| 5 | Hitler’s War |

Czech border, 4 October 1938: in accordance with the Munich agreement, Wehrmacht forces, including Claus von Stauffenberg’s 1st Light Infantry Division, moved into the Sudetenland. The army shared the general sense of relief that the crisis had been resolved without war, the division’s war diary remarking: ‘The tension of the last few days is easing.’ The German-populated towns, such as Mies, greeted the German occupiers with ‘indescribable jubilation and a shower of flowers’. In stark contrast, places with a predominantly Czech population, such as Nurschan near Pilsen reacted with undisguised hostility. Stauffenberg himself, as the division’s senior logistics officer, was concerned with organising the feeding of his own troops and that of the civilian population: the first real test of his organisational abilities outside the make-believe world of military manoeuvres. His ability earned him a special mention in his commander’s report when the division withdrew to Germany on 16 October. Meanwhile, on 21 October, Hitler, angry at being deprived of his full prey, issued secret orders to the Wehrmacht to prepare for the occupation of the rump of Czechoslovakia the following spring. On returning to Berlin from Munich he had complained to Schacht: ‘That fellow Chamberlain has spoiled my entry into Prague.’ He would not be thwarted next time.

Countess Nina von Stauffenberg and her three young sons Berthold, Heimaren and Franz Ludwig, took up residence in Wuppertal, in December 1938 to be close to her husband, whose divisional base was located in the un-lovely north-western city. The Stauffenbergs were near neighbours of the family of the division’s adjutant, Captain Henning von Blomberg, son of the fallen war minister, and destined to die in North Africa in 1943, making way for Stauffenberg’s near-fatal Tunisian assignment. For now, however, as the final months of European peace ebbed away, the Stauffenberg children played happily with the young Blombergs.

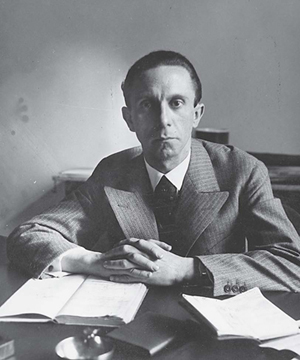

Dr Joseph Goebbels at his desk in the Propaganda Ministry, where he organised the counter-coup on 20 July 1944.

Germany, 9 November 1938: a fateful date in German history. Squads of SA Brownshirts and crowds of ordinary Germans, egged on by a propaganda barrage created by Dr Goebbels, mounted a nationwide pogrom against Germany’s remaining Jews. Dubbed the Kristallnacht (‘night of broken glass’) from the number of plate-glass windows in Jewish-owned stores smashed by the mobs, the mass violence saw scores of synagogues set ablaze in cities and towns across Germany. Tens of thousands of Jewish homes and businesses were wrecked, ninety-one Jews were murdered, hundreds more beaten and humiliated, and 30,000 carted off to concentration camps.

The pogrom was sparked off by the assassination in Paris of a junior German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath, by a young exiled German Jew, Herschel Grynszpan, who was enraged by the persecution of his family in Germany. It was a foretaste of the horrors of the Holocaust and revealed openly to the world – for those who had not already noticed – the criminal nature of the Nazi regime. Walking in the wintry woods near Wuppertal in January 1939 Stauffenberg was asked by a friend, Rudolf Fahrner, what the army’s attitude to the pogrom had been. Stauffenberg answered that disgust was so high that there had been talk of mounting a putsch. He added that Beck was the leader of military discontent and that his own commander, Hoepner, was also ‘reliable’; but he cautioned against expecting any major move from the army as a whole. There was little point in expecting firmness, remarked Stauffenberg, referring to the Fritsch and Blomberg debacles, from those who had already had their backbones broken. But a time might come, concluded Stauffenberg, when the army would have to assume its responsibility as the saviour of the nation and the guarantor of Germany’s honour.

A synagogue burns on Kristallnacht, 9 November 1938.

