft. Four fleet ASW squadrons were in commission and operational, two based at Weeksville and one squadron each at Lakehurst and Glynco. Six LTA stations were operational. Active mast facilities were available at another six stations.

The airship’s political vitality seemed to be experiencing something of a resurgence. Appearing in the spring of 1957 before a House defense subcommittee, Vice Adm. Robert B. Pirie, DCNO (Air), credited the Navy’s blimps with “remarkable endurance, great range, and unique (submarine) detection capability.” The merits of airships in airborne early warning also were acknowledged.8 Aviation Week noted that “the Navy appears to be convinced that the modern advantages of the blimp for antisubmarine warfare and radar picket duty far outweigh its vulnerability. The blimp will be an essential part of the Navy’s airpower for some time to come.”9 The popular literature also was interested and approving. These public expressions seemed to verify a belated recognition of lighter-than-air’s unique potential to modern naval warfare. An active, vital future seemed assured.

On approach, BUNO 144243 is delivered to Lakehurst, 19 June 1959, the first of four procurements. A six-month Board of Inspection and Survey and Fleet Introduction Program is about to commence. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

BUNO 144243 about to touch down, concluding a seventy-six hour test/delivery flight from Ohio. In a ceremony marking this first “3W” delivery, pilot Walter Bjerre and Goodyear Aircraft president T. A. Knowles turned ship’s log over to the air station’s commanding officer, Capt. J. R. Van Evera. USN, courtesy Cdr. C. A. Mills, USN (Ret.)

But political and military support within the naval establishment remained tenuous. The lowly blimp, its many attributes notwithstanding, had yet to be integrated into the mix of naval weaponry or into the overall command structure of the postwar Navy. Moreover, the naval service of the 1950s was preoccupied with heavier-than-air aviation. New weapons and supersonic aircraft were transforming the character of modern war at sea. In this highly technological Mach 2 environment, most officers holding a responsible position could not imagine where the blimp—slow, vulnerable, and largely defensive in capability—fit into this complex picture.

There was seemingly little the airship could do to help itself. The low number of aircraft had ensured that the airship remained an unfamiliar naval adjunct and limited the backup capability of the relatively few squadrons in commission. Similarly, the small number and geographical separation of LTA bases reduced operational flexibility. Rarely, for example, could pilots exploit rather than battle unfavorable winds. The effects of weather—high winds and freezing conditions particularly—hampered ground handling and impeded overall availability.

ZPG-3W, showing the height-finder pod and the forty-foot search antenna suspended within the envelope, hence free of aerodynamic effects. On-station virtues proved superb: comfort “excellent,” fuel economy “phenomenal,” and the outboard-engine installation “very quiet.” U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Artist’s cutaway of the ZPG-3W, topside—the world’s largest airborne radar antenna to search for, detect, and report air targets from assigned at-sea stations. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

Finally, development of the basic vehicle had been comparatively slow after 1945. In consequence, the military significance of the LTA platform remained subordinate to conventional systems with which the airship competed. This generated something of a self-fulfilling failure. Meager appropriations stunted development and deployment, which in turn retarded the growth of any real confidence in these aircraft. The resulting skepticism helped sustain a low budgetary priority. The airship’s chronic trial status in the Navy and its infrequent appearances at fleet exercises left little opportunity to refine tactics and develop reliance on its services. Indeed, by 1959 if not earlier, the airship’s participation had become something of an intrusion on established practices. For too many, skepticism had hardened into contempt, and the airship’s legitimacy was always questioned in times of fiscal uncertainty.

The military airship had reached its apogee in the U.S. Navy. In mid-1957, high-level decisions were being made to slash the program. The first of several progressive cutbacks was about to begin. In less than five years these would end the era of military lighter-than-air aeronautics in the United States.

The AEW compartment of the ZPG-3W—the last airship accepted by the United States Navy. U.S. Naval Institute photo archive