OPPOSING ARMIES

THE GERMAN 7. ARMEE

The Germany Army did not anticipate the scale of losses suffered in the West in June 1944, and so replacements fell far short of needs. The army high command had anticipated 90,000 casualties on all fronts in June 1944, but in fact suffered over 165,000. The units in the west under OKW command estimated their June losses as 69,628, with 35,454 in France and the remainder in Italy and the Balkans. However, these estimates proved too low as losses in the Cherbourg campaign alone were about 55,000 men including Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe, and the overall total in the West more than 83,000.

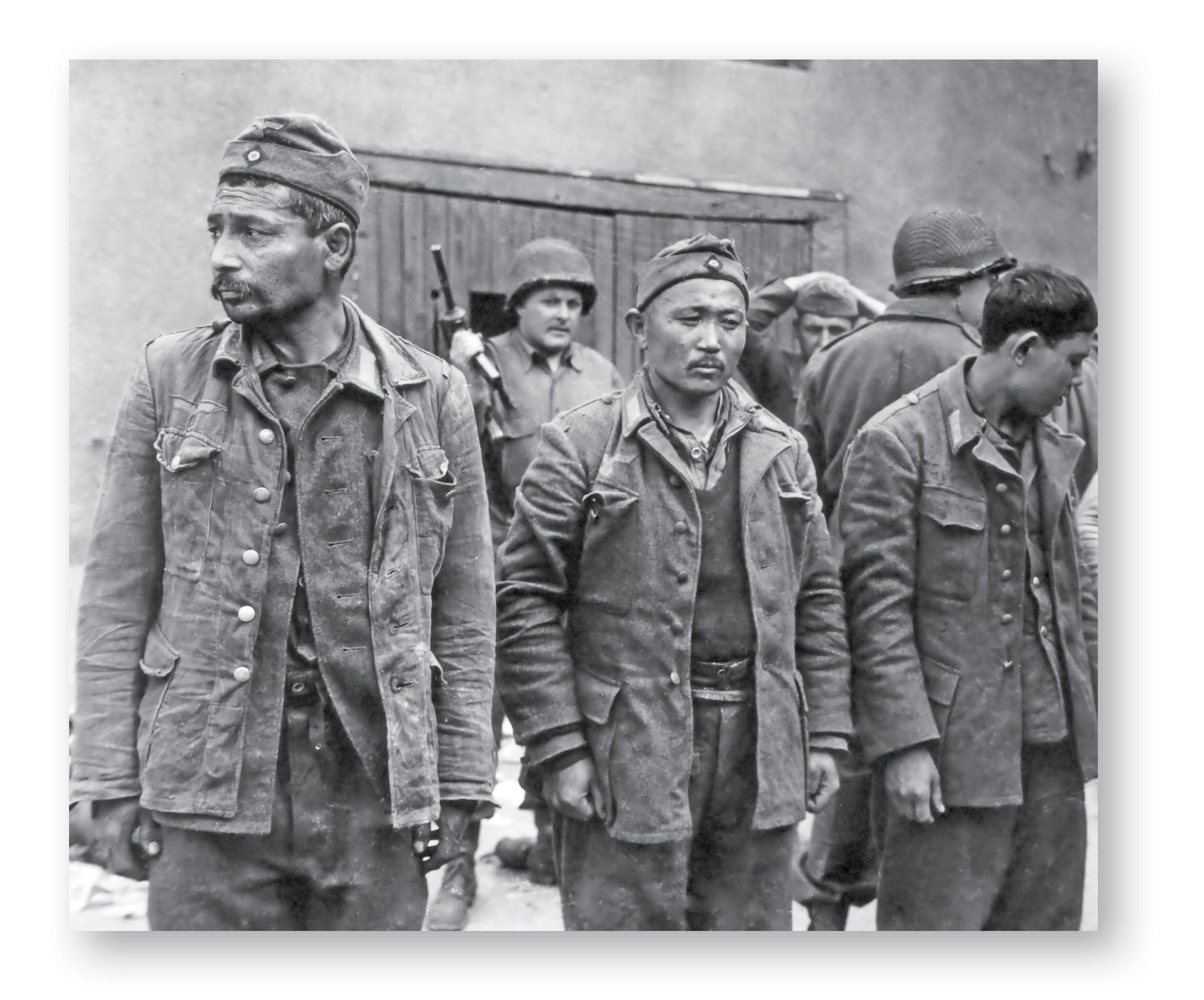

Manpower shortages in the Wehrmacht in Normandy led to desperate measures including the use of several Ost-Bataillon in Kampfgruppe König on the approaches to La Haye-du-Puits. These were made up of former Soviet soldiers who volunteered for the Wehrmacht to escape confinement in Germany’s lethal prisoner-of-war stockades. The Eastern battalions in Normandy included Soviet troops from the far-flung republics including Volga Tartars and Georgians. These prisoners were photographed in a holding area near Bréhel in early August 1944.

OKW was allotted only 34,500 replacements for these losses which had to be shared between OB West and the Italian Theater. By mid-July, OB West had been allotted 12,000 replacements of which only half had arrived. Total OB West casualties between D-Day and July 15 was about 100,000 men, roughly equivalent to all the infantrymen on the front lines on July 1. The dynamics of battlefield attrition were running strongly against the German defenders in Normandy. By early July, Heeresgruppe B recommended a switch to the “pipe-line” style of replacements used by the US Army, but it was too late to implement such a change. The unanticipated scale of casualties convinced Rundstedt that instead of three replacement battalions per division per month, at least ten per month were needed, nearly equivalent to the entire division’s combat strength.

By the end of June 1944, OB West’s logistics network was near to failure. Allied air strikes had caused the loss of the 10,050 tons of munitions, 1.6 million gallons (6.2 million liters) of fuel and lubricants, and trucks with the capacity for hauling 3,400 tons. By the end of June, units in OB West were suffering from a daily deficit of 220,000 gallons (833,000 liters) of fuel. The units had a daily requirement of 14,000 tons of truck capacity but had only about 5,000 tons. The French railway network was on the verge of collapse and on June 24–25, Allied air attacks shut down the last rail lines between France and Germany. By the end of the month, OB West could only transport about 400 tons out of the daily minimum requirements for 2,250 tons of supplies (1,000 tons of munitions; 1,000 tons of fuel; 250 tons of rations).