On 15 March 1939, Emil Hacha, the elderly lawyer who had succeeded Edvard Beneš as president of the rump Czechoslovak state after Munich, was summoned to the Berghof and presented with an ultimatum very similar to that which had been issued to Austria’s chancellor, the hapless Kurt von Schuschnigg, on the eve of the Anschluss exactly a year before. Hacha was told that the full force of German military might, including a Luftwaffe air attack on Prague, would be unleashed unless he accepted that his truncated state – already shorn of large tracts of its territory to Hungary and Poland in the wake of Munich – accept German hegemony. The Czech-populated lands of Bohemia and Moravia would be incorporated into the Reich as a German ‘protectorate’ under military control; Slovakia would enjoy a nominal autonomy as a puppet state also under German ‘protection’.

A horrified Hacha suffered a heart attack under Hitler’s bullying onslaught, but after being revived with injections from the Führer’s physician, he signed a document agreeing to the ultimatum, and German forces entered Prague the next day. Czechoslovakia had been wiped from the map of Europe.

On 21 March 1938 German forces also occupied the Lithuanian port of Memel. Ten days later, on 31 March, Chamberlain issued a guarantee to Poland – which was clearly to be Hitler’s next target – that Britain would come to that country’s aid if it was menaced by outside aggression. France gave a similar guarantee. The stage was now set for the Second World War.

As the war clouds gathered in the spring of 1939, with Hitler issuing a directive on 3 April that he intended to invade Poland, the logical end to Germany’s aggressive foreign policy began to dawn on Stauffenberg. Visiting his friend Fahrner in Berlin in May 1939, Stauffenberg exclaimed, ‘This lunatic will make war!’ The following month, another friend, the classicist Karl Partsch, staying with Stauffenberg in Wuppertal, asked him if the time had come to form anti-Nazi cells within the army. Stauffenberg again poured cold water over any hope of expecting real resistance from the army. The officer corps, he said, was only interested in their promotion prospects.

Meanwhile, as the conspirators grasped the unpalatable fact that Hitler did not intend to stop with his Czech territories and was once again gearing Germany up for war, they began to re-tie the threads so brutally severed at Munich the previous autumn. In the summer of 1939, Halder met with Beck in Berlin; and von der Schulenberg and Gisevius travelled to Frankfurt, the location of Erwin von Witzleben’s new command. Carl Goerdeler also called on Witzleben, who was proposing forming a new network of reliable conspirators’ cells throughout the army. The garrulous Goerdeler told Witzleben of his latest plans for enlisting former trade unionist and socialist leaders in the ranks of the opposition – an idea that had already occurred to Stauffenberg, who had told Partsch at their May meeting that workers’ organisations would be a much more reliable seedbed of resistance to Hitlerism than the army.

The Berghof, 22 August 1939: before the plotters’ plans could go any further, however, Hitler summoned his generals to the Berghof for another shock announcement. He was resolved, he said, to settle accounts with Poland. At that very moment, he revealed, Foreign Minister Ribbentrop was in Moscow negotiating a secret accord with the arch-enemy, Stalin’s Russia, so they need fear no intervention from the east. His military audience sat in icy silence before him; Hitler waved aside any objections. The Western powers were worms – he had seen them at Munich – and would not intervene, despite their guarantees to Poland. He had Poland, he concluded, exactly where he wanted it – at his feet. The following day, the bombshell news of the Hitler–Stalin pact between the ideological polar opposites burst on the world. On 31 August Hitler pressed the button for war, ordering the army to invade Poland the following day. Gisevius, meeting Canaris on a back staircase on the Bendlerblock, asked the Abwehr chief what he thought the outcome of the war would be. The little admiral replied with a two-word Latin tag: ‘Finis Germanae’.

