6

EMPIRE OF THE SCHOOLGIRLS

Kitty Goes Global

You learn much more about a country when things fall apart. When the tide recedes, you get to see all the stuff it leaves behind.

—TIMOTHY GEITHNER, U.S. SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY, ON JAPAN IN 1990

—EMOJI TRANSLATION

turn of the millennium. The Japanese economy is in ruins. The unemployment rate has soared beyond 15 percent, leaving millions of able-bodied citizens out of work. Disillusioned teenagers, painfully aware of the grim futures awaiting them, are in open rebellion against their parents and teachers. Desperate to prevent the sort of societal unrest that marred the sixties, the Japanese government unveils an audacious program dubbed the New Century Educational Reform Law. Every year henceforth, one graduating high school class will be selected at random and sent to a deserted island. Military encirclement prevents escape; remote-controlled explosive neckbands ensure compliance. The first class is assigned a variety of weapons and a simple set of rules: kill or be killed. The lone survivor is allowed to return, serving as both entertainment for the masses and an abject lesson to other rebellious youths. Soldiers parade the first “winner” before a mass-media scrum. Sitting in the backseat of a military jeep, dressed in a tattered school uniform and clutching a stuffed doll, is a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl. She raises her blood-spattered face to the cameras and smiles.

Such was the opening scene of the 2000 blockbuster film Battle Royale, directed by Kinji Fukasaku and based on a hugely controversial 1999 novel of the same title. (Plot sound familiar? The author of The Hunger Games swears never to have heard of the Japanese movie or novel.) Battle Royale was far from the first dystopian horror film to sweep Japan. The suffering of citizens amid the rubble of society had been a staple of Japanese entertainment from 1954’s Godzilla to the apocalyptic 1988 sci-fi anime AKIRA. Even Hayao Miyazaki, that bastion of socially conscious family-friendly fare, plumbed the topic of fallen civilizations in his breakthrough 1984 epic, Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind. But there was something distinct about Battle Royale: the schoolgirls. Some of the film’s most arresting scenes centered on the female leads, such as the scenery-chewing, knife-packing Chiaki Kuriyama, who fends off the advances of an aggressive schoolmate by stabbing him repeatedly in the crotch. The idea of plushie-clutching schoolgirls surviving a combat situation, rather than the musclebound jocks you might expect, captivated audiences both domestic and foreign. Kuriyama went on to play a similarly shocking role as a supercute schoolgirl assassin in the 2003 film Kill Bill: Volume 1, whose director, Quentin Tarantino, cites Battle Royale as his favorite movie of the new millennium.

That this dark fantasy resonated so deeply was a testament to trying times. While real-life Japan in 2000 wasn’t in nearly as bad shape as the fictional Japan of Battle Royale, the nation was in serious trouble. It had been ten years since the epic stock-market crash of December 1990. Over the next decade, Japan’s incredible postwar economic miracle sputtered, then ground to a jarring halt.

The roller coaster of financial glory and catastrophe began in September 1985, when Japan and five other nations signed an agreement called the Plaza Accord in New York. Devised by an American government desperate to remedy a trade deficit with Japan and Europe, the idea was to depreciate the dollar against other currencies so as to make U.S. exports more competitive abroad. But every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Devaluing the dollar also had the effect of making other currencies, including the yen, go further in the States. Japanese companies, riding high on what was then the world’s second-largest economy, went on a buying spree.

Rockefeller Center in New York City. The Pebble Beach Golf Club. Universal Studios. Columbia Pictures. One after the other, American icons fell into the hands of new Japanese corporate overlords. Freshly minted Japanese multimillionaires dueled in bidding wars for trophy acquisitions. Paper baron Ryoei Saito edged out another Japanese rival to pay a record-breaking $82.5 million for Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet, then sparked international fury by declaring his intention to have it cremated with him when he died. (He quickly claimed it was a joke; the painting remains safe today.) Housewives flush with cash from their salaryman husbands’ bonuses sipped on $500 cups of coffee sprinkled with gold dust. And the real estate market went absolutely wild. At its peak, frenzied speculation inflated the value of all of the land in Japan to $18 trillion, four times the value of all property in the United States. The grounds of the Imperial Palace in the heart of Tokyo, a patch of greenery just a third the size of Central Park, were valued more than all the land in California, all on their own. Nobody called it a bubble at the time. Everyone expected the good times would keep rolling on.

Even today, nobody is precisely sure why everything collapsed; there was no singular cause, but rather a complicated confluence of factors. What is certain is that the Nikkei stock index peaked in December of 1989, then began a rapid slide downward. In the fall of 1990, real estate prices followed. Organizations and individuals who had taken out massive loans suddenly found their real estate assets totally underwater, worth far less than the mortgages they had eagerly signed to pay. Businesses began going bankrupt. Corporate and individual investment ground to a halt. By 1992, when the Nikkei had plunged to just 60 percent of its peak, it was clear that there would be no return to the glory years. The economists solemnly declared that it had been a mirage—or, in financial parlance, a bubble. And the bubble had most definitely popped. Fortunes had been lost and lives had been ruined. Dreams gave way to depression, both of the financial and of the emotional varieties. Suicide rates spiked to some of the highest known in the developed world.

One of the most keenly affected was Sanrio’s Shintaro Tsuji. His firm had grown steadily throughout the years, a seeming rock amid turbulent times. Then came the crash. By September of 1990, Sanrio had lost eighteen billion yen—roughly seventy-five million dollars at the contemporary exchange rate. “Stock-Crazed Rogue CEO Drives Sanrio Deep into Red,” trumpeted one magazine headline—a shocking comeuppance. It turned out that Tsuji had been engaging in a popular form of financial speculation the Japanese called zaiteku, a bubble buzzword among the executive class meaning “financial engineering.” As many a Japanese CEO had, Tsuji plowed his firm’s cash reserves into stocks, real estate trusts, and other high-risk, high-return corporate investment schemes. During the bubble this risky strategy had paid off handsomely; for a time, Tsuji’s profits from trading exceeded Sanrio’s income from its products and licenses. Emboldened, he launched an audacious plan to build a Sanrio theme park, to be called Puroland, on the outskirts of Tokyo. But as the stock market crumbled, so did Tsuji’s positions. Almost overnight, the firm Tsuji had painstakingly built over decades lost 90 percent of its value. “I couldn’t sleep without sleeping pills,” he confided in his memoir. At one point, he even contemplated suicide.

These were dark times indeed. Amid real-life economic dystopia, Japanese youth turned increasingly inward toward fantasy, fueling the rise of new cultures and subcultures: the growing embrace of video gaming as a mainstream leisure activity; the appearance of wild fashions and elaborate cosplay in public spaces; the proliferation of mass gatherings for those who embraced anime and manga less as entertainment than as a lifestyle. Yet there was no better image of survival than that of the Japanese schoolgirl. Using every tool at her disposal, young women transformed themselves, Sailor Moon–style, into tastemakers who blazed a path for Japan through the Lost Decades. Salarymen built Japan, Inc. As it crumbled around them, young women picked up the pieces. They re-envisioned adulthood by unabashedly consuming things they were traditionally expected to abandon as they grew up, from girls’ comics to Sanrio products. In embracing emerging new technologies far earlier than cautious grown-ups, they almost single-handedly upended entire industries. The karaoke scene was the first to be so disrupted, followed closely by the music industry as a whole. Then, as schoolgirls threw themselves into newly developing forms of digital communications, they recast a host of cutting-edge technologies into tools better suited to this strange new era. Text messaging; the perfection of the online “language” of emoji; even, arguably, the foundations of social media. A great many things we global citizens take for granted in our constantly connected digital lives were pioneered by schoolgirls on the streets of Tokyo.