The tank element of the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division, SS-Panzer.Abt. 17, was equipped with 42 StuG IV assault guns as an expedient due to a shortage of normal tanks. It was similar to the more common StuG III, but based on the PzKpfw IV chassis. The battalion had been reduced to 11 operational StuG IVs when the US offensive resumed on July 3, 1944. This one was lost in the days preceding the start of Operation Cobra.

Due to manpower sustainment problems in 1944, the German Army began to adopt different reporting practices regarding divisional strength and this became formal practice in April 1944. The previous practice of reporting overall strength (Istbestand) could be deceptive after divisions had suffered heavy casualties. For example, a division reporting a strength of 4,000 men might seem capable of combat but, in fact, the 4,000 men could be 3,800 men in non-combat roles such as administration and supply and only 200 men fit for combat duty. The most essential evaluation of the division, the “combat strength,” only counted those troops actually involved in direct combat and they represented about 40–50 percent of overall strength in a full-strength unit. Since units in combat frequently did not have precise counts of troops, infantry divisions would report on their combat battalions in five states: strong (over 400 combat effectives); medium strong (over 300); average (over 200); weak (over 100); and exhausted (under 100 men). Likewise, corps reports to the field army headquarters were abbreviated to four levels of combat value for its divisions: (Kampfwert) 1 (suitable for offensive action); 2 (limited suitability for offensive action); 3 (suitable for defense); and 4 (limited suitability for defense).

Due to Hitler’s perceptions of the Allied threat, Panzergruppe West contained the bulk of German forces in Normandy, and especially the more valuable units, with four corps in Normandy compared to two corps in the 7. Armee’s Normandy sector. Apart from the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division, all the Panzer and Panzergrenadier divisions in June 1944 were in the British sector, as well as all three of the heavy Nebelwerfer rocket artillery brigades.