Stauffenberg’s 1st Light Division, of which he was by now quartermaster, had been moved up to Konstadt on the Polish frontier under its new commander, General Loeper. Stauffenberg was photographed on 1 September with Loeper and other staff officers, dragging tensely on a cigarette, but looking suntanned and elegant in a forage cap and wearing white laundered shirtsleeves. Later that afternoon, they crossed the frontier, negotiated the rivers Prosna and Warthe. At a crossroads near the town of Wielun on 3 September they heard the news that Britain and France had declared war. As the faces of his men dropped, Stauffenberg made a grim prediction: ‘My friends, if we are to win this war it will depend on our capacity to hold out.’ He forecast that the fighting would last for ten years. By 6 September the division was storming the city of Radom against heavy Polish resistance. The fighting was fierce, Stauffenberg losing his coat and luggage when a staff car was captured by a stray Polish unit left behind by the German advance. He was instrumental in insisting on the court martial of a fellow officer who had had two Polish women shot out of hand for allegedly signalling to Polish artillery. But such upright and chivalrous behaviour was soon to become all too rare in the German officer corps.

On 10 September, during a brief period of rest and repairs to their vehicles, Stauffenberg wrote home that they had ‘won a great battle . . . It could turn into a second Tannenberg.’ By the middle of the month, the Polish campaign was effectively over and only mopping up remained. Stauffenberg found time to give his unflattering views of the Polish peasantry. Displaying a Teutonic arrogance confronting the hereditary enemy, he described them as ‘an unbelievable rabble; very many Jews . . . a people surely only comfortable under the knout. The thousands of prisoners-of-war will be good for our agriculture. In Germany they will surely be useful, industrious, willing and frugal.’

Stauffenberg (smoking) with fellow officers of the First Light Division at the Polish border on the day war began: I September 1939.

Stauffenberg had little idea that the bucolic agriculture-labouring future he envisaged for the Poles and Jews under benevolent German tutelage had little place in the genocidal plans that the Reich’s leadership were already effecting. As the Wehrmacht advanced into Poland their tracks were closely followed by special SS Einsatzgruppen (task forces), squads of hardened killers trained and tasked for mass murder. Answering directly to the SS leader Himmler, their mission was to exterminate Poland’s large Jewish population, as well as the aristocrats, priests and intellectuals who provided the nation’s social, spiritual and political leadership. As the Wehrmacht became aware of the first roundups and mass killings carried out by the Einsatzgruppen, complaints began to surface that the crimes were besmirching the honour of the German army. Several generals – Blaskowitz, Ulex and the future field marshal Georg von Kuechler – protested. One, Joachim Lemelsen, went so far as to arrest and court martial a member of Hitler’s own bodyguard unit, the SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, for massacring fifty Jews. All such protests were in vain: Hitler reprimanded Blaskowitz for his ‘childish’ attitude and commented that wars ‘could not be won by Salvation Army methods’. When Blaskowitz persisted with his protest, complaining that ‘Every soldier feels sickened and repulsed by the crimes committed in Poland by agents of the Reich,’ he was summarily sacked. The activities of the SS and police auxiliary units in Poland were, as yet, but a foretaste of the wholesale atrocities that led ineluctably to the Holocaust itself, characterising Nazi actions in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. But, as reports and rumours of what was happening just to the rear of the front lines began to circulate among the officer corps, though many continued to shut their eyes, no one could any longer pretend to be unaware that Hitler’s rule meant a relapse into barbarism.

On 12 September 1939, Hitler confided to his adjutant Rudolf Schmundt – destined to die as a result of injuries inflicted by Stauffenberg’s bomb on 20 July – that he planned to answer the Anglo-French declaration of war with an all-out assault on western Europe just as soon as the Polish campaign was wrapped up. On 15 September, Stauffenberg’s division was pulled out of its rest area and thrown in to join the forces encircling Warsaw. ‘The Poles,’ Stauffenberg admitted admiringly, ‘fighting with the courage of despair . . . got us into some nasty spots.’ Two days later, on 17 September, hearing that Stalin had carried out his part of his recently agreed accord with the hated Hitler by invading eastern Poland with seven armies, Stauffenberg’s thoughts were with his fellow nobles in the Polish aristocracy:

I do not have the impression that our friends the Bolsheviks are using kid gloves. This war is truly a scourge of God for the entire Polish upper class. They ran from us eastward. We are not letting anyone except ethnic Germans cross the Vistula westward. The Russians will probably make short work of them since . . . the real danger is only in the nationalistic Polish upper class who naturally feel superior to the Russians. Many of them will go to Siberia.