Their appearance on the scene heralded a dramatic societal shift. Consumers were evolving from passive recipients of the things makers gave them into a new sort of creative collective in their own right. Men and their factories made Japan an economic tiger; now, in the 1990s, girls were recasting Japan as a cultural superpower in their own image. And they did it under the Jolly Roger of another feline: Hello Kitty.

charge of Hello Kitty in 1980 at the age of twenty-five, Sanrio’s Yuko Yamaguchi spent the next fifteen years re-envisioning both the character and herself. The ambitious young graphic designer had joined the company in hopes of forging opportunities that didn’t exist for women in mainstream Japanese companies. She found them, but—wait a second. Fifteen years? What was a (gasp!!) forty-year-old woman still doing at Sanrio, the company that ushered women out the door the moment they married? Times had changed, that’s what.

Yamaguchi found opportunity aplenty within the bailiwick of design at Sanrio, but quietly fumed about the company’s cavalier attitude toward retaining its female talent. On the surface, everything looked great. Sanrio’s female staff weren’t forced to serve tea to the men as they were at other big Japanese companies of the day (or, at least, not after their first year or two). And once they established themselves, they were given great latitude to propose designs or manage product lines or handle whatever their specialty might have been. But that relative freedom didn’t translate to upward mobility in the ranks of the company. Over the years, Yamaguchi watched talented woman after woman quit out of frustration. Eventually she had had enough. A few years after taking charge of Kitty, she marched into a managing director’s office and told him that if the company didn’t start moving qualified female staff into managerial roles, she’d quit on the spot. The tactic worked. Shortly thereafter, all the women who’d been there longer than her suddenly got promotions. And by the mid-nineties, Yamaguchi was no longer simply Kitty’s designer. She was the manager for a two-dimensional talent, the flesh-and-blood oracle for a voiceless kitty-girl.

Dyeing her hair with shocking pink highlights and often wearing vividly patterned baby-doll dresses, Yamaguchi toured the country relentlessly. Her destination was inevitably one of Sanrio’s Gift Gates, of which there were now more than a thousand operating in Japan, steadfastly maintained even amid the financial apocalypse unfolding at Sanrio HQ. There she would sit at a table and interact with young Kitty consumers. The events started simply as a form of PR outreach. Over the years they developed into something more: a way for Yamaguchi to observe trends among Kitty’s fans in real time, helping her keep the character fresh in the face of constantly evolving tastes. In many ways she was a celebrity in her own right, at least among those who loved Sanrio’s products.

Thanks to these events, Yamaguchi had already noticed a subtle aging up of Kitty’s traditional demographic. Like all Sanrio’s mascots to that point, Hello Kitty was created to appeal to kindergarten and elementary school girls. That is who had supported her during the boom of the late seventies and a subsequent one in the mid-eighties. But as the nineties rolled around, junior and senior high schoolers began appearing amid the little girls and mothers who had traditionally formed the bulk of the participants at Yamaguchi’s sessions. Raised on Kitty, they either refused to graduate from this childhood pleasure as they aged or returned to her as older girls. So it wasn’t particularly shocking to see a group of high schoolers standing in front of her table one afternoon in 1995, as she recounted in her memoir Tears of Kitty.

Something about these teens was different. They wore sailor suits, the style of uniform seen in high schools throughout Japan: white blouse adorned with a wide blue collar, red neckerchief, blue pleated skirt, and knee socks with loafers. But these weren’t standard issue—they had been subtly modified. Their ruzu sokkusu (“loose socks”), as the style was known, were thick and puffy as legwarmers, sagging around the ankles and pooling over their shoes like wax dripping from a candle. The skirts had been shortened enough that you could practically see the curves of the girls’ backsides. Yamaguchi recognized the look. These were the much-rumored kogyaru—“kogals.” Teen slang for “high school gals,” they were fashion-obsessed delinquents from the streets of Shibuya, where all the cool kids in Tokyo and everywhere else in Japan aspired to hang out. The kogals were essentially version 2.0 of the gyaru, those party girls of the glitzy bubble years. The party was long over, but the new generation kogals hungered for the same Burberry scarves and Vuitton handbags they’d seen their older sisters flaunting during those epic eighties boom days. The problem was that there wasn’t much money to go around anymore.

Shibuya was located adjacent to Tokyo’s fashion district of Harajuku. It was a grubbier, lower-rent, teen-focused hangout, packed with bars, fast-food chains and cheap ramen joints, fifty-yen (as opposed to the usual hundred-yen) video game arcades, karaoke boxes, and department stores specializing in low-cost cosmetics and faux-bling accessories. In short, everything a schoolgirl needed to strut her stuff down Center Street, Shibuya’s main drag, the neon-lit, graffiti-tagged urban canyon at the heart of the neighborhood—all of it bathed in the redolent aroma of cigarette smoke, shallow sewers, and stale beer from the piles of empties growing on the curbs outside the all-night convienence stores.

Yamaguchi had seen the three earlier, talking among themselves before the event had started. When the designer walked by, she’d overheard a phrase that sent a shiver down her spine: enko. Short for enjo kosai. It meant “compensated dating.”

The word was all anyone was talking about that year. There’d been a series of articles about it in the popular news weekly Shukan Bunshun. Investigative reporter Katsushi Kuronuma scandalized society with an exposé of an underworld of dating services that charged men a fee to browse voice messages left by potential partners. Although they were officially intended as a matchmaking service for grown-ups, a subset of teens realized that these “telephone clubs” provided access to wealthy men. Young girls coveting status symbols left messages offering companionship by the hour in exchange for designer bags or expensive jeans, often specified down to the color and size.

Sometimes it really was just companionship in the form of a dinner out on the town. Other times it went further. This wasn’t called prostitution, a label all parties desperately wanted to avoid. Instead it was euphemistically referred to as enjo kosai. Kuronuma’s piece had been straightforward investigative journalism, but once the story broke, the tabloids had a field day with the image of Hermès-hungry schoolgirls flaunting themselves to horny, hard-up salarymen. Those same salacious headlines provided other girls with a template for imitation, fueling behavior that was picked up again by reporters hungry for titillating content. It was a vicious cycle.

Yamaguchi sat at her table, her arms around a large Hello Kitty plushie, trying to figure out something to say to them. The girls stood quietly before her in their heavy makeup and micro-miniskirts, waiting for autographs. Yamaguchi wanted to yell at them, to tell them she’d heard, to tell them to stop. Instead she found herself blurting out a question she never dreamed she’d be asking, let alone with a Hello Kitty in her lap.

“Why do you sell yourself to men?”

The question hung in the air for a moment. Yamaguchi suspected they thought Kitty herself had asked it. The girls didn’t make eye contact. Finally, one of them broke the silence.

“Because I want a name-brand wallet. They’re made of cool materials. They’re kawaii.”

Yamaguchi thought this over for a moment. Then she made a proposal: She’d make a Kitty wallet just for them. It would be pink, and finished just like an expensive brand. But it would feature Kitty, and be priced right, so nobody would have to do anything weird to buy one. The girls’ faces lit up.

The wallet debuted in 1996, together with a host of other accessories: a handbag, a cellphone holder, a coin purse. They were made out of quilted faux leather in a pastel pink. They didn’t look anything like that first Petit Purse of decades earlier, cheap and designed for tiny hands. They looked like something a big fashion brand might make, with one big exception: Right where you might expect some famous logo was Kitty’s placid face.