In general, the 7. Armee was very weak in armor support, limited to divisional Panzerjäger companies and a few corps-level assault gun battalions. This was not widely regarded as a problem, since the local commanders did not feel that the hedgerow terrain was at all conducive to tank or assault gun use. In fact, local German commanders were surprised at how extensively the Americans used armor, and how effective it was in certain circumstances.

The field artillery of 7. Armee was outgunned in terms of the quantity and quality of cannon. During the first week of July 1944, 7. Armee had about 350 guns and howitzers in its field artillery battalions compared to about 1,200 in the First US Army. Aside from the disparity in numbers, the German arsenal was an incredibly motley selection numbering 19 different types of which only half, about 190 guns, were the standard 105mm lFH 18/40 and 150mm sFH 18 divisional guns. The rest were expedient types including over 110 war-booty Soviet, French, and Italian guns. II Fallschirmjäger Korps was particularly weak in artillery and at the beginning of July three field artillery battalions were in the process of being transferred from the 19. Armee in southern France, equipped with war-booty Italian 149mm sFH 404(i) guns.

The most advanced small arm to see use in the hedgerow fighting was the FG 42 automatic rifle. This was a Luftwaffe weapon developed after the Crete airborne operation to provide the Fallschirmjäger with a compact weapon with high firepower. Although a popular and successful weapon, it was complicated and expensive to manufacture. This is an example captured during the St Lô fighting from II FS-Korps troops.

Ammunition supplies were not as lavish as in the First US Army. The ammunition issue (Munitions-ausstattung) for the standard 105mm lFH 18/40 was 125 rounds, based on expected expenditure in one day of heavy combat, and the division nominally had three issues per gun. At the start of the American offensive on July 3, 84. Korps had only about 180 rounds per 105mm howitzer, half a standard issue, while II Fallschirmjäger Korps had about 330 rounds per gun (88 percent); there was a re-supply of a further 560 rounds per gun in army-level depots. Overall, ammunition supplies had fallen from D-Day when there were about eight days of ammunition for the 105mm lFH 18, to less than three days’ supply at the beginning of July 1944. It was somewhat better in the medium battalions, with levels having fallen from about seven days’ supply on D-Day to about five in early July. Had the 7. Armee been able to use all their stockpiles in the July fighting, the exchange ratio against the US Army would not have been so bad and roughly on the order of 4:7 in favor of the Americans. Most of the OB West ammunition dumps were well behind the lines and subject to direct Allied air attack, and the truck and rail transport to the front was vulnerable to Allied air interdiction. The ammunition supply issue was further complicated by the need to supply some 11 different types of ammunition for the 19 different types of field guns and howitzers.

Although detailed artillery ammunition expenditure data for the 7. Armee sector is lacking, German artillery officers estimated that during July 1–10 fighting around Caen, Panzergruppe West had an artillery fire-exchange rate of 1:7.7 with the British/Canadian forces. The fire-exchange rate in the 7. Armee St Lô sector was no better since the Panzergruppe West sector was favored for heavy artillery. The 7. Armee estimated that in the week after the renewed American July 3 offensive, that First US Army was firing five to ten times as many rounds per day. Further examples are found in divisional records. On July 13, 1944, the 352. Infanterie-Division fired 2,200 rounds compared to 12,000 rounds from the attacking US 35th Infantry Division. During the final two days of fighting around St Lô on July 17–18, the 352. Infanterie-Division fired 1,800 rounds versus 32,000 rounds from the US side. The imbalance late in the campaign was due to both a shortage of ammunition and a loss of cannons to American counter-battery fire. A First US Army report provided a critical assessment of the shortcomings of German field artillery in the Normandy fighting:

The enemy did not employ his artillery to the full extent of its known capabilities. Hampered by very poor ground observation and no air observation or recent photo cover, the enemy largely fired map-data corrected on terrain features, road junctions, and bridges. This type of firing was sporadic and usually of a few rounds only. Although three observation units were located, their work could only be rated as mediocre. Counter-battery firing as well as the massing of fires were both the exception rather than the rule. There was no Corps artillery organization, with the limited available corps artillery usually either being attached to divisions without organic artillery or assigned a reinforcing role.

