A long-range plan was launched in 1957 to end U.S. Navy lighter-than-air.1 That spring, the first of several progressive cutbacks of LTA forces was announced. Ironically, fiscal 1957 represented the apogee of the postwar program: forty-four airships operational. From that September on, however, no further procurements were planned; indeed, the ZP (ASW) and ZW (AEW) squadrons were to be phased out as equipment wore out or was lost through attrition or was stricken. Rather than a swift vertical cut of the entire organization, the program would die by atrophy. It proved to be an inexorable, five-year agony, which eroded the number of bases and aircraft and which so depleted operations that, by early 1961, termination was inevitable.

On 1 June 1957, it was announced without explanation that the two Weeksville ASW squadrons would be decommissioned. This action would halve the number of units operational. Within four weeks, ZP-1 (ZSG-4 ships) and ZP-4 (six ZS2G airships) were eliminated. Net result: an organizational shambles. Though the Contiguous Barrier Squadron (ZW-1) would continue to operate, the ZPG-3W procurement was endangered as well—unless evaluation dictated otherwise.

The two Weeksville squadrons were hardly gone when, in September, the naval air facility itself was disestablished. Weeksville had provided facilities not only for LTA, but also for a helicopter squadron, a Navy motor pool, and other activities. The station’s location, moreover, was critical to lighter-than-air because it was centrally located among five airship bases strung along the East Coast between Massachusetts and Florida. The closing of NAS Weeksville reduced Lakehurst’s deployment options, a serious erosion of operational flexibility. With two squadrons eliminated, airship forces were reduced from a peak of forty-four to thirty-one aircraft.

A meeting of airship officers was called in early August 1957 to discuss the alarming prospects for the future. Capt. M. H. Eppes, now senior airship aviator on the CNO staff, presided. Program survival, it was agreed, was dependent on the airship’s performance with the fleet. A favorable operational evaluation might yet prove to the Navy that the airship was in fact a valuable adjunct to U.S. naval air power. But airships remained an alien thing: LTA had no spokesman of flag rank on the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations, or with the principal Atlantic Fleet commands. Its officers in the Bureau were, by 1957, very few—and they possessed little overall authority on airship matters. Lighter-than-air development, administration, and operation remained in the hands of the naval air organization, where it was a stepchild to the airplane. From the earliest years, the Navy had failed to recognize the airship as a special type, a vehicle requiring attention by officers qualified in and familiar with the platform and its peculiar problems. Other types—carriers, submarines, airplanes, even missiles—were normally accorded this special handling.

A ZS2G at Weeksville, NC. The ship has just landed, the last to do so at that station. On 1 June 1957 the Department announced—without explanation—that Weeksville’s two LTA squadrons, ZP-1 and ZP-4, would be decommissioned by month’s end. This action halved the number of ASW squadrons in the entire program, inciting an organizational shambles. Phaseout had begun. Lt. Cdr. J. M. Punderson, USN (Ret.)

Eppes and his colleagues arrived at a consensus. A “minimum program” was outlined that, if approved, would justify airships continuing as part of naval aviation. This program called for about sixteen operational aircraft and a total of twenty-five ships altogether. All ZSG-3s, it was agreed, would be stricken and the ZS2Gs mothballed. Eventually, all remaining ZSG-4s would be replaced with N-ships, thereby perhaps justifying an eventual replacement for the ZPG-2. A second AEW squadron, based at Moffett Field, was recommended. Additional ZPG-3Ws would be needed if this were adopted. An airship fleet this size would require that Lakehurst O&R remain active. Active R&D and training programs were deemed essential. The summary conclusion of this meeting represented a sober appraisal of the airship’s predicament in the latter 1950s:

If by some means acceptance of the employment of the ZP ASW Squadrons . . . can be achieved, and sufficient ZPG-3Ws can be provided to allow a substantial contribution in AEW, LTA will be perpetuated on its demonstrative merit.

Conversely if the present trend toward ASW strangulation and restricted (token) employment in AEW persists, the planned death of LTA by malnutrition will soon be realized.2

The next two years would witness a nibbling away at the remaining thirty-one aircraft and the few LTA stations so vital to the remnant program. ZX-11 at Key West was decommissioned that December and its three research ships (two ZPG-2s and a ZS2G-1) transferred to an HTA unit. They would languish there until spring 1959, when they were transferred to ZP-2.

Ironically, in the midst of this turmoil, the program again furnished an extraordinary demonstration of its potential. In June 1958, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) assigned a special project to the NADU, at NAS South Weymouth. An exploratory mission to the Arctic was ordered to be made that summer. A standard ZPG-2 in overhaul at Lakehurst was assigned and, after modification, departed Massachusetts on 27 July 1958 for Resolute Bay in the Canadian High Arctic, on the Northwest Passage. Basing out of Resolute Bay, on 9 August the ship, nicknamed Snow Goose, logged rendezvous with an International Geophysical Year (IGY) drifting station on T-3 (an ice island) less than eight hundred miles off the geographic pole, in the Arctic Ocean. There it dropped a packet of mail to the isolated scientists. The ship returned to South Weymouth on 12 August, having logged sixty-two hundred miles, including two landings and refuelings on Canadian runways without mooring. The expedition is unique in the history of naval aviation: the first and only U.S. Navy airship to cross the Arctic Circle.3