Adolf Hitler with Colonel Rudolf Schmundt and Rear Admiral Karl Jesko von Puttkamer at the Wolfschanze in 1941. Schmundt was destined to be killed by Stauffenberg’s bomb, and Puttkamer to be injured.

Once again, Stauffenberg was still under-estimating the savagery of twentieth-century totalitarianism. In fact, the fate that lay in store for the Polish officer corps at the hands of the Russians was far more terrible even than Siberia: 8,000 of them, along with more than 10,000 civilians arrested later, were murdered in March 1940 in the Katyn Forest on Stalin’s orders, and buried in mass graves. The Germans trumpeted the massacre to a largely disbelieving world in 1943 after discovering the mass graves, which, in their eyes, went some way towards justifying their own acts of barbarous cruelty to Russian prisoners captured on the Eastern Front.

On 27 September 1939, the day that Warsaw finally capitulated, Hitler summoned the commanders of his three armed forces, confided to them his plan to attack in the west, and ordered them to draw up operational details for the assault. To their horror, he insisted that the attack should be carried out as soon as possible, no later than mid-November. The High Command – even pro-Hitler generals like Reichenau – voiced strong objections on both military and political grounds. The troops were exhausted after destroying Poland and needed time to rest, regroup and, not least, absorb the strategic and tactical lessons of the campaign. The winter, they protested, was never a good time to fight a war. Hitler turned a deaf ear to these objections, pointing out that the weather was the same for both sides. Besides, he said, the Allies would not expect an attack and surprise was always a winning factor in war.

In truth, Brauchitsch, Halder and the other generals were hoping that the war could be ended without the need for a further campaign. Although victorious, the Polish campaign had been far from bloodless: Stauffenberg’s division had lost 300 men. They were well aware that an all-out attack on the West would cost even more lives – not to mention the danger that America would be drawn into the conflict if Hitler, as he envisaged, violated the neutrality of Holland and Belgium. They had assumed that by sitting out the winter along the Siegfried Line a window of opportunity could be created for diplomacy to end what they saw as an unnecessary war. Poland, the original casus belli that had brought Britain and France into the struggle, had been comprehensively crushed. The Western Allies had watched passively while this happened without lifting a finger to intervene. It was clear that they were at best half-hearted about continuing the conflict. So why not let sleeping dogs lie? Hitler’s determination to press ahead with an early attack alarmed them; it upset all their calculations and opened the way to a wider war of unknown duration.

In the middle of October Stauffenberg’s division returned to Germany, the campaign complete and Poland subjugated. On 18 October it was re-designated the 6th Panzer Division to reflect the role of the tanks that had been added to its strength since the occupation of Czechoslovakia. Stauffenberg was flushed with victory and took a professional soldier’s pride in his own part in the triumph. His success was reflected on 1 November when he was promoted to the rank of captain and designated a permanent General Staff officer, entitled to wear the coveted broad scarlet stripe along the seams of his trousers. He would not agree with those of his fellow officers and even his own friends and relatives – such as Count Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenberg and his uncle Nikolaus von Üxküll – who maintained that the war was criminal folly and that Hitler must be removed by force. Stauffenberg argued that it was impossible to act against him when the dictator was at such a peak of success.

Stauffenberg as General Staff officer of the 6th Tank Division, Hachenburg 1940.

Stauffenberg also pointed out that Britain and France had declared war against Germany, and that it was a German officer’s duty to defend his homeland. His mind was anyway still on his professional military duties. He had issued on his own initiative a report on the lessons of the Polish campaign based on a questionnaire he had issued to all ranks. He pointed out that it had been the first example of Blitzkrieg in warfare, but that the army’s training, logistics and structure only equipped it to fight an old-style slow-moving war. New warfare, he concluded, would require entirely new methods. He was not to know that it was exactly such methods that Hitler proposed to put into effect in the west within weeks.