By July 1944, the German ground forces had given up any hope of air support from the Luftwaffe, and it was available only on a very limited basis. Fighter strength was being husbanded for strategic defense of the Reich, and bomber missions were mainly assigned to anti-ship operations against the Allied amphibious and transport fleet.

Mortars were one of the most lethal infantry weapons in the bocage fighting. This is a German 81mm Granatwerfer 34.

At the beginning of July 1944, 7. Armee had a combat strength of about 35,000 troops. 84 AK at the base of the Cotentin peninsula and on the east side of the Vire River contained the bulk of the 7. Armee units. The most critical sector at the base of the Cotentin was the western region bounded by the sea and the Gorges marshes. The US Army could have turned the flank of 84 AK in this sector in mid-June, but did not do so since the focus was on the capture of Cherbourg to the north. Hitler insisted that a defense line be established to block any future attempts. The initial outpost line was held by Kampfgruppe König, commanded by Eugen König who had led the 91. Luftlande-Division behind Utah Beach. All that was left of his division at the start of July was about 400 combat effectives. Kampfgruppe König incorporated the left-overs from the units that had fought at the base of the Cotentin peninsula earlier in June during the Cherbourg campaign, including 2,600 men from the shattered 243. and 245. Infanterie-Divisions, plus 800 Osttruppen, former Red Army prisoners of war who volunteered to serve in the German Army. Since this formation stood in the way of the initial US offensive on July 3, it is worth describing in more detail.

The backbone of the German field artillery was the 105mm leichte Feld Haubitze 18, with three battalions in each infantry division. There were 129 of these in 7. Armee service in mid-July 1944, including some of the improved lFH 18/40 versions with the lightweight carriage.

The Kampfgruppe consisted of smaller formations, usually called Untergruppen, based around their previous formations. The chart below lists the sub-formations from west to east. Choltitz ordered the Volga-Tatar battalion withdrawn after one of its soldiers tried to shoot its German commander, but Simon’s Untergruppe was so short of troops that the sullen ex-Red Army troops were left in place. Ost-Bataillon 635 under Oberst Bunjatchenko was also assigned to Kampfgruppe König, arriving shortly after the renewed American offensive on July 3. Even though König’s force was short of infantry troops, a substantial amount of artillery remained from the original divisional formations. Armored support, aside from that of division Panzerjäger companies, included StuG.Abt. 902 with 30 StuG III assault guns and a few war-booty French light tanks from Panzer-Abteilung 100.

|

Kampfgruppe König, July 3, 1944 |

|||

|

Untergruppe |

Source |

Combat Strength |

Strength (battalions) |

|

Eitner |

265. Inf.Div. |

1,000 |

2 |

|

Lewandowski |

91. LL.Div. |

400 |

2 |

|

Jäger |

KG 265. Inf. Div. + Ost-Bataillon Huber |

400+200 |

2 |

|

Simon |

243. Inf. Div. + Tatar-Bataillon 627 |

1,200+600 |

3 |

|

Support weapons, Kampfgruppe König, July 3, 1944 |

|

|

75mm infantry gun |

12 |

|

75mm PaK 40 AT gun |

12 |

|

Soviet 76mm guns |

34 |

|

88mm AT guns |

6 |

|

105mm pack howitzer |

2 |

|

Soviet 122mm guns and howitzers |

14 |

|

150mm infantry howitzers |

2 |

|

French light tanks |

3 |

|

StuG III assault guns |

35 |

|

Marder III tank-destroyers |

9 |

A main line of resistance called the Mahlmann Line was established through the town of La Haye-du-Puits when the 353. Infanterie-Division was first stationed there in late June. It was followed by a secondary line 6 miles (10km) further south called the Water Line (Wasserlinie) that followed the valleys of the Sèves and Ay rivers. Choltitz formed two further defense lines behind these, but they were seldom mentioned in official records because Berlin regarded rear defense lines as a sign of defeatism.