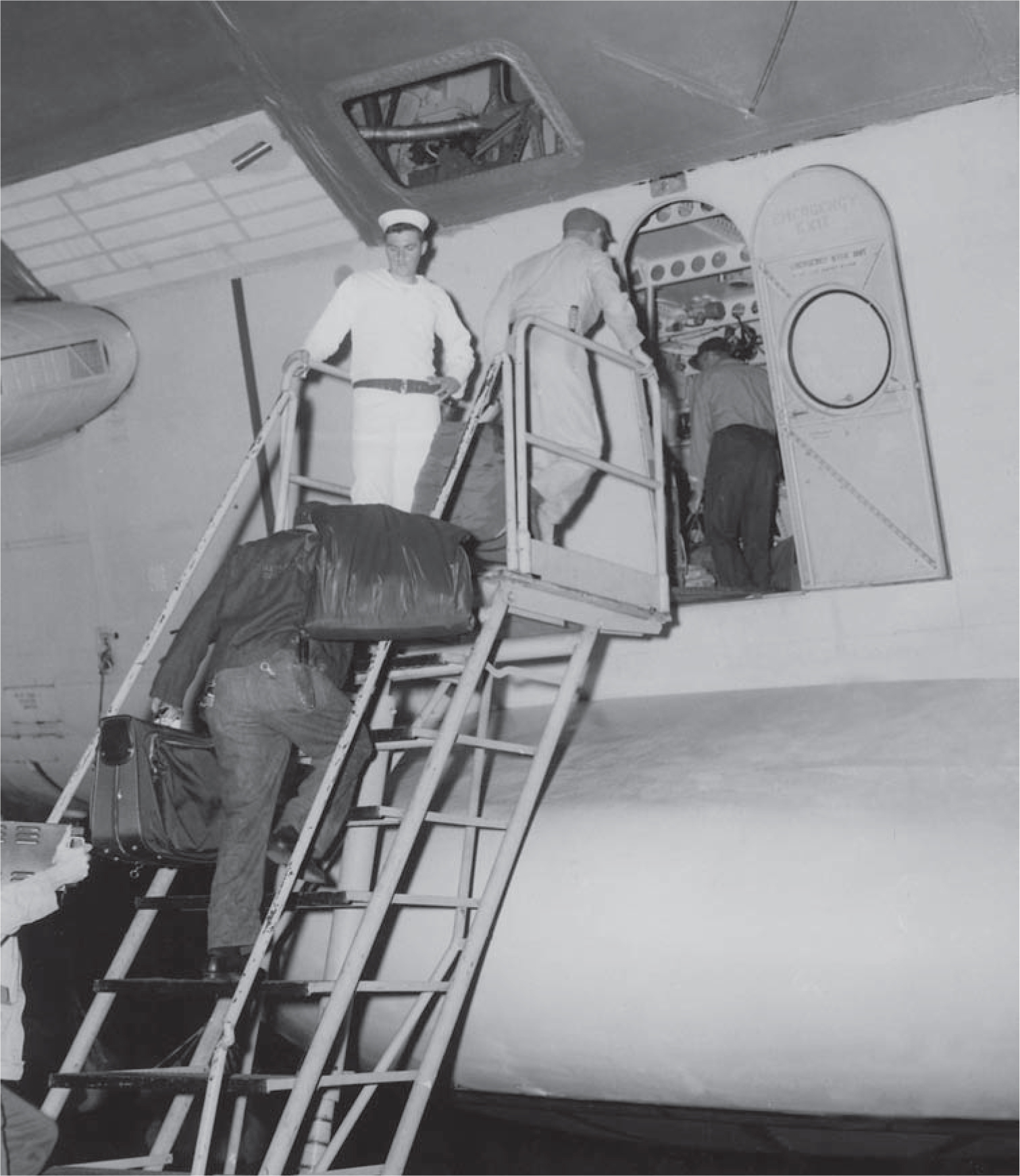

27 July 1958, NAS South Weymouth, MA. Gear comes aboard ZPG-2 BUNO 126719 for a project unique in naval aviation: “to conduct airship (blimp) flight operations in support of research in the area of the Arctic Ocean.” Assigned to the Naval Air Development Unit—an on-board support arm of ONR—the Polar Project was commanded by Capt. H. B. Van Gorder, USN. ATC F. L. Parker, USN (Ret.)

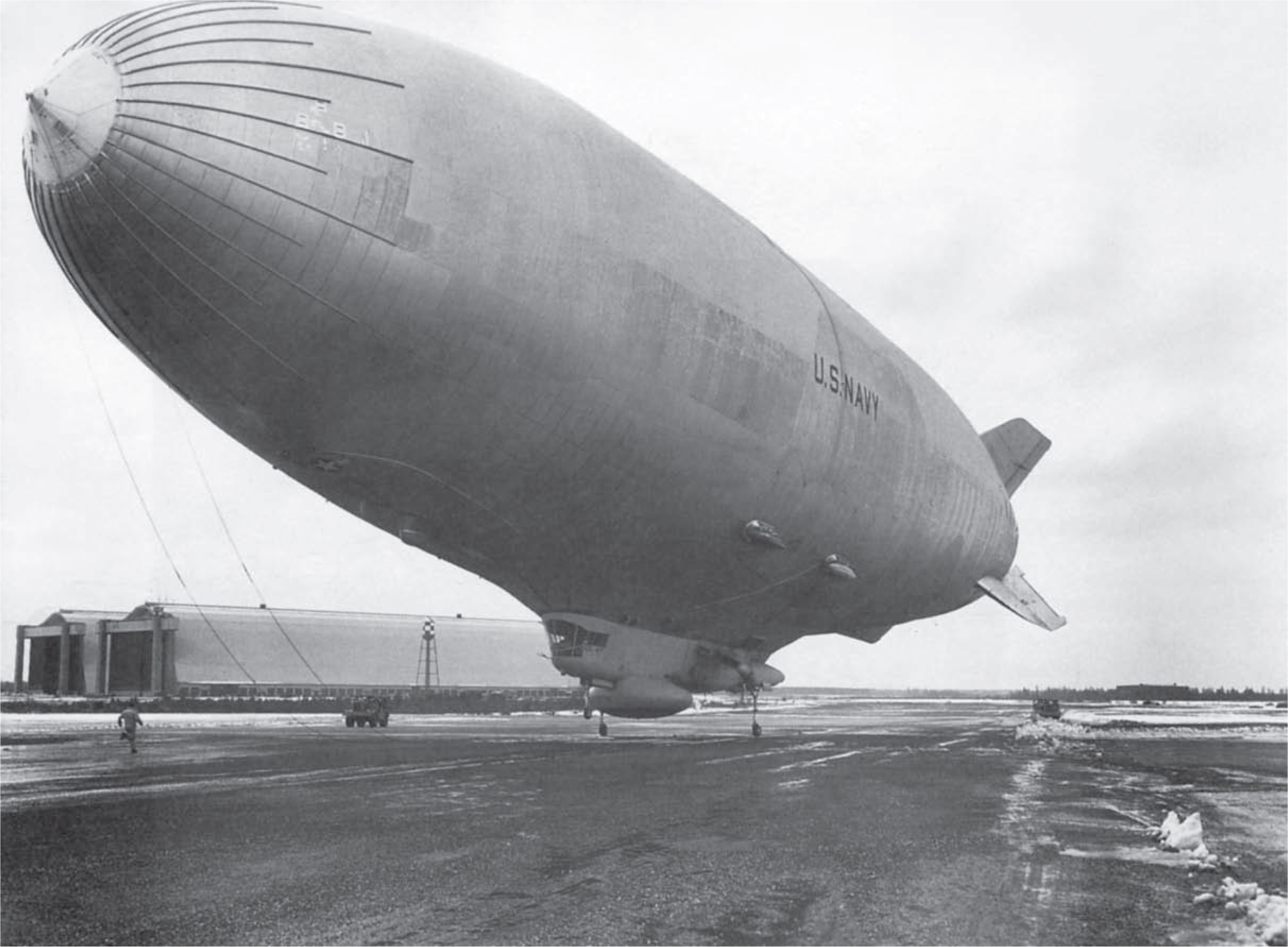

On the Northwest Passage: Resolute Bay (74° 43' N), 8 August 1958. Note the tundra terrain. “719” was the first Navy airship to cross the Arctic Circle. At 1102, 9 August, rendezvous was logged with Ice Station Bravo. Position: 79° N, 121° W—700 miles off the geographic pole. The sixteen-day operation demonstrated to some naval airmen that blimps could provide low-altitude reconnaissance from an advanced Arctic base over a wide radius. A follow-up mission was never ordered. M. Miller

Return from Arctic Canada, 12 August 1958. Here the fourteen-man aircrew gather for newsmen and photographers. With mission accomplished, all are pleased to be back. Note the size of the aircraft. ATC F. L. Parker, USN (Ret.)

The cutbacks continued. In December 1958, the reserve training unit operating a ZSG-3 from NAS Oakland was decommissioned. The last West Coast LTA unit was gone. Then, in the spring of 1959, the two airships of VX-1, the HTA development squadron that had inherited three blimps from ZX-11 in 1957, were transferred to Glynco. This effectively removed NAS Key West as a normal operationing base for LTA. Concurrently, aircraft allowances for the program’s last two ASW squadrons were reduced: ZP-2 from six to four ships; ZP-3 from five aircraft to four. That same spring, all ZS2G aircraft save one ship were ordered into war-reserve storage. (An aircraft so stored can be reassembled and flown again should the need arise.) There were only twenty-two operating airships remaining, including fourteen assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. In July, Glynco’s ZP-2 was again reduced, by half, to only two airships. For all practical purposes the squadron was gone. Two months later, in September 1959, the Navy Department announced that ZP-2 and the four-ship training unit based at Glynco would be decommissioned by 30 November. This action eliminated NAS Glynco from the program. Since the last reserve squadrons at Lakehurst also were eliminated that September, all lighter-than-air training had ended. South Weymouth’s experimental unit was reduced by one ship and ZW-1 reduced from a planned allowance of six to four aircraft. And in little more than a year, ZW-1 would be withdrawn entirely from the AEW mission.

A ZPG-2W idles on the mules for takeoff, 20 November 1958. Note the top man. Mission: to provide all-weather AEW services exploiting the largest radar antenna yet flown. In 1957 ZW-1 became part of the Contiguous Radar Barrier of the North American Defense Command (NORAD). U.S. Naval Institute photo archive

The LTA organization had been emasculated. Beginning in June 1957, the program had lost a total of ten squadrons: three Atlantic Fleet units, six reserve squadrons, and the experimental unit at Key West. Airship operating strength had been reduced from forty-four aircraft (the postwar peak) to only thirteen—with all activities save one NADU ship confined to NAS Lakehurst. The training of new pilots had been dropped altogether. In January 1960, the Navy’s entire LTA force consisted of a single ASW squadron and one AEW squadron of four airships each, plus one R&D ship at Lakehurst and another at South Weymouth. Termination appeared inevitable.