So many of Yamaguchi’s grown-up Kitty accessories sold in 1996 that she literally flipped the firm’s fortunes, improbably converting a projected 340-million-yen loss into a 2.8-billion-yen profit. The new fashion line tapped into something no one, not even Kitty’s manager herself, had imagined existed: a latent demand for elementary school characters among the teens and even grown women of Japan. Eighties gals had craved glamour and sophistication. The kogals of the nineties craved it, too—but recast in the comforting form of a fondly remembered icon from their childhoods, one that could also serve as an unspoken visual code for bringing like-minded friends together. Years later, the journalist Kazuma Yamane would call this new evolution of fancy goods “communication cosmetics.”

Looking back, it makes perfect sense: a fantasy of having your cake and eating it, too, basking in a childhood pleasure while still looking stylish enough for a grown-up night on the town (or at least an afternoon out on Shibuya’s Center Street). Left unsaid in all the media coverage—and the surprise at Sanrio’s unexpected resurrection from the financial dead—was the fact that it never would have happened save for Yamaguchi’s chance encounter with a clique of schoolgirls seeking sugar daddies.

aspired to sugar daddy relationships, of course; despite media hype to the contrary, “compensated dating” remained firmly on the fringes of polite society. For the average Japanese teen, as for the average Western one, it was the rock star who occupied a central role in their leisure and fantasy lives.

It is 1996, and the king and queen of Japanese pop are on a date. He is the multimillion-selling superproducer Tetsuya Komuro. She is his protégé and star of the moment, the vocalist Tomomi Kahara. Already popular when she met Komuro, with him she recorded her first solo album, Love Brace. Just a week after it was released, in June of 1996, it sold a million copies. Now the pair are celebrating with a date on the town, documented by the eager cameras of the country’s most popular music show, Utaban. Will the pair pick a fancy restaurant and open a bottle of champagne? A night out at one of Tokyo’s famed discothèques, bathed in lights and adulation? Perhaps a romantic retreat at one of the city’s upscale hotels?

None of the above. The twenty-two-year-old Kahara has insisted her boyfriend take her to Sanrio Puroland.

Almost complete when Sanrio announced their horrific losses in the stock market in the fall of 1990, the theme park opened in December of the same year. Incorporating input from designers who had worked on attractions for Universal and Disney, Tsuji envisioned Puroland as “a land of love and dreams,” a pastel wonderland for elementary school girls, complete with simple rides, stage shows, actors clad in Sanrio mascot suits, and of course numerous gift shops. Initially, it was a costly failure. Already far smaller in size than its intended rival, Tokyo Disneyland, which opened in 1983, it was also by nature more tailored to the tastes of little girls—further limiting the pool of customers. The park hemorrhaged money for the first three years of its existence; critics derided it as “an expensive box,” all packaging and no substance, a true low blow in a nation as serious about presentation as Japan. Tsuji began tweaking the shows and attractions to better suit a broad spectrum of tastes—or perhaps his own personal ones. “If the dancers aren’t sexy, fathers won’t come to see the show,” he explained matter-of-factly to American journalists. “We can’t do dirty shows or show breasts, but we can show thongs.” Finally the park began turning a modest profit. But in truth, it wasn’t because of thongs or fathers. It was because of teenagers and young women. Women like Kahara.

As the cameras roll, the young, presumably fabulously wealthy vocalist strolls arm in arm with an actor in a furry, life-size Hello Kitty costume. Then she raids the gift shop and fills basket after pink basket with seemingly every Sanrio product ever made. Stationery. Housewares. Enormous plush dolls. All of it goes into a series of giant plastic bags that are hustled out by a coterie of black-suited handlers like kawaii bagmen. Although Kahara is a seemingly healthy, grown woman, her every utterance, her every gesticulation, is made in the manner of an overstimulated preschooler: knees bouncing, arms swinging, making little squeaks and bunny hops out of sheer excitement. Onstage, Kahara is a formidable presence: focused, driven, delivering love songs in a voice high pitched but well within adult register. Here in public, however, she is kawaii personified: a flesh-and-blood version of the products on the shelves. Whether she’s putting on an act or simply someone in touch with her inner child, the rift between the two personas is jarring. A grown woman at the peak of her artistic powers behaving like an overgrown toddler was at odds with the perception of a diva—at least compared to the global trendsetters of the day, sultry Western singers such as Madonna, Celine Dion, or Toni Braxton.

Or was it? There’s something about Kahara’s performance at Puroland that is oddly reminiscent of a certain group of femme fatales from the early nineties: the riot grrrls, a very loose collective of all-girl bands that emerged in the era of grunge. These lo-fi pioneers, who orbited around a punk group named Bikini Kill, heralded a new constellation of female talent who sang for themselves instead of the boys. In an era that was dominated by aging arena rockers, graying hair-metalists, and nihilistic grunge acts, the grrrls injected a breath of fresh air into the American rock scene.

Superficially, of course, a riot grrrl couldn’t be more different from a kawaii Japanese idol. Grrrls were raw, ironic, aggressive, anti-cute. Idols like Kahara were (and are) carefully managed, plastic and comforting. Yet the riot grrrls were no strangers to childhood imagery themselves. Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna often performed in barrettes and pigtails; Babes in Toyland deployed literal dolls in their videos; Courtney Love dressed in tattered baby-doll dresses while screaming ragged songs about abuse and sexism. Ignoring the message of empowerment in favor of the titillating presentation, sexist critics derided the look as “kinderwhore” and the riot grrrls as perpetually aggrieved man haters. What they really were was a jolt to the establishment of the traditionally testosterone-saturated industry of rock and roll. Kogals, dressed in their own versions of kinderwhore outfits, defiantly refusing to give up their childhood pleasures, and squeezing pocket money out of salarymen, represented much the same to Japan on a society-wide scale. And Kahara in particular, who whiplashed between sexy singer onstage and overgrown preschooler openly declaring love for Hello Kitty on prime-time network television, almost single-handedly made kiddie stuff cool for a new generation of teenage fans.

Kogals weren’t countercultural rebels in the sense of the student protesters of a generation earlier, nor were they punks flipping a finger at polite society. They chipped away at the foundations of a male-dominated consumer culture in a passive way, simply by consuming the products they liked. This proved surprisingly disruptive—even more so, arguably, than the efforts of the riot grrrls. One of the first major businesses to be turned on its head by schoolgirl sensibilities was the karaoke industry, long the realm of the salarymen who crooned in the smoky companionship of by-the-hour hostess clubs. In the early nineties, girls flipped the karaoke demographic from old and male to young and female virtually overnight. As a result, both karaoke and the entire Japanese music industry would come to revolve around their tastes.

This sea change wasn’t anything that could have been planned or predicted. It was the unexpected result of a new technology: digitized, streaming karaoke on demand. Storage had always been a problem for karaoke; formats changed quickly, and it cost a fortune to update one’s collection of 8-track tapes into cassettes or CDs. For a while—roughly, the late eighties into the early nineties—laserdiscs reigned as the ultimate karaoke delivery system. They looked like overgrown DVDs: gleaming silver platters the size of a vinyl record. Although the medium was analog rather than digital, laserdiscs worked pretty much like DVDs. They stored music and videos, and allowed users to skip from track to track at the press of a button. The largest laserdisc “carousels” were contraptions the size of refrigerators, accommodating as many as 144 of the platter-like discs—throwbacks to the jukebox era of musical furniture. Yet even this wasn’t enough to keep up with the constantly expanding catalog of pop music, for it took months to license, master, press, and distribute a CD or laserdisc. For most of karaoke’s early existence, there was no way to sing a recent hit.