The ammunition supply in German artillery units was complicated by the extensive use of war-booty weapons. This Soviet 122mm A-19 M1931 corps gun was probably from Batterie. 10, Artillerie-Regiment 265 that served with Kampfgruppe König in the fighting around La Haut-du-Puits.

On the east side of the marshland was the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division “Götz von Berlichingen.” This division had seen small-scale combat since D-Day, originally in the Utah Beach area. In spite of its impressive designation, its armored element was made up of only 42 StuG IV assault guns and it had no armored half-tracks. It was motorized rather than mechanized, and it was short of trucks. The divisional reconnaissance battalion had been committed to the fighting near Carentan and bore the brunt of the division’s 790 casualties in June. By the end of June, the division was still near full strength with a combat strength of over 6,000 men. It was reinforced by 1,200 men of the experienced but decimated Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 and a Kampfgruppe from the 275. Infanterie-Division. As a result, it was the strongest single division in the corps at the start of July 1944. It was reinforced by Panzerjäger-Abt. 657 which had 21 towed anti-tank guns in the 50mm–88mm range and five self-propelled Panzerjäger 4.7cm 35R (f).

Dollman had planned to pull this division out of the line at the end of the month to serve as the main 7. Armee reserve, and replace it with the newly arrived 353. Infanterie-Division. This was a full-strength division that had been stationed with the 7. Armee in Brittany and arrived in Normandy during the third week of June 1944. One of its regiments, GR 943, was immediately detached to reinforce the exhausted 352. Infanterie-Division near St Lô, yet the division still had significant strength at the start of July and was still in corps reserve behind the Mahlmann Line. The new 7. Armee commander, Paul Hausser, ordered it to begin moving east and it was still in transit on July 3 when the US offensive resumed. As a result, it was ordered to return to its original defense line to reinforce Kampgruppe König. Parts of the division remained in corps reserve, while bits of the division were fed in as reinforcements through the July 1944 fighting. The other June reinforcement in the 84 AK sector was the 77. Infanterie-Division. This division left a portion of its divisional strength back at its home base in St Malo and its contingent in Normandy had been beaten up in the Cotentin fighting in June and reduced to only about 2,000 combat effectives by the start of July 1944.

In late June 1944, the OKW began shifting the 2. SS-Panzer-Division “Das Reich” into Normandy from its original base in southern France, but not all elements had reached Normandy by the beginning of the month. Some of its units had been harassed by French partisans, leading to the infamous Oradour-sur-Glane massacre. It was kept in OKW reserve until July 2 when portions of the division were committed to reinforce Choltitz’s corps.

One of the more obscure but effective anti-tank weapons used during the bocage fighting was the 88mm Raketenwerfer 43 Puppchen (Little Doll) rocket launcher. This weapon pre-dated the man-portable 88mm Panzerschreck and used a similar projectile, but with greater range. There were 130 of these in service with 7. Armee in 1944. This photograph of a captured example shows the electrically-initiated Panzerschreck round rather than the primer-fired Puppchen projectile.

II Fallschirmjäger-Korps near St Lô was significantly smaller than 84. AK, with only two divisions. In addition, the assigned corps support units, including FS-Artillerie-Rgt. 12 and FS-Flak-Rgt. 12, were not available at the beginning of July. II Fallschirmjäger-Korps had a single assault gun battalion, the Luftwaffe FS-StuG.Abt. 12 with an initial strength of 31 StuG III. The corps contained one of the best units in the American sector, the 3. Fallschirmjäger-Division. This was another 7. Armee asset that had been originally stationed in Brittany and then transferred to the St Lô sector in June. The division had been raised in 1944 and so had no combat experience prior to the Normandy fighting. However, it was based on well-motivated, volunteer troops who were put through strenuous training including jump training. In addition, the German paratrooper formations had an unusually high level of automatic weapons, giving them tactical firepower advantages. On the deficit side, the division had only a single artillery battalion available in late June. Local German commanders considered this division to have the combat value of two regular infantry divisions, and its American opponents agreed. Its main tactical problem was that the lack of sufficient forces in its sector meant that it was overextended and all three regiments were deployed on the main-line-of-resistance (Hauptstellung) instead of the preferred tactic of keeping one regiment back in reserve.