In mid-September 1959, CNO received a confidential memorandum that is one of the most significant documents of postwar lighter-than-air. On the occasion of his relief as commander, Fleet Airship Wing One, Capt. M. H. Eppes submitted a five-page summary of personal observations, comments, and recommendations on the status and use of lighter-than-air aircraft in the U.S. Navy.4 The captain enjoyed a unique perspective. He had been a qualified naval aviator (airship) since 1938, had later served with Naval Airship Training and Experimental Command, and had commanded the wing for a year. By 1959, the forty-seven-year-old captain was the most senior officer with recent fleet experience in lighter-than-air.

His report summarized the recent history of cutbacks, the effects these actions had had on the overall effectiveness of the Navy’s airship forces, and the resulting impact on morale. A review of the airship’s contribution to the development of antisubmarine equipment was also offered. Attention was drawn to the low esteem granted LTA within the Navy Department, the lack of general support for the program, and the implications of these attitudes and cutbacks for the future of the naval airship. The document concluded with recommendations for the future, including the convening of a board that would “completely and objectively” examine the value and future of LTA in the United States Navy.

When the report was routed up the chain of command, it incurred some rather cynical reactions among the Atlantic Fleet commands. The commander, Fleet Air Wings, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, noted that “as a result of directives issued in recent years it appears that the LTA program has reached a point of diminishing returns.”5 The commander, Naval Air Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, stated,

ZPG-2 BUNO 135448, Lakehurst, 14 May 1959. The ship had collided with Hangar No. 3 on radar approach in heavy fog. One crewman was killed and the aircraft stricken. AMCS Daniel Brady

The need is obvious for the Navy to review critically all programs to determine in each individual case whether the benefits realized are commensurate with the cost in terms of personnel, money, and facilities. Viewed in this perspective, the LTA program is of questionable value. . . . No special board is necessary to arrive at this decision. . . . [I]t is recommended that action be initiated to terminate the entire LTA program at an early date.6

The commander, Antisubmarine Defense Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, seemed more favorably disposed toward the airship, noting that a well-supported program could make a “substantial wartime contribution” in ASW surveillance and convoy escort. Nonetheless, in light of the recent “limited progress” made by LTA in ASW and the diminishing efforts to support the program, the recommendation was made that lighter-than-air be terminated.7

Eppes had opened the door officially on the matter, and the fleet had reacted firmly and coldly. On 11 January 1960, when the commander in chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, forwarded his own recommendations to the CNO, he was not at all disposed to defend the program or inclined to reexamine its particular problems:

The contribution of the LTA program to Fleet readiness has progressively been reduced to an ineffective level.

Accordingly, CINCLANTFLT concurs with the Commander, Naval Air Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, and Commander, Antisubmarine Defense Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, that the LTA program should be terminated.8

In March 1960, Captain Eppes, now commanding officer of the Lakehurst station, received an official reply from the deputy chief of naval operations (air). His recommendations were ignored. There would be no study, reconsideration, or explanation. The reply merely stated, “It is anticipated that the airship program will be continued on a modest scale in order to preserve the state-of-the-art and to provide means for continuation of research and development in the field.”9

Snow-laden ZPG-2W, December 1958. Note the helium trailer. Modern airships offered unequalled on-station endurance, though snow and icing could hinder operations. Projects to assess all-weather capability were the focus of investigation during 1955–57—results applicable to maintenance of a continuous AEW radar-barrier against enemy targets approaching the continent. USN courtesy Cdr. C. A. Mills, USN (Ret.)

In danger of load collapse, a ZPG-3W is emergency docked in severe cross-winds. Various snow-removal schemes had been tried for moored out airships, to scant result. AMCS Daniel Brady

Other negative signals were evident at Lakehurst. A reduction-in-force (RIF) directive had been issued for the station’s civilian work force in fall 1959, the latest in a series of annual cuts that had reduced O&R personnel by 45 percent since 1954. New Jersey congressmen, responding to pressures from increasingly anxious constituents, dutifully queried the Navy Department regarding these reductions. In reply, these cuts were defended as altogether “necessary and proper.”

The business community in the Lakehurst area also was uneasy. The station payroll for military and civilian personnel was about $17 million that June. The air station had become the economic backbone of industrial employment in Ocean County and, by 1960, its largest industry, employing about 50 percent of the area’s industrial workers. Most of these were skilled, highly paid employees. Anxieties were in no way eased by a Department of Defense report released in June 1960, reporting that airplanes and helicopters were proving more effective than blimps in ASW. The airship’s comparatively slow speed was deplored. Airplanes, moreover, were more maneuverable and thus less susceptible to hostile fire. It also was pointed out that airplanes were less subject to high winds, presumably a reference to Lakehurst’s procedure of limiting docking and undocking to wind velocities of less than twelve to fifteen knots. The virtues of helicopters over airships also were noted.

Lakehurst from the flight deck of a ZPG-2W. Force reductions by the CNO and successive elimination of bases had by 1959 confined all Navy LTA to Lakehurst. The program continued by virtue of ad hoc measures and much improvisation. In 1961, all fleet airship commands would be disestablished. When the ICBM became the prime threat, all AEW aircraft became obsolete. USN

Two weeks later, tragedy compounded this unhappy atmosphere. At 0730, 6 July, a ZPG-3W departed Lakehurst to a training area off New Jersey. The ship had been operational for less than six months, having been accepted from Lakehurst’s Airship Test and Development unit in late January. Aboard were eight officers and thirteen enlisted crewmen. At approximately 1429, about sixteen miles from Barnegat Inlet, a loud sound was heard by members of the crew after which the ship slowed and settled slightly. Corrective action was taken, but seconds later the ship’s attitude changed to forty-five degrees nose down, and she settled rapidly. The aircraft plunged into the sea in a steep nose-down attitude. No emergency messages were received. The flight crew attempted to escape the sinking car, hampered by the envelope collapsing around them. Four men were rescued by fishing vessels in the immediate vicinity, but one died later. It was the worst nonrigid airship accident in the forty-five-year history of the program.

Admiral Rosendahl boards K-43, 19 March 1959, his anger undiminished against “anti-airship elements” in the Navy Department. An era of aeronautics was ending: the last King-ship in service was about to log its final sortie. Capt. J. R. Van Evera, station CO, at right; center, Capt. M. H. “Henry” Eppes, CO, Fleet Airship Wing One. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

Capt. M. H. Eppes; Adm. Paul D. Stroop, chief, Bureau of Naval Weapons; and Cdr. Walter D. Ashe, director of research, Airship Test and Development, on Mat 1, 29 January 1960. Note the nylon flight suits. Admiral Stroop was first chief, BUWEPS—formed in 1959 to replace the Bureaus of Aeronautics and Ordnance. BUWEPS would preside over the dismantling of the LTA program (1961–64). USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

The squadron’s three ZPG-3Ws were promptly grounded. Salvage operations were begun immediately, and the last of the wreckage reached Lakehurst on 22 July. A board of investigation concluded that “the primary cause of the accident was due to the failure of the helium envelope. The specific reason for the envelope failure . . . has not been established.” The possible causes were only two, however: a defective envelope seam or inadvertent low envelope pressure.

A number of directives were issued as a result of the tragedy. The airships’ two-ply cotton bags were replaced with Dacron envelopes. Changes to the helium low-pressure warning bells were made. The general alarm button was relocated, and the low-pressure warning included on the pilot’s check-off list. The squadron’s quality-control program was thoroughly reviewed.10 The government’s investigation and civil litigation would persist beyond 1961.