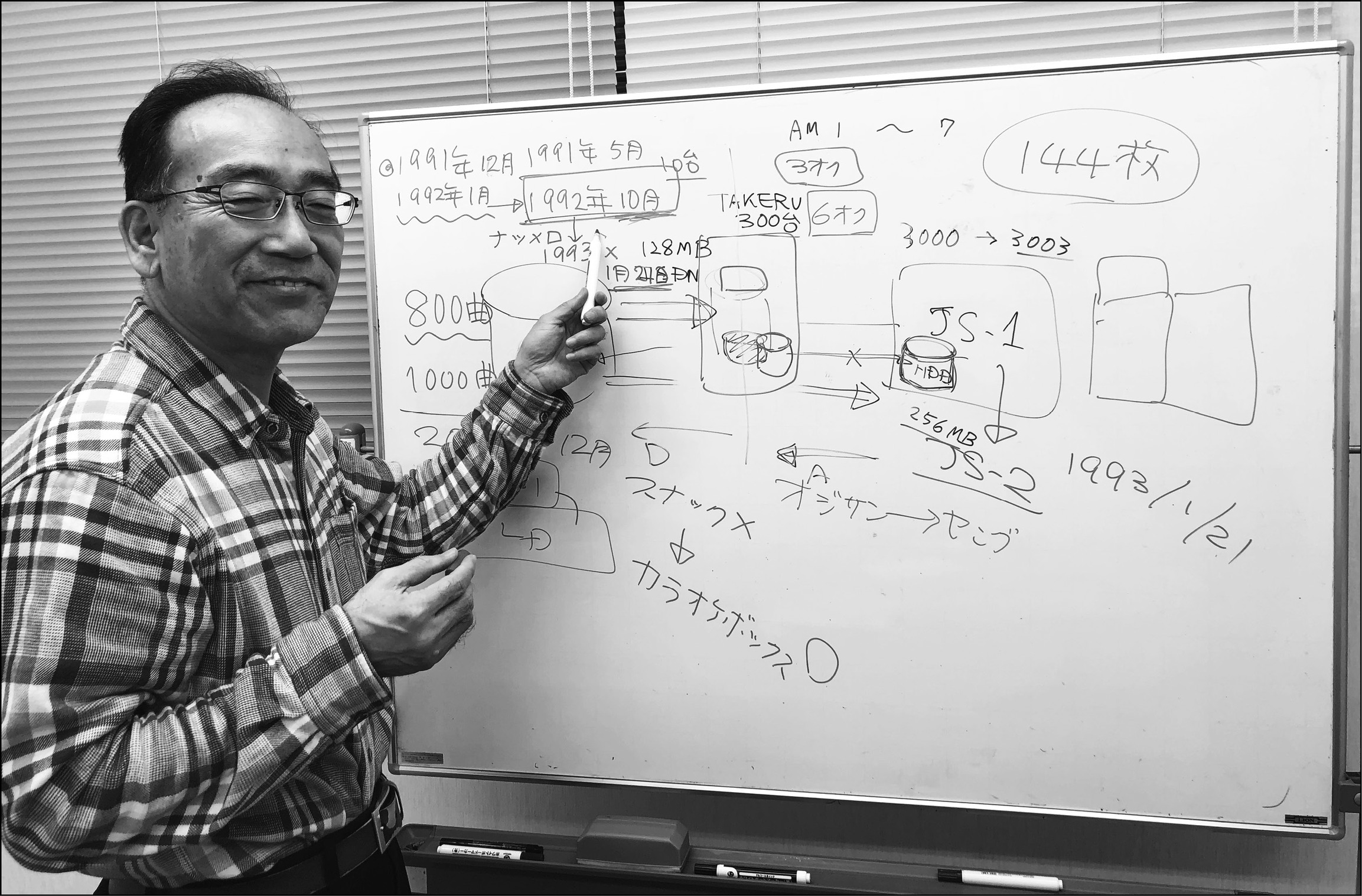

The fix for this problem wasn’t exactly rocket science, but it was close. It was the creation of a plasma physicist by the name of Yuichi Yasutomo. His invention of tsushin karaoke (literally, “communication karaoke,” or in more modern parlance “streaming karaoke”) in 1992 inaugurated the world’s first truly popular digital music-delivery service. Originally intended for karaoke pubs and their middle-aged patrons, it took off among teenagers instead, a trend that would profoundly shift the Japanese pop music scene as a whole. Ironically, the invention was created by someone without much of an interest in karaoke at all.

“I never, ever sing,” Dr. Yasutomo says in the meeting room of his downtown Nagoya office. Long since retired from the industry, he coaches start-ups in a tech incubator. “The only time you’ll see me with a mic in my hand is if someone tricks me into it. Sorry.” A low talker with a wry, self-deprecating sense of humor, he grows visibly excited as he sketches out the schematics for his karaoke-on-demand system on a whiteboard for me. “I never made anything off this beyond my base salary,” he says, laughing as he draws. “My wife is always like, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ ”

Plasma physics and karaoke seem an unlikely match, but by the eighties, karaoke was a huge business. In much the same way that pornography spurred the development of its own host of communication technologies in the United States—the Polaroid camera, the VCR, cable TV, paid telephone services, and the Internet all owe their widespread adoption in part to the popularity of smut—Japan’s karaoke industry spurred the development of audio-video technology there. This was particularly true for storage media and content-delivery systems, with increasingly high-capacity formats capable of serving up as many songs to customers as quickly as possible. But karaoke’s influence could be felt outside of the music industry as well. The earliest incarnation of Nintendo’s Family Computer, or Famicom, precursor of the Nintendo Entertainment System—incorporated a microphone into one of its control pads in anticipation of software companies releasing karaoke cartridges; and without karaoke we’d likely never have seen the Sony PlayStation, either. Sony’s executives, reluctant to commit the vast sums of money required to compete in the ferocious home video game “console wars” of the 1990s, only gave it the green light because they believed as many or more customers would purchase the consoles as singing machines as they did for gaming.

Yasutomo was long interested in computers, which he used extensively in the course of his physics studies. After completing his PhD, he joined a Nagoya-based printer manufacturer (formerly a sewing machine company) by the name of Brother. His first project was designing for them a vending machine for software. A nationwide network of TAKERU kiosks allowed users to download programs to floppy disks, saving software companies the cost of manufacturing, storing, and distributing packages. They were, in effect, like websites you had to physically visit. But this was far ahead of the curve, and Brother had a hard time turning a profit. So Yasutomo came up with the idea of giving the machines a double life. By day they would vend software as usual. But after hours, once the computer shops closed, the machines would quietly transform into karaoke servers, using modems and telephone lines to reach out across Japan and serve up the latest crop of songs to yet-to-be-developed digital karaoke machines. Theoretically, any bar, coffee shop, or karaoke room that purchased one of them would never have to purchase physical media ever again.

Emphasis on the “theoretical.” Today we take the digital distribution of all sorts of content for granted, but this was long before the Internet made such things part of daily life. It was all the more remarkable for the technology of the day. Thanks to the limited capacity of telephone lines, Yasutomo couldn’t transmit actual digital recordings. Instead, the songs would need to be rendered in a computer format called MIDI, which was like digital sheet music. A MIDI file wasn’t a song itself but rather instructions for a computer to synthesize it locally. Unfortunately, MIDI didn’t sound anywhere near as good as an actual recording, and a lot of people thought his system was crazy. (“What is this plinky-sounding shit?” thundered a karaoke executive to whom Yasutomo demoed the system.) Nor was the system capable of serving anything beyond the music and lyrics—there would be no accompanying videos, as had become commonplace in laserdisc-equipped clubs. It was all about convenience; once a song was digitized, it could essentially be distributed to any and every computerized karaoke machine instantly.