The news that Hitler was planning to invade in the west galvanised the dormant conspiracy like a hungry fox entering a hen-coop. At the Abwehr Canaris and Oster held urgent discussions with the group of younger anti-Nazis whom Oster had deliberately recruited with a view to forming an activist nest of effective conspiracy: the lawyer Hans von Dohnanyi; Dohnanyi’s cousin, the brilliant, young, balding and bespectacled theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer; and his boyhood friend Justus Delbrück, along with the aristocratic historian Baron Karl-Ludwig von Guttenberg. Another nest of military conspirators, known as the Action Group Zossen, was based at the large eponymous military base south of Berlin. Further up the military chain of command, Brauchitsch and Halder were as horrified as their juniors. At the Foreign Office, diplomats Ernst von Weizsäcker, Erich Kordt and Hasso von Etzdorf wrote a memo arguing that a war in the west would ultimately mean the end of Germany.

Persuaded by such pressure, the Army Chief of Staff, Halder, encouraged his immediate superior, the more wavering army commander Brauchitsch to refuse outright to carry out Hitler’s plans, and to lend his support to a new putsch if the Führer insisted on going ahead. Halder confided to one of the Abwehr conspirators – Helmuth Groscurth, who would later die of typhus in Russian captivity – that he himself always packed a pistol in his pocket when going to see ‘Emil’, as he derisively dubbed Hitler, but had so far lacked the courage to gun the dictator down.

Assassination was also on the mind of mild-mannered Erich Kordt, who on 1 November during a meeting with Oster at Abwehr headquarters, answered Oster’s complaint that ‘no one could be found who will throw the bomb and liberate our generals from their scruples’ by volunteering for the task himself if Oster would supply the necessary explosives. Oster promised to have a bomb ready by 11 November, the anniversary of the 1918 Armistice, the day on which Hitler had threatened to unleash another war on the West.

The conspirators’ plans now began to move towards the same state of readiness that they had assumed the previous autumn when Munich had pulled the rug from under their putsch. Oster told the indefatigable Gisevius to dust down the old plans for a putsch and to re-activate the old gang of conspirators. Gisevius gleefully recorded in his diary: ‘It’s going ahead: Great activity. One discussion after another. Suddenly it’s just as it was right before Munich in 1938. I rush back and forth between OKW [Army Headquarters], police headquarters, the Interior Ministry. Beck, Goerdeler, Schacht, Helldorf, Nebe and many others.’

Berlin, 5 November 1939: propped up by Halder, Brauchitsch met Hitler in the Reichs Chancellery. Plucking up all his scant reserves of courage, the army chief told the Führer that the attack could not possibly proceed as planned because the Polish campaign had exposed glaring flaws in the army: not merely the technical deficiencies of the kind highlighted by Stauffenberg’s report, but also a fundamental flaw in morale, even instances of cowardice. Instantly, Hitler flew into one of his famous rages, storming at an ashen-faced Brauchitsch and demanding proof of his charges and whether such cowards had been shot. Then he abruptly left the room, leaving the hapless army chief standing helplessly.

As he and Brauchitsch drove back to Zossen – the base where Hitler had darkly hinted that a spirit of resistance to his plans lurked – a shaken Halder, fearing that someone had betrayed their putsch plans, gave orders that all documents relating to the coup should be destroyed. Thoroughly intimidated by Hitler’s outburst of rage, both Brauchitsch and Halder now washed their hands of any plans for a putsch and resigned themselves to the coming war. They were not the only ones to suffer from cold feet.

On 8 November, during a visit to the Western Front to sound out the army commanders Leeb, Bock and Rundstedt, the insouciant Oster produced from his pocket two proclamations written by Beck that were to be broadcast after the military takeover. Leeb’s Chief of Staff, Colonel Vincenz Müller, insisted that he burn them in a large ashtray. As the conspirators’ hopes were literally going up in smoke came shattering news that paralysed any further action in its tracks: a large bomb had exploded in the Munich beer cellar where Hitler had launched his abortive putsch in November 1923. Several people had been killed – but by some malign miracle, the Führer had survived.