Delivery of ZPG-3W BUNO 146297, 5 April 1960. It was the last airship accepted by the United States Navy. On the mat, from left, Capt. Fred N. Klein Jr., CO, Fleet Airship Wing One; Karl Arnstein and Rear Adm. Karl Lange, USNR, both with Goodyear; T. A. Knowles, president of Goodyear Aerospace Corporation; and Captain Eppes, in command of the air station. The only service in the world to operate airships was the United States Navy, whose sole supplier was Goodyear. The relationship was very close. Note the “kneeling” nose wheel and ship’s ladder. USN courtesy Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

Navy Department assumptions notwithstanding, the airship’s potential in antisubmarine warfare had not escaped the interest of the White House in this period. A study by the president’s Science Advisory Committee had suggested that a trial be performed at sea, maintaining an ASW airship equipped with passive sonobuoys continuously airborne in the vicinity of the Navy’s new and highly classified Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), consisting of an array of hydrophones moored to the ocean floor to monitor the noises emitted by surface ships and patrolling submarines.11 The commander in chief, Atlantic Fleet, was asked to conduct an evaluation of the airship as an airborne backup for SOSUS.12 Operation Whole Gale, as it was named, would be the last major fleet operation in which the airship participated. Thus, in the summer of 1959, ZP-3 was ordered to prepare to maintain at least one ship “on station” offshore continuously, twenty-four hours a day for two months. The aircraft were to react to target information and maintain sonar contact with any submarines penetrating the patrol area. Intensive readiness and training operations were conducted between September and January 1960 during which tactics were developed and combat aircrews trained for the all-out effort to follow. Six ZPG-2 aircraft and five combat aircrews were assigned.

Squadron ZP-3 touches down after 72.9 hours in the air, 16 March 1960. This ship was one of six assigned to the last major fleet exercise involving airships, Operation Whole Gale, an evaluation of LTA as airborne backup for SOSUS. Note the mules on each side of the touch-down point and sprinting line runner—one of two on the bow lines. USN courtesy Capt. F. N. Klein Jr. USN (Ret.)

The operation began on 1 February 1960. Sustained on-station flights exceeding forty hours were logged through the most severe winter weather ever recorded off the East Coast. It was, quite literally, an all-out effort. One ship remained on station nearly ninety-five hours—a record for the program. By the end of March, ZP-3 had logged more flight time than in any two months in the history of LTA—1,644 hours. In-flight refueling in heavy winds and blowing snow became standard. Squadron ships (and HTA units) were on station for 1,277 hours during the two-month exercise, an unprecedented 88.6 percent coverage factor.

Operation Whole Gale concluded. ZPG-2 “562” and its combat aircrew had hung to seaward, on station, nearly ninety-five hours—a record for the program. LTA had performed admirably. Notwithstanding a “Well Done” from commander, Submarine Defense Force, Atlantic Fleet, momentum toward final phaseout did not ease. USN courtesy NAA/R. G. Van Treuren

This demonstration notwithstanding, the airship’s political vitality did not improve. The report of this unusual exercise, slated to reach the White House that summer, did not reach the president’s advisory committee until after March 1961—too late to influence the Navy’s final decision against the program, or so it seemed.

Spring 1961 proved to be a turbulent and anxious time. That March, reports reached New Jersey’s congressmen that the elimination of lighter-than-air was under review. The media were informed—and the news went public with a vengeance. The developing drama was made to order, granting the state’s mass media a prolonged news and editorial field day. Statements, charges, and reactions were offered while the fate of the LTA program was debated behind closed doors in Washington. In hope of influencing the final decision, briefings were prepared, meetings held, inquiries made, pressures applied. Alternative uses for the Lakehurst air station’s industrial plant and its operational facilities were put forth and discussed. Much public discussion ensued as to the value of NAS Lakehurst and lighter-than-air to the Navy’s overall mission—and to the New Jersey economy. The “Lakehurst Crisis” of 1961 received prominent public scrutiny well into July. And at Lakehurst plans were dutifully prepared for deflation and storage of the last airships. In the end, the Navy Department would have its way; but, in the early months of 1961 it seemed possible that program termination might somehow be averted.

ZPG-3W BUNO 144243 is “ripped” at NAS South Weymouth to minimize damage to the aircraft from uncontrolled motion, February 1960. A sudden gust had overturned one of the ground-handling mules, and a line parted, allowing the ship to meet the hangar. Cdr. C. A. Mills, USN (Ret.)

By early March, reports had reached New Jersey senator Clifford P. Case that the Navy Department had a disestablishment proposal in hand. A letter of inquiry was promptly sent to Secretary of the Navy John B. Connally Jr. Inasmuch as all Navy blimps were concentrated at NAS Lakehurst, these reports were understandably a matter of “deep concern” to the senator. The timing of these reports, moreover, was particularly disturbing in light of the nation’s serious economic slump and the nearly 9 percent unemployment affecting New Jersey. Case hoped to avoid any precipitous decision that might impact economic revival back home. “It should be noted, too, that this honored old airship program finds a warm and affectionate place in the hearts of the people of my state, through its long association with Lakehurst.”13 The good senator’s letter was released to the press on 3 March and was immediately carried in all area media. New Jersey senator Harrison Williams and Representative James C. Auchincloss (R-N.J.) also initiated action within Congress and the Navy Department at this time.

One week after Case’s inquiry, the Navy replied. The senator’s apprehensions were confirmed; his information was “substantially correct.” The SecNav’s tone was direct, and ominous indeed:

The Navy budget for FY 1962 as submitted to the Congress does not include enough funds to permit the continued operation of all naval aviation forces now operating. As you may recall, correspondence to members of Congress has stipulated that the continuation of the LTA program was contingent upon the Navy’s budget allocations. Reductions in the LTA program and consideration of its final termination has come about because the functions airships perform cannot compete with the tactical importance of other naval programs for the defense dollar.14

Reaction was sharp and immediate. Case and Representative Auchincloss, in a joint statement, noted that the Navy’s report “painted a most unfortunate picture.” Ocean County officials reacted by appealing to the Navy to convert the naval air station into a missile base rather than abandon the facility. Serious economic damage to Lakehurst and surrounding communities was forecast. The station’s commanding officer considered closing unlikely, because, in addition to LTA, Lakehurst hosted two helicopter squadrons, the Aerographer’s Mate School, the Naval Air Test Facility, and a Naval Air Reserve training program.

Senator Case seemed well informed. When contacted by the New Jersey Courier for comment, his aide confirmed the existence of “a strong report in the Pentagon to eliminate the lighter-than-air program at Lakehurst. It’s more than a mere rumor.”15 Overall, Lakehurst officials remained reassuring. Lighter-than-air was but one element of station mission; elimination of airships might actually increase other on-board activities.

Civilian employees lobbied especially hard. Their organization, the NAS Lakehurst Development Association, mounted a determined campaign designed to influence crucial politicians and the Navy Department. Their objective was to distance Lakehurst O&R from the LTA program. This argument held merit. In 1955, the air station had been designated a class “A” facility. That is, it was able to satisfy the requirements for overhaul and repair of all types of naval aircraft. Thus, by 1960, an impressive variety of aircraft and aircraft models had been modified at Lakehurst: airships, helicopters, and airplanes. Less than a quarter of the total had been blimps. But it was to no avail. Pleas, facts, arguments, and warnings notwithstanding, the decision would go against them. In late June 1961, the Navy’s official announcement included Lakehurst O&R in its termination plan.

The clamor persisted. Ocean County officials delivered a memorandum to Gov. Robert B. Meyner that warned of serious economic consequences if the LTA program were terminated. Continued operations and use of Lakehurst’s O&R were recommended for another fiscal year while a congressional investigation assessed whether airships retained a viable military role. And if not, alternate uses of the base were to be explored.

In late May, Admiral Rosendahl came forward. In a twenty-two-page statement before the House Appropriations Defense Subcommittee, he vented his long-simmering frustration with the Navy Department, decrying “the general careless and indifferent attitude in the Department in anything having to do with LTA.” The pending proposal to terminate at the end of fiscal 1961 was, in his estimate, “indefensible from any standpoint.”16

All but the most hopeful were now resigned to the inevitable. Navy lighter-than-air was ending. The only uncertainty was whether one or two R&D N-ships might escape the termination order. Under the headline GLUM LAKEHURST AWAITING END OF BLIMPS AND HUNDREDS OF JOBS, the New York Times had concluded that the Navy had indeed decided to deflate its famous “gas bags.”17 Interviews with area residents, businessmen, civilian employees, and naval personnel emphasized the impact of the pending termination. One area farmer, for example, seemed to summarize the prevailing sentiments of the air station’s many neighbors: “These blimps, we’re sure going to miss them after having them around all these years. And the Navy folks have been mighty fine neighbors.” Businessmen and customers feared financial losses. Civilian specialists dreaded loss of their jobs and the leaving of homes, neighbors, and friends.18 The air station prepared to celebrate its fortieth anniversary that June. The usual enthusiasm was missing.