Another tiny problem: The songs would need to be rendered into MIDI format by hand—thousands upon thousands of them. Undaunted, Yasutomo hired a hundred data-entry specialists, forty of them kids from a local college of music. Hunched over their keyboards, wearing earphones, the team members listened to songs, entering the music into their computers bar by bar. It was slow, tedious work. There were no apps or tools to assist them. The start-and-stop process of listening to a snippet of a song, transcribing it into MIDI, listening to the output, and correcting the code meant even a simple song might take a week to process. More complicated tunes could take a month. Altogether, the effort took a year and a half of round-the-clock data entry. It cost Brother six hundred million yen—close to five million U.S. dollars at the time. It also cost Yasutomo his high-frequency hearing range, wiped out by countless hours spent listening to plinky-sounding songs as he managed the entire process.

The first version of his streaming karaoke machine arrived in 1992. The middle-aged enka crowd, crooning old-school ballads on those gleaming laserdiscs in their hostess clubs, could have cared less, and Brother had a hard time convincing many outlets to purchase their new streaming karaoke machine. It was the second edition, released a year later in 1993, that really changed the narrative. The reason was simple. Instead of the enka standards preferred by karaoke’s traditional middle-aged fan base, Yasutomo followed the advice of younger assistants and packed the database with up-to-the-minute hits from the J-pop charts instead.

Suddenly, queues formed outside karaoke boxes advertising his machines. The kids didn’t care that the music sounded plinky; it was their music. Finally, they could sing the songs they wanted to sing. Within two years, more than 60 percent of karaoke venues shifted from discs to streaming systems made by Brother and its rivals. But something even bigger than market share was at play.

Streaming karaoke machines tracked every song that consumers chose to sing, as they were being sung. The ostensible reason for this was tallying playbacks for calculating royalties, but it also transformed each participant’s selection of song into a vote. No longer was a karaoke song a shout into the void. Very quickly, record labels realized that they could use the royalty data to play “moneyball,” sifting through to see what kind of song worked best with what kind of singer, what kind of songs resulted in hits. Depending on how granular your report was, you could even make predictions about who was singing based on demographics. If you knew a machine was located in a love hotel, for example, and a creaky old enka song was followed by a teen idol song, you could be pretty sure some “compensated dating” was going on.

So it happened that Yasutomo accidentally invented “big data for music,” as he now calls it. Before on-demand karaoke, only a handful of Japanese singles had ever sold a million copies. After its debut, ten such hits appeared in 1993. Two years later, the number had risen to twenty. Twenty million–selling songs a year! In the United Kingdom, by comparison, only twenty-six singles sold a million copies during the entirety of the nineties. This was unprecedented stuff for any nation’s music industry, let alone one supposedly in the midst of a hideous economic recession. And it was all thanks to karaoke—or more precisely, to the young people eagerly incorporating it into their social lives.

Schoolgirls were among streaming karaoke’s most avid early adopters. It was a cheap social activity and a way to connect with their idols—divas like the Kitty-obsessed Kahara. In fact, in many ways, she owed her career to streaming karaoke. Her boyfriend/producer Komuro was one of the first to realize that networked karaoke machines weren’t simply music dispensers. They represented a direct line into the hearts of young fans. To the incoming data from thousands of Yasutomo’s karaoke machines he and his label, Avex, added on-the-street surveys and focus groups of high school girls. They used it to guide them in everything from what sort of singles to cut to the lyrics of the songs to the very outfits that the performers would wear onstage. What young fans wanted, it became clear, were idols who looked and sounded a lot like them. In the West, it was punk rockers armed with elemental chords who tore down the invisible walls between pro and amateur, between creator and consumer. In Japan, it was schoolgirls and streaming karaoke. Singability began affecting the songwriting process before a single note was even laid down in the studio. As far back as the seventies, the hiki-katari sing-along artists realized that karaoke would eat their lunch. They’d been right about that, but nobody could have imagined that it might eat into the careers of professionally trained singers, too.

As J-pop artists came to be selected not by inherent talent but rather the ability of the average schoolgirl or schoolboy to mimic them, squeaky-cute vocalists like Kahara and wholesome boy bands with names like SMAP, Tokio, and Arashi displaced traditional rockers and vocalists on the pop charts. This arrangement made fortunes for karaoke-savvy kingmakers like Komuro. “You don’t always need to be number one,” opened SMAP’s massive 2003 hit, “The One and Only Flower in the World.” It was intended as sonic comfort food, a song of love and acceptance, but they might as well have been singing about Japan, slogging through a recession so prolonged that some were beginning to wonder if it might ever lift.

was the roughest yet. In January, an earthquake leveled large parts of the city of Kobe. The government so thoroughly dithered its response, waiting more than seventy-two hours to dispatch Self-Defense Force rescue crews to help, that a local yakuza gang stepped in to distribute food and supplies to trapped citizens. Just a few months later, in March, an apocalyptic death cult called Aum Supreme Truth released handmade nerve gas in a crowded Tokyo subway station. The terrorist attack killed thirteen, grievously injured fifty, and sickened a thousand more. Taken together, the incidents raised disturbing questions about just who, if anyone, was really in charge anymore.

The backbone of Japan’s domestic and export consumer economy—high-tech manufacturers such as Hitachi, Toshiba, Mitsubishi, and NEC—were shedding catastrophic amounts of market share to Asian rivals. When President Bill Clinton made a trip to Asia in 1998, something happened that would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier: He skipped Tokyo. As American political and business leaders eagerly turned their gaze to newly ascendant China and South Korea, the same Japanese politicians who had railed against Japan bashing began fretting about what they called “Japan passing.”

Prolonged economic unease had a profound effect on young citizens, and the mass media eagerly chronicled a perceived crumbling of society. Terms like hikikomori (a coinage for young shut-ins who refuse to attend school or even leave their homes) and gakkyu hokai (“classroom chaos”) entered the popular lexicon. College grads, both male and female, desperately cast about for jobs in the midst of a hiring freeze so pronounced that it is now called shushoku hyogaki—the Ice Age of Employment. Many millions never launched careers at all. The kids, it seemed, weren’t all right.

It felt like everything had gone topsy-turvy, that a once-great nation was coming apart at the seams. Unable to attain the milestones of adulthood, Japan’s youth increasingly turned from mainstream culture to subcultures. Increasing numbers of young men and women immersed themselves in vibrant fantasy worlds, fashioning new identities for themselves as super-connoisseurs of manga, video games, and anime. The most striking changes, and the ones with the most global impact, played out in Tokyo’s fashion centers of Shibuya and Harajuku, where schoolgirls and young women fashioned new identities and forged new styles of communication. Among their tools were text-capable pocket pagers, mobile phones, and access to one of the world’s earliest mobile Internet providers. Grumpy grown-up critics framed these endeavors as a shirking of responsibility, an infantilization of a once-proud society, a great dropping out. But those in the thick of it knew they were plugging in to something new.

Interconnected like never before, sophisticated young consumers with an unceasing hunger to connect formed new social networks that transformed Japan’s city streets into petri dishes for cultural innovation. In an economy bloodied by the burst of the bubble, the nerds and the schoolgirls were the last consumers standing. Battle Royale may have been fiction, but maybe only by a little bit.