|

7. Armee In Normandy, July 1, 1944 |

||

|

Unit |

Commander |

Combat strength |

|

OKW Reserve |

||

|

2. SS-Panzer-Division |

Gruppenführer Heinz Lammerding |

5,000 |

|

Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 15 |

Oberst Kurt Gröschke |

2,500 |

|

|

||

|

7. Armee |

Gen. der WSS Paul Hausser |

|

|

84. Armee Korps |

Gen. der Inf. Dietrich von Choltitz |

|

|

Kampgruppe König |

Gen.Lt. Eugen König |

3,800 |

|

17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division |

SS-Brigadeführer Otto Baum |

8,600 |

|

353. Infanterie-Division |

Gen.Lt. Erich Müller |

8,000 |

|

77. Infanterie-Division |

Oberst Rudolf Bacherer |

2,000 |

|

|

||

|

II Fallschirmjager-Korps |

Gen. der Flieger Eugen Meindl |

|

|

3. Fallschirmjager-Division |

Gen.Lt. Richard Schimpf |

10,000 |

|

352. Infanterie-Division |

Gen.Lt. Dietrich Kraiss |

6,000 |

The other division in II Fallschirmjäger-Korps was the 352. Infanterie-Division. This unit started the campaign in the Omaha Beach sector and was slightly over-strength on D-Day. However, during the subsequent fighting from June 6 to 24 it suffered casualties of 5,407, in effect its entire combat strength. By July 11, the division had suffered 7,886 casualties. The intention had been to pull it out of the line on June 15 and transfer it to southern France to be rebuilt. This was impossible due to the shortage of infantry divisions in Normandy. Its four replacement battalions, equivalent to only a third of the needed replacements, arrived in Montpelier in early July but were diverted to the defense of southern France. Another scheme to pull the division back into the Netherlands in early July also had to be abandoned due to the lack of a replacement unit. At the beginning of July 1944, the division had been reduced to a combat strength of about 2,000 men, consolidated into one of its three original regiments. To keep it in the line, it was reinforced by battle groups taken from the remnants of other infantry divisions. As a result, at the end of June it had a combat strength of 5,480 men, as detailed below.

|

Unit |

Origins |

Combat strength |

|

KG Goth |

GR 916, 352. ID |

2,000 |

|

KG Kentner |

GR 897, 266. ID |

1,800 |

|

KG Böhm |

GR 943, 353. ID |

980 |

|

Reserve I |

Schnelle-Brigade 30 |

200 |

|

Reserve II |

II./GR 898, 343. ID |

500 |

|

Total |

5,480 |

THE FIRST US ARMY

The workhorse of the US Army field artillery was the 105mm M2A1 howitzer with this one seen in action outside St Lô on July 18, 1944. Each infantry division had three battalions of these with 12 cannon each.

The First US Army in Normandy had four corps with 13 to 14 divisions facing two German corps with seven to eight divisions. Bradley’s force was a bit large for an American field army since some of its elements were earmarked for Patton’s forthcoming Third US Army.