Two “Willy Victors” complete their service changes at Lakehurst O&R, 15 June 1961. The WV-2s were O&R’s last major assignment before the CNO’s announcement to decommission all fleet airship commands and, as well, inactivate O&R. The naval air station—an economic anchor—was alive with rumor. Termination orders reached the base teleprinter at 1811, 26 June 1961. USN courtesy ADC J. A. Iannaccone, USN (Ret.)

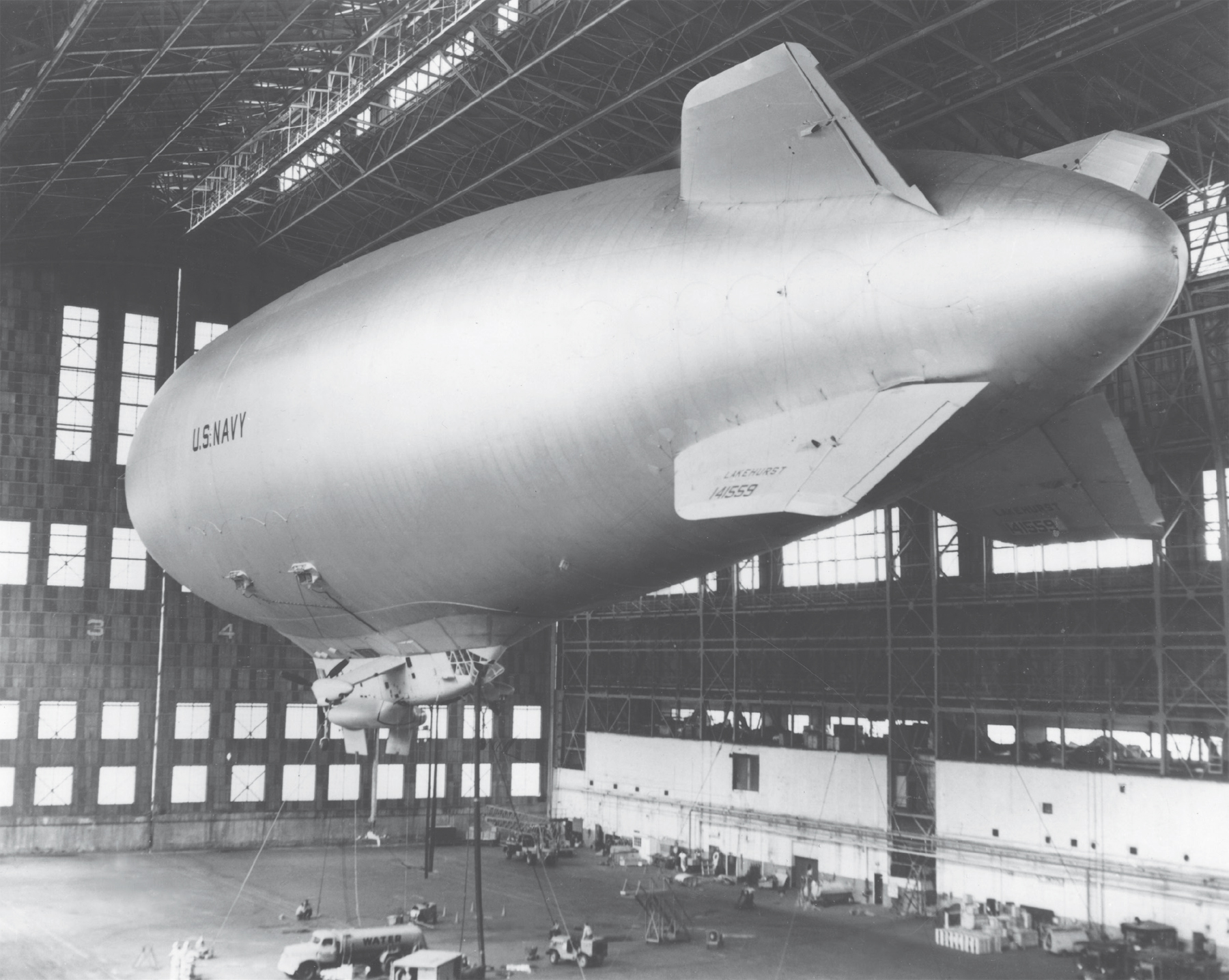

The termination order reached the naval air station’s teleprinter at 1811 hours, 26 June 1961. It read in part: “COMBINED FIRST AND SECOND QUARTER FY 62 AIRSHIP SCHEDULES CANCELLED. DEFLATION, PRESERVATION AND STORAGE OF AIRSHIPS EXCEPT ZPG-2, BUNO 141559 AND 141561, TO COMMENCE IMMEDIATELY AND BE COMPLETED BY THREE NOVEMBER 1961.” And no time was to be wasted: “BUREAU DESIRES REDUCTION-IN-FORCE OF APPROX 45 PERCENT BELOW PRESENT CIVILIAN STRENGTH OF O&R DEPT BY 30 SEPT AND REMAINDER BY 30 NOV 1961.”19 Phasing out of the department’s workload would begin immediately. No further customer service was to be accepted by O&R unless such did not interfere with the deflation and inactivation schedule defined by Washington. The two LTA squadrons, ZP-1 and ZP-3, along with Fleet Airship Wing One, were to be decommissioned on 31 October 1961. Eight of the remaining ten operational aircraft would be deflated, carefully preserved, and placed into warreserve storage. Lakehurst O&R was made responsible for the preservation work before that department was inactivated. Affected civilian employees could find other employment using a special outplacement program already planned.

The banners of the New Jersey press shrieked the news: NAVY ABANDONS BLIMPS. The air station’s own newspaper in its lead article headlined the decision: FLEET LTA, O&R TO BE CLOSED OUT BY END OF NOVEMBER.20 And in one of his last public statements as an officer on active duty, Eppes noted with sadness, “The real tragedy was that a proven type of transport has been unreasonably condemned by one famous accident.” Nevertheless, “it’s an order from Washington. And we’ll follow it like any other order.”21 On the thirtieth, Eppes retired to civilian life in a brief ceremony on the mat. Conspicuous by their absence were the silver blimps. Symbolic of the advancing technology that had overwhelmed the program, a Navy jet roared overhead as a thousand civilian and naval onlookers watched the change of command that made Capt. Frederick N. Klein Jr. NAS Lakehurst’s twenty-fifth commanding officer.

The new CO’s immediate concerns were considerable. The inactivation of O&R was to commence immediately and be completed in five months. This activity alone would involve a myriad of details. Concurrently, the wing and the last two squadrons were to be decommissioned by the end of October. All station personnel not directly associated with the phaseout and inactivation were to be separated as soon as possible. The ZPG-2s, 2Ws, and 3Ws still flying, with the exception of two Nan ships (for R&D), had to be deflated, preserved, then placed into war-reserve storage—all by 3 November. O&R buildings not needed for support of other station operations would be inactivated. It was planned to close the old fabric shop, Hangar No. 2, and, after one year, Hangar No. 1. Spaces in Hangar No. 5 would be reassigned. The new Aircraft Maintenance Department (AMD)—a direct successor to O&R—would expand and share hangar spaces with the Naval Air Test Facility on board.

Parts to support the two R&D ships would prove to be an especially knotty problem. Spares were set aside from stock and from the airships already in storage. Nonetheless, it was noted ominously that if other parts were in fact needed later, a decision would be made at that time “whether to procure or cannibalize from deflated war reserve airships.”22 Indeed, equipment from the defunct program promptly attracted attention. Within weeks, representatives from other activities were visiting Lakehurst to discuss requisitioning of equipment.

The termination announcement had excluded two ZPG-2s. Two R&D projects were responsible for this reprieve. One was for the Navy. Code-named Clinker, this was an ASW infrared project initiated in 1958. The other was the “flying wind tunnel” airborne aerodynamic study under way in cooperation with Princeton University. Exploratory investigations beginning in 1960 had led to the Navy-Princeton venture. Its principal proponent, David C. Hazen, professor of aeronautical engineering, had recognized the airship’s virtues as an airborne laboratory during a chance ride in the spring of 1960. Discussions with Lakehurst led quickly to the conviction that the airship held considerable potential as a flying wind tunnel uniquely suited to produce the conditions required for the investigation of the low-speed regime of STOL (short takeoff and landing) and VTOL (vertical takeoff and landing) aircraft.