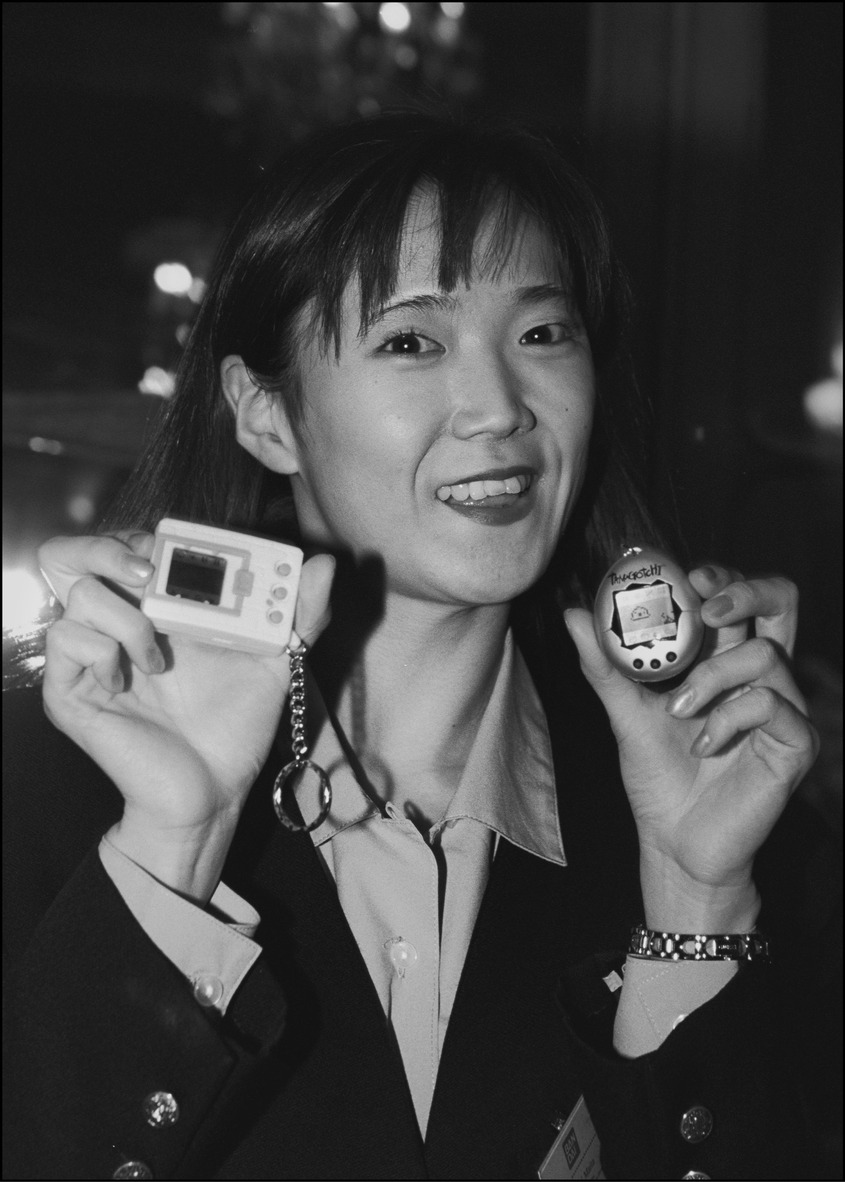

of 1996, fifty-one years almost to the day after Kosuge’s jeep went on sale in Kyoto, a strange new product appeared in Tokyo. It captured the zeitgeist in much the same way that Kosuge’s scrap-tin jeeps had, and thousands queued up outside of Japan’s many toy shops for their chance to own one of the prized new playthings. This time, however, the toy wasn’t made of junk. In many ways it represented the cutting edge of electronic engineering: a silicon computer chip driving a postage stamp–sized mini liquid crystal display, these high-tech innards sheathed in a colorful plastic housing designed to appeal to schoolgirls. It was called the Tamagotchi.

A portmanteau of the Japanese words tamago (egg) and uocchi (watch), the palm-sized electronic Tamagotchi resembled a portable video game, but the point wasn’t beating a puzzle or fighting enemy invaders. On a miniature black-and-white screen “lived” a tiny blob that demanded continuous attention, just like a real critter. If properly fed, watered, and cleaned up after—they “pooped” just like real critters, too—a Tamagotchi would “grow” through a series of phases into an adult, its final appearance, attitude, and constitution depending on just how you nurtured it through infancy and adolescence. The trick was that there was no Off button. From the moment you removed your Tamagotchi from the package, you were responsible for the life of this tiny digital creature, beholden to its beeps for attention and sustenance. If you left it alone for too long at any point, for any reason, it would wither and die, its expiration marked by the pathetic scene of a ghost hovering over a tiny pixelated grave.

Defecation and death don’t exactly sound like a recipe for good times, let alone a hit product. But entrepreneur Akihiro Yokoi felt otherwise. The idea for the toy came to him early in 1995. A former employee of the toy giant Bandai, he ran a design company called Wiz. Like Kosuge’s tin-toy studio decades earlier, Yokoi’s firm didn’t actually sell toys; it sold ideas for them to bigger manufacturers, chief among them his former employer. Yokoi’s latest emerged from his love for animals. He kept cats, dogs, and a parrot at home, and the centerpiece of the Wiz offices was a three-hundred-gallon saltwater tank filled with exotic tropical fish. What he hated was leaving them behind whenever he had to travel. The Tamagotchi, as he and his staff developed the idea over the next few months, was a pet that you could carry with you anywhere, anytime, in the form of a specially designed gadget—caring for it from egg to adulthood.

His collaborator was Aki Maita. She was a thirty-year-old Bandai marketing specialist when Yokoi’s proposal came across her desk in the summer of 1995. It featured a cartoon of a man leaping into action with the Tamagotchi strapped to his wrist. Another illustration set the Tamagotchi atop a stand, flanked by a little figure of a caveman. These were decidedly boyish fantasies. Maita loved the idea but thought the proposal appealed to the wrong audience. She thought it should be fancified for little girls. After many meetings, Yokoi and Maita’s teams began refining the design of the toy.

To keep costs down, a Tamagotchi’s screen had to be tiny: a little rectangle just sixteen by thirty-two pixels. The bobbly-head-tiny-body philosophy that gave rise to Kitty and Mario had the power to breathe life into the barest of design elements. But kawaii alone was old hat now. Yokoi cast about for something fresh and new. Flipping through girls’ fashion magazines for inspiration, he noticed something interesting. A lot of the illustrations in their pages were deliberately primitive. They looked less like graphic design and more like something the parent of a preschooler might proudly display on their refrigerator. He’d seen this kind of thing before, usually deployed in four-panel comedy manga, but it seemed to have become the default graphic style of the girls’ magazines. Aficionados called practitioners of the style heta-uma—really good at drawing badly. Hello Kitty was cute, but so too was she a slick piece of graphic design. Ditto for Mario, refined from his blocky origins into a clearly defined cartoon character as game technology improved over subsequent sequels. Part of the charm of heta-uma characters was that they looked like something consumers might actually doodle themselves.

But heta-uma in fact took a great deal of skill to pull off. Yokoi convened an in-house talent competition similar to the one Sanrio had used to determine Kitty’s manager in 1980. The winning illustration came out of nowhere, from a freshly hired designer named Yoko Shirotsubaki. Then twenty-five, she was only a little older than the schoolgirls whom the product was designed to target. She’d managed to change jobs some thirty times in the four years between graduating from art school and landing at Wiz, dabbling in everything from retail sales to waitressing at a lesbian bar in Kabukicho, Tokyo’s red-light district. Her vision of the Tamagotchi was even more stripped down than Mario or Kitty. It looked like something the famed eighteenth-century biological taxonomist Carl Linnaeus might have drawn had he worked for Sanrio, an evolutionary tree of little blobs that Shirotsubaki had managed to clearly differentiate using only the vaguest of features: dashes or dots for eyes, some with tiny ears, or the hint of what seemed to be a beak—or were those lips? Was that one a starfish? Or some kind of one-eared bunny? They were deeply weird yet instantly recognizable at the same time.

Now that they had their characters, all that remained was to perfect the Tamagotchi’s external appearance. For this, Maita and her co-workers began canvassing the streets with mock-ups of plastic shells, inviting passing kogals to comment on which shapes and colors they liked best. Their first destination was Harajuku, the city’s fashion district. Located just one stop away from Shibuya, where the kogals congregated, Harajuku’s high-end boutiques radiated an aspirational sophistication, making it a sort of Oz for schoolgirls. The neighborhood’s main drag of Omotesando Boulevard, lined with towering ornamental zelkova trees, was and is home to the flagship outlets of Chanel, Hermès, and the other foreign luxury brands they so coveted. But the real heart and soul of Harajuku lurked just out of sight, behind the façades of high fashion.