The US infantry divisions in Normandy were uniform in composition and strength, but significantly different in combat experience and effectiveness. Several of the divisions had only recently taken part in the VII Corps offensive against Cherbourg. These four divisions (4, 9, 79, and 90) had suffered cumulative casualties of 12,665 in June, or an average of 3,165. They had been filled out with green replacements prior to the St Lô offensive. Divisions in the other corps varied in experience level with some divisions such as the 1st and 29th having fought since D-Day, while others were newly arrived and had not seen combat at the beginning of July. Although the divisions were usually well trained, fresh divisions thrown into the bocage fighting usually took days or weeks to become acclimatized to combat. In the case of the 30th Division, it was first put into the line in June in a quiet sector, and so gradually built up combat confidence before being thrown into the maelstrom of the bocage. Other units, such as the 83rd Division, were thrown into combat with no preparation, with predictable results.

|

Unit |

Commander |

|

First US Army |

General Omar N. Bradley |

|

VIII Corps |

Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton |

|

8th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Donald A. Stroh |

|

79th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche |

|

83rd Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon |

|

90th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum |

|

|

|

|

VII Corps |

Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins |

|

4th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton |

|

9th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy |

|

|

|

|

XIX Corps |

Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett |

|

29th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Charles Gebhardt |

|

30th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs |

|

35th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Paul W. Baade |

|

3rd Armored Division |

Maj. Gen. Leroy H. Watson |

|

|

|

|

V Corps |

Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow |

|

1st Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner |

|

2nd Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson |

|

5th Infantry Division |

Maj. Gen. Stafford L. Irwin |

|

2nd Armored Division |

Maj. Gen. Edward H. Brooks |

Two armored divisions had arrived in Normandy by the beginning of July. The 2nd Armored Division was an experienced unit, having taken part in the Operation Torch landings in North Africa in November 1942, and having seen combat on Sicily in July 1943. The 3rd Armored Division was new to combat. US doctrine expected to use armored divisions for the exploitation mission once the infantry had broken through the enemy defenses. As a result, both armored divisions were being held back for an eventual offensive beyond the hedgerow country. Nevertheless, there were occasional uses of forces from these divisions during the St Lô campaign. The failure of Task Force Y of the 3rd Armored Division at Villiers Fossard on June 29–30 served to reaffirm the prudence of letting the infantry divisions conduct the breakthrough mission.

Through 1943, the US Army had overlooked the need for separate tank battalions to support the infantry divisions in their missions. This had become apparent during the Tunisian campaign in early 1943, leading to initial efforts to develop better combined-arms tank-infantry tactics. The September 1943 re-organization of the armored divisions freed up about 40 tank battalions and these provided almost enough to attach one tank battalion per infantry division in France in 1944. By mid-July 1944, the First US Army had a total of 11 separate tank battalions.

The US Army had established armored group headquarters to coordinate tank battalions at corps level rather than directly attaching them to divisions. This practice was still in place at the start of the Normandy campaign, but gradually gave way to a practice of semi-permanently attaching specific battalions to specific divisions once the advantages of having familiar units fighting alongside one another became clear. Due to the late change in US Army tank-infantry policy, its doctrine, training, and technology for tank-infantry cooperation were all a bit rough. The first field manual for tank infantry cooperation was not released until March 1944 and most divisions had little or no practical tank-infantry training prior to arriving in France. Neither the M4 medium tank nor the M5A1 light tank were well suited to the infantry support role, lacking the armor needed to resist typical German anti-tank weapons such as the 75mm PaK 40 anti-tank gun or Panzerschreck anti-tank rocket launcher. Although steps were underway to improve tank-infantry communication, the infantry platoon’s SCR-536 “handie-talkie” was an AM transceiver that could not interact with the tank’s FM radios; the company’s SCR-300 “walkie-talkie” radio was FM, but operated on a different band to the tank radios. The shortcomings in doctrine, training, and technology were worked out during the course of the bocage fighting.

The heavy firepower of the divisional artillery was the 155mm M1 howitzer, with each infantry division having one battalion with 12 cannon. This is the 127th Field Artillery Battalion of the 35th Division in action north of St Lô on July 16, 1944.

By mid-July 1944, First US Army had a total of 18 tank destroyer battalions of which 11 were equipped with the M10 self-propelled 3in. GMC and seven with the towed 3in. gun. Due to the lack of German armored vehicles in the bocage country, these battalions were used in other roles. The towed 3in. guns were unpopular in Normandy since they were too large and heavy to deploy in the bocage. More often, they were seconded to divisional artillery in an indirect fire role. The M10 3in. tank destroyers proved more useful and were generally deployed with the infantry divisions to provide mobile fire support as surrogate tanks.