A test program had been initiated using a jerryrigged ZS2G-1. As the summer progressed, the unique capability of the airship platform became increasingly obvious. “For the first time a technique was available whereby it was possible to test models of essentially unlimited size without the presence of any disruptive wall effects.”23 As one result, presentations were made in fall 1960 urging that a larger ship be converted for use exclusively as a flying wind tunnel. A demonstration flight was made on 12 January 1961. Soon after, however, it was learned that termination of LTA was under review, so steps were taken to brief those responsible for the impending decision. The desirability of retaining two ZPG-2 aircraft was emphasized; no change in either budget or personnel would accompany these in-flight investigations, it was argued. By this time, Hazen had become familiar with the airship’s political problems: “I have learned that the entire airship program seems fraught with emotion. The very mention of the machines causes old LTAers to become nostalgic, and heavier-than-air people to see red.”24 Hazen summarized his case: the two airships he wanted represented an excellent and inexpensive way of amending the “appalling lack” of experimental test data in the field of low-speed aerodynamics.

“Flying wind tunnel,” BUNO 141559, 23 May 1961. The cooperative project with Princeton University begun in 1960. The test model is mounted, inverted, on a thirty-three foot retractable strut through the control car. The ability to conduct tests free of wind-tunnel effects was realizing unique data sets. Pleas for continuation unavailing, orders would end all R&D flying in 1962. Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

These arguments proved persuasive. On 26 February 1961, the Navy and Princeton University jointly announced a decision to operate two airships. And four months later, in June, two R&D Nan ships were specifically excluded from the decommissioning plan.

Lakehurst lost little time in complying with the decommissioning orders. All deflation work took place in Hangar No. 1, its deck the scene for so many triumphs and disappointments. During July–August, eight airships in storage “cans” were removed, stricken from inventory, and their components salvaged for use elsewhere in the Navy Department or Defense Department establishment.

The deflation and storage process was, as always, a painstaking effort. The list of steps for the deflation of a Navy airship, and preservation procedures for the envelope, control car, and their hundreds of components, ran to six legal-sized pages. Many of the parts were common to any military aircraft. But preparation of the car required its detachment from the envelope. Considering that a ZPG-2 contained 1 million cubic feet of helium and consisted of more than seven thousand square yards of fabric, the complexity of the process should be appreciated.

Envelopes were taken to the fabric shop storage wings; there, under controlled humidity and temperature, the rolled bags would retain a long shelf life. The control cars in their turn were systematically stripped of nearly all accessories, then (with their principal components) carefully preserved before being cocooned in airtight and vapor-proof material. The entire process was conducted step by step on a strict working schedule. Approximately one thousand man hours and about five working days were required per ship. The techniques, care, and workmanship employed by the skilled O&R staff had been perfected over forty years of Lakehurst experience.

The unhappy work advanced ahead of schedule. Two airships were deflated that July, with deflation and storage slated to commence in August on two more. By 1 September 1961, storage was complete on three airships—and all but two had been deflated. The last deflation was in progress by mid-September. Fifteen bags were now in storage, including eight Nan ships and two new Dacron envelopes for the ZPG-3W. But fourteen ZSG-4 and ZS2G-1 envelopes had been removed and stricken, as per directive. Neither model would be resurrected. Two spare bags were cut up for cocooning the control cars. By early October, all eight airships scheduled for storage had been deflated. And storage of the envelopes was essentially complete. As this was completed and related work phased out, emphasis shifted to the closing of shops, cleanup of O&R areas, and the return of material to the air station’s Supply Department.

Except for preservation of a few components, by early November the entire preservation program stood complete. Six cars and their components were now sealed in containers along the east end of Hangar No. 1. Another five were in storage cans adjacent to Hangar No. 4. Beyond Lakehurst, little LTA-related equipment remained. Four mooring masts were left in operable condition: one each at NAS Bermuda, NAS Glynco, NAS South Weymouth, and at Lakehurst. Total cost for the inactivation effort was nearly $1,200,000.

Gratifying progress had been made with the employee out-placement program. Teams from the O&R departments at Quonset Point, Norfolk, and Cherry Point visited that July to interview prospective employees. Job offers from these and from other government activities resulted in the relocation of nearly fifty employees. In August, recruiting teams from NAS Pensacola, NAS Jacksonville, and a number of private firms also interviewed and made their selections. By November, 210 Lakehurst employees had been removed from the rolls through transfers, reassignment, resignations, and separations.

The melee over termination continued through 1961. Indeed, the escalating Berlin crisis, begun when Soviet troops sealed off East Berlin on 13 August, had heightened the public debate. President John F. Kennedy suddenly requested $3.5 billion to demonstrate America’s defensive readiness on behalf of the former German capital. This would bring nearly a billion dollars in fresh funds to the Navy. Senator Williams, who earlier had expressed “shock and disappointment” at the June announcement, wrote an angry letter to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara requesting that “an imaginative effort” be made to access fully the potential of Lakehurst’s facilities. Senator Case, for his part, sponsored a bill requiring the secretary of commerce to study the economic impact of deactivating military installations in areas of substantial unemployment. Hearings were held that fall. The Ocean County Board of Chosen Freeholders requested a reexamination of the Navy’s decision in light of stepped-up national defense. Governor Meyner suggested that the Lakehurst station be used as a commercial jetport. It seems that every possible argument was introduced. Admiral Rosendahl issued a statement that a Navy blimp could easily have saved the sinking space capsule of astronaut Virgil Grissom. It was lost to the Atlantic because the rescue helicopter could not lift it. Whatever their individual or collective merits, these proposals had no lasting effect. The Navy Department remained steadfast.

But steps were taken to enhance the station’s continuing military vitality. Existing activities were expanded to replace lighter-than-air. The Naval Air Test Facility was the principal beneficiary in this regard, receiving additional support to conduct high-priority projects for naval forces afloat as well as for the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA). Late in 1961, antisubmarine squadron VS-751 became a fully operational tenant command. The base, moreover, continued to host the only aerology and parachute rigger schools in the naval service. And Lakehurst’s two helicopter utility squadrons were still operating with the fleet. The air station’s commanding officer was publicly optimistic as to the future of his command: “The U.S. Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, is a permanent and important segment of the Navy and this community. It is expanding and I foresee nothing to change this ever-increasing role in our nation’s security.”25

In late September 1961, a meeting was held on base to discuss the future of the flying wind tunnel project. Considerable lobbying was under way to extend the one-year test program, which was yielding excellent results. From three to five years of flying, perhaps longer, remained. Hazen was pleased with his results: “The test results run to date have already demonstrated the heretofore unsuspected magnitude of the wind-tunnel wall effects as the transitional portions of a typical VTOL/STOL flight profile are simulated.” Test flights of five to eight hours had become routine, nearly all over water where offshore conditions were smoother. Despite organizational deficiencies, which were curtailing flight operations, ZPG-2 141559 was a workable flying wind tunnel laboratory.26 But Hazen and his team were unable to convince BUWEPS that the flight program was an asset realizing genuine scientific returns. The scientists had no choice but to assume that their test aircraft would have to be ready for deflation by June 1962. (A two-month extension, through August, was granted in late May.) A compressed test schedule was therefore established for the balance of the fiscal year.

In the ensuing months of 1961–62 the Navy flight crews, civilian support, and university engineers redoubled their efforts and flew as often as possible. Ironically, in view of the Navy Department’s intransigence, the last test, in late August 1962, demonstrated conclusively both the capability of the airship as a test platform and the significance of tunnel-wall interference effects. Hazen was deeply disappointed by the decision to proceed with deflation: “We had just scratched the surface of the problem and could have used several more years.”27

The calendar moved toward conclusion. On 12 May 1962, the two blimps still operational put in a final public appearance during Lakehurst’s Armed Forces Day open house celebration. More than fifty thousand visitors (the author among them) watched as the last two overflew the mat and demonstrated touch-and-go landings. For many, this was their first, and last, opportunity to see the huge aircraft. Two weeks later, the date for the last flight of a U.S. Navy airship was announced—31 August 1962.