In contrast to the bling of Omotesando’s boutiques, Harajuku’s backstreets were a twisting maze of alleys and dead ends. The most famous was Takeshita Street, a sort of urban boardwalk where tiny shops hawked cheap fashions, sugary foods, and posters of pop singers from around the world to eager teens. As one penetrated deeper into the labyrinth, the luxurious foreign influence evaporated. In its place one could bathe in a strange aura from countless tiny domestic boutiques that supplied seemingly bizarre accessories to the tiniest of niches. Within the confines of what everyone called Ura-Harajuku—the “Harajuku underground”—even the meekest of classroom dwellers were empowered to reimagine themselves in a riot of ever-changing identities, from beach Barbie gals in thick platform heels to black, frilly Gothic Lolitas who resembled Alice in Wonderland after a homestay with The Addams Family. So too the boys, in fashions ranging from fifties greasers in denim and leather to androgynous Visual-kei glam rockers decked out in fabulous sequins and Dragon Ball–style hair. So transformed, they bided their time for the weekends, when fashion freaks from all over Japan poured in to dance in the streets that were closed off to traffic. Harajuku was more than a neighborhood. It was a state of mind.

In other words, this was the perfect crowd upon which to test something as weird as the Tamagotchi. At the peak of Japan’s summer season in August, Bandai employees canvassed the streets of Harajuku and Shibuya for as many young women as they could get to respond—from middle schoolers to office workers—showing them mock-ups of potential Tamagotchi housings. Some were circular, others rectangular, still others oval. Over subsequent rounds of survey and modifications, an egg shape emerged as the most popular. Maita knew they were on the right track when girls finally began asking if they could keep the colorful samples. The Tamagotchi was almost ready to leave the nest. But these surveys merely identified whether respondents thought the product’s exterior looked cute or not. Nobody knew if customers would actually pay money to clean up digital pet poop. For the answer to that heretofore never-contemplated question, they could only release the product and wait.

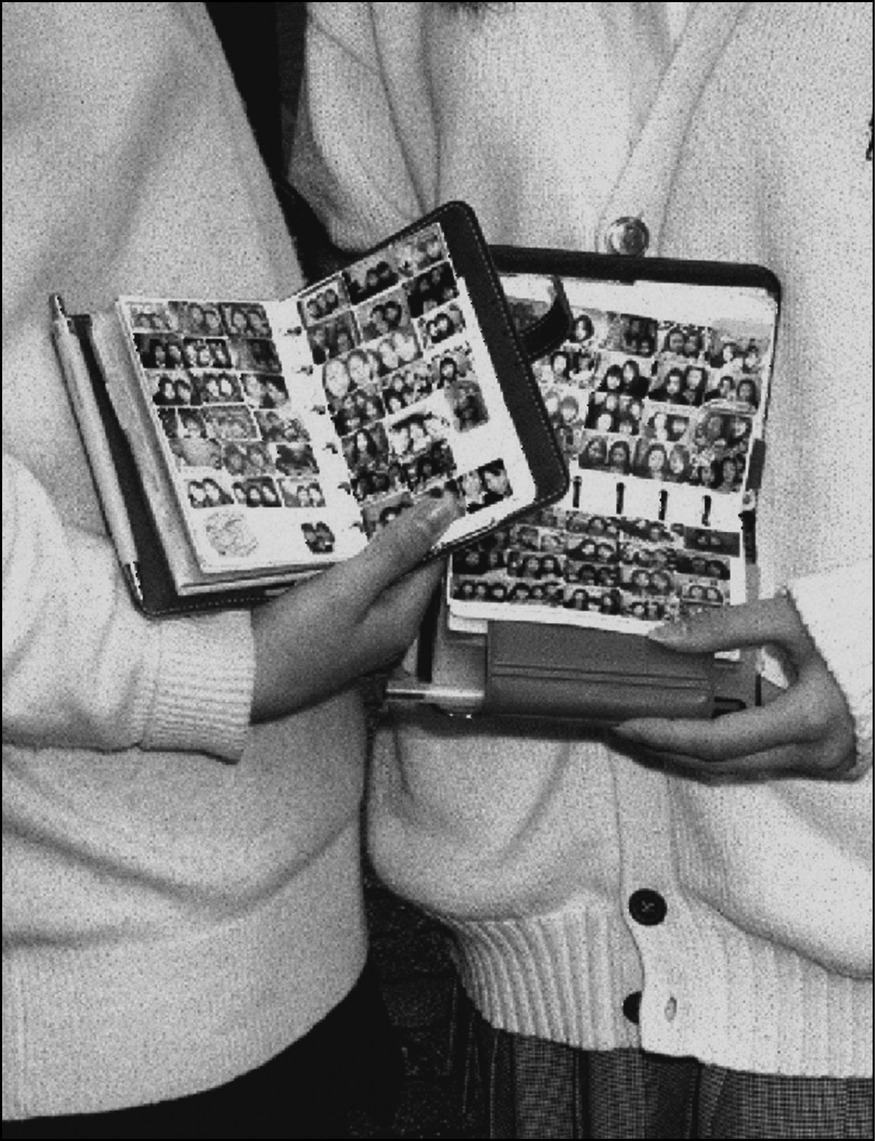

hit the streets, one of her first suggestions had been taking the Tamagotchi off the watchband and putting it on a keychain. The reasoning was twofold. First of all, kogals loved to attach keychains and other tchotchkes to their handbags. But an even bigger consideration was that a girl might or might not carry a wristwatch, but she wouldn’t be caught dead leaving home without her “pocket bell”—Japanese for pocket pager. Making the Tamagotchi a handheld object rather than a watch would more closely align it with this indispensable accessory.

For those who may not remember, pocket pagers were products of the pre-cellphone era. They were little devices roughly half again as large as a matchbox and maybe twice as thick, with a tiny black-and-white LCD display along one edge. Originally intended as a way for doctors and businessmen to stay in contact with their offices in an era before cellphones, their only function was displaying the numbers of people who’d called you. Every pager came with its own telephone number, which you’d give out to anyone with whom you wanted to keep in touch. If they needed to reach you when you were out, they would instead call your pager, which would in turn prompt them to key in a callback number. Your pager would then display that number and beep to alert you. (Thus their nickname, “beepers.”) In 1993, when prices for a monthly subscription dropped to roughly three thousand yen (around thirty U.S. dollars), suddenly teens could afford them. They spread through this new demographic like wildfire, to the point that a prime-time drama called Why Won’t My Pager Beep? emerged as one of the year’s most popular shows.

Pagers were a big thing among American youth in the early nineties, too. The difference was the demographic. In the States, they weren’t associated with schoolkids. They were associated with drug dealers, pimps, and rappers. But even they used them like any respectable doctor or lawyer would: for receiving phone calls. It was in Japan that some unsung outside-the-box thinker repurposed them as makeshift proto-texting devices. We’ll never know who dreamed up this particular life hack, but chances are it was a schoolgirl, for they were the true power users of this new lexicon.

They were aided in their endeavors by a peculiarity of the Japanese language that allows numbers to be read phonetically. This allowed you to type in strings of numbers that could be read as words, if the person you were paging knew that was what you were up to. Instead of a callback number, you’d instead enter 3341 (sa-mi-shi-i)—“I’m lonely.” To which your recipient might reply, 1052167 (do-ko-ni-i-ru-no)—“Where are you?” Your answer, 428 = “Shi-bu-ya.” It was kludgy and indirect; in the earliest iterations of the technology, the numeric code would take the place of the callback number, so it was necessary to discuss things ahead of time for a recipient to know who was messaging. Still, the hugely popular practice represented an early form of mobile texting, and Japanese schoolgirls were the first people on the planet to incorporate this now-common habit into their daily lives.