The one area of unquestioned US Army superiority in Normandy was in field artillery. Artillery was the primary killing arm on the World War II battlefield, accounting for the majority of enemy casualties. US and German artillery composition at divisional level was similar on paper, with the US infantry divisions having three 105mm howitzer battalions and one 155mm howitzer battalion. However, US units had their full equipment sets while German divisions in Normandy often had substitutes, such as war-booty weapons. US divisional artillery was more mobile than its German equivalent since it was fully motorized rather than horse drawn. In addition, it had a modern fire direction center networked downward to the infantry regiments and upward to corps artillery. Another important advantage was the addition of a pair of light aircraft for forward observation in each artillery battalion.

Aside from the field artillery advantages at divisional level, the First US Army enjoyed significant advantages at corps and field army level. Each corps generally had one or more field artillery groups, a headquarters controlling two to four field artillery battalions usually with 155mm howitzers or heavier weapons. The First US Army was supported by the 32nd Field Artillery Brigade, a special long-range formation which during this campaign usually had three 155mm gun and three 240mm howitzer battalions. These were used for interdiction and counter-battery missions. By the middle of July 1944, the First US Army and its subordinate corps had 51 non-divisional field artillery battalions including four 105mm towed howitzer, four 105mm self-propelled howitzer, three 4.5in. gun, 16 155mm howitzer, 11 155mm towed gun, four 155mm self-propelled gun, four 8in. howitzer, two 8in. gun and three 240mm howitzer battalions.

General Raymond Barton, commander of the 4th Infantry Division, bluntly described the importance of the field artillery during the Normandy fighting:

The artillery was my strongest tool. Often it was my only reserve. My basic principle of artillery employment was to try to position it so that I could maneuver its fire in lieu of a maneuverable reserve. I repeatedly said that it was more a matter of the infantry supporting the artillery than the artillery supporting the infantry. This was an overstatement, but not too much of one. The basic evidence of that fact is that our doughboys never wanted to attack unless we could put a Cub (L-4) airplane in the air. I wish I knew the countless times that positions were taken or held due solely to TOT’s. I also wish I knew the innumerable times, in some of which I personally participated, when [German] counterattacks were smeared by the artillery. And they were counterattacks that would have set us on our heels had it not been for the artillery.

TOT’s were the acronym for “Time-on-target,” also nicknamed “serenades.” Field artillery is most lethal against infantry when the first rounds strike, and the number of casualties quickly diminish once the enemy escapes into fox-holes. Serenades were intended to increase the lethality of fire strikes by landing the first barrage on the enemy position simultaneously rather than in an erratic succession. The use of fire direction centers permitted US field artillery to conduct serenades at battalion, division or corps levels, massing multiple batteries or battalions.

Artillery ammunition stockpiles in the First US Army had not reached the desired levels by the beginning of July due to the Channel storm in late June that wrecked the artificial harbor at Omaha Beach. As a result, restrictions were applied for the July offensive with a corps-wide restriction to one unit-of-fire on the day of initial attack, half a unit-of-fire for a subsequent attack and a third of a unit-of-fire on normal days. A unit-of-fire was the number of rounds of ammunition expected to be fired in a day of heavy combat. This varied by weapon; for example, it amounted to 120 rounds for the 105mm towed howitzer or 1,440 rounds per 105mm howitzer battalion. Even if artillery loads were below the usual standards, they were quite lavish compared to German supplies. During the two weeks of fighting up to the capture of St Lô, First US Army artillery use averaged half a unit-of-fire per day, as detailed in the chart below.

For the German infantry in Normandy, the most hated and feared aircraft was the diminutive L-4H, a militarized version of the popular Piper Cub. These were used by the forward artillery observers of US Army field artillery battalions and their presence over German lines was usually followed by an artillery barrage. This particular aircraft was flown by 1Lt. John Donnelay of the V Corps artillery squadron.