Washington had ordered no closing ceremony as such. But this was quietly circumvented and a special “last flight” crew selected. An unofficial memorandum was sent out in July to “All LTA Old-Timers,” inviting them to participate in the last Navy airship takeoff, landing, and docking—and to pass the word. The media were also invited to cover the event, but no media were authorized to fly.

“559” ballasted for zero-airspeed tests, NAS Lakehurst, 14 September 1961. The process for war-reserve storage near complete, two N ships received reprieves into fiscal 1962: one as a flying wind tunnel and BUNO 141561 for Clinker—a classified ASW project, the sea trials for which had begun in 1958. Despite the potential for excellent results, orders had test flying ending by 31 August 1962, the date set for termination of all LTA operations. Capt. M. H. Eppes, USN (Ret.)

The last day of August 1962 dawned clear and warm. The final operational flight had ended early that morning after an all-night test flight. Inside Hangar No. 1 Crew Chief Daniel “Dan” Brady and his men prepared “559” for its final sortie. Sometime before noon, the airship was undocked one last time and pulled onto the mat. Here the ship vaned to the mast as Navy men and their families, representatives from the media, and a few VIP guests assembled early that afternoon. Shipmates met and reminisced—a poignant occasion for most hands. In the words of one participant, the atmosphere that day was somewhere “between a reunion and a wake.” At approximately 1330, as cameras clicked and the small group looked on, Admiral Rosendahl, with Capt. Frederick Klein Jr. and Capt. R. F. Stultz, USN, Klein’s successor as station CO, climbed the ladder beneath and took their stations. The “559” flight crew, already on board, readied for departure. In the pilot’s seat this afternoon: Cdr. Robert “Bob” Shannon, USN. All ready, at approximately 1400 hours the airship was unmasted, after which Shannon opened his throttles, and the aircraft began its takeoff run. After a short roll, “559” lifted clear.

ZPG-2 141559 headed slowly southeast toward Toms River. On board, the mood was somewhat subdued, but the flight crew and “honorary copilots” chatted and remembered, each man marking the moment in his own private way. As the blimp droned on at about five hundred feet, everyone took a turn at the flight controls. En route to Toms River, one homeowner was seen to dip the colors in salute to the passing airship. “We were all quite moved by this episode,” Shannon later recalled. It was a private tribute to the aircraft, and to the program.

The ship passed over Toms River to Flag Point, the home of Admiral Rosendahl; there it circled. Then “559” steered north, to the area of Lakewood before the return leg to Lakehurst. After an hour or so aloft, and for the benefit of those assembled for the final landing, the airship was turned southwest. Minutes later, the silver ship appeared over the naval air station against a flawless sky, on approach. The final touchdown in front of the big hangar was logged at about 1536. NAS Lakehurst had brought home its last airship. “559” was picked up by the mechanical mules, stopped, and steadied. The assembled LTA “old-timers” were now invited to help man the mooring lines for picture taking. This concluded the semi-official formalities. Only “debriefing” over drinks remained to mark the occasion. “There was no ceremony, no speeches, no fanfare of any kind to mark the occasion. A hundred or so people gathered to take pictures but that was all.”28

After masting, the ship was left on the field until early evening, when conditions were more favorable for docking. When airship “559” crossed the hangar sill that Lakehurst evening, an era of naval aviation begun forty-seven years earlier ended. The air station’s operations schedule for 31 August 1962 noted simply,

This flight terminates the operation of nonrigid airships at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey.29

Five days after the final flight, on 5 September, work orders were cut for the deflation and long-term storage of the last two operational airships in U.S. Navy inventory. Finally, the watch for “561” was closed out.

Now only 141559 remained—the last operational airship in the United States Navy, the last military airship anywhere. The “pressure watch” continued faithfully: the time, signature of the man on duty, and ship’s condition were recorded every four hours. But on 24 September 1962, the pressure watch was secured for the last time.

Preparations for deflation of “559” began immediately. All loose gear was removed, tagged, and prepared for long-term storage. Next, confidential equipment was removed, packaged, and preserved. The engines were checked, the fuel system purged, and the two engines preserved separately, as were the propellers. Large wooden boxes were used to stow the envelope kit and allied parts.

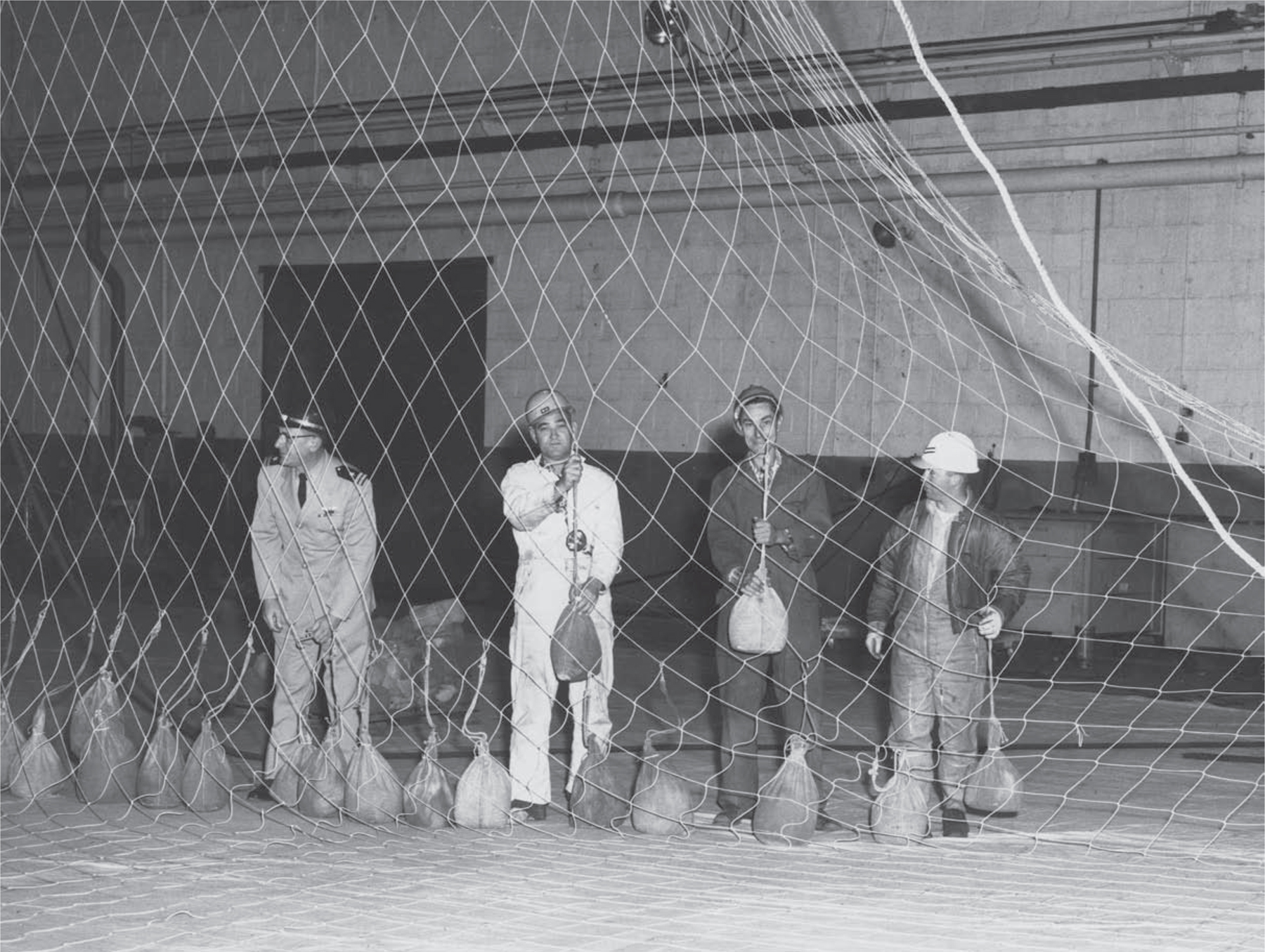

All landing lines, external lights and wiring, instruments, and the major controls were readied for detachment from the envelope. The control car fairing and rip cord were disconnected, and the fins also prepared for detachment. Nose cone and battens were removed. When all was ready, the huge aircraft was floated up several feet and a car cradle rolled into position beneath. The ship was then ballasted down onto its cradle and secured. Once detached from the control car, the still-inflated envelope had to be restrained, so an inflation net had been draped over and ballasted down with canvas bags filled with shot. Various envelope accessories were removed—most of which were packaged and preserved for storage within the car.