They texted so furiously, in fact, that schoolgirl users quickly began outnumbering the salarymen users. This sparked a peculiarly localized mid-nineties Japanese telecom tech race to rush out new products designed specifically for girls. Season after season, makers debuted new sets of features for an increasingly tech-savvy and discriminating crew. The ability to display alphabetical and Japanese scripts; then kanji characters; and later, rudimentary graphics in the form of hearts and smiley faces, the ancestors of modern-day emoji—all these functions were incorporated into pagers specifically to appeal to Japanese schoolgirls. By the peak of the phenomenon, in 1996, ten million beepers were circulating on Japanese streets. The majority of them were being used by women, and the majority of the women were under twenty years old. In their life-hacking of devices not originally intended for them, schoolgirls transformed from consumers into innovators. In layman’s terms, they were the nation’s power users and tastemakers for mobile technologies, and the entire Japanese tech industry knew it.

In a certain sense, the Tamagotchi can be thought of as a beeper minus the telecommunications technology, packed with an army of super-kawaii mascots instead of telephone numbers.

. The Tamagotchi is more than a hit—it’s a full-blown fad. Bandai can barely keep up with demand; shortages are constant, as are the lines that form outside every toy store that gets even a handful of the gadgets in stock. At the toy shop Kiddyland, located in the fashion district, the lines sometimes stretch all the way up Omotesando to Harajuku Station, five blocks away.

Emma Miyazawa is eight years old. Like most little girls her age, she desperately wants a Tamagotchi of her own. She can’t get her hands on one, because they’re sold out nearly everywhere. But Emma has a trick up her sleeve. Her grandfather is Kiichi Miyazawa, the former prime minister of Japan.

Emma’s birthday is coming up. She tells Grandpa that what she’d really like is a Tamagotchi. Kiichi has lots of time on his hands now that he’s retired. Would she like him to take her to the toy store? She would. And so it was that a limo bearing Emma, Grandpa, and an armed member of the Japanese secret service pulled up to the curb outside of the Harajuku Kiddyland on a winter afternoon.

Kiichi, once the most powerful man in Japan, surveyed this corner of his former domain. The line was already hundreds long by this point, with a knot dozens deep clustered around the entrance. Things didn’t look good. But Kiichi had seen and survived worse. George Bush the elder had vomited in his lap during an official dinner. Compared to that, this scrum was nothing.

Taking Emma by the hand, Kiichi strode purposefully to Kiddyland’s door. Years later, Emma recalled hearing the family name burbling throughout the crowd, and the people parting “like the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments.” It was the first time that she realized just how different her grandfather was from other men.

Presently the trio reached the head of the line. Mustering the gravitas only a former head of state can bring to bear, Kiichi addressed the clerk who stood guard over the latest jewels of Japan’s pop-cultural kingdom.

“One Tamagotchi, please.”

The Kiddyland employee looked at the former prime minister for a moment, then the queue of eager citizens stretching far behind him.

“Sir, I’m afraid I’m going to have to ask you to get in line.” No exceptions, not even for a former prime minister. Such was the demand for the Tamagotchi at the peak of the craze.

After the little digital eggs spread through Japanese society at large, they leapt the nation’s borders to colonize North America and Europe. Within two years of its debut, forty million Tamagotchis would be living, eating, and soiling screens around the globe, earning its co-creators the 1997 Ig Nobel Prize in Economics (“for diverting millions of man-hours of work into the husbandry of virtual pets.”) The series is still going strong, in fact. As of its twentieth anniversary in 2017, the current number in circulation is double that. One of the reasons for its longevity, fittingly, is evolution. In a great circle of kawaii culture, some of the latest iterations actually incorporate Sanrio characters into the action, letting players create supercute fusions of traditional Tamagotchis and Hello Kitty—though, predictably if a little disappointingly, with functionality limited so as to avoid untoward situations. A traditional Tamagotchi might poop or pass away, but the question as to whether Kitty has a functioning digestive tract or an afterlife will remain a mystery for the time being.

unlike so many other cultural exports ranging from food to comic books, failed to find much of a foothold in the West. Chances are you’ve never heard of Kahara, or even more successful kogal favorites like Namie Amuro, Ayumi Hamasaki, or Hikaru Utada. The cynical sort might say it is because they are products of a system designed to reward mediocrity, but there is no actual shortage of musical talent in Japan. Idols rule because mainstream Japanese pop is the product of a database that emphasizes pleasure and escape over virtuosity and artisanship. (“You don’t need to practice singing and dancing,” the former AKB48 idol Rino Sashihara told a group of schoolchildren on the long-running variety show Waratte Iitomo in 2013. “Most idol fans are old men, these days, and they think girls who can’t dance are cuter.”)

In virtually every other way, however, schoolgirl tastes wormed their way into the fabric of daily life all over the world. The Tamagotchi, silly though it may be, encapsulates how much we take for granted, as our always-connected, digitally enhanced daily lifestyles emerged. These schoolgirls were the first to collapse a gadget’s value into a single criterion: How does this connect me with others? It was the first appearance of schoolgirl tastes on the global scene, the first export of Japan’s kawaii culture in a non-Kitty context. It also heralded a profound shift in the way trends spread around the globe.

This peculiarity of the Japanese marketplace could throw even the savviest foreign companies for a loop. When Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, it proved an instant hit across the globe, with one glaring exception: Japan. There and there alone it flopped, because Apple had neglected to include emoji.

Although “emoji” is usually and quite naturally pronounced in America like “email” or “emotion,” which it resembles in English, the word is actually a combination of two Japanese words: e (pronounced “eh”), meaning picture, and moji, meaning letter or character. A better translation might be “pictogram.” But, like those for other uniquely Japanese inventions—samurai, sushi, haiku, kaiju—the loanword has stuck.

The little glyphs debuted on Japanese mobile phones in the late nineties, a natural fusion of texting and kawaii illustration culture. As young women eagerly peppered their missives with little hearts, smiles, and weeping faces, they elevated the emoji from a form of visual punctuation into a new grammar for online communication. By the early twenty-first century, emoji were no longer an optional feature for the female cellphone users of Japan; they were critically necessary for text communications. Yet cellular texting and data services of the day weren’t designed for compatibility among competitors’ platforms. Rival companies had no incentive to cooperate or standardize, so every company coded its emoji somewhat differently; one carrier’s smiley might well be another’s frown. Thus, when it came to picking a cellphone, boyfriends and husbands tended to follow the lead of the ladies in their lives. If a phone didn’t take off with female customers in Japan, it didn’t take off, period. Apple’s belated realization of the emoji’s importance launched a complicated, multiyear cooperative effort with Google to standardize the little icons for international use. The debut of emoji on the iPhone virtual keyboard in 2011 transformed the rest of humanity into Japanese schoolgirl-style texters.

At the turn of the millennium, the cultural epicenters of Hollywood, New York, London, and Paris still reigned as the world’s trend factories. But trends like texting with emoji and products like the Tamagotchi represented new eddies in the flow of pop culture globally. Things that Japan’s youth found interesting were increasingly things that young people all over the world found interesting. And while the Tamagotchi fad faded, it paved the way for an even more popular wave of digital and pocket-sized monsters. That egg-shaped gadget designed for schoolgirls was but a taste; its successors would decisively Japanize the global imagination. The story of how that happened involves a little detour into a far less fashionable part of the city, filled with a far less fashionable crowd of people.