The flight crew, honorary copilots, and guests on the mat with “559,” 31 August 1962. Concluding a 1.6-hour sortie, landing was logged at 1536. NAS Lakehurst had brought home its last airship. USN

The car was prepared for final deflation. The air and helium valves were tied off, their cables and wiring disconnected along with the flight-instrument manometer tubes. Additional ballast was added to the lower meshes of the net, and the one-million-cubic- foot envelope was “bagged down.” Now all remaining accessories were systematically disconnected. Freed from the control car, the ship’s envelope was sandbagged up again (i.e., weight removed), and the car rolled clear from beneath. Gradually, the contained helium was exhausted into and through the hangar lines to the helium plant nearby. The huge fins were detached and shunted clear of the deflating, collapsing envelope; they would be preserved separately. Helium deflation complete, the net was removed and the envelope air-inflated for entry. Inside that eerie flood-lit space, workmen detached the car’s internal suspensions and related fittings from the bag’s fabric catenaries. Ready at last for storage, the heavy envelope was rolled up, loaded onto one of the air station’s articulated “trains,” and transported to the fabric shop.

Deflation of the last airship, NAS Lakehurst, 25 September 1962. The final pressure-watch entry for “559” was recorded at 0905, 24 September. An era of naval aviation ended. USN courtesy Mrs. E. P. Moccia

Preservation of the car would conclude the process. The interior and exterior were cleared of dirt and contamination, examined, and then preserved as required. The landing gear, for example, was lubricated, tires examined, and the wheels preserved for storage inside the car. Unpainted surfaces were sprayed with inhibitor, as needed. Finally, when fully prepared for long-term storage, “559” was cocooned in airtight, vapor-proof material. Dehumidification equipment connected to the cocoon would maintain the mandatory 20 to 30 percent humidity, with temperature control also provided. Under carefully prescribed conditions, the control cars in war-reserve storage might be expected to last indefinitely. The control surfaces were hung on the hangar walls, clear of possible damage. The individual envelope kits, classified equipment, engines and allied components were stored. All deflation-and-storage activities were concluded by December. Maintenance attention for the dehumidification equipment was all that was needed now. In the event of national emergency, the United States Navy still held thirteen modern nonrigid airships in inventory, available for mobilization.

For the irrepressibly optimistic, perhaps, the 1961 termination represented an interim decision, subject to reconsideration. But the practical problems attendant to any resurrection effort were already formidable.30 The lack of an operating O&R department experienced with airships presented obvious obstacles. Nor could the backup support from the prime contractor be counted upon. In the meantime, manpower talent familiar with lighter-than-air was scattering throughout the naval service and into civilian industries. Moreover, the state of the art would not improve without an active, in-commission flight-ready program.

Sadly, the effort and expense prescribed for long-term war-reserve storage would be wasted—discarded almost immediately. The two R&D blimps had been in storage less than a month before orders were prepared to dismantle all the war-reserve airships and to salvage spare parts, support equipment, and mooring masts. Airships, it seemed, were no longer required in the United States Navy. By April 1963, a Stricken Aircraft Reclamation and Disposal Program (SARDIP) had been established “for reclamation of subject aircraft and salvage of components and equipment for use elsewhere in the Department of Defense.” The Pentagon’s Aviation Supply Office (ASO) would dispose of all spare parts into the military supply system being held for the support of the LTA program. The Industrial Office for BUWEPS in turn was made responsible for the redistribution of all excess O&R equipment and materials. The naval air station was to cooperate to realize an early and orderly closeout.

Salvage action on the stricken airships commenced in June 1963. One by one, the aircraft were removed from their storage cocoons and pulled apart. Various components and equipment were salvaged for use as spares for government aircraft. The power plants, envelopes, and collateral equipment were also reclaimed. Once all salvageable components had been stripped, the control car shells and other residual materials were released to the Defense Department’s surplus sales office through Lakehurst’s own supply department for sale as surplus government property on a competitivebid basis. Salvage activity on the thirteen airships was concluded in February 1964.

When the big-ship era had ended, scant consideration was given to its place in naval aviation history—save for its most sensational moments. During the ensuing decades, the utility of the nonrigid airship has been examined, reassessed, and explored yet again. Although the trials were hardly exhaustive, the decision against the naval nonrigid has been final. Still, some attention was given to preserving a modicum of public awareness of this fascinating if final experiment. Airship-related relics would be saved in support of both government and private museums. The control car for ZPG-2 141561—the next-to-last Navy airship to fly—was spared. In 1963, BUWEPS authorized its donation to St. Louis’s National Museum of Transport. The control car for ZPG-3W 141243 also escaped the scrap pile. Litigation in connection with the 1960 crash of sister ship 141242 was responsible, initially. Then acquisition of the eighty-three-foot car by the Smithsonian Institution was explored. But no final action on either was taken, due (in part) to problems relating to transport of the bulky gondolas to their final destinations for exhibit. So both were held at Lakehurst—unwanted vestiges of a discarded program. One control car languishes there still.

The Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association knew what it wanted, and nearly two dozen items were donated. The Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C., also received selected remnants. A small museum space was set aside in Lakehurst’s Hangar No. 1, but the space was soon reassigned and its contents discarded.

Save for discarded prototypes, no military airship has flown operationally in more than six decades. Two generations have grown to maturity with no direct association with these aircraft. The technology has been kept alive by modest commercial operations, notably that of Goodyear, Airship Industries Ltd., and, in a new century, by ZLT Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik, Friedrichshafen. Commercial activity has escalated significantly. Today, more airships fly the skies than at any time since the end of U.S. Navy lighter-than-air. But no naval airships have been built. Since their demise, there have been endless proposals, reports, symposia, and publications concerned with the revival of a military platform. Concepts have included the rigid type, the nonrigid, or blimp, and various hybrids. Serious financial commitment—always a fragile commodity for a vehicle with a public record of failure—might revive a naval application. But most proposals are oblivious to the realities of more than a half-century of neglect: loss of experienced naval personnel and know-how; the lack of significant manufacturing capability, bases, and ground support equipment; and the absence of any operational familiarity within the defense establishment itself. Skepticism and scorn persist—the long-lamented “giggle factor.” In short, an entire technology will have to be reinvented and reapplied. Despite countless studies, no group or organization has yet moved from drawing board through viable prototype to a securely funded, operational military vehicle.

[T]he constant struggle of all military systems for a share of defense resources resulted in the phase-out of all airship operations. The total “kill” of LTA was a mistake. A case can be made for removing them from the fleet, at least at that time. The total extinction by also disestablishing Airship Test and Development was the ultimate folly. This small but highly experienced and qualified unit would have cost “peanuts.” The opponents of LTA would not have it any other way. LTA was completely disestablished.31

Today, at the Lakehurst station,32 only the brooding hangars recall four decades of lighter-than-air aeronautics. But this place remains synonymous with U.S. Navy LTA. The thoughtful visitor can reflect on the experiment that was focused here. One can cross the hangar deck where Shenandoah was built and where Los Angeles was dismantled. The landing field is just outside where Akron lifted off for the last time—and where the wreckage of Hindenburg fell. Across the empty mat are the twin hangars built for the urgent days of the Second World War. From these the venerable K-ships sortied to sea on wartime patrol. Mooring circles for the big ships are long gone, but several for the postwar blimps remain, crumbling and forgotten among the scrub. Younger visitors don’t notice them, but an older generation remembers. The Navy’s lighter-than-air machines are history. And the naval aviators who flew them are long-retired—and departed. Still, they and their ships helped advance U.S. naval aviation. They should not be forgotten.